Abstract

Little is known about the longitudinal relationship of hopelessness to attempted suicide in psychotic disorders. The present study addresses this gap by assessing hopelessness and attempted suicide at multiple time-points over 10-years in a first-admission cohort with psychosis (n=414). Approximately 1 in 5 participants attempted suicide during the 10-year follow-up, and those who attempted suicide scored significantly higher at baseline on the Beck Hopelessness Scale. In general, a given assessment of hopelessness (i.e., baseline, 6-months, 24-months, and 48-months) reliably predicted attempted suicide up to 4–6 years later, but not beyond. Structural equation modeling indicated that hopelessness prospectively predicted attempted suicide even when controlling for previous attempts. Notably, a cut-point of 3 or greater on the Beck Hopelessness Scale yielded sensitivity and specificity values similar to those found in non-psychotic populations using a cut-point of 9. Results suggest that hopelessness in individuals with psychotic disorders confers information about suicide risk above and beyond history of attempted suicide. Moreover, in comparison to non-psychotic populations, even relatively modest levels of hopelessness appear to confer risk for suicide in psychotic disorders.

Suicide is among the leading causes of death worldwide (Nock, Borges, Bromet et al, 2008), and the World Health Organization (WHO, 1996), U.S. Surgeon General (USPHS, 1999), and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDoHaH, 2000) have emphasized the need to better identify individuals at risk for suicide. Accurate assessment of risk helps to determine treatment priorities and ensure that appropriate safety measures are put in place (Joiner, Walker, Rudd, & Jobes, 1999). Because individuals with mental disorders are more likely to attempt and complete suicide (Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999), suicide risk assessments are standard practice in treatment settings (Bryan & Rudd, 2005).

The hopelessness theory of suicide is a cognitive theory suggesting that hopelessness is an important cognitive vulnerability associated with the risk for suicide (Abramson, Alloy, Hogan, et al., 2000; Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). Specifically, hopelessness is thought to reflect a cognitive style consisting of negative attributions about the future and about one’s helplessness to improve prospects for the future. In support of this perspective, several studies in non-psychotic populations suggest that assessment of hopelessness can help identify those at increased risk for suicide. Kuo, Gallo, and Eaton (2004) examined a large community sample and found that hopelessness predicted suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, and completed suicide over a 13-year follow-up interval. Similar findings have been reported for clinical populations. Forman and colleagues (Forman, Berk, Henriques et al., 2004) found in a cross-sectional study that elevated hopelessness distinguished multiple suicide attempters from those who had made just one suicide attempt. Additionally, hopelessness was a reliable predictor of completed suicide among psychiatric patients followed for 10 and 20 years (Beck, Brown, & Steer, 1989; Brown, Beck, Steer, & Grisham, 2000).

The aforementioned studies yielded valuable findings that transformed our understanding of suicide risk. Indeed, hopelessness is consistently highlighted in guidelines for conducting suicide risk assessments (Bryan & Rudd, 2005; Joiner, Walker, Rudd & Jobes, 1999). However, it is notable that the seminal studies on hopelessness and suicide were not able to evaluate this relationship in psychotic disorders, as they focused on other populations. Importantly, suicide prevention is a critical consideration in treatment of psychosis. Rates of attempted and completed suicide are high in psychotic disorders (Addington, Williams, Young, & Addington, 2004; Caldwell & Gottesman, 1990; Clarke, Whitty, Browne et al., 2006; Palmer, Pankratz, & Bostwick, 2005; Radomsky et al., 1999; Schaffer et al., 2008), and patients with psychosis have a higher risk for suicide than other patient groups (Westermeyer, Harrow, & Marengo, 1991). It is therefore essential to evaluate the relationship between hopelessness and suicide in psychosis using the same type of long-term, prospective research that helped establish the importance of hopelessness for suicide in non-psychotic populations.

In addition, there is reason to question whether hopelessness confers suicide risk in psychosis to the same degree as in non-psychotic disorders. Psychotic disorders are associated with a wide variety of cognitive deficits (Mohamed, Paulsen, O’Leary, Arndt, & Andreasen, 1999), which could potentially alter the relevance of cognitive vulnerabilities such as hopelessness. Unfortunately, little empirical research has addressed the relationship of hopelessness to suicide in psychosis. Cross-sectional investigations suggest that hopelessness in psychotic patients is associated with increased reports of suicidality (Borgeois, Swendsen, Young et al., 2004; Kim, Jayathilake, & Meltzer, 2002). However, only two studies to date have examined the prospective relationship between hopelessness and suicide in psychosis. The first, a one-year study, found that hopelessness measured at baseline predicted attempted suicide during the subsequent year in a sample of patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Nordentoft, Jeppesen, & Abel et al., 2002). However, hopelessness no longer predicted attempted suicide when controlling for previous suicide attempts and other psychosocial variables.

The second prospective study examined predictors of attempted suicide in psychosis over seven years (Robinson, Harris, Harrigan, et al., 2010), and found that various patient characteristics, including hopelessness, are reliable predictors of subsequent attempted suicide, even when controlling for previous history of self-harm. Although this study yielded valuable information about predictors of attempted suicide in psychotic disorders, findings regarding hopelessness are difficult to interpret due to measurement issues. Hopelessness was assessed via the Royal Park Multidiagnostic Instrument for Psychosis (RPMIP). The RPMIP provides comprehensive diagnostic coverage with established reliability and validity, but for hopelessness it only yields a categorical present-absent score, and there are no published accounts of this item’s reliability or validity. Moreover, Robinson et al. only assessed hopelessness at baseline, which precluded examination of the trajectory of hopelessness in psychosis and its utility for predicting attempted suicide at different follow-up intervals. Given the measurement limitations of Robinson et al, and the equivocal findings and limited follow-up period in Nordentoft et al., the importance of hopelessness as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in patients with psychosis remains unclear.

The present study utilizes a 10-year longitudinal design and a large epidemiologic sample to clarify the relationship of hopelessness to attempted suicide in psychotic disorders. Previous work on the sample examined antecedents and associated characteristics of attempted suicide during the first four years of the study (Bakst, Rabinowitz, & Bromet, 2009; Cohen et al., 1994). The present investigation reports data from 414 patients with first-admission psychosis who were followed for 10 years. Both hopelessness and attempted suicide were assessed at multiple time-points, and hopelessness was examined as a prospective predictor of suicide attempts.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were first-admissions to one of 12 inpatient facilities in Suffolk County, Long Island between 1989 and 1995. A full description of participant characteristics and recruitment and follow-up procedures can be found elsewhere (Bromet, Jandorf, Fennig et al., 1996; Bromet, Naz, Fochtmann, Carlson, & Tanenberg-Karant, 2005; Bromet, Schwartz, Fennig et al., 1992; Mojtabai, Herman, Susser et al., 2005). Briefly, inclusion criteria were ages 15–60 years, residence in Suffolk County, clinical evidence of psychosis; exclusion criteria were a first psychiatric hospitalization more than six months before the baseline admission, moderate or severe mental retardation, and an inability to speak English. Longitudinal research consensus DSM-IV diagnoses were assigned at the 24-month point based on three administrations of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-III-R; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1992) at baseline, six months, and 24-months, as well as medical records and other relevant information from respondents, clinicians, and significant others (Schwartz, Fennig, Tanenberg-Karant et al. 2000).

Of the 675 participants admitted to the study (response rate = 72%), 628 were confirmed to meet eligibility criteria at the 24-month follow-up, and of these 42 died during the 10-year follow-up. Among the remaining 586 participants, 470 were successfully contacted at the 10-year point. This report focuses on 414 participants (70.6% of the 586) with complete information on suicide behavior at the 10-year mark. At baseline, the 414 participants with complete information reported slightly more hopelessness than the 214 with incomplete information [Cohen’s d=.2, p<.01], and were similar with regard to history of attempted suicide [X2(1)=0.04, p=.95]. In addition, t and chi-square tests revealed no differences in age, gender, ethnicity, or diagnosis between these groups (ps>.05).

Of the 414 participants, 37.4% were diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizophreniform, or schizoaffective disorder, 27.2% with bipolar disorder with psychotic features, 17.7% with major depression with psychotic features, 7.3% with drug-induced psychosis, and 10.4% with other psychoses. The sample was 57.0% male and 73.9% Caucasian with a mean age of 29.1 (SD=9.6) at baseline. Suicide data were available for 344 participants at 6-month follow-up, 323 at 24-month follow-up, 292 at 48-month follow-up, and all 414 at baseline and 10-year follow-up.

Measures

Beck Hoplessness Scale

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974) is a 20-item true-false self-report questionnaire designed to assess negative attitudes about the future. Scores range from 0 to 20. The Beck Hopelessness Scale was administered at baseline (α=.88), 6-months (α=.90), 24-months (α=.89), and 48-months (α=.91) because the original study was designed in part to predict suicide behaviors in the cohort.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-III-R) and DSM-IV. The SCID-III-R is a reliable and valid structured interview designed to diagnosis DSM Axis I disorders. The SCID was augmented with questions assessing history and severity of suicidal behavior (see Cohen et al., 1994). Data on suicidal behavior were collected at each follow-up assessment – 6-months, 24-months, 48-months, and 10-years – to assess suicidal behavior during the previous interval (i.e., whether suicide was attempted since the previous assessment).

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1960) was administered at baseline and used as a covariate to determine of the relationship between hopelessness and attempted suicide would remain significant after controlling for depression.

Statistical analyses

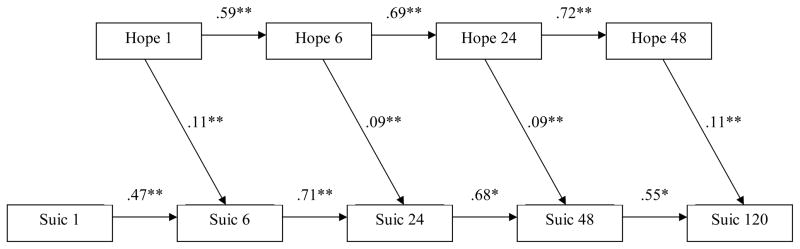

Descriptive statistics were used to assess rates of attempted suicide and mean levels of hopelessness at different time-points. Correlational analyses (Pearson and point-biserial as appropriate) and logistic regression were used to examine associations between hopelessness and attempted suicide assessed at different time points. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test whether hopelessness predicted suicide attempts above and beyond the effects of past suicidal behavior. The analysis included four hopelessness variables (baseline, 6-months, 24-months, and 48-months) and five suicide attempt variables (prior to baseline, baseline to 6-months, 6 to 24 months, 24 to 48 months, and 48 months to 10 years). Suicide attempts in the follow-up were predicted jointly by hopelessness and suicide attempts from the preceding wave (Figure 1). Follow-up hopelessness was predicted by hopelessness at the preceding assessment. We constrained paths from hopelessness to suicide attempts to be equal because they were statistically equivalent. The change in chi-square from the unconstrained to the constrained model was non-significant (X2(3)=4.58, p=.21), which confirmed that these paths were not significantly different from each other (i.e., equivalent). The SEM analysis was performed using Mplus version 5.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2004). In evaluating the model, we considered two fit indices, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Although there are no strict criteria for evaluating these fit indices, conventional rule-of-thumb guidelines suggest that CFI values of .90 or greater indicate an adequate fit, and values of .95 or greater indicate an excellent fit. Likewise, RMSEA values of .10 or less indicate an adequate fit, and values of .06 or less indicate an excellent fit (Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004). Missing data were managed with full information maximum likelihood method, and hence all available observations were used in estimation of the SEM model.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model examining relationships between hopelessness and suicide attempts assessed at multiple time-points over 10 years.

* indicates p<.05, ** indicates p<.01; All estimates are standardized.

Hope 1 indicates hopelessness at baseline; Hope 6 indicates hopelessness at 6-month follow-up; Hope 24 indicates hopelessness at 24-month follow-up; Hope 48 indicates hopelessness at 48-month followup.

Suic 1 indicates attempted suicide before baseline; Suic 6 indicates attempted suicide between baseline and 6-month follow-up; Suic 24 indicates attempted suicide between 6-month and 24-month follow-ups; Suic 48 indicates attempted suicide between 24-month and 48-month follow-ups; Suic 120 indicates attempted suicide between 48-month and 10-year follow-ups.

Results

Suicidal Behavior

Approximately 29% of participants reported a history of attempted suicide at baseline. Chi-square analyses indicated that at baseline there were statistically reliable differences in lifetime rates of attempted suicide for different diagnostic groups: drug-induced psychosis (46.7%), major depression with psychotic features (42.5%), other psychosis (27.9%), schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder (26.0%), and bipolar disorder with psychotic features (17.9%), [X2(4)=18.6, p=.001]. Just under one-fifth of the sample (18.8%) made one or more attempts during the 10 years following baseline, with a trend towards significant differences among the groups: major depression (28.3%), schizophrenia/schizoaffective (22.6%), drug-induced psychosis (20.0%), bipolar (10.4%), and other psychosis (5.6%),[X2(4)=8.4, p=.07]. Neither gender [X2(1)=0.0, p=.95] nor age [rpb =−.06, p=.36] was significantly associated with suicide attempts during the subsequent 10 years.

Four men and two women completed suicide during the 10-year follow-up (three by 4 years; three between 4–10 years). Four were diagnosed with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, and two with major depression.

Hopelessness

A repeated-measures analysis of variance indicated that scores on the Beck Hopelessness Scale were slightly higher at 6-month follow-up (M=4.7, SD=4.5) than at baseline (M=4.2, SD=4.3), 24-months (M=4.1, SD=4.3), or 48-months (M=4.0, SD=4.5), [F(3,807)=2.3, p=.08]. There was a significant main effect of diagnosis [F(4,265)=5.74, p<.001]. Specifically, post-hoc Scheffe tests indicated that the bipolar group (M=2.8, SM=0.4) had lower hopelessness scores, and the major depression group higher hopelessness scores (M=5.4, SM=0.5), compared to the schizophrenia/schizoaffective (M=4.7, SM=0.3), drug-induced psychosis (M=4.4, SM=0.8), and other psychosis (M=4.4, SM=0.6) groups. There was no statistical interaction between time and diagnosis in terms of hopelessness scores (p=.40). There was no main effect of gender on hopelessness [F(1,268)=0.89, p=.35], nor was there a relationship between age and hopelessness (correlation between age and total hopelessness was r=.04, p=.54).

In general, the correlations among the hopelessness scores assessed at different time points showed moderate temporal stability but decreased as the intervals between two time-points increased (Table 1). Specifically, the correlations ranged from a high of 0.66 (6-months with 24-months) to a low of 0.34 (baseline with 48-months). Test-retest consistency coefficients were similar for men (median r=0.49) and women (median r=0.53), and for those who did (median r=.51) and did not (median r=0.49) attempt suicide during the 10-year follow-up. Test-retest coefficients were also similar for each diagnostic group (analyses available upon request). We note that for the six patients who completed suicide, hopelessness at baseline ranged from 0 to 11, with a median of 4.

Table 1.

Correlations among hopelessness scores at different time-points

| 0 months (baseline) | 6 months | 24 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r (n) | r (n) | r (n) | |

| 0 months (baseline) | - | - | - |

| 6 months | .53 (335) | - | - |

| 24 months | .41 (325) | .61 (307) | - |

| 48 months | .34 (329) | .51 (307) | .66 (305) |

Note. All correlations are statistically significant at an alpha level of .001.

Hopelessness and Attempted Suicide

Point-biserial correlational analysis indicated that hopelessness at baseline reliably predicted attempted suicide during the subsequent 10 years (rpb =.21, p=.002). Logistic regressions indicated that this relationship did not vary by gender (p=.13) or by diagnosis (p=.55), and that the relationship remained significant when controlling for depression as measured by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (p=.01). As presented in Table 2, a closer examination of the data indicated that hopelessness best predicted attempted suicide over shorter follow-up intervals. For example, hopelessness at baseline and 6-months each significantly predicted occurrence of a suicide attempt between 24 and 48 months (rpb ranged from .16 to .22), but not between 48 months and 10 years (rpb ranged from .01 to .09). Similarly, hopelessness assessed at 24-months reliably predicted occurrence of a suicide attempt during the subsequent two years (rpb =.22) but was a poor predictor of attempted suicide between 48-months and 10 years post-baseline (rpb =.01). A series of logistic regression analyses indicated that the relationships of hopelessness to attempted suicide at different time-points did not vary by diagnosis (details available from first author upon request).

Table 2.

Hopelessness as a prospective predictor of attempted suicide in patients with 1st-admission psychotic disorders

| Hopelessness | Attempted Suicide | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 months | 6–24 months | 24–48 months | 48–120 months | |

| rpb (n) | rpb (n) | rpb (n) | rpb (n) | |

| 0 months (baseline) | .12* (327) | .09 (311) | .20** (278) | .09# (393) |

| 6 months | - | −.02 (296) | .16** (261) | .07 (350) |

| 24 months | - | - | .22** (259) | .01 (339) |

| 48 months | - | - | - | .14** (344) |

Note.

rpb = point-biserial correlation;

indicates p≤.10;

indicates p≤.05;

indicates p≤.01

Next we evaluated the incremental validity of hopelessness in predicting suicide attempts above and beyond past suicidal behavior. To address this question, we constructed a structural equation model in which suicide attempts were jointly predicted by hopelessness and suicide attempts from the preceding wave (Figure 1). This model fit the data very well with the CFI of .97 and the RMSEA of .04, both in the excellent range. The chi-square test was non-significant [X2(16)=25.6, p=.06)], which indicated lack of discrepancy between the model and the data. As expected, past suicidal behavior emerged as a powerful predictor, with standardized path coefficients ranging between .47 and .71. Moreover, hopelessness also made significant incremental contributions to the prediction of suicidality, which were significant over the entire follow-up (path coefficients ranged .09 to .12).

Finally, we examined cut-points at which baseline hopelessness offered optimum sensitivity and specificity. In general, very low cut-points were required to achieve high sensitivity, whereas specificity was high using cut-points of ≥5 and above. Specifically, a cut-point of ≥3 yielded a sensitivity of .73 and specificity of .44. A cut-point of ≥4 yielded a sensitivity of .68 and specificity of .57. A cut-point of ≥5 yielded a sensitivity of .58 and specificity of .70. A cut-point of ≥6 yielded a sensitivity of .44 and specificity of .76. Finally, we examined a cut-point of ≥9 since this is the recommended cut-point on the Beck Hopelessness Scale for identifying high suicide risk in non-psychotic populations (McMillan, Gilbody, Beresford, & Neilly, 2007). This cut-point yielded a sensitivity of .36 and specificity of .88.

Discussion

The present study used a prospective design to examine hopelessness as a predictor of attempted suicide in patients with first-admission psychotic disorders. Several features of the study design – including the 10-year follow-up period, repeated measurements of both hopelessness and attempted suicide, use of reliable and valid measures of hopelessness and clinical characteristics, and the epidemiologic nature of the sample – help provide the most definitive data to date regarding the importance of hopelessness as a risk-factor for suicide in psychosis. Approximately 30% of participants had attempted suicide prior to enrollment in the study, and just under 20% attempted suicide during the 10-year follow-up period, including six who completed suicide. These findings are consistent with previous studies noting high rates of attempted suicide in psychotic disorders (Addington et al., 2004; Caldwell & Gottesman, 1990; Clarke, Whitty, Browne et al., 2006; Palmer et al., 2005; Radomsky, Haas, Mann, & Sweeney, 1999; Westermeyer, Harrow, & Marengo, 1991).

The primary study aim was to examine hopelessness as a prospective predictor of suicidal behavior. Results indicated that hopelessness reliably predicted the occurrence of attempted suicide during a 10-year follow-up period. Hopelessness appeared most useful for predicting the occurrence of attempted suicide within four years of a hopelessness assessment. For example, hopelessness at baseline, 6-months, and 24-months each predicted the occurrence of a suicide attempt between the 24- and 48-month assessments, but not between the 48-month and 10-year assessments. This pattern of results may be due in part to the moderate temporal stability of hopelessness scores. Test-retest correlations ranged from .34 to .66, and in general were smaller for larger test-retest intervals. Since hopelessness at one time point is only a modest predictor of hopelessness several years later, it follows that the ability of hopelessness to predict subsequent suicidal behavior would decrease as time between the hopelessness assessment and interval of interest increases.

Notably, structural equation modeling indicated that prospective associations between hopelessness and attempted suicide remained statistically significant when controlling for past suicidal behavior. This finding suggests that assessing hopelessness provides information about suicide risk in psychosis over and above past suicidal behavior. The modest correlations between hopelessness and subsequent suicidal behavior in the present study were similar in magnitude to correlations reported in other studies. For example, the difference in hopelessness between suicide completers and non-completers reported by Beck et al. (1989) corresponds to a correlation of approximately r=.2. Modest but reliable relationships between hopelessness and subsequent attempted suicide have also been reported in community (Kuo et al., 2004) and psychotic (Nordentoft et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2009) populations.

Importantly, our findings suggest that the optimal cut-point on the Beck Hopelessness Scale for predicting suicide attempts is lower in psychotic than non-psychotic populations. Guidelines for the Beck scale suggest an optimal cut-point of ‘greater than or equal to 9’ (Mcmillan et al., 2007). In a meta-analysis, McMillan et al. (2007) found that this cut-point yielded sensitivity of .78 and specificity .42 for predicting non-fatal self-harm. However, in our epidemiological sample of individuals with first-episode psychosis, a cut-point of ‘greater or equal to 3’ yielded comparable sensitivity (.73) and specificity (.44).

The results have implications for clinical assessment and intervention. Findings suggest that assessment of hopelessness could help increase the accuracy of suicide risk assessments for psychotic patients, and that even moderate levels of hopelessness indicate heightened suicide risk among individuals with psychosis. Moreover, findings suggest that hopelessness assessments convey reliable information about suicide risk several years post-assessment. Predictive utility appears highest within four- to six-years post-assessment.

Finally, results have implications for theoretical models of suicide. Some view hopelessness as an important factor in the etiology of suicidal ideation and behavior, but these theories are most often applied to non-psychotic depression (Abramson, Alloy, Hogan, et al., 2000; Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). Results from the current study suggest that hopelessness has similar relevance for patients with psychotic disorders.

We note several study limitations. This study examined attempted suicide as a dichotomous variable. Future studies should examine hopelessness in relation to particular characteristics of attempted suicide such as frequency, lethal intent, and medical severity. In addition, this study was not able to examine hopelessness as a predictor of death by suicide because this outcome was too rare for reliable statistical analysis. Finally, it is important to note that this study focused on hopelessness but not other variables with important theoretical and empirical relationships to attempted suicide such as “psychache” (Shneidman, 1993) or burdensomeness, belongingness, and fearlessness of death (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Results suggest that hopelessness is one useful predictor of attempted suicide, but future research will be important for clarifying the role of hopelessness in the context of elaborated models of suicide risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH44801 (E.J. Bromet) and a grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (E.D. Klonsky). We thank Dr. Charles Rich for assistance in the design of this study. We are indebted to the project psychiatrists, interviewers, data team and mental health professionals in Suffolk County for their outstanding support.

Footnotes

We are particularly indebted to the study participants for contributing their time and valuable input throughout the course of the study.

Contributor Information

E. David Klonsky, University of British Columbia.

Roman Kotov, Stony Brook University.

Shelly Bakst, Bar Ilan University.

Jonathan Rabinowitz, Bar Ilan University.

Evelyn J. Bromet, Stony Brook University

References

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Gibb BE, Hanklin BL, et al. The hopelessness theory of suicidality. In: Jointer TE, Rudd MD, editors. Suicide Science: Expanding the Boundaries. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Williams J, Young J, Addington D. Suicidal behaviour in early psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:116–120. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakst S, Rabinowitz J, Bromet EJ. Antecedents and patterns of suicide behaviors in first-admission psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;36:880–889. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA. Prediction of eventual suicide in psychiatric inpatients by clinical ratings of hopelessness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:309–310. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois M, Swendsen J, Young F, Amador X, Pini S, Cassano GB, et al. Awareness of disorder and suicide risk in the treatment of schizophrenia: Results of the international suicide prevention trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1494–1496. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fennig S, Lavelle J, Kovasznay B, Ram R, Tanenberg-Karant M, Craig T. The Suffolk County Mental Health Project: Demographic, pre-morbid, and clinical correlates of 6-month outcome. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:953–962. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Naz B, Fochtmann LJ, Carlson GA, Tanenberg-Karant M. Long-term diagnostic stability and outcome in recent first-episode cohort studies of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31:639–642. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Geller L, Jandorf L, Kovasznay B, Lavelle J, Miller A, Pato C, Ranganathan R, Rich C. The epidemiology of psychosis: The Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1992;18:243–255. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients. A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Advances in assessment of suicide risk. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;62:185–200. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. Schizophrenics kill themselves too: A review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16:571–589. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M, Whitty P, Browne S, Mc Tigue O, Kinsella A, Waddington JL, et al. Suicidality in first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;86:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Lavelle J, Rich CL, Bromet E. Rates and correlates of suicide attempts in first-admission psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;90:167–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Berk MS, Henriques GR, Brown GK, Beck AT. History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker for severe psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:437–443. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why People Die By Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH, Gallo JJ, Eaton WW. Hopelessness, depression, substance disorder, and suicidality: A 13-year community-based study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39:497–501. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0775-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Walker RL, Rudd MD, Jobes DA. Scientizing and routinizing the assessment of suicidality in outpatient practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1999;30:447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Jayathilake K, Meltzer HY. Hopelessness, neurocognitive function, and insight in schizophrenia: Relation to suicidal behavior. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;60:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau K-T, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan D, Gilbody S, Beresford E, Neilly L. Can we predict suicide and non-fatal self-harm with the Beck Hopelessness Scale? A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:769–778. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed S, Paulsen JS, O’Leary D, et al. Generalized cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a study of first-episode patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:749–754. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.8.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Herman D, Susser ES, Sohler N, Craig TJ, Lavelle J, Bromet EJ. Service use and outcomes of first-admissions patients with psychotic disorders in the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1291–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M, Kassow P, Petersen L, Thorup A, et al. OPUS Study: Suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation, and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis: One-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;181 (suppl 43):s98–s106. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:247–253. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radomsky ED, Haas GL, Mann JJ, Sweeney JA. Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1590–1595. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Harris MG, Harrigan SM, Henry LP, Farrelly S, Prosser A, et al. Suicide attempt in first-episode psychosis: A 7.4 year follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;116:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer A, Flint AJ, Smith E, Rothschild AJ, Mulsant BH, Szanto K, et al. Correlates of suicidality among patients with psychotic depression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:403–414. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Tannenberg-Karant M, Carlson G, Craig T, Galambos N, Lavelle J, Bromet E. Congruence of diagnosis two years after a first-admission diagnosis of psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:593–600. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shneidman ES. Suicide as psychache. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1993;181:145–147. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USPHS. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent suicide. Washington, DC: United States Public Health Service; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- USDoHaH. Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Healthy People 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer JF, Harrow M, Marengo JT. Risk for suicide in schizophrenia and other psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1991;179:259–266. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Prevention of suicide: guidelines for the formulation and implementation of national strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]