Abstract

A member of the SF2 family of helicases, Escherichia coli RecQ is involved in the recombination and repair of double-stranded DNA breaks and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) gaps. Although the unwinding activity of this helicase has been studied biochemically, the mechanism of translocation remains unclear. To this end, using ssDNA of varying lengths, the steady-state ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ was analyzed. We find that the rate of ATP hydrolysis increases with DNA length, reaching a maximum specific activity of 38±2 ATP/RecQ/second. Analysis of the rate of ATP hydrolysis as a function of DNA length implies that the helicase has a processivity of 19±6 nucleotides on ssDNA, and that RecQ requires a minimal translocation site size of 10±1 nucleotides. Using the T4 phage encoded gene 32 protein (G32P), which binds ssDNA cooperatively, to decrease the lengths of ssDNA gaps available for translocation, we observe a decrease in the rate of ATP hydrolysis activity that is related to lattice occupancy. Analysis of the activity in terms of the average gap sizes available to RecQ on the ssDNA coated with G32P indicates that RecQ translocates on ssDNA on average 46±11 nucleotides before dissociating. Moreover, when bound to ssDNA, RecQ hydrolyzes ATP in a cooperative fashion, with a Hill coefficient of 2.1±0.6, suggesting that at least a dimer is required for translocation on ssDNA. We present a kinetic model for translocation by RecQ on ssDNA based on this characterization.

Helicases couple the hydrolysis of ATP to unidirectional movement on single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). Upon encountering double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), these ATP driven motors force the displacement of the opposite strand (1, 2), allowing essential metabolic processes such as DNA recombination, repair, and replication to proceed. Translocation on ssDNA also serves other biological roles such as displacing bound proteins to regulate pathways such as DNA recombination (3–5).

The RecQ helicase from E. coli is a Super-Family 2 (SF2) helicase involved in the repair and recombination of DNA (6, 7). This protein is the founding member of the RecQ protein family of helicases, which is a family of highly conserved motor proteins in bacteria and eukaryotes. recQ was identified as a gene that conferred resistance to thymine-less growth and was found to function in recombinational DNA repair by the RecF pathway (8). RecQ, in conjunction with RecJ, processes DNA at the site of a stalled replisome to allow daughter-strand gap repair and recombination-mediated restart of DNA replication (9). RecQ, a 3′ to 5′ helicase (10), and RecJ, a 5′ to 3′ exonuclease (11), can process double-strand breaks to produce 3′-terminated ssDNA (12). This ssDNA serves as the substrate for assembly of a RecA filament, which then finds homology in intact dsDNA and promotes pairing of the ssDNA to the homologous target.

RecQ has additional roles in DNA recombination and replication. RecQ can disrupt joint molecules both in vivo (13) and in vitro (12, 14). In addition, RecQ can function with Topoisomerase III (Topo III), a type I topoisomerase, to catenate and decatenate dsDNA (15, 16). This reaction can serve two potential functions: one is to dissolve double Holliday junctions formed during recombination (17–20), and the other is to decatenate converged replication forks (21).

In vitro, the RecQ helicase binds to and unwinds a variety of different DNA substrates (10, 14, 22, 23). DNA with an ssDNA tail, gapped DNA, blunt dsDNA and covalently closed dsDNA are all unwound by RecQ, indicating that the helicase can function on a variety of intermediates found in DNA metabolism. RecQ is one of the few helicases that can unwind covalently closed, circular DNA—showing that it does not require a DNA end to enter dsDNA (15, 24). The ssDNA binding protein (SSB) from E. coli interacts with RecQ and stimulates its helicase activity to the extent that RecQ can unwind plasmid-length DNA (21, 24, 25).

Initially, helicase assays performed with plasmid DNA suggested a nearly stoichiometric mechanism for unwinding dsDNA by RecQ (10, 22). In this mechanism, short patches of dsDNA are unwound by RecQ translocation over relatively short distances (24). However, unwinding of dsDNA is stimulated by SSB. In the presences of SSB, optimal unwinding requires 1 RecQ for every 30 base pairs, indicating that each helicase is capable of unwinding a region of DNA longer than its DNA binding site size (24, 26). Furthermore, experiments with dsDNA possessing a 3′-ssDNA tail show that RecQ alone can unwind dsDNA up to 25 base-pairs in length (27).

The translocation mechanism of RecQ, however, has not been studied in as great detail as the unwinding mechanism. Several assays, as well as models, exist for the study of translocation by helicases on ssDNA. Steady-state analysis of several helicases on ssDNA has revealed estimates of processivity, directionality, and sequence effects on translocation (28–30). Kinetic mechanisms of translocation can be elucidated from analysis of the steady-state ATP hydrolysis activity. To understand translocation by RecQ, we studied the steady-state behavior of its ssDNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis activity as a function of DNA length. We find that the activity of RecQ increases with longer lengths of ssDNA. Moreover, when studied on ssDNA that is coated with T4 gene 32 protein (G32P) to limit the size of ssDNA available for activity, ATP hydrolysis was reduced in a manner that is quantitatively consistent with RecQ translocation on the ssDNA gaps that were available. We present a model to describe the mechanism of translocation for RecQ.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Equations and Analysis

Equations 1 and 2 were fit using Prism v.5 (GraphPad Software) using a non-linear least squares (NLLS) fitting algorithm. Equation 3 was fit to the data using Scientist 3.0 (Micromath) by holding the parameters n, Kact, ω, and the DNA concentration fixed, while Vf and Kg were fit using NLLS. The numbers reported are the best fit value and the standard deviation for each parameter. The data are reported as the mean and standard deviation of 2–4 experimentally determined values.

DNA Substrates

All oligonucleotide substrates were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT Coralville, IA) and purified by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12%) using 8 M urea, followed by gel extraction, and then concentration by ethanol precipitation (31). The DNA concentrations were determined using the absorbance of thymidine at 267 nm and an extinction coefficient of 9,600 M−1 cm−1 (31). Poly dT was purchased from Amersham-Pharmacia, and had an average length of 312 nucleotides. An extinction coefficient of 8,520 M−1 cm−1 at 260 nm was used to determine the concentration of DNA in nucleotides (31). Plasmid DNA (pUC19) was purified by conventional alkaline-lysis followed by equilibrium ultracentrifugation in a CsCl-ethidium bromide gradient (31). Purified pUC19 was linearized with HindIII (New England BioLabs) for 1 hour at 37°C using the vendor’s recommended conditions, and purified by phenol extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to verify that the DNA was completely digested by the restriction endonuclease. The DNA concentration was determined using an extinction coefficient of 6,600 M−1 cm−1 and measuring the absorbance at 260 nm (31).

Proteins

RecQ was purified as described (14). The concentration of RecQ was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and using an extinction coefficient of 1.48 × 104 M−1 cm−1 (14). G32P was purified as described (32). An extinction coefficient of 4.13 × 104 M−1 cm−1 was used to measure its concentration (32).

ATP hydrolysis assay

ATP hydrolysis was monitored continuously using a spectrophotometric method where pyruvate kinase couples the formation of ADP to the oxidation of NADH by lactate dehydrogenase (33). An HP8452 Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) was used to measure the absorbance of NADH. Reactions were performed by adding 100 μL of reaction buffer consisting of 25 mM TrisOAc (pH 7.5), 1 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 25 units/mL pyruvate kinase, 25 units/mL lactose dehydrogenase, and 200 μM NADH unless otherwise noted to a quartz spectrophotometric cell (Starna Cells) at 37°. M13 ssDNA, poly dT, poly dA, or oligonucleotide DNA was added at the indicated concentration and incubated for 2 minutes in the reaction buffer. The reaction was started by adding RecQ protein to a final concentration of 100 nM. To measure the activity of RecQ using DNA coated with G32P, poly dT (2 μM) was first added to each cuvette. G32P was then added at the indicated binding density, which was calculated by using a site size of 7.5 nt and cooperativity of 1000 (34). After incubation for 2 minutes, RecQ (100 nM) was added to start the reaction. For the titrations with ATP, 100 nM RecQ and 0.3 μM dT30 (molecules) were added to a reaction buffer that did not contain ATP or Mg(OAc)2. To start the reaction, Mg(OAc)2 and then ATP was added to the solution in a 1:1 ratio at the indicated concentration. The slope of the linear region of each trace was calculated, and multiplied by a conversion factor of 1.02 × 10−4 μM−1 cm−1 to convert to units of nmoles (ATP)·s−1.

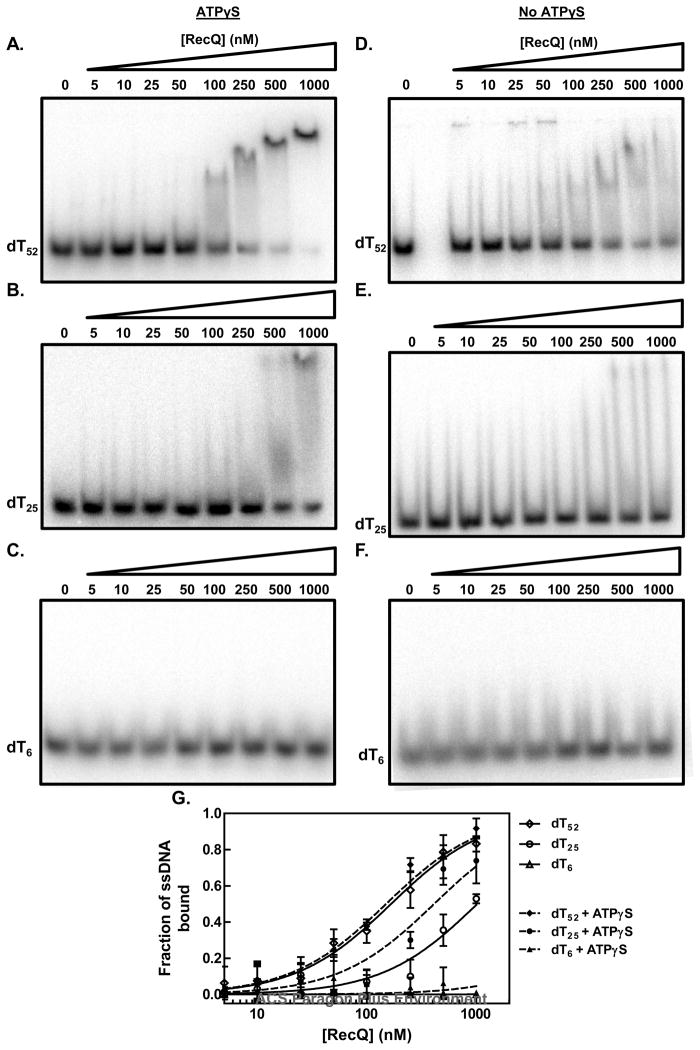

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Oligonucleotides were labeled with 32P using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) at the 5′ end according to the manufacturers specifications. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by a Micro-Spin G25 column (GE Healthcare). Binding of RecQ to short oligonucleotides (5 nM molecules) was carried out in a solution (15 μL) containing 25 mM TrisOAc pH 7.5, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM Mg(OAc)2 with and without 1 mM ATPγS. RecQ (0–1000 nM monomer) was mixed with DNA for 5 minutes at 37°. The RecQ-DNA complexes were mixed with 3 μL of loading buffer (50% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol-blue) and were quickly separated from free DNA using 6% (29:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide ratio) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for dT52 and dT25, and 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for dT6 in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris-borate, 2 mM EDTA). Gels were dried on DE 81 paper (Whatman), exposed to a storage phosphor screen and scanned using a Storm imaging system (Molecular Dynamics). Quantification of free DNA at each concentration of RecQ was calculated using Image-QuaNT software (Version 5.2, G.E. Healthcare) and analyzed as described (35). The dissociation constant, Kd, for RecQ on each DNA substrate was determined by fitting the data to a one-site binding curve, , where Y is the fraction of DNA bound, Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant, and Bmax is the maximum fraction of bound DNA. The value of Bmax was fixed to 1 (mol/mol).

RESULTS

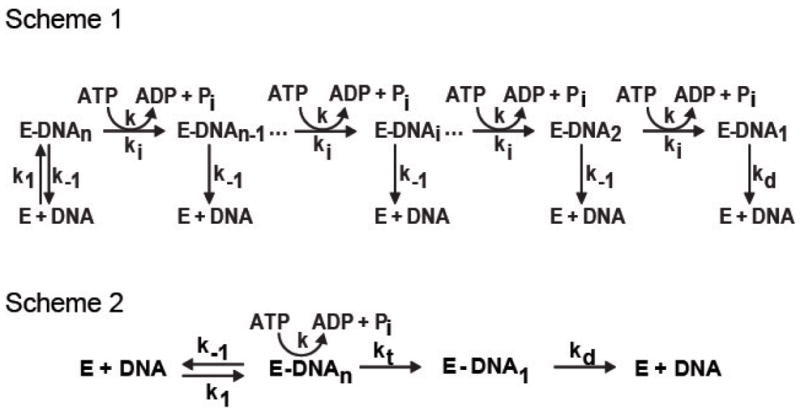

Model that describes ATP hydrolysis by RecQ during translocation on ssDNA

A kinetic theory for the analysis of steady-state ATP hydrolysis by DNA translocases was elaborated by Young et al. (28). In this paper, several models were proposed that gave rise to characteristic dependencies on DNA length of the apparent affinity, or Km, (referred to as the Kact by Young et al.) and the maximum ATP hydrolysis rate. These models provide a useful framework for interpreting ATP hydrolysis and its relationship to the translocation of RecQ on ssDNA. As will be established experimentally below, the model that is depicted in Figure 1 (Scheme 1) is one that is applicable to RecQ. Free RecQ (E) has little or no ATP hydrolysis activity as compared to RecQ bound to ssDNA (E-DNAi where “i” indicates the position along the lattice and “n” is the length of ssDNA in nucleotides). Upon binding ssDNA with a rate constant k1, the helicase undergoes multiple rounds of ATP hydrolysis with rate, k, coupled to translocation. The enzyme moves in discrete steps with a forward rate constant, ki, for translocation. At each step, the helicase can also dissociate from internal DNA sites with a rate constant, k−1. Upon reaching the end of the lattice, the helicase ceases hydrolyzing ATP and dissociates with a rate constant, kd.

Figure 1. Model for translocation on single-stranded DNA by a helicase.

Scheme 1 depicts a helicase-DNA complex, (E-DNA), that undergoes multiple rounds of ATP hydrolysis coupled to translocation on single-stranded DNA. The rate of forward translocation is ki; the rate of dissociation from the internal sites of DNA is k−1; the rate of ATP hydrolysis per translocation step is k; and the rate of dissociation from the end of DNA is kd. The kinetic scheme can be used to derive a model for steady-state ATP hydrolysis by a ssDNA translocase, depicted in scheme 2 (28). In this model, the translocase hydrolyzes ATP as long as it is bound to DNA. Reaching the DNA end, the protein ceases ATP hydrolysis and then dissociates from the end. This model predicts that the maximal velocity of ATP hydrolysis is dependent on DNA length, and that Kact is independent of DNA length.

Scheme 1 can be condensed to Scheme 2, which collapses the translocation steps into a single species, E-DNA. In this simplified scheme, the apparent rate constant for translocation to the end of the ssDNA is represented by an average rate, kt. This average rate is derived by assuming an equal probability of RecQ binding along the length of ssDNA and averaging the rate constant ki over all bound species (28). The amount of ATP hydrolyzed by RecQ is directly proportional to the longevity of the E-DNA species, and hence, to the length of ssDNA. The results, which establish that the translocation of RecQ on ssDNA can be adequately described by the mechanism depicted in Scheme 2, follow.

The ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ depends on the length of ssDNA

The rate of ATP hydrolysis by RecQ was measured as a function of DNA length using ssDNA that was composed solely of thymidine residues of length “n” in nucleotides (dTn). These substrates were used to prevent formation of DNA secondary structure. In Figure 2A, titrations using oligonucleotides of different lengths are shown. A hyperbolic dependence of the ATP hydrolysis rate on DNA concentration was observed. The data were fit to equation 1

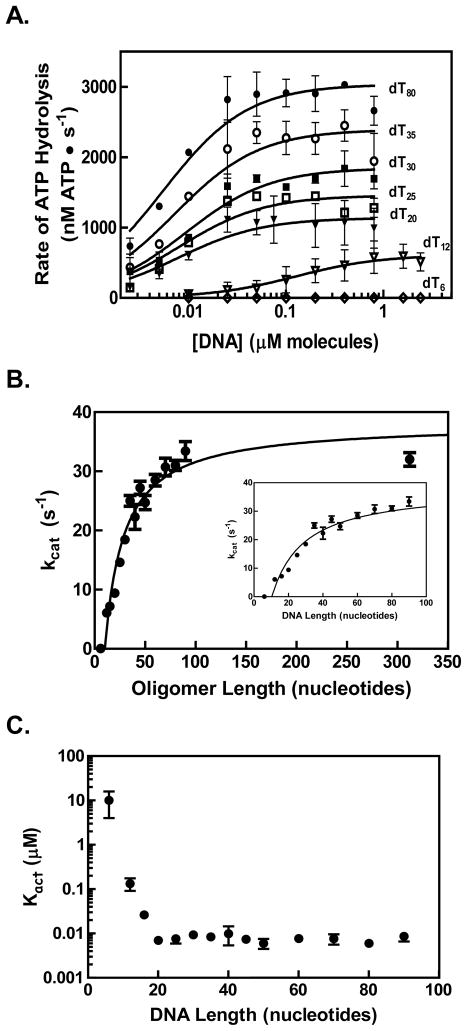

Figure 2. The rate of ATP hydrolysis by RecQ increases for longer DNA substrates.

(A) Representative titrations of RecQ (100 nM) with oligonucleotides (dTn) of various lengths (n) are shown on a semi-log plot. The data were fit to equation 1 in the text (solid lines) to obtain a maximum velocity (Vmax) and a Kact value for each titration. (B) The kcat for ATP hydrolysis by RecQ is plotted as a function the DNA length (black circles). The specific activity (kcat) was determined by dividing the Vmax derived from each oligonucleotide titration by the total RecQ concentration. The data were fit to equation 2 (solid black line). The inset graph is a magnified view showing shorter lengths. (C) Values determined for Kact are plotted against DNA length.

| (1) |

where Vmax is the maximal velocity of ATP hydrolysis, and Kact is the concentration of DNA at which the ATP hydrolysis activity is half of Vmax (28). The maximum velocity for ATP hydrolysis by RecQ increases as DNA length is increased (Figure 2A), however, the 6-mer oligonucleotide stimulated ATP hydrolysis poorly (Figure 2A, open diamonds). The dependence of the observed turnover number for ATP hydrolysis, kcat (Vmax/[RecQ]), and Kact on the length of DNA were plotted as a function of DNA length (Figures 2B and 2C, respectively). For substrates 12 nucleotides or longer, kcat increased in a hyperbolic fashion with DNA length; in contrast, Kact did not vary with DNA length above 12 nucleotides. The dependence of Vmax, but not Kact, on the DNA length is uniquely predicted by the kinetic model presented in Figure 1, which defines an ssDNA translocase that moves along DNA, hydrolyzing ATP with a uniform rate per step, until it reaches a DNA end whereupon it ceases ATP hydrolysis and dissociates with a distinct rate constant, kd (28). Consequently, the data in Figure 2B were fit to equation 2

| (2) |

where Vf is the maximum specific activity; Kg the length of DNA at which the specific activity is one-half of Vf; n the length of the ssDNA substrate; and n0 is the minimum length of DNA for which stimulation of the ATP hydrolysis is observed. Equation 2 is a modification of the equation presented in Young and von Hippel, adding n0 to the equation to account for the minimum DNA length requirement for translocation. We added this parameter due to our observation that a 6-mer did not stimulate the ATP hydrolysis by RecQ; other helicases were also observed to require a minimum DNA length for translocation (36). Fitting of the data in Figure 2B to equation 2 yielded the values Vf = 38±2 s−1; Kg = 19±5 nucleotides; and n0 = 10±1 nucleotides (Table 1). This analysis reveals that after the minimum length of ~10 nts is exceeded, the midpoint for maximal stimulation of ATP hydrolysis by RecQ is ~19 nucleotides.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for translocation by RecQ on ssDNA.a

| Substrate | Vf (s−1) | Kg (nucleotides) | n0 (nucleotides) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotides (dTn) | 38±2 | 19±5 | 10±1 |

| G32P-Poly dT | 32±2 | 46±11 | -- |

The translocation parameters were determined from measurements of steady-state ATP hydrolysis on the indicated substrate. Values for Kg, Vf, and n0 were determined from a fit of equation 2 to the data in Figure 2 for dTn substrates, and from a fit of equation 3 to the data in Figure 5 for G32P-poly dT. All values reported are best fit values with the standard deviation from NLLS fitting

The ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ shows little dependence on the DNA sequence but is cooperative with respect to ATP concentration

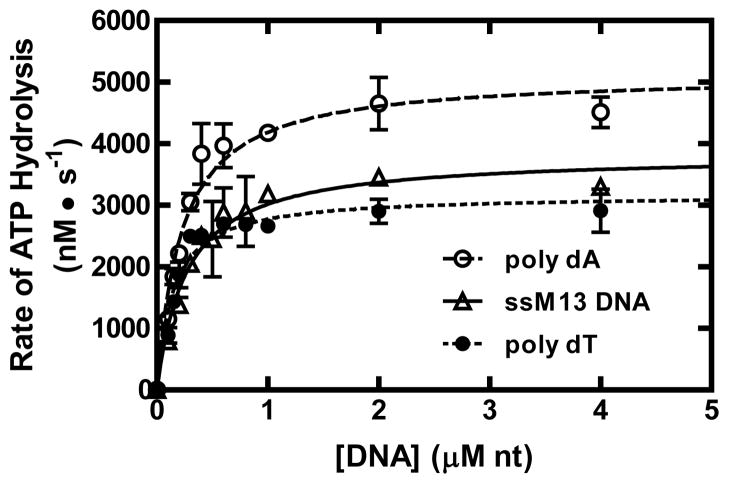

The experiments above measured ATP hydrolysis by RecQ using a homogenous DNA lattice. Normally, RecQ translocates and unwinds dsDNA with a heterogeneous base composition. To determine whether the activity of RecQ is dependent on DNA composition, we measured the steady-state parameters of RecQ using poly dT, poly dA, and M13 ssDNA. Figure 3 shows the titration data for each DNA substrate and the fits to equation 1 (solid curves). The values for each parameter are shown in Table 2. RecQ displays a larger Kact value for poly dA, and M13 ssDNA when compared with poly dT, showing that RecQ displays a modest compositional preference for DNA. The maximum rate of ATP hydrolysis, Vmax, was similar for poly dT, M13 ssDNA, and the dT-containing oligonucleotides; however, it increased slightly when poly dA was the substrate.

Figure 3. The ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ stimulated by different ssDNA substrates.

Titrations of RecQ (100 nM) with poly dA (open circles), M13 ssDNA (open triangles), or poly dT (filled circles) are shown. The data were fit to equation 1 (solid, dashed, and dotted lines), and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for ssDNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis by RecQ.b

| Substrate | Kact (μM nucleotides) | kcat (s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotides (dTn) | 0.4±0.2 | 38±2 |

| Poly dT | 0.14±0.02 | 32±1 |

| M13 ssDNA | 0.27±0.04 | 38±2 |

| Poly dA | 0.22±0.03 | 51±2 |

The parameters values for Kact and kcat were determined from a fit of equation 1 to the data in Figure 2 and Figure 3. For the DNA oligonucleotides, the Kact value reported is the average for all lengths above 12 nucleotides. All values reported are best fit values with the standard deviation from NLLS fitting.

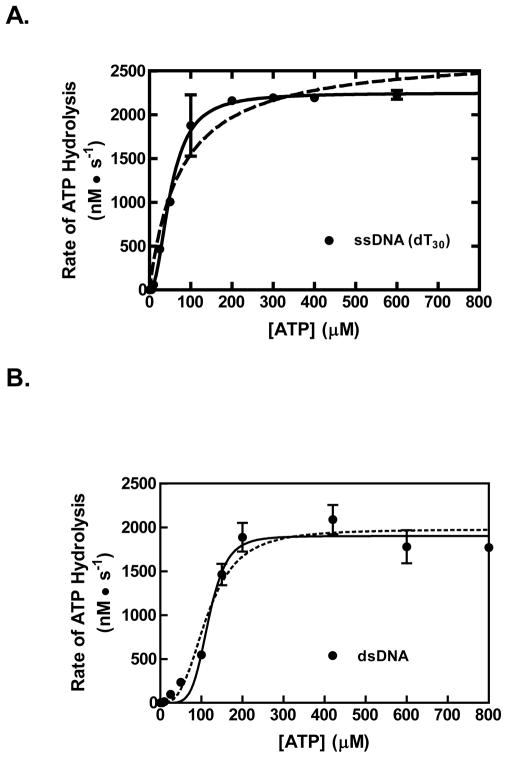

We also examined the effect of the ATP concentration on ssDNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis by RecQ. Figure 4A shows the ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ as a function of ATP concentration at a saturating concentration of dT30. The activity is sigmoidal with respect to the ATP concentration. The Hill equation was used to fit the data, and RecQ was determined to have an apparent Km of 51±4 μM, a kcat of 23±0.6 s−1, and a Hill coefficient of 2.1±0.3. The sigmoidal behavior of the ATP hydrolysis activity and the Hill coefficient implies that RecQ translocates as a dimer or larger on ssDNA.

Figure 4. The ssDNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ is cooperative with respect to ATP concentration.

The rate of ATP hydrolysis by RecQ (100 nM) stimulated by dT30 (0.3 μM, molecules) is plotted as a function of ATP concentration (black circles). The data were fit to the Hill equation (solid line, R2= 0.98). For comparison, a fit to a hyperbolic equation is shown (dashed line, R2= 0.95) (B) The rate of ATP hydrolysis by RecQ (100 nM) stimulated by linear pUC19 (2.5 μM, base pairs) is shown (black circles). The data were fit to the Hill equation (solid curve, r-squared value of 0.98). For comparison, a fit to the Hill equation with the Hill coefficient held constant at 3 is shown (dotted curve, r-squared value of 0.95).

Previously, the unwinding of dsDNA by RecQ was also seen to be cooperative in ATP concentration (with a Hill coefficient of 3.3 ± 0.3) implying that the unwinding species is a trimer or larger (24). We, therefore, tested whether the dsDNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ also shows cooperative behavior with linear pUC19 dsDNA. In Figure 4B, it is clear that the rate of ATP hydrolysis by RecQ shows a sigmoidal dependence on ATP concentration, with Hill equation parameters of 116±5 μM for the Km; 19.0±0.6 s−1 for the kcat; and 5±1 for the Hill coefficient (solid curve). However, it is also evident from the fitting that although the curve passes through the data at the higher ATP concentration, it systematically deviates from the data at low ATP concentrations. Consequently, we also fit the ATP hydrolysis data to the Hill equation, while holding the Hill coefficient constant at 3, which is the value determined from the helicase assays. Such a constrained fit resulted in values of 114±9 μM for the Km and 19±0.7 s−1 for the kcat that are, within error, the same as for the unconstrained fit (Figure 4B, dotted curve), and it is evident that the dotted curve fits the data at low ATP concentration better than the solid line, but now deviates more at the higher ATP concentrations. Because of this systematic deviation, we cannot assign a Hill coefficient with certainty, but he closeness of the two fits using Hill coefficients of 3 and 5 indicates that a minimum of 3 to 5 monomers of RecQ are involved in the unwinding of dsDNA.

G32P blocks ATP hydrolysis by RecQ by limiting translocation on ssDNA

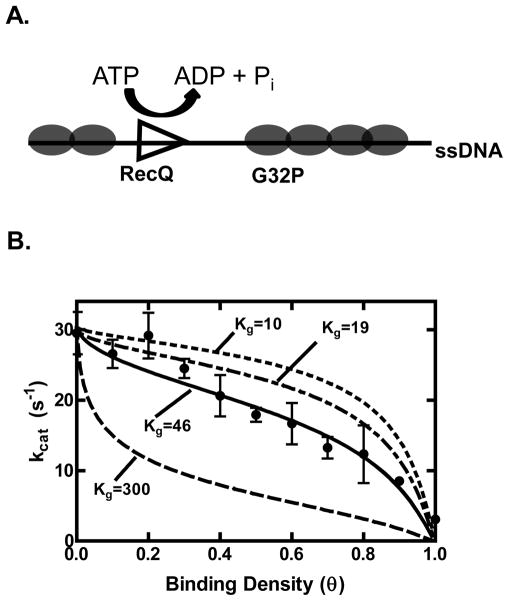

One drawback to the analysis of the ATP hydrolysis activity using short oligonucleotides is that the binding and hydrolysis activity of RecQ may be affected by the DNA ends. To see if the end effects of the short DNA substrates influence the activity of RecQ, we measured the ATP hydrolysis activity on a long ssDNA substrate (poly dT) coated with an ssDNA-binding protein. Provided that RecQ cannot displace the bound ssDNA-binding protein, an ssDNA-binding protein should block ssDNA binding sites and limit translocation, resulting in a decrease in the ATP hydrolysis activity (Figure 5A). We tested this possibility by using T4 phage-encoded gene 32 protein (G32P) because the average gap size and, thus, track length can be accurately calculated using the formalism of McGhee and von Hippel from its known equilibrium binding constants and cooperativity parameters (34, 37). Equation 3 describes the dependence of the ATP hydrolysis rate (V) on the concentration of DNA and ssDNA-binding protein (28).

Figure 5. G32P inhibits the ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ by creating short gaps of ssDNA.

(A) Diagram of the experiment. Increasing the binding density (θ) decreases the lengths of ssDNA available for RecQ binding and translocation. (B) The rate of ATP hydrolysis by RecQ (100 nM) stimulated by poly dT (2 μM) is plotted as a function of increasing concentrations of G32P (black circles). The data from θ = 0 to 0.9 were fit using equation 3 (solid line), and values of 32±2 s−1 and 46±11 nucleotides were obtained for Vf and Kg, respectively. Also shown are simulations of equation 3 with the value of Vf set to 32 s−1 and Kg set to either 10, 19 or 300 nucleotides (dashed lines). The turnover number for θ = 1 was obtained by adding G32P at 1 μM (3.75-fold in excess of the ssDNA).

| (3) |

In equation 3, θ is the binding density (moles of ligand per moles of lattice divided by the site size of the enzyme); Vf is the maximum ATP hydrolysis activity; Kact is the concentration of DNA at which the velocity is one half of Vf; Kg is the length of DNA at which the ATP hydrolysis activity is half of Vf; and Gav is the average gap size. Gav is calculated using equation 4

| (4) |

where θ is the binding density; ω is the cooperativity parameter; n is the site size of the single-strand DNA binding protein (in nucleotides) and R is given below.

Poly dT was incubated with increasing concentrations of G32P. With increasing binding density of G32P (θ), the ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ decreased as shown in Figure 5B. The fact that that ATP hydrolysis by RecQ is decreased by 10-fold (32 to 3 s-1) when the binding density of the poly dT by G32P approaches saturation, implies that RecQ does not displace the bound G32P, consistent with an assumption of the model. The data were fit to equation 3, which determines the activity as a function of binding density. In the fits, the site size, n and cooperativity parameter, ω, were fixed using the values of 7.5 nucleotides and 1000 respectively, which were previously determined as the thermodynamic parameters describe the binding of G32P to poly dT (34). The non-linear least square fit of equation 3 is shown as a solid black curve, with corresponding parameters Vf and Kg of 32±2 s−1 and 46±11 nucleotides, respectively (Table 1). Additionally, for comparison, simulations are shown (dashed line) for the hypothetical cases of a translocase with a Kg (apparent processivity) of 10 nucleotides, 19 nucleotides, or 300 nucleotides. Given the assumptions and the many parameters involved, the best fit value for Kg determined by this independent procedure is quite close to that obtained from analysis of the ssDNA length-dependence of ATPase activity, although it is slightly larger.

RecQ does not bind short ssDNA

From the kinetic analysis, we observed that a 6-mer of ssDNA did not efficiently stimulate ATP hydrolysis; consequently, we wished to know whether the ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ was not being activated by the 6-mer, or whether RecQ simply could not bind such a short oligonucleotide. To distinguish between these possibilities, we measured the affinity of RecQ for different oligonucleotide substrates using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Figure 6). We observed that although RecQ could bind and shift the mobility of these substrates, the complexes dissociated appreciably during electrophoresis; therefore, the free DNA in each lane was quantified (35). In the absence of ATP, we observed that RecQ binds to the longer oligonucleotide, dT52, with an apparent affinity (Kd = 170±10 nM) that is greater than for a shorter oligonucleotide, dT25, (Kd = 1000±100 nM), but that it did not bind to dT6 (Figure 6D–F). Addition of the non-hydrolysable ATP analog, adenosine 5′-O-(3-thio) triphosphate (ATPγS), (instead of ATP to permit an equilibrium measurement) did not detectably affect the already high apparent affinity for dT52 (Kd = 150±20 nM), but it did increase the affinity of RecQ for dT25 by 2.5-fold (Kd = 400±60 nM); there was still no detectable binding to dT6 (Figure 5A–C). The increase in the apparent affinity induced by ATPγS binding is consistent with the ~2-fold increase elicited by adenosine 5′-(beta, gamma-imido) triphosphate (AMPPNP) reported previously (26). Our results clearly show that RecQ does not bind a 6-mer with sufficient affinity to stimulate ATP hydrolysis.

Figure 6. The apparent affinity of RecQ for ssDNA is dependent on the lattice length.

The apparent affinity of RecQ for oligonucleotides was assayed by using the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. (A–C) in the presence of ATPγS; (D–F) in the absence of any nucleotide cofactor; (G) quantification of the disappearance of free DNA relative to the intensity of DNA lane without RecQ: the absence of nucleotide cofactor (open symbols) or presence of ATPγS (filled symbols). The apparent binding constant, Kd, was determined for each DNA substrate by fitting the data to the equation for a one-site binding curve. The fitted curves are shown for each substrate in the absence of a nucleotide cofactor (solid lines) or presence of ATPγS (dashed lines).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of the steady-state ssDNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis by RecQ is consistent with the translocation mechanism as depicted in Scheme 1. RecQ binds and translocates along the ssDNA, coupling ATP hydrolysis to each kinetic step. Upon reaching the end of the ssDNA, RecQ ceases to hydrolyze ATP, and then dissociates from the end with a distinct rate constant. This mechanism gives rise to the characteristic dependence of Vmax, but not Kact, on DNA length (28). In contrast, potential alternative mechanisms for translocation by RecQ that can be disregarded are distinguished by which of the two parameters, Vmax and Kact, depend on DNA length. If RecQ were to dissociate from the DNA end with the same rate constant as for dissociation from any internal site (i.e., k−1), then this mechanism would predict a decrease in Kact (i.e., an increase in apparent affinity) with increasing DNA length but no change in Vmax (28). On the other hand, if RecQ were to dissociate from the DNA end with a unique rate constant (i.e., kd) but, rather than ceasing ATP hydrolysis in this state it continued hydrolyzing ATP unproductively at the end, then such a mechanism would result in both Vmax and Kact being dependent on the DNA length (28, 30). Therefore, based on our observation that Vmax, but not Kact, is dependent on the length of DNA, we conclude that RecQ translocates via the mechanism depicted in Scheme 1.

The data and our analysis indicate that RecQ translocates with modest processivity. In deriving equation 2, the parameter Kg can be expressed as the rate constant for translocation and dissociation (28), as given by equation 5.

| (5) |

Thus, Kg is proportional to the ratio of the translocation rate constant, ki, and the dissociation rate constant, k−1, providing an estimate for the processivity of RecQ. The value for Kg indicates that RecQ moves on average 19±6 nucleotides before dissociating from ssDNA. In addition, analysis of the ATP hydrolysis activity on G32P-coated ssDNA indicates that the helicase translocates 46±11 nucleotides before dissociating. This independent determination of the processivity is higher than the value determined from the titration with oligonucleotides. This difference in the values implies either that DNA ends may influence the binding to and translocation on ssDNA by RecQ or that dissociation from an ssDNA gap defined by bound G32P may be kinetically different than dissociation from an ssDNA end. All assumptions considered, the values are quite compatible, and they are similar to the value for the average number of nucleotides translocated by RecQ determined of 36±2 nucleotides determined from the pre-steady state kinetic experiments (38).

From the ssDNA length-dependence, we observed that stimulation of ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ requires approximately 10 nucleotides. This value is in reasonable agreement with previous studies measuring ATP hydrolysis activity that showed RecQ bound to ssDNA with a site size of 6 nucleotides (24). In comparison, UvrD requires a length of 8 nucleotides for translocation, whereas PcrA requires only 5 nucleotides (39, 40). In our experiments, a 6-mer (dT6) slightly stimulated the ATP hydrolysis activity of RecQ. On the other hand, the 12-mer, dT12, stimulated ATP hydrolysis activity in a hyperbolic fashion. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays showed that RecQ binds shorter lengths of ssDNA poorly compared to longer ones: RecQ cannot bind dT6 either in the absence or presence of the non-hydrolysable ATP analogue ATPγS. The translocation site size of 10 nucleotides may reflect a minimum binding site size of the helicase on ssDNA (26). A similar translocation site size was determined for UvrD in kinetic studies (41). In seeming contradiction, pre-steady-steady translocation assays show that RecQ requires a minimum site of 34±4 nucleotides for translocation (38). But the electrophoretic mobility shift assays show that RecQ binds with a high apparent affinity (150–170 nM) to dT52 and that this affinity is unaffected by ATPγS. However, for dT25, the apparent affinity is much lower (~1 μM) in the absence of ATP, but in the presence of ATPγS, the apparent affinity increases to ~0.4 μM. These findings imply that in the pre-steady-state kinetic experiments, wherein RecQ is pre-mixed with ssDNA in the absence of ATP, the enzyme cannot bind to DNA shorter than 30 nucleotides and thus is quickly bound by quenching agent (heparin), rationalizing the kinetic observations.

The translocation processivity of RecQ (19–46 nucleotides) is low compared to the processivity of other helicases translocating on ssDNA, but it is also consistent with the amount of dsDNA unwound by RecQ under optimal stead-state conditions (30 base pairs per RecQ monomer) (24, 26). The superfamily 1 (SF1) helicases UvrD and PcrA translocate on average 700 and 300 nucleotides on ssDNA, respectively, before dissociating from ssDNA (41, 42). These values are ten-fold higher than the processivity of RecQ. On the other hand, the S. cerevisiae chromatin remodeling complex Isw2, a member of Superfamily 2, displays a processivity similar to that of RecQ (43). Isw2 was found to travel 20 nucleotides on ssDNA before dissociating. The similarity of the processivity of RecQ to another SF2 ssDNA translocase may reflect a structural and biochemical features shared by SF2, but not SF1, helicases. SF1 helicases bind ssDNA by making contacts with the phosphate backbone and individual base pairs (2, 44). On the other hand, SF2 helicases bind to ssDNA using primarily only the phosphate backbone.

Interestingly, the processivity of several SF2 translocases that translocate on dsDNA, rather than ssDNA, is very different when compared to RecQ. S. cerevisiae Rad54 and Tid1/Rdh54 are chromatin and protein-DNA remodeling complexes, and members of the SF2 superfamily. Rad54 translocates on average 10,000 base pairs, while Tid1 moves on average 5,000 base pairs, before dissociating from the dsDNA (45, 46). On the other hand, S. cerevisiae RSC, which is also remodels chromatin, has a processivity similar to RecQ, moving only 20 base pairs before dissociating (47). These examples underscore the mechanistic differences that arise between helicases within the same superfamily likely due to the role each protein plays in the cell.

We observed a Hill coefficient of 2.1±0.3 for the ATP hydrolysis stimulated by ssDNA, indicating that a minimum of 2 subunits of RecQ are involved in ssDNA translocation. In contrast, for dsDNA, the Hill coefficient is 3–5. Thus, the minimal size of RecQ for translocating on ssDNA is at least a dimer, whereas the minimal size for unwinding is at least a trimer and maybe even a pentamer or greater. Why oligomerization by a helicase is necessary for translocation ssDNA is unclear. The mechanism for translocation by Isw2 and RSC includes a slow step prior to steady-state ATP hydrolysis and movement (43, 47). A similar slow step is not observed with RecQ, indicating that binding to ssDNA and forming an oligomer is rapid and the kinetically slow step occurs during translocation (38). A dimer may be required to bind and translocate on ssDNA, while 3 dimers of RecQ may interact or coordinate to unwind dsDNA. Single-turnover experiments measuring the unwinding activity of RecQ on dsDNA substrates with an ssDNA tail show that while a monomer can unwind dsDNA, it cannot unwind more than 25 base pairs (27). These observations support our view that even though a monomer may be competent for DNA unwinding, an oligomeric form of RecQ is need for the efficient unwinding of longer tracts of dsDNA. Finally, these ideas derived, from ensemble data, are also consistent with recent single-molecule analysis of DNA unwinding by RecQ (48), further validating the general utility of the much simpler steady-state ensemble experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kowalczykowski laboratory for helpful comments, and especially Ichiro Amitani, James Graham, and Katsumi Morimatsu for their careful reading of this manuscript.

The abbreviations used are

- ATPγS

adenosine 5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate

- AMPPNP

adenosine 5′-(beta, gamma-imido) triphosphate

- dsDNA

double-stranded DNA

- G32P

gene 32 protein

- SSB

single-stranded DNA binding protein

- ssDNA

single-stranded DNA

- Topo III

Topoisomerase III

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM41347 to S.C.K.; B.R. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health training grant T32-GM007377.

References

- 1.von Hippel PH, Delagoutte E. A general model for nucleic acid helicases and their “coupling” within macromolecular machines. Cell. 2001;104:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singleton MR, Dillingham MS, Wigley DB. Structure and mechanism of helicases and nucleic acid translocases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.115300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veaute X, Jeusset J, Soustelle C, Kowalczykowski SC, Le Cam E, Fabre F. The Srs2 helicase prevents recombination by disrupting Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments. Nature. 2003;423:309–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antony E, Tomko EJ, Xiao Q, Krejci L, Lohman TM, Ellenberger T. Srs2 disassembles Rad51 filaments by a protein-protein interaction triggering ATP turnover and dissociation of Rad51 from DNA. Mol Cell. 2009;35:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krejci L, Van Komen S, Li Y, Villemain J, Reddy MS, Klein H, Ellenberger T, Sung P. DNA helicase Srs2 disrupts the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Nature. 2003;423:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature01577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakayama H. RecQ family helicases: roles as tumor suppressor proteins. Oncogene. 2002;21:9008–9021. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakayama H. Escherichia coli RecQ helicase: a player in thymineless death. Mutat Res. 2005;577:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakayama H, Nakayama K, Nakayama R, Irino N, Nakayama Y, Hanawalt PC. Isolation and genetic characterization of a thymineless death-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K-12: Identification of a new mutation (recQ1) that blocks the recF recombination pathway. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;195:474–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00341449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courcelle J, Hanawalt PC. RecQ and RecJ process blocked replication forks prior to the resumption of replication in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:543–551. doi: 10.1007/s004380051116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umezu K, Nakayama K, Nakayama H. Escherichia coli RecQ protein is a DNA helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5363–5367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovett ST, Kolodner RD. Identification and purification of a single-stranded-DNA-specific exonuclease encoded by the recJ gene of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2627–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handa N, Morimatsu K, Lovett ST, Kowalczykowski SC. Reconstitution of initial steps of dsDNA break repair by the RecF pathway of E. coli. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1234–1245. doi: 10.1101/gad.1780709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanada K, Ukita T, Kohno Y, Saito K, Kato J, Ikeda H. RecQ DNA helicase is a suppressor of illegitimate recombination in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3860–3865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harmon FG, Kowalczykowski SC. RecQ helicase, in concert with RecA and SSB proteins, initiates and disrupts DNA recombination. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1134–1144. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.8.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harmon FG, Brockman JP, Kowalczykowski SC. RecQ helicase stimulates both DNA catenation and changes in DNA topology by topoisomerase III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42668–42678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harmon FG, DiGate RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. RecQ helicase and topoisomerase III comprise a novel DNA strand passage function: a conserved mechanism for control of DNA recombination. Mol Cell. 1999;3:611–620. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: caretakers of the genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:169–178. doi: 10.1038/nrc1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Hickson ID. The Bloom’s syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003;426:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plank JL, Wu J, Hsieh TS. Topoisomerase III and Bloom’s helicase can resolve a mobile double Holliday junction substrate through convergent branch migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11118–11123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604873103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cejka P, Plank JL, Bachrati CZ, Hickson ID, Kowalczykowski SC. Rmi1 stimulates decatenation of double Holliday junctions during dissolution by Sgs1-Top3. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1377–1382. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suski C, Marians KJ. Resolution of converging replication forks by RecQ and topoisomerase III. Mol Cell. 2008;30:779–789. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umezu K, Nakayama H. RecQ DNA helicase of Escherichia coli. Characterization of the helix-unwinding activity with emphasis on the effect of single-stranded DNA-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:1145–1150. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hishida T, Han YW, Shibata T, Kubota Y, Ishino Y, Iwasaki H, Shinagawa H. Role of the Escherichia coli RecQ DNA helicase in SOS signaling and genome stabilization at stalled replication forks. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1886–1897. doi: 10.1101/gad.1223804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harmon FG, Kowalczykowski SC. Biochemical characterization of the DNA helicase activity of the Escherichia coli RecQ helicase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:232–243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shereda RD, Bernstein DA, Keck JL. A central role for SSB in Escherichia coli RecQ DNA helicase function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19247–19258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dou SX, Wang PY, Xu HQ, Xi XG. The DNA binding properties of the Escherichia coli RecQ helicase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6354–6363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang XD, Dou SX, Xie P, Hu JS, Wang PY, Xi XG. Escherichia coli RecQ is a rapid, efficient, and monomeric helicase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12655–12663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young MC, Kuhl SB, von Hippel PH. Kinetic theory of ATP-driven translocases on one-dimensional polymer lattices. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1436–1446. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young MC, Schultz DE, Ring D, von Hippel PH. Kinetic parameters of the translocation of bacteriophage T4 gene 41 protein helicase on single-stranded DNA. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1447–1458. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raney KD, Benkovic SJ. Bacteriophage T4 Dda helicase translocates in a unidirectional fashion on single-stranded DNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22236–22242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bittner M, Burke RL, Alberts BM. Purification of the T4 gene 32 protein free from detectable deoxyribonuclease activities. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9565–9572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panuska JR, Goldthwait DA. A DNA-dependent ATPase from T4-infected E. coli Purification and properties of a 63,000-Dalton enzyme and its conversion to a 22,000-Dalton form. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:5208–5214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kowalczykowski SC, Lonberg N, Newport JW, Paul LS, von Hippel PH. On the thermodynamics and kinetics of the cooperative binding of bacteriophage T4-coded gene 32 (helix destabilizing) protein to nucleic acid lattices. Biophys J. 1980;32:403–418. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)84964-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carey J. Gel retardation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:103–117. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08010-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer CJ, Lohman TM. ATP-dependent translocation of proteins along single-stranded DNA: models and methods of analysis of pre-steady state kinetics. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:1265–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGhee JD, von Hippel PH. Theoretical aspects of DNA-protein interactions: co-operative and non-co-operative binding of large ligands to a one-dimensional homogeneous lattice. J Mol Biol. 1974;86:469–489. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rad B, Kowalczykowski SC. Efficient coupling of ATP hydrolysis to translocation by RecQ helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1443–1448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119952109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dillingham MS, Wigley DB, Webb MR. Demonstration of unidirectional single-stranded DNA translocation by PcrA helicase: measurement of step size and translocation speed. Biochemistry. 2000;39:205–212. doi: 10.1021/bi992105o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomko EJ, Fischer CJ, Niedziela-Majka A, Lohman TM. A nonuniform stepping mechanism for E. coli UvrD monomer translocation along single-stranded DNA. Mol Cell. 2007;26:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer CJ, Maluf NK, Lohman TM. Mechanism of ATP-dependent translocation of E. coli UvrD monomers along single-stranded DNA. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:1287–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niedziela-Majka A, Chesnik MA, Tomko EJ, Lohman TM. Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA monomer is a single-stranded DNA translocase but not a processive helicase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27076–27085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer CJ, Yamada K, Fitzgerald DJ. Kinetic mechanism for single-stranded DNA binding and translocation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Isw2. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2960–2968. doi: 10.1021/bi8021153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pyle AM. Translocation and unwinding mechanisms of RNA and DNA helicases. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:317–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nimonkar AV, Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Single molecule imaging of Tid1/Rdh54, a Rad54 homolog that translocates on duplex DNA and can disrupt joint molecules. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30776–30784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Visualization of Rad54, a chromatin remodeling protein, translocating on single DNA molecules. Mol Cell. 2006;23:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fischer CJ, Saha A, Cairns BR. Kinetic model for the ATP-dependent translocation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RSC along double-stranded DNA. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12416–12426. doi: 10.1021/bi700930n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rad B. Graduate Group in Biophysics. University of California; Davis: 2010. Tracking the RecQ helicase on DNA: An insight into the mechanism of molecular motors; p. 194. [Google Scholar]