Abstract

Primary intraosseous carcinoma (PIOC) is a rare tumor that has been infrequently reported. Some diagnostic criteria have been proposed to consider a lesion as PIOC: (1) absence of ulcer in the oral mucosa overlying the tumor, (2) absence of another primary tumor at the time of diagnosis and for at least 6 months during the follow-up, and (3) histological evidence of squamous cell carcinoma. The etiology is not clear, although odontogenic embryonic origin has been reported. Probably, PIOC derives from the remnants of odontogenic tissue, either the epithelial rests of Malassez or the remnants of the dental lamina.

Keywords: Intraosseous carcinoma, mandible, odontogenic, primary, squamous cell carcinoma, odontogenic

INTRODUCTION

Primary intraosseous carcinoma is an uncommon entity that has been previously well-recognized. Different considerations may be established concerning its origin. The cellular sources of the epithelial cells may come from the reduced enamel epithelium that surrounds the crown of unerupted teeth, the epithelial rests of Malassez that lie within the periodontal ligament, and the rests of dental lamina inside the fibrous tissue of the gingiva or within the bone.[1]

The mandible and maxilla contain epithelial cells derived from odontogenic embryonic tissues and these cells can give rise to odontogenic cysts, benign tumors and even if rarely malignant epithelial tumors such as primary intraosseous carcinoma arising from odontogenic cyst, malignant ameloblastoma, ameloblastic carcinoma, primary intraosseous carcinoma arising de novo and intraosseous central mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Several cases of malignant transformation of odontogenic cysts or odontogenic tumor have appeared in the literature while primary intraosseous carcinoma arising de novo has been infrequently reported. The diagnostic criteria proposed for primary intraosseous carcinoma are: (1) absence of ulcer formation, except when caused by other factors; (2) histological evidence of squamous cell carcinoma without a cystic component or other odontogenic tumor cells; and (3) absence of another primary tumor on chest radiographs obtained at the time of diagnosis and during a follow-up period of more than 6 months. Prognosis is quite poor, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 30% to 40%. In a recent revision by Thomas et al, survival rates of 1, 2 and 3 years were 75.7%, 62.1%, and 37.8% respectively.[2,3]

CASE REPORT

A female patient aged 42 years reported to the Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology in Kothiwal Dental College and Research Centre with a chief complaint of swelling in lower anterior tooth region since six months. Lesion had initiated as a small swelling which gradually increased in size to present size.

Extra oral examination revealed a firm, large swelling was present in right mandibular region measuring 4×3.3 cms causing facial asymmetry. Unilateral left submandibular lymph node was palpable which was firm in consistency.

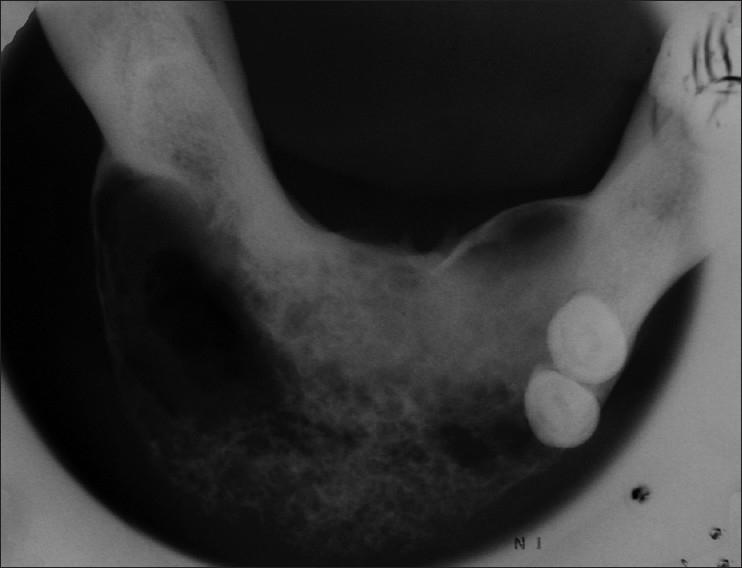

Intra oral examination revealed an asymptomatic, sessile, firm, non-pulsatile swelling measuring 3.8×3cms in 34 to 46 tooth region and 31,32,33,36,37,41,42,43,44,45,46 were clinically missing [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

An asymptomatic, firm swelling present in mandibular 34-46 region

Radio graphically OPG revealed a diffuse radiolucent lesion with ill-defined irregulars borders extended from 34 to 46 tooth region. Occlusal radiograph revealed presence of multilocular radiolucent lesion extending from 34 to 46 tooth region which gave “Honey comb appearance “and causing expansion of labial cortical plate and left lingual cortical portion. In right labial lesion window effect was also seen [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 2.

Orthopantomogram revealed diffuse radiolucent lesion with ill-defined irregulars borders extended from 34 to 46 tooth region

Figure 3.

Occulusal radiograph revealed presence of multilocular radiolucent lesion extending from 34 to 46 tooth region which gave, “Honey comb appearance” and causing expansion of labial cortical plate and left lingual cortical portion. In right labial lesion window effect was seen

Hematological report revealed that patient was anemic and her neutrophils values were raised.

On the basis of clinical and radiological and biochemical investigations the differential diagnosis of the lesion were Squamous cell carcinoma, intra-osseous carcinoma, malignant salivary gland neoplasm and ameloblastic carcinoma of the mandible.

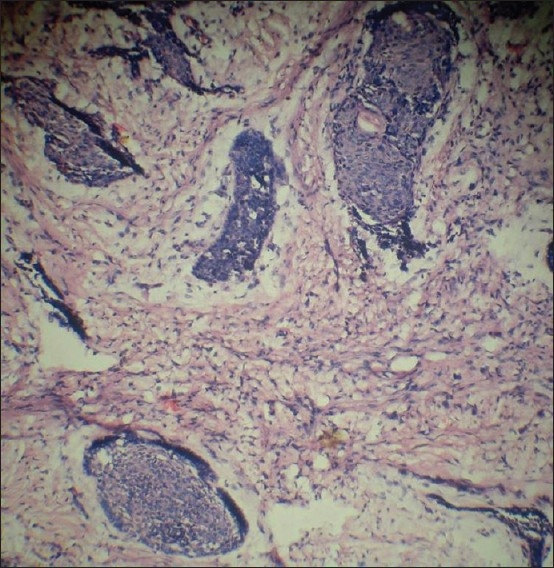

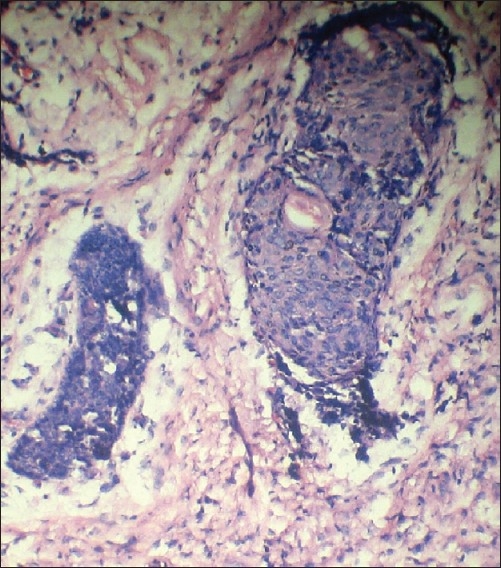

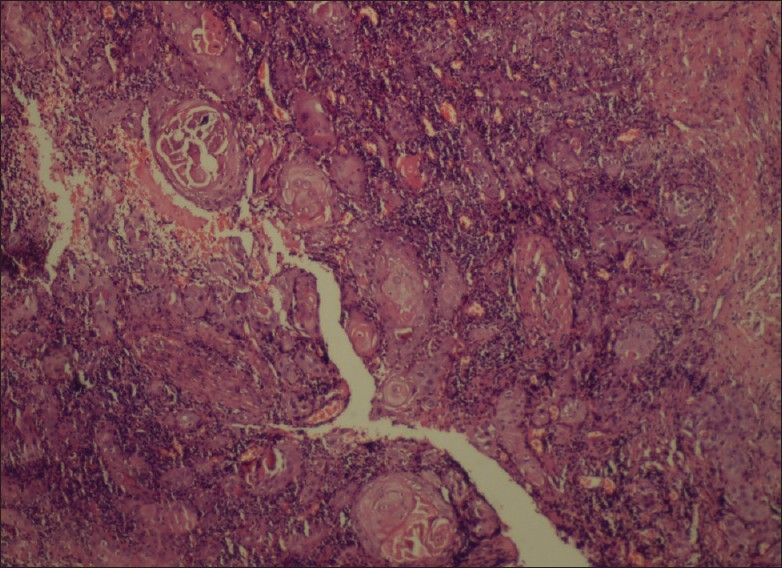

After getting results of laboratory investigations incisional biopsy was performed. Sections from formalin fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for routine histopathological examination. Section stained with H and E revealed the fibro cellular connective tissue stroma interspersed with hyper chromatic tumor islands in the form of cords, and sheets. These tumor island comprising of malignant epithelial cells exhibited cellular and nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli. Multiple vacuolated clear cells with distinct border were also seen within tumor island. Some of the tumor islands were also showing the columnar cells at the periphery of these islands [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 4.

Fibrocellular connective tissue stroma interspersed with hyperchromatic tumor island (H and E stain, 10×)

Figure 5.

Malignant epithelial cells exhibited cellular and nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli. Multiple vacoulated clear cells were also seen within tumor island (H and E stain, 10×)

Such histopathological findings were confused with some other lesions such as intra-osseous muco-epidermoid carcinoma, clear cell odontogenic carcinoma and ameloblastic carcinoma.

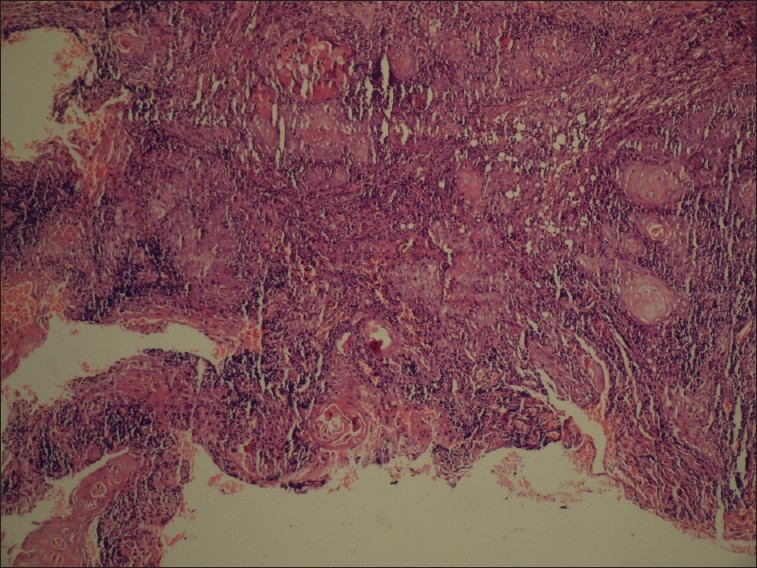

After finding such diversity in the histopathological findings have seen in the deep sections of the lesion and found some additional features such as: the tumor islands forming the solid nests and cords showing dysplasia. Some islands were also showing the areas of squamous differentiation with keratinization in the form of whorls and resembling to keratin pearls as seen in Squamous cell carcinomas. Some areas were also showing the presence of bony trabeculae [Figures 6 and 7].

Figure 6.

Areas showing keratinization in the form of pearls resembling squamous cell carcinoma (H and E stain, 10×)

Figure 7.

Areas showing keratinization in the form of pearls resembling squamous cell carcinoma (Higher magnification) (H and E stain, 20×)

So on the basis of overall clinical, radiographical and histopathological features of the lesion were suggestive of “Primary Intra Osseous Carcinoma”.

Patient was advised to have segmental mandibular resection plus post-operative radiotherapy but she refused to undergo surgery.

DISCUSSION

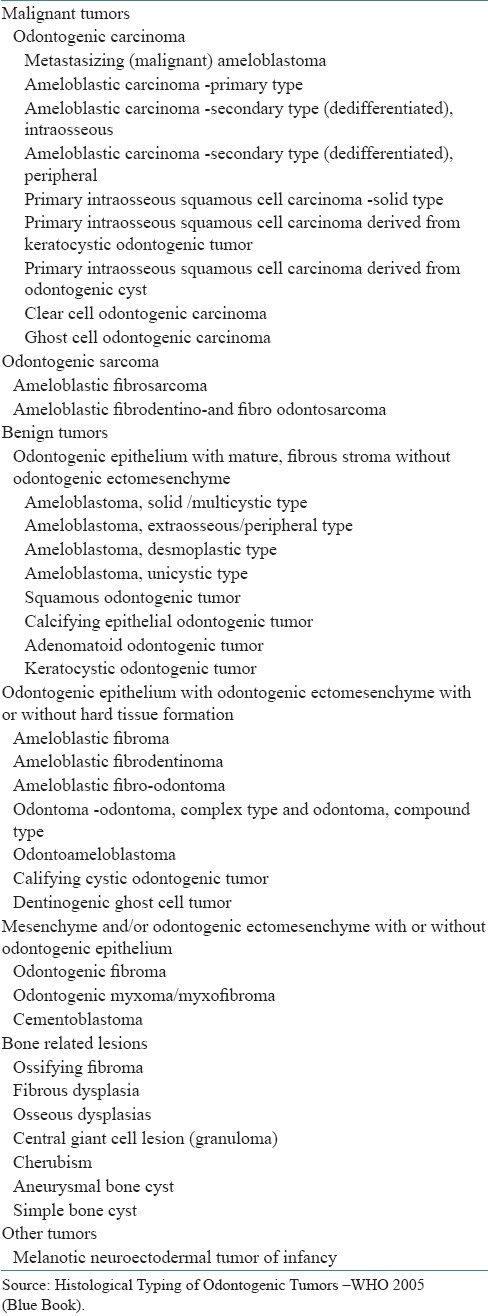

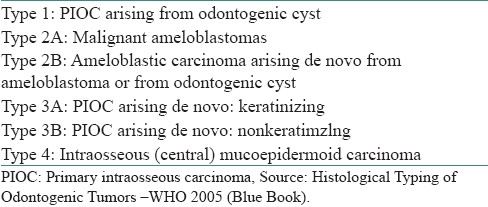

Primary intraosseous carcinoma is an uncommon neoplasm. According to the most recent edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification for histological typing of odontogenic tumors [Table 1], it is defined as a squamous cell carcinoma arising within the jawbone without connection to the oral mucosa, probably from odontogenic epithelial residues. PIOC includes carcinomas arising de novo and from ameloblastomas or odontogenic cysts. This tumor was firstly described by Loos in 1913. Pindborg coined the term PIOC in the first edition of the WHO classification for histological typing of odontogenic tumors. Elazy subsequently recommended a modification of this WHO classification after reviewing a sample of subjects with PIOC. Slootweg and Muller further modified Elazy's classification taking into account the various possible origins of PIOC. Waldron and Mustoe later suggested adding intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma to this classification [Table 2].[4–8] This was based on the rationale that despite the fact that these growths are usually considered salivary gland tumors, microscopically identical with salivary mucoepidermoid carcinoma, there is evidence to suggest that a number of these intraosseous tumors originate in the epithelial lining of odontogenic cysts.

Table 1.

World health Organization classification 2005

Table 2.

Modified classification of PIOC

Reviewing the English-language literature and excluding cases with ulceration of the oral mucosa and those where a search for another primary site had not been conducted, 40 cases of de novo PIOC were identified between 1970 and 2004. Affecting more males than females (M:F= 3:2), PIOC is more frequent in the sixth and seventh decades of life.[9]

It occurs more frequently in the mandible (especially the posterior section) than in the maxilla. In the classification proposed by Waldron and Mustoe [Table 2].[6,8]

Our case was a type-3a PIOC, based on the representative histological findings of the individual cell keratosis. Discrimination between type-3a and 3b PIOCs is based on the former lesion possessing keratin pearls and/or individual keratosis, whereas these features are absent in the latter. The WHO has published criteria to differentiate PIOC from other primary and metastatic squamous cell carcinomas of the jawbone.

Additional criteria for categorizing a lesion as PIOC, such as: (a) intact oral mucosa before diagnosis; (b) microscopic evidence of squamous cell carcinoma without a cystic component or other odontogenic tumor cells; and (c) absence of another primary tumor on chest radiographs obtained at the time of diagnosis and during a follow-up period of more than 6 months, have been suggested by Suei et al.[10,11]

Therefore, exclusion of the possibility of metastatic lesion from a distant primary tumor is always necessary for the final diagnosis of PIOC. Metastatic carcinoma of the jawbone is mainly derived from the thyroid, kidney, prostate, and lung.

The possibility of metastasis can be eliminated by a careful review of the history and comprehensive systemic evaluation. Furthermore, the finding of an intact mucosa in the present case made the possibility of direct extension of squamous cell lesions from the oral mucosa appear unlikely.[12,13]

Although the clinical features of PIOCs are non- specific, Zewetyenga et al, have reported that principal manifestations for half of a number of samples of de novo.[14]

PIOC cases were sensory disturbances like paraesthesia and numbness, mimicking facial neurological problems. Given the solely neurological disturbances, and the absence of any obvious mucosal abnormalities within the oral cavity, especially in the case of the early lesion, the first professional consultation may be with the family dentist, increasing the probability of delayed diagnosis. Delays in correct diagnosis, ranging from a few weeks to as long as 18 months, have been reported by To et al.[15]

Clearly, this will worsen prognosis; hence, it is important to consider intraosseous carcinoma in the jawbone in the differential diagnosis for all cases of facial paraesthesia and numbness to facilitate the early identification of PIOC and enabling prompt institution of suitable treatment. Radiographic examination is one of the most effective methods for detecting PIOCs.

A lesion that is completely surrounded by bone can be regarded as of intraosseous origin. CT scan can also facilitate correct diagnosis. However, for some particular circumstances, as in the presented case, the radiographic artifact caused by the serious secondary irradiation owing to the intraoral metal prosthesis greatly limits the usefulness of this scanning modality in terms of adequate diagnosis. Panoramic radiography, a simple, effective and low-cost examination, a standard facility that is generally available to the dental department of a teaching hospital, can be used in its stead.

In the review by To et al, 46% of the PIOC patients survived for periods ranging from 6 months to 5 years. There is insufficient information, however, to distinguish the survival times for the different PIOC types listed in Table 1. However, there appears to be a difference in survival rates comparing type-1 and type-3 PIOCs. Eversole et al, reported a 53% 2 year survival rate for the type 1 entity, whereas Elazy demonstrated a 40% 2-year survival rate for the de novo lesion. These results indicate that PIOCs originating from odontogenic cysts have a better prognosis than the de novo lesions.[6,15,16]

Radical surgery with/without post-operative radiotherapy is recommended for management of de novo PIOC. Other treatment modalities, such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy, should be considered only for lesions that cannot be surgically controlled. For our patient, it was advised to have segmental mandibular resection plus post- operative radiotherapy but she refused to undergo further treatment. Despite that, she was alive.

Since PIOC essentially occurs only in the tooth-bearing areas of the jawbone, the hypothesis of odontogenic epithelial origin is theoretically acceptable, except in the maxillary incisive canal.

At termination of the odontogenesis, remnants of the odontogenic epithelium, derived from different origins such as the tooth germ, reduced enamel epithelium, Hertwig's sheath and the dental lamina, remain in the oral tissues as epithelial rests. Occasionally, owing to some unknown stimuli, these epithelial rests are activated and, either alone or in conjunction with mesodermal tissues, they then proliferate and develop into odontogenic cysts or carcinomas.[16,17]

In 2006 Risa Chaisuparat et al, reported 6 new cases of PIOC, affecting 4 female and 2 male patients with a mean age of 56.2 years. Two cases involved the maxilla and 4 cases occurred in the mandible. The typical radiographic presentation was that of a radiolucent lesion with well or ill-defined margins. Histopathologically, 4 cases were diagnosed as well differentiated keratinizing PIOC arising from previous odontogenic cysts (2 odontogenic keratocysts and 2 periapical cysts). The remaining 2 cases were poorly differentiated nonkeratinizing PIOC, which appeared to arise de novo.

In 2007 Raúl González- García et al, reported case on Primary intraosseous carcinomas of the jaws arising within an odontogenic cyst, ameloblastoma with reconstruction considerations.[17]

By Suei et al,[16–18] the classic oral mucosa squamous cell carcinomas, the risk factors of alcohol, tobacco or betel- quid abuse are usually not present in PIOC patients. The most common risk factor for inducing neoplastic formation of PIOC is assumed to be a reactive inflammatory stimulus, with/without a predisposing genetic cofactor.

It was suggested that the tumor may involve not only the bone marrow space, but also the periodontal and the sub epithelial soft-tissue analogues as epithelial rests may exist in all three. To account for the possibility that a squamous cell carcinoma of odontogenic origin could also arise in the periodontal and sub epithelial soft-tissue spaces, therefore the term odontogenic squamous cell carcinoma was proposed as a replacement for PIOC, whereas the term intraosseous would be used to denote origin only in the bone-marrow space.[18–20]

Since the presented example was found in the edentulous mandible of our patient, this excluded involvement of the periodontal space, and indicated association with both the bone marrow and sub epithelial soft-tissue analogue.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kramer IR, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. 2nd ed. Berlin: World Health Organization, Springer- Verlag; 1992. Histologic typing of odontogenic tumors; pp. 112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas G, Sreelatha KT, Balan A, Ambika K. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the mandible: A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:82–6. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas G, Pandey M, Mathew A, Abraham EK, Francis A, Somanathan T, et al. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaw: Pooled analysis of world literature and report of two new cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:349–55. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loos D. Central epidermoid carcinoma of the jaw. Dtsch Monatschr Zahnheik. 1913;31:308. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pindborg JJ, Kramer IR, Torloni H. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1971. Histologic typing of odontogenic tumors, jaw cysts and allied lesions; pp. 35–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elazy RP. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:299–303. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slootweg PJ, Muller H. Malignant ameloblastoma or ameloblastic carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:168–76. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldron CA, Mustoe TA. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the mandible with probable origin in an odontogenic cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:716–24. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Punnya A, Kumar GS, Rekha K, Vandana R. Primary intraosseous odontogenic carcinoma with osteoid/dentinoid formation. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:121–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vander Waal RI, Buter J, van der Waal I. Oral metastases: Report of 24 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(02)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suei Y, Tanimoto K, Taguchi A, Wada T. Primary intraosseous carcinoma: Review of the literature and diagnostic criteria. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:580–3. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ide F, Shimoyama T, Horie N, Kaneko T. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the mandible with probable origin from reduced enamel epithelium. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:420–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavalcante AS, Carvalho YR, Cabral LA. Tender mandibular swelling of short duration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:70. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.120896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwetyenga N, Pinsolle J, Rivel J, Majoufre-Lefebvre C, Faucher A, Pinsolle V. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaws. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:794–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.To EH, Brown JS, Avery BS, Ward-Booth RP. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaws: Three new cases and a review of the literature. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:19–25. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eversole LR, Duey DC, Powell NB. Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma: A clinicopathologic analysis. Arch Otolaryngol, Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:685–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890060083017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-García R. Primary intraosseous carcinomas of the jaws arising within an odontogenic cyst, ameloblastoma, and de novo: report of new cases with reconstruction considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suei Y, Taguchi A, Tanimoto K. Recommendation of modified classification for odontogenic carcinomas. Med Hypotheses. 2004;62:382–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang JW, Luo HY, Li Q, Li TJ. Primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma of the jaws. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1834–40. doi: 10.5858/133.11.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallego L, Junquera L, Villarreal P, Fresno MF. Primary de novo intraosseous carcinoma: Report of a new case. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:e48–51. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]