Abstract

In a sample (n = 235) of 30-, 42-, and 54-month-olds, the relations among parenting, effortful control (EC), impulsivity, and children’s committed compliance were examined. Parenting was assessed with mothers’ observed sensitivity and warmth; EC was measured by mothers’ and caregivers’ reports, as well as a behavioral task; impulsivity was assessed by mothers’ and caregivers’ reports; and committed compliance was observed during a cleanup and prohibition task, as well as measured by adults’ reports. Using path modeling, there was evidence that 30-month parenting predicted high EC and low impulsivity a year later when the stability of the outcomes was controlled, and there was evidence that 30- and 42-month EC, but not impulsivity, predicted higher committed compliance a year later, controlling for earlier levels of the outcomes. Moreover, 42-month EC predicted low impulsivity a year later. Fixed effects models, which are not biased by omitted time-invariant variables, also were conducted and showed that 30-month parenting still predicted EC a year later, and 42-month EC predicted later low impulsivity. Findings are discussed in terms of the importance of differentiating between effortful control and impulsivity and the potential mediating role of EC in the relations between parenting and children’s committed compliance.

Keywords: committed compliance, effortful control, regulation, impulsivity, maternal responsiveness

The ability to comply with requests is considered an important milestone in early development, with toddlers first exhibiting the ability to comply between 12 and 18 months (Kopp, 1982). Toddlers’ compliance and noncompliance have been recognized as central in the development of internalization/conscience and problem behaviors (Keenan, Shaw, Delliquadri, Giovannelli, & Walsh, 1998; Kochanska & Aksan, 1995). Given the relevance of children’s compliance to later social behavior, researchers need to better understand the factors that predict their compliance. Thus, the goal of the present study was to examine whether two types of children’s regulation/control (i.e., effortful control, reactive control) differentially predict children’s compliance, as well as the association of maternal behaviors to children’s compliance and regulation/control over the course of the preschool years.

Two forms of compliance have been identified: committed and situational. Committed compliance refers to compliance that is internally motivated, reflected in the child’s eagerness to accept an adult’s agenda throughout a task. On the other hand, situational compliance reflects an externally motivated type of cooperation, in which the child lacks interest in the task and needs frequent prompting to comply: parent-monitored obedience (Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2001). Because committed compliance, but not situational compliance, has been found to be an early indicator of conscience development (Kochanska, Aksan, & Koenig, 1995; Kochanska et al., 2001; Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim, & Yoon, 2010; Laible & Thompson, 2000), in the current study, we focus on prediction of the former type of compliance in young children.

To understand what accounts for individual differences in committed compliance, researchers have pointed to two sets of influences: temperamental qualities of the child and qualities of the parent–child relationship. However, a more informed understanding of children’s adjustment can be obtained by considering both types of variables. In the current work, we sought to examine the mediational role of temperamental qualities of effortful and reactive control in the relation between parenting and self-regulated committed compliance in a sample of children at 30, 42, and 54 months of age.

Effortful Control (EC)

Children’s abilities to control their emotions and behavior are considered critical for successful social functioning, and these regulatory abilities are viewed as temperamentally based (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Viewed as an aspect of regulation, EC is defined as “the efficiency of executive attention, including the ability to inhibit a dominant response and/or to activate a subdominant response, to plan, and to detect errors” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 129). EC includes the abilities to voluntarily or willfully focus and shift attention and to inhibit or initiate behaviors. It develops somewhat in the first and second year of life (Diamond, 1990; Putnam & Stifter, 2002) and then improves greatly in the third year of life (Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000; Posner & Rothbart, 2007; Rueda et al., 2004). In addition, individual differences in EC have been found to be relatively stable in the early years (Kochanska et al., 2000).

Much attention has been given to the role of EC as a predictor of children’s social behavior. For example, EC has been associated with low levels of behavior problems (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Stifter, Putnam, & Jahromi, 2008; see Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010, for a review) and high levels of social adjustment (Eisenberg, Valiente, Fabes, et al., 2003; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Spinrad et al., 2007). Toddlers high in EC have been found to exhibit high levels of committed compliance, both concurrently and longitudinally (Kochanska, Murray, & Coy, 1997; Kochanska et al., 2001), and longitudinal prediction from attention and attention regulation (components of EC) to committed compliance has been found from infancy (Hill & Braungart-Rieker, 2002; Kochanska, Tjebkes, & Forman, 1998). Similarly, Stifter, Spinrad, and Braungart-Rieker (1999) found that infants who had difficulty regulating their frustration were more noncompliant as toddlers.

There is much less work examining the relations of EC to children’s committed compliance in the preschool years, particularly longitudinal work. As an exception, the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (1998) found that mother-rated temperament at 6 months of age (a composite reflecting difficult temperament) was unrelated to children’s compliance at 3 years of age. Given that EC develops later in infancy, it is likely that mothers’ reports of difficult temperament reflected individual differences in negative emotionality rather than regulatory skills. Moreover, the inclusion of other variables such as concurrent child care quality and maternal sensitivity may have resulted in an underestimate of the impact of infant temperament on children’s later compliance. Thus, it is important to examine children’s EC measured in toddlerhood (by multiple measures/reporters) to preschool children’s compliance over time.

Reactive Control (RC)

Whereas EC is seen as reflecting voluntary behavior, RC refers to aspects of functioning such as impulsivity and behavioral inhibition that are more difficult to control voluntarily (Eisenberg, Smith, Sadovsky, & Spinrad, 2004; Eisenberg & Spinrad, 2004). Studies of temperament support the notion that EC and RC are separate but related constructs (Eisenberg et al., 2004; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). Moreover, studies on the neurological bases of EC and RC support their differentiation. That is, EC is thought to be centered in the anterior cingulated gyrus and areas of the prefrontal cortex. On the other hand, the approach/avoidance tendencies involved in RC are thought to be based primarily in subcortical systems in the brain (Posner & Rothbart, 2007).

One aspect of RC, impulsivity, refers to the speed of initiating responses (e.g., rushing into new situations). Impulsive children seem to be “pulled” toward situations without thinking (Block & Block, 1980; Eisenberg, 2002). Impulsivity and EC are consistently negatively related (Eisenberg et al., 2004; Valiente et al., 2003), and children’s impulsivity is often seen as undermining children’s development. Indeed, impulsivity has been positively related to adjustment problems (e.g., Eisenberg, Valiente, et al., 2009) and negatively related to popularity (Spinrad et al., 2006). On the other hand, very low impulsivity has been associated with high behavioral inhibition, social withdrawal and internalizing problems (Eisenberg, Eggum, Sallquist, & Edwards, 2010). Because impulsive children may have difficulty regulating their behavior, we expect impulsivity to be related to lower committed compliance. It is important to note, however, that few researchers have considered both EC and impulsivity when predicting young children’s committed compliance, and it is not clear if EC and impulsivity provide some unique prediction of this outcome. Impulsivity may be inversely correlated with committed compliance at a young age due to the effects of EC in modulating impulsive tendencies (Eisenberg et al., 2004). The unique effects of EC (controlling for the effects of parenting and impulsivity) have not been tested, and most studies to date have not used multiple reporters/methods to examine these relations.

The Relations of Maternal Behavior to Children’s EC and Social Functioning

Although children’s EC is clearly a strong predictor in the development of social competence and problem behaviors, parenting also has received considerable attention as a predictor of children’s social behavior (Blandon, Calkins, & Keane, 2010; Campbell, Spieker, Vandergrft, Belsky, & Burchinal, 2010; Kochanska, Barry, Aksan, & Boldt, 2008). The prevailing view is that children who have warm and sensitive parents will be eager to embrace their parents’ goals and rules. Indeed, parental responsivity has been associated with higher levels of compliance in children (Braungart-Rieker, Garwood, & Stifter, 1997; Crockenberg & Litman, 1990; Kochanska et al., 2008; Kochanska, Woodward, et al., 2010), and mother– child attachment security (promoted by maternal responsivity) has been related to later cooperation in young children (Kochanska, Aksan, & Carlson, 2005; Matas, Arend, & Sroufe, 1978). Developmental scientists have increasingly been aware, however, that researchers must move beyond studying main effects to examine the processes underlying relations. What is less known are the mechanisms though which parenting predicts children’s developmental outcomes such as committed compliance. In particular, EC might mediate the relation between parenting and compliance, and this process has not been examined in prior work.

In general, warm and supportive parenting is thought to facilitate EC by maintaining optimal levels of arousal and creating an environment in which the child learns the give-and-take basis of social relationships (Feldman & Klein, 2003). Parents may foster EC though modeling effective ways of dealing with emotions and behaviors, responding to emotions in supportive ways, and the development of a secure parent– child attachment relationship (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). Indeed, researchers have demonstrated that supportive parental behaviors relate positively to children’s EC (Belsky, Pasco Fearon, & Bell, 2007; Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002; Spinrad et al., 2007; Valiente et al., 2006). However, little work has addressed the relation of parenting to children’s EC over time after controlling for stability in EC, especially in the preschool years (see Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2010). It may be that parenting is particularly important when children’s EC is still relatively immature (Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2010).

Eisenberg et al. (1998) proposed that some of the relations between parenting and children’s social outcomes are mediated through children’s regulation. Some support for this mediated relation has been found in work with older children (Belsky, Pasco Fearon, & Bell, 2007; Cunningham, Kliewer, & Garner, 2009; Hastings et al., 2008; Kim & Brody, 2005; Valiente et al., 2006; Yap, Allen, & Ladouceur, 2008). Using the current longitudinal sample, Spinrad et al. (2007) found toddlers’ EC concurrently mediated the relations between parental supportive practices and low levels of toddlers’ externalizing problems and separation distress and high levels of social competence at 18 and 30 months of age. In addition, a positive association was found between maternal supportiveness and EC across time, even when controlling for earlier levels of EC (although earlier EC did not predict later outcomes once stability in the outcomes was controlled). In a three-time-point model (at 18, 30, and 42-months of age), there was no evidence consistent with causal relations between EC and children’s problem behaviors over time once stability of the outcomes was taken into account, although there was some evidence of a continuing (and apparently additional) association within time even when stability was taken into account (Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2010).

Two studies are particularly relevant to the current investigation. First, Kochanska and Knaack (2003) found that EC mediated the relations between power assertion and lower conscience development. This study is pertinent to the current work because child compliance is thought to be a first marker of internalization (Kochanska, 1995, 1997). However, it is also important to note that these investigators assessed power assertion and EC at the same time; thus, longitudinal work on the potential meditational processes is needed. In the second study, Volling, McElwain, Notaro, and Herrera (2002) found evidence that early effortful attention at 12 months mediated the relations between maternal emotional availability at 12 months and situational (noninternalized) compliance at 16 months. The fact that situational, and not committed, compliance was predicted may have been due to the young age of the toddlers studied. Perhaps, as children’s ability to wholeheartedly comply with adults’ standards develops, this relation is more evident.

It is also important to consider the notion that children’s EC and committed compliance may evoke more positive behaviors from socializers than do noncompliant behaviors. That is, when children obey their mothers’ commands, and do so in an internalized manner, mothers may be relatively willing to interact with their children in sensitive ways and provide positive interactions in the future. On the other hand, children’s unregulated or defiant behaviors may elicit more harsh interactions and conflict from mothers. Thus, it is possible that bidirectional relations among the constructs predict children’s development.

The Current Study

In the present study, we sought to examine the relations of parenting, EC, impulsivity, and committed compliance from 2.5 to 4.5 years of age using path modeling. Our first goal was to examine whether EC mediated the relations between parenting and young children’s committed compliance. An ideal test of mediation involves studying a minimum of three times. Stability of the outcome is taken into account, as are relations among predictors and committed compliance within time and tests of mediating paths are conducted (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). In the present study, we used three assessments to examine the hypothesis that parenting behaviors (i.e., sensitivity, warmth) predicted young children’s EC or impulsivity, which, in turn, predicted future committed compliance. Because early committed compliance has been viewed as a first step toward the process of internalization in young children (Kochanska, 2002; Kochanska et al., 1995; Laible & Thompson, 2000) and predicts moral reasoning and conduct (Groenendyk & Volling, 2007; Kochanska et al., 1995, 2001), a major goal of the current study was to understand the factors that may contribute to children’s committed compliance over time.

Second, although researchers have differentiated between EC and RC, there has been very little work in which the differential effects of EC and RC have been tested in relation to children’s positive social functioning (see Spinrad et al., 2006, for exception), particularly in work with young children. Our goal was to examine unique relations of parenting, EC, and impulsivity with committed compliance. An additional goal was to identify any bidirectional processes among the constructs over time. Thus, we also tested whether low EC and committed compliance predicted less supportive parenting over time.

Finally, because of the longitudinal nature of the study, it was important to reduce bias from potential time-invariant omitted variables that were not measured in the current study. To meet this goal, a fixed-effects analysis also was conducted to determine if results from the earlier models remained after controlling for potential time-invariant variables. Changing results may indicate that findings are due to potential omitted variables and should be treated with caution.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited at birth from three local hospitals in a large metropolitan area in the Southwest United States (Spinrad et al., 2007). Laboratory visits were conducted when the child was approximately 18, 30, 42, and 54 months of age (henceforth labeled T1, T2, T3, and T4). For the current investigation, data from T2, T3, and T4 were used because committed compliance at the youngest age (18 months) was relatively infrequent compared with later ages. Moreover, EC becomes increasingly stable and more organized after age 2 (Kochanska et al., 2000).

The initial visit (T1) involved 256 children and their mothers. At T2, 230 toddlers and their mothers participated (including 14 families who participated only by mail; 128 boys, 102 girls; ages 27.2–32.0 months, M = 29.8 months, SD = 0.65). At T3, 210 children participated in the study (117 boys, 93 girls; ages 39.17–44.20 months, M = 41.75 months, SD = 0.65), including 18 who participated by mail. At T4, 192 children participated in the study (107 boys, 84 girls; 52.97–57.20 months, M = 53.89 months, SD = 0.80), including 24 participating by mail.

In terms of ethnicity, at T2, 77% of children were non-Hispanic, and 23% were Hispanic (with 22% Hispanic at T3 and 21% at T4). In addition, in terms of race, 84% of children were Caucasian, although African Americans (6%), Native Americans (5%), and Asians (3%) were also represented (approximately 1% identified themselves as “more than one race,” “other” or “unknown”). The race estimates were similar at T3 and T4, with 83% Caucasian, 6% African American, 6% Native American, 2% Asian at T3 and T4. Annual family income ranged from less than $15,000 to over $100,000, with the average income at the level of $45,000 –$60,000. Parents’ education ranged from eighth grade to the graduate level; the average number of years of formal education completed by both mothers and fathers was approximately 14 years (2 years of college). At T2, 59% of all mothers were employed (80% of these full-time), at T3, 60.5% of the mothers were employed (78% of these full-time), and at T4, 66.1% of the mothers were employed (80% of these full-time). Eighty-one percent of the parents were married and had been married from less than 1 year to 26 years (M = 6.9 years, SD = 3.9). Seventy-one percent of the children had siblings by T2, and 44% were first-borns.

The individuals who participated at T1 and continued the study (n = 185) were compared with those who were lost because of attrition by the last assessment at 54 months (n = 71). In terms of demographic variables, families that were lost because of attrition were marginally lower on family income (M = 3.70; 3 = between 30 and 45K; 4 = 45 to 60K) and significantly lower on mothers’ education (M = 4.03; 3 = high school graduate; 4 = some college) than those who remained in the study (M = 4.21 and 4.37), ts(226, 238) = 1.93 and 2.17, ps < .06 and .04, respectively. Attrition analyses also were conducted to determine if there were differences in demographic and study variables at the first assessment between the individuals who participated at only one or two assessments used in the current article (n = 53) versus those that had data at all three time points (n = 187). Children who had incomplete data were older at the T2 lab visit (M = 29.98 months) and higher on T2 caregiver reports’ of EC (M = 5.04) and had mothers who were rated lower on T2 observed warmth during the puzzle task (M = 3.37), compared with those had complete data (Ms = 29.72, 4.63, and 3.53), ts (214, 150, 214) = −2.33, −2.67, and 2.14, ps < .05, .01, and .05, for age, caregiver-rated EC, and maternal warmth, respectively.

Procedures

At each assessment, mothers were sent a packet of questionnaires by mail to complete and to bring to the laboratory visit. Laboratory sessions lasted approximately 1.5–2 hr. As part of a series of tasks, mothers were observed interacting with their child during both free-play and challenging puzzle tasks. Young children’s EC was assessed during a task that involved waiting for a prize. The children also were observed during two compliance tasks, including a cleanup task (“do task”) and a prohibited toys task (“don’t task”). All tasks were videotaped for later coding. Mothers completed additional questionnaires in the laboratory. At the end of the session, the participants were paid, and mothers were asked to give permission for questionnaires to be sent to the child’s nonparental caregiver/teacher (or another nonparental adult who knew the child well). Caregiver questionnaire packets were sent and returned through the mail. At T2, T3, and T4, 152, 151, and 145 caregivers, respectively, returned questionnaires (23, 26, and 19 did not have a caregiver, respectively).

Measures

Maternal observed sensitivity and warmth

Maternal sensitivity was assessed during two mother– child interactions in the laboratory. First, a free-play interaction was observed in which mothers were presented with a basket of toys and asked to play as they normally would for 3 min. Second, a teaching paradigm was used in which mothers and children were presented with a difficult puzzle (pegs/geometric shapes at T2, a Lego model at T3, and a puzzle-box task at T4 containing a numbers puzzle using a contraption in which the child was asked to put their hand through sleeves attached to a box and complete the puzzle without looking while the mother provided instructions). Mothers were instructed to “teach their child to complete the puzzle” and were given 3 min to complete the task (4 min at T4). Mothers were rated for sensitivity on a 4-point scale every 15 s for the free-play and every 30 s for the puzzle task (Fish, Stifter, & Belsky, 1991). Maternal sensitivity to the child was based on behavioral evidence of being appropriately attentive to the child as well as appropriately and contingently responsive to his or her affect, interests, and abilities (1 = no evidence of sensitivity, 2 = minimal sensitivity, 3 = moderate sensitivity—more than one instance or one prolonged instance, clear evidence that mother is more than minimally tuned into child, 4 = mother was very aware of the child, contingently responsive to his or her interests and affect and had an appropriate level of response/stimulation). Essentially, a sensitive mother follows her child’s signals, rather than imposing her own agenda on him or her. Inter-rater reliabilities (ICCs) were assessed for approximately 25% of the sample and were .86, .68, and .69 for the free-play at T2, T3, and T4 and .71, .83, and .61 for the puzzle task at T2, T3, and T4, respectively. Maternal sensitivity was positively correlated between the two tasks at each age, rs(214, 190, 164) = .27, .29, and .32, ps < .01 at T2, T3, and T4, respectively. Thus, to reduce the number of indicators (so that the number of estimated parameters given our sample size would be reduced) and to increase the reliability of the construct, a composite of maternal sensitivity was created by averaging the scores across the free-play and puzzle tasks within each assessment.

In addition, we coded maternal warmth during the teaching task (scored every 30 s) based on mothers’ levels of friendliness, displays of closeness, physical affection, encouragement and positive affect with the child, and the quality of the mothers’ tone/conversation (1 = no evidence of warmth—the parent ignores the child, is not friendly or positive, 2 = minimal warmth—the parent displays little positive affect, does not initiate contact, and not friendly or close to the child, 3 = moderate warmth—a little positive affect and slight display of friendliness, 4 = engaged with the child for much of the time and touched the child in a positive way, 5 = very engaged with the child, positive affect was predominant, and the mother was physically affectionate). Inter-rater reliabilities (ICCs for approximately 25% of the sample were .66, .88, and .79 at T2, T3, and T4, respectively).

Effortful control (EC)

EC was assessed with the Early Childhood Behavioral Questionnaire (ECBQ; Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, 2006) at T2 and the Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994) at T3 and T4. Mothers and nonparental caregivers rated EC using the attention focusing, attention shifting, and inhibitory control subscales (1 = never; 7 = always). The attentional focusing subscales consisted of 12 items (ECBQ) or 14 items (CBQ) assessing children’s ability to concentrate on a task (e.g., “When playing alone, how often did your child play with a set of objects for 5 min or longer at a time?” [ECBQ], “Sometimes becomes absorbed in a picture book and looks at it for a long time” [CBQ]; αs = .81 and .85 at T2, .77 and .74 at T3, and .77 and .72 at T4, for mothers and caregivers, respectively). The attention shifting subscales assessed children’s ability to move attention from one activity to another (12 items for both the ECBQ and CBQ; e.g., “During everyday activities, how often did your child seem able to easily shift attention from one activity to another?” αs = .73 and .71 at T2, .67 and .80 at T3, and .73 and .82 at T4 for mothers and caregivers, respectively). The inhibitory control subscale included 12 items (ECBQ) or 13 items (CBQ) used to assess children’s ability to control their behavior (e.g., “When told ‘no’, how often did your child stop an activity quickly?” αs = .88 and .88 at T2, .77 and .82 at T3, and .80 and .83 at T4 for mothers and caregivers, respectively). For both mothers and caregivers, composite scores for children’s EC were created by averaging the subscale scores of attention shifting, attention focusing, and inhibitory control, for mothers and caregivers, respectively, at T2, rs(218 –221) = .30 to .36, ps < .01, and rs(141–143) = .45 to .53, ps < .01; at T3, rs(203) = .23 to .51, ps < .01 and rs(147–148) = .41 to .68, ps < .01; and at T4, rs(186) = .21 to .56, ps < .01 and rs(143–144) = .39 to .64, ps < .01. To reduce the number of variables for analyses and because aggregation of reporters/measures increases reliability (Rushton, Brainerd, & Pressley, 1983), we created a larger composite averaging the two reporters (when available) to create an adult-report composite, rs(146, 145, 143) = .18, .25, and .31 between reporters (ps < .03, .01, and .01 for T2, T3, and T4, respectively).

Children also participated in a delay task at each age (Kochanska et al., 2001; Kochanska et al., 2000). At each age, children were presented with an attractive gift bag and told that there was a prize in the bag. The child was left alone in the room and told not to touch or open the gift until the experimenter returned with a bow (2 min). The gift was placed on a table directly in front of the child. Children’s level of restraint was coded on a 5-point scale (1 = child pulls box from bag, 2 = child puts hand into bag, 3 = child peeks in bag, 4 = child touches bag but does not peek, 5 = child does not touch bag). Inter-rater reliabilities (kappas) computed on 25% of the sample were .86, .86, and .96, for T2, T3, and T4, respectively.

Impulsivity

Impulsivity was assessed at each age using the activity/impulsivity subscale of the Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003). This scale consisted of six items relating to the child’s activity level (e.g., “is constantly moving”) and impulsivity (e.g., “gets hurt so often you can’t take your eyes off him or her”). Items were rated on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat/sometimes true, 2 = very true/often), αs = .72 and .75 at T2, .69 and .69 at T3, and .71 and .72 at T4, for mothers and caregivers, respectively.

Children’s committed compliance

Committed compliance was observed during two contexts (“do” and “don’t”; see Kochanska et al., 2001). In the “do” context, the mother was instructed to ask the child to cleanup toys and put them in a large basket. Prior to the cleanup task, the mother and child were provided a number of toys that were spilled on the floor. The cleanup task lasted for 3-min. In the “don’t” context, children were presented with a shelf of attractive toys. Mothers were told to prohibit the child from playing with the toys, and the shelf also displayed a “do not touch” sign to remind the mothers of the rule.

Committed compliance was defined as the instances when the child eagerly complied with requests. For the cleanup task, committed compliance was coded (present/absent) during 30-s intervals if the child picked up the toys and put them in the basket without a great deal of parental control (see Kochanska & Aksan, 1995; Kochanska et al., 2001). For the prohibition task, coders first identified every instance in which the child paid attention to the prohibited toys, and the child’s responses were coded until the child was no longer interested in the toys. Committed compliance in this task was coded if the child looked at the toys but made no attempt to touch the toys or pointed to the toys and said, “no, no.” Inter-rater reliabilities (kappas) were calculated on approximately 25% of the data and were .96, .62, and .98 for the cleanup task and .75, .77, and .66 for the prohibition task at T2, T3, and T4, respectively.

To increase reliability (and number of incidents) of the observed measures of committed compliance and to reduce the number of indicators in the models, we combined (averaged) the child’s observed ratings of committed compliance across the cleanup and prohibition tasks, rs(201, 169, 106) = .13, .25, and .00, ps < .07, .01, and .98 for T2, T3, and T4, respectively. Although committed compliance was unrelated across the cleanup and prohibition tasks at T4, we chose to combine the two tasks to maintain similar indicators across time. In addition, similar to work of Kochanska et al. (2001), there was relatively little variability in committed compliance to the prohibition task at T4 (a ceiling effect); thus, combining the two tasks also served to increase the variability in committed compliance at that age.

Mothers and teachers/caregivers also reported on children’s compliance using the compliance subscale of the ITSEA (Carter et al., 2003). This subscale included eight items assessing the child’s compliant behavior and ability to follow rules (e.g., “puts toys away after playing”), αs = .64 and .74 for T2, .72 and .80 for T3, and .75 and .77 for T4. To reduce the number of variables for analyses and because aggregation of reporters/measures increases reliability (Rushton et al., 1983), we created a larger composite averaging the two reporters (when available) to create an adult-report composite of compliance, rs(146, 142, 139) = .34, .32, and .34 between reporters, ps < .01 for T2, T3, and T4, respectively.

Results

Descriptive Analyses: Relations with Sex and Socioeconomic Status

Means and standard deviations of the study variables are presented in Table 1. In terms of sex differences, at T2, mothers were more sensitive toward their daughters than sons, mothers rated their girls as higher in EC than boys, and girls displayed more EC in the delay task than did boys. At T2 and T3, girls displayed more committed compliance than did boys.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables at T2, T3, and T4

| Variable | Time 2

|

Time 3

|

Time 4

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total

|

Male

|

Female

|

Total

|

Male

|

Female

|

Total

|

Male

|

Female

|

||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| O sens | 3.30a | 0.36 | 3.25 | 0.37 | 3.37 | 0.32 | 3.09 | 0.42 | 3.06 | 0.43 | 3.13 | 0.40 | 3.58 | 0.31 | 3.56 | 0.33 | 3.61 | 0.28 |

| O warm | 3.50 | 0.47 | 3.47 | 0.47 | 3.55 | 0.46 | 2.96 | 0.33 | 2.96 | 0.31 | 2.95 | 0.35 | 3.24 | 0.40 | 3.20 | 0.38 | 3.30 | 0.42 |

| M EC | 4.38b | 0.58 | 4.29 | 0.58 | 4.48 | 0.58 | 4.33 | 0.54 | 4.29 | 0.55 | 4.38 | 0.52 | 4.53 | 0.56 | 4.47 | 0.57 | 4.60 | 0.54 |

| C EC | 4.70 | 0.72 | 4.71 | 0.79 | 4.70 | 0.64 | 4.59 | 0.64 | 4.52 | 0.64 | 4.67 | 0.63 | 4.63 | 0.67 | 4.60 | 0.61 | 4.67 | 0.74 |

| A EC | 4.47 | 0.55 | 4.42 | 0.57 | 4.53 | 0.52 | 4.42e | 0.50 | 4.36 | 0.49 | 4.49 | 0.51 | 4.56 | 0.53 | 4.51 | 0.52 | 4.63 | 0.53 |

| O gift | 3.14c | 1.54 | 2.92 | 1.54 | 3.42 | 1.50 | 2.85 | 1.04 | 2.73 | 1.11 | 2.99 | 0.93 | 3.48 | 0.63 | 3.43 | 0.68 | 3.54 | 0.57 |

| M impuls | 1.80 | 0.40 | 1.82 | 0.40 | 1.78 | 0.40 | 1.82 | 0.40 | 1.85 | 0.41 | 1.77 | 0.39 | 1.74 | 0.38 | 1.75 | 0.40 | 1.72 | 0.36 |

| C impuls | 1.67 | 0.43 | 1.73 | 0.46 | 1.60 | 0.38 | 1.63 | 0.42 | 1.61 | 0.44 | 1.64 | 0.39 | 1.57 | 0.41 | 1.58 | 0.40 | 1.55 | 0.44 |

| M comply | 2.30 | 0.27 | 2.29 | 0.27 | 2.31 | 0.26 | 2.41 | 0.31 | 2.40 | 0.30 | 2.43 | 0.32 | 2.48 | 0.32 | 2.45 | 0.33 | 2.52 | 0.29 |

| C comply | 2.43 | 0.34 | 2.42 | 0.36 | 2.45 | 0.31 | 2.49 | 0.36 | 2.48 | 0.39 | 2.50 | 0.33 | 2.54 | 0.37 | 2.52 | 0.34 | 2.57 | 0.39 |

| A comply | 2.34 | 0.26 | 2.33 | 0.27 | 2.35 | 0.24 | 2.44 | 0.29 | 2.43 | 0.28 | 2.45 | 0.29 | 2.50 | 0.28 | 2.48 | 0.28 | 2.53 | 0.30 |

| O comply | 0.39d | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.62f | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.30 | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 0.72 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.25 |

Note. O = observed; sens = sensitivity; warm = warmth; M = mother-reported; EC = effortful control; C = caregiver-reported; A = adult-reported composite; gift = gift-wrap task; impuls = activity/impulsivity; comply = compliance.

Sex difference, t(213) = −2.48, p < .05.

Sex difference, t(221) = −2.39, p < .05.

Sex difference, t(212) = −2.40, p < .05.

Sex difference, t(214) = −1.96, p = .05.

Sex difference, t(207) = −1.93, p < .10.

Sex difference, t(189) = −2.79, p < .01.

In addition, there were numerous relations between socioeconomic status (SES; standardized score averaging education and income) and concurrent study variables. At T2, SES was significantly correlated with mothers’ high sensitivity and warmth, children’s ability to delay on the gift task, and mothers’ reports of lower impulsivity, rs(208, 208, 206, 219) = .38, .36, .26, and −.20, ps < .01, respectively. At T3, SES was correlated with mothers’ high sensitivity and warmth, mothers’ and caregivers’ ratings of EC, children’s delay ability on the gift task, mothers’ and caregivers’ low ratings on impulsivity and caregivers’ high ratings of compliance, rs(186, 186, 203, 145, 184, 203, 145, 142) = .40, .28, .21, .23, .28, −.22, −.18, and .16 ps < .01, .01, .01, .01, .01, .01, and .05, respectively. At T4, SES was correlated with high maternal sensitivity and warmth, caregivers’ ratings of EC, children’s delay ability, caregivers’ reports of low impulsivity, mothers’ ratings of high compliance, and observed compliance, rs(160, 159, 142, 159, 142, 182, 161) = .28, .27, .19, .18, −.21, .18, and .16, ps < .01, .01, .05, .05, .05, .05, .and .05, respectively.

Correlations Among Indices of Analogous Constructs

Correlations among the constructs at each age are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Mothers’ sensitivity and warmth were positively correlated at each age. In addition, at each age, mother- and caregiver-reported activity/impulsivity were at least marginally positively correlated; observed regulation was positively correlated with adult-reported EC; and mother- and caregiver-rated compliance were positively correlated. At T2 and T4, children’s observed committed compliance was positively related to mother-reports of compliance.

Table 2.

Correlations of Study Variables Within 30 Months of Age

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. O sens | — | .49*** | .22** | .24** | .25*** | .26*** | −.28*** | −.11 | .37*** | .31*** | .37*** | .17* |

| 2. O warm | — | .19** | .14† | .20** | .19** | −.16* | −.18* | .23** | .24** | .25*** | .02 | |

| 3. M EC | — | .18* | .81*** | .16* | −.40*** | −.14† | .62*** | .24** | .52*** | .09 | ||

| 4. C EC | — | .83*** | .16* | −.12 | −.49*** | .25** | .71*** | .63*** | .10 | |||

| 5. A EC | — | .18** | −.36*** | −.44*** | .54*** | .64*** | .68*** | .12† | ||||

| 6. O gift | — | −.14* | .01 | .20** | .25** | .26*** | .27*** | |||||

| 7. M impuls | — | .20* | −.35*** | −.18* | −.33*** | −.10 | ||||||

| 8. C impuls | — | −.12 | −.50*** | −.40*** | −.08 | |||||||

| 9. M comply | — | .34*** | .84*** | .24*** | ||||||||

| 10. C comply | — | .86*** | .12 | |||||||||

| 11. A comply | — | .23** | ||||||||||

| 12. O comply | — |

Note. O = observed; sens = sensitivity; warm = warmth; M = mother-reported; EC = effortful control; C = caregiver-reported; A = adult-reported composite; gift = gift-wrap task; impuls = activity/impulsivity; comply = compliance.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Correlations of Study Variables Within 42 Months of Age

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. O sens | — | .51*** | .24** | .21* | .27*** | .36*** | −.23** | −.21* | .19* | .17* | .21** | .16* |

| 2. O warm | — | .05 | .08 | .10 | .17* | −.09 | −.12 | −.01 | .05 | .04 | .07 | |

| 3. M EC | — | .25** | .82*** | .27*** | −.52*** | −.18* | .67*** | .22** | .55*** | .13† | ||

| 4. C EC | — | .84*** | .24** | −.18* | −.64*** | .25** | .76*** | .64*** | .14† | |||

| 5. A EC | — | .34*** | −.46*** | −.54*** | .57*** | .66*** | .69*** | .14* | ||||

| 6. O gift | — | −.29*** | −.01 | .20** | .21* | .25*** | .24** | |||||

| 7. M impuls | — | .14† | −.40*** | −.22** | −.39*** | −.19* | ||||||

| 8. C impuls | — | −.14† | −.46*** | −.39*** | −.10 | |||||||

| 9. M comply | — | .32*** | .84*** | .09 | ||||||||

| 10. C comply | — | .85*** | .12 | |||||||||

| 11. A comply | — | .12 | ||||||||||

| 12. O comply | — |

Note. O = observed; sens = sensitivity; warm = warmth; M = mother-reported; EC = effortful control; C = caregiver-reported; A = adult-reported composite; gift = gift-wrap task; impuls = activity/impulsivity; comply = compliance.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 4.

Correlations of Study Variables Within 54 Months of Age

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. O sens | — | .57*** | .29*** | .15† | .27*** | .22** | −.18* | −.27** | .34*** | .22* | .32*** | .24** |

| 2. O warm | — | .19* | .17* | .21** | .10 | −.14† | −.24** | .28*** | .21* | .29*** | .13† | |

| 3. M EC | — | .31*** | .83*** | .16* | −.44*** | −.26** | .63*** | .32*** | .57*** | .12 | ||

| 4. C EC | — | .85*** | .06 | −.18* | −.57*** | .32*** | .69*** | .63*** | .16† | |||

| 5. A EC | — | .19* | −.39*** | −.53*** | .56*** | .65*** | .68*** | .18* | ||||

| 6. O gift | — | −.06 | −.06 | .16* | .01 | .14† | .26** | |||||

| 7. M impuls | — | .17* | −.28*** | −.18* | −.28*** | .04 | ||||||

| 8. C impuls | — | −.27** | −.61*** | −.54*** | −.17† | |||||||

| 9. M comply | — | .34*** | .84*** | .20** | ||||||||

| 10. C comply | — | .84*** | .14 | |||||||||

| 11. A comply | — | .21** | ||||||||||

| 12. O comply | — |

Note. O = observed; sens = sensitivity; warm = warmth; M = mother-reported; EC = effortful control; C = caregiver-reported; A = adult-reported composite; gift = gift-wrap task; impuls = activity/impulsivity; comply = compliance.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Relations of Socialization, Children’s EC, and Impulsivity to Committed Compliance

To examine relations among the study variables, we first computed zero-order correlations. Next, we tested longitudinal path models that controlled for stability in the outcomes over time (Cole & Maxwell, 2003).

Zero-order concurrent correlations

Concurrent correlations of children’s committed compliance with maternal socialization and children’s EC and impulsivity are presented in Tables 2– 4. Mothers’ and caregivers’ ratings of compliance were linked to higher maternal sensitivity (and warmth at T2 and T4), adults’ reports of EC, and observed delay ability (although only for mothers’ reports of compliance at T4). In addition, adult-reported compliance was related to lower impulsivity, particularly within reporter (mothers’ reports of compliance were unrelated to caregivers’ reports of impulsivity at T2). Observed committed compliance was positively related to mothers’ sensitivity and observed EC within all time points and was at least marginally related to adults’ reports of high EC at T3 and to caregiver-reported EC at T4.

Measurement models

Prior to computing the path models, measurement models were tested through confirmatory factor analyses, which examined whether the manifest variables related to one another in the expected manner. The models contained four latent constructs at each age (a total of 12 latent constructs): maternal sensitivity/warmth, children’s EC, children’s impulsivity, and committed compliance. For maternal strategies, maternal warmth (during puzzle) and maternal sensitivity (combined responses in free-play and puzzle) were used as indicators. The latent construct of EC included the composite of adult-reported EC and the delay score from the gift-bag procedure. For impulsivity, mothers’ and caregivers’ reports were indicators. For committed compliance, the composite of adults’ reports of compliance and observed committed compliance (combined responses from cleanup and don’t touch) were indicators. Correlations among the latent factors within time were estimated. Unique variances of the study variables were allowed to covary within reporter when indicated by the modification indices. The models were tested using Mplus (Version 4.2; Muthén & Muthén, 2002). Under the missing at random assumption, the models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood, which allows for missing data. Model fit was assessed with the chi-square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), and the root-mean-square of approximation (RMSEA). Nonsignificant chi-square statistics, CFIs greater than .90, and RMSEAs less than .08 indicate an adequate model fit, although the chi-square statistic is affected by sample size and, consequently, was not considered the primary indicator of fit (Kline, 1998).

The measurement model fit the data adequately, χ2(184, N = 235) = 283.98, p < .01, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .05 (90% confidence interval [CI] = .04 to .06). All of the model-estimated loadings were significant and in the expected direction (i.e., all positive loadings). In addition, correlations among the constructs within time showed that at each time point maternal sensitivity/warmth was positively correlated with EC and committed compliance and was negatively correlated with impulsivity. Moreover, EC was positively correlated with committed compliance and negatively correlated with impulsivity at each age. Committed compliance also was negatively related to impulsivity at each age.

Next, we examined the invariance of the loadings for indicators to test whether the relations of the latent variables to the manifest variables were constant over time. Constraints were kept if they did not produce a significant reduction in fit (using chi-square difference tests). All constraints were set to be equal across waves, which produced a significant reduction in fit, χ2(192, N = 235) = 311.11, p < .01, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .04 to .06), Δχ2(8) = 27.13, p < .01; thus, the loading for maternal warmth at T4 was allowed to be freely estimated, χ2(191, N = 235) = 297.45, p < .01, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .04 to .06). The resulting measurement model did not produce a reduction in fit compared with the fully unconstrained model, Δχ2(7) = 13.47, p > .05. All model-estimated loadings are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Standardized and Unstandardized Loadings in Measurement Model

| Variable | Time 2

|

Time 3

|

Time 4

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstdz | Stdz | Unstdz | Stdz | Unstdz | Stdz | |

| Parenting | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .88 | 1.00 | .83 |

| Warmth | 0.56** | .44 | 0.56** | .61 | 1.09** | .70 |

| Effortful Control | ||||||

| Gift bag score | 1.00 | .12 | 1.00 | .24 | 1.00 | .34 |

| Adult EC | 2.04** | .69 | 2.04** | .98 | 2.04** | .86 |

| Impulsivity | ||||||

| Caregiver Imp | 1.00 | .54 | 1.00 | .54 | 1.00 | .61 |

| Mother Imp | 0.63** | .37 | 0.63** | .38 | 0.63** | .41 |

| Compliance | ||||||

| Adult comply | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .76 | 1.00 | .81 |

| Observed comply | 0.25** | .24 | 0.25** | .18 | 0.25** | .23 |

Note. Unstdz = unstandardized; Stdz = standardized; EC = effortful control; Imp = impulsivity; comply = compliance.

p < .01.

Hypothesized models

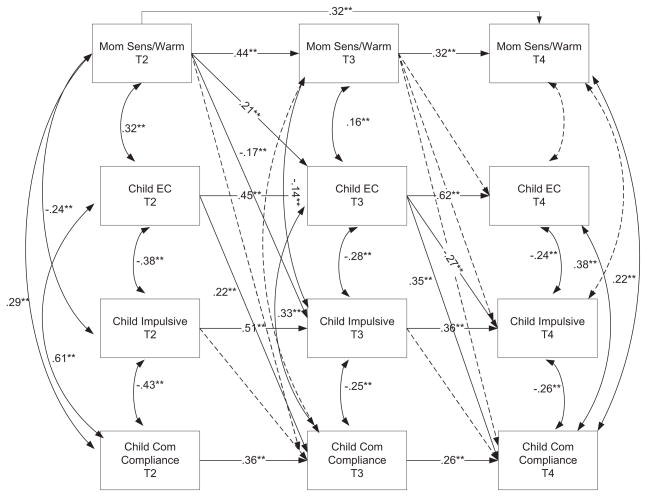

Because of our relatively small sample size and the number of indicators in the model, composite scores were created as single indicators of each construct. The composite scores were created by summing the weighted scores of measures using the unstandardized weights from the partially constrained measurement model and by dividing the sum of the weights. In cases of missing data, the weighted scores of valid data were summed and divided by the sum of the valid weights. Using this path model, we tested whether parenting at the first two time points (T2 or T3) predicted EC and impulsivity a year later (T3 or T4), and whether T2 or T3 EC predicted committed compliance a year later (T3 or T4). The model fit the data adequately (Kline, 1998), χ2(30, N = 235) = 93.94, p < .01, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .10 (90% CI = .07 to .12). Inspection of the modification indices indicated that two paths should be added: (a) a path from T2 parenting to T4 parenting and (b) a path from T3 EC to T4 impulsivity. The estimation of the suggested parameters improved the fit, χ2(28, N = 235) = 62.163, p < .01, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .07 (90% CI = .05 to .10). The autoregressive paths for all of the constructs were positive and significant (see Figure 1), and the added path from T2 sensitivity to T4 sensitivity was positive and significant. The paths from T2 mother sensitivity to high EC and low impulsivity a year later were significant, although the paths from T3 mother sensitivity to T4 EC and impulsivity were not significant after controlling for stability in the constructs. Impulsivity did not predict later committed compliance. T2 and T3 EC predicted higher committed compliance a year later. In addition, T4 impulsivity was negatively predicted by T3 EC. In terms of concurrent correlations among the major constructs, T2 maternal sensitivity was positively related to concurrent EC and negatively related to concurrent impulsivity; moreover, maternal sensitivity was positively related to concurrent committed compliance at T2 and T4 (even when taking stability into account for T4), but not at T3. EC was positively related to committed compliance and negatively related to impulsivity at all ages. Impulsivity was negatively correlated with concurrent committed compliance at all ages. Mediated effects were tested using Sobel’s (1982) product coefficient test, as outlined by MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (2002). EC significantly mediated the relations between T2 sensitivity and T4 committed compliance (z = 2.51). In addition, EC mediated the relation between T2 sensitivity and T4 impulsivity (z = −2.41).

Figure 1.

Traditional path model. Sens/Warm = sensitivity and warmth; EC = effortful control; Com = committed. Dashed lines indicated nonsignificant paths/correlations. **p < .01.

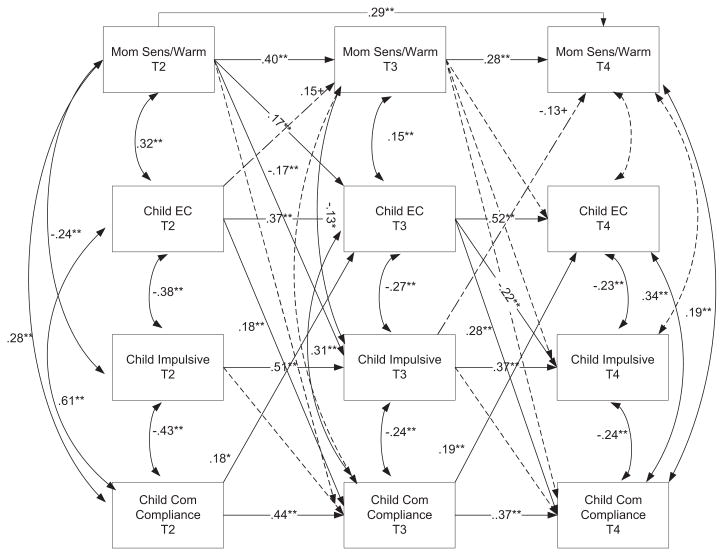

We also tested a bidirectional cascade model, in which we added paths from EC and impulsivity at T2 and T3 to mothers’ sensitivity a year later and paths from committed compliance at T2 and T3 to mothers’ sensitivity, impulsivity, and EC a year later. The fit of this model was a significant improvement from the previous model, χ2(18, N = 235) = 39.99, p < .01, CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 (90% CI = .04 to .10), Δχ2(10) = 22.17, p < .05. There were two positive and significant paths from T2 and T3 committed compliance to EC a year later. No paths from committed compliance to later impulsivity or maternal sensitivity were significant. There were two additional bidirectional paths that approached significance. Specifically, T2 EC marginally predicted higher maternal sensitivity/warmth a year later, whereas T3 impulsivity marginally negatively predicted maternal sensitivity/warmth a year later, and all paths in the previous model were maintained (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Traditional path model including significant or marginal bidirectional paths. Sens/Warm = sensitivity and warmth; EC = effortful control; Com = committed. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths/correlations. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Random and fixed effect models

To determine if the above findings could be explained by omitted time-invariant variables, we conducted two models: a random-effects panel model and a fixed-effects panel model. The primary advantage of these models is that they control time-invariant variables that may not have been observed in this study.

These models include a latent intercept factor for which the repeated measures of the outcome variable, committed compliance, were indicators with factor loadings set to 1. The intercept factor introduces a latent effect for each subject into the model. The latent effect for each subject controls for the potential effect of omitted time-invariant variables (Allison, 2005; Bollen & Brand, 2010). In addition, we included within-time paths from parenting, EC, and impulsivity to committed compliance, and these paths were constrained to be equal across time. In the random-effects model, the correlations between the latent intercept factor and parenting, EC, and impulsivity at each age are set to zero, and in the fixed-effects model, these correlations are estimated.

The random-effects model had adequate fit, χ2(26) = 68.18, p < .01, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .06 to .11). In terms of the within-time paths, committed compliance was significantly predicted by high EC and low impulsivity and was near significantly predicted by high sensitivity. In addition, the fixed-effects model had good fit, χ2(17) = 31.12, p < .01, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .03 to .09). Committed compliance was significantly predicted by high EC, high sensitivity, and low impulsivity at each age. Because the fixed-effects model allows the latent intercept factor to correlate with parenting, EC and impulsivity, these correlations were examined, and those between the intercept factor and EC at T1, T2, and T3 were significant, indicating that the association between these variables and committed compliance may be biased by omitted time-invariant variables.

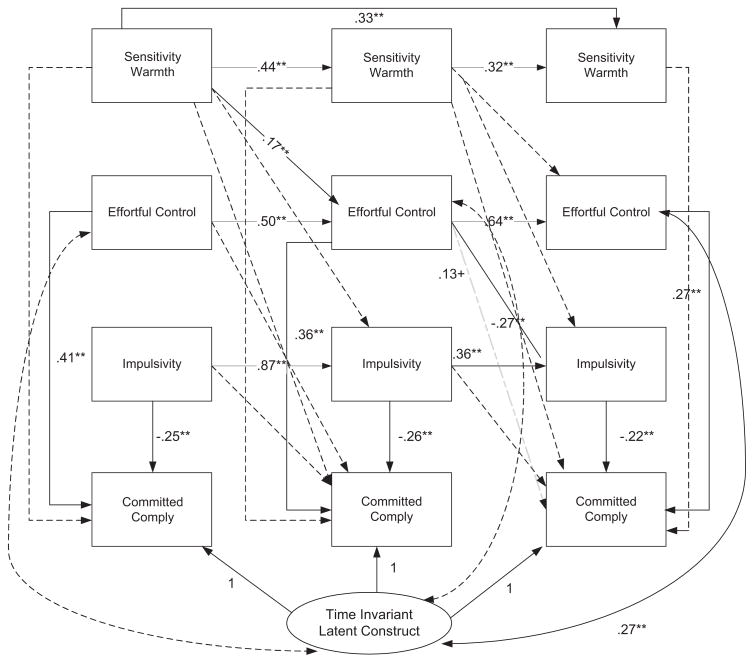

Next, the Hausman (1978) chi-square test was used to compare the random versus fixed effects model by taking the difference in their respective degrees of freedom and chi-square values. This test was statistically significant, Δχ2(9) = 37.06, p < .01, indicating that the fixed effects model is preferable. Because the results above provided evidence for using a fixed effects model, we then tested our meditational hypotheses in which we calculated the autoregressive and cross-lagged effects using a hybrid fixed-effects model. Because only the correlations between EC at each time and the intercept factor were significant, all other correlations with the intercept factor were set to zero. The fit of this model was good, χ2(31) = 66.46, p < .01, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .07 (90% CI = .05 to .09). All of the autoregressive paths were positive and significant. In terms of the within-time paths, at all ages, EC significantly positively predicted and impulsivity negatively predicted committed compliance. In terms of the cross-lagged paths, similar to the traditional model (without fixed effects), T2 sensitivity predicted T3 EC (but not T3 impulsivity). The path from T3 EC to T4 impulsivity also was negative and significant (as was found in the traditional model). The positive path from T3 EC to T4 committed compliance dropped to marginal significance, and the path from T2 EC to T3 committed compliance was no longer significant, indicating that time-invariant variables unmeasured in this study account for the relations between EC and committed compliance over time, as well as for the relation between T2 sensitivity and later low impulsivity (see Figure 3). We also computed a fixed-effects model in which bidirectional paths were included; none was significant.

Figure 3.

Fixed effects path model. Dashed lines indicate non-significant paths/correlations. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Discussion

In the current study, the role of parenting on children’s EC and impulsivity to their committed compliance from 30 to 54 months of age was examined. Overall, the findings provided evidence that early parenting predicted children’s EC over time, even in the most stringent models controlling for time-invariant covariates. Moreover, there was some evidence in traditional path models that EC, but not impulsivity, was related to committed compliance over time, even when controlling for stability in committed compliance. Interestingly, in path models, committed compliance also predicted higher EC a year later. Finally, there was evidence that EC predicted later lower impulsivity, even when controlling for time-invariant covariates.

First and foremost, we found that maternal warmth and sensitivity observed at 30 months predicted young children’s EC a year later. That is, when mothers behave in child-centered ways, children likely maintain optimal levels of arousal and are able to regulate their arousal when needed, which may serve to directly teach children ways to deal with emotions in the future. Indeed, sensitive caregiving has been linked to children’s high regulatory skills (Belsky et al., 2007; Li-Grining, 2007; Spinrad et al., 2007). In contrast, disapproving or punitive responses to children’s emotions may induce arousal and dysregulation in children (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010). The findings of the current study highlight the role of socialization practices in early childhood, when self-regulation is developing (Kochanska et al., 2000).

It is important to note, however, that we did not find that maternal sensitivity/warmth at 42 months predicted later EC. There are a number of possible reasons for these relations. First, perhaps our lack of findings is due to the high stability of parenting over time. Because our stringent analyses require that we control for stability over time, any findings for parenting effects on EC are above and beyond the stability effects and prior cross-lagged paths from parenting to EC. In work using the same sample, Spinrad et al. (2007) and Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al. (2010) found that supportive parenting at a younger age (18 months) predicted high EC at 30 months of age, even when controlling for stability over time, even though parenting at the later ages did not predict later EC. Thus, it appears that the impact of later parenting is likely due to stability in the constructs over time. On the other hand, it may be that other forms of parenting predict EC at later ages. It may be that more negative, controlling, or hostile parenting behaviors have a stronger impact on children’s regulation skills. Indeed, in a meta-analysis, Karreman, Van Tujil, van Aken, and Dekovic (2006) showed that parental control, but not responsiveness, was significantly associated with self-regulation, although the authors demonstrated that this relation was only significant when predicting children’s compliance, which they considered an aspect of self-regulation. Nonetheless, parenting in more evocative contexts that elicit parental negativity, such as parent– child conflicts, should be studied.

In the traditional path models, we found that children’s EC, but not impulsivity, at both 30 and 42 months of age was predictive of committed compliance a year later. Indeed, in these models, we found evidence that EC mediated the relation between parenting and children’s committed compliance over time. There is no work to date in which children’s EC and committed compliance have been subject to longitudinal mediation tests while accounting for stability in the outcomes over time, and this study adds to existing evidence of the mediational role of EC to children’s outcomes (Belsky et al., 2007; Eisenberg, Valiente, Morris, et al., 2003; Kochanska & Knaak, 2003; Spinrad et al., 2007). Thus, in addition to the impact of parenting on children’s EC, children who are able to control their attention and behavior are more cooperative and likely to have less difficulty redirecting their efforts from playing to putting toys away or exploring restricted toys (Gilliom et al., 2002; Kochanska et al., 1997, 1998, 2001). On the other hand, children who are have poor EC abilities may have difficulty internalizing standards of behavior (Hill & Braungart-Rieker, 2002; Kochanska & Aksan, 1995; Kochanska et al., 1998) or may exhibit forms of noncompliance, such as defiance (Stifter, Spinrad, & Braungart-Rieker, 1999). The fact that committed compliance was predicted by earlier EC at both later time points (42 and 54 months) and that results remained, even when controlling for earlier levels of committed compliance gives particular credence to these findings.

It is important to note, however, that the relations between EC and children’s committed compliance were no longer significant in models in which time-invariant covariates were considered, indicating that the relations between EC and committed compliance are influenced by variables unmeasured in the present study but that clearly impact the findings. There are a number of variables that may have accounted for the relation between EC and committed compliance, such as race, sex, SES, developmental level, and parental personality. Although the fixed-effects models do not specifically indicate what variables may account for the findings per se, these models control for the effects of all potential time-invariant covariates.

The findings from this study also demonstrated that impulsivity and EC could be empirically differentiated; the fact that EC, but not impulsivity, uniquely predicted children’s later committed compliance provided additional evidence of discriminant validity of the constructs. These constructs have been differentiated and negatively related to each other in other work (Aksan & Kochanska, 2004; Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2004; Spinrad et al., 2006) but rarely in such a young sample. Moreover, the negative relation between EC and later impulsivity suggests that as children gain EC, they may learn to manage their reactive undercontrol—that is, as children improve in their EC skills, they also use it to manage the manifestations of their impulsivity. Although impulsivity did not predict children’s committed compliance over time, it is important to acknowledge that within-time correlations of the latent constructs indicated that impulsivity was related to lower concurrent committed compliance at T2 and T3.

The relation between parenting and impulsivity also was particularly interesting. We did not expect parenting to predict impulsivity because of the view that impulsivity is a more reactive and involuntary construct than is EC; thus, it is possible that socialization practices may have less influence on such behaviors than on EC (Eisenberg, Chang, Ma, & Huang, 2009). However, in the path models, we found that early sensitive parenting predicted low impulsivity a year later, and other researchers have found family environment to predict children’s impulsivity (Eisenberg, Chang, et al., 2009; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2003). Recently, Graziano, Keane, and Calkins (2010) found that while maternal behavior characterized by overcontrol and intrusiveness was marginally related to lower levels of growth in impulsivity, maternal caregiving was more strongly related to children’s EC. These findings support the notion that impulsivity may have biological underpinnings but also may be affected to some degree by the social environment. Given that EC also mediated the relations between parenting and impulsivity, it is possible that the relations between parenting and impulsivity are indirect.

We also found evidence of that children’s committed compliance predicted later improved EC. The skills required to stop an enjoyable activity to cleanup toys or refrain from touching an attractive object may provide important practice for the development of similar behaviors involved in EC. Children who actively select and internalize their parents’ ideas and goals also may be open to learning new strategies for regulating their behavior and attention over time. Moreover, when children are generally compliant and obedient, parents may provide children more opportunities that promote self- regulation skills, such as allowing children more independence. Conversely, when children lack committed compliance, parents may become more coercive or controlling over time, which, in turn, may shape children’s lower regulation skills. Although these findings were limited to the traditional panel models, it is important to address potential bidirectional relations in future studies.

Among the strengths of this study was the three-wave longitudinal design, including the same measures of the constructs over time that, for the most part, demonstrated invariance across time. It is important to use such designs to assess potential causal pathways. In addition, we used multiple reporters and methods, including parents’ and teachers’ reports and observations of parenting and EC, which are not likely to reflect reporter bias. A final strength of the investigation was the additional use of a hybrid fixed-effects approach to control for time-invariant omitted variables. This strategy is seldom taken in behavioral and developmental research; however, this approach gave us particular confidence in some of our findings (i.e., the relations of maternal sensitivity to later EC and EC to lower impulsivity) and indicated that for some findings (i.e., the relations of EC to committed compliance), time-invariant covariates contributed to the relations. Researchers should continue to use such stringent methods in their longitudinal research (Bollen & Brand, 2010).

Despite these strengths, several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, as children developed, committed compliance, particularly during the prohibition task, may have approached a ceiling, calling the validity of this measure at older ages into question. This problem is not surprising, given that children increasingly need less adult support to comply with requests during the preschool years. Indeed, Kochanska et al. (2001) found that committed compliance in a prohibition context rose by 45% between 14 and 22 months (and was at 90% and 85% at 33 and 45 months, respectively). Because we took the strategy of combining the prohibition and cleanup tasks in our study, we increased the variability of the observed compliance variable at this age. This measure also was combined with parent and teacher reports, further increasing the validity of our composite. Moreover, in the traditional path models, EC still predicted committed compliance at the older ages. Thus, we have relative confidence in our committed compliance measure. In addition, the sample was predominantly Caucasian and from middle-class backgrounds, reducing the generalizability of our findings. Finally, we focused on the relations of mothers’ parenting behaviors, rather than also including fathers’ behaviors. Thus, the generalizability of the study is restricted to mothers.

Future research should examine additional complex relations. For example, the potential moderating effects of emotional reactivity (i.e., anger proneness) on the relations of EC to committed compliance and defiance should be addressed. That is, it is possible that the link between EC and committed compliance is stronger for children who are in more need of regulation—those who are prone to anger or defiance (Stifter et al., 1999). Similarly, the link between parenting to EC might depend on similar factors, such as emotional reactivity. Belsky and colleagues (Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Belsky, 2005) proposed that “at risk” children may be more susceptible to parenting behaviors than their peers. In other words, children who are more negatively reactive may be more affected (positively or negatively) by parenting behaviors, which, in turn, may impact outcomes such as EC. Finally, although in the current investigation, children’s reactive undercontrol (i.e., impulsivity) was examined, it is also important to address the role of children’s behavioral inhibition (i.e., reactive overcontrol) on children’s committed compliance over time.

Nonetheless, this study provided insight into the relations of EC and committed compliance over time. Although we obtained evidence that EC predicts committed compliance longitudinally, the findings also suggested that some of the relations of maternal behaviors to temperament may be set at an early age.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by National Institute of Mental Health Grant 5 R01 MH60838 to Nancy Eisenberg and Tracy L. Spinrad. We would like to thank the children, parents, and teachers involved in the current study. In addition, we appreciate our undergraduate research assistants for their contributions.

Contributor Information

Tracy L. Spinrad, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

Nancy Eisenberg, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Kassondra M. Silva, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

Natalie D. Eggum, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

Mark Reiser, School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, Arizona State University.

Alison Edwards, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Roopa Iyer, Advanced Studies in Learning, Technology, and Psychology in Education, Arizona State University.

Anne S. Kupfer, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Claire Hofer, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Cynthia L. Smith, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Akiko Hayashi, Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Curriculum and Instruction, Arizona State University.

Bridget M. Gaertner, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

References

- Aksan N, Kochanska G. Links between systems of inhibition from infancy to preschool years. Child Development. 2004;75:1477–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Differential susceptibility to rearing influence: An evolutionary hypothesis and some evidence. In: Ellis BJ, Bjorklund DF, editors. Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pasco Fearon RM, Bell B. Parenting, attention and externalizing problems: Testing mediation longitudinally, repeatedly and reciprocally. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:1233–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandon AY, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Predicting emotional and social competence during early childhood from toddler risk and maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;2(2):119–132. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J. The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In: Andrew Collins W, editor. Development of cognition, affect, and social relations. The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology. Vol. 13. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1980. pp. 39–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Brand JE. A general panel model with random and fixed effects: A structural equations approach. Social Forces. 2010;89:1–34. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker J, Garwood MM, Stifter CA. Compliance and noncompliance: The roles of maternal control and child temperament. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1997;18:411–428. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(97)80008-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Vandergrift N, Belsky J, Burchinal M The NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Predictors and sequelae of trajectories of physical aggression in school-age boys and girls. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:133–150. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, Little TD. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:495–514. doi: 10.1023/A:1025449031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Litman C. Autonomy as competence in 2-year-olds: Maternal correlates of child defiance, compliance, and self-assertion. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:961–971. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.26.6.961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JN, Kliewer W, Garner PW. Emotion socialization, child emotion understanding and regulation, and adjustment in urban African American families: Differential associations across child gender. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:261–283. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. Developmental time course in human infants and infant monkeys, and the neural bases of inhibitory control in reaching. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1990;608:637–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb48913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N. Emotion-related regulation and its relation to quality of social functioning. In: Hartup W, Weinberg RA, editors. Child psychology in retrospect and prospect: In celebration of the 75th anniversary of the Institute of Child Development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 133–171. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Chang L, Ma Y, Huang X. Relations of parenting style to Chinese children’s effortful control, ego resilience, and maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:455–477. doi: 10.1017/S095457940900025X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Eggum ND, Sallquist J, Edwards A. Relations of self-regulatory/control capacities to maladjustment, social competence, and emotionality. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Handbook of personality and self-regulation. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Smith CL, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL. Effortful control: Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL. Emotion-related regulation: Sharpening the definition. Child Development. 2004;75:334–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:495–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND, Silva KM, Reiser M, Hofer C, Michalik N. Relations among maternal socialization, effortful control, and maladjustment in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:507–525. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, Thompson M. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Smith CL, Reiser M, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ. The relations of effortful control and ego control to children’s resiliency and social functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:761–776. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Morris AS, Fabes RA, Cumberland A, Reiser M, Losoya S. Longitudinal relations among parental emotional expressivity, children’s regulation, and quality of socioemotional functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Losoya SH. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Klein PS. Toddlers’ self-regulated compliance to mothers, caregivers, and fathers: Implications for theories of socialization. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:680–692. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish M, Stifter CA, Belsky J. Conditions of continuity and discontinuity in infant negative emotionality: Newborn to five months. Child Development. 1991;62:1525–1537. doi: 10.2307/1130824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS, Beck JE, Schonberg MA, Lukon JL. Anger regulation in disadvantaged preschool boys: Strategies, antecedents, and the development of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:222–235. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Keane SP, Calkins SD. Maternal behaviour and children’s early emotion regulation skills differentially predict development of children’s reactive control and later effortful control. Infant and Child Development. 2010;19:333–353. doi: 10.1002/ICD.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendyk AE, Volling BL. Coparenting and early conscience development in the family. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2007;168:201–224. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.168.2.201-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Nuselovici JN, Utendale WT, Coutya J, McShane KE, Sullivan C. Applying the polyvagal theory to children’s emotion regulation: Social context, socialization, and adjustment. Biological Psychology. 2008;79:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman JA. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica. 1978;46:1251–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Hill AL, Braungart-Rieker JM. Four-month attentional regulation and its prediction of three-year compliance. Infancy. 2002;3:261–273. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman A, van Tuijl C, van Aken MAG, Dekovic M. Parenting and self-regulation in preschoolers: A meta-analysis. Infant and Child Development. 2006;15:561–579. doi: 10.1002/icd.478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw D, Delliquadri E, Giovannelli J, Walsh B. Evidence for the continuity of early problem behaviors: Application of a developmental model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:441–452. doi: 10.1023/A:1022647717926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Brody GH. Longitudinal pathways to psychological adjustment among black youth living in single-parent households. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:305–313. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Children’s temperament, mother’s discipline, and security of attachment: Multiple pathways to emerging internalization. Child Development. 1995;66:597–615. doi: 10.2307/1131937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: From toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:228–240. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Committed compliance, moral self, and internalization: A mediational model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:339–351. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N. Mother–child mutually positive affect, the quality of child compliance to requests and prohibitions, and maternal control as correlates of early internalization. Child Development. 1995;66:236–254. doi: 10.2307/1131203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]