Abstract

Objective

Using published data, we sought to determine the amniocentesis-related loss rate in twin gestations.

Methods

We searched the PUBMED database using keywords “amniocentesis”, “twin” and “twins” to identify articles evaluating genetic amniocentesis in twin gestations published from January 1970 to December 2010. Random effects models were used to pool procedure-related loss rates from included studies.

Results

The definition of “loss” varied across the 17 studies identified (Table 1). The pooled procedure-related loss rate at < 24 weeks was 3.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.6-4.7) (Figure 2). Pooled loss rates at < 28 weeks (Figure 4) and to term (Figure 5) could not be calculated due to unacceptable heterogeneity of available data. Seven studies included a control (no amniocentesis) group and reported a pooled odds ratio for total pregnancy loss among cases of 1.8 (95% CI 1.2-2.7) (Figure 3). Only 1 study reported procedure-related loss rates by chorionicity (7.7% among monochorionics vs 1.4% among controls; p 0.02).

Conclusion

Analysis of published data demonstrated a pooled amniocentesis-related loss rate of 3.5% in twin gestations < 24 weeks. Pooled loss rates within other post-amniocentesis intervals or other gestational age windows and the impact of chorionicity on procedure-related loss rates cannot be determined from published data.

Keywords: twin, amniocentesis, loss rate

Introduction

In the United States, the number of multiple pregnancies has exponentially increased in the last several decades. From 1980 to 2001, twin pregnancies rose by 77 percent (Martin et al, 2002) and in 2005, the twin birth rate in the US was 32.2 per 1000 live births (Martin et al, 2008). This increase is thought to be due to delayed childbearing and the expanded use of assisted reproductive techniques. As Martin et al reported, from 1990 to 2002, the birth rate in women aged 35-39 increased 31 percent (Martin et al, 2002) and Blondel et al (2002) also noted that in countries with high rates of multiple births, 30-50 percent of twin pregnancies occur after infertility treatment.

While the risk of chromosomal abnormalities increases with advancing maternal age, it has also been reported that there is an increased risk of structural and chromosomal abnormalities in twins compared to singleton gestations (Wapner et al, 1993). The need and demand for prenatal diagnosis of fetal genetic disorders in twin gestations is therefore not uncommon and will likely increase in the future.

Genetic amniocentesis is a procedure generally offered between 15-20 weeks gestation. When counseling and consenting a patient for an amniocentesis, one complication that must be mentioned is the risk of “procedure-related loss”. For a singleton pregnancy, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin cites a procedure-related loss rate of 1/300 to 1/500 (ACOG, 2007). A number of studies have investigated the loss rate after an amniocentesis in twin gestations. However, similar to singleton pregnancies, the exact procedure-related loss rate has been elusive due to several factors including varying definitions of “pregnancy loss”, the underestimation of fetal loss because of elective pregnancy termination due to abnormal karyotype in the amniocentesis group, the natural loss rate due to maternal age and other maternal factors (abnormal serum screening results, past history of miscarriage, vaginal bleeding) and the natural increased loss rate in twins vs singletons. When managing twin gestations, there is also the added factor of chorionicity and monochorionic twins have a higher spontaneous loss rate than dichorionic twin gestations (Sperling et al, 2006).

This study sought to systematically review the available literature on amniocentesis and to establish a pooled loss rate that could be used in counseling patients considering genetic amniocentesis in twin gestations. In addition, we also sought to determine if prior studies have stratified results by chorionicity, and if the procedure-related loss rate among monochorionic twin gestations differs from dichorionic twin gestations.

Source

We performed a PUBMED database search using key words “amniocentesis”, “twin” and “twins” from January 1, 1970 to December 31, 2010. All abstracts were reviewed by the first and second authors. All abstracts reporting loss rates after amniocentesis in twin pregnancies were identified and the manuscripts were retrieved as a hard copy for in-depth analysis by the same two authors. References for the retrieved articles were also examined in search of additional studies that reported pregnancy loss in twin pregnancies after amniocentesis but not identified by our original PUBMED search.

Study Selection

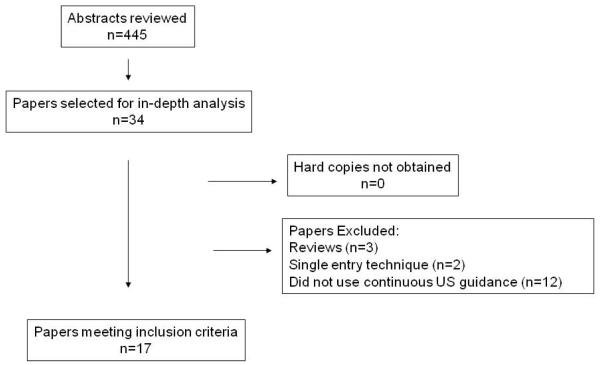

Studies that looked specifically at early amniocentesis (procedure performed less than 15 weeks gestation), third trimester amniocentesis, studies that were not published in English, studies which did not report the use of continuous ultrasound guidance during the amniocentesis, and studies which specifically studied only the single entry technique were excluded. Data were abstracted from the text, graphs and tables of each selected article. The selection process of the studies is presented in Figure 1. Both the first and second authors made the final decision about the inclusion and exclusion of studies and interpretation of data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus that was reached after discussion.

FIGURE 1.

Literature search flow charts

Data analysis

The definition of “loss” varied with each published study. For the purpose of this review, we used a composite definition of “loss” to include all cases with either miscarriage or stillbirth/intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD) of 1 or both fetuses at any gestational age. Data was extracted for the following categories: losses occurring at less than 24 weeks gestation, losses occurring at less than 28 weeks gestation, and total pregnancy losses to term (irrespective of gestational age).

Meta-Analyst was used for data analysis and for making the forest plots (Higgins et al, 2003, Wallace et al, 2009,). Forest plots summarize the results by providing point and interval estimates from each individual study, as well as a pooled estimate. Random effects (DerSimonian-Laird) models were used to pool the procedure-related loss estimates from the included studies (DerSimonian et al, 1986). The I2 statistic describes the proportion of variability between study estimates that is due to study heterogeneity. In testing for heterogeneity, our null hypothesis was that the parameter of interest studied (i.e. the proportion of losses or odds ratio) was the same between studies. We determined heterogeneity between studies by examining the I2 statistic, testing for heterogeneity, and looking for non-overlapping confidence intervals. Using these methods, we were able to determine if the procedure-related loss rate estimates from each of the studies differed too much thus making pooling questionable.

Lastly, of the articles which met inclusion criteria, the Methods and Results sections were evaluated to determine if monochorionic twins were included in the study population and, if so, whether reported loss rates were stratified by chorionicity.

Results

The results of our search strategy are shown in Figure 1. Four hundred and forty-five articles were found as a result of our search using the key words “amniocentesis”, “twins” and “twins”. Thirty-four abstracts were identified which reported loss rates after amniocentesis. All hard copies of the articles were obtained. (Insert Figure 1)

Of the 34 studies reviewed, 3 were review articles and 2 studied the single entry technique and were excluded. Twelve studies did not report routine use of continuous ultrasound guidance during their amniocenteses and were excluded leaving 17 studies for analysis. Of these 17 studies, 16 [94.1%] were retrospective in nature and one was prospective in design. Only 7 of the 17 [41.2%] studies included a control group (twin pregnancies that did not undergo genetic amniocentesis), and all 7 were retrospective.

The definition of “loss” varied across all 17 included studies (Table 1). Seven of the 17 studies defined loss as loss of “both fetuses” and one study defined loss as loss of “one or both fetuses”. The remaining 9 studies did not specify whether one or both fetuses were involved in cases of “loss”. Losses were also commonly classified by the gestational age at which they occurred or the interval between amniocentesis and when the “loss” occurred. The intervals most commonly reported in these 17 papers were ‘before 20 weeks’ (n= 3), ‘before 24 weeks’ (n=5) and ‘before 28 weeks’ (n=5). Other reported intervals included loss within 2 weeks of the procedure (n=2), within 4 weeks (n=1), within 6 weeks (n=1), and total pregnancy loss (n=2). (Insert Table 1)

Table 1.

Procedure related loss rates after amniocentesis in twin pregnancies

| # | Author | Years | Study Design | Amnio (n) | Control (n) | Study Definition of Loss | Amnio Loss Rate | Control Loss Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kappel et al | 1983-1987 | Retrospective | 48 | None | Expulsion of dead fetus before 28wks (including IUFD before 28wks) | 6/48 (12.5%) | NA |

| 2 | Pruggmayer et al | 1982-1989 | Retrospective | 98 | -- | Loss of both fetuses < 20wks Loss of both fetuses < 28wks |

8/98 (8.1%) | NA |

| 3 | Pruggmayer et al | 1985-1991 | Retrospective | 529 | -- | Loss to 20wks SAB < 28wks |

62/529 (11.7%) | NA |

| 4 | Wapner et al | 1984-1990 | Prospective | 70 | -- | Loss of both fetuses to 28wks | 3/70 (4.2%) | NA |

| 5 | Ghidini et al | 1987-1992 | Retrospective | 101 | 108 | Total loss rate= (SAB + stillbirths + neonatal deaths) / total # living fetuses initially present at 2nd trimester US |

4/101 (3.9%) | 4/108 (3.7%) |

| 6 | Reid et al | 1989-1995 | Retrospective | 50 | -- | Loss of a fetus for any reason within 6wks | 1/50 (0.02%) | NA |

| 7 | Kidd et al | 1980-1991 | Retrospective | 227 | 227 | SAB < 20wks of BOTH fetuses | 23/227 (10.1%) | 9/227 (3.9%) |

| 8 | Ko et al | 1986-1997 | Retrospective | 128 | 205 | SAB < 24wks Loss < 28wks |

8/128 (6.2%) | 9/205 (4.3%) |

| 9 | Yukobowich et al | 1990-1997 | Retrospective | 476 | 477 | Loss of BOTH within 4wks | 13/476 (2.73%) | 3/477 (0.6%) |

| 10 | Van Vugt et al | 1990-1993 | Retrospective | 8 | -- | No specific definition | 0/8 (0%) | NA |

| 11 | Toth-Pal et al | 1990-2001 | Retrospective | 155 | 292 | SAB < 24wks Preterm delivery between 24-28wks |

11/155 (5.8%) | 22/292 (7.5%) |

| 12 | Millaire et al | 1990-2004 | Retrospective | 132 | 248 | Loss of 1 or both fetuses at 15-24wks | 4/132 (3%) | 2/248 (0.8%) |

| 13 | Cahill et al | 1990-2006 | Retrospective | 311 | 1623 | Loss before 24wks (including miscarriage & IUFD) | 10/311 (3.2%) | 22/1623 (1.3%) |

| 14 | Daskalakis et al | 1993-2000 | Retrospective | 442 | -- | Loss of BOTH fetuses before 24wks | 18/442 (4%) | NA |

| 15 | Simonazzi et al | 2002-2007 | Retrospective | 100 | -- | Loss of BOTH fetuses < 24wks | 4/100 (4%) | NA |

| 16 | Hanprasertpong et al |

1998-2006 | Retrospective | 45 | -- | Loss < 14days | 3/45 (6.6%) | NA |

| 17 | Supadilokluck et al | 1992-2006 | Retrospective | 87 | -- | Loss within 2 weeks of BOTH fetuses | 4/87 (4.5%) | NA |

Spontaneous abortion (SAB)

The studies analyzed to generate a pooled amniocentesis-related loss rate at less than 24 weeks gestation were deemed acceptable in terms of homogeneity (I2=0%, p-value=0.4). The pooled amniocentesis-related loss rate at less than 24 weeks was therefore calculated and was found to be 3.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.6-4.7) (Figure 2). The 7 studies which reported total pregnancy loss rates in twins after amniocentesis vs control (no amniocentesis) were also found to be homogenous (I2=15% , p-value=0.3) and a pooled odds ratio for total pregnancy loss after amniocentesis was found to be 1.8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2-2.7) (Figure 3) indicating an increased risk of loss in the amniocentesis group vs control. The studies analyzed to generate a pooled amniocentesis-related loss rate less than 28 weeks (Figure 4) and an overall procedure-related loss rate to term (Figure 5) were deemed too heterogeneous (less than 28 weeks: I2=31% , p-value=0.08, loss rate to term: I2 43%, p-value<0.001) and therefore pooled loss rates for these categories were not accepted. (Insert Figure 2, 3, 4, 5)

FIGURE 2.

Post-amniocentesis pregnancy loss < 24 weeks. I2=0%, p-value 0.3. Proportion meta-analysis plot (random effects). Pooled loss-rate = 3.5% (97% CI 2.6-4.7).

FIGURE 3.

Total pregnancy loss in twins undergoing amniocentesis vs twins that did not undergo amniocentesis. Odds ratio = 1.8 (95% CI 1.2-2.7).

FIGURE 4.

Post-amniocentesis pregnancy loss < 28 weeks. Heterogeneity I2=31%. Proportion meta-analysis plot (random effects).

FIGURE 5.

Total post-amniocentesis pregnancy loss (to term). Heterogeneity I2=43%. Proportion meta-analysis plot (random effects).

Most studies did not report the chorionicity of twins in their cohorts, and only 2 studies reported specific loss rates for monochorionic pregnancies. Millaire et al (2006) reported no losses less than 24 weeks in 45 monochorionic twin pregnancies that had an amniocentesis. They did not, however, specify if of the 2 losses in the control group were monochorionic twin gestations. Cahill et al (2009) reported a significant difference in loss rates before 24 weeks in the monochorionic twins that had an amniocentesis compared to those that did not have an amniocentesis (7.7 vs 1.4% respectively, p-value=0.02).

Discussion

Our systemic review found a wide range in pregnancy loss rates reported after amniocentesis in twin pregnancies. After analysis, the procedure-related loss rates reported at less than 24 weeks were deemed similar enough for comparison and the calculated pooled loss rate was 3.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.6-4.7). When comparing the procedure-related loss to the background loss rate among controls, there appeared to be an increased risk of loss in the amniocentesis group with an odds ratio of 1.8. Although these findings may suggest a an increased risk of pregnancy loss after amniocentesis at these intervals, the available published data included in our analysis were too heterogeneous to allow for calculation of a pooled overall amniocentesis-related loss rate at 28 weeks and to term in twin gestations.

As our review shows, the definition of “pregnancy loss” widely varies according the mechanism of loss (fetal death or miscarriage/delivery) and the number of fetuses involved (one or both). Several studies defined “loss” as the “loss of both twins” (Anderson et al, 1990, Pruggmayer et al, 1992, Wapner et al, 1993, Sebire et al, 1996, Yukobowich et al, 2001, Daskalakis et al, 2009, Simonazzi et al, 2010), whereas one study (Millaire, 2006) specifically defined “loss” as “loss of 1 or both fetuses”. In addition, several studies specifically reported cases of stillbirth/ IUFD either as part of their “loss rate” or in addition to the overall “loss rate” (Elias et al, 1980, Goldstein et al, 1983, Palle et al, 1983, Librach et al, 1984, Tabsch et al, 1985, Pruggmayer et al, 1992, Ghidini et al, 1993, Kidd et al, 1997, Ko et al, 1998, Cahill et al, 2009). In our review, we sought to determine a pooled procedure-related loss rate that could be used to counsel patients considering amniocentesis in twin gestations, and accordingly we determined and recommend that the most clinically relevant definition of “loss” would include cases of delivery or IUFD of either one or both fetuses.

In addition to the variation with regard to the mechanism of loss and number of fetuses affected, published literature also includes varying definitions of the timing of “loss” after amniocentesis. In our review, the most common intervals used were loss at less than 24 and 28 weeks, but other studies also used loss before 20 weeks, loss within 2, 4, or 6 weeks of the amniocentesis, and overall pregnancy loss at any gestational age. Although it remains unclear which interval is the most appropriate by which to define a procedure-related loss, estimates of procedure-related loss rates must be evaluated in the context of the baseline risk of pregnancy loss among twin pregnancies. Yaron et al reported that twin pregnancies naturally carry a loss rate of about 6.3% up to 24 weeks and 8% of severe prematurity between 24- 28 weeks. (Yaron et al, 1999) Although the procedure-related loss rates varied between the studies included in our study, the pooled post-amniocentesis loss rates at < 24 weeks of 3.5% was comparable to this “natural loss rate”. Unfortunately, only seven of the studies identified had case-control study designs including a control group of twin pregnancies that did not have an amniocentesis (Kidd et al, 1997, Ko et al 1998, Yukobowich et al, 2001, Toth-Pal et al, 2004, Millaire et al, 2006, Ghidini et al, 2003, Cahill et al, 2009). Of these, four studies did not show a significant difference between loss rates in twin pregnancies that did and did not have an amniocentesis (Ghidini et al, 2003, Kidd et al 1997, Ko et al, 1998, Toth-Pal et al, 2004), whereas two demonstrated a significantly increased risk of loss among those who did undergo amniocentesis (Yukobowich et al, 2001, Cahill et al, 2009). Of note, the two studies which showed a significant difference had the largest sample size in each study group.

Chorionicity is another important factor to consider when assessing the procedure-related risk of pregnancy loss after amniocentesis in twin gestations. Given that both fetuses in monochorionic twin gestations arise from the same zygote, the karyotype of each fetus should in theory be identical. However, case reports exist showing monochorionic twins discordant for chromosomal abnormalities. (Rogers et al, 1985, Dallapiccola et al, 1985, Perlman et al, 1990) Although the precise incidence of heterokaryotypic monozygotic pregnancies remains unknown, it is likely a rare event. Although opinions vary, due to the small but reported risk of discordant karyotypes in monozygotic twins, some recommend sampling both sacs if the patient is undergoing an amniocentesis for prenatal genetic diagnosis in a monochorionic gestation. Our review identified only two studies which specifically reported loss rates after amniocentesis in monochorionic twin gestations. In the cohort reported by Cahill, only one sac was sampled in each of the eight monochorionic twin gestations who had amniocenteses (Cahill et al, 2009). Millaire et al sampled each sac in 25 out of the 45 monochorionic gestations (Millaire et al, 2006), but did not stratify loss rates between those monochorionic gestations in which one fetus was sampled and those in which both fetuses were sampled.

Another reason to address chorionicity when counseling patients regarding the risk of amniocentesis in twin gestations, is the increased risk of fetal and pregnancy loss among monochorionic twins and the potential impact of single fetal loss in these pregnancies. Monochorionic twins face an increased risk of perinatal morbidity due to unique complications of single placentation (twin to twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), twin reversed arterial perfusion (TRAP) sequence, unequal placental sharing) (Cleary-Goldman et al, 2005), but uncomplicated monochorionic twin gestations have also been shown to have an increased risk of spontaneous pregnancy loss compared to dichorionic twins (Lee et al, 2008). Furthermore, given that the loss of one monochorionic twin may have devastating neurodevelopmental consequences for the surviving co-twin, patients considering genetic amniocentesis in monochorionic twin pregnancies should be counseled regarding the impact of chorionicity on the implications of fetal loss.

In summary, patients considering amniocentesis in twin pregnancies should be informed that the risk of amniocentesis-related loss is likely increased above the baseline risk of loss among twin gestations, but that the exact loss rate is still unclear due to the heterogeneity of the published studies in terms of how the investigators defined “procedure-related loss” and the limited sample size of each of the published studies. Although we recommend defining “procedure-related loss” as “delivery or IUFD of either one or both fetuses” after amniocentesis, in order to obtain a consensus on what is the most appropriate definition of “procedure-related loss”, it would be useful to survey obstetricians across the country and determine the most commonly used definition of loss. Once a consensus is reached on the appropriate definition of loss, further studies utilizing a large prospective twin registry and a standard definition of “procedure-related loss” are necessary to determine true procedure-related loss rates after amniocentesis in twin gestations. In the interim, our pooled procedure-related loss rates and other loss rates reported in the literature should be interpreted in comparison to the spontaneous loss rate among twin gestations, and patients should be counseled regarding the baseline risk of pregnancy loss specific to either monochorionic or dichorionic gestations.

Acknowledgement

The project described was assisted by the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research which was supported by Grant Number UL1 RR024156 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at NCRR Website. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from NIH Roadmap website.

References

- ACOG Invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Dec;110:1459. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291570.63450.44. Practice Bulletin No. 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R, Goldberg J, Golbus M. Prenatal diagnosis in multiple gestation: 20 year’s experience with amniocentesis. Prenat Diag. 1990;10:25–28. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antsaklis A, Souka A, Daskalakis G, Kavalakis Y, et al. Second-trimester amniocentesis vs. chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis in multiple gestations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Nov;20(5):476–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel B, Kaminski M. Trends in the occurrence, determinants, and consequences of multiple births. Semin Perinatol. 2002;26:239. doi: 10.1053/sper.2002.34775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill A, Macones G, Stamilio D, Dicke J, et al. Pregnancy loss rate after mid-trimester amniocentesis in twin pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:257.e1–257.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary-Goldman J, D’Alton ME. Uncomplicated monochorionic diamniotic twins and the timing of delivery. PLoS Med. 2005 Jun;2(6):e180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020180. Epub Jun 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallapiccola B, Stomeo C, Ferranti B, Di Lecce A, et al. Discordant sex in one of three monozygotic triplets. J Med Genet. 1985;22:6–11. doi: 10.1136/jmg.22.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis G, Anastasakis E, Papantoniou N, Mesogitis S, et al. Second trimester amniocentesis in assisted conception versus spontaneously conceived twins. Fertility and Sterility. 2009 Jun;91(6):2572–2577. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias S, Gerbie A, Simpson L, Nadler L, et al. Genetic amniocentesis in twin gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Sep 15;138(2):169–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)90029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidini A, Lynch L, Hicks C, Alvarez M, et al. The risk of second-trimester amniocentesis in twin gestation: A case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1013–1016. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90045-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AI, Stills SM. Midtrimester amniocentesis in twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Nov;62(5):659–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanprasertpong T, Kor-anantakul O, Prasartwanakit V, Leetanaporn R, et al. Outcome of second trimester amniocentesis in twin pregnancies at Songklanagarind Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008 Nov;91(11):1639–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003 Sep 6;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappel B, Nielsen J, Hansen K Brogaard, Mikkelsen M, et al. Spontaneous abortion following mid-trimester amniocentesis. Clinical significance of placental perforation and blood-stained amniotic fluid. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987 Jan;94(1):50–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S, Lancaster P, Anderson J, Boogert A, et al. A cohort study of pregnancy outcome after amniocentesis in twin pregnancy. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 1997;11:200–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1997.d01-13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko T, Tseng L, Hwa H. Second-trimester genetic amniocentesis in twin pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1998;61:285–287. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YM, Wylie BJ, Simpson LL, D’Alton ME. Twin chorionicity and the risk of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Feb;111(2 Pt 1):301–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318160d65d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librach L, Doran T, Benzie R, Jones J. Genetic amniocentesis in seventy twin pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984 Mar 1;148(5):585–91. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90753-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births final data 2002. No 10. Vol 42. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Kung H, Mathews T, Hoyert D, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2006. Pediatrics. 2008;121:788. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millaire M, Bujold E, Morency AM, Gauthier R. Mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis in twin pregnancy and the risk of fetal loss. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28:512–8. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palle C, Andersen J, Tabor A, Lauritsen J, et al. Increased risk of abortion after genetic amniocentesis in twin pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 1983 Apr-Jun;3(2):83–9. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970030202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman E, Stetten G, Tuck-Muller C, Farber RA, et al. Sexual discordance in monozygotic twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;37:551–557. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruggmayer M, Bartels I, Rauskolb R, Osmers R. Risk of abortion following genetic amniocentesis in the 2d trimester in twin pregnancies. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1990 Oct;50(10):810–2. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruggmayer M, Joahoda M, Van der Pol J, Baumann P, et al. Genetic amniocentesis in twin pregnancies: Results of a multicenter study of 529 cases. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2:6–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1992.02010006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid K, Gurrin L, Dickinson J, Newnham J, et al. Pregnancy loss rates following second trimester genetic amniocentesis. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;39(3):281–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1999.tb03397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JG, Voullaire L, Gold H. Monozygotic twins discordant for trisomy 21. Am J Med Genet. 1982;11:143–146. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebire N, Noble P, Odibo A, Malligiannis P, et al. Single uterine artery entry for genetic amniocentesis in twin pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:26–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1996.07010026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonazzi G, Curti A, Farina A, Pilu G, et al. Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling in twin gestations: which is the best sampling technique? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jan 6; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.016. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling L, Kiil C, Larsen LU, Qvist I, et al. Naturally conceived twins with monochorionic placentation have the highest risk of fetal loss. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Oct;28(5):644–52. doi: 10.1002/uog.3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supadilokluck S, Tongprasert F, Tongsong T, Wanapirak C, et al. Amniocentesis in twin pregnancies. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009 Aug;280(2):207–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0894-y. Epub 2008 Dec 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabsh KM, Crandall B, Lebherz TB, Howard J. Genetic amniocentesis in twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:843–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth-Pal E, Papp C, Beke A, Zoltan B, et al. Genetic amniocentesis in multiple pregnancy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2004;19:138–144. doi: 10.1159/000075138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vugt J, Nieuwint A, van Geijin HP. Single needle insertion: an alternative technique for early second trimester genetic twin amniocentesis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1995;10:178–81. doi: 10.1159/000264229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BC, Schmid C, Lau J, Trikalinos T. Meta-analyst: software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009;9(1):80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wapner R, Johnson A, Davis G. Prenatal diagnosis in twin gestations: A comparison between second trimester amniocentesis and first trimester chorionic villus sampling. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaron Y, Bryant-Greenwood PK, Dave N, Moldenhauer J, et al. Multifetal pregnancy reductions of triplets to twins: comparison with nonreduced triplets and twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999 May;180(5):1268–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukobowich E, Anteby E, Cohen S, Lavy Y, et al. Risk of fetal loss in twin pregnancies undergoing second trimester amniocentesis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(2):213–234. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]