Abstract

An unprecedented number of Americans have been incarcerated in the past generation. In addition, arrests are concentrated in low-income, predominantly nonwhite communities where people are more likely to be medically underserved. As a result, rates of physical and mental illnesses are far higher among prison and jail inmates than among the general public. We review the health profiles of the incarcerated; health care in correctional facilities; and incarceration’s repercussions for public health in the communities to which inmates return upon release. The review concludes with recommendations that public health and medical practitioners capitalize on the public health opportunities provided by correctional settings to reach medically underserved communities, while simultaneously advocating for fundamental system change to reduce unnecessary incarceration.

Keywords: prisons, war on drugs, health disparities, underserved communities, medical training

INTRODUCTION

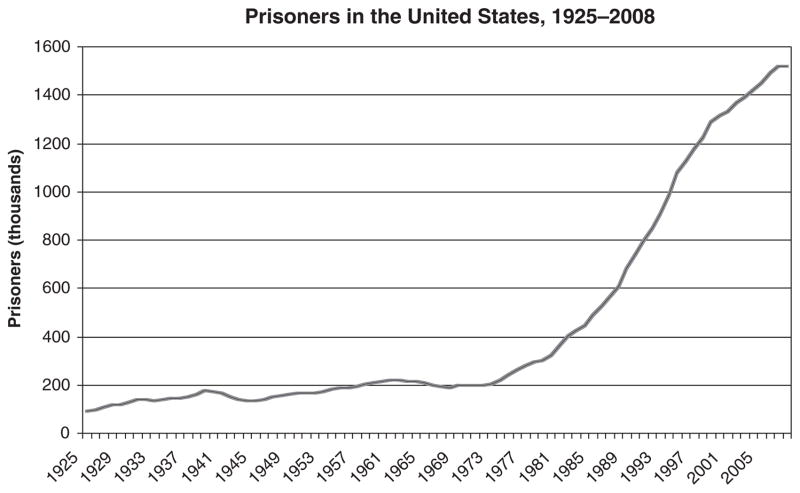

No other citizenry in the world is as subject to incarceration as that of the United States (64, 65). After moderately stable rates for most of the twentieth century, the number of Americans in prison or jail accelerated so rapidly starting in the 1970s that legal scholars widely use the phrase mass incarceration to describe its scale, although other scholars have suggested the term hyperincarceration to reflect better the concentration of incarceration in impoverished, predominantly nonwhite communities (Figure 1). The surge was caused by no sudden intensification of criminal instincts among Americans; nor was it the result of a sudden improvement in police effectiveness in capturing criminals. It is instead a story of politics and policy with significant racial implications and consequences for health disparities.

Figure 1.

Incarceration trends in the United States, 1925–2008.

Observers have noted for years that the war on drugs, now 40 years old, was largely responsible for the unprecedented escalation of incarceration, but the 2010 publication of Michelle Alexander’s (1) description of the workings and effects of that war has provided a newly comprehensive framework for understanding how it came to disproportionately imprison people of color. Even setting aside Alexander’s argument regarding the original intent of the war on drugs and its conduct in subsequent decades, a generation of evidence leaves no doubt that the war on drugs has had profoundly different effects on people of color than on whites.

Then-President Richard Nixon’s declaration of a war on drugs came at a time of social and political reaction against the civil rights movement and the social turmoil of the 1960s. “Tough on crime” rhetoric was understood as a way to employ language that was racially coded, but not so explicitly racist that it could be challenged as such. Nixon’s chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, remembered Nixon emphasizing “the fact that the whole problem [of creating a Republican mass base] is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to”—a system in which, as John Ehrlichman said, “the subliminal appeal to the antiblack voter was always present in Nixon’s statements and speeches” (both quoted in Reference 1).

State and local law enforcement initially resented the war on drugs as a diversion of resources from more serious crime, but generous grants from the federal government soon lured them into enthusiastic participation, even as drug use was already declining. Politicians of both major parties courted voters by being tough on crime, and escalating arrest rates for possession of drugs were accompanied by a series of laws setting mandatory long sentences for drug offenses, to the point where even judges with a reputation for sternness were appalled by the severity of sentences they now had to pronounce on low-level and first-time offenders.

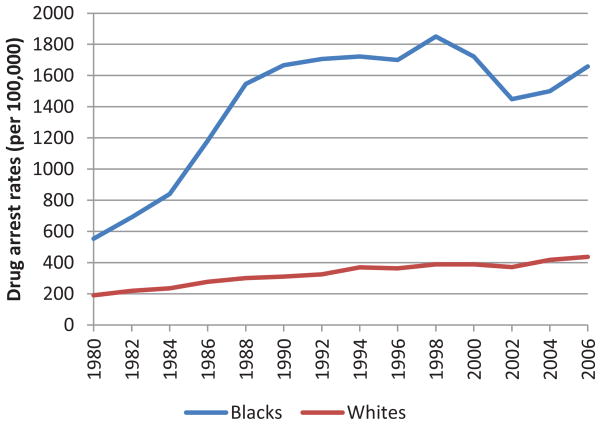

These structural changes did not affect all demographics equally. Illicit drug use among U.S. whites is 8.8%; among blacks, it is 9.6% (81). The latter, though, are more than 13 times more likely to be imprisoned for drug charges and constitute 62% of those imprisoned as a result of the war on drugs (61). Blacks became particularly associated with crack in the public and law-enforcement mind, and although they constitute only 15% of all crack users, they account for more than 85% of those sentenced under mandatory minimums for crack (37). Police and judicial systems have focused their energies not on the largely white college dormitories and fraternity houses where drug use has long been common, but instead on black drivers and pedestrians in lower-income communities, who are frequently stopped in random searches. The result has been that the twenty-first century opened with blacks disproportionately arrested and incarcerated to a greater extent than they were during the Jim Crow 1920s (33; see Figure 2). The war on drugs by no means accounts for the entire incarcerated population, but it does encompass a substantial percentage of those in prisons and jails, about two-thirds of the rise in the federal inmate population and one-half of the state inmate population between 1985 and 2000 alone. (Among drug arrests, marijuana possession accounted for 80% of the growth in the 1990s.) A growing number of entities such as the Global Commission on Drug Policy have denounced its failure to reduce drug sales and use. And because it is concentrated in low-income, predominantly nonwhite communities that were already decimated by the disappearance of jobs as industries moved away from urban centers in the 1960s (85, 86) its health implications are wide-ranging for both the incarcerated themselves and their communities.

Figure 2.

Arrest rates for drug offenses by race, 1980–2006. Source: Human Rights Watch, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/us0309web_1.pdf.

HEALTH IN THE CORRECTIONAL SETTING

Although our understanding of incarcerated populations has been significantly enriched by research in the past ten years, gaps in some subject areas and the wide range of point estimates for some conditions are a reflection of continued limitations on research and practice. It is clear that even within this overall highly disadvantaged population, a health profile of people in prisons and jails reflects dramatic disparities by race and gender. Few studies, though, have looked beyond black-white breakdowns to examine whether Latinos or other racial/ethnic categories have distinct health patterns associated with incarceration. Our knowledge is further challenged by the different structures and populations of prisons and jails, making it difficult to generalize about the incarcerated as a whole. State and federal prisons house those sentenced to more than one year. Jails, under county or municipal jurisdiction, house a larger population of those awaiting trial, sentencing, or transfer to prison; parole or probation violators; and those sentenced to less than one year. As a result, jails experience high turnover and affect a far greater swath of the population: about 13 million admissions and releases annually, involving ~9 million different individuals. The high turnover makes screening and health care far more challenging, but it also creates opportunities to access a wide swath of communities frequently inaccessible to public health initiatives.

Physical Health Profile of the Incarcerated

Reflecting the concentration of incarceration among low-income people, who are more likely to be medically underserved, the incarcerated have far more health problems than does the general population. Researchers have especially focused on tuberculosis (9, 53) and HIV in correctional facilities, although the precise number of people living with HIV behind bars still remains uncertain, in part because estimates based on the U.S. population at large indicate that ~25% of HIV-infected individuals do not know their positive status. New York City jails reflect national trends in a decline of nearly 50% in the percentage of HIV-positive inmates over the course of the 1990s, from 18.4% to 9.7% (30), but despite these gains, HIV prevalence remains ~5 times higher in state/federal corrections than in the general public: 1.6% among male inmates and 2.4% among female inmates, compared with 0.36% in the total U.S. population for 2006 (10, 35, 52, 56, 78). However, blinded seroprevalance studies in New York revealed HIV rates of more than 5% for male and more than 10% for female inmates (56).

We are also becoming more familiar with trends in the comorbidity of HIV and other conditions, particularly given the concomitant high-risk behaviors and circumstances associated with substance abuse and mental illness. The paths of transmission for HIV—above all, injection—put the same individuals at high risk for hepatitis C virus (HCV), at rates 9–10 times higher among the incarcerated than among the nonincarcerated (28). Because patients co-infected with both HIV and HCV have also been found to have more comorbidities than HIV mono-infected patients, inmates are likely to carry a greater overall burden of coexisting diseases; futhermore, as sensitivity of self-reported HCV ranged from 66% to 77% in 3 studies, this medically underserved population may be frequently unaware of those comorbid conditions (94). Syphilis, which was close to total eradication a few years ago, also has unparalleled rates among incarcerated women; Freudenberg (29) found that early syphilis among women in New York jails exceeded the general city rate by more than 1000-fold. Whereas men are more likely to be arrested for almost every other offense, women’s predominance in prostitution (frequently to support an addiction) concentrates them in a notoriously high-risk activity for infectious disease transmission (93).

Chronic diseases have received less attention by comparison, but that may change as a result of two developing trends: the emergence of chronic conditions such as diabetes among younger people, partly stemming from the obesity epidemic, and the aging of the incarcerated population, especially with the imposition of longer sentences in the 1980s and 1990s. In Texas, the number of inmates 55 and older increased by 148% between 1994 and 2002, compared with a 32% increase in the overall state criminal justice population (68). In addition, there is a suggestion that chronic conditions tend to be at a more advanced stage among the incarcerated, compared with the age-adjusted general public (83). It is already evident that more chronic care will be required; between 39% and 43% of inmates (depending on the facility type) are diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, asthma, or another chronic condition, rates consistently higher than among the general population (12, 13, 97). On the other hand, obesity among prison inmates is only minimally higher than in the general population and indeed lower among jail inmates (12). Overall, however, inmates in both prisons and jails constitute a medically complex population not captured in national health surveys.

Mental Health Profile of the Incarcerated

Although not all overviews of the health profiles of the incarcerated include addiction (25, 97), it is among the primary conditions both determining involvement in the criminal justice system and requiring—though seldom receiving—treatment during incarceration. Estimates of the number of the incarcerated meeting DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) criteria for drug dependence or abuse vary widely but are well above 50%, and substantially higher among female inmates (12, 28, 37, 41). However, as few as 15% of inmates in need of drug treatment actually receive it during incarceration (11, 17, 27).

Rates of comorbidity of substance abuse and mental illness are high, as people attempt to self-medicate for the latter or are subject to overlapping personal and environmental risk factors for both conditions. Both conditions are overrepresented in the criminal justice system; both are conditions that in white, middle-class communities are more likely to receive treatment than the attention of law enforcement (37). The emergence of prisons and jails as the largest institutions in the United States housing the mentally ill reflects the de facto criminalization of mental illness. The front line of that process is the police, who frequently determine whether someone will enter the mental health system or the criminal justice system. Even police who are equipped and inclined to recognize mental illness and respond appropriately, however, find themselves constrained to redirect the mentally ill into the criminal justice system, frequently by the failures of the mental health system to which they attempt to turn (23, 47, 49). Thus a primarily nonviolent, mentally ill population cycles repeatedly through correctional facilities (5, 8), with the result that well over half of inmates at any given time have a DSM-IV mental disorder. Rates vary by facility type as well as by demographics, with local jails reflecting the highest prevalence: There, 63% of blacks and 71% of whites self-reported symptoms or diagnoses of mental illness (26, 37, 41). An estimated 16–24% have a serious mental illness (SMI) (47), among whom the comparatively small number of female inmates tends to be much worse off (7, 13). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common among incarcerated women, about one-third of whom were subject to physical abuse and one-third to sexual abuse prior to incarceration (51). The potential for physical comorbidities is correspondingly heightened for this population because women with SMI are substantially more likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors (59). Addictions and other mental illnesses also complicate treatment for comorbidities such as HIV and HCV, which require a sustained adherence regime and careful monitoring for adverse drug interactions (3).

Incarceration as Health Risk

At first sight, incarceration appears to provide a protective health influence to many of the underserved who enter the criminal justice system, particularly those from violent or homeless backgrounds. However substandard, the system provides shelter and meals; it also enforces supervision and highly-structured routines, a stabilizing force for some. Moreover, several recent studies of inmate mortality rates appear to indicate that the black-white mortality gap shrinks within correctional facilities because black male inmates’ mortality rate is lower than that of the general black male population but white male inmates’ mortality rate is either the same or slightly higher than that of the general white male population (63, 73, 77). However, the protective effect of incarceration is revealed to be illusory by the surge in mortality in the weeks following release (see below). As the 2011 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Plata revealed, overcrowding in many correctional facilities raises serious health concerns, even more on account of overstretched health services than the potential for infectious disease outbreaks (4).

Incarceration also exposes inmates to new health risks, e.g., high-risk sexual behaviors (whether voluntary or coerced, with little access to condoms) and shared needles for drug use and tattooing (10, 66, 67, 72). However, Beckwith et al. (10) find that the rates of HIV transmission through these channels are lower than in the general population, and most infectious diseases are acquired prior to, rather than during, incarceration. Incarceration contributes more to adverse outcomes related to addiction and mental illness than to the transmission of infectious diseases. Although methadone is widely used to treat opioid addictions, few correctional facilities are willing to initiate or continue that treatment for inmates already on methadone upon entry (16, 34, 54, 60, 62, 70, 92), leaving the addicted subject to withdrawal during incarceration and more vulnerable to overdose upon release. Those with behavioral issues are more vulnerable to placement in “supermax” facilities, an environment particularly hazardous to the mentally ill (36, 69). Unlike traditional solitary confinement, supermax enforces near-total isolation and has been shown to elicit a range of adverse responses from anxiety and rage to hallucinations and self-mutilation after as little as ten days; prisoners with preexisting mental illnesses are especially vulnerable to permanent effects of such seclusion (36).

Incarceration as Opportunity: Health Care in Prisons and Jails

Incarceration has been associated with poor long-term health outcomes, and because people of color are incarcerated far more frequently than whites, the experience may ultimately exacerbate rather than mitigate health disparities (40, 57, 58, 95). Yet correctional facilities still hold the possibility of linking the medically underserved to health care, providing a potential counterbalance to incarceration’s contributions to health disparities. Among the ironies of contemporary social and political attitudes regarding prisoners in the United States is that the incarcerated constitute almost the only group that has a constitutional right to health care (Native Americans are the other). In Estelle v. Gamble (1976), the U.S. Supreme Court found that the deliberate failure to provide adequate medical treatment to prisoners constituted cruel and unusual treatment (4). The mandated provision of health care in correctional facilities is all the more important because many inmates lack health insurance prior to incarceration, and Medicaid coverage is either suspended or terminated (depending on the state) upon incarceration. As a result, 90% of people released from jail lack coverage and thus access to most health services (91). Particularly for those who will be reincarcerated, correctional facilities can provide the only sustained contact with a health care system.

The actual extent of access to health care remains unclear, though, and its quality varies considerably across facilities. All facilities offer some screening, particularly for HIV, but only 7% screen routinely (10). HIV screening has traditionally been provided only on request of the inmate, who is frequently reluctant to do so out of fear of the reactions by other inmates and staff, but correctional facilities are increasingly turning to an opt-out approach in which screening is automatic though not mandatory, as the inmate has the option of refusing (43, 71). Correctional facilities still struggle with logistical difficulties such as insufficient protocols or staffing, reluctant administrators, and (in the case of jails) the constant turnover and short stays of many inmates. Even so, a number of facilities work regularly with researchers, with clear implications not only for their own inmates but for public health more generally. A study on syphilis screening in New York, for instance, provided a model for addressing a spike in syphilis rates through jail-based screening and treatment (38), and in Rhode Island, routine HIV testing of all prisoners has led to a diagnosis of one-third of all people known to have HIV in the state (21).

Our knowledge of the systems, extent, and quality of health care in correctional facilities is still impressionistic, but it is clear that despite many improvements since Estelle v. Gamble, the actual delivery of health care remains as uneven as screening. Treatment is consistently provided for only a fraction of those needing it, whether for HIV (15, 89) or HCV (3, 55) or for chronic conditions such as diabetes, mental health, or substance abuse (11, 39, 50). A national profile is complicated by the fact that postintake systems of care vary in prisons and jails, as well as from state to state. Smaller jails rely on arrangements with community-based providers, whereas prisons and large jails (more than 1,000 beds) have their own array of in-house services, sometimes including surgical units. But even in larger systems, it is not always clear who is delivering health care. About 10% of all prisoners are in correctional facilities that are privately owned or operated by for-profit companies, and many of the remaining public facilities have contracted out their health services to private companies or to local academic centers. Although empirical reviews are scant, there is evidence that privatization has both failed to save public money and provided substandard health care (76, 84). Regardless of the system of care, no empirical studies have tracked what happens when an inmate files a request to see a provider (e.g., what percentage of requests are granted and whether they are evenly distributed across demographics). The sporadic evidence that is available suggests that Estelle v. Gamble’s potential for drawing the underserved into care has been left largely unfulfilled, but potential remains for innovative approaches to working with complex cases. For instance, the treatment of HCV with interferon is generally risky owing to its potential to trigger depression or suicide, but the correctional setting could reduce those risks by providing treatment in a closely monitored, secure environment (2).

POSTRELEASE EFFECTS OF INCARCERATION

Each year, more than 600,000 inmates leave prison and more than 7 million leave jail. Because incarceration is not evenly distributed but concentrated in some communities (85), both incarceration and release have enduring health effects on the community as well as the individual. The weeks following release from a correctional facility present extraordinary risks to releasees and others. Former prisoners are 12 times more likely than the general public to die of any cause in the 2 weeks following release and 129 times more likely to die of a drug overdose (14, 75, 77). Some of this postrelease mortality is due to “compassionate release” of the dying (77), but much of it reflects the instability of circumstances in the days following release and the concomitant return to high-risk behaviors (14, 20, 22, 32). Released inmates frequently struggle to find housing and work and to re-establish family and social relations.

Locating housing is the immediate concern of many people leaving prison or jail, an increasing number of whom have been moved to correctional facilities across the state, or even out of state, from their community of origin. Because homelessness and incarceration share similar risk factors, many of the incarcerated were homeless before entering the criminal justice system. Mentally ill inmates were particularly likely to be homeless before their arrest (46). Incarceration in turn increases the odds of being homeless or marginally housed. In one San Francisco study, almost one in four homeless people had been in prison at some point; another study found that 71% of homeless men and 21% of homeless women had been in jail in the past year alone (46, 93). Even though the marginally housed are even less likely to be captured by health surveys than are the incarcerated, the associations between homelessness and/or unemployment and poor health are a longstanding tenet of public health. The drastically reduced odds of finding housing and work contribute to a more complex set of health effects than those described immediately above.

It is thus not surprising that former inmates seeking to stabilize their circumstances often move their health care needs to the back burner. Given the high percentage of former inmates who lack access to affordable health care, release frequently means a sudden halt of treatment and medications (24, 79, 87, 90, 91). Unlike jails, prisons generally offer some form of discharge planning to facilitate continuity of care following release, but many facilities lack the resources to adequately work with a high-needs, low-resource population. In one Texas study, only 5% of HIV-positive releasees filled free Ryan White–funded prescriptions in time to prevent an interruption of treatment (6). Because HIV patients are six times more likely than those with other chronic conditions to identify a regular source of care after discharge (91), non-HIV postrelease continuity of care may be even worse. This is particularly relevant for those with addictions and mental illnesses who received insufficient treatment during incarceration (7, 74), many of whom are incarcerated in the first place because community-based treatment was not accessible.

Few inmates are completely isolated from family and community, and increasing attention is now turning to incarceration’s effects on them. For some, the criminal justice system may represent a reprieve from a family member prone to substance abuse or violence. For other families, incarceration triggers a series of disruptions. In addition to the removal of a support provider, incarceration imposes its own financial strains on families wishing to maintain contact with the incarcerated. Facilities frequently enter into agreements with telephone companies that charge substantially more for collect calls made from the facility, and the location of many newer facilities in rural areas involves significant travel for families based in urban centers (1). Such expenses thus divert family resources from health-related outlays. Previously incarcerated men are also less likely to contribute financially to families with small children (96).

Incarceration affects other relational health mediators as well. In communities witnessing high-density incarceration, the male-female ratio can be so altered as to increase concurrent sexual partnerships—a risk factor for sexually transmitted infection (STI) transmission—and several studies have tracked postrelease HIV and STI transmission (18, 42, 44, 45, 67, 82). Researchers are also addressing the long-term effects of incarceration-triggered relational instability on the children of the incarcerated, who are five times more likely to enter the criminal justice system themselves than are the offspring of the nonincarcerated (28). Particular concerns include the effects on children’s mental health of such factors as the constant surveillance of the formerly incarcerated and their families (19); the possible socialization by prison to solve problems with violence (96); and the psychological effects on children in high-density neighborhoods even when their own parents are not incarcerated, owing to their constant contact with the emotional upheaval of others around them (19). The sons of incarcerated fathers with a history of partner abuse showed decreased aggression associated with paternal incarceration, but boys whose fathers were not known to abuse their mothers exhibited increased aggression with paternal incarceration (96). Concerns over parental incarceration’s effects on children are all the more heightened when the mother, not the father, is the incarcerated parent—a rarer phenomenon, but five times more prevalent among black children whose mothers did not complete high school than among the children of similarly educated white mothers (96).

The most profound effects of high-density incarceration on community health may not be infectious or even mental, but civic and fiscal. Former prisoners and their dependents often remain locked in low socioeconomic status, unemployment, and unstable housing, factors that are consistently associated with low access to health care as well as poor health outcomes. These effects are exacerbated by the social and economic aftermath of entrance into the criminal justice system. In most states, a prison record eliminates eligibility for public assistance such as food stamps, public housing, and student loans. Because most prospective employers ask about previous incarceration on job applications, it becomes nearly impossible to get a job, especially for black men. In the neighborhoods most targeted by law-enforcement surveillance, the result may be a permanent underclass.

At the same time, the geography of criminal justice diverts public resources from those low-income and largely nonwhite communities. The census counts prisoners as residents of the white, nonurban communities where prisons and jails are increasingly relocated. As a result, the public funding and political redistricting that utilize census data for distribution favor the latter over the communities from which prisoners come (33, 61). Finally, the general disenfranchisement of the incarcerated (above all in the 14 states where felons permanently lose the right to vote) weakens the political influence of the community even further, decreasing the chances of public health funding there. Census handling of the incarcerated thus becomes reminiscent of the 3/5 rule, under which slaves were counted as 3/5 of a person to increase slaveholders’ political representation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2001, Nicholas Freudenberg published a cogent overview of the status of research on incarceration and the health of communities, concluding with an agenda for action (28). Ten years later, despite admirable research in the intervening decade, we stand in a discouragingly similar place, one rife, moreover, with ethical pitfalls for the public health practitioner. Rather than containing a distinct subpopulation, the carceral setting might best be viewed as a forum through which public health researchers and practitioners can efficiently reach marginalized communities. But public health researchers and practitioners face a dilemma: By taking advantage of the opportunity to reach the underserved via correctional facilities, they work with a system shown to have adverse effects on individual and community health. The immediate benefits of treatment thus risk lulling medical and public health professionals into overlooking the need to advocate for the preventive measure of a reduction in incarceration.

Next Steps in Public Health Research and Training

Both academic medicine and schools of public health too often allow the next generation of practitioners to complete their training in the purely academic setting. The correctional setting can provide valuable experience in working directly with the medically underserved. In many states, it has been difficult to establish working partnerships with correctional authorities and officials, but precedents do exist for their creation. In criminal justice systems as diverse as San Francisco and Rhode Island, correctional authorities have agreed to work with medical and public health practitioners to expand inmate access to treatment and researchers’ access to understanding this marginalized population.

Medical and public health programs should realize the advantages of correctional-setting training, not only for providing underserved populations with rare access to specialized care but also for the skill sets their own trainees can hone (e.g., the diagnosis of complex comorbidities). All trainees, regardless of the branch of medicine or public health they intend to enter, may garner a greater sense of social responsibility and compassion for those they treat by direct contact with the most marginalized populations and the unique responsibilities this contact entails on the part of the researcher (88). The use of prisons and jails as training sites further allows trainees to be introduced to both the opportunities to reach large numbers of disadvantaged clients and the challenges, in the case of jails, of working with high-turnover populations. Because trainees are likely to meet with correctional and health administrators, correctional officers, and community corrections (i.e., probation and parole), they can also gain critical public health interagency and community training. Thus the opportunities provided by the correctional setting may significantly expand the meaning of the education provided by public health and medical programs.

This expansion is particularly relevant at the intersection of training and research. There have been considerable advances in research in individual conditions over the past ten years. However, researchers and practitioners still tend—very understandably—to focus on single conditions. They now need to develop paradigms for addressing comorbidities, particularly in the medically underserved. For instance, rather than addressing mental illness and HIV separately, albeit with a nod to their frequent overlap, researchers might reconceptualize their approaches to populations with high rates of coexisting conditions. This practice might include research and training at intersections such as the impact of mental illness on HIV care after release from incarceration or the impact of mental illness on the ability of soon-to-be-released prisoners to undergo training in overdose prevention and HIV risk reduction. Whether the paradigm is changed, it must be accompanied by constant attention to the shifting demographics of the incarcerated population. The steep growth trend in Figure 1 has slowed somewhat in recent years, but its overall shape and racial distribution are unlikely to change in the near future. What is changing is the rapid growth of its demographic minorities: older and adolescent inmates, and especially women, who have increased at twice the rate of male prisoners since the 1980s (31). All three groups present distinct health needs, but incarcerated women, with their unmatched acuity levels in almost all health conditions, may be an emerging care and prevention crisis in the criminal justice system.

The real public health research need, though, lies less with specific or even coexisting conditions than with the structures of health care and prevention during and after incarceration. It appears critical to understand better who is delivering care to the incarcerated and how well, which alternatives to incarceration and transitional programs have proved most effective, and which social programs may mitigate the community health effects of both incarceration and reentry.

Next Steps in Public Health Practice

Notwithstanding the treatment and access opportunities provided by criminal justice facilities, public health practitioners would do best to focus their energies on advocacy on two fronts. First, they should use their professional weight to urge the reallocation of public funds to programs that have proved not only to provide access to treatment but also to reduce recidivism:

expanding access to drug courts and mental health courts, or other programs or strategies that divert people from the criminal justice system into community treatment (48, 80);

expanding linkage to care and case management services; and

ensuring that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, once safely ushered through legal challenges, is used as a forum to construct alternative venues of accessing marginalized communities to forestall further reliance on correctional facilities for that access.

Second and more fundamentally, public health practitioners should keep their eyes on the even longer-term agenda. The May 2011 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Plata, which frames health care as a fundamental task of corrections, could tempt stakeholders to perpetuate the criminal justice system’s de facto responsibilities toward many inmates who would, under normal circumstances, be clients of social services agencies. Instead, they should capitalize on Brown v. Plata’s other function: as a warning shot to the correctional-industrial complex. Perhaps the greatest service public health practitioners could provide the incarcerated and their communities is advocacy:

for a drastic reduction of the largely unnecessary incarceration that has resulted from the war on drugs, including dismantling the economic incentives to target minority communities in that war;

for an expansion instead of treatment programs for the mentally ill and the addicted; and

for the recreation of those jobs without which such communities cannot recover.

Without a doubt, incarceration is the best and only option for some people, both for themselves and for the public. But in the past generation, it has become a system that has swallowed a significant number of the mentally ill, the addicted, and many wholly unnecessary targets of a war on drugs run amok, with dire public health consequences.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Rich received funding from the National Institute On Drug Abuse (K24DA022112); the National Institutes of Health, Center for AIDS Research (P30-AI-42853); and the Center for Drug Abuse and AIDS Research (P30DA013868).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Contributor Information

Dora M. Dumont, Email: ddumont1@lifespan.org.

Brad Brockmann, Email: bbrockmann@lifespan.org.

Samuel Dickman, Email: samuel_dickman@hms.harvard.edu.

Nicole Alexander, Email: nalexander2@lifespan.org.

Josiah D. Rich, Email: jrich@lifespan.org.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Alexander M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen SA, Spaulding AC, Osei AM, Taylor LE, Cabral AM, Rich JD. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in a state correctional facility. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:187–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:367–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applebaum PS. Lost in the crowd: prison mental health care, overcrowding, and the courts. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1121–23. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.10.pss6210_1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, Williams BA, Murray OJ. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:103–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301:848–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baillargeon J, Hoge SK, Penn JV. Addressing the challenge of community reentry among released inmates with serious mental illness. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;46:361–75. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baillargeon J, Penn JV, Knight K, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Becker EA. Risk of reincarceration among prisoners with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2010;37:367–74. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baussano I, Williams BG, Nunn P, Beggiato M, Fedeli U, Scano F. Tuberculosis incidence in prisons: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Montague BT, Rich JD. Opportunities to diagnose, treat, and prevent HIV in the criminal justice system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S49–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belenko S, Peugh J. Estimating drug treatment needs among state prison inmates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:269–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:912–19. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binswanger IA, Merrill JO, Krueger PM, White MC, Booth RE, Elmore JG. Gender differences in chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance-dependence disorders among jail inmates. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:476–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binswanger IA, Wortzel HS. Treatment for individuals with HIV/AIDS following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;302:147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.919. author reply 148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce RD, Schleifer RA. Ethical and human rights imperatives to ensure medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence in prisons and pre-trial detention. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. JAMA. 2009;301:183–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Pendo M, Loughran E, Estes M, Katz M. Highly active antiretroviral therapy use and HIV transmission risk behaviors among individuals who are HIV infected and were recently released from jail. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:661–66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comfort M. Punishment beyond the legal offender. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci. 2007;3:271–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daniels J, Crum M, Ramaswamy M, Freudenberg N. Creating REAL MEN: description of an intervention to reduce drug use, HIV risk, and rearrest among young men returning to urban communities from jail. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12:44–54. doi: 10.1177/1524839909331910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai AA, Latta ET, Spaulding A, Rich JD, Flanigan TP. The importance of routine HIV testing in the incarcerated population: the Rhode Island experience. AIDS Ed Prev. 2002;14:45–52. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.7.45.23867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolan KA, Shearer J, White B, Zhou J, Kaldor J, Wodak AD. Four-year follow-up of imprisoned male heroin users and methadone treatment: mortality, re-incarceration and hepatitis C infection. Addiction. 2005;100:820–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domino ME, Norton EC, Morrissey JP, Thakur N. Cost shifting to jails after a change to managed mental health care. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1379–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Draine J, Ahuja D, Altice FL, Arriola KJ, Avery AK, et al. Strategies to enhance linkages between care for HIV/AIDS in jail and community settings. AIDS Care. 2011;23:366–77. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet. 2011;377:956–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 23000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet. 2002;359:545–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiscella K, Pless N, Meldrum S, Fiscella P. Alcohol and opiate withdrawal in US jails. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1522–24. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health. 2001;78:214–35. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freudenberg N. Adverse effects of US jail and prison policies on the health and well-being of women of color. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1895–99. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freudenberg N. HIV in the epicenter of the epicenter: HIV and drug use among criminal justice populations in New York City, 1980–2007. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:159–70. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1725–36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freudenberg N, Ramaswamy M, Daniels J, Crum M, Ompad DC, Vlahov D. Reducing drug use, human immunodeficiency virus risk, and recidivism among young men leaving jail: evaluation of the REAL MEN re-entry program. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:448–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golembeski C, Fullilove R. Criminal (in)justice in the city and its associated health consequences. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:S185–90. doi: 10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: findings at 6 months post-release. Addiction. 2008;103:1333–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.002238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases among correctional inmates: transmission, burden, and an appropriate response. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:974–78. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haney C. Mental health issues in long-term solitary and “supermax” confinement. Crime Delinq. 2003;49:124–56. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatcher SS, Toldson IA, Godette DC, Richardson JB., Jr Mental health, substance abuse, and HIV disparities in correctional settings: practice and policy implications for African Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:6–16. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heimberger TS, Chang HG, Birkhead GS, DiFerdinando GD, Greenberg AJ, et al. High prevalence of syphilis detected through a jail screening program. A potential public health measure to address the syphilis epidemic. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1799–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henderson CE, Taxman FS. Competing values among criminal justice administrators: the importance of substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103(Suppl 1):S7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iguchi MY, Bell J, Ramchand RN, Fain T. How criminal system racial disparities may translate into health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:48–56. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Washington, DC: U.S. Dep. Justice, Bur. Justice Stat; 2006. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=789. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson R, Raphael S. The effects of male incarceration dynamics on acquired immune deficiency syndrome infection rates among African American women and men. J Law Econ. 2009;52:251–93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kavasery R, Maru DS, Sylla LN, Smith D, Altice FL. A prospective controlled trial of routine opt-out HIV testing in a men’s jail. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan MR, Epperson MW, Mateu-Gelabert P, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Friedman SR. Incarceration, sex with an STI- or HIV-infected partner, and infection with an STI or HIV in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY: a social network perspective. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1110–17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, Adimora AA, Moseley C, et al. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. J Urban Health. 2008;85:100–13. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kushel MB, Hahn JA, Evans JL, Bangsberg DR, Moss AR. Revolving doors: imprisonment among the homeless and marginally housed population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1747–52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. The shift of psychiatric inpatient care from hospitals to jails and prisons. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:529–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. Mental health courts as a way to provide treatment to violent persons with severe mental illness. JAMA. 2008;300:722–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Gross BH. Mentally ill persons in the criminal justice system: some perspectives. Psychiatr Q. 2004;75:107–26. doi: 10.1023/b:psaq.0000019753.63627.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larney S. Does opioid substitution treatment in prisons reduce injecting-related HIV risk behaviours? A systematic review. Addiction. 2010;105:216–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis C. Treating incarcerated women: gender matters. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29:773–89. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macalino GE, Vlahov D, Sanford-Colby S, Patel S, Sabin K, et al. Prevalence and incidence of HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infections among males in Rhode Island prisons. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1218–23. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacNeil JR, Lobato MN, Moore M. An unanswered health disparity: tuberculosis among correctional inmates, 1993 through 2003. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1800–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magura S, Lee JD, Hershberger J, Joseph H, Marsch L, et al. Buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in jail and post-release: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin CK, Hostetter JE, Hagan JJ. New opportunities for the management and therapy of hepatitis C in correctional settings. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:13–17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maruschak LM. HIV in Prisons, 2007–08. Washington, DC: U.S. Dep. Justice, Bur. Justice Stat. Rep; 2009. NCJ 228307. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massoglia M. Incarceration as exposure: the prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49:56–71. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Massoglia M. Incarceration, health, and racial disparities in health. Law Soc Rev. 2008;42:275–306. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McClelland GM, Teplin LA, Abram KM, Jacobs N. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors among female jail detainees: implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:818–25. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McMillan GP, Lapham S, Lackey M. The effect of a jail methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) program on inmate recidivism. Addiction. 2008;103:2017–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore LD, Elkavich A. Who’s using and who’s doing time: incarceration, the war on drugs, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:782–86. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nunn A, Zaller N, Dickman S, Trimbur C, Nijhawan A, Rich JD. Methadone and buprenorphine prescribing and referral practices in US prison systems: results from a nationwide survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patterson E. Incarcerating death: mortality in US state correctional facilities, 1985–1998. Demography. 2010;47(3):587–607. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pew Cent. States. One in 100: Behind Bars in America 2008. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts; 2008. http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/report_detail.aspx?id=35904. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pew Cent. States. One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts; 2009. http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/report_detail.aspx?id=49382. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pinkerton SD, Galletly CL, Seal DW. Model-based estimates of HIV acquisition due to prison rape. Prison J. 2007;87:295–310. doi: 10.1177/0032885507304525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Blankenship KM. Associations of sex ratios and male incarceration rates with multiple opposite-sex partners: potential social determinants of HIV/STI transmission. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):70–80. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Raimer BG, Stobo JD. Health care delivery in the Texas prison system: the role of academic medicine. JAMA. 2004;292:485–89. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rhodes LA. Pathological effects of the supermaximum prison. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1692–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rich JD, Boutwell AE, Shield DC, Key RG, McKenzie M, et al. Attitudes and practices regarding the use of methadone in US state and federal prisons. J Urban Health. 2005;82:411–19. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA, White BL, Stewart PW, Golin CE. An evaluation of HIV testing among inmates in the North Carolina prison system. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S452–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA, White BL, Stewart PW, Golin CE. Characteristics and behaviors associated with HIV infection among inmates in the North Carolina prison system. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1123–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosen DL, Wohl DA, Schoenbach VJ. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among black and white North Carolina state prisoners, 1995–2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:719–26. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scheyett A, Parker S, Golin C, White B, Davis CP, Wohl D. HIV-infected prison inmates: depression and implications for release back to communities. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:300–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9443-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seaman SR, Brettle RP, Gore SM. Mortality from overdose among injecting drug users recently released from prison: database linkage study. BMJ. 1998;316:426–28. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shalev N. From public to private care: the historical trajectory of medical services in a New York city jail. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:988–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK. Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: implications for health-care planning. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:479–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Springer SA, Azar MM, Altice FL. HIV, alcohol dependence, and the criminal justice system: a review and call for evidence-based treatment for released prisoners. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:12–21. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.540280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steadman HJ, Redlich A, Callahan L, Robbins PC, Vesselinov R. Effect of mental health courts on arrests and jail days: a multisite study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:167–72. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Subst. Abuse Ment. Health Serv. Adm. Summary of National Findings. I. Rockville, MD: Off. Appl. Stud; 2010. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Ser. H-38A, HHS Publ. No. SMA 10-4856 Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thomas JC, Levandowski BA, Isler MR, Torrone E, Wilson G. Incarceration and sexually transmitted infections: a neighborhood perspective. J Urban Health. 2008;85:90–99. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Handbook on Prisoners with Special Needs. New York: United Nations; 2009. http://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/Prisoners-with-special-needs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 84.von Zielbauer P. New York Times. 2005. Feb 27, As health care in jails goes private, 10 days can be a death sentence; p. A1.p. A32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wacquant L. Class, race and hyperincarceration in revanchist America. Daedalus. 2010;139(3):74–90. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wacquant L. Deadly symbiosis: when ghetto and prison meet and mesh. Punishm Soc. 2001;3(1):95–133. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wakeman SE, McKinney ME, Rich JD. Filling the gap: the importance of Medicaid continuity for former inmates. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:860–62. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0977-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wakeman SE, Rich JD. Fulfilling the mission of academic medicine: training residents in the health needs of prisoners. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):S186–88. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1258-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wakeman SE, Rich JD. HIV treatment in US prisons. HIV Ther. 2010;4:505–10. doi: 10.2217/hiv.10.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang EA, Hong CS, Samuels L, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kushel M. Transitions clinic: creating a community-based model of health care for recently released California prisoners. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:171–77. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang EA, White MC, Jamison R, Goldenson J, Estes M, Tulsky JP. Discharge planning and continuity of health care: findings from the San Francisco County Jail. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:2182–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Warren E, Viney R, Shearer J, Shanahan M, Wodak A, Dolan K. Value for money in drug treatment: economic evaluation of prison methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:160–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weiser SD, Neilands TB, Comfort ML, Dilworth SE, Cohen J, et al. Gender-specific correlates of incarceration among marginally housed individuals in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1459–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weiss JJ, Osorio G, Ryan E, Marcus SM, Fishbein DA. Prevalence and patient awareness of medical comorbidities in an urban AIDS clinic. AIDS Pat Care. 2010;24(1):39–48. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wildeman C. Invited commentary: (mass) imprisonment and (inequities in) health. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(5):488–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wildeman C, Western B. Incarceration in fragile families. Future Child. 2010;20:157–77. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, Lasser KE, McCormick D, et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:666–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]