Abstract

Context:

Use of diluted dish washing solution (DWS) has been experimented successfully as a substitute for xylene to deparaffinize tissue sections during hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining.

Aims:

(1) Test the hypothesis that xylene- and methanol-free sections (XMF) deparaffinized with diluted DWS are better than or at par with conventional H and E sections. (2) To compare the efficacy of xylene-free sections with the conventional H and E sections.

Settings and Design:

Single blinded experimental study.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty paraffin blocks were considered. One section was stained with conventional H and E method (Group A) and the other with XMF H and E (Group B). Slides were scored for parameters; nuclear staining, cytoplasmic staining (adequate = score1, inadequate = score0), uniformity, clarity, crispness (present = score1, absent = score0). Score >/= 2 was inadequate for diagnosis and 3-5 was adequate for diagnosis.

Statistical analysis used:

Z test.

Results:

Adequate nuclear staining, 96.66% sections in group A and 98.33% in Group B (Z = 0.59, P>0.05); adequate cytoplasmic staining, 93.33% in group A and 83.33% in Group B (Z = 1.97, P<0.05); uniform staining, 70% in group A, 50% in group B (Z = 1.94, P<0.05), clarity present in 85% of group A, 88.33% of group B sections (Z = 0.27, P>0.05), crisp staining in 76.66% in group A and 83.33% in Group B (Z = 1.98, P<0.05), 88.33% Group A sections stained adequately for diagnosis as compared with 90% in Group B (Z = 0.17, P>0.05).

Conclusion:

Xylene- and methanol-free H and E staining is a better alternative to the conventional H and E staining procedure.

Keywords: Deparaffinization, eosin, hematoxylin, liquid dish washing soap, xylene-free staining

INTRODUCTION

The hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stain forms the backbone of daily pathological diagnostic work. The basic material for the bulk of daily diagnostic work in a pathology laboratory is the paraffin section, usually stained with H and E.[1] H and E is a universal stain and is a primary contrast method in medical diagnosis of biopsy specimen. H and E staining is remarkably robust. It is used to discriminate between a broad range of cytoplasmic, nuclear and extracellular matrix features.[2] This staining procedure has remained unchanged for over 150 years.[1] Apart from hematoxylin and eosin, the components in the H and E staining procedure are the xylene and graded alcohols. These chemicals are used to carry out the intermediate steps of rehydration and dehydration of tissue sections during the staining. The lacunae however that continue to persist in this age-old procedure are the cost containment, toxicity, problem of disposal of the hazardous chemicals; xylene and methanol, and a polluted working environment.[1]

Exposure to xylene in a laboratory occurs during tissue processing, deparaffinization of tissue sections, cover slipping, cleaning tissue processors and recycling. Exposure to methanol occurs during tissue processing and dewaxing the sections before staining.[3]

In the quest to eliminate the use of xylene from the laboratory, numerous substitute chemicals like limonene reagents, aliphatic hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, vegetable oils, olive oil, and mineral oil substitutes have been utilized. However, these chemicals were used to substitute xylene as a clearing agent during routine processing, while the exposure and handling of xylene is maximum during dewaxing of the tissue sections.[3]

Basic aim in any field of life sciences is to utilize eco-friendly chemicals which are nontoxic, less biohazardous, and are economical. Liquid dish washing soap (DWS) forms a part of the day-to-day household job. It is a detergent liquid used to clean the greasy utensils in a kitchen.

The innovative concept of using liquid dish washing detergent to dewax the tissue sections by eliminating both xylene as well as alcohol from the staining task was experimented by Falkeholm et al.[1]

Aim

Therefore, an experimental, cross-sectional study was carried out,

To test the hypothesis that xylene- and methanol-free (XMF) sections deparaffinized with diluted DWS are better than or at par with the conventional H and E-stained sections.

To compare the efficacy of XMF sections with the conventional H and E sections in producing adequate H and E staining.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was carried out in the Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology. Sixty paraffin blocks of the routine biopsy specimen were retrieved from the Department.

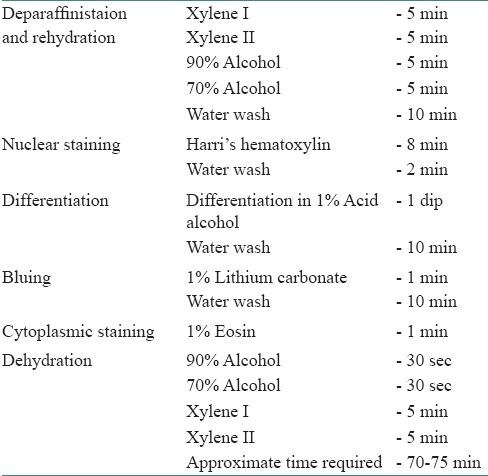

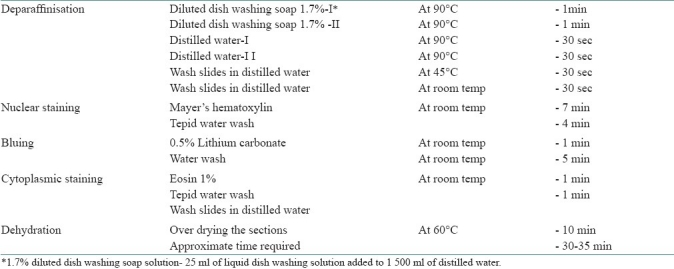

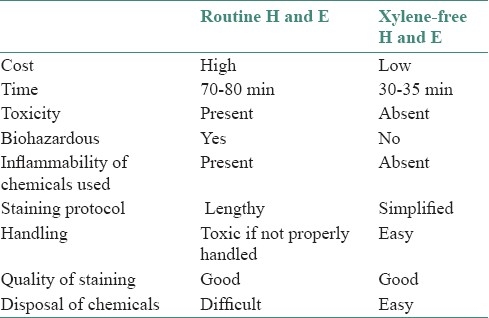

Two paraffin sections of 4 microns each were cut from each of the 60 paraffin blocks of routinely processed tissue specimen. One was stained with the conventional (routine) H and E staining method. The standard time period of the H and E staining procedure ranges from 70 to 75 minutes [Table 1] and the other section was stained with the XMF H and E staining method. This H and E staining procedure is completed in 30 to 35minutes [Table 2]. Thus, a total of 120 sections were studied.

Table 1.

Routine (conventional) H and E staining procedure

Table 2.

Xylene and alcohol free H and E staining procedure

Sixty tissue sections stained with conventional H and E—(Group A) and 60 sections stained with the XMF method—(Group B) were coded. A randomized mix of 120 sections gave 60 matched pairs. Each section was scored and analyzed by a single oral pathologist who was blinded.

H and E-stained sections were graded based on the parameters of nuclear staining (Adequate = score 1, Inadequate = 0), cytoplasmic staining (Adequate = score 1, Inadequate = score 0), clarity of staining (Present = score 1, absent = score 0), uniformity of staining (Present = score 1, absent = score 0), and crispness of staining (Present = score 1, absent = score 0). The scores for each slide were totalled. A score of ≥ 2 was graded as inadequate for diagnosis, slides with score 3-5 were assigned as adequate for diagnosis.

RESULTS

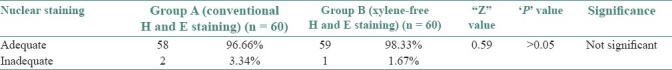

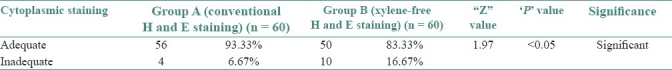

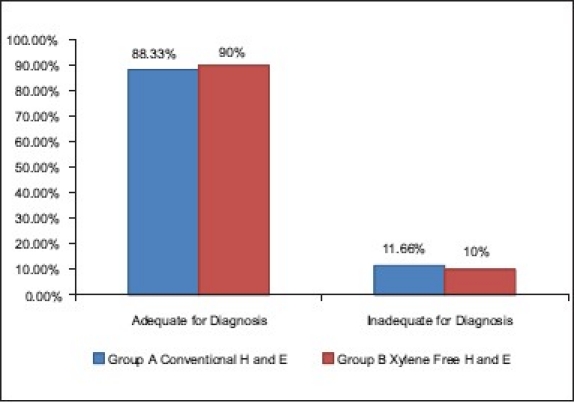

Adequate nuclear staining was noted in 96.66% of sections of group A as compared with 98.33% in Group B (Z = 0.59, P>0.05) [Table 3], adequate cytoplasmic staining was noted in 93.33% of sections in group A as compared with 83.33% in Group B (Z = 1.97, P<0.05) [Table 4], clarity was present in 85% of group A and in 88.33% of group B sections (Z = 0.27, P>0.05) [Table 5], uniform staining was present in 70% of group A and in 50% of group B (Z = 1.94, P<0.05) [Table 6], and a crisp staining was seen in 76.66% of sections in group A as compared with 83.33% in Group B (Z = 1.98, P<0.05) [Table 7]. The staining was found to be adequate for diagnosis in 88.33% of Group A sections as compared with 90% in Group B (Z = 0.17, P>0.05) [Table 8].

Table 3.

Adequacy of nuclear staining in group A and B

Table 4.

Adequacy of cytoplasmic staining in group A and B

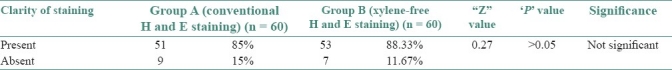

Table 5.

Clarity of staining in group A and B

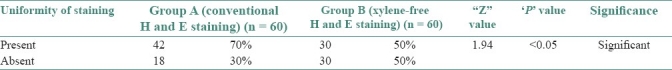

Table 6.

Uniformity of staining in group A and B

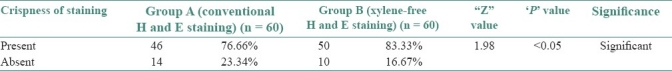

Table 7.

Crispness of staining in group A and B

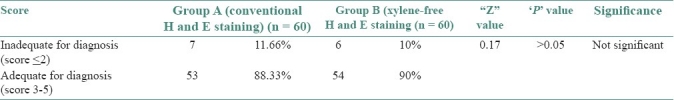

Table 8.

Scores for the adequacy for diagnosis of the stained sections in group A and B

DISCUSSION

Xylene forms an inseparable part of a pathology laboratory. The historical use of xylene in the histology laboratory is an example of a failed substitution. Starting as the safest alternative to dangerous chemicals such as aniline oil, benzene, chloroform, dioxane, and toluene in the 1950s, by the 1970, there were great concerns about its safety. Toxic effects of xylene include acute neurotoxicity, cardiac and kidney injuries, fatal blood dyscrasias, skin erythema, drying, scaling, and secondary infection.[3,4] Methanol is also known to be toxic. The knowledge of xylene toxicity resulted in 41% of US histology laboratories to use xylene substitutes. Countries like US have provisions like OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) and ACGIH (American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienist). These bodies have established standards for biological exposure limits, for monitoring exposure and managing the disposal and recycling of xylene.[3] However, in most of the developing countries, especially in India, we find no such provisions. The institutional and private pathology laboratories in developing countries have neither any mechanism for monitoring the exposure nor any standardized methods for disposal of xylene.

Therefore, any technique that minimizes the use of xylene by using non-biohazardous substitutes, reduces staining time, and does not compromise the staining quality will be very valuable for diagnostic reasons as well as for maintaining a healthy laboratory environment, thereby minimizing the risk to the laboratory personell. Thus, in an effort to improve the working conditions in a histopathology laboratory, we investigated the less toxic, cheap, easily available diluted liquid DWS as a deparaffinizing agent for H and E staining method.

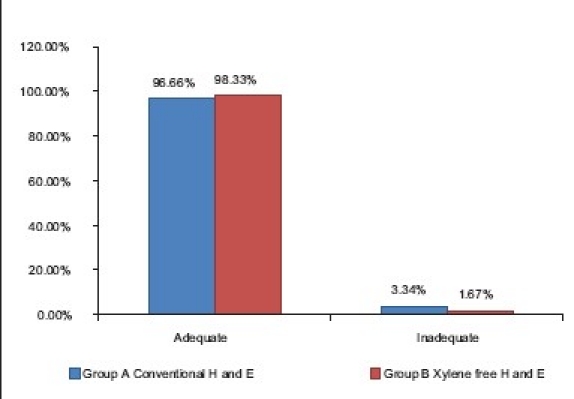

The results showed that of the 60 sections studied, 98.33% of the Group B (XMF) slides showed adequate nuclear staining as compared with 96.66% of the conventional H and E [Table 3]. The difference was not statistically significant (Z = 0.59, P>0.05) suggesting that there was no difference in the two staining methods in producing adequate nuclear staining [Graph 1] [Figure 1]. The nuclear staining in the xylene-free staining method was done using Mayer's hematoxylin. Commercially available Mayer's hematoxylin (Yucca Diagnostics, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India) was used. It is a progressive stain.[5] Progressive staining can be easily controlled, with less chances of overstaining. There is no differentiation required (thereby saving time) unlike with the regressive hematoxylin stains like Harri's and Delafield's hematoxylin. Moreover, incomplete differentiation following regressive staining can result in inadequate cytoplasmic staining due to the binding of aluminium hematin in the cytoplasm.[6] The degree of crispness of nuclear staining with Mayer's was found to be nearly equivalent to Harri's hematoxylin.

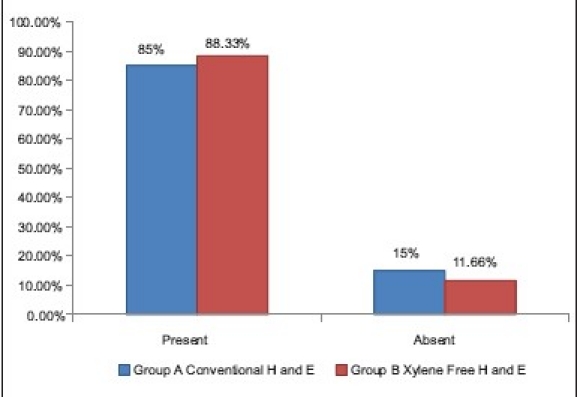

Graph 1.

Comparison of adequacy of nuclear staining in group A and B

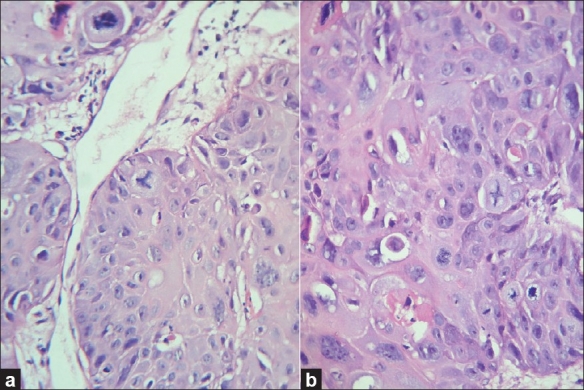

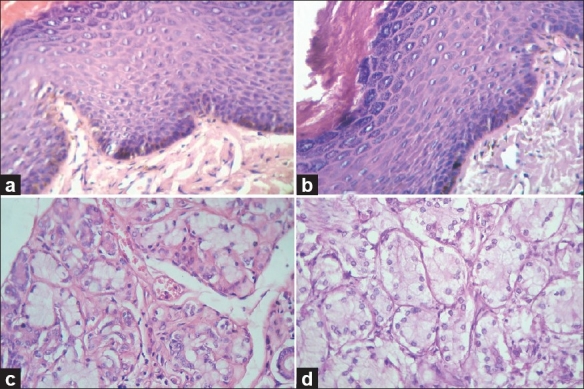

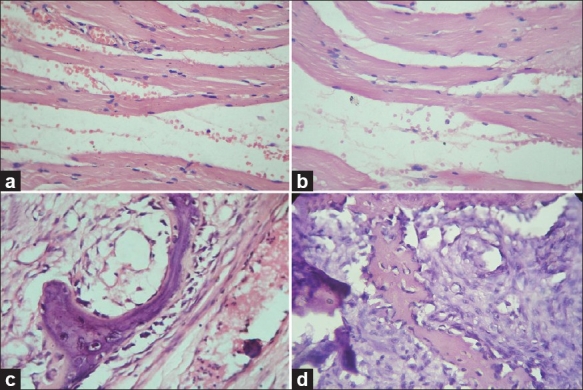

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph showing adequacy and clarity of nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (a) Routine H and E staining, (H and E, 100×), (b) Xylene- and alcohol-free H and E staining, (H and E, 100×)

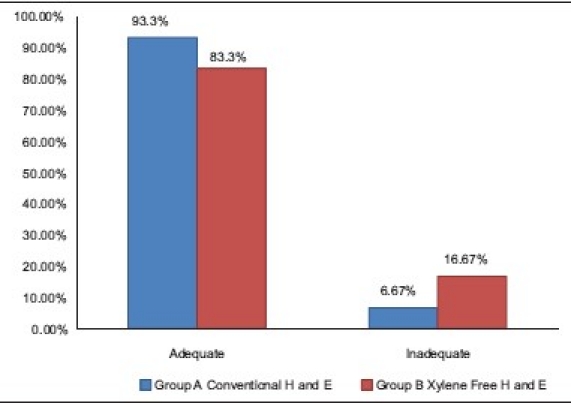

83.33% of XF sections had adequately stained cytoplasm as compared with the 93.33% of the conventional H and E sections (Z = 1.97, P<0.05) [Table 4]. A statistically significant downgradation of cytoplasmic staining was noted in the xylene-free H and E-stained sections [Graph 2]. Commercially available water-soluble 1% Eosin Y (Yucca Diagnostics, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India) was used with the XMF staining. Eosin Y brought out the maximum details of the cytoplasm in 50 of 60 XMF sections studied [Figure 1]. Ten sections showed a deteriorated cytoplasmic stain. The sections appeared bluish [Figure 2a]. Eosin is an acidic dye with optimum staining occurring at a pH of 5.2 to 5.4. It will rinse out in any alkaline solution.[7] The pH of eosin was found to be adequate. The other sources of alkalinity was the tap water wash used before and after the eosin staining step. Therefore, the tap water was analyzed for the pH. It had a pH of 7.01. Lithium carbonate was another source of alkalinity. Increase of alkalinity had probably resulted in eosin being washed out, resulting in a light staining. The pH of tap water was found to be adequate for bluing and hence lithium carbonate was eliminated. This resulted in overcoming this problem.

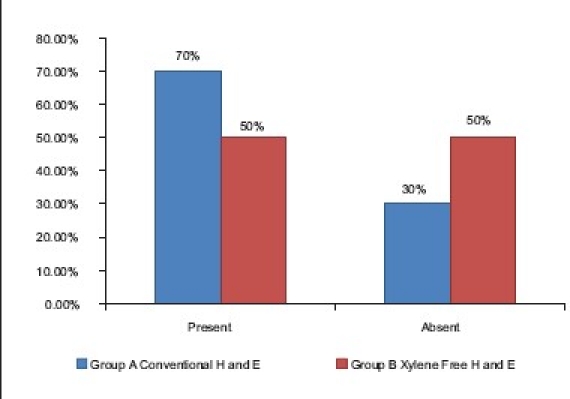

Graph 2.

Comparison of adequacy of cytoplasmic staining in group A and B

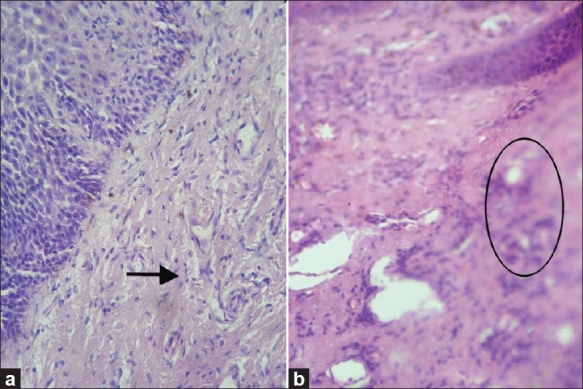

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing (a) deterioration of cytoplasmic staining in (10 of 60) xylene- and alcohol-free sections. Xylene- and alcohol-free H and E, 40×, (b) out-of-focus areas in the xylene- and alcohol-free H and E-stained sections, (H and E, 10×)

The clarity with XMF sections was 88.33% as compared with 85% of clarity in conventional (routine) H and E staining [Table 5]. No statistically significant difference was noted in the two staining methods followed, suggesting that the XMF H and E are at par with conventional H and E in producing clarity in staining [Graph 3]. Xylene is a known carcinogen with numerous biotoxic effects. Histology, however, continues to use large quantities of organic solvents and remains a major producer of organic solvent effluent.[3] The diluted liquid DWS is an extremely cheap, nontoxic substitute for xylene. It is readily available in any stationery stores. The liquid DWS is composed of sodium laureth sulfate, sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate, cocamidopropyl betaine, and nonionic surfactants. These components are anionic surfactants commonly used in detergent soaps and shampoos.[8] These chemicals form a part of the products which are used daily. Their concentration in these products is already well monitored by the manufacturing companies. Moreover, we are diluting only 25 ml of the liquid DWS in 1 500 ml of distilled water. Thus, there are meager chances of this product being toxic to the laboratory personnel.

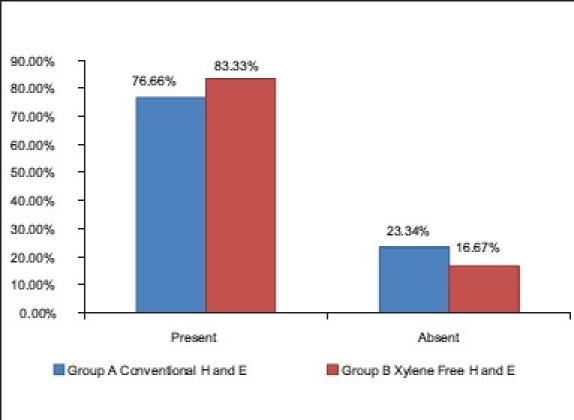

Graph 3.

Comparison of clarity of staining in group A and B

The uniformity of the stained section was downgraded significantly in the XMF sections as compared with the conventional H and E sections (70%) (Z = 1.94, P<0.05). This was shown in the results which showed only 50% of the XMF sections to be uniformly stained [Table 6] [Graph 4]. Out-of-focus areas seen in the section compromised the uniformity. This was a consistent problem encountered as seen in the Figure 2b. Out-of-focus areas can be due to the reasons like tear or rip of section, introduction of extraneous tissue, unclean blade, dirty microscopic lenses, thick section, and moisture on coverslip.[9] All of these reasons were ruled out. Careful scrutiny and retrospective analysis of the staining procedure led to an important conclusion that the xylene-free staining procedure is highly temperature sensitive. The diluted 1.7% liquid DWS-I and II and the distilled water I and II had to be strictly maintained at 90°C. A slight drop in the temperature failed to deparaffinize the sections completely. This resulted in microscopic amounts of residual wax on the tissue sections that resulted in out-of-focus areas.

Graph 4.

Comparison of uniformity of staining in group A and B

83.33% of the XMF sections revealed a crisp staining as compared with 76.66% of the conventional H and E stain [Table 7]. The XMF sections showed a significant upgradation in crispness as compared with the conventional H and E stain (Z = 1.98, P<0.05) [Graph 5]. The combination of 1.7% liquid DWS along with water-soluble Mayer's hematoxylin and eosin Y brings about an ideal degree of crispness. Deparaffinization with diluted liquid DWS is achieved in only 4 minutes unlike 20 minutes required for deparaffinization with xylene and alcohol in the routine H and E staining. This saves time and simplifies the staining procedure [Figures 3 and 4].

Graph 5.

Comparison of crispness of staining in group A and B

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph showing the crisp staining of epithelium, connective tissues, and glandular tissue. (a) Epithelium and connective tissue stained with routine H and E staining, (H and E, 10×), (b) Epithelium and connective tissue stained with xylene- and alcohol-free H and E staining, (H and E, 10×), (c) Glandular stained with routine H and E staining, (H and E, 40×), (d) Glandular tissue stained with xylene- and alcohol-free H and E staining, (H and E, 40×)

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph showing the crisp staining of muscle and bone tissues. (a) Muscle tissue stained with routine H and E staining, (H and E, 40×), (b) Muscle tissue stained with xylene- and alcohol-free H and E staining, (H and E, 40×), (c) Bone tissue stained with routine H and E staining, (H and E, 40×), (d) Bone tissue stained with xylene- and alcohol-free H and E staining, (H and E, 40×)

When the scores were totaled, 90% of the XMF H and E-stained sections were found to be adequate for diagnosis as compared with 88.33% of the slides stained with routine H and E (Z = 0.17, P>0.05) [Table 8] [Graph 6]. Falkeholm et al.[1] found that the xylene-free sections were ranked as good as or better than their conventional counterparts in 74% of the comparisons, and poorer in 26%. Beusa and Peshkov[3] demonstrated that 1.7% dishwasher soap aqueous solution at 90°C before staining and overdrying the sections after staining will eliminate xylene from the staining task. The advantages of the xylene- and alcohol-free H and E staining procedure are listed in Table 9.

Graph 6.

Comparison of staining for adequacy of diagnosis in group A and B

Table 9.

Advantages of xylene- and alcohol-free H and E staining method

CONCLUSION

Thus, the present study shows that XMF staining procedure carried out using a simple diluted liquid dish washing soap solution is at par with the conventional H and E procedure. It produces a quality staining with sufficient clarity and a crisp nuclear and cytoplasmic staining. It also has added advantages of being nontoxic, economical, nonflammable, nonhazardous, no problem of disposal, reduces staining time, and is easy to handle.

SCOPE FOR THE STUDY

The xylene- and alcohol-free H and E-stained sections need to be evaluated after a time period of 1 year or so in order to see for the stability in the staining of tissue section and to see that the sections have not faded.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to Dr. Hemant Pawar, Assistant Professor, Department of Preventive & Community Medicine, Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, Loni, for the statistical work-up. We are also thankful to Dr. Someshwar Golgire, postgraduate in the Department of Oral Pathology, VPDC, Kavalapur, Sangli, and to Mr. Mohan Jagtap, Laboratory Technician in our Department for their assistance during the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Falkeholm L, Grant CA, Magnusson A, Möller E. Xylene-Free Method for Histological Preparation: A Multicentre Evaluation. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1213–21. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Q Imaging Camera Application Notes. H and E stain tissue documentation. [Internet] [Last cited on 2010 Dec 24]. Available from http://www.qimaging.com/support/pdfs/he_technote.pdf .

- 3.Buesa RJ, Peshkov MV. Histology without xylene. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2009;13:246–56. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandyala R, Raghavendra SP, Rajasekharan ST. Xylene: An overview of its health hazards and preventive measures. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2010;14:1–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.64299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alan Stevens, Ian Wilson. Chapter 6. The Haematoxylins and Eosin. In: Bancroft JD, Stevens A, editors. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 4th Ed. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 1996. pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill G. H&E staining: Oversights and Insights. [Internet] [Last cited on 2010 Dec 24]. Available from: www.dako.com/08066_12may10_webchapter13.pdf .

- 7.Ellis R. Problems in Histopathological Technique. [Internet] [Last cited on 2010 Dec 24]. Available from: www.ihcworld.com/royellis/problems/problem25.htm .

- 8. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec 24]. Available from: Internet source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detergent .

- 9.Hamill JR, Spencer S, Morgan . New York: Springer Link; 2009. [Last cited on 2010 Dec 24]. On Atlas of Mohs and Frozen Section Cutaneous Pathology [Internet] Available from: http://www.books.google.co.in/books. Chapter 20, Histotechnique and Staining Troubleshooting . [Google Scholar]