Abstract

Objective

A multi-pronged approach to improve vital organ perfusion during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) that includes sodium nitroprusside (SNP), active compression-decompression (ACD)-CPR, an impedance threshold device, and abdominal pressure (SNPeCPR) has been recently shown to increase coronary and cerebral perfusion pressures and higher rates of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) versus standard CPR. To further reduce reperfusion injury during SNPeCPR we investigated the addition of adenosine and four 20-second controlled pauses (CP) spread throughout the first 3 minutes of SNPeCPR. The primary study endpoint was 24-hour survival with favorable neurological function after 15 minutes of untreated ventricular fibrillation. (VF)

Design

Randomized, prospective blinded animal investigation.

Setting

Preclinical animal laboratory.

Subjects

32 female pigs (4 groups of 8) 32±2Kg.

Interventions

After 15 minutes of untreated VF isoflurane anesthetized pigs received 5 minutes of either standard CPR, SNPeCPR, SNPeCPR+adenosine or CP-SNPeCPR+adenosine. After 4 minutes of CPR all animals received epinephrine (0.5 mg) and a defibrillation shock one minute later. SNPeCPR-treated animals received SNP (2 mg) after 1 minute of CPR and 1 mg after 3 minutes of CPR. After 1 minutes of SNPeCPR, adenosine (24 mg) was administered in two groups.

Measurements and Main Results

A veterinarian blinded to the treatment assigned a cerebral performance category score of 1–5 (normal, slightly disabled, severely disabled but conscious, vegetative state, dead, respectively) 24 hours after ROSC. SNPeCPR, SNPeCPR+adenosine, CP-SNPeCPR+adenosine resulted in significantly higher 24-hour survival rate compared to standard CPR (7/8, 8/8, 8/8 versus 2/8, respectively p<0.05). The mean CPC scores for standard CPR, SNPeCPR, SNPeCPR+adenosine or CP-SNPeCPR+adenosine were 4.6 ±0.7, 3±1.3, 2.5±0.9 and 1.5±0.9 (p<0.01 for CP-SNPeCPR+adenosine compared to all other groups).

Conclusions

Reducing reperfusion injury and maximizing circulation during CPR significantly improved functional neurological recovery after 15 minutes of untreated VF. These results suggest that brain resuscitation after prolonged cardiac arrest is possible with novel non-invasive approaches focused on reversing the mechanisms of tissue injury.

Keywords: sodium nitroprusside, adenosine, reperfusion injury, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, survival, neurological function, left ventricular function, active compression decompression CPR, impedance threshold device

INTRODUCTION

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) rates have remained poor over the past half-century with only minimal if any improvements in neurologically intact survival (1). Clinical studies have historically demonstrated that when ventricular fibrillation (VF) is untreated for more than 10 minutes short and long term survival is severely reduced (2). In animal models, current non-invasive methods of resuscitating untreated ventricular fibrillation of durations longer than 12–13 minutes prohibit short and long-term neurological recovery (3–5). Successful resuscitation after 12–15 minutes of untreated VF has been used as the model to evaluate post resuscitation left ventricular dysfunction, which manifests as global hypokinesis and moderate decreases in left ventricular ejection fraction that are obvious within the first hour and continue to decline up to four hours post resuscitation (6).

Sodium nitroprusside “enhanced”-cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or SNPeCPR, is a method of resuscitation that consists of: 1) active compression-decompression CPR with an impedance threshold device (ACD-CPR + ITD) which improves vital organ blood flow, and improves short and long term survival compared to standard CPR in both animal and human studies (7–9), 2) manual lower abdominal binding which mechanically increases resistance to descending aortic blood flow, augments venous blood return to the heart, thereby effectively redistributing blood flow (10, 11) and, 3) high dose intravenous boluses of sodium nitroprusside which vasodilates coronary and cerebral vascular beds and decreases peripheral vascular resistance to the heart and brain (12, 13).

Recent animal studies have demonstrated that SNPeCPR can maintain heart and brain viability and significantly improve carotid blood flow, end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2), and ROSC and 24-hour survival rates with favorable neurological function compared to S-CPR after 8 minutes of untreated VF and with up to 25 minutes of CPR (12). Furthermore, SNPeCPR use has resulted in a >90% ROSC rate after 15 minutes of untreated ventricular fibrillation and pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest (13). SNPeCPR significantly improved outcomes in the same animal model when compared to the 2010 American Heart Association resuscitation recommendations (standard CPR) ACLS protocol (13).

Recognizing that heart and brain recovery after a prolonged ischemic insult may depend upon physiological processes independent of coronary and cerebral perfusion, in the current investigation we focused on novel ways to protect the heart and brain from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Building upon our recent studies with SNPeCPR and recent finding by others in models of regional myocardial and cerebral ischemia (12–16), in this study we tested two new strategies aimed at improving neurological and myocardial function after prolonged cardiac arrest. Those strategies include: 1) addition of a large bolus of adenosine in addition to the SNP bolus at the initiation of CPR; adenosine has been shown to have cardiac protective effects after ischemia both in animals and humans (17–20) and 2) controlled introduction of blood flow with a “stuttering” manner by providing intermittent 20-second pauses in chest compressions and ventilations (Controlled Pauses: CP−) throughout the first 3 minutes of reperfusion. “Stuttering” re-introduction of blood flow has been shown to protect the myocardium and the brain from ischemia reperfusion injury in clinical scenarios of regional ischemia during ST elevation myocardial infarction and stroke both in animals and humans (21–24).

We hypothesized that the combination of the above strategies will provide cerebral and myocardial protection against reperfusion injury and facilitate functional recovery. The purpose of this study, then, was to evaluate hemodynamics, acid-base status, rates of ROSC and 24-hour survival as well as left ventricular function and 24-hour neurological recovery in pigs with 15 minutes of untreated ventricular fibrillation (VF) resuscitated with different multi-pronged reperfusion injury protection strategies (SNPeCPR + adenosine; CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine) versus SNPeCPR alone and standard CPR.

MATERIALS and METHODS

All studies were performed by a qualified, experienced research team in Yorkshire female farm pigs weighing 32 ± 2 kg. A certified and licensed veterinarian provided a blinded neurological assessment at 24 hours. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation of Hennepin County Medical Center. All animal care was compliant with the National Research Council’s 1996 Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Preparatory Phase

The anesthesia, surgical preparation, data monitoring, and recording procedures used in this study have been described previously (25). Briefly, we employed aseptic surgical conditions, using initial sedation with intramuscular ketamine (7 mL of 100 mg/mL, Ketaset, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, Iowa) followed by inhaled isoflurane at a dose of 0.8 to 1.2%. Pigs were intubated with a size 7.0 endotracheal tube. The animal’s bladder temperature was maintained at 37.5 ± 0.5°C, with a warming blanket (Bair Hugger, Augustine Medical, Eden Prairie, Minnesota). Central aortic blood pressure was recorded continuously with a micromanometer-tipped (Mikro-Tip Transducer, Millar Instruments, Houston, Texas) catheter placed at the beginning of the descending thoracic aorta. A second Millar catheter was inserted in the right atrium via the right external jugular vein. All animals received an intravenous heparin bolus (100 units/kg) and 500 units of heparin every hour until surgical repair was completed. An ultrasound flow probe (Transonic 420 series multichannel, Transonic Systems, Ithaca, New York) was placed to the right internal carotid artery to record blood flow (ml/min). The animals were then ventilated with room air, using a volume-control ventilator (Narcomed, Telford, Pennsylvania), with a tidal volume of 10 mL/kg and a respiratory rate adjusted to continually maintain a PaCO2 of 40 mmHg and PaO2 of 80 mmHg (blood oxygen saturation >95%), as measured from arterial blood (Gem 3000, Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, Massachusetts) to adjust the ventilator as needed. Surface electrocardiographic tracings were continuously recorded. All data were recorded with a digital recording system (BIOPAC MP 150, BIOPAC Systems, Inc., CA, USA). End tidal CO2 (ETCO2), tidal volume, minute ventilation, and blood oxygen saturation were continuously measured with a respiratory monitor (CO2SMO Plus, Novametrix Medical Systems, Wallingford, Connecticut).

Measurements and Recording

Thoracic aortic pressure, right atrial pressure, ETCO2, and carotid blood flow were continuously recorded. Coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) during CPR was calculated from the mean arithmetic difference between right-atrial pressure and aortic pressure during the decompression phase. Carotid artery blood flow was reported in ml/sec.

Experimental Protocol

After the surgical preparation was complete, oxygen saturation on room air was greater than 95%, and ETCO2 was stable between 35–42 mm Hg for five minutes, ventricular fibrillation was induced by delivering direct intracardiac current via a temporary pacing wire (St Jude Medical, Minnetonka, Minnesota). The ventilator was disconnected from the endotracheal tube. Standard and active compression decompressions CPR were performed with a pneumatically driven automatic piston device (Pneumatic Compression Controller, Ambu International, Glostrup, Denmark) as previously described (26). During S-CPR, uninterrupted chest compressions were performed at a rate of 100 compressions/min, with a 50% duty cycle and a compression depth of 25% of the anterior-posterior chest diameter were provided. With ACD-CPR, the chest was actively pulled upwards after each compression with a decompression force of 60 lbs. Simultaneous with ACD-CPR an impedance threshold device (ResQPOD TM, Advanced Circulatory Systems, Inc, Roseville, MN) with a resistance of −7mmHg was attached to the endotracheal tube. In addition, during SNPeCPR, manual abdominal binding was performed to provide approximately 40 lbs of force as previously described (27, 28). During both standard and ACD- CPR, asynchronous positive-pressure ventilations were delivered with room air (FiO2 of 0.21) with a manual resuscitator bag. The tidal volume was maintained at ~10ml/kg and the respiratory rate was 10 breaths/min. The investigators were blinded to hemodynamics during CPR.

Protocol

Following 15 minutes of untreated VF, 32 pigs were randomized to either 5 minutes of 1) Standard CPR, 2) SNPeCPR, 3) SNPeCPR + adenosine, or 4) CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine (four groups of 8 animals) before the first defibrillation attempt. Epinephrine was administered in all groups in 0.5 mg (~15mcg/kg) bolus at minute four whereas SNP was delivered into the jugular vein in the SNPeCPR, SNPeCPR + adenosine, and CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine groups as a 2 mg bolus at minute one and a second 1 mg bolus at minute three of CPR. In the last two groups, adenosine was administered as a single 24 mg intravenous bolus after the first SNP bolus.

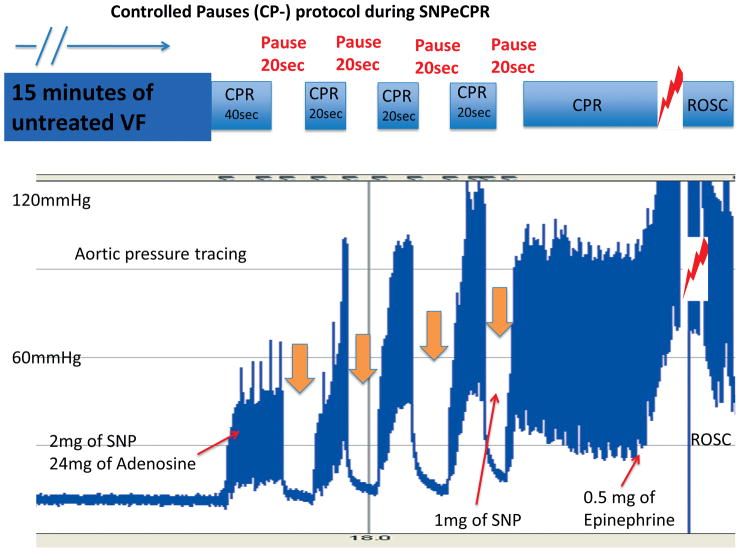

The 8 animals randomized to receive controlled pauses (CP) had 40 seconds of SNPeCPR and then received 2 mg of SNP and 24 mg of adenosine. This was followed by 4 cycles of a 20-second pause and 20 seconds of SNPeCPR, until the end of the 3rd minute of CPR. Then animals received uninterrupted SNPeCPR until defibrillation (Figure 1). A bolus of 24 mg of adenosine (compared to 12 mg) was chosen because in our preliminary studies it significantly increased carotid blood flow during CPR and the effect was longer lasting, extending into the post resuscitation period.

Figure 1. Controlled-pauses protocol during SNPeCPR.

In the CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine group during the first 3 minutes of SNPeCPR, animals received four 20-second pauses and each pause was followed by 20 seconds of SNPeCPR. That “stuttering” introduction of reperfusion is called “Controlled Pauses”.

SNPeCPR: sodium nitroprusside “enhanced”-CPR; VF: ventricular fibrillation; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation; SNP: sodium nitroprusside.

Resuscitation efforts were continued until ROSC was achieved or a total of 15 minutes of CPR had occurred. Defibrillation was delivered with 150-Joule biphasic shocks after five minutes of CPR. If ROSC was not achieved, defibrillation was delivered every 2 minutes thereafter during CPR.

Post ROSC care

After ROSC was achieved, animals were connected to the mechanical ventilator. Supplemental oxygen was added only if arterial saturation was lower than 90%. Animals were observed under general anesthesia with isoflurane until hemodynamically stable. Hemodynamic stability was defined as a mean aortic pressure > 55mmHg without pharmacological support for 10 minutes and normalization of ETCO2 and acidosis. Animals that had a stable post-ROSC rhythm but were hypotensive (mean arterial pressure <50mmHg) received 1000 ml of IV normal saline bolus over 60 minutes. If mean arterial pressure was still <50mmHg, they received increments of 0.1–0.2mg intravenous epinephrine every 5 minutes until MAP rose above 50mmHg. If pH was lower than 7.2, 50–100 mEq of NaHCO3 were given intravenously. That was repeated as needed for significant acidosis. At that point vascular repair of the internal jugular and the left common femoral artery were then performed. Arterial blood gases were obtained at baseline, at 5 min CPR, and every 30 minutes following ROSC.

Survivors were given intramuscular analgesic injections of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication as previously described and had free access to water and food (28). There was no other post-ROSC medical care provided after the vascular repair. Animals were returned to their runs and were observed every two hours for the first six hours for signs of distress or accelerated deterioration of their function. If animals met predetermined criteria or if the veterinarian judged that they were in severe distress they were euthanized per IACUC protocol.

Neurological assessment

Twenty-four hours after ROSC, a certified veterinarian, blinded to the intervention, assessed the pigs’ neurological function based upon a cerebral performance category (CPC) scoring system modified for pigs. The veterinarian used clinical signs such as response to opening the cage door, response to noxious stimuli if unresponsive, response to trying to lift the pig, whether the animal could stand, move all four limbs, walk, eat, urinate, defecate, and respond appropriately to the presence of a person walking into the cage. The following scoring system was used: 1= normal; 2 = slightly disabled; 3 =severely disabled but conscious; 4 = vegetative state; a 5 was given to animals that died in the lab due to unachievable ROSC or died in the cage following ROSC (28). A dichotomous assessment of good (CPC ≥ 2) versus poor (CPC >2) outcomes was also evaluated. Except the veterinarian, post resuscitation care was not blinded since the same team performed CPR and provided post-ROSC care.

Echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular function

A transthoracic echocardiogram was obtained on all survivors 1 and 4 hours post ROSC. Images were obtained from the right parasternal window that provides similar views as the long and short parasternal windows in humans (29). Ejection fraction was assessed using Simpson’s method of volumetric analysis by an independent clinical echocardiographer blinded to the treatments (30). Before echocardiographic evaluation, any inotropic support was stopped for at least 20 minutes and, if needed, was restarted immediately after the echocardiographic evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Baseline data, hemodynamic parameters and blood gases during and after CPR were analyzed with two-way ANOVA. Pairwise comparison of subgroups was performed with the Student-Newman-Keuls test. A 2-tailed Fischer exact test was used to compare 24-hour survival rate. A t-test was used to evaluate mean CPC scores between groups. The primary study endpoint was survival with a favorable neurological function 24 hours ROSC, as determined by a CPC score of <3. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

There were no significant baseline differences between treatment groups in any hemodynamic or respiratory parameters. (Table 1 and 2)

Table 1.

Hemodynamics, Resuscitation Rates, and Left ventricular ejection fraction.

| CPR method | Measurement | Baseline | 2 min CPR | 5 min CPR | 1 hour ROSC | 4 hour ROSC | Number of shocks to initial ROSC | Post ROSC epinephrine dose | ROSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-CPR | SBP | 82±6 | 48±3 | 76±5 | 86±7 | 78±8 | 6±2 | 2.2±1.2 | 5/8 |

| DBP | 60±3 | 18±5 | 31±4 | 57±11 | 61±9 | ||||

| RA | 3±2 | 2±1 | 2±3 | 0.5±2 | 4±2 | ||||

| CPP | 57±6 | 16±4 | 29±3 | 57±8 | 57±4 | ||||

| CBF | 186±39 | 38±15 | 18±6 | 113±26 | 137±16 | ||||

| LVEF % | 60±12 | N/A | N/A | 31±9 | 28±10 | ||||

| SNPeCPR | SBP | 87±5 | 65±3* | 110±4* | 83±8 | 76±4 | 3±4 | 0.7±0.6* | 7/8 |

| DBP | 56±7 | 28.±6* | 39±4 * | 63±6 | 29.6±4 | ||||

| RA | 3±2 | 8±4* | 6±3 | 1±3 | 4±2 | ||||

| CPP | 53±4 | 20±5* | 33±4* | 61±5 | 23.2±4 | ||||

| CBF | 176±48 | 158±25* | 86±26* | 185±34* | 163±43 | ||||

| LVEF % | 62±8 | N/A | N/A | 53±12 | 55±9 | ||||

| SNPeCPR+ Adenosine | SBP | 91±5 | 77±3* | 122±9 | 86±9 | 76±9 | 3±3 | 0.6±0.8* | 8/8 |

| DBP | 64±4 | 26±2.2* | 40±6 * | 71±7 | 62±7 | ||||

| RA | 2±2 | 6±1* | 4±4 | 1±2 | 5±3 | ||||

| CPP | 62±4 | 24±3* | 36±5* | 70±7 | 57±6 | ||||

| CBF | 181±25 | 189±55* | 135±44*¶ | 333±88*¶ | 275±62*¶ | ||||

| LVEF % | 60±13 | N/A | N/A | 72±10*¶ | 77±13¶ | ||||

| CP-SNPeCPR+ Adenosine | SBP | 87±5 | 57±7 | 156±11*¶§ | 88±11 | 86±13 | 2±1*¶§ | 0.2±0.2*¶§ | 8/8 |

| DBP | 62±4 | 28±2 | 72±4*¶§ | 72±4 | 65±7 | ||||

| RA | 3±2 | 5±2 | 6±7* | 2±2 | 3±3 | ||||

| CPP | 59±3 | 23±5 * | 66±4*¶§ | 70±3 | 62±4 | ||||

| CBF | 173±37 | 228±25*¶ | 128±47*¶ | 403±76*¶ | 193±59*¶ | ||||

| LVEF % | 58±11 | N/A | N/A | 79±7*¶ | 80±7¶ |

Values are shown as Mean ± SD. CPR was performed with either standard CPR or SNPeCPR or SNPeCPR + adenosine or CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine. All pressures in mm Hg, all flows in ml/min. SBP= systolic blood pressure, DBP= diastolic blood pressure, RA= right atrial pressure, CPP= coronary perfusion pressure, CBF= carotid blood flow, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction (%).

mean statistically significant difference compared to S-CPR, SNPeCPR and SNPeCPR + adenosine respectively.

SNPeCPR: sodium nitroprusside-enhanced CPR; S-CPR: standard CPR.

CP: controlled pauses

Table 2.

Arterial Blood Gasses during CPR and after ROSC

| CPR method | Measurement | Baseline | 5 min CPR | 30 min ROSC | 4 hour ROSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-CPR | pH | 7.39±0.04 | 7.22±0.07 | 7.23±0.04 | 7.33±0.01 |

| pCO2 | 42±3 | 38±2 | 39±1 | 33±1 | |

| pO2 | 96±5 | 76±3 | 99±5 | 85±6 | |

| HCO3 | 23±5 | 16±2 | 18±2 | 18±4 | |

| ETCO2 | 40±2 | 19±3 | 37±7 | 42±3 | |

| SNPeCPR | pH | 7.41±0.03 | 7.19±0.08 | 7.28±0.04 | 7.31±0.01 |

| pCO2 | 40±3 | 47±5 | 40±3 | 43±1 | |

| pO2 | 93±3 | 84±16 | 98±6 | 101±14 | |

| HCO3 | 24±2 | 17±0.5 | 17±2 | 18±2 | |

| ETCO2 | 39±3 | 29±5* | 36±4 | 38±5 | |

| SNPeCPR + Adenosine | pH | 7.42±0.03 | 7.15±0.06* | 7.24±0.06 | 7.29±0.01 |

| pCO2 | 38±2 | 45±4 | 43±3 | 41±4 | |

| pO2 | 91±7 | 74±8 | 91±6 | 90±8 | |

| HCO3 | 24±3 | 15±2 | 16±2 | 17±2 | |

| ETCO2 | 41±3 | 31±6* | 36±4 | 38±5 | |

| CP-SNPeCPR + Adenosine | pH | 7.41±0.04 | 7.23±0.06§ | 7.38±0.05*¶§ | 7.41±0.04*¶§ |

| pCO2 | 40±3 | 51±6 | 37±4 | 40±6 | |

| pO2 | 93±5 | 84±11 | 88±6 | 93±5 | |

| HCO3 | 24±3 | 22±4 | 20±2*¶§ | 24±2*¶ | |

| ETCO2 | 38±4 | 34±4*¶ | 42±3¶§ | 39±4 |

Mean ± SD. Arterial blood gas measurements at baseline, during CPR, and after ROSC. Partial pressures in torr. SaO2: percent oxygen saturation; HCO3: bicarbonate; ETCO2: end-tidal CO2.

mean statistically significant difference compared to standard (S−) CPR, SNPeCPR and SNPeCPR + adenosine respectively.

CPR Hemodynamics

SNPeCPR provided significantly higher internal carotid blood flow (CBF) during CPR compared to standard CPR in all animals. Addition of adenosine to SNPeCPR significantly increased carotid blood flow compared to SNPeCPR alone both during CPR and especially after ROSC. (Table 1)

Animals that received CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine had higher arterial blood pressure (156±11/72±4 mmHg) and coronary perfusion pressure (66±4 mmHg) after 5 minutes of CPR compared to all other groups. The effect of epinephrine in the animals that received CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine was pronounced and the aortic pressure and coronary perfusion pressures were increased to normal or higher than normal resting values. (Table 1)

In the animals that received CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine, carotid blood flow during the pauses was essentially zero and during CPR ranged from 128±47 to 228±25 ml/sec as seen in Table 1.

Return of Spontaneous Circulation and 24-hour Survival

There were no significant differences in ROSC between groups. (Table 1) In the standard CPR group, 5/8 animals achieved ROSC, and 2/8 animals survived 24 hours. In the SNPeCPR group, 7/8 animal had initial ROSC and survived to 24 hours (p=0.04 for 24-hour survival rate compared to standard CPR). In the SNPeCPR + adenosine and CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine groups, 8/8 and 8/8 animals had ROSC and survived to 24 hours (p= 0.007 for 24-hour survival rate compared to standard CPR for both groups, respectively) (Figure 2)

Figure 2. 24-hours neurological assessment.

SNPeCPR significantly improved neurological function compared to standard CPR. The addition of adenosine on SNPeCPR did not significantly improve neurological function further compared to SNPeCPR alone. Finally, the CP-SNPeCPR + Adenosine (four 20-sec pauses) group had 6/8 animals that were scored blinded as normal (CPC of 1) and significantly improved compared to all other groups. CPC= cerebral performance category score: (1=normal, 2=mild deficit, 3= severe deficit, 4 = coma, 5= dead) SNPeCPR: sodium nitroprusside-enhanced CPR; S-CPR: standard CPR.

CP: controlled pauses. * ¶ § mean statistically significant difference compared to standard CPR, SNPeCPR and SNPeCPR + adenosine respectively.

Animals in the SNPeCPR groups were significantly more stable hemodynamically and therefore received significantly less epinephrine than standard CPR during the recovery period. (Table 1) Three of the five animals treated with standard CPR and had ROSC were unstable and died during the night.

Left Ventricular Function

Echocardiographic evaluation at 1 hour revealed that animals receiving SNPeCPR alone had a significantly higher left ventricular ejection fraction than those animals treated with standard CPR (53±12% vs. 31±9%, p<0.001). The effect was maintained at 4 hours (55±9% vs. 28±10%, p=0.001). Addition of adenosine to SNPeCPR alone resulted in hyper-dynamic function (72±10% and 77±13% at 1 and 4 hours respectively, p < 0.001 compared with standard CPR and SNPeCPR for both time points). Left ventricular ejection fraction was also hyperdynamic and not significantly different in the animals that received CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine (79±7% and 80±7%, at 1 and 4 hours respectively) compared to animals that received SNPeCPR + adenosine. (Table 1)

Neurological Function at 24 hours

The number of pigs with good neurological function was significantly higher in the animals that received CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine compared to all other groups. (Figure 2) Two animals that received standard CPR and survived to 24 hours had CPC scores of 3 and 4 (coma) respectively. The 24-hour neurological outcome (CPC scores) did not differ significantly between the animals that received SNPeCPR and SNPeCPR + adenosine, but both groups were significantly better than S-CPR, p< 0.008 and p< 0.0001, respectively. Animals that additionally received four 20-second controlled pauses during the first 3 minutes of CPR (CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine), demonstrated significant improvement in their neurological function and 6/8 were scored with a CPC of 1 (p<0.001 compared with standard CPR, p=0.009 compared with SNPeCPR, and p=0.01 compared with SNPeCPR + adenosine). Nearly all animals had a left hind leg weakness during walking that was not scored since it was co-existent with the site of the femoral artery cut down and femoral nerve trauma. (Figure 2)

Blood Gas and End tidal CO2

There were no significant differences in blood gas values at baseline between groups. After 5 minutes of CPR there were no significant differences in blood gases except for a significantly lower arterial pH in the SNPeCPR + adenosine group. ETCO2 was significantly lower in the standard CPR group compared to all other groups after 5 minutes of CPR. Thirty minutes post ROSC the animals in the CP-SNPeCPR + adenosine group had normalized their blood gases whereas the arterial pH values in all other groups remained significantly lower. (Table 2)

DISCUSSION

In this investigation a novel strategy to reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury was combined with SNPeCPR and implemented in pigs after 15 minutes of untreated ventricular fibrillation. This new approach resulted in complete neurological recovery in 6 of 8 pigs and a substantial reduction in post resuscitation left ventricular dysfunction. To our knowledge this is the first time that survival rates with consistently favorable neurological outcomes have been reported using the combination of non-invasive techniques and pharmacological therapies after 15 minutes of untreated cardiac arrest.

This study focused on two critical physiological targets for improving resuscitation outcome. First, a new CPR technique was implemented to increase ROSC rates by enhancing circulation and perfusion. Without ROSC any other strategy to mitigate injury is futile. Second, we implemented an innovative method to minimize the injury that is inevitably caused by re-introduction of flow to ischemic tissues (16, 22).

SNPeCPR was used to augment circulation and vital organ perfusion. With this approach ROSC rates were nearly 100% in the SNPeCPR group, but favorable neurological recovery was only observed in half the animals. The addition of exogenous adenosine was chosen to minimize impairment because it has been shown to offer myocardial and cerebral protection from ischemia reperfusion injury. Multiple studies have shown that when adenosine is given during reperfusion of ST-elevation myocardial infarction it provides reperfusion injury protection, infarct size is significantly reduced and microcirculation reactivity is protected (17–20). Similar but less clear outcomes have been shown for cerebral protection in stroke from ischemia and reperfusion (31–33). Our results suggest that the addition of adenosine to SNPeCPR eliminated post resuscitation myocardial dysfunction since the ventricles were shown to be hyperdynamic in the absence of inotropic medications. Addition of adenosine alone, however, did not significantly alter neurological function in this study, although a relative contribution cannot be excluded since the study was not powered or designed to address this question.

The implementation of four controlled pauses of the chest compressions and ventilations (CP) at the start of SNPeCPR was used to decrease reperfusion injury. This new intervention consistently resulted in clinically measureable and relevant neurological recovery in the absence of prolonged intensive care or therapeutic hypothermia. Controlled pauses provide a “stuttering” introduction of blood flow: repeated 20-second pauses followed by 20 seconds of CPR were used only during the first 3 minutes after CPR initiation. While this new approach may appear to be antithetical to current thinking that continuous uninterrupted chest compressions are an essential element of modern CPR, three to four pauses of 15–20 seconds duration during the first 3 minutes after CPR initiation followed by continuous chest compressions with asynchronous ventilations for the remainder of the resuscitation appeared to positively impact neurological outcome after very prolonged global cerebral ischemia.

The supporting evidence that short duration pauses of blood flow during the first several minutes of reperfusion are beneficial for organ preservation is extensive both in the cardiology and, more recently, neurology literature. Pauses during reperfusion of acute myocardial infarction have been shown to significantly decrease infarct size (22, 23). Stutter reperfusion with 15–20 second pauses at the initiation of reperfusion of stroke has been shown to significantly decrease injury in a rat model (34). Furthermore, 15-second cycles of on/off flow in the same model with 10 minutes of global ischemic cerebral insult have provided significant cerebral preservation and recovery (34). The latter model is relevant to cardiac arrest where the ischemic insult is systemic and global. These mechanisms for protection of both the heart and brain have been well-studied and are currently considered to be mediated by mitochondrial protection (15).

In all studies where stutter flow has been shown to be beneficial and protective from regional ischemia/reperfusion injury, the duration of ischemia (absence of flow prior to reperfusion) was significantly longer than 15 minutes (16, 22). Although systemic ischemia during cardiac arrest is considered a severe and global insult, the potential for recovery of the individual organs may also be greater since the average ischemic time (no flow) in cardiac arrest (<15 minutes) is less than the ischemic time during myocardial (<4 hours) or cerebral infarction (<3 hours) where the pauses in reperfusion have shown benefit (16, 22).

This study shows that controlled, intentional cycles of CPR/pauses for the first 3 minutes was associated with significant improvements in neurological and cardiac recovery. The significant improvement observed in neurological outcomes with the introduction of mechanical reperfusion injury protection, suggests that this strategy is critical in decreasing the injury of reperfusion following untreated cardiac arrest after initiation of CPR. Generation of flow also does not appear as critical during the first 3 minutes of resuscitation, but becomes more significant later to achieve ROSC. It is important to emphasize that unintentional pauses in chest compressions spread throughout resuscitative efforts have been associated with worse outcomes by adding to the injury that has accumulated from the no-flow period (35–37). The type of intentional pauses described in this report is thought to harness endogenous repair processes associated with specific mitochondrial protective mechanics (15) and should not be confused with the poor outcomes known to be associated with poor CPR quality that includes prolonged intervals of interrupted chest compressions. In addition, the pauses here should not be confused with the unintentional pauses that happen with the change of rescuers providing compressions during CPR. The controlled pauses described here occur at the initiation of CPR and only for the first 3 minutes of CPR. They last for 20 seconds and are followed by short duration of CPR (another 20 seconds) in well-defined cycles up until the 3rd minute of CPR.

This study has limitations. Rather than determine the potential individual contributions of the two new interventions, adenosine and interruptions in chest compression, we intentionally built upon recent advances with SNPeCPR. Since we added CP to SNPeCPR and adenosine, we cannot yet distinguish the relative contribution of the components to final neurological recovery. Synergy between the pharmacological agents and the mechanical intervention is also possible. New studies are currently investigating the relative contribution of each of these resuscitation components, focusing on markers of mitochondrial protection/injury as well as MRI/histopathology of the brain to correlate the observed clinical neurological findings with the pathophysiology and pathology of injury evolution. Second, we did not add CP to standard CPR and therefore we cannot comment at this time on its potential effect in this setting. In addition we did not test the dosing of adenosine and the controlled pauses. Third, we neither assessed biomarkers of injury for the heart and brain, nor investigated mechanisms in this first report on using CP during CPR.. Although the clinical endpoints reported here, in our opinion, represent higher quality preclinical endpoints than biomarkers, we do not yet know the biochemical processes underlying the tissue protection despite the observed improvement in myocardial and cerebral outcome. We speculate that the protection offered by controlled pauses and adenosine should have similar underlying mechanisms to the ones documented in the acute myocardial infarction and stroke literature (16, 22). However, we tested those interventions exactly as described for acute myocardial infarction and stroke and found them to be extremely effective in our model of cardiac arrest (16, 22). It is also unknown if the benefits demonstrated in this study would be seen with coexisting myocardial ischemia or can be translated to humans. Finally, in our model we used intravenous heparin that was necessary in order to avoid sheath and catheter thrombosis during the long untreated VF which could be a confounding factor.

CONCLUSION

We report high rates of functional neurological and left ventricular recovery after 15 minutes of untreated cardiac arrest in pigs resuscitated with four 20-second pauses during the first 3 minutes of SNPeCPR combined with adenosine.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

The study was funded by an Institutional, Division of Cardiology grant at the University of Minnesota and R01 HL108926-01 NIH grant to Dr. Yannopoulos.

Keith G. Lurie is the founder of Advanced Circulatory Systems Incorporated (ACSI), and co-inventor of the inspiratory impedance threshold device and ACD CPR technique used in this study. Tom P. Aufderheide has board membership for Take Heart America and Citizen CPR Foundation, has consulted for JoLife Medical and Medtronic Foundation, and has received grants/grants pending from the NHLBI Immediate Trial, NHLBI Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium, NINDS Neurological Emergency Treatment Trials Network, and NHLBI Medical College of Wisconsin K12 Research Career Development.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Demetris Yannopoulos is the Medical Director of the Minnesota Resuscitation Consortium, a state wide initiative to improve survival in the state of MN from cardiac arrest. This initiative is sponsored by the Medtronic Foundation and is part of the Heart Rescue Program. There are no conflicts related to this investigation.

References

- 1.Nichol G, Aufderheide TP, Eigel B, et al. Regional systems of care for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:709–729. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181cdb7db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummins RO. From concept to standard-of-care? Review of the clinical experience with automated external defibrillators. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogler S, Sterz F, Sipos W, et al. Distribution of neuropathological lesions in pig brains after different durations of cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1577–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janata A, Bayegan K, Sterz F, et al. Limits of conventional therapies after prolonged normovolemic cardiac arrest in swine. Resuscitation. 2008;79:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janata A, Weihs W, Schratter A, et al. Cold aortic flush and chest compressions enable good neurologic outcome after 15 mins of ventricular fibrillation in cardiac arrest in pigs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1637–1643. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e78b9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kern KB, Hilwig RW, Berg RA, et al. Postresuscitation left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction. Treatment with dobutamine. Circulation. 1997;95:2610–2613. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aufderheide TP, Frascone RJ, Wayne MA, et al. Standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation with augmentation of negative intrathoracic pressure for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:301–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaisance P, Lurie KG, Payen D. Inspiratory impedance during active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a randomized evaluation in patients in cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2000;101:989–994. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolcke BB, Mauer DK, Schoefmann MF, et al. Comparison of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus the combination of active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation and an inspiratory impedance threshold device for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003;108:2201–2205. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095787.99180.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niemann JT, Rosborough JP, Ung S, et al. Hemodynamic effects of continuous abdominal binding during cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou M, Ran Q, Liu Y, et al. Effects of sustained abdominal aorta compression on coronary perfusion pressures and restoration of spontaneous circulation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in swine. Resuscitation. 2011 Aug;82(8):1087–91. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yannopoulos D, Matsuura T, Schultz J, et al. Sodium nitroprusside enhanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation improves survival with good neurological function in a porcine model of prolonged cardiac arrest*. Crit Care Med. 2011:39. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820ed8a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultz JC, Segal N, Caldwell E, et al. Sodium nitroprusside enhanced CPR improves resuscitation rates after prolonged untreated cardiac arrest in two porcine models. Crit Care Med. 2011 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822668ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cour M, Loufouat J, Paillard M, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition to prevent the post-cardiac arrest syndrome: a pre-clinical study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:226–235. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao H. Ischemic postconditioning as a novel avenue to protect against brain injury after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:873–885. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babbitt DG, Virmani R, Forman MB. Intracoronary adenosine administered after reperfusion limits vascular injury after prolonged ischemia in the canine model. Circulation. 1989;80:1388–1399. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.5.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babbitt DG, Virmani R, Vildibill HD, Jr, et al. Intracoronary adenosine administration during reperfusion following 3 hours of ischemia: effects on infarct size, ventricular function, and regional myocardial blood flow. Am Heart J. 1990;120:808–818. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olafsson B, Forman MB, Puett DW, et al. Reduction of reperfusion injury in the canine preparation by intracoronary adenosine: importance of the endothelium and the no-reflow phenomenon. Circulation. 1987;76:1135–1145. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.5.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross AM, Gibbons RJ, Stone GW, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of adenosine as an adjunct to reperfusion in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMISTAD-II) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1775–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao ZQ, Corvera JS, Halkos ME, et al. Inhibition of myocardial injury by ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion: comparison with ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H579–588. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01064.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ovize M, Baxter GF, Di Lisa F, et al. Postconditioning and protection from reperfusion injury: where do we stand? Position paper from the Working Group of Cellular Biology of the Heart of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:406–423. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia S, Henry TD, Wang YL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing postconditioning during ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011;4:92–98. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Chen D, Ma X, et al. Postconditioning in cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a better protocol for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Med Hypotheses. 2009;73:321–323. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yannopoulos D, Matsuura T, McKnite S, et al. No assisted ventilation cardiopulmonary resuscitation and 24-hour neurological outcomes in a porcine model of cardiac arrest*. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:254–260. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b42f6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shultz JJ, Coffeen P, Sweeney M, et al. Evaluation of standard and active compression-decompression CPR in an acute human model of ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 1994;89:684–693. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schultz J, Segal N, Caldwell E, et al. Sodium nitroprusside enhanced CPR improves resuscitation rates after prolonged untreated cardiac arrest in two porcine models. Crit Care Med. 2011 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822668ba. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yannopoulos D, Matsuura T, Schultz J, et al. Sodium nitroprusside enhanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation improves survival with good neurological function in a porcine model of prolonged cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1269–1274. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820ed8a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marino BS, Yannopoulos D, Sigurdsson G, et al. Spontaneous breathing through an inspiratory impedance threshold device augments cardiac index and stroke volume index in a pediatric porcine model of hemorrhagic hypovolemia. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:S398–405. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139950.39972.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinones MA, Waggoner AD, Reduto LA, et al. A new, simplified and accurate method for determining ejection fraction with two-dimensional echocardiography. Circulation. 1981;64:744–753. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.4.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Von Lubitz DK. Adenosine and cerebral ischemia: therapeutic future or death of a brave concept? Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;365:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Von Lubitz DK, Lin RC, Boyd M, et al. Chronic administration of adenosine A3 receptor agonist and cerebral ischemia: neuronal and glial effects. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;367:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00977-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Lubitz DK, Ye W, McClellan J, et al. Stimulation of adenosine A3 receptors in cerebral ischemia. Neuronal death, recovery, or both? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;890:93–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JY, Shen J, Gao Q, et al. Ischemic postconditioning protects against global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury in rats. Stroke. 2008;39:983–990. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.499079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu T, Weil MH, Tang W, et al. Adverse outcomes of interrupted precordial compression during automated defibrillation. Circulation. 2002;106:368–372. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000021429.22005.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg RA, Sanders AB, Kern KB, et al. Adverse hemodynamic effects of interrupting chest compressions for rescue breathing during cardiopulmonary resuscitation for ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2001;104:2465–2470. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.098926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christenson J, Andrusiek D, Everson-Stewart S, et al. Chest compression fraction determines survival in patients with out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;120:1241–1247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.852202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]