Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of hyperosmolality on the performance of, and the collateral blood flow to, ischemic myocardium. The myocardial response to mannitol, a hyperosmolar agent which remains extracellular, was evaluated in anesthetized dogs. Mannitol was infused into the aortic roots of 31 isovolumic hearts and of 15 dogs on right heart bypass, before and during ischemia. Myocardial ischemia was produced by temporary ligation of either the proximal or mid-left anterior descending coronary artery.

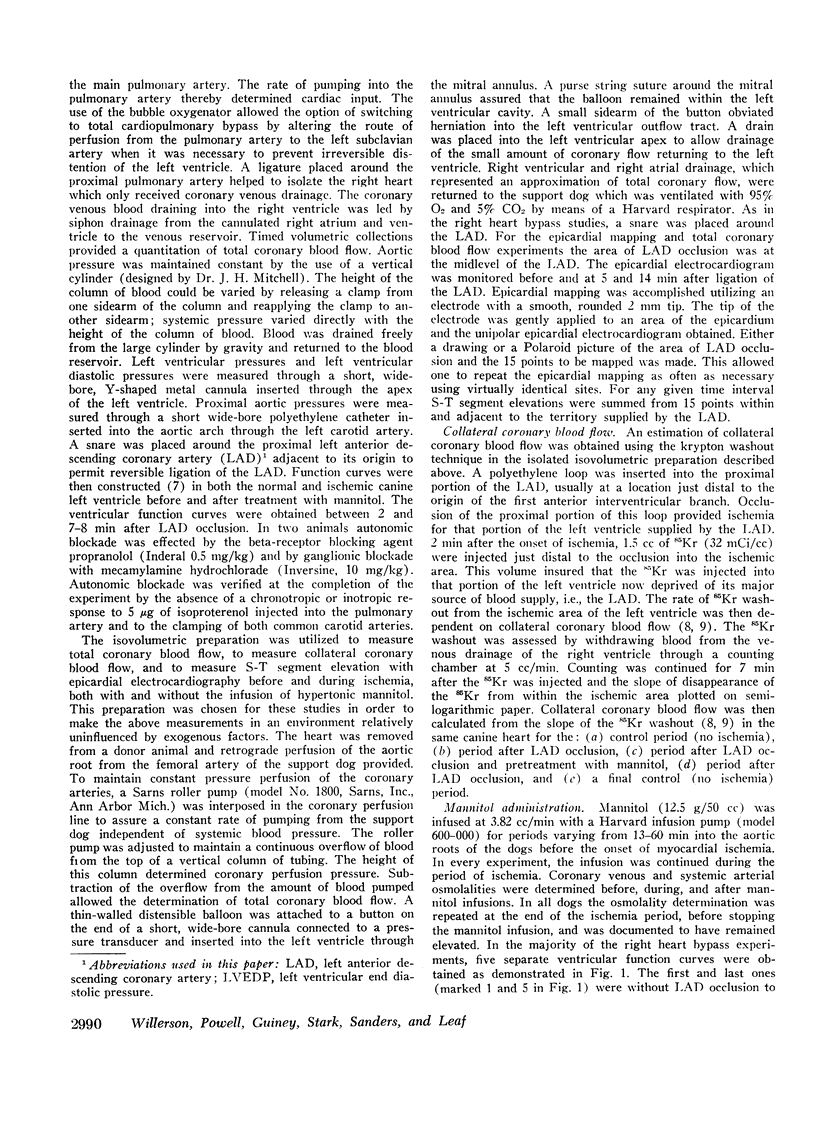

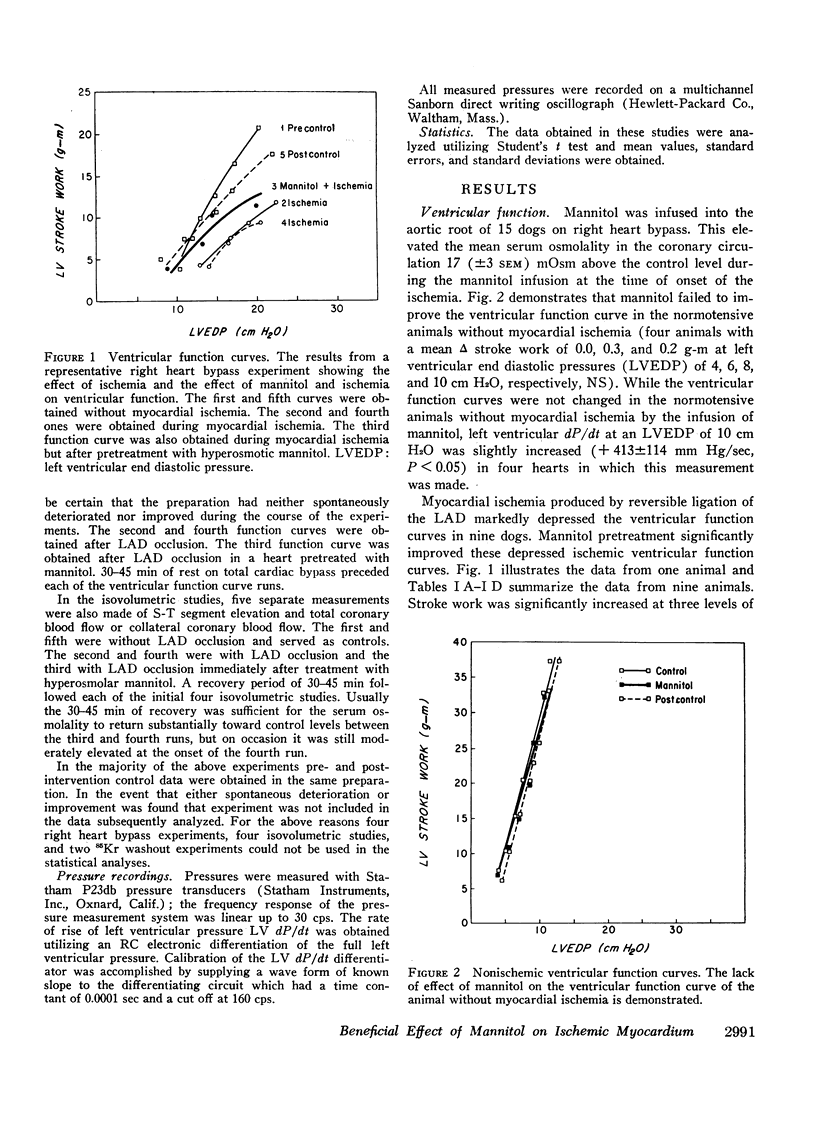

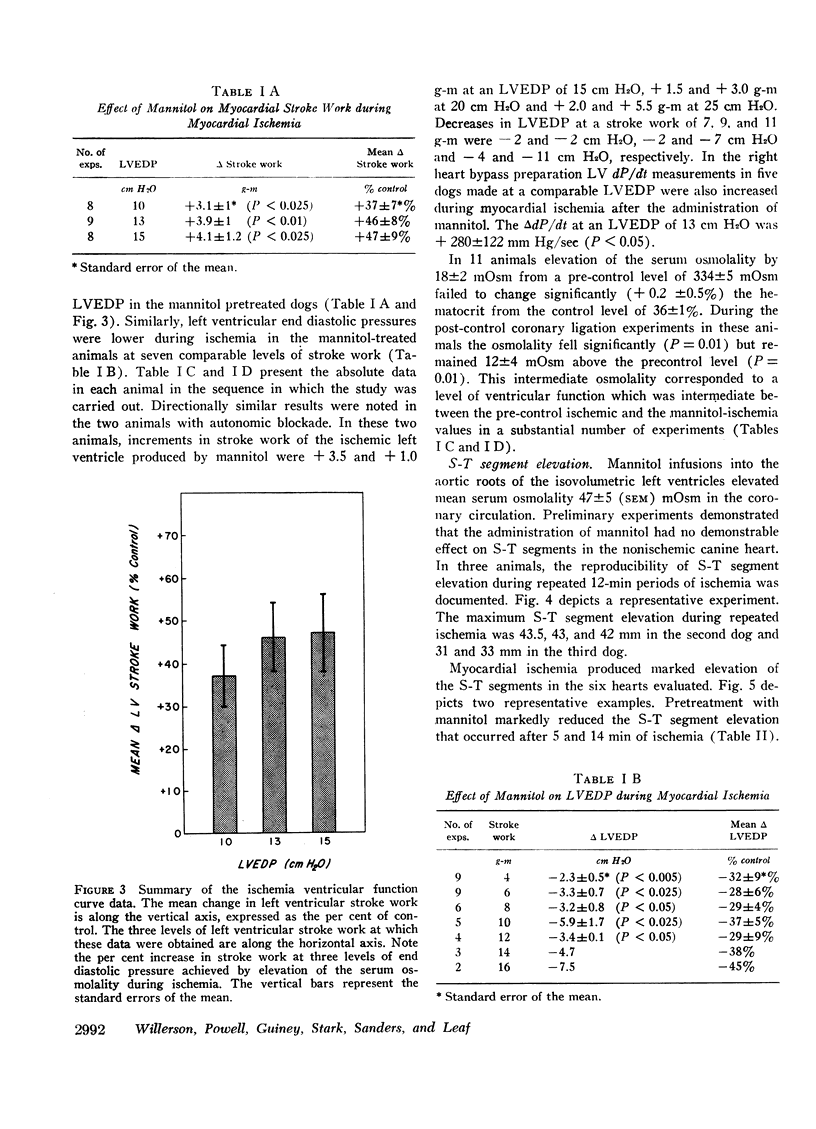

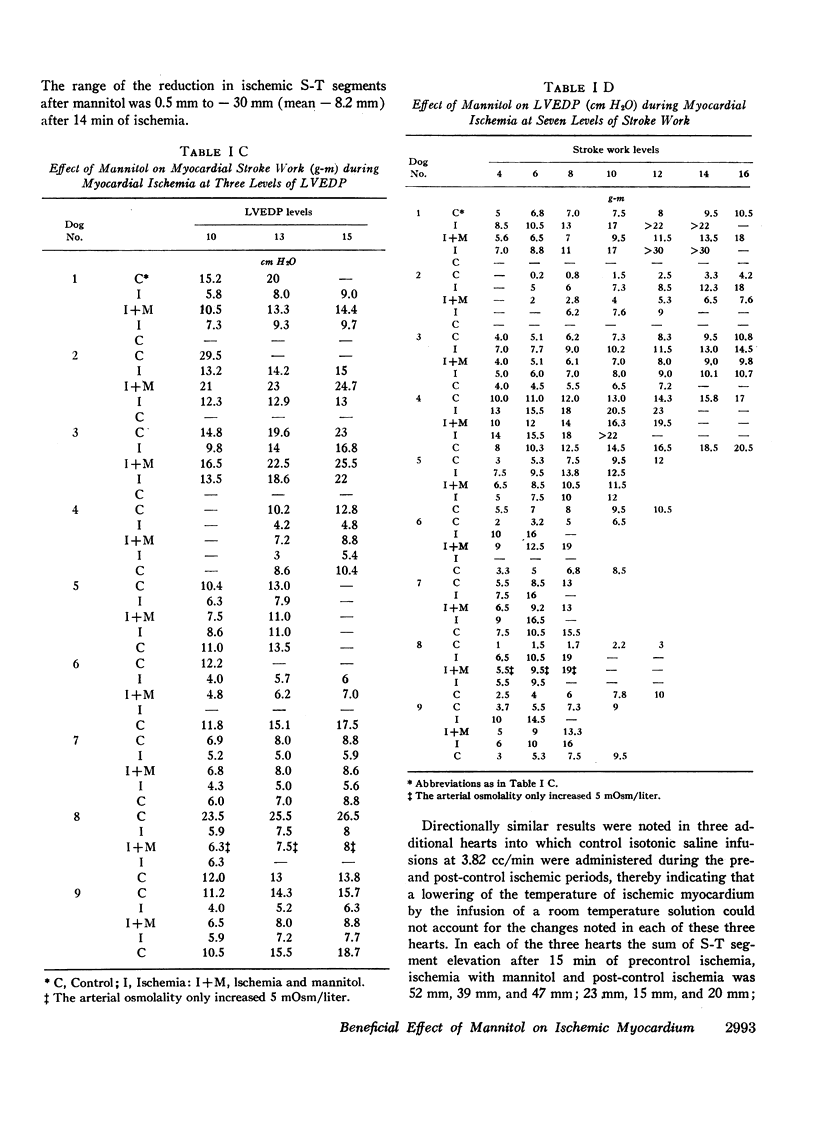

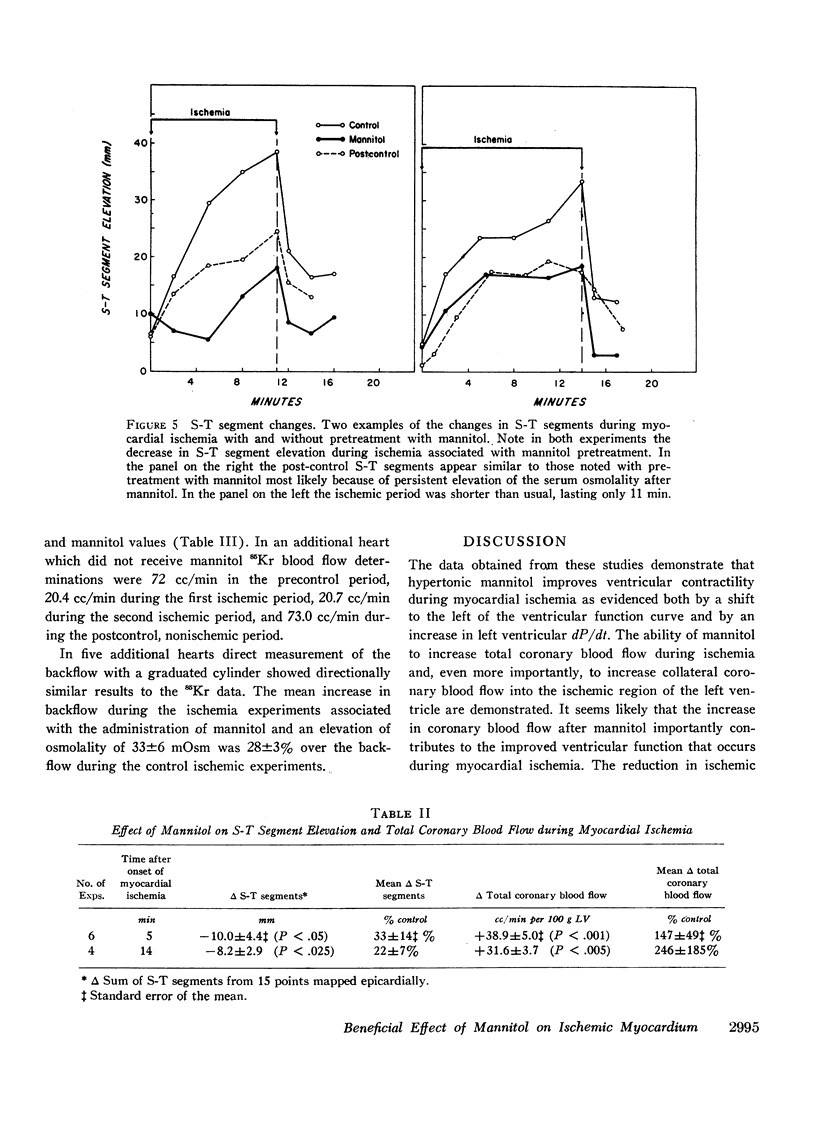

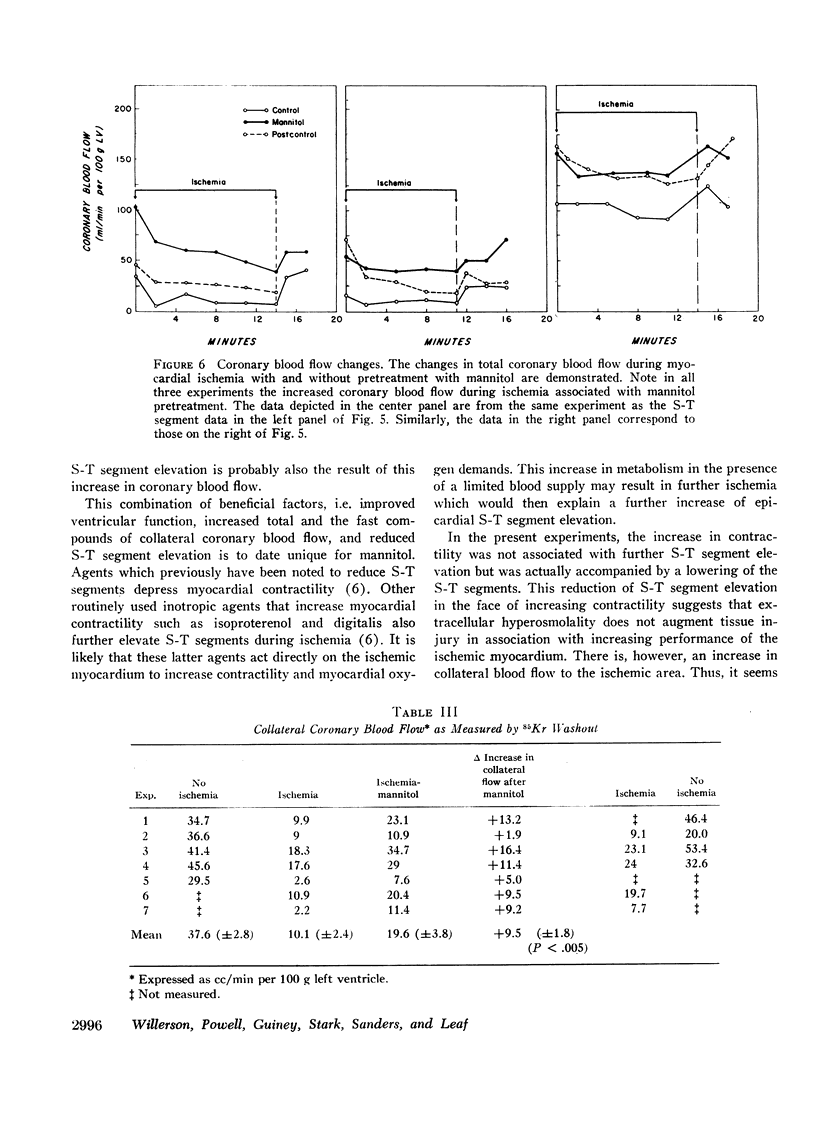

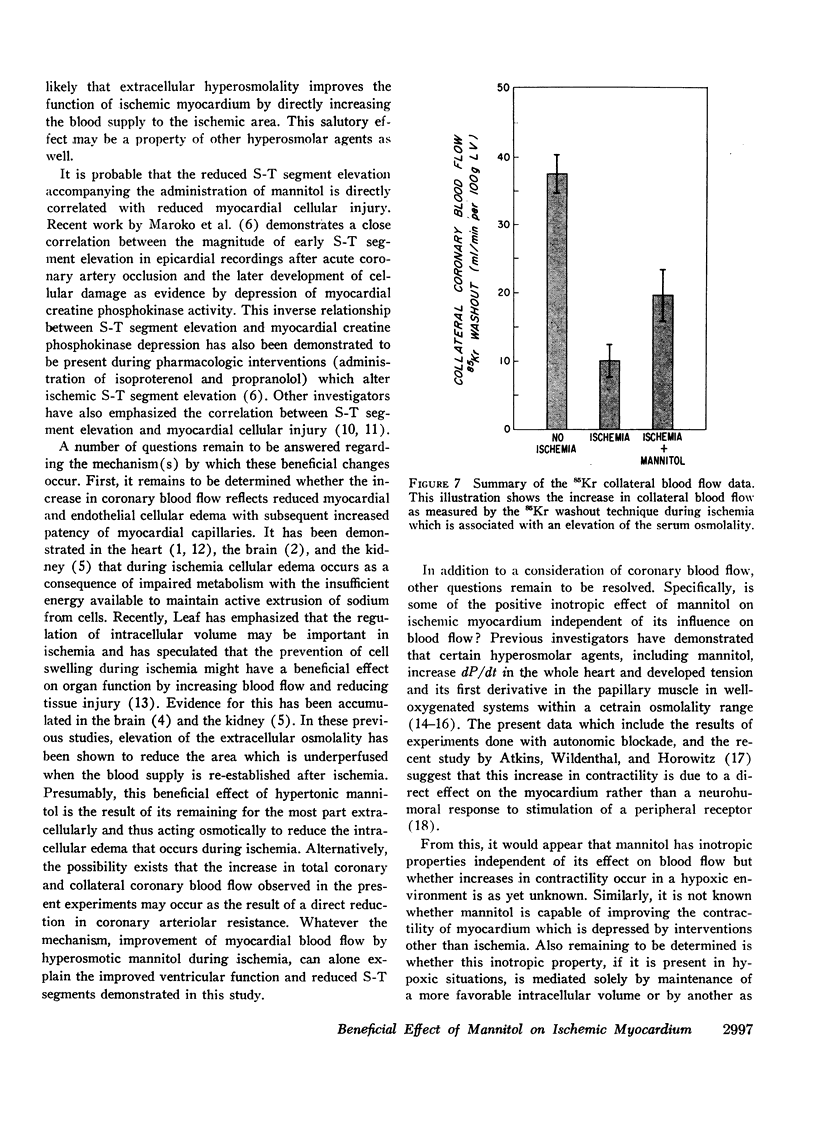

Mannitol significantly improved the depressed ventricular function curves which occurred with left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion. Mannitol also significantly lessened the S-T segment elevation (epicardial electrocardiogram) occurring during myocardial ischemia in the isovolumic hearts and this reduction was associated with significant increases in total coronary blood flow (P < 0.005) and with increased collateral coronary blood flow to the ischemia area (P < 0.005).

Thus, increases in serum osmolality produced by mannitol result in the following beneficial changes during myocardial ischemia: (a) improved myocardial function, (b) reduced S-T segment elevation, (c) increased total coronary blood flow, and (d) increased collateral coronary blood flow.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ames A., 3rd, Wright R. L., Kowada M., Thurston J. M., Majno G. Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon. Am J Pathol. 1968 Feb;52(2):437–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantu R. C., Ames A., 3rd Experimental prevention of cerebral vasculature obstruction produced by ischemia. J Neurosurg. 1969 Jan;30(1):50–54. doi: 10.3171/jns.1969.30.1.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimoskey J. E., Szentivanyi M., Zakheim R., Barger A. C. Temporary coronary occlusion in conscious dogs: collateral flow and electrocardiogram. Am J Physiol. 1967 May;212(5):1025–1032. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.212.5.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans V. J., Buja L. M., Levitsky S., Roberts W. C. Effects of hyperosmotic perfusate on ultrastructure and function of the isolated canine heart. Lab Invest. 1971 Apr;24(4):265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J., DiBona D. R., Beck C. H., Leaf A. The role of cell swelling in ischemic renal damage and the protective effect of hypertonic solute. J Clin Invest. 1972 Jan;51(1):118–126. doi: 10.1172/JCI106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERD J. A., HOLLENBERG M., THORBURN G. D., KOPALD H. H., BARGER A. C. Myocardial blood flow determined with krypton 85 in unanesthetized dogs. Am J Physiol. 1962 Jul;203:122–124. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1962.203.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENNINGS R. B., SOMMERS H. M., KALTENBACH J. P., WEST J. J. ELECTROLYTE ALTERATIONS IN ACUTE MYOCARDIAL ISCHEMIC INJURY. Circ Res. 1964 Mar;14:260–269. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOCH-WESER J. Influence of osmolarity of perfusate on contractility of mammalian myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1963 Jun;204:957–962. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1963.204.6.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASSER R. P., SCHOENFELD M. R., ALLEN D. F., FRIEDBERG C. K. Reflex circulatory effects elicited by hypertonic and hypotonic solutions injected into femoral and brachial arteries of dogs. Circ Res. 1960 Sep;8:913–919. doi: 10.1161/01.res.8.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf A. Regulation of intracellular fluid volume and disease. Am J Med. 1970 Sep;49(3):291–295. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(70)80019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Kjekshus J. K., Sobel B. E., Watanabe T., Covell J. W., Ross J., Jr, Braunwald E. Factors influencing infarct size following experimental coronary artery occlusions. Circulation. 1971 Jan;43(1):67–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAYEN J. J., SHELDON W. F., PEIRCE G., KUO P. T. Polarographic oxygen, the epicardial electrocardiogram and muscle contraction in experimental acute regional ischemia of the left ventricle. Circ Res. 1958 Nov;6(6):779–798. doi: 10.1161/01.res.6.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEEHAN H. L., DAVIS J. C. Renal ischaemia with failed reflow. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1959 Jul;78:105–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenthal K., Mierzwiak D. S., Mitchell J. H. Acute effects of increased serum osmolality on left ventricular performance. Am J Physiol. 1969 Apr;216(4):898–904. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.4.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenthal K., Skelton C. L., Coleman H. N., 3rd Cardiac muscle mechanics in hyperosmotic solutions. Am J Physiol. 1969 Jul;217(1):302–306. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.217.1.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]