Abstract

Background

Knowledge regarding characteristics and transmission of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium and antibiotic resistance in N gonorrhoeae in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, is entirely lacking.

Objectives

To characterise N gonorrhoeae, C trachomatis and M genitalium samples from Guinea-Bissau and to define bacterial populations, possible transmission chains and for N gonorrhoeae spread of antibiotic-resistant isolates.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Two sexual health and family planning clinics, Bissau, Guinea-Bissau.

Participants

Positive samples from 711 women and 27 men.

Material and methods

Positive samples for N gonorrhoeae (n=31), C trachomatis (n=60) and M genitalium (n=30) were examined. The gonococcal isolates were characterised with antibiograms, serovar determination and N gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST). The C trachomatis ompA gene and the M genitalium mgpB gene were sequenced, and phylogenetic analyses were performed.

Results

For N gonorrhoeae, the levels of resistance (intermediate susceptibility) to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, rifampicin, ampicillin, tetracycline, penicillin G and cefuroxime were 10% (0%), 6% (10%), 13% (10%), 68% (0%), 74% (0%), 68% (16%) and 0% (84%), respectively. All isolates were susceptible to cefixime, ceftriaxone, spectinomycin and azithromycin, and the minimum inhibitory concentrations of kanamycin (range: 8–32 mg/l) and gentamicin (range: 0.75–6 mg/l) were low (no resistance breakpoints exist for these antimicrobials). 19 NG-MAST sequence types (STs) (84% novel STs) were identified. Phylogenetic analysis of the C trachomatis ompA gene revealed genovar G as most prevalent (37%), followed by genovar D (19%). 23 mgpB STs were found among the M genitalium isolates, and 67% of isolates had unique STs.

Conclusions

The diversity among the sexually transmitted infection (STI) pathogens may be associated with suboptimal diagnostics, contact tracing, case reporting and epidemiological surveillance. In Guinea-Bissau, additional STI studies are vital to estimate the STI burden and form the basis for a national sexual health strategy for prevention, diagnosis and surveillance of STIs.

Article summary

Article focus

Knowledge regarding characteristics and transmission of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium and antibiotic resistance in N gonorrhoeae in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, is entirely lacking.

We aimed to phenotypically and genetically characterise N gonorrhoeae, and genetically characterise C trachomatis and M genitalium samples from women attending two sexual health clinics in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau and to define the bacterial populations, possible transmission chains and for N gonorrhoeae also to define the presence and spread of antibiotic-resistant isolates from women and additionally a group of symptomatic men.

Key messages

In Guinea-Bissau, N gonorrhoeae isolates displayed high level of resistance to traditional gonorrhoea antimicrobials but have remained susceptible to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, spectinomycin and azithromycin.

Genovar G, D and F were the most prevalent C trachomatis genovars, the usually most common genovar among heterosexuals, that is, genovar E, was rare.

The diversity among the bacterial STI pathogens may be associated with suboptimal diagnostics, contact tracing, case reporting and epidemiological surveillance. Additional studies are vital to estimate the STI burden and form the basis for a national sexual health strategy for prevention, diagnosis and surveillance.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first time N gonorrhoeae, C trachomatis and M genitalium samples from Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, have been phenotypically and genetically characterised to define the bacterial populations, possible transmission chains and antibiotic resistance in N gonorrhoeae.

The study sample was relatively small, and in this setting, it is difficult to perform appropriate sample transportation and storage, as well as optimised diagnostics, which may have resulted in that true-positive samples were lost.

Introduction

Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, is classified as the sixth least developed country in the world.1 The total number of inhabitants is about 1.6 million with 250 000–300 000 living in the capital city Bissau. The healthcare system is exceedingly limited and highly centralised to Bissau.

Guinea-Bissau has previously presented the highest HIV-2 prevalence globally. However, after the civil war in 1998–1999, the HIV-2 prevalence has decreased and in contrast the HIV-1 prevalence has increased.2 HIV seropositive individuals have shown a higher prevalence of bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and presence of several bacterial STIs has been associated with a facilitated HIV acquisition and transmission.2 3

Present knowledge regarding the prevalence of bacterial STIs in Guinea-Bissau is highly limited. Studies from 2001 to 2002 described a prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections of 17% and 4%, respectively, among women with vaginal discharge, and in pregnant women, the prevalence rate for Mycoplasma genitalium was 6.2%.4 5 In a recent study of women attending two sexual health clinics in Bissau, due to urogenital problems, the prevalence of N gonorrhoeae, C trachomatis and M genitalium infections was 1.3%, 12.6% and 7.7%, respectively.2

In Guinea-Bissau, in routine, the laboratory diagnosis of N gonorrhoeae is mainly based on microscopy of Gram stained urogenital smears, no appropriate diagnostics is performed for C trachomatis and M genitalium and no previous study has phenotypically and genetically typed strains of these bacterial STIs. Consequently, knowledge regarding the characteristics and transmission of circulating strains of N gonorrhoeae (including antibiotic resistance), C trachomatis and M genitalium is entirely lacking.

The aims of the present study were to phenotypically and genetically characterise N gonorrhoeae and genetically characterise C trachomatis and M genitalium samples from women attending two sexual health clinics in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau and to define the bacterial populations, possible transmission chains and for N gonorrhoeae to define the presence and spread of antibiotic-resistant isolates from women and additionally a group of symptomatic men.

Materials and methods

Study population

The current study further examined specimens obtained in a previous prevalence study of 711 women attending two sexual health and family planning clinics (Aguibef Clinic and Centro Materno-Infantil Clinic) for urogenital problems in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. All women visiting the clinics from February 2006 to January 2008 were offered participation.2 Sixty samples analysed positive for C trachomatis, 30 analysed positive for M genitalium and four culture-positive N gonorrhoeae isolates were available for further examination. In addition, 27 N gonorrhoeae isolates cultured, during February 2006 to January 2008, from men (n=27) with urogenital symptoms at the National Public Health Laboratory, Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, were included.

Laboratory characterisation

All 31 N gonorrhoeae isolates were initially cultured and preserved at −70°C as previously described.2 6 Briefly, endocervical (women) or urethral (men) samples were cultured within 5 h on modified Thayer–Martin medium for 48–72 h. Species confirmation was based on identification of rapid oxidase production, Gram-negative diplococci in microscopy and use of PhadeBact Monoclonal GC Test (Bactus, Stockholm, Sweden).2 Antibiotic susceptibility testing, serovar determination, DNA isolation and genetic characterisation by means of N gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST) were performed as previously described.7

C trachomatis and M genitalium specimens were initially diagnosed with PCR as previously described.2 Briefly, DNA was isolated from endocervical samples using the E.Z.N.A. Tissue DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Doraville, Georgia, USA), and conventional PCRs, using previously described primers, were performed for diagnosis of M genitalium (target: 16S rRNA gene and, for confirmation, MgPa adhesion (mgpB) gene) and C trachomatis (target: ompA gene).2

For typing of C trachomatis, the ompA gene was PCR amplified, the PCR product was purified and subsequently sequenced and finally about 1100 nucleotides of the ompA sequence was used in a phylogenetic analysis for determination of the genovar, as previously described.8

For typing of M genitalium, the mgpB gene was PCR amplified and sequenced as previously described,9 with some modifications. These modifications included use of 0.4 μM of each of the primers MgPa-1 and MgPa-3 (Scandinavian Gene Synthesis AB, Köping, Sweden) and 2.0 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (PE Biosystems, Branchburg, New Jersey, USA). The PCR programme consisted of an AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase activation step at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 40 sequential cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min and finally an extension step of 72°C for 5 min. All PCR products were stored at 4°C prior to purification. The PCR products were purified using the High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR products were sequenced with the same primers as used in the PCR, utilising the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction v3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) and an ABI Sequencer 3120 (Applied Biosystems), in accordance with the instructions from the manufacturer. Phylogenetic analysis was performed in the same way as for C trachomatis.8

Results

Characterisation of N gonorrhoeae

The results of the antibiotic susceptibility testing of all the N gonorrhoeae isolates (n=31) are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility of 31 Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from Bissau, Guinea-Bissau

| Antibiotic (breakpoints) | Susceptible (%) | Intermediate (%) | Resistant (%) |

| Penicillin G (S≤0.064/R>1.0)* | 5 (16) | 5 (16) | 21 (68)† |

| Ampicillin (S≤0.125/R>3.0) | 10 (32) | 0 | 21 (68)† |

| Cefixime (S≤0.125/R>0.125)* | 31 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Ceftriaxone (S≤0.125/R>0.125)* | 31 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Cefuroxime (S≤0.064/R>1.0) | 5 (16) | 26 (84) | 0 |

| Azithromycin (S≤0.25/R>0.5)* | 31 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Erythromycin (S≤0.25/R>0.5) | 26 (84) | 3 (10) | 2 (6) |

| Ciprofloxacin (S≤0.032/R>0.064)* | 28 (90) | 0 | 3 (10) |

| Spectinomycin (S≤64/R>64)* | 31 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Tetracycline (S≤0.5/R>1.0)* | 8 (26) | 0 | 23 (74) |

| Rifampicin (S≤0.125/R>32) | 24 (77) | 3 (10) | 4 (13) |

| Gentamicin | MIC range: 0.75–6 mg/l | ||

| Kanamycin | MIC range: 8–32 mg/l | ||

Breakpoints (for susceptible (S≤x mg/l) and resistant (R>y mg/l)) according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST; http://www.eucast.org) were used, when available.

All were β-lactamase producing.

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Briefly, the levels of resistance (intermediate susceptibility) to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, rifampicin, ampicillin, tetracycline, penicillin G and cefuroxime were 10% (0%), 6% (10%), 13% (10%), 68% (0%), 74% (0%), 68% (16%) and 0% (84%), respectively. Twenty-one (68%) of the 31 isolates were β-lactamase producing. All isolates were susceptible to cefixime, ceftriaxone, spectinomycin and azithromycin, and the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of kanamycin (8–32 mg/l) and gentamicin (0.75–6 mg/l) were low (no resistance breakpoints exist for these antimicrobials) (table 1).

All the N gonorrhoeae isolates were serotypeable, 20 (64.5%) were determined as serogroup WII/III (PorB1b). These isolates were assigned four different serovars: Bropt (n=16), Bropst (n=2), Bpyvut (n=1) and Brpyvust (n=1). The remaining 11 (35.5%) isolates were determined as serogroup WI (PorB1a). These isolates were assigned two different Ph serovars: Arst (n=10) and Arost (n=1).

The isolates were assigned to 19 different NG-MAST sequence types (STs), of which 16 (84%) have not been previously described (table 2). The ST3176 (n=7), ST783 (n=5) and ST3182 (n=3) were the most prevalent STs. Of these, ST783 has been described in UK, while ST3176 and ST3182 were not earlier described. The remaining 16 isolates were all of different sequence types. Of these, ST1318 has been described in isolates from Arkhangelsk, Russia, Scotland and Canada, and ST2187 in Australia (NG-MAST website: http://www.ng-mast.net).

Table 2.

Distribution of different genotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae among infected women in Guinea-Bissau

| Chlamydia trachomatis (genovar, n=60)* | Mycoplasma genitalium (sequential numbers, n=30)† | Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG-MAST, n=31) |

| G (37%) | 1 (13%) | ST3176 (23%)‡ |

| D (19%) | 2 (10%) | ST783 (16%) |

| F (17%) | 3 (10%) | ST3182 (10%)‡ |

| I (14%) | 4–23 (single isolates 67%) | ST2187 (single isolate, 3%) |

| E (5%) | ST1318 (single isolate, 3%) | |

| J (5%) | ST3177–81 (single isolates, 13%)‡ | |

| H (1.5%) | ST3183–89 (single isolates, 26%)‡ | |

| K (1.5%) | ST3376–77 (single isolates, 6%)‡ |

Based on ompA genotyping.

Based on sequencing of the M genitalium MgPa adhesion (mgpB) gene.

Novel NG-MAST STs.

Notable, the three ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates (all displaying MIC≥1.5 mg/l) were assigned three different STs (ST3181, ST3184 and ST3186) and two different serovars (Bropst, n=2, and Brpyvust, n=1).

Characterisation of C trachomatis

Phylogenetic analysis of the ompA gene sequences from 60 C trachomatis samples revealed that the most frequent genovar was G (22 isolates, 37%), followed by D (19%), F (17%), I (14%), E (5%), J (5%), H (1.5%) and K (1.5%) (table 2). Accordingly, genovar E that is the most prevalent genovar followed by genovar F and genovar D in studies from other settings globally was relatively rare.10–19

Characterisation of M genitalium

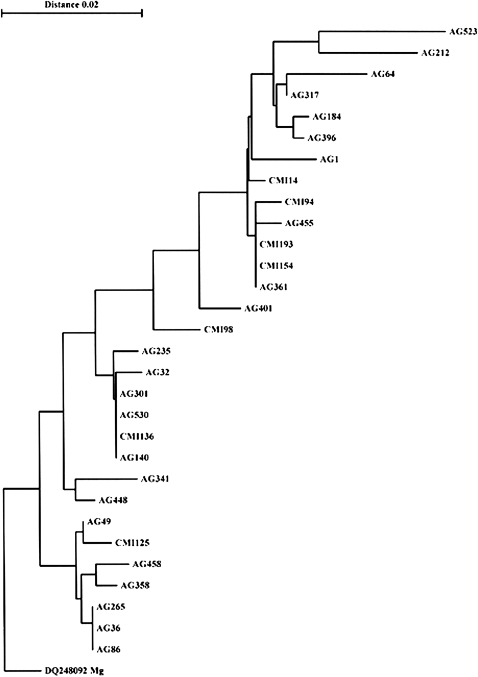

A total of 23 mgpB STs were found among the 30 M genitalium samples. Only three clusters, one with four isolates (‘ST1’) and two containing three isolates (‘ST2’ and ‘ST3’), were detected (figure 1, table 2). The remaining sequence types (‘ST4’–‘ST23’) were only represented by single isolates.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on a 238 nucleotide sequence of the Mycoplasma genitalium MgPa adhesin gene (mgpB) in 30 samples from Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. The same sequence from the M genitalium reference strain G37T (DQ248092) was used for rooting the tree.

Discussion

In the present study, bacterial STIs in Guinea-Bissau were for the first time characterised, phenotypically and genetically, demonstrating highly divergent populations of N gonorrhoeae and M genitalium, and compared with other settings worldwide an unusual genovar distribution for C trachomatis. However, due to the limited number of samples examined, all results need to be interpreted with caution.

The genetic characterisation of the 31 N gonorrhoeae isolates showed a total of 19 different NG-MAST STs, and only three (16%) of these STs have been previously reported, that is, ST783, ST1318 and ST2187 (NG-MAST website: http://www.ng-mast.net). Accordingly, ST783 has been described in UK; ST1318 in Russia,20 Scotland and Canada and ST2187 in Australia (NG-MAST website: http://www.ng-mast.net). The ST3176 (n=7), ST783 (n=5) and ST3182 (n=3), were the most prevalent STs, while the remaining 16 STs were represented by single isolates. The high number of STs represented by single isolates could be a consequence of suboptimal diagnostics, limited and biased sampling, ineffective or non-existing contact tracing, local and recent emergence of new STs and import of strains.

The serological characterisation divided the isolates into 20 (64.5%) serogroup WII/III (PorB1b) isolates and 11 (35.5%) serogroup WI (PorB1a) isolates. The proportion of serogroup WI (PorB1a) isolates was relatively high compared with, for example, Sweden with 26% WI (PorB1a) isolates reported in 2009,21 Italy with 4.1% WI (PorB1a) isolates in 200822 and Russia with 26% WI (PorB1a) isolates in 200720 but lower than described from India with 46.7% WI (PorB1a) isolates in 2007.23 The isolates from Guinea-Bissau were further divided into six different Ph serovars.

As clearly shown, the genetic characterisation (19 NG-MAST STs) had a substantially higher discriminative power than the serovar determination (six serovars). Furthermore, no NG-MAST STs were further subdivided using serovars determination. Accordingly, genetic typing should preferably be used for epidemiological purposes, especially in geographical areas that comprise highly heterogeneous N gonorrhoeae populations.

The antibiotic susceptibility testing displayed relatively high levels of resistance and/or intermediate susceptibility to most antibiotics previously recommended as first line for treatment of gonorrhoea, for example, penicillins, tetracycline, erythromycin and cefuroxime. However, due to the low number of gonococcal isolates (n=31) examined in the present study, the resistance levels need to be interpreted with caution. The resistance level to ciprofloxacin (10%) was relatively low. Nevertheless, at the time of collection of the gonococcal isolates (2006–2008), similar low levels of resistance to ciprofloxacin were shown also in other studies from African countries, for example, from Malawi Mozambique, Central African Republic and Madagascar.24–26 These ciprofloxacin resistance levels were substantially lower than the levels described from many other countries worldwide, where it is now a fear that gonorrhoea may become untreatable in certain circumstances.27 28 However, more recent studies from African countries such as Kenya and South Africa have shown a rapidly increasing resistance to ciprofloxacin.29 30 The slower pace of emerging ciprofloxacin resistance in Guinea-Bissau and several other African countries strains may reflect the fact that fluoroquinolones for treatment of gonorrhoea were not widely used as early in Guinea-Bissau (as well as several other African countries), as in other settings worldwide. Fortunately, all isolates were susceptible to cefixime, ceftriaxone, azithromycin and spectinomycin and had low MICs of gentamicin and kanamycin. Nevertheless, due to the high and increasing resistance levels to many of these antibiotics worldwide, it is essential to enhance the gonococcal antibiotic susceptibility surveillance in African countries as well as globally. In some settings, the resistance levels to previously recommended first-line antibiotics may have remained low and these antibiotics might be valuable to continue to use for treatment of gonorrhoea in these specific settings. Nevertheless, that type of recommendation needs to be supported by sufficient local, appropriate and quality-assured antibiotic susceptibility data.

The phylogenetic analysis of ompA gene sequences in the 60 C trachomatis samples revealed that genovar G (37%) was the most frequent genovar, followed by genovar D (19%) and genovar F (17%). Studies from other settings globally, from 2000 to 2011, have shown that genovar E is the most prevalent followed by genovar F and genovar D.10–19 Furthermore, a longitudinal study over a 9-year period (1988–1996) in Seattle showed similar serovar distribution as reported from other parts of the world and also a stability in the serovar groups over time, except for the more rare serovars I and K.11 Genovar G, which was the most frequent genovar among women in Guinea-Bissau, has in other settings worldwide been the most frequently detected genovar in infections in men who have sex with men.12 17–19 This unusual C trachomatis genovar distribution among women in Guinea-Bissau may reflect the limited sample size, although it can also indicate a local domestic transmission with little importation of strains from abroad.

The ompA sequences were also highly conserved within the genovars. Accordingly, insufficient epidemiological resolution is obtained by ompA sequencing, and novel molecular methods for typing of C trachomatis, such as multiple loci variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST), which both show a substantially higher discriminatory power, are vital.31

Among the 30 M genitalium samples, 67% of the mgpB STs were only represented by single isolates. Only three small clusters, two containing three isolates and one containing four isolates, were identified. This high genetic diversity may suggest that M genitalium is endemic in Bissau and that infection is not due to the distribution of a single strain.

Bacterial STIs are public health problems causing substantial morbidity and economical cost. Furthermore, if undetected and untreated, many bacterial STIs are associated with severe complications and sequelae such as PID, ectopic pregnancy, infertility and facilitated acquisition and transmission of HIV. Ineffective or inadequate detection and/or treatment of these pathogens inevitably contribute also to further transmission of the STIs. Despite that the present study did not show any alarming tendency of N gonorrhoeae strains resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, macrolides and spectinomycin, in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, the rapidly increasing resistance to also these antibiotics worldwide makes it important to introduce quality-assured gonococcal antibiotic resistance surveillance also in Guinea-Bissau and in general in West Africa. Furthermore, due to the high prevalence of HIV in many of the West African countries and the fact that several of these bacterial STIs also facilitate the acquisition and transmission of HIV, more prevalence studies of bacterial STIs as well as national and regional strategies for prevention and control of bacterial STIs in this region are crucial to implement.

In conclusion, the high diversity of N gonorrhoeae, C trachomatis and M genitalium strains in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, may be associated with suboptimal diagnostics, contact tracing, case reporting and epidemiological surveillance. Overall, it is exceedingly difficult to estimate the true burden, distribution and characteristics of STIs in Guinea-Bissau, as well as in many other countries in West Africa. Accordingly, additional studies in other population groups, and in other geographical areas, are crucial to perform in Guinea-Bissau and other countries in the region. The present study compiled with such future studies may form the basis for a national sexual health strategy for prevention, diagnosis and surveillance of STIs in Guinea-Bissau.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Helena Eriksson and Angela Steen for their technical assistance with the serovar determination and antibiotic susceptibility testing. We also thank all staff at the National Public Health Laboratory, the Aguibef clinic and the Centre for Mother and Child Health in Bissau.

Footnotes

To cite: Olsen B, Månsson F, Camara C, et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterisation of bacterial sexually transmitted infections in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, West Africa: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000636. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000636

Contributors: All authors contributed to study design, acquisition and/or analysis of data. All authors also drafted and/or revised critically the present manuscript, as well as have approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was approved by the ethical committees of Lund University, Sweden, and the Ministry of Health, Guinea-Bissau.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.UNDP United Nations Development Programme Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development. New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2010:146 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Månsson F, Camara C, Biai A, et al. High prevalence of HIV-1, HIV-2 and other sexually transmitted infections among women attending two sexual health clinics in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Int J STD AIDS 2010;21:631–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson LF, Lewis DA. The effect of genital tract infections on HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:946–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes JP, Tavira L, Exposto F, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections in patients attending STD and family planning clinics in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Acta Trop 2001;80:261–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labbé AC, Frost E, Deslandes S, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium is not associated with adverse outcomes of pregnancy in Guinea-Bissau. Sex Transm Infect 2002;78:289–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unemo M, Olcén P, Berglund T, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: sequence analysis of the porB gene confirms presence of two circulating strains. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:3741–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unemo M, Fasth O, Fredlund H, et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the 2008 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strain panel intended for global quality assurance and quality control of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance surveillance for public health purposes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:1142–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jurstrand M, Falk L, Fredlund H, et al. Characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis omp1 genotypes among sexually transmitted disease patients in Sweden. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:3915–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hjorth SV, Björnelius E, Lidbrink P, et al. Sequence-based typing of Mycoplasma genitalium reveals sexual transmission. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:2078–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fredlund H, Falk L, Jurstrand M, et al. Molecular genetic methods for diagnosis and characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: impact on epidemiological surveillance and interventions. APMIS 2004;112:771–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suchland RJ, Eckert LO, Hawes SE, et al. Longitudinal assessment of infecting serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis in Seattle public health clinics: 1988-1996. Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:357–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klint M, Ek C, Löfdahl M, et al. Lymphogranuloma venereum prevalence in Sweden among men who have sex with men and characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis ompA genotypes. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:4066–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu MC, Tsai PY, Chen KT, et al. Genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis from clinical specimens in Taiwan. J Med Microbiol 2006;55:301–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao X, Chen XS, Yin YP, et al. Distribution study of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars among high-risk women in China performed using PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism genotyping. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:1185–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taheri BB, Motamedi H, Ardakani MR. Genotyping of the prevalent Chlamydia trachomatis strains involved in cervical infections in women in Ahvaz, Iran. J Med Microbiol 2010;59:1023–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twin J, Moore EE, Garland SM, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis genotypes among men who have sex with men in Australia. Sex Transm Dis 2010;38:279–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quint KD, Bom RJ, Quint WG, et al. Anal infections with concomitant Chlamydia trachomatis genotypes among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:63–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li JH, Cai YM, Yin YP, et al. Prevalence of anorectal Chlamydia trachomatis infection and its genotype distribution among men who have sex with men in Shenzhen, China. Jpn J Infect Dis 2011;64:143–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jalal H, Verlander NQ, Kumar N, et al. Genital chlamydial infection: association between clinical features, organism genotype and load. J med Microbiol 2011;60:881–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unemo M, Vorobieva V, Firsova N, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae population in Arkhangelsk, Russia: phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007;13:873–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unemo M, Olcén P, Johansson E, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae 2009. Annual Report Regarding Serological Characterization and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Swedish Neisseria gonorrhoeae Strains. Örebro, Sweden: National Reference Laboratory for Pathogenic Neisseria, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starnino S, Suligoi B, Regine V, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in parts of Italy: detection of a multiresistant cluster circulating in a heterosexual network. Clin Microbiol Infect 2008;14:949–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khaki P, Bhalla P, Sharma P, et al. Epidemiological analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates by antimicrobial susceptibility testing, auxotyping and serotyping. Indian J Med Microbiol 2007;25:225–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apalata T, Zimba TF, Sturm WA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated from patients attending a STD facility in Maputo, Mozambique. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:341–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown LB, Krysiak R, Kamanga G, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility in Lilongwe, Malawi, 2007. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:169–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao V, Ratsima E, Van Tri D, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains isolated in 2004-2006 in Bangui, Central African Republic; Yaounde, Cameroon; Antananarivo, Madagascar; and Ho Chi Minh Ville and Nha Trang, Vietnam. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:941–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tapsall JW, Ndowa F, Lewis DA, et al. Meeting the public health challenge of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2009;7:821–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohnishi M, Golparian D, Shimuta K, et al. Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea? Detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55:3538–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis DA, Scott L, Slabbert M, et al. Escalation in the relative prevalence of ciprofloxacin-resistant gonorrhoea among men with urethral discharge in two South African cities: association with HIV seropositivity. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:352–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta SD, Maclean I, Ndinya-Achola JO, et al. Emergence of quinolone resistance and cephalosporin MIC creep in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from a cohort of young men in Kisumu, Kenya, 2002 to 2009. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55:3882–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen LN, Herrmann B, Møller JK. Typing Chlamydia trachomatis: from egg yolk to nanotechnology. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2009;55:120–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.