Summary

Viral persistence is the rule following infection with all herpesviruses. The β-herpesvirus, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), persists through chronic and latent states of infection. Both the chronic and latent states of infection contribute to HCMV persistence and to the high HCMV seroprevalence worldwide. The chronic infection is poorly defined molecularly, but clinically manifests as low-level virus shedding over extended periods of time and often in the absence of symptoms. Latency requires long-term maintenance of viral genomes in a reversibly quiescent state in the immunocompetent host. In this review, we focus on recent advances in the biology of HCMV persistence, particularly with respect to the latent mode of persistence. Latently infected individuals harbor HCMV genomes in hematopoietic cells and maintain large subsets of HCMV-specific T-cells. In the last few years, impressive advances have been made in understanding virus-host interactions important to HCMV infection, many of which will profoundly impact latency and persistence. We discuss these advances and their known or potential impact on viral latency. As herpesviruses are met with similar challenges in achieving latency and often employ conserved strategies to persist, we discuss current and future directions of HCMV persistence in the context of the greater body of knowledge regarding α-and γ-herpesviruses persistence.

Introduction

Mechanisms of viral persistence are among the most poorly understood phenomena in virology. This is due, in part, to the complexity of multiple layered interactions between the virus, the infected cell and the host organism as a whole that contribute to viral persistence. Persistent viral pathogens are well adapted to their host through co-speciation and tend to have reduced transmissibility and overall pathogenesis relative to viruses adopting acute infection strategies. This suggests that viral persistence as a strategy of coexistence comes at the price of moderating viral replication and, therefore, pathogenesis. As such, HCMV infection is inapparent in the immune-competent host, typically causing no overt pathology. Following infection, HCMV coexists for the lifetime of the host through both chronic virus shedding and latency. The individual contributions of the chronic and latent modes of infection to viral persistence are ill defined.

During the chronic infection, virus is persistently shed from restricted sites in the host at low levels and for extended periods of time. Chronic virus shedding may stem from the acute, primary infection or may result following reactivation of latent virus. Chronic virus shedding may be important for reseeding latent virus reservoirs. In the immune-competent host, the chronic infection is typically asymptomatic and is not associated with overt disease, although it has been associated with inflammatory and age-related disease including vascular disease (Britt, 2008; Drew et al., 2003; Pannuti et al., 1985; Streblow et al., 2008; Zanghellini et al., 1999). Endothelial and epithelial cells are key sites of chronic virus shedding. As an example, HCMV is commonly shed in breast milk in the postpartum period (Stagno et al., 1980). Further, virus may be shed for months to years from epithelial cells in the urinary tract of pediatric patients (Britt, 2008).

The latent infection is defined by a reversibly quiescent state in which viral genomes are maintained, but viral gene expression is highly restricted and no virus is produced. The reversibility of the latent infection, the ability of the virus to reactivate, is critical to the definition of latency as this feature distinguishes latency from an abortive infection. Importantly, loss of T-cell-mediated immune control or changes in the differentiation or activation state of cells harboring latent HCMV can result in reactivation of latent virus and production of viral progeny. While isolated reactivation events likely occur intermittently in the immune-competent host, these events are controlled by existing T cell-mediated immunity and do not result in clinical presentation. Severe HCMV disease is associated with reactivation of latent virus and chronic infection associated with states of insufficient T-cell control following stem cell or solid organ transplantation, HIV infection, and intensive chemotherapy regimens for cancer (Boeckh and Geballe, 2011; Britt, 2008).

Despite decades of research, we have little more than a cursory understanding of the molecular basis of HCMV latency and how viral, cellular, and organismal mechanisms are orchestrated to meet this objective. Efforts to understand HCMV latency are hampered by the restriction of HCMV to the human host. While HCMV infects a diverse number of cell types, latency is unique to specific cell types. Therefore, the current state of our knowledge is primarily borne from the use of primary human cell culture models, specifically those using primary hematopoietic progenitor (HPCs) or myeloid lineage cells and cell line models including the myeloid THP-1 and N-teratocarcinoma (T2) cell lines. Due to limitations in cell culture models, murine (MCMV) (reviewed in, (Reddehase et al., 2002), rat (RCMV) (reviewed in, (Streblow et al., 2008), guinea-pig (reviewed in, (Schleiss, 2006), and the rhesus (RhCMV) viruses (reviewed in, (Powers and Fruh, 2008) are important models in understanding persistence in the context of the immunocompetent host (Kern, 2006). Despite the value of these animal models, differences in the genome content, coding capacity, and aspects of pathogenesis between HCMV and these viruses command studies using the human virus to understand unique mechanisms of persistence that arose through co-speciation.

Virus-coded determinants

Of the nearly 200 genes encoded by HCMV, less than one-fourth are essential for viral replication and conserved across herpesvirus subfamilies. Gene products for 37–60 open reading frames (ORFs) (depending on methods used) are detected following in vitro infection of CD34+ HPCs (Cheung et al., 2006; Goodrum et al., 2004). Gene products detected in CD34+ HPCs include the immediate early (IE1-72kDa and IE2-86kDa) transcripts (Cheung et al., 2006; Goodrum et al., 2004; Goodrum et al., 2002; Petrucelli et al., 2009) and proteins, which are transiently detected in CD34+ HPCs (Petrucelli et al., 2009; Umashankar et al., 2011) as well as in CD14+ cells (Hargett and Shenk, 2010). Despite transient expression of IE genes, the full repertoire of genes required for replication is not detected. Indeed, the majority of ORFs expressed in CD34+ HPCs are non-essential for productive viral replication in fibroblasts and their function is unknown (Yu et al., 2003). Consistent with these findings, RCMV patterns of gene expression are defined by the cell type infected (Streblow et al., 2007). Due to limitations in current latency models, viral gene expression has not been globally analyzed following the establishment of latency. However, several viral gene products reviewed in the following subsections have been detected in HPCs or myeloid cells from sero-positive individuals.

CMV latency-associated transcripts

Transcripts and proteins encoded from a region encompassing the major immediate early region are detected in hematopoietic cells following infection in vitro as well as in latently infected individuals (Kondo et al., 1996; Landini et al., 2000). It should be noted that the structure of these transcripts differ from those produced during a productive infection in fibroblasts. While the role of these transcripts in infection is not known, the encoded ORF94 protein is dispensable for establishing latency in granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells infected in vitro (White et al., 2000). However, ORF94 inhibits interferon-induced 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) during infection in fibroblasts (Tan et al., 2011), an activity also attributed to TRS1 and IRS1(Child et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2009). As discussed in later sections, intrinsic and innate defenses to viral infection represents an important control point that impacts viral persistence.

cmvIL-10

The UL111A gene encodes a viral interleukin-10 homolog, cmvIL-10, with 27% identity to human IL-10 (Jenkins et al., 2004). While cmvIL-10 is not required for the establishment of the latent infection in vitro (Cheung et al., 2009), roles for cmvIL-10 in modulating cellular differentiation, cytokine production, and the immune response were recently described and may underlie an important role for cmvIL-10 in persistence. cmvIL-10 suppresses proinflammatory cytokine production (Avdic et al., 2011) and inhibits the differentiation of infected progenitors into dendritic cells (Reeves et al., 2005). As dendritic cells provide a permissive environment for viral replication, this activity may contribute to maintenance of latency and a latent reservoir. cmvIL-10 may also compromise dendritic cell (DC) function to limit immune clearance of the virus. Further, cmvIL-10 decreases MHC class II expression in CD34+ HPCs and limits CD4+ T-cell recognition of infected cells (Cheung et al., 2009).

The RhCMV viral IL-10 orthologue dampens the innate immune response by decreasing the overall number of infiltrating immune cells thereby reducing the quality of the ensuing adaptive response (Chang and Barry, 2010). Consistent with a contribution IL-10-like activity to latency, cellular IL-10 has been shown to restrict CMV-specific memory T-cell inflation and increases the latent load during infection with MCMV, which does not encode a viral IL-10 (Jones et al., 2010). Intriguingly, HCMV-infected CD34+ HPCs express increased cellular IL-10 due to decreased expression of the cellular miRNA targeting IL-10, hsa-miR-92a (Poole et al., 2011). These results suggest that in addition to cmvIL-10, HCMV has other mechanisms to modulate IL-10 activity to favor a latent state. Taken together, these findings suggest an important role for IL-10, whether encoded by the virus or by the host cell, in shaping the immune response to cytomegalovirus infection and maintaining the latent infection.

UL133-UL138 locus

The UL133-UL138 locus is encoded within the ULb′ region of the genome that is unique to clinical isolates of HCMV. The UL133-UL138 locus is defined as a regulator of infection outcomes as the loss of this locus results in three context-dependent phenotypes; it is dispensable for replication in fibroblasts, suppresses replication in hematopoietic cells and is required for replication in primary endothelial cells (Umashankar et al., 2011). The protein encoded by UL138, pUL138, was originally identified as a viral determinant important for the establishment and/or maintenance of a latent infection in CD34+ HPCs infected in vitro (Goodrum et al., 2007; Petrucelli et al., 2009). pUL138 is expressed during both productive and latent infections in a variety of cell types (Petrucelli et al., 2009; Reeves and Sinclair, 2010; Umashankar et al., 2011) and UL138 transcripts are detected in CD34+ and CD14+ cells from latently infected individuals (Goodrum et al., 2007).

pUL138 is expressed from multiple polycistronic transcripts also encoding pUL133, pUL135, and pUL136 (Grainger et al., 2010; Petrucelli et al., 2009). While the roles of pUL135 and pUL136 are not yet known in infection, pUL133 functions similarly to pUL138 in that the disruption of the genes encoding either of these proteins results in increase replicative efficiency in CD34+ HPCs infected in vitro (Umashankar et al., 2011). As pUL133, pUL135, pUL136, and pUL138 are expressed together from polycistronic transcripts and localize together in the Golgi (Umashankar et al., 2011), these proteins likely function coordinately in viral infection. Given the localization of pUL133, pUL135, pUL136, and pUL138 to the secretory pathway, they may play unique roles in persistence that have not been described for other herpesviruses. The UL133-UL138 locus is conserved in chimpanzee CMV (ChCMV), but orthologues are absent in viruses infecting lower mammals and, therefore, may represents a novel primate host-specific viral adaptation acquired through co-speciation (Umashankar et al., 2011).

Two groups have recently shown that pUL138 enhances cell surface levels of tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) (Le et al., 2011; Montag et al., 2011). This action restores susceptibility of HCMV-infected cells to TNF-α-induced activation of NFκB. pUL138 expression during the context of infection or overexpression in reporter assays both result in modest increases in major immediate early promoter activation and immediate early protein (IE1-72kDa and IE2-86kDa) accumulation (Petrucelli et al., 2009), an activity that is enhanced by treatment with TNF-α (Montag et al., 2011). The role of pUL138 in sensitizing cells to TNF-α-mediated activation of NFκB and subsequent IE gene expression is consistent with a proposed role in reactivation of viral gene expression (Montag et al., 2011). However, this model is inconsistent with the demonstrated role for pUL138 in suppressing viral replication to promote latency in CD34+ HPCs (Goodrum et al., 2007; Petrucelli et al., 2009; Umashankar et al., 2011). While it is yet unclear what role NFκB plays in HCMV latency or reactivation, the activation of NFκB is critically important for stabilizing γ-herpesvirus latency, including that of Epstein Barr Virus (EBV), Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), and murine γ-68 virus (Speck and Ganem, 2010).

US28

US28 is one of four G protein-coupled receptors expressed by HCMV and has homology to CC-chemokine receptors (Gao and Murphy, 1994). US28 binds multiple CC-chemokines, including RANTES, MCP-1, MIP1α, and MIP-1β and the CX3C-chemokine Fractalkine (Kuhn et al., 1995). In addition to productive infections, US28 expression is detected in latently infected individuals as well as in the THP-1 monocytic cell line infected in vitro (Beisser et al., 2001). US28 expression in monocytes increases IL-8 secretion and alters the adhesion and migration of these cells suggesting that it may contribute to the dissemination of latently infected cells (Randolph-Habecker et al., 2002). Further, fractalkine stimulation of macrophages expressing US28 induces migration, but not in smooth muscle cells, indicating cell-type specific functions of US28 (Vomaske et al., 2009). Taken together, these findings suggest an important role for US28-mediated signaling in virus dissemination. US28 activates signaling and cell proliferation through IL-6-JAK1-STAT3 signaling axis (Slinger et al., 2010). Consistent with this activity, transgenic mice expressing US28 develop neoplasia and have increased susceptibility to inflammatory-induced tumors (Bongers et al., 2010).

Luna

Transcripts antisense to the UL81-UL82 encode the 16-kDa latent undefined nuclear antigen, LUNA. LUNA transcripts and antibodies against the protein are detected in monocytes derived from latently-infected individuals (Bego et al., 2005; Bego et al., 2011). While the function of this protein in infection is undetermined, transcript levels of Luna diminish as immediate early transcripts increase during differentiation of CD34+ cells into dendritic cells and reactivation (Reeves and Sinclair, 2010). As is true of the major immediate early genes, LUNA expression depends on IE1-72kDa to relieve Daxx/ATRX-mediated repression of the LUNA promoter (Reeves et al., 2010).

CMV-miRNAs

Eleven microRNAs (miRNAs) are encoded throughout the HCMV genome (Grey et al., 2005). While many cmv-miRNA targets are unknown, miR-UL112 targets the major immediate early transcript encoding the IE1-72kDa regulator protein (Grey et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2008). miR-UL112 also targets UL114, reducing its activity as a uracil DNA glycosylase (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009). Consistent with these activities, miR-UL112 inhibits viral replication in fibroblasts (Grey et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2008) and could favor the establishment of latency. Intriguingly, miR-UL112 also functions to avert natural killer cell recognition by targeting the cellular stress-inducible MICB ligand for the NKG2D activating receptor (Nachmani et al., 2010; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2007). Taken together, this work begins to define an elegant mechanism by which miR-UL112 may coordinately downmodulates viral replication and the immune response for viral persistence. Two additional HCMV-coded miRNAs, miR-US25-1 and miR-US25-2, inhibit viral DNA synthesis and viral replication of HCMV (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009). Similar to these findings for HCMV, HSV-1 expresses at least two miRNAs in latently infected neurons that target the ICP0 and ICP4, and therefore, may contribute to the establishment and maintenance of latency by inhibiting immediate early and early gene expression (Umbach et al., 2008). Herpesvirus-coded miRNAs offer an intriguing potential for regulating viral infection for latency and provide an attractive mechanism that does not require expression of a protein antigen. Studies in rats using RCMV demonstrate that viral miRNA expression is tissue specific dependent and that some are uniquely expressed during states of viral persistence (Meyer et al., 2011).

The balance of cellular responses to infection and viral countermeasures

HCMV masterfully evades all levels of the host response to infection, including intrinsic, innate and adaptive responses. Further, HCMV skillfully manipulates cellular controls including regulation of the cell cycle and gene silencing. Overcoming cellular defenses and control of proliferation and gene expression is essential for successful viral replication and persistence. Therefore, the suppressive forces provided by cellular defenses and controls may aid the establishment of latency. The balance between the virus-host interactions centered around these cellular responses depend on the context of infection and the repertoire of viral genes expressed. The following subsections will discuss aspects of cell biology that necessarily or potentially impact viral persistence.

Intrinsic defenses

As intrinsic cellular defenses stand ready to respond at the point of virus binding to the cell surface, they represent an exceptionally important control point for viral infection. These defenses include cellular restriction factors that are constitutively expressed and active independent of pathogen encounter. Viruses that are unable to adequately disarm these defenses ultimately fail to replicate productively (reviewed in, (Bieniasz, 2004). By extension, these defenses could provide a pressure for the virus to establish a latent infection in cell types where the full complement of viral factors required for disarmament are either not expressed or not functional.

Nuclear domain 10 (ND10), also referred to as PML oncogenic domains (PODs) or PML nuclear bodies are dynamic proteinacious structures comprised of PML, Sp100, hDaxx, and ATRX, which play key roles in the intrinsic defense to viral infection. ND10s are juxtaposed with viral genomes, which become viral centers of genome synthesis and replication (Maul, 1998, 2008). Recent studies demonstrate a dynamic relationship between ND10s and viral infection, suggesting that ND10s are recruited to viral genomes (Dimitropoulou et al., 2010; Tavalai et al., 2006). The proteins associated with ND10s negatively impact HCMV replication (Lukashchuk et al., 2008; Saffert and Kalejta, 2006; Tavalai et al., 2011; Tavalai et al., 2006; Tavalai et al., 2008; Tavalai and Stamminger, 2011; Woodhall et al., 2006). The importance of ND10 to antiviral defense is exemplified in the fact that multiple families of viruses encode functions to disperse or degrade ND10 components including adenovirus, papillomavirus, polyomavirus, and arenavirus, in addition to herpesvirus family members (Ahn and Hayward, 1997; Everett and Chelbi-Alix, 2007; Korioth et al., 1996; Tavalai and Stamminger, 2008). In HCMV, both the tegument protein pp71 and IE1-72-kDa function to disrupt ND10s (reviewed in, (Maul, 2008; Tavalai and Stamminger, 2011).

The viral tegument protein, pp71, is important during the initial stages (prior to viral gene expression) of infection in establishing a permissive cellular environment for viral replication. pp71 facilitates transactivation of the major immediate early promoter (MIEP) by degrading the cellular repressor hDaxx and evicting ATRX from ND10 (Cantrell and Bresnahan, 2005, 2006; Hwang and Kalejta, 2007; Ishov et al., 2002; Preston and Nicholl, 2006; Saffert and Kalejta, 2006, 2007), thereby preventing chromatinization and repression of the MIEP (Woodhall et al., 2006). While this strategy facilitates activation of the MIEP for replication in fibroblasts, pp71 is retained in the cytoplasm and cannot inactivate hDaxx in the Ntera2 and THP-1 cell lines or CD34+ HPCs (Saffert and Kalejta, 2007; Saffert et al., 2010). Artificial knockdown of hDaxx permits immediate early gene expression in these cells. This provides a possible strategy by which the viral chromosome is repressed epigenetically in hematopoietic cells for latency. These findings suggest that ND10 disruption is a pivotal control point in controlling the outcome of infection. Consistent with a possible role in creating a repressive environment important for viral latency, cells latently infected with EBV have intact ND10s and their dispersal is coincident with lytic replication (Bell et al., 2000).

Many viral activities associated with viral entry to replication of progeny virions trigger programmed cell death or apoptosis. Certainly, the activation of intrinsic defenses will ultimately result in apoptosis without viral-mediated intervention. HCMV actively subvert apoptosis during the productive infection through the action of several virus-coded inhibitors of apoptosis, including IE1and IE2, UL36/vICA, UL37 exon 1/vMIA and UL38 (Brune, 2011). It is not known if these anti-apoptotic factors play a role in inhibiting cell death during latency. Two groups have recently demonstrated the HCMV infection upregulates myeloid cell leukemia protein-1 (Mcl-1) (Chan et al., 2010; Reeves et al., 2012), a member of the Bcl-2 family which is important for myeloid cell survival. Mcl-1 activation was dependent on PI3K (Chan et al., 2010) or MAPK/ERK (Reeves et al., 2012) signaling initiated during early events in infection. These differing results suggest that multiple signaling pathways may lead the same result, perhaps depending on the cell type infected. Subverting cell death pathways to ensure successful productive and latent infections is critical to all herpesviruses (Kaminskyy and Zhivotovsky, 2010).

Epigenetics

Once latency is established, the HCMV genome is presumably maintained as a chromatinized episome. Epigenetic regulation is a key mechanism in regulating viral genome expression during herpesvirus replication and latency (Bloom et al., 2010; Knipe and Cliffe, 2008; Nevels et al., 2011; Paulus et al., 2010; Takacs et al., 2010). During productive infection, all four core histones associate with the HCMV genome, and while nucleosome occupancy remains low, it is dynamic (Nitzsche et al., 2008), as has also been shown for KSHV (Toth et al., 2010) and HSV-1 (Cliffe and Knipe, 2008). Low nucleosome occupancy during productive viral replication is likely mediated by viral gene products that prevent deposition or promote eviction of nucleosomes, as has been shown for a number of herpesviruses (reviewed in, (Paulus et al., 2010) (Reeves et al., 2006). Virus-coded latency determinants may also play an active role in chromatinizing the genome during latency (Giordani et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2005).

Studies in cell lines supporting a latent-like HCMV infection or CD34+ HPCs, demonstrate that the MIEP is associated with repressive heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) and deacetylated histones (Murphy et al., 2002; Reeves et al., 2005), while the LUNA promoter is associated with activated acetylated histones (Reeves and Sinclair, 2010). While HCMV awaits a global characterization of the epigenetic signature of latency, epigenetic regulation of HSV-1 and KSHV has been more extensively studied (Cliffe et al., 2009; Kwiatkowski et al., 2009; Toth et al., 2010). From these studies, it is clear that latent genomes are not devoid of activating histone modifications (H3K9/K14-ac and H3K4-me3), but that polycomb group proteins concomitantly modify viral genomes with H3K27-me3, which represses transcription in the presence of activating marks (Gunther and Grundhoff, 2010; Toth et al., 2010). Bivalently modified viral genomes allow the genome to persist in a reversibly heterochromatin state poised for reactivation and reveal the difficulty in ascertaining the importance of any individual histone modification without considering the composite of the epigenetic landscape.

Signaling Pathways

Pathways of cell signaling are critical to modulating the state of the cell and ultimately the host organism. HCMV initiates and mediates cellular signaling both prior to and following viral gene expression (Yurochko, 2008). In the first tier, signaling is initiated by viral glycoprotein interaction with cellular receptors and by constituents of the viral tegument following infection. In a second tier, cellular signaling may be initiated and modulated by viral gene products during the course of infection. Just as viral-mediated signaling is critical for successful viral replication, cellular signaling events will also contribute importantly to creating a cellular environment permissive for latency. Within the first hour of infection in monocytes, HCMV stimulates a downstream signaling event involving increased pEGFR, PI3K activity and MAPK activity (Bentz and Yurochko, 2008). The PI3K signaling is crucial for upregulating active actin nucleator, N-WASP, to induce monocyte motility, an activity favoring hematogenous dissemination and persistence (Chan et al., 2009). HCMV’s upregulation of PI3K signaling also increases Mcl-1, a Bcl-2 member, that inhibits apoptosis post infection (Chan et al., 2010). The signaling pathways initiated during HCMV infection are unique to cell type. For example, HCMV induced phosphorylation of EGFR is transient in fibroblasts and trophoblasts but chronic in endothelial cells (Bentz and Yurochko, 2008; LaMarca et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2003).

While HCMV clearly alters cellular signaling pathways through interaction with cellular receptors and early events following viral entry, HCMV also encodes transactivating proteins and viral receptors with the ability to modulate cellular signaling through the course of infection. As discussed previously, US28 is an HCMV-coded G-protein coupled receptor. US28-mediated chemokine signaling events enhance macrophage migration, which likely contributes to viral dissemination and persistence (Vomaske et al., 2009). The role of viral receptors, signaling decoys or homologues in latency represents an important frontier for further work. It will be critical to understand how cellular signaling pathways and the viral modulation of those pathways are integrated to influence outcomes of infection and viral persistence.

Inflammatory, stress, and differentiation signals are tightly associated with viral reactivation due to a high density of NFκB, AP1, and CRE transcription factor binding sites in the MIEP (Meier and Stinski, 2006). HCMV dramatically alters the transcriptome of infected monocytes favoring a pro-inflammatory state and differentiation into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages (Chan et al., 2008a; Chan et al., 2008b). Further, reactivation of the MIEP in NT2 cells can occur through PKCδ signaling and depends on CREB and NFκB binding sites in the MIEP (Liu et al., 2010) or through the PKA-CREB-TORC2 signaling axis (Yuan et al., 2009). HCMV reactivation in DC is associated with IL-6 activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway (Reeves and Compton, 2011).

As CMV initiates signaling cascades in a variety of cells, it is likely that viral-induced or -mediated signaling may also be important for creating an environment permissive for latency in ways that are not yet understood. CMV may differentially mediate signaling pathways depending on the cell type infected and the repertoire of viral genes expressed. Consistent with a key role for signaling in the establishment and maintenance of HCMV latency, latency membrane protein 1 (LMP1) of Epstein Barr virus activates EGFR, ERK, and STAT3 (Kung et al., 2011) and NFκB activation is critical forγ-herpesvirus latency (reviewed in, (Speck and Ganem, 2010). A comprehensive understanding of the signaling events that support HCMV latency awaits further investigation.

Cell cycle regulation

Cell cycle and checkpoint control is intimately connected to the outcome of herpesvirus infection. The complexity inherent to this virus-host interaction is becoming evermore apparent. G1/G0 cells, but not S/G2 cells, are permissive to HCMV IE expression and viral replication (Sanchez and Spector, 2008). It has been recently shown that high CDK activity, but not PML or Daxx, is the basis for the block to replication in S/G2 (Zydek et al., 2010; Zydek et al., 2011). The block is overcome by inhibiting CDK activity either through inducing p21waf1/cip1 or treating cells with the CDK inhibitor, roscovitine. Treatment with roscovatine also relieves repression of the MIEP in NT2 cells (Zydek et al., 2010). Consistent with these findings, productive EBV replication requires the accumulation of p53 and p21waf1/cip1. The EBV BXLF1 protein both positively and negatively affects p53 levels, a function that may constitute a mechanism by which BXLF1 modulates the switch between latent and productive infection (Sato et al., 2010). Similarly, Tip60, a component of an acetyltransferase complex and upstream regulator of the DNA damage response, is activated by the BGLF 4 kinase in EBV infection and is required for efficient EBV replication (Li et al., 2011). For HCMV, pUL27 has recently been shown to induce p21waf1/cip1 by degrading Tip60 (Reitsma et al., 2011), positively implicating the DNA damage repair pathway and cell cycle arrest in viral replication. These studies suggest a pivotal role for cell cycle checkpoints in modulating permissivity to IE gene expression and possibly regulating the balance between latent and productive states of infection.

Subversion of T-cell recognition

T-cell surveillance plays a critical role in maintenance of viral latency, as reactivation from latency and HCMV disease is associated with a loss of T-cell immunity. HCMV is a master of evading immune recognition and elimination by CD8+ T cells and NK cells. This is achieved through the action of a number of genes involved in the preventing activation of NK cells and downregulating viral antigen presentation by the major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I). The importance of this defense is exemplified in that HCMV encodes six gene products to impede antigen presentation, including US2, US3, US6, US8, U10, and US11, and a number of diverse proteins and miRNAs to evade NK cell recognition (Powers et al., 2008). While it is easy to envision an essential role for viral evasion of MHC-I antigen presentation in the primary infection, recent work reveals that the concerted action of rhCMV orthologues of the HCMV MHC-I evasion proteins is dispensable for the primary infection in rhesus macaques (Hansen et al., 2010). Nevertheless, these genes are required for HCMV superinfection, suggesting an important role in viral persistence by permitting continual reinfection or by averting immune recognition of reactivating virus.

Despite possessing an exquisite ability to escape antigen presentation and T-cell-mediated clearance, infected individuals maintain exceptionally large populations of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells specific to HCMV. If these inflated T-cell populations are dysfunctional and contribute to an “immune risk” phenotype, then these findings suggest that HCMV persistence ultimately has a deleterious impact on the host. Recent studies to define immune senescence and the role of CMV in immune senescence in CMV infected humans, rhesus macaques, and mice, illustrate the complexity of these questions (reviewed in, (Wills et al., 2011). Understanding the complicated relationship between HCMV and the host immune response will contribute importantly to our understanding of viral persistence.

Future Directions

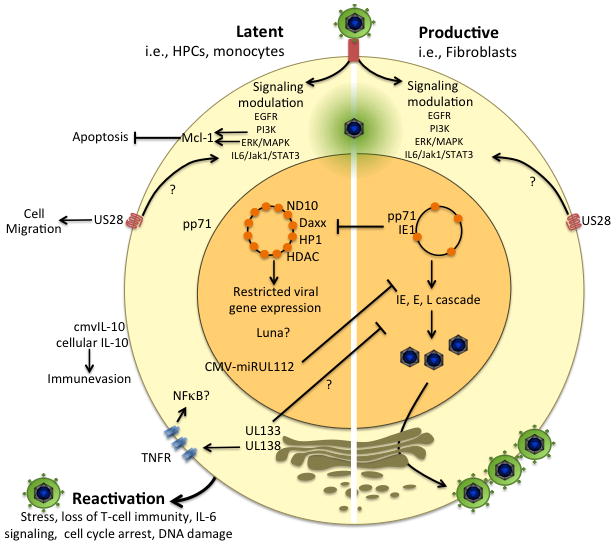

Herpesvirus latency, and particularly that of HCMV, is the sum total of intricate and multi-layered interactions between the virus and host (Figure 1). While it is clear that both viral and host mechanisms contribute to persistence, we do not yet have comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms and molecular components involved. Further, how the individual contributions of viral and cellular mechanisms are integrated for viral persistence is not well understood and is the standing challenge for going forward. In the last decade, a number of viral factors and cellular processes have been associated with the latent infection. Understanding how these factors function and how the balance of replication promoting and replication suppressing factors is regulated in infection represents a critical next step in understanding mechanisms of viral persistence.

Figure 1. Key virus-cell interactions contributing to viral fate decisions.

The outcome of infection is dictated through complex and opposing virus-host interactions that promote cellular states that are permissive or restrictive to viral replication. Signaling events initiated either upon viral entry or following viral gene expression are undoubtedly critical to establishing cellular environments for productive replication or latency. The cellular Mcl-1 survival protein is upregulated in cells that support a latent infection by PI3K or MAPK/ERK activation. US28 is a viral chemokine receptor homologue that functions importantly in signaling during both productive and latent states of infection, and may promote viral dissemination by upregulating monocyte and macrophage motility. US28 activates IL6/JAK1/STAT3 signaling but the impact of this action on the productive or latent infections are not known. Transport of the pp71 tegument protein into the nucleus is critical to intrinsic ND10 defenses and chromatinization of the virus genome to permit viral gene expression. Retention of pp71 in the cytoplasm and a failure to disarm ND10 defenses may contribute to latency. The IE1-72kDa gene product also functions to inhibit intrinsic ND10 defenses and innate defenses for productive replication. Further, latency-associated viral determinants including UL133-UL138 and miR-UL112 impede viral replication to favor the latent state. miR-UL112 directly inhibits IE gene expression, but the mechanism by which UL133-UL138 suppresses viral replication is not know. While UL138 enhances TNFR on the cell surface, how this activity and subsequent activation of NFκB contributes to the latent HCMV infection is not known. miR-UL112 and cmvIL-10 function to assuage the immune response to latently infected cells. The outcome of infection is highly dependent upon the cell type infected. While other reservoirs of latent and productive infection exist (i.e, endothelial, epithelial), molecular aspects of persistence in these cells have not yet been thoroughly investigated. For some pathways and determinants indicated in the diagram, mechanistic details or the precise role in latency are not fully know, as indicated by the question mark.

Most fundamental to the understanding of HCMV persistence is the cellular reservoirs for chronic virus shedding and latent genome maintenance in the infected host. While HCMV infects a wide variety of cells in the human host, not all cells are permissive for latency and reservoirs of latency remain to be definitively defined in the human host. The majority of latency studied have focused on hematopoietic cells; however, other cell types, including endothelial and epithelial cells, remain important reservoirs that contribute to persistence in ways that are not well understood. Work to define reservoirs of latency and chronic infection is important for understanding cell type-specific interactions culminating in viral persistence and to identify targets for antiviral strategies aimed at latently infected cells.

Confinement of HCMV latency studies to cultured cells represents the greatest impediment to understanding the mechanisms fundamental to HCMV persistence in the host. New models, including humanized mice, will permit studies in an intact organism where components of the human host and immune system can be explored (Smith et al., 2010). In addition to appropriate animal models, it is also important to advance relevant primary cell or cell line models to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying latency. Many latency models have used induction of IE gene expression as a marker of reactivation. While this certainly indicates reactivation of IE gene expression, it is problematic as a measure of full reactivation from latency. As elegantly shown in MCMV, resuming IE gene expression is only the first step in a cascade of events that are required to productively reactivate viral replication (Kurz et al., 1999). As the detection of IE transcripts may reflect nonproductive reactivation, recovery of infectious virus should remain the gold standard for measuring reactivation.

Taking lessons from the α- and γ-herpesviruses, it will be critical to understand how epigenetic, cellular stress and signaling pathways contribute to an intracellular state required for latency and how the virus may tweak these pathways for the purpose of latency or reactivation. While taken as true, the existence of an episomal genome is largely inferred and the mechanisms by which it is maintained and replicated in latently infected cells are not known. Future studies aimed at understanding regulation of the viral chromosome offer the exciting promise of further advancing our understanding of how cellular intrinsic defense, DNA damage repair pathways, and nuclear architecture converge at an epigenetic point of control for infection. Emerging technologies and discovery-based approaches, including next generation sequencing and quantitative proteomics, combined with refined cellular models will be critical to for understanding how complex host-virus interactions converge and contribute to viral persistence. Through advanced technologies and refined models, we will define the key virus-host interactions underlying states of infection important to viral persistence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We apologize to our colleagues whose publications were not cited due to space limitations. F. Goodrum is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences and is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

References

- Ahn JH, Hayward GS. The major immediate-early proteins IE1 and IE2 of human cytomegalovirus colocalize with and disrupt PML-associated nuclear bodies at very early times in infected permissive cells. J Virol. 1997;71:4599–4613. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4599-4613.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avdic S, Cao JZ, Cheung AK, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. Viral Interleukin-10 Expressed by Human Cytomegalovirus during the Latent Phase of Infection Modulates Latently Infected Myeloid Cell Differentiation. J Virol. 2011;85:7465–7471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00088-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bego M, Maciejewski J, Khaiboullina S, Pari G, St Jeor S. Characterization of an antisense transcript spanning the UL81–82 locus of human cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2005;79:11022–11034. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11022-11034.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bego MG, Keyes LR, Maciejewski J, St Jeor SC. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated protein LUNA is expressed during HCMV infections in vivo. Arch Virol. 2011;156:1847–1851. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisser PS, Laurent L, Virelizier JL, Michelson S. Human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor gene US28 is transcribed in latently infected THP-1 monocytes. J Virol. 2001;75:5949–5957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5949-5957.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell P, Lieberman PM, Maul GG. Lytic but not latent replication of epstein-barr virus is associated with PML and induces sequential release of nuclear domain 10 proteins. J Virol. 2000;74:11800–11810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11800-11810.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentz GL, Yurochko AD. Human CMV infection of endothelial cells induces an angiogenic response through viral binding to EGF receptor and beta1 and beta3 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5531–5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800037105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieniasz PD. Intrinsic immunity: a front-line defense against viral attack. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DC, Giordani NV, Kwiatkowski DL. Epigenetic regulation of latent HSV-1 gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckh M, Geballe AP. Cytomegalovirus: pathogen, paradigm, and puzzle. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:1673–1680. doi: 10.1172/JCI45449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers G, Maussang D, Muniz LR, Noriega VM, Fraile-Ramos A, Barker N, Marchesi F, Thirunarayanan N, Vischer HF, Qin L, et al. The cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28 promotes intestinal neoplasia in transgenic mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:3969–3978. doi: 10.1172/JCI42563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt W. Manifestations of human cytomegalovirus infection: proposed mechanisms of acute and chronic disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:417–470. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune W. Inhibition of programmed cell death by cytomegaloviruses. Virus Res. 2011;157:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell SR, Bresnahan WA. Interaction between the human cytomegalovirus UL82 gene product (pp71) and hDaxx regulates immediate-early gene expression and viral replication. J Virol. 2005;79:7792–7802. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7792-7802.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell SR, Bresnahan WA. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) UL82 gene product (pp71) relieves hDaxx-mediated repression of HCMV replication. J Virol. 2006;80:6188–6191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02676-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan G, Bivins-Smith ER, Smith MS, Smith PM, Yurochko AD. Transcriptome analysis reveals human cytomegalovirus reprograms monocyte differentiation toward an M1 macrophage. J Immunol. 2008a;181:698–711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan G, Bivins-Smith ER, Smith MS, Yurochko AD. Transcriptome analysis of NF-kappaB- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-regulated genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected monocytes. J Virol. 2008b;82:1040–1046. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00864-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan G, Nogalski MT, Bentz GL, Smith MS, Parmater A, Yurochko AD. PI3K-dependent upregulation of Mcl-1 by human cytomegalovirus is mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor and inhibits apoptosis in short-lived monocytes. J Immunol. 2010;184:3213–3222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan G, Nogalski MT, Yurochko AD. Activation of EGFR on monocytes is required for human cytomegalovirus entry and mediates cellular motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22369–22374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908787106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WL, Barry PA. Attenuation of innate immunity by cytomegalovirus IL-10 establishes a long-term deficit of adaptive antiviral immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22647–22652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013794108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AK, Abendroth A, Cunningham AL, Slobedman B. Viral gene expression during the establishment of human cytomegalovirus latent infection in myeloid progenitor cells. Blood. 2006;108:3691–3699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-026682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AK, Gottlieb DJ, Plachter B, Pepperl-Klindworth S, Avdic S, Cunningham AL, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. The role of the human cytomegalovirus UL111A gene in down-regulating CD4+ T-cell recognition of latently infected cells: implications for virus elimination during latency. Blood. 2009;114:4128–4137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-197111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child SJ, Hakki M, De Niro KL, Geballe AP. Evasion of cellular antiviral responses by human cytomegalovirus TRS1 and IRS1. J Virol. 2004;78:197–205. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.197-205.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe AR, Garber DA, Knipe DM. Transcription of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript promotes the formation of facultative heterochromatin on lytic promoters. J Virol. 2009;83:8182–8190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00712-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe AR, Knipe DM. Herpes simplex virus ICP0 promotes both histone removal and acetylation on viral DNA during lytic infection. J Virol. 2008;82:12030–12038. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01575-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulou P, Caswell R, McSharry BP, Greaves RF, Spandidos DA, Wilkinson GW, Sourvinos G. Differential relocation and stability of PML-body components during productive human cytomegalovirus infection: detailed characterization by live-cell imaging. European journal of cell biology. 2010;89:757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew WL, Tegtmeier G, Alter HJ, Laycock ME, Miner RC, Busch MP. Frequency and duration of plasma CMV viremia in seroconverting blood donors and recipients. Transfusion. 2003;43:309–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett RD, Chelbi-Alix MK. PML and PML nuclear bodies: implications in antiviral defence. Biochimie. 2007;89:819–830. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JL, Murphy PM. Human cytomegalovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional beta chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28539–28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordani NV, Neumann DM, Kwiatkowski DL, Bhattacharjee PS, McAnany PK, Hill JM, Bloom DC. During herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of rabbits, the ability to express the latency-associated transcript increases latent-phase transcription of lytic genes. J Virol. 2008;82:6056–6060. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02661-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrum F, Jordan CT, Terhune SS, High KP, Shenk T. Differential outcomes of human cytomegalovirus infection in primitive hematopoietic subpopulations. Blood. 2004;104:687–695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrum F, Reeves M, Sinclair J, High K, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus sequences expressed in latently infected individuals promote a latent infection in vitro. Blood. 2007;110:937–945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrum FD, Jordan CT, High K, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression during infection of primary hematopoietic progenitor cells: a model for latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16255–16260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252630899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger L, Cicchini L, Rak M, Petrucelli A, Fitzgerald KD, Semler BL, Goodrum F. Stress-Inducible Alternative Translation Initiation of Human Cytomegalovirus Latency Protein pUL138. J Virol. 2010;84:9472–9486. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00855-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey F, Antoniewicz A, Allen E, Saugstad J, McShea A, Carrington JC, Nelson J. Identification and characterization of human cytomegalovirus-encoded microRNAs. J Virol. 2005;79:12095–12099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12095-12099.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey F, Meyers H, White EA, Spector DH, Nelson J. A human cytomegalovirus-encoded microRNA regulates expression of multiple viral genes involved in replication. PLoSPathogens. 2007 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030163. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther T, Grundhoff A. The epigenetic landscape of latent Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000935. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SG, Powers CJ, Richards R, Ventura AB, Ford JC, Siess D, Axthelm MK, Nelson JA, Jarvis MA, Picker LJ, et al. Evasion of CD8+ T cells is critical for superinfection by cytomegalovirus. Science. 2010;328:102–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1185350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargett D, Shenk TE. Experimental human cytomegalovirus latency in CD14+ monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20039–20044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014509107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Kalejta RF. Proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of Daxx by the viral pp71 protein in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Virology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishov AM, Vladimirova OV, Maul GG. Daxx-mediated accumulation of human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 at ND10 facilitates initiation of viral infection at these nuclear domains. J Virol. 2002;76:7705–7712. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7705-7712.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. A Novel Viral Transcript with Homology to Human Interleukin-10 Is Expressed during Latent Human Cytomegalovirus Infection. J Virol. 2004;78:1440–1447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1440-1447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Ladell K, Wynn KK, Stacey MA, Quigley MF, Gostick E, Price DA, Humphreys IR. IL-10 restricts memory T cell inflation during cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:3583–3592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminskyy V, Zhivotovsky B. To kill or be killed: how viruses interact with the cell death machinery. J Intern Med. 2010;267:473–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern ER. Pivotal role of animal models in the development of new therapies for cytomegalovirus infections. Antiviral research. 2006;71:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe DM, Cliffe A. Chromatin control of herpes simplex virus lytic and latent infection. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Xu J, Mocarski ES. Human cytomegalovirus latent gene expression in granulocyte-macrophage progenitors in culture and in seropositive individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11137–11142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korioth F, Maul GG, Plachter B, Stamminger T, Frey J. The nuclear domain 10 (ND10) is disrupted by the human cytomegalovirus gene product IE1. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229:155–158. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn DE, Beall CJ, Kolattukudy PE. The cytomegalovirus US28 protein binds multiple CC chemokines with high affinity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211:325–330. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung CP, Meckes DG, Jr, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 activates EGFR, STAT3, and ERK through effects on PKCdelta. J Virol. 2011;85:4399–4408. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01703-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz SK, Rapp M, Steffens HP, Grzimek NK, Schmalz S, Reddehase MJ. Focal transcriptional activity of murine cytomegalovirus during latency in the lungs. J Virol. 1999;73:482–494. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.482-494.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DL, Thompson HW, Bloom DC. The polycomb group protein Bmi1 binds to the herpes simplex virus 1 latent genome and maintains repressive histone marks during latency. J Virol. 2009;83:8173–8181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00686-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMarca HL, Nelson AB, Scandurro AB, Whitley GS, Morris CA. Human cytomegalovirus-induced inhibition of cytotrophoblast invasion in a first trimester extravillous cytotrophoblast cell line. Placenta. 2006;27:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landini MP, Lazzarotto T, Xu J, Geballe AP, Mocarski ES. Humoral immune response to proteins of human cytomegalovirus latency-associated transcripts. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6:100–108. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le VT, Trilling M, Hengel H. The Cytomegaloviral Protein pUL138 Acts as Potentiator of TNF Receptor 1 Surface Density to Enhance ULb′-encoded modulation of TNF-{alpha} Signaling. J Virol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/JVI.06005-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Zhu J, Xie Z, Liao G, Liu J, Chen MR, Hu S, Woodard C, Lin J, Taverna SD, et al. Conserved herpesvirus kinases target the DNA damage response pathway and TIP60 histone acetyltransferase to promote virus replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Yuan J, Wu AW, McGonagill PW, Galle CS, Meier JL. Phorbol ester-induced human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early (MIE) enhancer activation through PKC-delta, CREB, and NF-kappaB desilences MIE gene expression in quiescently infected human pluripotent NTera2 cells. J Virol. 2010;84:8495–8508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00416-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashchuk V, McFarlane S, Everett RD, Preston CM. Human cytomegalovirus protein pp71 displaces the chromatin-associated factor ATRX from nuclear domain 10 at early stages of infection. J Virol. 2008;82:12543–12554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01215-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EE, Bierle CJ, Brune W, Geballe AP. Essential role for either TRS1 or IRS1 in human cytomegalovirus replication. J Virol. 2009;83:4112–4120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02489-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul GG. Nuclear domain 10, the site of DNA virus transcription and replication. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 1998;20:660–667. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<660::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul GG. Initiation of cytomegalovirus infection at ND10. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:117–132. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier JL, Stinski MF. Major Immediate Early Enhancer and its Gene Products. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2006. pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C, Grey F, Kreklywich CN, Andoh TF, Tirabassi RS, Orloff SL, Streblow DN. Cytomegalovirus microRNA expression is tissue specific and is associated with persistence. J Virol. 2011;85:378–389. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01900-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C, Wagner JA, Gruska I, Vetter B, Wiebusch L, Hagemeier C. The latency-associated UL138 gene product of human cytomegalovirus sensitizes cells to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) signaling by upregulating TNF-alpha receptor 1 cell surface expression. J Virol. 2011;85:11409–11421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05028-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Vanicek J, Robins H, Shenk T, Levine AJ. Suppression of immediate-early viral gene expression by herpesvirus-coded microRNAs: implications for latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5453–5458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711910105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JC, Fischle W, Verdin E, Sinclair JH. Control of cytomegalovirus lytic gene expression by histone acetylation. Embo J. 2002;21:1112–1120. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmani D, Lankry D, Wolf DG, Mandelboim O. The human cytomegalovirus microRNA miR-UL112 acts synergistically with a cellular microRNA to escape immune elimination. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:806–813. doi: 10.1038/ni.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevels M, Nitzsche A, Paulus C. How to control an infectious bead string: nucleosome-based regulation and targeting of herpesvirus chromatin. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:154–180. doi: 10.1002/rmv.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzsche A, Paulus C, Nevels M. Temporal dynamics of cytomegalovirus chromatin assembly in productively infected human cells. J Virol. 2008;82:11167–11180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01218-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannuti CS, Vilas Boas LS, Angelo MJ, Amato Neto V, Levi GC, de Mendonca JS, de Godoy CV. Cytomegalovirus mononucleosis in children and adults: differences in clinical presentation. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 1985;17:153–156. doi: 10.3109/inf.1985.17.issue-2.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus C, Nitzsche A, Nevels M. Chromatinisation of herpesvirus genomes. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:34–50. doi: 10.1002/rmv.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrucelli A, Rak M, Grainger L, Goodrum F. Characterization of a Novel Golgi-localized Latency Determinant Encoded by Human Cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2009;83:5615–5629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01989-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole E, McGregor Dallas SR, Colston J, Joseph RS, Sinclair J. Virally induced changes in cellular microRNAs maintain latency of human cytomegalovirus in CD34 progenitors. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:1539–1549. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.031377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers C, DeFilippis V, Malouli D, Fruh K. Cytomegalovirus immune evasion. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:333–359. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers C, Fruh K. Rhesus CMV: an emerging animal model for human CMV. Medical microbiology and immunology. 2008;197:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s00430-007-0073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston CM, Nicholl MJ. Role of the cellular protein hDaxx in human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1113–1121. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph-Habecker JR, Rahill B, Torok-Storb B, Vieira J, Kolattukudy PE, Rovin BH, Sedmak DD. The expression of the cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor homolog US28 sequesters biologically active CC chemokines and alters IL-8 production. Cytokine. 2002;19:37–46. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddehase MJ, Podlech J, Grzimek NK. Mouse models of cytomegalovirus latency: overview. J Clin Virol. 2002;25(Suppl 2):S23–36. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves M, Murphy J, Greaves R, Fairley J, Brehm A, Sinclair J. Autorepression of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter/enhancer at late times of infection is mediated by the recruitment of chromatin remodeling enzymes by IE86. J Virol. 2006;80:9998–10009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01297-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves M, Woodhall D, Compton T, Sinclair J. Human cytomegalovirus IE72 protein interacts with the transcriptional repressor hDaxx to regulate LUNA gene expression during lytic infection. J Virol. 2010;84:7185–7194. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02231-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves MB, Breidenstein A, Compton T. Human cytomegalovirus activation of ERK and myeloid cell leukemia-1 protein correlates with survival of latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114966108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves MB, Compton T. Inhibition of inflammatory interleukin-6 activity via extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling antagonizes human cytomegalovirus reactivation from dendritic cells. J Virol. 2011;85:12750–12758. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05878-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves MB, MacAry PA, Lehner PJ, Sissons JG, Sinclair JH. Latency, chromatin remodeling, and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus in the dendritic cells of healthy carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4140–4145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408994102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves MB, Sinclair JH. Analysis of latent viral gene expression in natural and experimental latency models of human cytomegalovirus and its correlation with histone modifications at a latent promoter. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:599–604. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsma JM, Savaryn JP, Faust K, Sato H, Halligan BD, Terhune SS. Antiviral inhibition targeting the HCMV kinase pUL97 requires pUL27-dependent degradation of Tip60 acetyltransferase and cell-cycle arrest. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. Inactivating a cellular intrinsic immune defense mediated by Daxx is the mechanism through which the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein stimulates viral immediate-early gene expression. J Virol. 2006;80:3863–3871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3863-3871.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression is silenced by the Daxx-mediated intrinsic immune defense when model latent infections are established in vitro. J Virol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00827-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffert RT, Penkert RR, Kalejta RF. Cellular and viral control over the initial events of human cytomegalovirus experimental latency in CD34+ cells. J Virol. 2010;84:5594–5604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00348-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez V, Spector DH. Subversion of cell cycle regulatory pathways. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:243–262. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Shirata N, Murata T, Nakasu S, Kudoh A, Iwahori S, Nakayama S, Chiba S, Isomura H, Kanda T, et al. Transient increases in p53-responsible gene expression at early stages of Epstein-Barr virus productive replication. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:807–814. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR. Nonprimate models of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection: gaining insight into pathogenesis and prevention of disease in newborns. ILAR J. 2006;47:65–72. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slinger E, Maussang D, Schreiber A, Siderius M, Rahbar A, Fraile-Ramos A, Lira SA, Soderberg-Naucler C, Smit MJ. HCMV-encoded chemokine receptor US28 mediates proliferative signaling through the IL-6-STAT3 axis. Science signaling. 2010;3:ra58. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MS, Goldman DC, Bailey AS, Pfaffle DL, Kreklywich CN, Spencer DB, Othieno FA, Streblow DN, Garcia JV, Fleming WH, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor reactivates human cytomegalovirus in a latently infected humanized mouse model. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck SH, Ganem D. Viral latency and its regulation: lessons from the gamma-herpesviruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagno S, Reynolds DW, Pass RF, Alford CA. Breast milk and the risk of cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1073–1076. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005083021908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern-Ginossar N, Elefant N, Zimmermann A, Wolf DG, Saleh N, Biton M, Horwitz E, Prokocimer Z, Prichard M, Hahn G, et al. Host immune system gene targeting by a viral miRNA. Science. 2007;317:376–381. doi: 10.1126/science.1140956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern-Ginossar N, Saleh N, Goldberg MD, Prichard M, Wolf DG, Mandelboim O. Analysis of human cytomegalovirus-encoded microRNA activity during infection. J Virol. 2009;83:10684–10693. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01292-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streblow DN, Dumortier J, Moses AV, Orloff SL, Nelson JA. Mechanisms of cytomegalovirus-accelerated vascular disease: induction of paracrine factors that promote angiogenesis and wound healing. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:397–415. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streblow DN, van Cleef KW, Kreklywich CN, Meyer C, Smith P, Defilippis V, Grey F, Fruh K, Searles R, Bruggeman C, et al. Rat cytomegalovirus gene expression in cardiac allograft recipients is tissue specific and does not parallel the profiles detected in vitro. J Virol. 2007;81:3816–3826. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02425-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs M, Banati F, Koroknai A, Segesdi J, Salamon D, Wolf H, Niller HH, Minarovits J. Epigenetic regulation of latent Epstein-Barr virus promoters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JC, Avdic S, Cao JZ, Mocarski ES, White KL, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. Inhibition of 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase expression and function by the human cytomegalovirus ORF94 gene product. J Virol. 2011;85:5696–5700. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02463-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalai N, Adler M, Scherer M, Riedl Y, Stamminger T. Evidence for a dual antiviral role of the major nuclear domain 10 component Sp100 during the immediate-early and late phases of the human cytomegalovirus replication cycle. J Virol. 2011;85:9447–9458. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00870-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalai N, Papior P, Rechter S, Leis M, Stamminger T. Evidence for a role of the cellular ND10 protein PML in mediating intrinsic immunity against human cytomegalovirus infections. J Virol. 2006;80:8006–8018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00743-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalai N, Papior P, Rechter S, Stamminger T. Nuclear domain 10 components promyelocytic leukemia protein and hDaxx independently contribute to an intrinsic antiviral defense against human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:126–137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01685-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalai N, Stamminger T. New insights into the role of the subnuclear structure ND10 for viral infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:2207–2221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalai N, Stamminger T. Intrinsic cellular defense mechanisms targeting human cytomegalovirus. Virus Res. 2011;157:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth Z, Maglinte DT, Lee SH, Lee HR, Wong LY, Brulois KF, Lee S, Buckley JD, Laird PW, Marquez VE, et al. Epigenetic analysis of KSHV latent and lytic genomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001013. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umashankar M, Petrucelli A, Cicchini L, Caposio P, Kreklywich CN, Rak M, Bughio F, Goldman DC, Hamlin KL, Nelson JA, et al. A novel human cytomegalovirus locus modulates cell type-specific outcomes of infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002444. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbach JL, Kramer MF, Jurak I, Karnowski HW, Coen DM, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008;454:780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vomaske J, Melnychuk RM, Smith PP, Powell J, Hall L, DeFilippis V, Fruh K, Smit M, Schlaepfer DD, Nelson JA, et al. Differential ligand binding to a human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor determines cell type-specific motility. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000304. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QY, Zhou C, Johnson KE, Colgrove RC, Coen DM, Knipe DM. Herpesviral latency-associated transcript gene promotes assembly of heterochromatin on viral lytic-gene promoters in latent infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16055–16059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505850102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Huong SM, Chiu ML, Raab-Traub N, Huang ES. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a cellular receptor for human cytomegalovirus. Nature. 2003;424:456–461. doi: 10.1038/nature01818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KL, Slobedman B, Mocarski ES. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated protein pORF94 is dispensable for productive and latent infection. J Virol. 2000;74:9333–9337. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.9333-9337.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills M, Akbar A, Beswick M, Bosch JA, Caruso C, Colonna-Romano G, Dutta A, Franceschi C, Fulop T, Gkrania-Klotsas E, et al. Report from the Second Cytomegalovirus and Immunosenescence Workshop. Immun Ageing. 2011;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhall DL, Groves IJ, Reeves MB, Wilkinson G, Sinclair JH. Human Daxx-mediated repression of human cytomegalovirus gene expression correlates with a repressive chromatin structure around the major immediate early promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37652–37660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Silva MC, Shenk T. Functional map of human cytomegalovirus AD169 defined by global mutational analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12396–12401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635160100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Liu X, Wu AW, McGonagill PW, Keller MJ, Galle CS, Meier JL. Breaking human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early gene silence by vasoactive intestinal peptide stimulation of the protein kinase A-CREB-TORC2 signaling cascade in human pluripotent embryonal NTera2 cells. J Virol. 2009;83:6391–6403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00061-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurochko AD. Human cytomegalovirus modulation of signal transduction. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:205–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanghellini F, Boppana SB, Emery VC, Griffiths PD, Pass RF. Asymptomatic primary cytomegalovirus infection: virologic and immunologic features. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:702–707. doi: 10.1086/314939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zydek M, Hagemeier C, Wiebusch L. Cyclin-dependent kinase activity controls the onset of the HCMV lytic cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001096. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zydek M, Uecker R, Tavalai N, Stamminger T, Hagemeier C, Wiebusch L. General blockade of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early mRNA expression in the S/G2 phase by a nuclear, Daxx- and PML-independent mechanism. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2757–2769. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.