Abstract

Background

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends the use of survivorship care plans (SCPs) for all cancer survivors. Developing useful SCPs requires understanding what survivors and their providers need and how SCPs can be implemented in practice.

Methods

We reviewed published studies investigating the perspectives of stakeholders (survivors, primary care providers, and oncology providers) regarding the content and use of SCPs. We surveyed all NCI-designated cancer centers about the extent to which SCPs for breast and colorectal cancer survivors are in use, their concordance with the IOM's recommendation, and details about SCP delivery.

Results

Survivors and primary care providers typically lack the information the IOM suggested should be included in SCPs. Oncology providers view SCPs favorably but express concerns about feasibility of their implementation. Fewer than half (43%) of NCI-designated cancer centers deliver SCPs to their breast or colorectal cancer survivors. Of those that do, none deliver SCPs that include all components recommended by the IOM.

Conclusion

Survivors’ and providers’ opinions about the use of SCPs are favorable, but there are barriers to implementation. SCPs are not widely used in NCI-designated cancer centers. Variation in practice is substantial, and many components recommended by the IOM framework are rarely included.

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute recently estimated that as of 2007, there were 11.7 million cancer survivors, and this number is expected to grow with continued advances in cancer therapy and the aging of the population.1, 2 The 2005 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, highlighted patients’ special needs that arise from persistent toxicities and late-occurring health problems from the cancer and its treatment.3-8 Financial, legal, and other logistical challenges exist as well.3, 9, 10 Even survivors’ receipt of general preventive health care can fall behind that of individuals without a cancer diagnosis.11

To ease the challenges of cancer survivorship, the IOM recommends the use of survivorship care plans (SCPs). SCPs are personalized documents, provided at the end of treatment by the coordinating oncology clinician, that summarize the patient's diagnosis and treatment, describe possible late effects and other challenges commonly faced by survivors, recommend ongoing care (both self maintenance and care received by healthcare providers), and present resources for addressing practical and other issues in survivorship care. Survivors can use the SCP to learn about health-promoting behaviors, seek appropriate medical and psychological care, and learn about other relevant resources. The survivors can also share their SCP with their primary care provider to promote coordinated ongoing care.

The use of SCPs was proposed by the IOM in 2005. Six years later, important questions remain about SCPs. Do SCPs address known deficiencies in the care of cancer survivors? Do they promote comprehensive care? Can they be developed in busy clinics? Are they being used once provided? When is the optimal time to provide them? Have SCPs been implemented widely? Do SCPs include all the information recommended by the IOM? This review evaluates the evidence to date regarding outcomes of use of SCPs, informational needs and preferences of survivors and providers, feasibility of implementation, and satisfaction with SCPs. To answer questions about how SCPs are being used in practice, we conclude with a presentation of the results of a survey regarding the use and content of SCPs at NCI-designated cancer centers.

Assessment of survivorship care plans

Researchers, clinicians, and other experts in cancer survivorship have endorsed the use of SCPs.12-21 Experts may disagree or be undecided about specifics of SCP content, format, and delivery, but the general consensus is one of strong support even in the absence of firm evidence. Indeed, in its report proposing the use of SCPs, the authors of the IOM argue that because of the vast potential benefits of SCPs and the minimal harm, development and dissemination of SCPs should proceed before waiting for a solid evidence base to be established.3 Accordingly, practitioners have moved forward with SCPs. Many organizations, including the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the Lance Armstrong Foundation, have developed publicly available SCP templates.22, 23 The American Cancer Society web site links to these and other publicly available survivorship care plans at http://www.cancer.org/Treatment/SurvivorshipDuringandAfterTreatment/SurvivorshipCar ePlans/index.24 Further, SCPs have been endorsed by professional cancer societies, including ASCO,25, 26 and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer has included the provision of SCPs as part of their cancer program standards for 2012.27

Stepping back to evaluate the effectiveness of SCPs is difficult, because many of the goals of SCP implementation are not immediate, such as improving adherence to screening and surveillance guidelines, fostering coordinated care between all providers, promoting multidisciplinary comprehensive care, and ultimately improving survivors’ physical and psychological health. SCPs are commonly evaluated in terms of how well they address survivors’ and providers’ needs and preferences for information. These stakeholders provide important viewpoints on their satisfaction with coordination of care, clinician-patient communication, and the content and use of SCPs. 14, 28 An overview of the studies of relevant stakeholder perspectives is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies of stakeholder perspectives on SCP-related endpoints

| First author (year) | Design and sample (N) | Cancers addressed | Location of study | SCP-related study endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivor perspectives | ||||

| Arora46 ( 2011) | Mailed population-based survey (N=623) | Leukemia, bladder, colorectal | California, US | Perceptions of quality of follow-up care, including information exchange with doctors |

| Baravelli44 (2009) | Mailed questionnaire (N=20) and structured telephone interview with clinical sample at a cancer center (N=12) | Colorectal | Melbourne, Australia | Preferences for the content of SCPS and opinions about an SCP for a fictitious patient |

| Burke Beckjord29 (2008) | Mailed population-based survey (N=1,040) | Bladder, colorectal, adult-onset leukemia, non-Hodgkins lymphoma | California, US | Information needs and perceived quality of care |

| Blinder48 (under review) | Telephone survey of patients in multiple community practices (N=174) | Breast | US | Reactions to SCPs in a pilot study |

| Brennan31 (2011) | Semi-structured telephone interviews with members of a national support and advocacy group (N=20) | Breast | Australia | Opinions about SCP content and survivorship care |

| Burg32 (2009) | Focus groups of minority support group members (N=32) | Breast | Southeast urban area, US | Opinions about post-treatment care and attitudes toward an SCP template |

| Hawkins34 (2008) | Longitudinal self-administered survey in community oncology practices nationwide (N=731) | Breast, lung, genitourinary, hematologic, gastrointestinal, head and neck, gynecologic | US | Information needs and perceived adequacy of information |

| Hewitt38 (2007) | Focus groups (N=30-36) | Various types | Virginia, US | Opinions about post-treatment care and an SCP template |

| Hodgkinson30 (2006) | Mailed questionnaire of patients seen in 2 hospital outpatient clinics (N=353) | Breast, gynecologic, prostate, colorectal, and other | Australia | Unmet informational and other needs |

| Jefford59 (2011) | Questionnaires (N=10) and interviews (N=8) of patients at cancer center | Colorectal | Australia | Reactions to a pilot test of a post-treatment supportive care program, which included an SCP |

| Kantsiper39 (2009) | Focus groups of patients in a community (N=21) | Breast | Maryland, US | Opinions regarding follow-up care, unmet needs, and use of SCPs. |

| Mao47 (2009) | Questionnaire of patients at large university hospital (N=286) | Breast | Pennsylvania, US | Perspectives on primary care follow-up |

| Marbach33 (2011) | Focus groups of patients from clinic in an academic medical center (N=40) | Prostate, genitourinary, skin, breast, gynecologic, gastrointestinal, sarcoma, head and neck, brain, pancreatic, lung | Midwest, US | Reponses to SCP template and opinions about SCP content and delivery |

| Miller39 (2007) | Qualitative interviews of patients from a cancer center's pilot survivorship program (N=5) | Breast | Michigan, US | Reactions to receipt of SCP |

| Roundtree43 (2010) | Focus groups of patients in a cancer center (N=33) | Breast | Texas, US | Attitudes regarding unmet medical and information needs |

| Royak-Schaler40 (2008) | Focus groups and questionnaires of African American members of support groups (N=39) | Breast | Maryland, US | Opinions on patient-physician communication regarding survivorship care and format and delivery of survivorship information |

| Smith41 (2011) | Focus groups of patients in a regional health system (N=26) | Breast | British Columbia, Canada | Preferences for content and format of SCPs |

| Primary care provider perspectives | ||||

| Baravelli44 (2009) | Structured telephone interview of primary care providers of patients in a clinic at a cancer center (N=14) | Colorectal | Melbourne, Australia | Opinions about an SCP for a fictitious patient |

| Bober52 (2009) | Mailed survey to internal medicine faculty at academic center and community-based practices (N=227) | NA | Colorado, US | Opinions about providing survivorship care and receiving information about cancer survivorship |

| Del Giudice53 (2009) | National mailed survey (N=330) | Prostate, colorectal, breast, lymphoma | Canada | Attitudes toward routine follow-up care of survivors and the role of primary care providers |

| Hewitt38 (2007) | Focus groups of primary care physicians identified in professional groups (N=14) | Various | Maryland and Missouri, US | Reactions to post-treatment follow-up care and specifics of care-planning |

| Kantsiper42 (2009) | Focus groups of primary care providers in a community network (N=15) | Breast | Maryland, US | Reflections on transition to follow-up, communication, patient needs, and provider roles |

| Miller39 (2007) | Telephone interviews of primary care providers who treat patients in a cancer center's survivorship program (N=5) | Breast | Michigan, US | Reactions to the SCPs of their patients |

| Nissen54 (2007) | Mailed questionnaire to patients in health system (N=132) | Breast, colorectal | Minnesota, US | Opinions about role in follow-up care |

| Watson56 (2010 | Online questionnaire survey of primary care providers visiting a medical web site(N=200) | NA | UK | Views on survivorship care and the use of SCPs |

| Oncology provider perspectives | ||||

| Hewitt38 (2007) | Structured interviews of oncologists from national database (N=20) and focus groups of oncology nurses at oncology nursing conference(N=34) | NA | Maryland and Missouri, US (oncologists) and US (nurses) | Opinions about post-treatment care and the use of SCPs |

| Kantsiper42 (2009) | Focus groups of oncologists at an academic medical center (N=16) | Breast | Maryland, US | Reflections on transition to followup, communication, patient needs, and provider roles |

| Watson56 (2010) | Online questionnaire survey of oncologists visiting a medical web site (N=100) | NA | UK | Views on follow-up care and SCP use |

A smaller number of studies have evaluated the impact of SCPs on processes of care and health outcomes. The following sections review the literature regarding SCPs, including studies of stakeholder perspectives and of the impact of SCPs.

Stakeholder perspectives: The cancer survivor

A primary goal of SCP implementation is to inform cancer survivors about what they have experienced, what to expect in the future, and how to pursue and manage their ongoing care. Survivors report unmet informational needs across many topics that are relevant to this goal. 29, 30 To understand how SCPs can address unmet needs, this section summarizes the evidence about survivors’ needs and preferences for information.

Information about diagnosis and treatment

The IOM report recommends that a SCP should summarize the survivor's diagnosis and treatment. Survivors in multiple studies reported being unsure of their diagnosis and treatment,31-34 particularly the less salient details, such as presence of metastasis and which diagnostic tests were used .35, 36 This is especially true for information that was presented right after diagnosis, a time when survivors have described feeling confused and overwhelmed.37-39 However, cancer survivors have reported receiving too much information when they could not focus on it properly.38, 40 During treatment, patients may be confused by medical terminology and jargon.32, 33, 39 Reflecting this informational need, participants in one breast cancer survivor focus group felt that the inclusion of information about diagnosis and treatment in a SCP is important.41

Information about persistent toxicities and late effects

Survivors are often unprepared for the persistence of long-term toxicities and the subsequent development of late effects,31, 32, 40, 42, 43 and many would like more information about them.29, 33, 41 Breast cancer survivors want to know what to expect in terms of physical symptoms (such as fatigue, weight gain, and hot flashes).31, 42 Some breast cancer survivors reported that while they were somewhat prepared for some late effects (such as lymphedema and hot flashes), they were unprepared for other late effects, such as skin pigment changes and sexual side effects.32 Colorectal cancer survivors also mentioned fatigue as a symptom they had not been prepared to face.37 Breast cancer survivors in two focus group studies reported a need for information on symptoms and signs that might indicate a cancer recurrence.32, 33

While awareness of potential physical problems was deemed important, survivors more highly valued being alerted to and informed about potential psychological issues.29, 32, 38, 44 Survivors have reported that they lack information about the possibility of depression and other emotional difficulties.31, 38, 42 When presented with sample SCPs, survivors particularly appreciate attention to possible psychological consequences of cancer.33, 37, 38

Information about ongoing prevention and health promotion

Survivors report needing more information about ongoing prevention of recurrences, second cancers, and other cancer-related health problems. Strategies for follow-up testing (i.e., screening for new cancers or surveillance for recurrence or other late effects) are often reported to be unclear.31-33, 39, 40 In a survey of information needs, the topic that the most survivors (71%) felt they needed more information about was tests and treatments, followed by information about health promotion strategies (68%).29 Looking forward from treatment, survivors were unsure what they should do next to stay healthy.31-33, 40 Survivors report that providing information about ongoing care in a SCP would foster self-management by helping survivors monitor for late effects, adopt healthy behaviors, and get appropriate surveillance.32-34, 39, 42, 45, 46

Information about practical resources

Only two studies investigated survivors’ preferences for information about financial, legal, or insurance issues, which the IOM recommends including in SCPs. A study of breast cancer survivors and a study of colorectal cancer survivors both found that patients think SCPs should contain information about financial and legal issues.32, 37

Information about coordination of care

Coordination of oncology and primary care remains a concern for survivors,31, 39, 43, 46,47 and they value SCPs for their role in improving communication between providers.31-33, 39, 42, 48 Breast cancer survivors have reported wanting to know what information their primary care was given, and a SCP that is shared via the survivor would address this issue.39, 41 Survivors in one study reported that they receive conflicting medical advice that could be reconciled with a unitary SCP.31 A focus group study of survivors of multiple cancers echoed these findings – survivors felt their providers were not always in agreement about the plan of care, and a written plan would clarify ongoing care.33

Preferred length and level of detail of the SCP

Some existing SCPs are relatively concise summaries of treatment and recommendations for ongoing care, while other SCPs have a broader scope oriented toward providing comprehensive information in narrative format. Survivors have varied preferences for the amount of detail included in a SCP,41 although surveys of those who have used or viewed different plans suggest that survivors prefer more detail rather than less. In response to the breast cancer ASCO treatment summary and care plan, survivors felt the language was too technical and preferred more detail about managing their own care.32, 38 Among users of the LIVESTRONG Care Plan, a more narrative SCP, 52% felt there was just enough information, but 31% felt that they could use more information.49

Preferred format of the SCP

Although designed to be printed and delivered by the oncology provider, the information in SCPs may be delivered and stored on the internet, creating a resource that could be accessed in various locations as needed. This is especially useful as a portable record, as survivors move between providers.14 Breast cancer survivors in one study were receptive to an internet-based format,38 although another study found that survivors preferred a paper document over an electronic document.33 While the internet is a primary source of information for many adults, cancer survivors access the internet less than those not personally affected by cancer.50 Among survivors, there is a digital divide; survivors who are members of minority groups, have less education, live in rural areas, have poorer physical health, or poorer mental health are less likely to have access to the internet.50 Creating a document that survivors can only develop or access on the internet may alienate groups that traditionally have needed the most support; it is important to ensure that internet-based SCPs can be printed and delivered to survivors as needed.

Preferred timing of delivery of the SCP

Although the IOM recommends delivering a SCP at the end of treatment, survivors’ opinions about the timing of SCP delivery vary, with some preferring to receive the SCP at the last visit and others well afterwards.33, 41 The ASCO treatment plan and summary was designed to be an ongoing record of patient care, to be filled in at the start of treatment and updated thereafter.51 One proposal is to maintain an ongoing update of a SCP, so that it can be referred to throughout treatment in discussions with patients.14, 18 Clinical practice constraints may limit the extent to which oncologists are able to keep a dynamic SCP updated throughout treatment. An alternative is to present a single static treatment plan at the start of treatment. In a pilot project in which the breast cancer ASCO treatment plan was delivered at the start of treatment (in addition to a summary provided at the end of treatment), survivors reported that it was comforting to have their planned course of treatment described clearly so that they could share it with their family and use it to discuss plans with their doctors.48

Overall preferences for SCPs

The reactions of survivors to descriptions of SCPs, hypothetical SCPs, and personalized SCPs have been overwhelmingly positive.33, 38,32, 44, 48 In a pilot test of a SCP for breast cancer, 75% of participants who remembered receiving a SCP said it gave them peace of mind, and 91% found it useful.48 Similarly, in an interview study of colorectal cancer survivors in which survivors viewed a sample SCP, all participants endorsed SCPs as useful, reassuring, empowering, and helpful.44 Beyond meeting the informational needs described above, survivors appreciate a written record with recommendations for ongoing care and report that, in contrast, they often find oral presentation of information to be overwhelming.31-33, 38, 44 Another reported benefit of SCPs is the ability to share the document with family.31, 33, 38

Stakeholder perspectives: The primary care provider

SCPs are targeted not only to survivors, but also to primary care providers. This section reviews the evidence on primary care providers’ information needs, their opinions about coordination of care, and their perspectives on how SCPs would affect their care of cancer survivors.

Diagnosis and treatment summary

There is little evidence regarding whether primary care providers feel that their knowledge of their patients’ cancer diagnosis and treatment is sufficient to provide optimal care. A survey of primary care providers found that 36% report having inadequate access to their patients’ treatment history.52 Primary care providers generally favor the receipt of a summary of treatment and diagnosis,38, 39, 44, 52 and they agree that a concise treatment summary is both relevant and critical to ongoing care.39, 44 One study found that providers especially valued information about treatment complications that the patient experienced.52

Post-treatment cancer follow-up

Primary care providers may not feel they have adequate skills or training to provide cancer follow-up care. A survey of primary care providers found that the number of providers who were comfortable with accepting exclusive responsibility for follow-up cancer care two years after treatment completion was fairly low (50-55% for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers and 42% for lymphomas).53 Primary care providers in another survey study had similarly low confidence in assuming responsibility for breast and colorectal cancer survivors.54 About half were comfortable being in charge of surveillance for breast and colorectal cancer recurrence (49 and 55%, respectively), and fewer were confident that they were following guidelines for breast and colorectal cancer survivorship (41% and 45%, respectively).55

One of the most important reasons that PCPs feel unprepared to provide cancer follow-up to survivors is that they are unfamiliar with cancer survivorship guidelines and recommendations. A study of primary care providers found that more than 90% were unaware of the IOM report on the needs of cancer survivors.52 Another survey study found that 84% percent of respondents were unsure about the type, frequency, or duration of surveillance tests for breast and colorectal cancer.54 Receiving printed guidelines was endorsed by over 90% of providers in two studies as a method of facilitating care for cancer survivors,52, 53 suggesting that SCPs that include guidelines for care would be welcomed by primary care providers.

Detecting and managing late effects

Primary care providers may lack information about the late effects of cancer and its treatment. Half of primary care providers in a survey study were not comfortable evaluating late effects, and 48% felt unprepared to manage late effects.52 Further, there are disparate views of who is responsible for managing late effects of treatment.42, 52 Primary care providers vary in their understanding of late effects of cancer, but they generally report that receiving information about late effects would be useful.44, 52 One study found that providers favored the receipt of patient-specific recommendations for managing late effects of treatment.52

Health promotion and psychosocial support

Preferences among primary care providers seem less strong for receiving information about recommended healthy behaviors, such as diet and exercise, most likely because they are experts in managing multiple health conditions, including recommending and supporting behavior changes for their patients. Therefore, receiving information about changes in lifestyle may not be necessary to primary care providers unless there are oncology-specific recommendations. Primary care providers are divided about the value of including information about healthy behaviors in a SCP, with some finding the information useful and others feeling comfortable without it.37, 44 Similarly, information about addressing psychosocial issues was valued by some providers, while others felt they would address psychosocial issues regardless of a cancer diagnosis.44 One survey found that 46% of primary care providers reported limited access to mental health referrals for survivors, although how access was limited was not specified.52

Opinions about coordination of care

Similar to the views of survivors, primary care providers note dissatisfaction with communication with the oncology provider.55, 56 In a survey study of primary care providers, there was substantial uncertainty about who was providing preventive health care, concern about duplication of care, and concern about missed care.54 Some primary care providers reported that knowing which providers are responsible for each element of follow-up was a significant problem, and a summary of the surveillance plan would help coordination to avoid both gaps in care and duplication of services.39, 44, 55 SCPs are seen by primary care providers as fostering a collaborative approach to patient care.39, 52

Delivery of SCPs

Another issue is how primary care providers wish to receive SCPs. SCPs are intended to be delivered to cancer survivors, who then may choose to share the document with their primary care provider. Cancer survivors who change primary care providers are necessarily in the role of delivering the SCP to their new providers. However, primary care providers in a survey study preferred survivor-specific information to come directly from the specialist than via the patient (92% vs. 67%), and they would trust the information more if it came directly from the oncology provider.53

Overall preferences for SCPs

In summary, primary care providers report a lack of comfort treating cancer survivors, although they may feel more comfortable if they have a SCP. On the whole, when asked about SCPs or written reports from oncology providers, primary care providers favored the use of SCPs,38, 39 and providers in one study felt SCPs should be incorporated as the standard of care.39 In a survey study, 95% of providers felt a patient-specific letter from the oncology provider would help them provide exclusive care.53 Primary care physicians in a focus group study felt that a single document would be preferable to having to read multiple letters from the oncology provider.38

Stakeholder perspectives: The oncology provider

The third group of stakeholders in the development and use of SCPs is oncology providers. Unless the SCP is created by the survivor (for example, by using an online template), oncologists and oncology nurses are responsible for choosing or creating the SCP template, collecting information, completing the tailored document, and disseminating it to the patient, often within the context of a dedicated clinical visit. The buy-in of oncology providers is critical for SCPs to be used, and this section reviews the evidence regarding the preferences of oncology clinicians and the challenges they face in providing SCPs.

Support for SCP use

Oncology providers reported that providing a SCP could be useful to survivors. 38,56 They note that it could reduce anxiety about what will happen to survivors after treatment completion and could improve communication, either between oncology providers if the patient changed to a different provider or health care plan or between the oncology provider and the primary care provider.38, 42

Challenges of implementation

Oncology providers have pragmatic concerns about the implementation of SCPs. In a review of the practices of a sample of cancer centers that have survivorship programs, key informants at each site reported that although they were committed to using SCPs, there were critical barriers. Choosing a format and finding the time, personnel, and resources to complete each individual plan were challenging.57 Automated completion of SCPs by pulling relevant information from an electronic medical record may ease the burden on oncology providers.18, 58

Oncology nurses have reported feeling capable of completing and delivering SCPs to patients.38 However, they also report that completing SCPs would take more time than they have available to them, especially for those without access to an electronic medical record.38 Nurses agreed that implementing SCPs would require resource allocation, a method of adequate reimbursement, and the support of attending physicians.38

In-depth oncologist interviews revealed that they were not uniformly interested in providing SCPs, because they require extra documentation that would not replace letters to other physicians treating the patient. Reimbursement for completing a SCP was an issue for oncologists, but the time involved appeared to be the greatest barrier – oncologists typically agreed that a SCP should take no longer than 20 minutes to complete.38 Time constraints have been cited in other studies as a barrier to implementation.39, 56 Indeed, a pilot study found that a research assistant could complete a SCP for colorectal cancer survivor in an average of 1 to 1.5 hours, and further time was required for a nurse to check the SCP.59 Two studies found that the end-of-treatment appointment to review of the SCP took an average of an hour.39, 59

Survivorship care plans: processes of care and health outcomes

Few studies have evaluated the effect of SCPs on clinical care. Two studies have measured the effect of SCP delivery on processes of care. In the context of adult survivors of childhood cancers, Oeffinger et al. created a treatment summary and care plan for high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma survivors participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.60 The short SCP focused on breast cancer and cardiovascular risks, as appropriate to each participant's gender and risk profile, and was mailed to survivors. Post-test rates of mammogram and echocardiogram receipt suggested that the SCP increased the use of these early-detection measures in adult survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma.

Similarly, in a trial addressing survivors of early stage breast cancer, Grunfeld and colleagues randomized survivors to follow-up with either usual care (follow-up with the treating oncologist) or care from a family physician.61 A short SCP summarizing treatment and recommending surveillance was provided to the family physician. Neither the rate of recurrence-related serious adverse effects nor health-related quality of life differed between the two groups. The effect of the SCP was not separately tested in this study, but results suggest that family physicians who are informed about ongoing care (via a SCP) are equipped to care for survivors of early stage breast cancer.

A recent trial by Grunfeld et al. is the only study to investigate the role of SCPs on health outcomes.62 (in press) In a randomized controlled trial of survivors of 408 early stage breast cancer, all patients had their care transferred to a primary care provider for exclusive follow-up. Patients in the intervention group additionally received a comprehensive SCP that was reviewed in a 30-minute educational session with an oncology nurse. The SCP was also sent to the patient's primary care provider. A year after the intervention was delivered, there were no differences detected between groups on self-reported health outcomes, including cancer-specific distress, generalized distress, patient satisfaction, and general health status. Self-reported continuity of care and identification of the primary care provider as the physician primarily responsible for follow-up also did not vary between groups. These findings suggest that for early stage breast cancer survivors, a SCP in itself may not improve health outcomes. However, actual care provided by primary care providers was not assessed; the possibility remains that health outcomes may differ if primary care providers who receive SCPs deliver care differently than providers who do not receive SCPs.

Summary of research on survivorship care plans

Studies of cancer survivors uniformly show a lack of, and desire for, cancer survivorship information. Cancer survivors appear to have needs that may be met with the information provided in SCPs, and they generally approve of SCPs. Similarly, primary care providers report discomfort providing follow-up care to cancer survivors and generally approve of SCPs for their concise medical records and consolidated recording of guidelines and other recommended care. Oncology providers, at least in theory, favor the use of SCPs too.

The barriers to SCP implementation are likely not related to a lack of buy-in from survivors, primary care providers, or oncology providers. Instead, the challenges of integrating SCPs (which require time, personnel, and other resources) into clinical practice may outweigh the benefits perceived by oncology providers.

As Table 1 shows, the evidence base is currently skewed toward focus groups and qualitative interview studies, which yield rich qualitative data from a small number of survivors.31-33, 38-41, 43, 44, 59 Qualitative studies are essential for generating a broad knowledge base about patient needs and preferences and for describing the coordination of care.58, 63 However, their external validity is limited, and such studies should be considered valuable first steps in understanding stakeholders’ perspectives. As these qualitative studies give us a clearer picture of stakeholder perspectives, research should move toward larger observational studies and trials.63

The recent trial by Grunfeld et al. is an example of this needed research.62 The finding that self-reported health outcomes are not affected by the use of SCPs in early breast cancer survivors leads to important questions about what health outcomes SCPs may be likely to address, how to measure important outcomes, and which populations may benefit most from SCPs.

Ayanian and Jacobsen described patient satisfaction as an important outcome of SCP use – specifically satisfaction with follow-up care, coordination of care, and communication with other providers.28 Earle proposed categories of important outcomes to evaluate SCPs, ranging from short-term outcomes like acceptability to long-term outcomes, such as survival.58 Other outcomes could include survivors’ awareness of their cancer history, their patterns of visits to different provider types, receipt of recommended testing, and whether survivors’ lingering and late effects are being appropriately managed. A randomized controlled trial of colorectal SCPs is currently underway looking at patient knowledge, patient satisfaction with care, and self-efficacy in obtaining follow-up care.63 Given the logistical barriers to SCP use, Earle proposed that an important line of research would focus on estimating the resources needed to create and implement SCPs and whether these costs would be offset by benefits of SCPs.14

Most studies of SCPs are limited to survivors of breast cancer and their providers.31, 32, 39-43, 47, 48 Studies of SCPs need to expand to assess the desirability and practicality of a SCP for survivors of different cancers. Larger studies are better able to capture the sources of variation in needs and preferences, such as the demographic and clinical characteristics of cancer survivors.

For those who are creating SCPs, there are still many unanswered questions about the optimal format and delivery. It is important to pool the available evidence from survivors and providers to develop SCPs that maximize their support and use while minimizing barriers. Although themes emerge within each group of stakeholders, variations in individuals’ needs and preferences necessarily occur, and developers of SCPs need to make decisions and compromises on various aspects of the content and delivery of SCPs. Examples include refining the content to a good balance of brevity and comprehensiveness and integrating the delivery of SCPs into clinical practice without overburdening clinicians.

National dissemination of SCPs: a review of existing SCPs

Despite the evidence that survivors and primary care providers are eager for the information in SCPs, the burden on oncology practices may stall the implementation of this intervention. It is still unknown whether the use of SCPs in clinical practice is widespread. We conducted an original search to understand the use of SCPs and the extent to which existing SCPs contain the elements of information recommended by the IOM. We hypothesized that the uptake of this intervention would be low, and the content itself would typically not be as comprehensive as the IOM framework. We aimed to describe the use of SCPs among National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated Cancer Centers and Comprehensive Cancer Centers. While these institutions do not represent all oncology practices, they may have the resources to be at the forefront of innovation for survivorship care. As a starting point, we focused on SCPs for survivors of colorectal and breast cancer – two large populations for whom SCP templates have been made available by a number of organizations.

Methods of SCP collection and review

Collection of SCPs

We requested SCPs for breast and colorectal cancer survivors from the 53 NCI–designated Cancer Centers and Comprehensive Cancer Centers that treated adults with cancer as of July 2009. After identifying each center's medical director, director of survivorship services, or director of breast and colorectal cancer clinics (in that order), we contacted them by email. We asked that our request be forwarded to relevant personnel if necessary. We inquired 1) whether SCPs were in use for patients with breast or colorectal cancer, and 2) if so, whether we could obtain a copy of the SCP(s) the center has in use. Inquiries began in August 2009 and were followed up with further emails and phone calls as needed. All NCI-designated centers responded by June 2010. Contacts were assured confidentiality. We promised that information about SCPs shared with us would not be linked to specific institutions, and any SCPs we received would not be made publicly available. We received either blank templates of SCPs, de-identified or hypothetical completed SCPs, or both, as offered by the institution. This study was deemed exempt from human subjects review at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Review of SCPs

In order to distinguish SCPs from other educational materials (such as brochures about post-treatment care), we decided a priori to include only SCPs that 1) are completed individually for each survivor, 2) provide a summary of treatment or medical recommendations for that survivor and 3) are provided after cancer treatment is complete. Based on our interpretation of the wording in the IOM report, we operationalized the 18 sections of the IOM framework of recommended SCP content into 35 evaluable components. We then pre-specified criteria for determining whether each component was present (Table 2). Some numbered sections of the IOM framework were subdivided into multiple components to enable a more granular evaluation. These criteria specified the minimum standards for categorizing each component as present or absent.

Table 2.

Operationalization of IOM framework for survivorship care plans

| IOM framework | Components of the framework and criteria for the evaluation of breast and colorectal survivorship care plans: when component was scored as present |

|---|---|

| Treatment summary | |

| 1. Diagnostic tests performed and results. | 1. Not included in review because all diagnostic tests for breast and colorectal cancer are biopsies, and results of biopsies will fall under Tumor characteristics (below) |

| 2. Tumor characteristics (e.g., site(s), stage and grade, hormone receptor status, marker information). | 2. Any of the following: site, stage, and grade for breast and colorectal cancers; hormone receptor status only for breast cancer |

| 3. Dates of treatment initiation and completion. | 3. Assessed individually for each treatment type, as described in #4 below |

| 4. Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, transplant, hormonal therapy, or gene or other therapies provided, including agents used, treatment regimen, total dosage, identifying number and title of clinical trials (if any), indicators of treatment response, and toxicities experienced during treatment. | 4. Assessed individually for surgery: type, dates, and complications |

| 5. Assessed individually for chemotherapy: whether used, name of drug, dosage, dates, presence of toxicities, and indicators of response | |

| 6. Assessed individually for radiotherapy: whether used, dosage, dates, location/field, presence of toxicities, and indicators of response | |

| 7. Assessed individually for hormone therapy (breast cancer only): whether used, dates, presence of toxicities, and indicators of response | |

| 5. Psychosocial, nutritional, and other supportive services provided. | 8. Whether psychosocial services were provided during treatment |

| 9. Whether nutritional services were provided during treatment | |

| 10. Whether any other supportive services were provided during treatment | |

| 6. Full contact information on treating institutions and key individual providers. | 11. Name of at least one cancer care provider at treating institution |

| i | 12. Contact information for at least one cancer care provider at treating institution |

| 7. Identification of a key point of contact and coordinator of continuing care. | 13. Explicit mention of a person (and contact details) for cancer-related follow-up care |

| Follow-up care plan | |

| 1. The likely course of recovery from treatment toxicities, as well as the need for ongoing health maintenance/adjuvant therapy. | 14. Description of recovery from treatment toxicities that includes any reference to the expected timing of recovery |

| 15. Need for ongoing health maintenance/adjuvant therapy not coded, because interpretation was too broad and appeared to overlap with another category | |

| 2. A description of recommended cancer screening and other periodic testing and examinations, and the schedule on which they should be performed (and who should provide them). | 16. Statement of the need for surveillance for recurrence and second primary cancers |

| 17. Name or specialty of provider who provides surveillance above | |

| 18. Timing of any surveillance tests | |

| 19. Statement of the need for any testing for other conditions for which survivors are potentially at high risk (e.g., cholesterol, DXA, pelvic exams, cardiac monitoring for breast cancer survivors) | |

| 20. Who provides testing for other conditions | |

| 21. Timing of any testing for other cancers | |

| 22. Statement of the need for screening for new cancers (colorectal or cervical cancer screening for age- and sex-appropriate breast cancer survivors; breast cancer or cervical cancer screening for age- and sex-appropriate colorectal cancer survivors) | |

| 23. Who provides screening | |

| 24. Timing of any screening | |

| 3. Information on possible late and long-term effects of treatment and symptoms of such effects. | 25. Description of possible late and long-term effects of treatment, including symptoms of such effects. |

| 4. Information on possible signs of recurrence and second tumors. | 26. Information on possible signs of recurrence and second tumors. |

| 5. Information on the possible effects of cancer on marital/partner relationship, sexual functioning, work, and parenting, and the potential future need for psychosocial support. | 27. Information on any of the following: the possible effects of cancer on marital/partner relationship, sexual functioning, work, or parenting |

| 28.Information on the potential future need for psychosocial support | |

| 6. Information on the potential insurance, employment, and financial consequences of cancer and, as necessary, referral to counseling, legal aid, and financial assistance. | 29. Information on any of the following: the potential insurance, employment, or financial consequences of cancer; or indication of a referral to counseling, legal aid, or financial assistance. |

| 7. Specific recommendations for healthy behaviors (e.g., diet, exercise, healthy weight, sunscreen use, immunizations, smoking cessation, osteoporosis prevention). When appropriate, recommendations that first-degree relatives be informed about their increased risk and the need for cancer screening (e.g., breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer). | 30. Specific recommendations for any healthy behaviors and practices, such as: diet, exercise, healthy weight, smoking cessation, sunscreen use, dental exams, breast self exams, cholesterol screening (for colorectal cancer survivors), and immunizations |

| 31. Potential place for recommendations that first-degree relatives be informed about their increased risk and the need for cancer screening (e.g., breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer) | |

| 8. As appropriate, information on genetic counseling and testing to identify high-risk individuals who could benefit from more comprehensive cancer surveillance, chemoprevention, or risk-reducing surgery. | 32. Potential place for information on genetic counseling and testing to identify high-risk individuals who could benefit from more comprehensive cancer surveillance, chemoprevention, or risk-reducing surgery. |

| 9. As appropriate, information on known effective chemoprevention strategies for secondary prevention (e.g., tamoxifen in women at high risk for breast cancer; aspirin for colorectal cancer prevention). | 33. Potential place for information on known effective chemoprevention strategies for prevention of other cancers (e.g., tamoxifen in women at high risk for breast cancer; aspirin for colorectal cancer prevention) |

| 10. Referrals to specific follow-up care providers (e.g., rehabilitation, fertility, psychology), support groups, and/or the patient's primary care provider. | 34. Mention of referrals to any of the following: specific follow-up care providers (e.g., rehabilitation, fertility, psychology), support groups, or the patient's primary care provider |

| 11. A listing of cancer-related resources and information (e.g., Internet-based sources and telephone listings for major cancer support organizations). | 35. Mention of any of the following cancer-related resources: names of organizations, internet-based sources, and telephone listings for any cancer support organizations |

| Summary measures | |

| Treatment history | 1. Inclusion of tumor characteristics and whether survivor received any treatment from the following list: surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or hormone therapy (breast cancer only) |

| Expectations for survivorship | 2. Description of: late and long-term effects, signs of recurrence, and potential need for psychosocial support |

| Recommendations for ongoing care | 3. Recommendations for cancer screening, cancer surveillance, and healthy behaviors |

| Information about who is responsible for ongoing tests | 4. Explicit mention of who provides the recommended screening tests, surveillance tests, and other tests for conditions for which cancer survivors are at high risk. |

To get a more global picture of the content of SCPs, we further operationalized broader component categories to determine whether SCPs included 1) a treatment history, 2) information about what survivors can expect after treatment completion, 3) recommendations for ongoing care, and 4) information regarding who is responsible for ongoing testing, as defined in Table 2. We excluded IOM-recommended components of SCPs from our review if they were not applicable to survivors of colorectal or breast cancer, such as information about gene therapy or transplantation.

Two authors (TL and TS) independently reviewed every SCP by coding whether it contained each component proposed by the IOM. Components were considered as present in the SCPs if they were explicitly listed or called for in the SCP and as absent if not. Discrepancies between reviews were resolved in discussion. If necessary, we asked the individual at the relevant center who provided us with the SCP clarifying questions. We report proportions of SCPs containing each component of the IOM SCP using all received SCPs as the denominator.

Follow-up survey

In order to better understand how SCPs are used in context, we followed up the receipt of each SCP with a request for five additional pieces of contextual information: when the SCP is provided to survivors, the proportion of eligible patients who receive the SCP, the proportion of breast and colorectal oncology providers who provide SCPs to their patients, whether the SCPs were accompanied by other informational materials, and whether SCPs are provided to survivors with metastatic disease. Survey items asked for multiple-choice responses and also allowed room for additional narrative responses.

Results

Extent of adoption

All 53 NCI-designated cancer centers that treat adult cancer patients responded. The individuals at each institution who provided information were most commonly affiliated with a survivorship program (48%) or oncology services (32%). The remaining individuals came from programs in cancer prevention, cancer education, cancer control, supportive care, and administration. Respondents at 23 of the 53 institutions (43%) reported that they use SCPs for their breast cancer survivors, colorectal cancer survivors, or both. Of these 23 institutions, 17 (74%) reported using SCPs only for breast cancer, 2 (9%) used SCPs only for colorectal cancer, and 4 (17%) used SCPs for both groups of survivors. Of the institutions that did not currently provide SCPs, fifteen (50%) volunteered that they are planning survivorship programs or developing SCPs.

Content of SCPs

Of the 21 centers that use SCPs for breast cancer survivors, 18 submitted SCPs for review that had been developed by the institution, one institution did not share their SCP, and two reported using the ASCO breast cancer SCPs.64 Of the 6 centers that use SCPs for colorectal cancer survivors, 5 used institution-specific SCPs, and 1 used the ASCO colon cancer SCP.65 We reviewed the breast cancer SCPs from 20 institutions and the colorectal SCPs from 6 institutions.

Concordance of SCPs with IOM recommendations

Treatment summary

A basic treatment history was included in 95% of breast SCPs (19 of 20) and 83% of colorectal SCPs (5 of 6) (Table 3). Tumor characteristics were reported in 95% of breast and 83% of colorectal SCPs. A report of the treatments that the patient received was present in most breast SCPs (80% to 95% depending on treatment modality) and colorectal SCPs (67% to 83% depending on treatment type). The level of detail regarding each treatment the patient had received varied widely.

Table 3.

Concordance of survivorship care plans with IOM recommendations (N=20 breast and 6 colorectal cancer plans)

| Components of IOM plan | Breast plans | Colorectal plans |

|---|---|---|

| Present N (%) | Present N(%) | |

| Date of diagnosis | 17 (85) | 5 (83) |

| Tumor characteristics described | 19 (95) | 5 (83) |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Whether used | 19 (95) | 5 (83) |

| Name of drug | 18 (90) | 5 (83) |

| Dose | 14 (70) | 5 (83) |

| Date started | 15 (75) | 4 (67) |

| Date stopped | 16 (80) | 4 (67) |

| Treatment response | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Toxicities | 11 (55) | 4 (67) |

| Radiation | ||

| Whether used | 17 (85) | 4 (67) |

| Dose | 15 (75) | 4 (67) |

| Location | 13 (65) | 4 (67) |

| Date started | 13 (65) | 4 (67) |

| Date stopped | 16 (80) | 4 (67) |

| Treatment response | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Toxicities | 8 (40) | 4 (67) |

| Surgery | ||

| Whether used | 19 (95) | 5 (83) |

| Procedure | 19 (95) | 5 (83) |

| Date | 19 (95) | 4 (67) |

| Complications | 9 (45) | 4 (67) |

| Hormone therapy | ||

| Whether used | 16 (80) | N/A |

| Date started | 14 (70) | N/A |

| Date stopped | 11 (55) | N/A |

| Treatment response | 1 (5) | N/A |

| Toxicities | 6 (30) | N/A |

| Clinical trials | ||

| Whether participated | 8 (40) | 2 (33) |

| Date | 3 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Number and other identifying info | 6 (30) | 1 (17) |

| Psychosocial services provided | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Nutritional services provided | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other supportive services provided | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Name(s) of cancer care provider(s) who treated them | 17 (85) | 5 (83) |

| Contact information for cancer care provider(s) who treated them | 12 (60) | 3 (50) |

| Continuing cancer care key contact | 14 (70) | 3 (50) |

| Contact information for continuing primary care | 9 (45) | 3 (50) |

| Information on when to visit primary care provider | 9 (45) | 2 (33) |

| Likely course of recovery from treatment toxicities | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Recommendation for 2nd primary cancer/recurrence surveillance | 20 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Information regarding who provides 2nd primary surveillance | 10 (50) | 4 (67) |

| Information regarding timing of 2nd primary surveillance | 15 (75) | 6 (100) |

| Recommendation for screening for other cancers | 16 (80) | 4 (67) |

| Information regarding who provides cancer screening | 9 (45) | 1 (17) |

| Information regarding timing of cancer screening | 12 (60) | 3 (50) |

| Recommendation for other tests (cholesterol, anemia) | 9 (45) | 4 (67) |

| Information regarding who provides other tests | 2 (10) | 2 (33) |

| Information on timing of other tests | 7 (35) | 2 (33) |

| Late and long term effects of treatments | 8 (40) | 1 (17) |

| Possible signs of recurrence and second tumors | 13 (65) | 0 (0) |

| Marital/partner, sexual functioning, work, parenting effects | 6 (30) | 2 (33) |

| Potential need for future psychosocial support | 8 (40) | 3 (50) |

| Insurance, employment, legal aid, financial assistance | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Recommendations for healthy behaviors | 14 (70) | 4 (67) |

| Recommendations for relatives’ screening if at increased risk | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Genetic counseling information to identify high risk people | 6 (30) | 1 (17) |

| Information on chemoprevention | 0 (0) | 0(0) |

| Referrals to other providers | 3 (15) | 1(17) |

| Cancer-related resources | 7 (35) | 1 (17) |

| Categories of components | ||

| Treatment history | 19 (95) | 5 (83) |

| Expectations for survivorship experiences | 4 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Recommendations for care | 11 (55) | 3 (50) |

| Information on who is responsible for ongoing testing | 2 (10) | 1 (17) |

Only one breast SCP (5%) and none of the colorectal SCPs included information regarding the psychosocial services the patient received. None of the remaining breast or any of the colorectal SCPs included history of any other supportive services, such as physical therapy and nutritional services.

Follow-up plan

Fifty-five percent of breast SCPs and 50% of colorectal SCPs included basic recommendations for ongoing care. All SCPs included recommendations for monitoring for recurrences, and SCPs commonly included recommendations for screening for other cancers (80% of breast SCPs and 67% of colorectal SCPs). Most SCPs recommended additional testing for conditions for which survivors are high risk (95% of breast SCPs and 67% of colorectal SCPs). However, few SCPs explained which provider would perform all three types of testing (10% of breast SCPs and 17% of colorectal SCPs). Recommendations for healthy behaviors were present in 70% of breast SCPs and 67% of colorectal SCPs.

Few SCPs (20% of breast and 0% of colorectal) provided a basic description of what challenges survivors can expect after completing treatment, ranging from medical late effects to psychological issues. Descriptions of potential late effects associated with the cancer therapy were included in only 40% of breast SCPs and 17% of colorectal SCPs. Sixty-five percent of breast SCPs and none of the colorectal SCPs described possible signs of recurrence and second tumors.

The level of detail regarding the impact of cancer on marital issues, such as sexual function, parenting difficulties, as well as information about insurance, employment, legal aid, and financial assistance was generally low (0% to 33% across disease sites and types of issues). The potential need for psychosocial support was noted in 40% of breast and 50% of colorectal SCPs.

Context of delivery

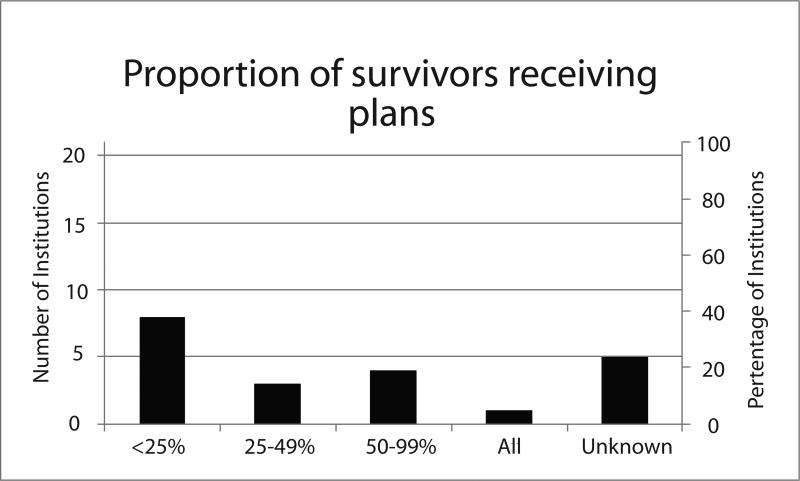

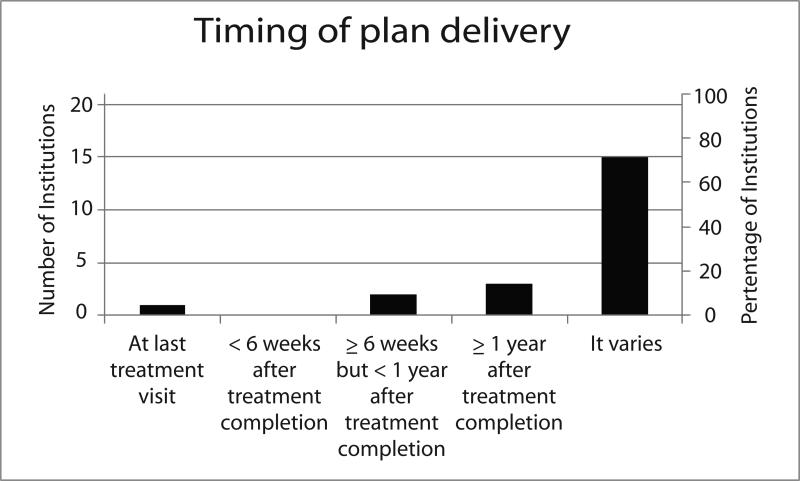

Twenty-one of the 22 institutions (95%) that shared their SCPs or used ASCO SCPs responded to the follow-up survey about the context of SCP delivery. Of the 4 institutions that deliver both breast and colorectal SCPs, representatives from 3 institutions responded to the survey and all reported that the context of SCP delivery was the same for both disease sites. Thus, the results on this endpoint are not stratified by disease site (Figure).

Most respondents (71%) indicated that the timing of SCP delivery varied within the institution, often stating that timing is contingent on when treating clinicians refer survivors (or when survivors refer themselves) to survivorship clinics or programs. Because SCPs are often developed and provided within the context of a separate survivorship visit or clinic rather than by the treating clinicians, and not all survivors transition from treatment to survivorship at the same institution, 24% of respondents were unable to estimate how many patients treated at the institution received SCPs. Among the 16 institutions who were able to estimate the proportion of survivors receiving SCPs, 52% reported that fewer than half of survivors received them. Because SCPs were frequently provided by survivorship nurses rather than treating clinicians, we could not determine the proportion of treating clinicians providing SCPs.

Eighteen respondents (86%) reported providing supplemental educational materials along with the SCP, such as a comprehensive binder or booklet containing a full range of information on topics related to post-cancer care to survivor-specific information and referrals. Respondents volunteered that topics included IOM-recommended information regarding healthy behaviors, nutrition, and screening. Common survivorship materials mentioned by respondents were the NCI's Facing Forward series, the OncoLife web site, and resources from the Lance Armstrong Foundation on nutrition and overall health.

Few institutions (19%) provide SCPs to survivors with metastatic disease and of these, all respondents indicated doing so only rarely.

Conclusion

The use of SCPs has wide support, and survivors and their providers feel they would benefit from SCPs. Despite the enthusiasm for SCPs, our review found that fewer than half of NCI-designated cancer centers provide SCPs to their breast or colorectal cancer survivors. Even within these institutions, most survivors of these cancers do not receive SCPs today. Providing SCPs requires financial resources, time, and institutional commitment. It seems clear that these barriers to the implementation of SCPs will need to be addressed before SCPs are more widely adopted.

We found similarities among SCPs between institutions, which may reflect an implicit consensus on the essential elements to be included in SCPs. Cancer-specific information such as the location and size of the tumor is commonly reported for both cancers, as well as hormone receptor status for breast cancer. Similarly, recommendations to pursue timely surveillance (for second primary cancers and recurrences) and screening for new cancers appeared in almost all SCPs, suggesting that this is universally deemed essential for inclusion in SCPs.

A surprising finding was the limited extent to which SCPs delineated a division of responsibilities between providers. This was particularly salient for screening for second cancers: despite 84% of breast SCPs recommending screening for non-breast cancers, only 42% of SCPs noted which healthcare provider was responsible for screening. Part of the IOM's goal for SCPs was to facilitate the transition from acute cancer care to ongoing preventive care, but existing SCPs appear to have failed to address this issue explicitly.

SCPs rarely included information about legal and financial resources, genetic testing, and screening for relatives, even though these components were also recommended in the IOM report. Although the IOM recommends providing SCPs to patients treated for advanced disease and reporting indicators of treatment response, information about treatment response was universally excluded, and institutions reported that they generally do not provide SCPs to patients with advanced disease.

There was a lack of consistency between the SCPs regarding their inclusion of information about what survivors can expect after treatment completion, including late effects, signs and symptoms of recurrence, and possible psychosocial effects of cancer survivorship. There was also variation in whether healthy behaviors were described and whether external resources for survivors were listed.

We hypothesize that the variation between SCPs is partly due to a difference in the perceived audience. Although the SCP is thought to be a communication tool for both survivors and their primary care providers, satisfying both audiences in one document may prove difficult. Details about legal resources and listings of cancer-related resources, for instance, may obfuscate important medical details for primary care providers. Correspondingly, providing medical details, such as the dosage of chemotherapeutic agents, may confuse survivors who do not know how to act upon such details.

Another cause of variation in content may be due to a lack of clarity within the IOM framework. The IOM suggests including information relevant to patients with advanced disease, which causes some ambiguity about when a SCP should be provided and what treatment history should be included for these patients. Also, some parts of the IOM framework were vague or difficult to understand, such as “Need for ongoing health maintenance/adjuvant therapy,” and may be difficult for clinicians to interpret. Further, the IOM framework has a very wide scope of recommendations for preventive measures, ranging from surveillance for second primary cancers, screening for unrelated cancers, prevention of conditions for which cancer survivors are at high risk, prevention and treatment of psychosocial issues, and prevention of conditions for which cancer survivors are not at higher risk. Beyond these medical recommendations, the IOM framework includes suggestions for other types of support, such as legal and financial resources. While some SCPs addressed most of these recommendations, most SCPs only addressed a small subset. A careful refinement of the elements of the IOM framework may help institutions create SCPs that address only the most important and salient recommendations.

Our review of SCPs is limited by our choice of cancer sites and the sample of institutions. The adoption and content of SCPs for breast and colorectal cancer may not represent SCPs for other cancers. Likewise, NCI-designated cancer centers may not be representative of all cancer programs and practices. However, they may be at the forefront of adopting additional support services for cancer patients. Even in this context, only a minority of these institutions had SCPs in place for colorectal or breast cancer.

Given the sporadic dissemination of SCPs even within institutions, it is possible that some respondents were unaware of SCPs in use at their institutions. Thus, although we attempted to contact key leaders in both oncology services and survivorship programs, we may have undercounted institutions that provide SCPs to their breast and colorectal cancer survivors.

By evaluating only templates for SCPs or de-identified sample SCPs we may have lost information about the true content of SCPs that are given to patients at these institutions. A further limitation is that individual SCPs may appear to lack certain information that may be addressed comprehensively in conversations during office visits or in other printed materials. After all, the vast majority of institutions reported offering additional printed educational information, and some of this material may include some of the components the SCPs appear to lack. Correspondingly, by using the IOM framework as the standard for evaluation, we did not include in this review features that were included in SCPs that went beyond the scope of the IOM framework.

Although the use of SCPs for breast and colorectal cancers at NCI-designated cancer centers is not yet widespread, adoption appears to be underway at many of these institutions. The content of SCPs may be expected to vary to suit the needs of individual institutional settings, but the next challenge is to evaluate and refine the IOM framework and identify the essential components of SCPs. Refining the framework may, in turn, facilitate widespread adoption of SCPs.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Acknowledgments

Source of support: This work was supported by a research grant from the National Cancer Institute (R03-CA- 144682-01).

Footnotes

The authors declare no financial disclosures.

Contributor Information

Talya Salz, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center 307 East 63rd Street New York, NY 10065.

Kevin C. Oeffinger, Director, MSKCC Adult LTFU Program Departments of Pediatrics and Medicine Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center 300 East 66th Street, Office 907 New York, NY 10065.

Mary S. McCabe, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center 1275 York Avenue Room 2001K New York, New York 10065.

Tracy M. Layne, Yale School of Public Health Department of Chronic Disease Epidemiology 60 College St, PO Box 208034 New Haven, CT 06520.

Peter B. Bach, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center 307 East 63rd Street New York, NY 10065.

References

- 1.Cancer survivors --- United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(9):269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973-1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2766–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(17):1322–30. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, et al. It's not over when it's over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors--a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40(2):163–81. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stricker CT, Jacobs LA. Physical late effects in adult cancer survivors. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22(8 Suppl Nurse Ed):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2577–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, et al. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(4):306–20. doi: 10.1002/pon.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D. Breast cancer survival, work, and earnings. J Health Econ. 2002;21(5):757–79. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101(8):1712–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert SM, Miller DC, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Cancer survivorship: challenges and changing paradigms. J Urol. 2008;179(2):431–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: treatment through survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010(40):25–30. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5112–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feuerstein M. The cancer survivorship care plan: health care in the context of cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(3):113–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0934406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganz PA. Quality of care and cancer survivorship: the challenge of implementing the institute of medicine recommendations. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(3):101–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0934402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman B, Stovall E. Survivorship perspectives and advocacy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(32):5154–5159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horning SJ. Follow-up of adult cancer survivors: new paradigms for survivorship care planning. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22(2):201–10. v. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.President's Cancer Panel . Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyajian R. Survivorship treatment summary and care plan: tools to address patient safety issues? Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(5):584–6. doi: 10.1188/09.CJON.584-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bw Hesse, Arora NK, Arora Nk E, Beckjord Burke, Burke Beckjord E LJ, Rutten Finney, et al. Information support for cancer survivors. Fau. Fau. Fau. (0008-543X (Print))

- 22.ASCO Cancer Treatment Summaries. 2011 Available from: http://www.cancer.net/patient/Survivorship/ASCO+Cancer+Treatment+Summaries.

- 23.LIVESTRONG Care Plan powered by Penn Medicine's OncoLink. 2011 Available from: http://www.livestrongcareplan.org/

- 24.American Cancer Society [2011]; Available from: www.cancer.org.

- 25.ASCO's Library of Treatment Plans and Summaries Expands. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4(1):31–36. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0816001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. [2010];Life Beyond Cancer. 2010 Available from: http://www.nccn.com/Life-Beyond-Cancer.aspx.

- 27.A.C.o.S.C.o. Cancer, editor. Cancer program standards 2012: Ensuring patient-centered care. 2011.

- 28.Ayanian J, Jacobsen PB. Enhancing research on cancer survivors. (1527-7755 (Electronic)) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, et al. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: Implications for cancer care. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2(3):179–189. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psychooncology. 2007;16(9):796–804. doi: 10.1002/pon.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brennan ME, Butow P, Marven M, et al. Survivorship care after breast cancer treatment - Experiences and preferences of Australian women. Breast. 2011;20(3):271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burg MA, Lopez ED, Dailey A, et al. The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S467–71. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marbach TJ, Griffie J. Patient preferences concerning treatment plans, survivorship care plans, education, and support services. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(3):335–42. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawkins NA, Pollack LA, Leadbetter S, et al. Informational needs of patients and perceived adequacy of information available before and after treatment of cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2008;26(2):1–16. doi: 10.1300/j077v26n02_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch BM, Youlden D, Fritschi L, et al. Self-reported information on the diagnosis of colorectal cancer was reliable but not necessarily valid. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips KA, Milne RL, Buys S, et al. Agreement between self-reported breast cancer treatment and medical records in a population-based Breast Cancer Family Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4679–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, et al. The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3(2):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, et al. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2270–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller R. Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(3):479–87. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.479-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Royak-Schaler R, Passmore SR, Gadalla S, et al. Exploring patient-physician communication in breast cancer care for African American women following primary treatment. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2008;35(5):836–843. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.836-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith S, Singh-Carlson S, Downie L, et al. Survivors of breast cancer: patient perspectives on survivorship care planning. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, et al. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: Perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(SUPPL. 2):S459–S466. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roundtree AK, Giordano SH, Price A, et al. Problems in transition and quality of care: perspectives of breast cancer survivors. (1433-7339 (Electronic)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, et al. The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2009;3(2):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith SL, Singh-Carlson S, Downie L, et al. Survivors of breast cancer: patient perspectives on survivorship care planning. J Cancer Surviv. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, et al. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor's perspective. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(10):1280–1289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Stricker CT, et al. Delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: the perspective of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):933–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blinder V, Norris V, Peacock N, et al. Patient perspectives on a breast cancer treatment plan/summary program in community oncology care: an ASCO pilot program. Under review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Jacobs LA, Palmer SC, Schwartz LA, et al. Adult cancer survivorship: evolution, research, and planning care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(6):391–410. doi: 10.3322/caac.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chou W.-y., Liu B, Post S, et al. Health-related Internet use among cancer survivors: data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003–2008. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.I.o. Medicine, editor. Implementing Survivorship Care Planning: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: A survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(SUPPL. 18):4409–4418. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, et al. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(20):3338–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nissen MJ, Beran MS, Lee MW, et al. Views of primary care providers on follow-up care of cancer patients. Family Medicine. 2007;39(7):477–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nissen MJ, Beran MS, Lee MW, et al. Views of primary care providers on follow-up care of cancer patients. Fam Med. 2007;39(7):477–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]