Abstract

Objective

To examine trajectories of depressive symptoms in caregivers of critically ill adults from ICU admission to 2 months post-ICU discharge and explore patient and caregiver characteristics associated with differing trajectories.

Design

Longitudinal descriptive

Setting

Medical ICU in a tertiary university hospital

Subjects

50 caregivers and 47 patients on mechanical ventilation for ≥ 4 days

Intervention

None

Measurements and Main Results

Caregivers completed measures assessing depressive symptoms (Short version Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale 10-items [shortened CES-D]), burden (Brief Zarit Burden Interview [Zarit-12]) and health risk behaviors (caregiver health behaviors) during ICU admission, at ICU discharge and 2 months post-ICU discharge. Group-based trajectory analysis was used to identify patterns of change in shortened CES-D scores over time. Two trajectory groups emerged: 1) caregivers who had clinically significant depressive symptoms (21.0 ± 4.1) during ICU admission that remained high (13.6 ± 5) at 2 months post-ICU discharge (high trajectory group, 56%) and 2) caregivers who reported scores that were lower (10.6 ± 5.7) during ICU admission and decreased further (5.7 ± 3.6) at 2 months post-ICU discharge (low trajectory group, 44%). Caregivers in the high trajectory group tended to be younger, female, adult child living with financial difficulty and less likely to report a religious background or preference. More caregivers in the high trajectory group reported greater burden and more health risk behaviors at all time points; patients tended to be male with poorer functional ability at ICU discharge. Caregivers’ responses during ICU admission did not differ in regard to number of days patients being on mechanical ventilation prior to enrollment.

Conclusion

Findings suggest two patterns of depressive symptom response in caregivers of critically ill adults on mechanical ventilation from ICU admission to two months post-ICU discharge. Future studies are necessary to confirm these findings and implications for providing caregiver support.

Keywords: adults critical care, mechanical ventilation, family caregivers, depressive symptoms, trajectories, burden, caregiver health behaviors

INTRODUCTION

Scientific advances have improved survival during ICU admission; however, there is growing concern about life after ICU discharge1,2. For many ICU survivors, recovery is associated with high rates of mortality, disability, and physical and psychological morbidity3–5. This outcome is a growing concern because each year approximately 800,000 Americans receive mechanical ventilation during critical illness6. The majority are older adults (52%), living with one or more comorbid conditions (45%), many of whom (41%) require prolonged support from mechanical ventilation (≥ 4 days) prior to regaining the ability to breathe independently6. Family caregivers provide substantial support over the course of critical illness and recovery, which can place caregivers themselves under substantial psychological and physical stress7–11.

Emotional distress in family caregivers is often manifested as symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and complicated grief12. Such symptoms have been associated with an increased risk of psychological morbidities13–17, an outcome that can affect family caregivers’ physical health and the quality of care they provide. In prior studies, symptoms of depression were highly prevalent in family caregivers during ICU admission15,18–21 and continued after discharge8,9,22,23. When family caregivers were followed for 12 months after an ICU admission requiring mechanical ventilation, 23% reported clinically significant depressive symptoms at 12 months - a rate considerably higher than the rate reported for the general population (16%)9,24. In a study that interviewed 41 family caregivers at various times over 3–12 months after the death of a patient in the ICU, more than one-third reported at least one psychiatric illness, including major depression (27%), generalized anxiety (10%), and/or a panic disorder (10%)17. In some studies, the discharge destination after ICU and the patients’ functional dependency were important predictors of family caregivers’ depressive symptoms, although findings have been inconsistent across studies9,22.

While it is known that depressive symptoms are common in family caregivers9,10,22,25, few studies have explored patterns of stress response in caregivers during and following ICU admission. Trajectory analysis offers the potential to better understand stress responses in family caregivers, identify caregivers who are at greater risk, and suggest approaches to develop supportive interventions.

In this pilot study, we examined trajectories of depressive symptoms in family caregivers of critically ill adults on mechanical ventilation for ≥ 4 days from ICU admission to 2 months post-ICU discharge. We also explored characteristics associated with differing trajectories of depressive symptoms in family caregivers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective longitudinal descriptive design was used. Participants were recruited in a medical ICU in a tertiary university hospital in Western Pennsylvania. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board. All caregivers provided informed consent. If able, patients provided informed consent. Otherwise, proxy consent was obtained from caregivers.

Caregivers were defined as the individual who provided the majority of emotional, financial, and physical support for the patient. No legal relation or cohabitation with the patient was required26. Caregiver eligibility criteria were: 1) non-professional, non-paid caregiver; 2) age ≥ 21 years; 3) reliable telephone access; and 4) able to read and speak English. Caregivers were excluded if they provided care for two or more family members other than children under 21 years old. Patient eligibility criteria were: 1) age ≥ 21 years; 2) residing at home prior to ICU admission; 3) required mechanical ventilation for ≥ 4 consecutive days; and 4) no history of being dependent on mechanical ventilation prior to this admission. We selected mechanical ventilation for ≥ 4 consecutive days due to its clinical relevance, reflecting the average duration of mechanical ventilation following ICU admission27.

Caregivers provided data at three time points: 1) during ICU admission; 2) ICU discharge; and 3) 2 months post-ICU discharge. Data were obtained via a face-to-face or telephone interview, depending on preference. Patient data were obtained from the medical records.

Measures

Shortened Version of Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression 10 items (Shortened CES-D) 28 was used to measure depressive symptoms. The Shortened CES-D used a 4-point Likert-type summative scale (ranges 0–30); higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms. Scores of ≥ 8 have been used as a cutoff to indicate clinically significant depressive symptoms29. Validity has been established in caregivers and healthy adults30,31.

Brief Zarit Burden Interview12 items (Zarit-12)32 was used to measure caregiver burden. Items in the Zarit-12 described feelings due to caregiving (for example, feeling strained) using a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranges 0–48); higher scores indicated greater burden. Scores of ≥ 17 have been used as a cutoff to indicate substantial burden32. Validity in prediction of depressive symptoms has been reported in caregivers of community-dwelling elderly33.

Caregiver Health Behavior (CHB) was used to measure self-reported health risk behaviors among caregivers34. The CHB consisted of 11 items (6 items relating to unhealthy behaviors and 5 items relating to lack of preventive behaviors). Respondents checked the presence or absence of each behavior. The CHB has been used in several population based studies34,35. In these studies, more health risk behaviors were correlated with a higher level of care demands35.

Caregiver characteristics included sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, etc.), difficulty in paying for needs and past history of being seen by health care professionals due to emotional problems.

Activities of Daily Living (ADL)36 and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL)37 were used to determine patients’ functional status. Caregivers were asked to answer questions based upon patient status two weeks prior to ICU admission. Limited ADL or IADL was defined as: not limited (no impairment in ADL or IADL), and limited (at least one or more impairment in ADL or IADL).

Patient characteristics collected from medical records included sociodemographic characteristics, primary diagnosis, Charlson comorbidity score, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and ICU length of stay.

Data Analysis

In order to identify distinct patterns of person-centered trajectories of caregivers’ depressive symptoms and explore relevant factors associated with different depressive symptom trajectories38,39, a semi-parametric trajectory polynomial trend censored multiple regression analysis was performed on shortened CES-D by time (ICU admission, ICU discharge, 2 months post-ICU discharge) using the PROC TRAJ macro in SAS version 9.1. (SAS Institute; Cary, NC, USA)39. Group-based trajectory models were designed to identify clusters of individuals following a similar progression of some behavior or outcome over age or time40. In our analysis, we explored three models based on groups with 2, 3 and 4 different trajectories and estimated linear and quadratic trends for each model. The final model with two trajectory groups with linear trend was selected based on Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), statistical significance of polynomial term and optimal number of trajectory groups which balance the interests of parsimony with the objective of reporting the distinctive developmental patterns. The objective of model selection is not the maximization of some statistic of model fit; rather, it is to summarize the distinctive features of the data in a fashion as parsimonious as possible39.

We chose group-based trajectory analysis over standard longitudinal data modeling, because standard longitudinal data modeling approaches are useful for studying research questions where all individuals come from a single population and a single growth trajectory can adequately approximate an entire population. For research questions about developmental trajectories that can be inherently categorical (e.g. do certain type people tend to have distinctive developmental trajectories?) the group-based approach is considered to be a better suited approach. A particular advantage of this method is that it accommodates incomplete data using maximum likelihood estimation when the data are assumed to be missing at random. The model selection is based on the comparison of the BIC of different models as well as parsimony consideration39. Because this pilot study was conducted in a small sample, we explored different trends in patient and caregiver characteristics by trajectory group instead of identifying predictors of group membership. The Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare characteristics of patients and caregivers between trajectory groups. For the Mann-Whitney U test, the absolute value of r was used to report effect sizes: 0.10 (small), 0.30 (moderate), and 0.50 (large)41. For the Fisher’s exact test, phi-coefficient was used to report effect sizes: 0.10 (small), 0.30 (moderate), and 0.50 (large) 41.

Although all patients enrolled in the study required mechanical ventilation for ≥ 4 days, recruitment occurred at varying intervals (range 4–48 days) following ICU admission. To explore the potential influence of this variation on caregiver response, 3 groups were formed based on the time of recruitment following ICU admission (≤5 days, 6–15 days, > 15 days). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine if there is a difference in depressive symptoms, burden or health risk behaviors by time of recruitment.

To explore patterns of missing data, we compared attrition rate between the two trajectory groups. We also compared scores of shortened CES-D, Zarit-12 and CHB during ICU admission between those who completed the 2 months follow-up and those lost to attrition (e.g. patient death, withdrawal) and differences in characteristics of caregivers and patients lost to attrition using independent sample t-tests or chi-square tests, as appropriate.

Data were analyzed using SAS version, 9.1. (SAS Institute; Cary, NC, USA) and PASW Statistics version 18.0. (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). Results were reported as mean and standard deviations or numbers and percentages. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

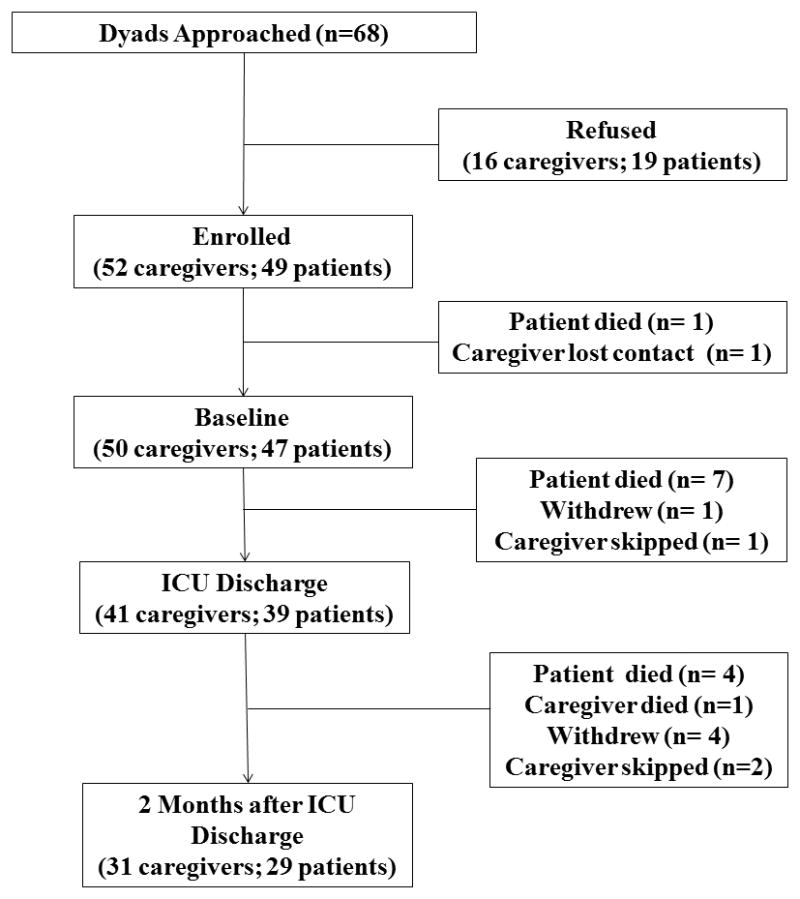

Between November 2008 and July 2010, 68 patient/caregiver dyads were approached. Informed consent was obtained from 52 (76%) caregivers and 49 (72%) patients (Figure 1). The most common reason for refusal was “too much stress.” Baseline data were collected from 50 caregivers and 47 patients after deleting two dyads due to patient death before baseline data collection.

Figure 1.

Sample enrollment and retention

During the 2 months follow-up, attrition occurred due to patient death (n=11), caregiver death (n=1) or inability to contact/withdrawal (n=5). One caregiver skipped data collection at ICU discharge and two skipped data collection at 2 months. Attrition rates were not significantly different between the two trajectory groups (36% high depressive symptom trajectory; 41% low depressive symptom trajectory, χ2 (1) = 0.14, p=0.77). There was no significant difference in any measured variable between caregivers/patients who remained in the study and those who lost to attrition, except with patient age. The patients lost to attrition were significantly older (61.8 ± 15.7 years) than those who completed the 2 months follow-up (51.5 ± 16.3 years, t (45) = −2.1, p= 0.04).

Caregivers were mostly Caucasian (92%), female (74%) with a mean age of 52.3 ± 11.8 years (Table 1). Most were a spouse/significant other (58%) who lived with the patient prior to ICU admission (70%). Most caregivers worked full or part-time (54%). Forty percent (n=20) of caregivers reported a history of being seen by a professional to treat emotional problems. Patients were mostly Caucasian (93.6 %), male (66%) with a mean age of 55.5 ± 16.7 years (Table 2). The most common reason for admission was pulmonary (for example, acute respiratory failure). Prior to ICU admission, 26% (n=12) of patients had at least one limitation in ADL and 40% (n=19) had limited IADL.

Table 1.

Caregiver Characteristics (n=50)

| Characteristics | Total, n=50 no (%) or Mean ± SD | Trajectory Group | p | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low, n=22 no (%) or Mean ± SD | High, n=28 no (%) or Mean ± SD | ||||

| Age, yr | 52.3 ± 11.8 | 55.9 ± 11.5 | 49.4 ± 11.5 | 0.04 b | 0.29 |

| Education, yrs | 14.5 ± 3.3 | 15.2 ± 3.7 | 13.9 ± 2.9 | 0.22b | 0.17 |

| Female gender | 37 (74.0) | 12 (55) | 25 (89) | 0.009a | 0.39 |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 46 (92.0) | 19 (86) | 27 (96) | 0.31a | 0.18 |

| Relationship to patient | 0.02a | 0.40 | |||

| Spouse or significant other | 29 (58.0) | 13 (59) | 16 (57) | ||

| Adult child | 12 (24.0) | 2 (9) | 10 (36) | ||

| Parent or sibling | 9 (17.9) | 7 (32) | 2 (7) | ||

| Income ≥ $ 50,000/yr | 24 (48.0) | 11(50) | 13 (46) | 1.00a | 0.04 |

| Financial difficulty | 0.01a | 0.38 | |||

| Not at all difficult | 28 (56.0) | 17 (77) | 11 (39) | ||

| Somewhat/extremely difficult | 22 (44.0) | 5 (23) | 17 (61) | ||

| Religious background/preference | 41 (82.0) | 21 (95.5) | 20 (71.4) | 0.03a | 0.31 |

| Lived with patient prior to ICU | 35 (70.0) | 16 (73) | 19 (68) | 0.77a | 0.05 |

| Employed full or part time | 27 (54.0) | 12 (54.5) | 15 (53.6) | 1.00a | 0.01 |

| Health insurance | 45 (90.0) | 21 (96) | 24 (86) | 0.37a | 0.16 |

| History of emotional problem | 20 (40.0) | 7 (32) | 13 (46) | 0.39a | 0.15 |

ICU, intensive care unit

Fisher’s exact test

Mann-Whitney U test

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics (n=47)

| Characteristics | Total, n=47 no (%) or Mean ± SD | Trajectory group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low, n=20 no (%) or Mean ± SD | High, n=27 no (%) or Mean ± SD | p | Effect Size | ||

| Age, yr, | 55.5 ± 16.7 | 51.4 ± 17.9 | 58.4 ± 15.5 | 0.26b | 0.16 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | 4.1 ± 3.3 | 3.7 ± 3.8 | 4.4 ± 2.9 | 0.27b | 0.16 |

| APACHE II score, | 21.6 ± 8.0 | 19.9 ± 7.7 | 21.6 ± 8.0 | 0.18b | 0.20 |

| ICU length of stay, days | 22.9 ± 13.7 | 19.7 ± 11.5 | 25.4 ± 15.0 | 0.20b | 0.19 |

| Male gender | 31 (66.0) | 10 (50) | 21 (78) | 0.07a | 0.29 |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 44 (93.6) | 18 (90) | 26 (96) | 0.57a | 0.13 |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Respiratory | 26 (55.3) | 9 (45) | 17(63) | 0.70a | 0.18 |

| Sepsis, Multisystem failure | 9 (19.1) | 5 (25) | 4 (15) | ||

| Gastrointestinal, Hepatic | 8 (17.0) | 4 (20) | 4 (15) | ||

| Others | 4 (8.5) | 2 (10) | 2 (7) | ||

| Limited ADL | |||||

| Prior to ICU admission | 12 (26) | 6 (30) | 6 (22) | 0.74a | 0.07 |

| ICU discharge* | 33 (85) | 11 (73) | 22 (92) | 0.18a | 0.25 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge ^ | 12 (41) | 3 (30) | 9 (47) | 0.27a | 0.22 |

| Limited IADL | |||||

| Prior to ICU admission | 19 (40) | 8 (36) | 11 (39) | 1.00a | 0.03 |

| ICU discharge* | 36 (92) | 12 (80) | 24 (100) | 0.05a | 0.36 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge ^ | 19 (66) | 5 (50) | 14 (74) | 0.11a | 0.33 |

ICU, intensive care unit; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ADL, Activities in Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities in Daily Living

Functional status data were available in 39 patients at ICU discharge: 15 patients in the low trajectory group and 24 in the high trajectory group.

Functional status data were available in 29 patients 2 months after ICU discharge: 11 in the low trajectory group and 18 in the high trajectory group.

Fisher’s exact test

Mann-Whitney U test

Prevalence of depressive symptoms

In our caregivers, the shortened CES-D score during ICU admission was 16.4 ± 7.1 (mean ± SD), which was highest for all three time points. The mean shortened CES-D score decreased over time (10.5 ± 5.9, ICU discharge; 10.3 ± 5.9, 2 months post-ICU discharge). At all three time points, mean shortened CES-D scores were above the cut off score (≥8) indicating clinically significant depressive symptoms. During ICU admission, 90% of caregivers had shortened CES-D score greater than the cut off and the majority (61%) had scores above this value 2 months post-ICU discharge (Table 4). The proportion reporting high burden (Zarit-12 scores ≥ 17) was equivalent during ICU admission and 2 months post ICU discharge (36%) and slightly higher (49%) at ICU discharge. Health risk behaviors were similar at all three time points.

Table 4.

Caregiver depressive symptoms, burden, and health risk behaviors by days on mechanical ventilation prior to interview

| Caregiver responses | Days on mechanical ventilation prior to interview, n=47 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4–5 days, n=13 | 6–15 days, n=22 | >15 days, n=12 | p | |

| Shortened CES-D, Mean ± SD | 15.38 ± 8.6 | 18.0 ± 6.5 | 15.5 ± 6.7 | 0.74b |

| ≥8, no (%) | 10 (76.9) | 21 (95.5) | 11 (91.7) | 0.22a |

| Zarit-12, Mean ± SD | 13.1 ± 7.6 | 14.5 ± 7.2 | 13.7 ± 7.1 | 0.87b |

| ≥17, no (%) | 3 (23.1) | 9 (40.9) | 4 (33.3) | 0.56a |

| CHB, Mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 2.5 | 3.8 ± 2.3 | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 0.94b |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; Zarit-12, Brief Zarit Burden Interview 12-items; CHB, Caregiver Health Behavior

Fisher’s exact test

Kruskal-Wallis test

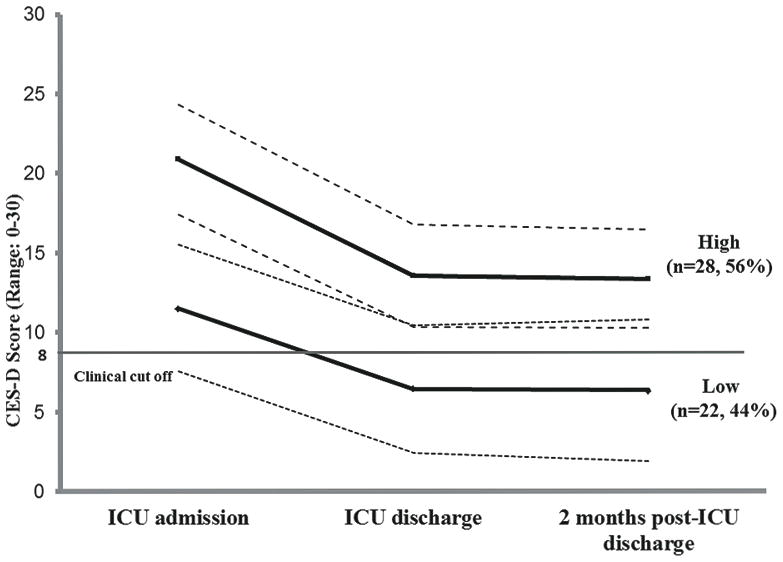

Trajectories of change in caregiver depressive symptoms

Two distinct trajectory groups emerged (Figure 2 and Table 3). During ICU admission, approximately half (56%) of caregivers reported scores that reflected being at risk for clinically significant depressive symptoms (21.0 ± 4.1) and remained high (13.6 ± 5) at 2 months post-ICU discharge (high trajectory group). The remainder reported scores that were lower during ICU admission (10.6 ± 5.7) and decreased further (5.7 ± 3.6) at 2 months post-ICU discharge (low trajectory group). Each group had a significantly different score at all three time points.

Figure 2.

Trajectory of caregiver depressive symptoms. Two group trajectories were identified. In the high trajectory group, CES-D scores were above the cut-off (≥ 8) during ICU admission and remained above this level through two months post-ICU discharge. In the low trajectory group, CES-D scores were above the cut-off (≥8) during ICU admission but decreased below cut-off through two months post-ICU discharge. Solid dark lines = mean scores; dotted lines = 95% confidence interval.

Table 3.

Caregiver depressive symptoms, burden and health risk behaviors over time, stratified by trajectory

| Caregiver responses | Total, n=50 | Trajectory group | p | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low, n=22 | High, n=28 | ||||

| Shortened CES-D ≥8, no (%) | |||||

| ICU admission | 45 (90) | 17 (77) | 28 (100) | 0.01a | 0.38 |

| ICU discharge* | 30 (73) | 6 (38) | 24 (96) | <0.001a | 0.64 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge^ | 19 (61) | 4 (31) | 15 (83) | 0.008a | 0.53 |

| Zarit-12 ≥17, no (%) | |||||

| ICU admission | 18 (36) | 3 (14) | 15 (54) | 0.007a | 0.41 |

| ICU discharge* | 20 (49) | 5 (31) | 15 (60) | 0.111a | 0.28 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge^ | 11 (36) | 3 (23) | 8 (44) | 0.275a | 0.22 |

| CHB, Mean ± SD | |||||

| ICU admission | 3.8 ± 2.3 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 4.8 ± 2.2 | <0.001b | 0.51 |

| ICU discharge* | 3.3 ± 2.4 | 2.3 ± 2.3 | 4.0 ± 2.2 | 0.019b | 0.33 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge^ | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 3.2 ± 2.5 | 0.021b | 0.33 |

ICU, intensive care unit; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; Zarit-12, Brief Zarit Burden Interview 12-items; CHB, Caregiver Health Behavior

Data were available in 41 caregivers patients at ICU discharge:

31 caregivers at 2 months post-ICU discharge.

Because Shortened CES-D was measured during ICU admission, no baseline was established in our sample.

Fisher’s exact test

Mann-Whitney U test

Family caregivers in the high trajectory group tended to be younger in age (p=0.04), female gender (p<.01), an adult child of the patient (p=.02) and report financial difficulty (p=.01). They also reported more health risk behaviors and a higher level of burden at all three time points compared with family caregivers in the low trajectory group (See Table 3). More caregivers in the low trajectory group reported having a religious background or preference (p=0.03).

Difference in caregiver responses by time of enrollment

No significant differences were found in family caregiver responses as a consequence of the time they were recruited into the study after ICU admission (4–5 days, 6–15 days, > 15 days). In each subgroup, mean shortened CES-D scores were above the cutoff. Similarly, mean Zarit-12 scores were close to the cutoff indicating high burden. Mean CHB scores did not show any significant difference between groups (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first study to explore differing patterns of response in depressive symptoms over time in caregivers of critically ill patients who received mechanical ventilation 4 days or longer in a medical ICU. We also explored characteristics associated with the likelihood of higher depressive symptoms trajectory in caregivers. Our study had two main findings. First, it suggested that there may be two distinct patterns of depressive symptom response in caregivers – symptoms consistent with a high risk of clinically significant depressive symptoms during and 2 months after ICU discharge (high trajectory group), and symptoms that were less initially and then decline further over time (low trajectory group). In the high trajectory group, caregiver burden and health risk behaviors were also high and patients tended to have more functional limitations at ICU discharge. Second, caregivers’ depressive symptoms, burden or health risk behaviors during ICU admission appeared to be similar regardless of the time of recruitment into the study.

Our results require cautious interpretation. Because enrollment of caregivers and initial measurements of depressive symptoms occurred during ICU admission, no true baseline data for depressive symptoms were available. Given the small sample size, we did not adjust for patient characteristics or other potential confounders. We recommend future exploration in a larger sample that allows adjustment for important patient and caregiver characteristics.

Consistent with previous studies8,13,18,23, depressive symptoms were highly prevalent in caregivers during ICU admission and after ICU discharge. Despite a decrease in reports of depressive symptoms over time, overall mean scores of shortened CES-D remained higher than community-dwelling elderly spouse caregivers, a group who are often identified as being at high risk for poor physical and mental health outcomes29. Of note, 61% (19 out of 31) of caregivers who responded at the 2 months measurement reported scores greater than the cutoff. Of these, 15 (79%) were in the high trajectory group.

We compared differences in caregiver and patient characteristics in the two symptom trajectory groups in an attempt to identify characteristics that may potentially signal greater risk in family caregivers. In the high depressive symptom trajectory group, patients showed trends of older age, more comorbidities, higher APACHE II score, longer ICU length of stay, respiratory problems as the primary diagnosis, and more ADL and IADL limitations. However, none of these trends were statistically significant. Distinct characteristics of caregivers in the high depressive symptom trajectory group included being female, younger in age, an adult child of the patient and reporting more financial difficulty. Additionally, burden and health risk behaviors were more prevalent among caregivers in the high trajectory group. A large proportion of caregivers in the low trajectory group reported having a religious background or preference. A protective effect of religion or spirituality on psychological and physical functioning and coping with stress has been suggested42–44. Because we asked a single global question about religious background or preference, our data do not permit us to address differences in religious coping, a complex multidimensional construct45,46, in explaining trajectories of caregiver responses. However, our findings are consistent with those of Ford and colleagues, who reported that religion and/or faith is associated with positive illness experience, less emotional impact and better confidence in patients and family surrogates during ICU admission47. Future studies should take a more fine-grained approach to studying the role of religious coping in this context.

The ability to identify predictors may aid designing supportive interventions. For example, the role of caregiver gender and relationship to patient needs further examination. In future studies, it may also be fruitful to examine the relationship between patients’ recovery trajectory (for example, disposition, weaning from mechanical ventilation, and changes in functional status) and caregivers’ depressive symptom trajectory.

Despite efforts to enroll eligible caregivers early after ICU admission, the first interview occurred at various times after ICU admission. Because prior studies obtained data within 3–7 days after ICU admission18,19,20, we examined, post-hoc, whether responses differed as a consequence of the number of days exposed to the ICU environment. In our study, mean scores of shortened CES-D, Zarit-12 and CHB did not differ over time regardless of the number of days following ICU admission. This suggests that stress levels might be high prior to ICU admission and ICU admission may not provoke a significant increase in emotional distress. While admission to the ICU is a highly stressful experience, it may be possible that it represents a portion of a continuum for those who provide care wherein stress levels are consistently above norms. This finding must be interpreted with caution as our sample size was small and depressive symptoms and burden showed some variation, especially for those interviewed later in the admission.

A recent systematic review suggested patients’ quality of life after ICU discharge is greatly affected by patients’ baseline quality of life prior to the episode of critical illness, not merely from ICU related factors 48. Because more patients with chronic health conditions are admitted to the ICU, it may be particularly important to examine caregivers’ pre-existing stress levels and changes in this response before, during and after the episode of critical illness49,50. We speculate that stress-related symptoms attributed to ICU admission may have predated admission, although perhaps in a less severe manner. If so, stress related to the ICU admission could be overestimated. Additionally, needs of caregivers early in the admission may be under-recognized or underestimated. Our study design did not allow us to determine whether high levels of depressive symptoms in these caregivers could be attributed to current ICU admission, stress related to providing care in the outpatient setting or caregivers’ pre-existing mental health issues.

Notably, 40% of caregivers in the present study reported being seen by health care professionals for emotional problems. This suggests the presence of additional, potentially under-recognized risk factors. A prior history of major depression has been reported as a potent risk factor of major depression triggered by stressful life events51. Because we enrolled caregivers during ICU admission without knowing baseline shortened CES-D scores or prior medical history, our data are limited to self-reports. A major limitation is that we were unable to examine the role of past diagnosis of major depression in explaining trajectories. Studies using qualitative methodology may be necessary to fully explore underlying mechanisms for the development of depressive symptoms, higher burden and health risk behaviors.

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting study findings. First, our sample size was small and therefore did not allow us to examine predictors of trajectory groups. Instead, we provided profiles to illustrate caregiver and patient characteristics consistent with high and low trajectory group membership. Second, our assessment relied on self-reports rather than assessment from mental health professionals. Third, our sample was recruited from a single medical center and was not diverse. A multicenter study involving a larger sample with varied ethnic and racial backgrounds would be necessary for better generalizability. Fourth, like prior studies targeting ICU caregivers, selection bias may exist. Caregivers who were under extreme stress may have refused enrollment. Therefore, our findings likely underestimated caregiver stress. Finally, we elected to use the 10-item version of CES-D. Validity of the 10-item version of CES-D has been confirmed in community dwelling elders31 but not in ICU caregivers.

CONCLUSION

This study found two distinct trajectories of depressive symptoms that were present during ICU admission and continued through 2 months post-ICU discharge. In the high trajectory group, depressive symptoms were initially high and remained so 2 months after ICU discharge. In the low trajectory group, depressive symptoms were initially high but decreased over time. Caregivers’ depressive symptoms, burden or health risk behaviors did not differ in regard to the time of recruitment into the study, suggesting that pre-existing stressors may have been, in part, responsible for the depressive symptoms, burden, and health risk behaviors reported by caregivers. Studies using qualitative methodology may be necessary to fully explore underlying mechanisms for the development of different response patterns in caregivers of the critically ill over the trajectory of ICU admission and recovery.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted at University of Pittsburgh and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian University Hospital, in Pittsburgh, PA

Funding source: This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (F32 NR 011271 and T32 NR 008857) and by Fellow Research Award from Rehabilitation Nursing Foundation (FEL-0905)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None reported

Contributor Information

JiYeon Choi, Department of Acute & Tertiary Care, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Paula R. Sherwood, Department of Acute & Tertiary Care & Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing & School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA.

Richard Schulz, University Center for Social and Urban Research & Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA.

Dianxu Ren, Department of Health & Community Systems, Department of Biostatistics, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing & Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, PA.

Michael P. Donahoe, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy & Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Director, Medical Intensive Care Unit, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian, University Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Barbara Given, Michigan State University College of Nursing, East Lansing, MI.

Leslie A. Hoffman, School of Nursing & Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

References

- 1.Spragg RG, Bernard GR, Checkley W, et al. Beyond mortality: future clinical research in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(10):1121–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0024WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(3):368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, Carson SS. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(4):446–454. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0210CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daly BJ, Rudy EB, Thompson KS, Happ MB. Development of a special care unit for chronically critically ill patients. Heart Lung. 1991;20(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard K, Raffin TA. The chronically critically ill: to save or let die? Respir Care. 1985;30(5):339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Hartman ME, Milbrandt EB, Kahn JM. The epidemiology of mechanical ventilation use in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10):1947–1953. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ef4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi J, Donahoe MP, Zullo TG, Hoffman LA. Caregivers of the chronically critically ill after discharge from the intensive care unit: six months’ experience. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(1):12–22. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011243. quiz 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglas SL, Daly BJ. Caregivers of long-term ventilator patients: physical and psychological outcomes. Chest. 2003;123(4):1073–1081. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Qin L, et al. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(2):167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Pelt DC, Schulz R, Chelluri L, Pinsky MR. Patient-specific, time-varying predictors of post-ICU informal caregiver burden: the caregiver outcomes after ICU discharge project. Chest. 2010;137(1):88–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:000–000. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. Epub 2011 Nov 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2009;137(2):280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2005;20(1):90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, Loseth DB, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1722–1728. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAdam JL, Dracup KA, White DB, Fontaine DK, Puntillo KA. Symptom experiences of family members of intensive care unit patients at high risk for dying. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(4):1078–1085. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cf6d94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paparrigopoulos T, Melissaki A, Efthymiou A, et al. Short-term psychological impact on family members of intensive care unit patients. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(5):719–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickman RL, Jr, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Clochesy JM. Informational coping style and depressive symptoms in family decision makers. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(5):410–420. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, O’Toole E, Hickman RL., Jr Depression among white and nonwhite caregivers of the chronically critically ill. J Crit Care. 2009;25(2):364, e311–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im K, Belle SH, Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Chelluri L. Prevalence and outcomes of caregiving after prolonged (> or =48 hours) mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest. 2004;125(2):597–606. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed February 22, 2011.];Anxiety and Depression. 2009 http://www.cdc.gov/Features/dsBRFSSDepressionAnxiety/

- 25.Douglas SL, Daly BJ. Caregiving and long-term mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2004;126(4):1387. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1387. author reply 1387–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi J. Caregivers of Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: Mind-Body Interaction Model. University of Pittsburgh: Grant # F32 NR011271: National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Health; 2009–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn JM, Goss CH, Heagerty PJ, Kramer AA, O’Brien CR, Rubenfeld GD. Hospital volume and the outcomes of mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz R, Beach SR, Lind B, et al. Involvement in caregiving and adjustment to death of a spouse: findings from the caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 2001;285(24):3123–3129. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logsdon RG, Teri L. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease patients: caregivers as surrogate reporters. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(2):150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Rourke N, Tuokko HA. Psychometric properties of an abridged version of The Zarit Burden Interview within a representative Canadian caregiver sample. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):121–127. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, Burton L, Hirsch C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: the caregiver health effects study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(2):110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burton LC, Newsom JT, Schulz R, Hirsch CH, German PS. Preventive health behaviors among spousal caregivers. Prev Med. 1997;26(2):162–169. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10(1):20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder A. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectorires. Sociological Methods and Research. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagin D. Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones BL, Nagin D. Advances in Group-Based Trajectory Modeling and SAS Procedure for Estimating Then. Sociological Methods and Research. 2007;35(4):542–571. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Field A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 2. Sage publications Ltd; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koenig HG, George LK, Titus P. Religion, spirituality, and health in medically ill hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(4):554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tartaro J, Luecken LJ, Gunn HE. Exploring heart and soul: effects of religiosity/spirituality and gender on blood pressure and cortisol stress responses. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(6):753–766. doi: 10.1177/1359105305057311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(6):700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rabinowitz YG, Hartlaub MG, Saenz EC, Thompson LW, Gallagher-Thompson D. Is religious coping associated with cumulative health risk? An examination of religious coping styles and health behavior patterns in Alzheimer’s dementia caregivers. J Relig Health. 2010;49(4):498–512. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabinowitz YG, Mausbach BT, Atkinson PJ, Gallagher-Thompson D. The relationship between religiosity and health behaviors in female caregivers of older adults with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(6):788–798. doi: 10.1080/13607860903046446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ford D, Zapka J, Gebregziabher M, Yang C, Sterba K. Factors associated with illness perception among critically ill patients and surrogates. Chest. 2010;138(1):59–67. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, Annemans L, Decruyenaere JM. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(12):2386–2400. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3dec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGrath S, Chatterjee F, Whiteley C, Ostermann M. ICU and 6-month outcome of oncology patients in the intensive care unit. QJM. 2010;103(6):397–403. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Miranda S, Pochard F, Chaize M, et al. Postintensive care unit psychological burden in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and informal caregivers: A multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(1):112–118. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feb824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kendler KS, Myers J, Halberstadt LJ. Should the diagnosis of major depression be made independent of or dependent upon the psychosocial context? Psychol Med. 2010;40(5):771–780. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]