Abstract

Heart development is a complex process that involves cell specification and differentiation, as well as elaborate tissue morphogenesis and remodeling, to generate a functional organ. The zebrafish has emerged as a powerful model system to unravel the basic genetic, molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac development and function. Here we summarize and discuss recent discoveries on early cardiac specification and the identification of the second heart field in zebrafish. In addition to the inductive signals regulating cardiac specification, these studies have shown that heart development also requires a repressive mechanism imposed by retinoic acid signaling to select cardiac progenitors from a multipotent population. Another recent advance in the study of early zebrafish cardiac development is the identification of the second heart field (SHF). These studies suggest that the molecular mechanisms that regulate SHF development are conserved between zebrafish and other vertebrates including mammals, and provide insight into the evolution of the SHF and its derivatives.

Keywords: retinoid acid signaling, Fgf signaling, second heart field, Ltbp3, zebrafish

Introduction and advantages of the zebrafish system

Cardiac diseases remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, and many of these diseases arise at least in part from genetic defects that impact the development and maturation of the heart. Therefore, understanding the genetic, molecular and cellular mechanisms that govern the formation, differentiation, and growth of the heart will greatly enhance our understanding of heart disease, and facilitate the identification of new approaches to repair or regenerate damaged heart muscle 1–4.

With the development of various genetic and cell biological tools including forward genetic screens, transgenesis, lineage tracing and cell transplantation, the zebrafish has emerged as a powerful vertebrate model organism to investigate a number of biological processes. In addition, the zebrafish offers several distinct advantages as a model to study cardiac development. First, the external development of the embryos allows a direct noninvasive observation of the development of the heart as it happens and at cellular resolution5. Second, zebrafish embryos do not initially rely on their cardiovascular system for oxygen needs. Therefore, zebrafish cardiac mutants can survive and continue to develop for several days, allowing a detailed analysis of their phenotype. Although the zebrafish heart is simpler in structure than its mammalian counterpart, genes responsible for essential steps of cardiac development are conserved throughout vertebrates. Thus, studies of cardiac development using the zebrafish as a model organism will continue to help address key questions in cardiac development. This review is not intended to cover every aspect of cardiac development in zebrafish, but rather focuses on cardiac progenitor specification as well as the recent discovery of the second heart field in zebrafish.

Early cardiac specification in zebrafish

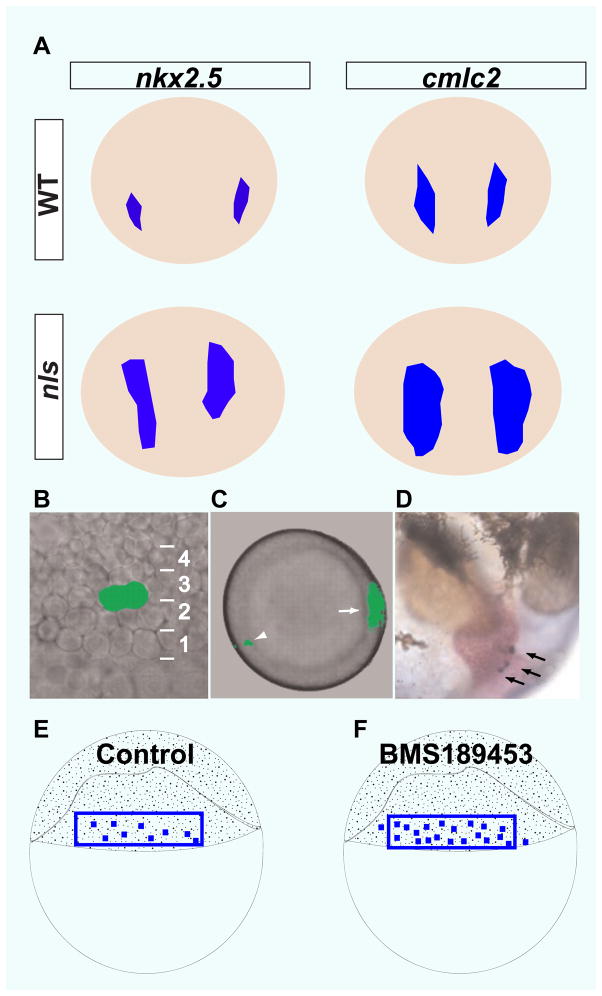

A fundamental question in organogenesis concerns the means by which the organ progenitor cells are specified. Previous studies in Xenopus, chick and mouse have implicated several signaling molecules, such as Bmp, Activin/Nodal, Fgfs and Wnts as positive regulators of this process6–10. Although it is conceivable that the combinatorial action of these signaling molecules could delineate the correct number of cardiac progenitors, it was not known whether a repressive mechanism was also involved. Using a combination of genetic, pharmacological and fate mapping approaches, Keegan et al., showed that in zebrafish the potential of naïve cells to adopt a cardiogenic fate is restricted by retinoid acid (RA) signaling11. aldh1a2 (aka neckless) mutants, which are defective in RA synthesis, generate an excess number of cardiomyocytes. A similar cardiomyocyte expansion phenotype is also observed in embryos treated with the pan-RA receptor antagonist BMS189453 before and during gastrulation. To define the role of RA signaling in cardiac specification more precisely, the authors generated a high-resolution fate map of the lateral marginal zone of the late blastula11, 12, the region where the cardiac progenitors are located13. They showed that twice as many cells from this region of the embryo become cardiomyocytes in BMS189453-treated animals than in controls, suggesting that the generation of extra cardiomyocytes in RA-deficient embryos results from fate transformation rather than increased cardiomyocyte proliferation. A closer examination of the role of RA signaling in cardiac specification revealed that the number of cells in both the atrial and ventricular chambers was significantly increased upon BMS treatment during gastrulation14. Additional fate mapping experiments showed that the increase in the number of ventricular cardiomyocytes was due to an increased number of ventricular progenitors. In contrast, BMS treatment did not generate more atrial progenitors but rather allowed each atrial progenitor to produce more progeny. RA signaling also appears to restrict atrial cell numbers over a longer time window. BMS treatment around 6–8 somite stage still increased the number of atrial but not ventricular cells. This restriction of atrial cells by RA signaling at early somite stages appears to be mediated by hoxb5b, a hox gene whose expression in the adjacent forelimb field is induced by RA signaling14. In hoxb5b morphants, the atrium is enlarged and the number of atrial, but not ventricular, cells is increased14. Thus, Hoxb5b appears to act in a cell non-autonomous fashion to restrict atrial but not ventricular fate, although the exact nature of the forelimb-derived Hoxb5b-dependent signal(s) remains to be identified. Given this specific effect of Hoxb5b on atrial cell fate, it may also be necessary to invoke an independent factor(s) that mediates the repressive effect of RA signaling on ventricular cell fate. In this regard, future studies designed to identify this factor(s) will certainly provide a more comprehensive picture of how RA signaling exerts it inhibitory effect on cardiomyocyte fate. Besides Hox5b, Fgf (Fibroblast growth factor ) signaling also appears to act downstream of RA signaling to regulate both heart and forelimb formation15. Enhancing Fgf signaling by global overexpression of a constitutive version of Fgfr1 at the end of gastrulation phenocopied the loss of RA signaling. More importantly, both the cardiac and forelimb defects caused by RA deficiency could be rescued by morpholino knockdown of fgf8, suggesting that RA signaling acts to temper Fgf signaling to ensure the proper development of both the heart and forelimb. In line with these findings in zebrafish, previous studies in mouse have revealed a similar role for RA signaling in reducing Fgf signaling to restrict the specification of cardiac progenitors16, 17.

Second heart field in zebrafish

A recent advance in cardiac biology has come from the identification of two sources of cardiac progenitors in chick and mouse embryos. The first heart field (FHF) contributes mainly to the linear heart tube. Cells from the second heart field (SHF) are then recruited to the heart tube, contributing to its further growth and elaboration into a functional pumping organ18. The discovery of the SHF dates back to 1977 when de la Cruz showed that the formation of the cardiac outflow tract in chick embryos involved the recruitment of cells from a progenitor population located in the pharyngeal mesoderm19, which was later referred to as the anterior or secondary heart field. The identification of an analogous population in mouse was facilitated by a lacZ transgene inserted in the Fgf10 (Fibroblast growth factor 10) locus20, 21. Cells expressing this transgene are initially located in the pharyngeal mesoderm, and later become incorporated into the arterial pole of the heart. The SHF also contains the region immediately posterior to the Fgf10-LacZ expression domain22. This posterior portion of the SHF contributes to the venous pole of the heart. The entire SHF expresses the homeobox gene Islet-1 (Isl1), a critical regulator of SHF development. In the absence of Isl1 function, SHF derivatives such as the right ventricle and outflow tract fail to form 22. Despite its primitive outflow tract and lack of a right ventricle, the zebrafish heart does require a SHF for the formation of its arterial pole23–26. Studies of zebrafish SHF development suggest that the molecular mechanisms underlying this process are largely conserved with those in other vertebrates including mammals. These studies also identified new regulators of SHF development and provided novel insights into this process.

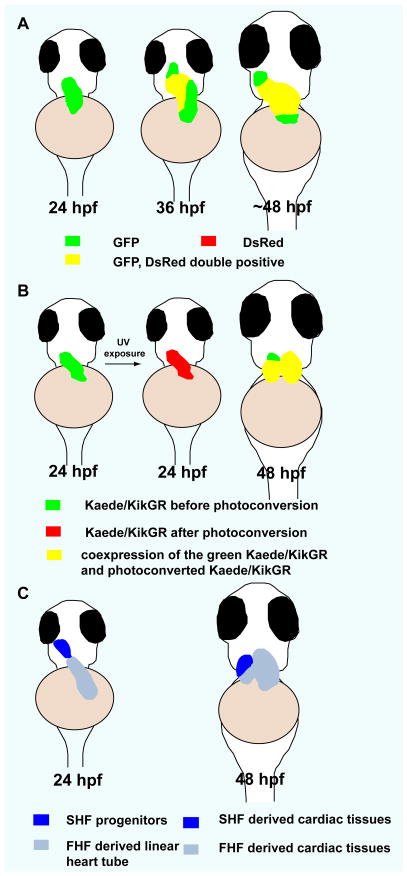

The ability to perform high-resolution live imaging in zebrafish allowed direct visualization of the addition of late cardiogenic cells to the growing heart tube. Taking advantage of the slower maturation and fluorescence properties of DsRed compared to eGFP27, 28, de Pater et al., examined the temporal order of cardiomyocyte differentiation23. With this assay, two cardiomyocyte populations were observed in the developing heart: the early differentiated eGFP and DsRed double positive cells and the newly differentiated eGFP positive and DsRed negative cells. The analysis of the distribution of these two populations at different time points, as well as Kaede photoconversion experiments, suggested two distinct phases of cardiomyocyte differentiation23, 25. The linear heart tube was formed as the result of the first round of progressive cardiomyocyte differentiation, whereas the second round of cardiomyocyte differentiation gave rise to the myocardium of the arterial pole of the heart. At the linear heart tube stage and prior to its differentiation, this late cardiogenic population seems to be located at the extra-cardiac region that lies immediately adjacent to the arterial pole of the heart, and it appears to express the MADS box transcription factor gene mef2cb and activate the Fgf signaling pathway23, 25.

Consistent with their expression/activation pattern and role in mouse arterial pole development, Mef2cb and Fgf signaling are both required for late cardiomyocyte addition to the arterial pole in zebrafish23, 25. The development of the arterial pole in zebrafish also appears to be dependent on Shh signaling and the T-box transcription factor Tbx1, two other key regulators of mouse arterial pole development24, 29–31. In the absence of Shh signaling or Tbx1 function, the ventricle and outflow tract of the zebrafish heart become significantly reduced in size due to a reduction in the incorporation of late cardiogenic cells to the arterial pole24. Thus, the analogous position of the late cardiogenic population relative to the linear heart tube, as well as the observation that the same genes regulate the addition of its derived cells to the arterial pole, strongly support the notion that the late cardiogenic population in zebrafish shares characteristics with the SHF of other vertebrates including mammals.

Although the aforementioned studies clearly revealed the existence of a SHF in zebrafish, the extent to which it contributed to heart formation remained unresolved. For instance, a previous study had suggested that the arterial pole of the zebrafish heart gives rise to the distal part of the ventricle and the outflow tract32. In support of this idea, DiI labeling experiments showed that cells located in the dorsal pericardial wall adjacent to the arterial pole at the linear heart tube stage indeed contributed to the distal portion of the ventricular myocardium24. But how much of the ventricular myocardium derived from the SHF remained unclear. A recent study has implicated the latent Tgfβ binding protein 3 (Ltbp3), a regulator of Tgfβ secretion and activation, in arterial pole development in zebrafish26. Genetic tracing experiments revealed that the ltbp3 expressing cells, which are originally located immediately adjacent to the linear heart tube, contribute significantly to the developing heart, making up the distal half of the ventricular myocardium as well as the myocardium of the proximal outflow tract. The ltbp3 positive cells also give rise to the endothelial and smooth muscle cells of the outflow tract. In addition, it appears that Ltbp3 is specifically required for the formation of the cardiac structures that derive from the ltbp3 expressing cells. Morpholino knockdown of ltbp3 caused severe ventricular defects with a nearly fifty percent reduction of the number of ventricular cardiomyocytes and endocardial cells, whereas the development of the atrium was not affected. ltbp3 morphants also failed to form the outflow tract smooth muscle cells. Although the molecular mechanisms by which Ltbp3 regulates SHF development remian unclear, the SHF progenitors in ltbp3 morphants are specified properly, but they fail to proliferate or self-renew to replenish the progenitor pool as they differentiate and migrate into the heart. Consistent with a role for Ltbp3 in regulating Tgfβ signaling, embryos treated with a pharmacological inhibitor of Tgfβ signaling recapitulated the ltbp3 morphant phenotypes, thereby for the first time implicating Tgfβ signaling in controlling the proliferation or renewal of the SHF progenitors during arterial pole development.

Although roles for Fgf signaling, Tbx1 and Mef2c have been clearly established in zebrafish SHF development, the specific aspects of SHF development regulated by these factors remain to be determined. For instance, we need to understand whether these signaling pathways and transcription factors regulate the specification, proliferation, differentiation, or survival of SHF cells or simply the addition of the SHF cells to the heart tube. In addition, it will also be important to investigate how the different signaling pathways and transcription factors interact to coordinate the specification, proliferation, differentiation and migratory behaviors of the SHF progenitors.

The identification of a SHF in zebrafish has important implications for understanding congenital heart disease. Defects in SHF development, such as mis-specification of the SHF progenitors or the failure of the addition of SHF cells to the heart tube, often lead to congenital heart disease. As a genetically tractable system, zebrafish offers unique advantages to study SHF development as the transparency of the embryos allows a detailed study of cell behaviors in wildtype and mutant animals.

Evolutionary implications of the identification of a SHF in zebrafish

During the transition from aquatic to terrestrial life, vertebrate hearts acquired a new set of cardiac components to separate the systemic and pulmonary circulations. The newly aquired cardiac segments for pulmonary circulation, such as the right ventricle are mostly derived from the SHF33, 34. Thus, the identification of a SHF in zebrafish, an organism that does not have a separate pulmonary circulation has important evolutionary implications, and argues against the idea that the SHF and the pulmonary circulation co-evolved in terrestrial vertebrates. Interestingly, the zebrafish ventricle and the primitive ventricle of “higher” vertebrates appear to be patterned in a similar fashion. In both cases, SHF derived cells contribute to the formation of a distinct segment of the ventricle26.

Although many of the molecular mechanisms that regulate the development of the SHF and its derivatives are conserved between zebrafish and higher vertebrates, it is worth noting that Islet-1, a key regulator of mouse SHF development, does not appear to be required for arterial pole formation in zebrafish23. Cardiomyocyte differentiation at the venous pole, however, was affected by the loss of Islet-1 function. In zebrafish islet-1 mutants, bmp4 expression at the venous pole is completely absent whereas its expression at the atrioventricular junction and outflow tract is not affected23. While zebrafish Islet-1 is thus more confined to regulate venous pole cardiomyocyte differentiation, mouse Islet-1 is required for controlling the development of both arterial and venous poles22. This broader function of mouse Islet-1 is likely due to the fact that in mouse, the arterial and venous poles are both closely apposed to Islet-1 expressing pharyngeal mesoderm. In zebrafish, however, the Islet-1 positive cells in the cardiac field are not in close contact with the future arterial pole23. Thus, one could speculate that Islet-1 expanded its expression domain and gained a new function in controlling the development of the arterial pole as the terrestrial vertebrates emerged. Alternatively, and in light of a recent study in Ciona35, it is also possible that zebrafish lost the islet-1 expression pattern that allows it to regulate arterial pole development.

Fig 1.

RA signaling restricts cardiogenic potential. A) nkx2.5 and cmlc2 expression domains are expanded in aldh1a2 (aka neckless) mutant embryos compared to wildtype (6-somite stage for nkx2.5 expression and 16-somite stage for cmlc2 expression). Dorsal views, anterior to the top. B–D) Construction of blastomere fate map with caged fluorescein. B) Lateral view of two neighboring blastomeres (40% epiboly stage) in tier 3 that were labeled by activating caged fluorescein. C) Animal pole view of labeled blastomeres (arrowhead). The dorsal midline was labeled by Tg(gsc:GFP) expression (arrow). D) Descendants of the labeled blastomeres were identified in the heart (arrows, 44 hpf (hours post-fertilization)). (E–F) Schematics illustrate that more blastomeres have cardiogenic potential in BMS189453-treated embryos than in control (40% epiboly blastula stage). (adapted from Keegan BR et al., Science. 307:207–209).

Fig 2.

Second heart field in zebrafish. A) Temporal order of cardiomyocyte differentiation: newly differentiated cardiomyocytes (green), earlier differentiated cardiomyocytes (yellow). B) Kaede/kikGR photoconversion experiments suggest that cardiomyocytes at the arterial pole of the zebrafish heart differentiate after the formation of the linear heart tube (green). C) Contribution of the SHF to zebrafish heart development. At 24 hpf, SHF progenitors are located immediately adjacent to the ventricle. At 48 hpf, SHF derived cells populate the distal segment of the ventricle as well as the outflow tract. Ventral views, anterior to the top. (adapted from de Pater E et al., Development. 136:1633–1641, Lazic and Scott, Developmental biology. 354:123–133, and Zhou Y et al., Nature. 474:645–648)

Acknowledgments

We thank Rima Arnaout and David Staudt for critical reading of the manuscript. J.L. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association and an NIH (National Institutes of Health) training grant (Principle investigator: Shaun R. Coughlin, T32 HL007731) and is currently supported by an NIH Pathway to Independence (PI) Award (K99 HL109079). Work in our laboratory is funded by grants to D.Y.R.S. from the NIH (HL054737) as well as the Packard foundation.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- RA

Retinoid Acid

- Fgf

Fibroblast growth factor

- LPM

lateral plate mesoderm

- SHF

second heart field

- Mef2ca

Myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2C

- Tbx

T-box

- Ltbp3

latent Tgfβ binding protein 3

- hpf

hours post-fertilization

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Chien KR. Lost and found: cardiac stem cell therapy revisited. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:1838–1840. doi: 10.1172/JCI29050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, Gruber P, Chen Y, Woodard S, Lin LZ, Cai CL, Lu MM, Reth M, Platoshyn O, Yuan JX, Evans S, Chien KR. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature. 2005;433:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nature03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olson EN. A genetic blueprint for growth and development of the heart. Harvey lectures. 2002;98:41–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson EN, Schneider MD. Sizing up the heart: development redux in disease. Genes & development. 2003;17:1937–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beis D, Stainier DY. In vivo cell biology: following the zebrafish trend. Trends in cell biology. 2006;16:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultheiss TM, Burch JB, Lassar AB. A role for bone morphogenetic proteins in the induction of cardiac myogenesis. Genes & development. 1997;11:451–462. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marvin MJ, Di Rocco G, Gardiner A, Bush SM, Lassar AB. Inhibition of Wnt activity induces heart formation from posterior mesoderm. Genes & development. 2001;15:316–327. doi: 10.1101/gad.855501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider VA, Mercola M. Wnt antagonism initiates cardiogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Genes & development. 2001;15:304–315. doi: 10.1101/gad.855601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsan BH, Schultheiss TM. Regulation of avian cardiogenesis by Fgf8 signaling. Development (Cambridge, England) 2002;129:1935–1943. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiter JF, Verkade H, Stainier DY. Bmp2b and Oep promote early myocardial differentiation through their regulation of gata5. Developmental biology. 2001;234:330–338. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keegan BR, Feldman JL, Begemann G, Ingham PW, Yelon D. Retinoic acid signaling restricts the cardiac progenitor pool. Science (New York, NY) 2005;307:247–249. doi: 10.1126/science.1101573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keegan BR, Meyer D, Yelon D. Organization of cardiac chamber progenitors in the zebrafish blastula. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131:3081–3091. doi: 10.1242/dev.01185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stainier DY, Lee RK, Fishman MC. Cardiovascular development in the zebrafish. I. Myocardial fate map and heart tube formation. Development (Cambridge, England) 1993;119:31–40. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waxman JS, Keegan BR, Roberts RW, Poss KD, Yelon D. Hoxb5b acts downstream of retinoic acid signaling in the forelimb field to restrict heart field potential in zebrafish. Developmental cell. 2008;15:923–934. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorrell MR, Waxman JS. Restraint of Fgf8 signaling by retinoic acid signaling is required for proper heart and forelimb formation. Developmental biology. 2011;358:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirbu IO, Zhao X, Duester G. Retinoic acid controls heart anteroposterior patterning by down-regulating Isl1 through the Fgf8 pathway. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1627–1635. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SC, Dolle P, Ryckebusch L, Noseda M, Zaffran S, Schneider MD, Niederreither K. Endogenous retinoic acid regulates cardiac progenitor differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9234–9239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910430107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckingham M, Meilhac S, Zaffran S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nature reviews. 2005;6:826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrg1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de la Cruz MV, Sanchez Gomez C, Arteaga MM, Arguello C. Experimental study of the development of the truncus and the conus in the chick embryo. Journal of anatomy. 1977;123:661–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly RG, Brown NA, Buckingham ME. The arterial pole of the mouse heart forms from Fgf10-expressing cells in pharyngeal mesoderm. Developmental cell. 2001;1:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly RG, Buckingham ME. The anterior heart-forming field: voyage to the arterial pole of the heart. Trends Genet. 2002;18:210–216. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Developmental cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Pater E, Clijsters L, Marques SR, Lin YF, Garavito-Aguilar ZV, Yelon D, Bakkers J. Distinct phases of cardiomyocyte differentiation regulate growth of the zebrafish heart. Development (Cambridge, England) 2009;136:1633–1641. doi: 10.1242/dev.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hami D, Grimes AC, Tsai HJ, Kirby ML. Zebrafish cardiac development requires a conserved secondary heart field. Development (Cambridge, England) 2011;138:2389–2398. doi: 10.1242/dev.061473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazic S, Scott IC. Mef2cb regulates late myocardial cell addition from a second heart field-like population of progenitors in zebrafish. Developmental biology. 2011;354:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Cashman TJ, Nevis KR, Obregon P, Carney SA, Liu Y, Gu A, Mosimann C, Sondalle S, Peterson RE, Heideman W, Burns CE, Burns CG. Latent TGF-beta binding protein 3 identifies a second heart field in zebrafish. Nature. 2011;474:645–648. doi: 10.1038/nature10094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verkhusha VV, Kuznetsova IM, Stepanenko OV, Zaraisky AG, Shavlovsky MM, Turoverov KK, Uversky VN. High stability of Discosoma DsRed as compared to Aequorea EGFP. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7879–7884. doi: 10.1021/bi034555t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verkhusha VV, Otsuna H, Awasaki T, Oda H, Tsukita S, Ito K. An enhanced mutant of red fluorescent protein DsRed for double labeling and developmental timer of neural fiber bundle formation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:29621–29624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyer LA, Kirby ML. Sonic hedgehog maintains proliferation in secondary heart field progenitors and is required for normal arterial pole formation. Developmental biology. 2009;330:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H, Morishima M, Wylie JN, Schwartz RJ, Bruneau BG, Lindsay EA, Baldini A. Tbx1 has a dual role in the morphogenesis of the cardiac outflow tract. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131:3217–3227. doi: 10.1242/dev.01174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Washington Smoak I, Byrd NA, Abu-Issa R, Goddeeris MM, Anderson R, Morris J, Yamamura K, Klingensmith J, Meyers EN. Sonic hedgehog is required for cardiac outflow tract and neural crest cell development. Developmental biology. 2005;283:357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimes AC, Kirby ML. The outflow tract of the heart in fishes: anatomy, genes and evolution. Journal of fish biology. 2009;74:983–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farmer CG. Evolution of the vertebrate cardio-pulmonary system. Annual review of physiology. 1999;61:573–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hillenius WJ, Ruben JA. The evolution of endothermy in terrestrial vertebrates: Who? When? Why? Physiol Biochem Zool. 2004;77:1019–1042. doi: 10.1086/425185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolfi A, Gainous TB, Young JJ, Mori A, Levine M, Christiaen L. Early chordate origins of the vertebrate second heart field. Science (New York, NY) 2010;329:565–568. doi: 10.1126/science.1190181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]