Abstract

Four Large Münsterländer cross-bred dogs affected with black hair follicular dysplasia (BHFD) and one unaffected control littermate were observed, and skin was sampled weekly over the first 19 weeks of life. Affected dogs were born with silvery grey hair, a consequence of melanin clumping in the hair shafts. Hair bulb melanocytes were densely pigmented, and contained abundant stage IV melanosomes but adjacent matrix keratinocytes lacked melanosomes. Melanin clumping was not prominent in epidermal melanocytes in the haired skin but occurred in the foot pads. Follicular changes progressed from bulbar clumping, clumping in the isthmus/ infundibulum and finally to dysplastic hair shafts. Alopecia developed progressively in pigmented areas.

Silver-grey hair, melanin clumping, accumulation of stage IV melanosomes within melanocytes and insufficient melanin transfer to adjacent keratinocytes are also classic features of human Griscelli syndrome. The underlying cause in Griscelli syndrome is a defect of melanocytic intracellular transport proteins leading to inadequate and disorganized melanosome transfer to keratinocytes with resultant melanin clumping. In view of the correlation in the phenotype, histology and ultrastructure between both disorders, a defect in intracellular melanosome transport is postulated as the pathogenic mechanism in BHFD.

Introduction

Canine black hair follicular dysplasia (BHFD) is a rare disorder confined to black coat regions affecting bicolor or tricolor animals within the first few weeks of life. It occurs in mongrels and several breeds, including Salukis, Jack Russell terriers and Large Münsterländers.1–9 Lesions are characterized by dull, dry, lusterless hair, hair fracture, hypotrichosis and scaliness. An autosomal recessive mode of inheritance has been determined for the Large Münsterländer.4 Histopathology is characterized by accumulation of melanin clumps within hair shafts, follicular lumina, root sheaths and hair bulbs. Hair shafts are irregular, bulging or replaced by keratinous debris.2 Characteristic features of macromelanosomes such as increased size, outer trilaminar membrane and vesiculoglobular bodies10 are not detected, thus the more neutral term ‘clumped melanin’ is preferred.

In recent years, understanding of the physiological transport of melanosomes from post-Golgi compartments to the periphery of melanocytes has increased. Within melanocytes, mature stage IV melanosomes are transported in a centrifugal manner from the Golgi apparatus to the cell processes by several transport proteins including myosin Va, RAB27a and melanophilin.11–15

In human Griscelli syndrome (GS) parts of this transport machinery are disrupted, leading to pigmentary dilution of the skin, a silver-grey sheen of the hair and the presence of large clumps of pigment in the hair shafts.16,17 In 1978, Griscelli initially described two patients with partial albinism and immunodeficiency. This syndrome was later termed type 1 GS and an underlying defect of the myosin Va gene (MYO5A) was established.18 Type 2 GS (GS2) is characterized by skin lesions and concurrent uncontrolled T lymphocyte and macrophage activation and haemophagocytic syndrome, and a defect in the RAB27a gene was determined to be the cause.19 A mutation in the melanophilin gene (MLPH) was implicated in a third type of GS, which is restricted to cutaneous lesions.17 Regardless which of the transport proteins are affected, all types of GS share the same melanocyte morphology which results from disrupted melanosome transport to the periphery.16–20 As a result, epidermal melanocytes are hyperpigmented and melanosomes have abnormal perinuclear location with limited translocation to the dentrites. Adjacent keratinocytes are poorly pigmented and hair shafts contain clumped melanin.16,20 Corresponding dilute, ashen and leaden mutations in mice are well characterized13–15,21–23 and there is recent evidence of MLPH gene mutation in dogs with BHFD or colour dilution.24

In the light of this molecular evidence linking canine BHFD and human GS, the objective was to characterize the clinical, histological and particularly the electron microscopic sequence of events in BHFD in relation to GS.

Materials and methods

An 8-week-old, intact male Large Münsterländer with black hair follicular dysplasia was used to establish a breeding colony. The propositus was initially mated with a normal female beagle producing six phenotypically normal females and one phenotypically normal male. To produce affected dogs, the propositus was then mated with one of the female offspring resulting in four affected pups (one female and three males) and four phenotypically normal pups (one female and three males). All animals were cared for according to the principles outlined in the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals25 and the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals (CIOMS).26 The four affected (BL51, BL53, BL54 and BL55) and the phenotypically normal female (BL52) Large Münsterländer crosses were observed over the first 19 weeks of life, and the progress of the disorder was documented weekly. Skin biopsies (6 mm in diameter) were collected under local anaesthesia from dark-haired areas on the trunk alternating between the right and the left side. Eighty-three samples were collected, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, sagittally sectioned, routinely processed for histopathological evaluation and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). To clarify morphology in sections obscured by large amounts of clumped melanin, additional sections were bleached prior to staining by immersion in 0.25% potassium permanganate (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature, then rinsed in aqua bidest, and immersed in 1% oxalic acid (Fisher Scientific) for 5 min.

Semiquantitative scores were assigned to each of three categories within every skin sample, namely bulbar changes, isthmic/infundibular melanin clumping and dysplasia of hair shafts.

1 Bulbar changes were defined as excessive (as compared to the normal control dog) accumulation of intracellular melanin in bulbar matrix cells or extracellular accumulation of melanin clumps with or without the separation of bulbar matrix cells.

2 Isthmic/infundibular clumping was defined as accumulation of clumped melanin within the follicle lumen at the level of the infundibulum or isthmus.

3 Dysplastic hair shafts were defined as hair shafts lacking a morphologically distinct medulla and cortex or luminal accumulation of keratinous debris with distension, thinning or bulging of the outer root sheath.

Because the number of hair follicles per skin sample varied with skin location and age of the animal, a ratio of affected to unaffected hair follicles was used to quantify the severity of the changes. Thus in each skin sample, the three categories were given scores of 0 (absent or mild) for involvement of less than 10% of all hair follicles; 1 (moderate) for involvement of 10–50% of all hair follicles; and 2 (severe) for involvement of more than 50% of all hair follicles. To create a total score for each skin sample, the individual category scores were summated (0–1: absent to mild; 2–4: moderate; 5–6: severe).

At the age of 10 months, one affected (BL53) and one unaffected dog (BL52) each had a 6-mm skin biopsy taken under local anaesthesia from a dark-haired region on the dorsum. The samples were immediately fixed for 3.5 h at 4 °C in a 1:1 mixture of 2.5% glutaraldehyde [in 0.1 mol L−1 Na-cacodylate buffer, pH = 7.2] and 1% formaldehyde [in 0.1 mol L−1 Na-cacodylate buffer, pH = 7.2]. They were stored until further processing at room temperature. Specimens were postfixed with 2% cacodylate-buffered OsO4, dehydrated with graded ethanol solutions and embedded in Epon® (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA, USA). Semi-thin sections (0.3 μm) were collected on glass slides and stained with 1% toluidine blue. Thin sections (170 nm) were also cut and stained with an alcoholic solution of uranyl acetate, followed by a solution of bismuth subnitrite. Sections were examined using a JEOL JEM1010 (JEOL, Peabody, MA) electron microscope and photographed digitally.

Results

Clinical data

At birth, the affected dogs had a silver-grey and white pelage and were easily distinguished from the normal black-and white-haired littermate (Fig. 1). Over the following 3 weeks, the grey areas darkened, almost approaching black. At 1 month, the dark grey hair was slightly dull with no gross evidence of hair loss but by 8–12 weeks, became brittle and less dense; hair breakage occurred. The undercoat was sparse and never completely developed. At 14–16 weeks, all grey areas had incomplete but diffuse alopecia with small, unevenly scattered brittle and fractured hairs (Fig. 2). From 8 to 12 months, some new hair growth was evident in alopecic areas with sparse dark grey to black hair and no undercoat. White-haired areas remained normal in both the affected and the control dogs.

Figure 1.

Four dogs affected with BHFD and one control littermate (in the middle) at the age of 1 week. Note the silver-grey instead of black colour in dark-haired patches.

Figure 2.

Dog affected with BHFD (left) and unaffected control littermate (right) at the age of 17 weeks. Note the alopecia and grey-silvery hair coat (arrow).

Histopathology

Normal control dog

The control pup (BL52) only rarely exhibited small clumps of melanin in hair shafts or the external root sheath and never luminal clumping. Pigment clumping was not observed in the hair follicle matrix; there were no dysplastic hair shafts. Melanocytes were only infrequently (mean of one per sample) identifiable in the epidermis and had brown intracytoplasmic evenly distributed melanin and sometimes visible cytoplasmic processes. Adjacent keratinocytes contained moderate amounts of melanin. This overall picture was also obtained in the other three phenotypically normal animals, which were examined while in use in other studies.

Affected dogs

At week 1, affected dogs had clumped melanin in the cortex and the medulla of all hair shafts, the degree of which did not change over the course of the disease.

In two pups starting at week 15 (BL51) and week 16 (BL53), respectively, the number of observable epidermal melanin-filled melanocytes increased slightly (mean of 4 per sample) and remained elevated until the end of the study. In all affected dogs, epidermal melanocytes were heavily pigmented with perinuclear accumulation of pigment. Cellular processes were rarely identifiable. The surrounding keratinocytes were sparsely pigmented.

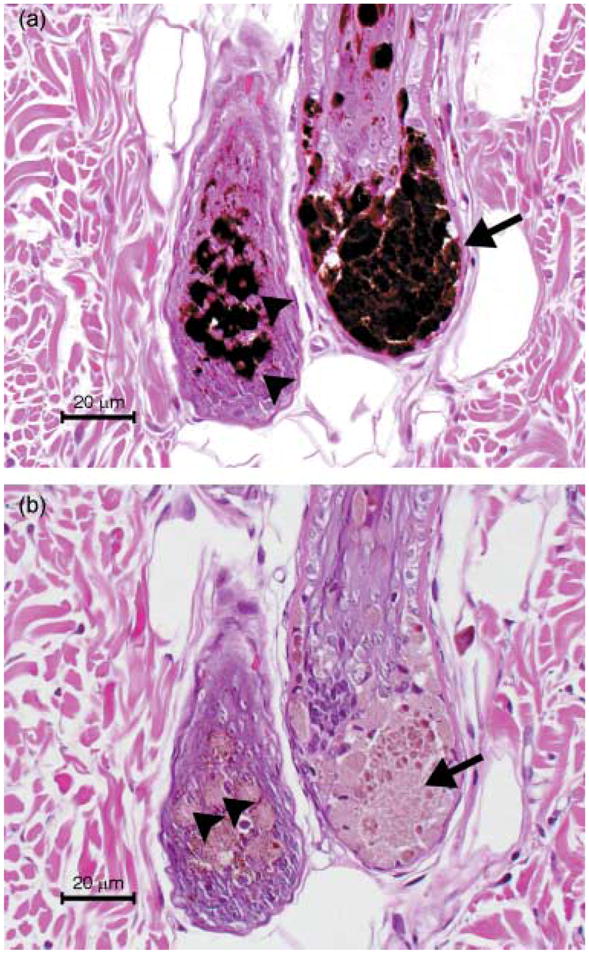

Three of the affected dogs (BL51, BL53 and BL54) had qualitatively and sequentially similar hair follicle changes (Table 1). Bulbar changes were the first to be observed. Melanin formed large clumps that separated bulbar matrix cells and distorted the hair bulb architecture (Fig. 3a,b); intracellular clumps were most prominent in the bulbar matrix cells adjacent to the dermal papilla. Initial lesions were minimal and started by week 2 (BL51) or week 3 (BL53 and BL54) and increased over the course of the study.

Table 1.

Lesion scores for four dogs affected with BHFD over the first 19-weeks of life

| Week | BL51 | BL53 | BL54 | BL55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,0,0 0 | 0,0,0 0 | 0,0,0 0 | 2,1,0 3 |

| 2 | 1,1,1 3 | 0,0,0 0 | 0,0,0 0 | 2,2,2 6 |

| 3 | 1,1,1 3 | 1,1,0 2 | 1,0,0 1 | 1,2,2 5 |

| 4 | 2,1,1 4 | 1,1,0 2 | 1,0,0 1 | 2,2,2 6 |

| 5 | 1,1,0 2 | 1,1,1 3 | 1,0,0 1 | 1,2,2 5 |

| 6 | 0,1,1 2 | 1,1,0 2 | 1,1,1 3 | * |

| 7 | 1,1,2 4 | 0,1,1 2 | 1,1,1 3 | 1,2,2 5 |

| 8 | 1,1,2 4 | 1,1,0 2 | 1,1,1 3 | 1,2,2 5 |

| 9 | 2,1,2 5 | 1,1,2 4 | 1,1,1 3 | |

| 10 | 1,2,1 4 | 1,1,1 3 | 2,1,1 4 | |

| 11 | 0,2,2 4 | 1,2,2 5 | 2,1,2 5 | |

| 12 | 1,1,2 4 | 2,1,2 5 | 1,1,2 4 | |

| 13 | 2,1,1 4 | 1,1,2 4 | 1,2,2 5 | |

| 14 | 2,1,2 5 | 1,1,2 4 | 2,2,2 6 | |

| 15 | 2,1,1 4 | 2,1,2 5 | 1,2,2 5 | |

| 16 | 1,2,1 4 | 1,1,2 4 | 2,2,1 5 | |

| 17 | 2,2,2 6 | 2,2,2 6 | 1,1,1 3 | |

| 18 | 1,2,2 5 | 2,1,2 5 | 2,2,2 6 | |

| 19 | 1,1,2 4 | 2,1,1 4 | 2,2,1 5 |

no biopsy taken.

Columns 2–4 show the scores (0: absent to mild; 1: moderate; 2: severe) for each skin sample obtained from animals BL51, BL53, BL54 and BL55 over the 19-week collection period (only 8 weeks in animal BL54). Scores for each skin sample include three categories (bulbar changes, isthmic/infundibular clumping and dysplastic hair shafts) followed by the total score (in bold). These results show a progressive increase in the overall severity of the condition with time.

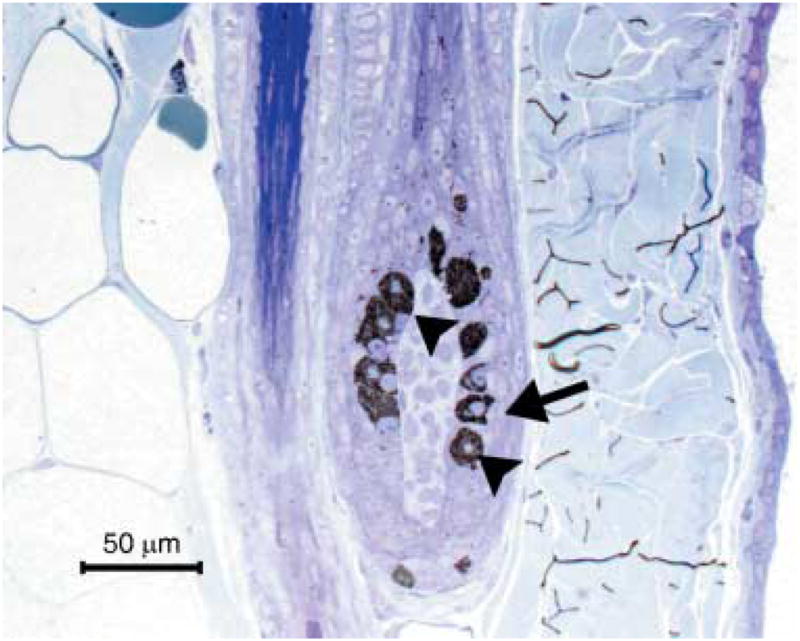

Figure 3.

Two hair bulbs of a dog with BHFD. Note the melanin clumping within basal melanocytes (arrow heads) and accumulation of extracellular melanin (arrow). H&E (a) and potassium permanganate bleached section (b).

Isthmic/infundibular clumping started simultaneously (BL51 and BL53) with or shortly after the bulbar changes (BL54). The areas most affected were the hair infundibulum and the transition between infundibulum and isthmus. Clumping was prominent within the lumen and generally associated with keratinaceous debris. The degree of clumping increased over the course of the study. Between week 7 and the end of the study both anagen and telogen hairs were present consistently; no association between anagen/telogen ratio and degree of clumping was found.

Dysplastic hair shafts occurred with (BL51 and BL54) or followed isthmic/infundibular clumping (BL53). The proportion of dysplastic hair shafts gradually increased, but nondysplastic hair shafts were present throughout the study in all samples.

Total scores gradually increased over the course of the study (Table 1). By week 6, all dogs had moderate lesions and by week 11, they displayed severe lesions in at least one sample. Between week 6 and the end of the study, all animals had consistently moderate or severe lesions.

Dermal macrophages with intracytoplasmic melanin were few and scattered around the hair bulbs and the inferior portion of the hair follicles. Subjectively, two animals had a subtle increase in number of melanophages from week 14 (BL54) and week 15 (BL51) onwards.

One affected male pup (BL55) already displayed moderate changes by week 1 and severe changes at week 2 and was euthanized at week 8 for humane reasons; failure to thrive and poor nutritional condition. It was submitted for post-mortem examination. Despite the early age of onset and the greater severity of the lesions, the sequence of events was the same as that seen in the three other affected dogs (Table 1).

Post-mortem findings

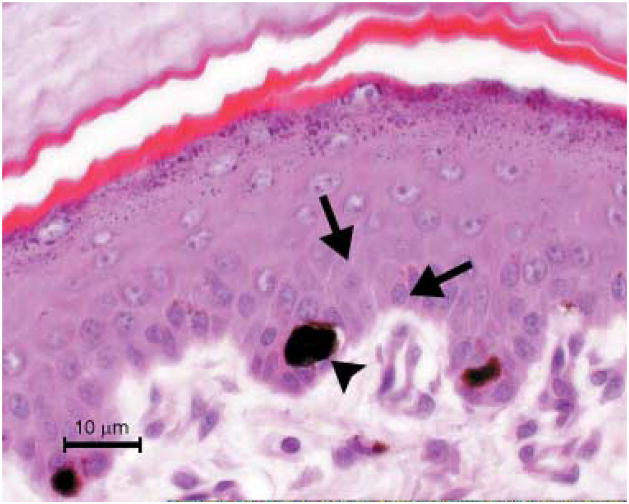

No gross or histological lesions to explain the failure to thrive were found. White-haired areas were normal. At the transition to dark-haired areas, there was an abrupt change to the severely altered skin condition. Pigmented epidermis of the footpads contained unevenly distributed, round melanocytes filled with abundant, often clumped melanin (Fig. 4). Melanocytic processes were not observed. Surrounding keratinocytes contained few or no melanosomes.

Figure 4.

Accessory foot pad of a dog with BHFD. Note the rounded appearance of the melanocyte (arrow head) and lack of melanin in the adjacent keratinocytes (arrows); H&E.

Electron microscopy

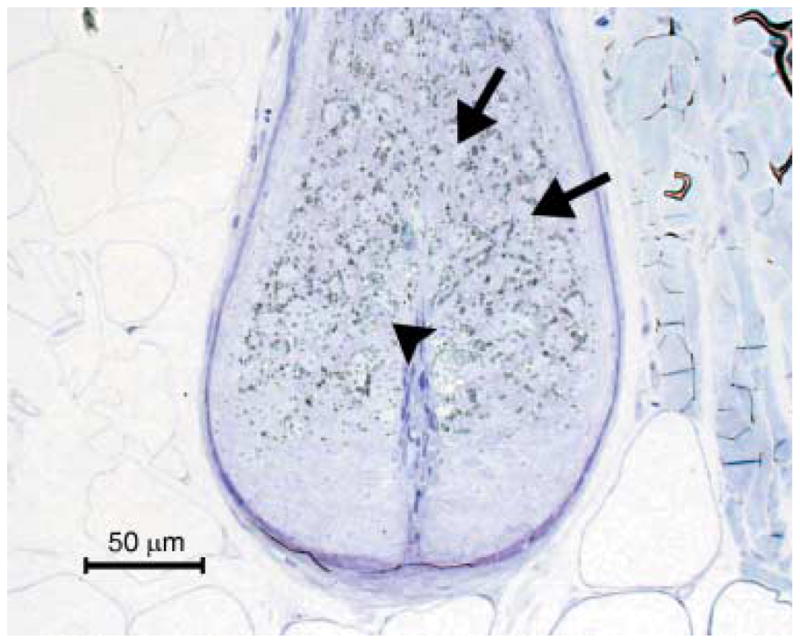

In the unaffected control pup (BL 52), bulbar melanocytes had centrally located nuclei, and melanosomes were evenly and loosely distributed throughout the cytoplasm. The majority of melanosomes were at stage IV; fewer at stage III and stage II. Stage I melanosomes were not identified. Adjacent matrix keratinocytes contained evenly distributed stage IV melanosomes (Figs 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Hair bulb of the unaffected control littermate. Note the even distribution of melanin within melanocytes (arrow head) and matrix keratinocytes (arrows). Toluidine blue, semi-thin section.

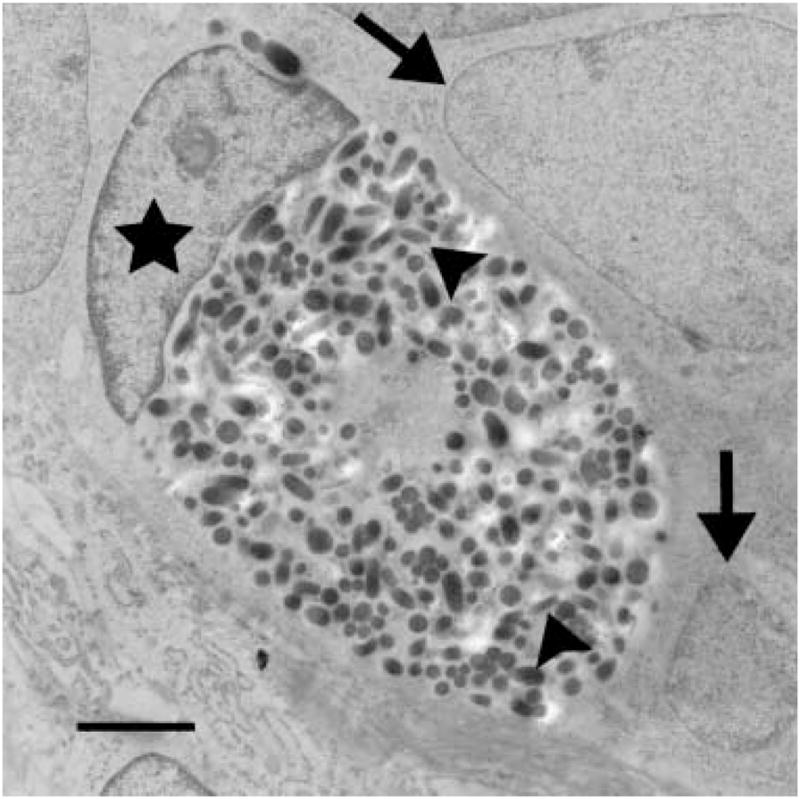

Figure 6.

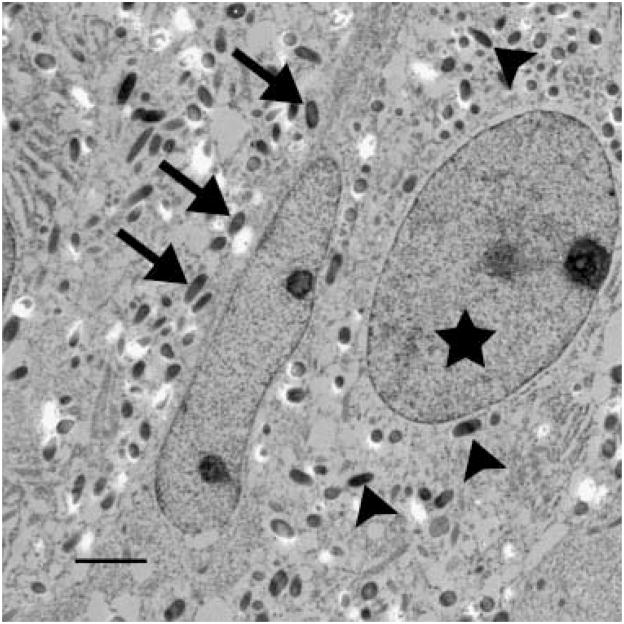

Melanocyte and adjacent matrix keratinocytes in the hair bulb of the unaffected control littermate. Note the even distribution of melanosomes within the melanocyte (arrow heads) and adjacent keratinocytes (arrows). The nucleus (asterisk) is centrally located within the melanocyte. Ultrathin section; ×5000; bar = 2 μm.

In the affected animal (BL 53), melanocyte nuclei were displaced eccentrically and indented. The cytoplasm was tightly packed with abundant stage IV melanosomes. Few stage II and stage III melanosomes were present and these were located close to the nucleus. Stage I melanosomes could not be identified. Melanosomes were of equal size as in the control animal and did not fuse or form macromelanosomes. Adjacent matrix keratinocytes were devoid of melanosomes (Figs 7 and 8).

Figure 7.

Hair bulb of a dog with BHFD. Note melanocytes (arrow head) filled with abundant melanin and lack of melanin in adjacent matrix keratinocytes (arrow). Toluidine blue, semithin section.

Figure 8.

Melanocyte and adjacent matrix keratinocytes in the hair bulb of a dog with BHFD. Note within the melanocyte the large number of stage IV melanosomes (arrow heads) and the eccentrically displaced nucleus (asterisk). Adjacent matrix keratinocytes (arrows) lack melanosomes. Ultrathin section; ×10 000; bar = 2 μm.

Discussion

The histological and ultrastructural lesions of canine BHFD share features with GS in man.16,17 A defect of melanosome transport within melanocytes with disruption of the pigmentary unit is therefore proposed as an integral part of the pathogenic mechanism in BHFD.

First, affected Large Münsterländer crosses had comparable heavily pigmented melanocytes. The skin of these dogs is normally light grey and it is therefore not surprising that only a few pigmented melanocytes were observable in the epidermis of haired skin. In contrast, the epidermal melanocytes of the heavily pigmented footpads had severe intracellular melanin clumping, a rounded appearance and few identifiable processes. The degree of melanin clumping is therefore linked to the activity of the melanocytes, leading to more clumping in naturally more pigmented locations. Adjacent keratinocytes contained little pigment, suggestive of inadequate transfer of melanin.

Second, the ultrastructure of melanocytes in the hair bulbs supports a similarity to GS.16,20,27 Affected dogs had melanocytes filled with densely packed melanosomes and nuclei frequently displaced to the periphery of the cells; the adjacent matrix keratinocytes lacked melanosomes.

Finally, an important feature in human GS is hair shaft clumping of melanin leading to the clinical appearance of silvery-grey hair.16,20 The hair of Large Münsterländer crosses contained cortical and medullary melanin clumping leading to the clinical appearance of a dilute phenotype. Based on these results, BHFD resembles GS in epidermal melanin clumping, melanocyte morphology, ultrastructure and accumulation of clumped melanin in hair shafts.

However, alopecia, dysplastic hair shafts and accumulation of clumped melanin within hair follicle lumina which are important features of BHFD have not been described in GS.16–19,20,27 The reason for this difference between GS and BHFD is unknown. However, following BHFD disease progression over the first 19 weeks of life has provided an interesting insight into the pathogenesis. Despite the presence of melanin clumping in hair shafts from week 1, initial follicular lesions were minimal, and dysplastic hairs were not present. Instead, the development of dysplastic hair shafts was tightly linked to initial bulbar changes. Hair bulb architecture was distorted by intracellular melanin accumulation in bulbar melanocytes and large pigment clumps separating bulbar matrix cells. This anatomical disruption of the germinal centre of the hair shaft could thus be an additional factor contributing to the development of the dysplastic hair shafts, characteristic of BHFD. Previously, cuticular defects, caused by the melanin clumping, has been suggested as the cause of dysplastic hair shafts.2

Nevertheless, the relation between the accumulation of melanosomes, the formation of melanin clumps and the occurrence of dysplastic hair shafts is still insufficiently explained. Future studies should therefore target the events that occur during the transfer of melanosomes to adjacent keratinocytes. Even in healthy humans, this process has not been fully elucidated.13–15 It probably involves multiple mechanisms including the engulfment of melanocytic dendrites by keratinocytes, the secretion of melanosomes into the extracellular space, injection of melanosomes by the melanocyte into keratinocytes and transfer via a pore spanning both cell types.13 Even less is known about the mechanisms in BHFD. Possible mechanisms include melanocytic degeneration with release of melanosomes and subsequent phagocytosis by adjacent keratinocytes. Alternatively, melanosomes could be discontinuously transferred from viable melanocytes to adjacent keratinocytes by disorganized cytokinesis.

It remains to be determined if the present findings fit all cases of BHFD and colour dilution alopecia (CDA) or are to be found exclusively in Large Münsterländer dogs. It has been speculated that BHFD and CDA are the same entity, as both share histological findings and because some dogs with BHFD are born with grey and white rather than black and white coats.4,28 The early age of onset in BHFD, however, differentiates the disease clinically. Epidermal melanin clumping that occurs in CDA29–32 was not originally described in BHFD1,6 and was considered by some to be a discriminating feature.5 However, epidermal melanin clumping has been found more recently in BHFD2,7 and also was observed in this study. Moreover, recent studies have suggested the same molecular defect for both diseases,24 supporting the premise that CDA and BHFD merely represent different manifestations of the same disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Neelima Shah, Biomedical Imaging Core of the University of Pennsylvania for specimen preparation and valuable assistance with ultrastructural interpretation, and to Patty O’Donnell and the students of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine for excellent BHDF colony husbandry. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (RR02512).

References

- 1.Selmanowitz VJ, Kramer KM, Orentreich N. Canine hereditary black hair follicular dysplasia. Journal of Heredity. 1972;63:43–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a108220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hargis AM, Brignac MM, Kareem Al-Bagdadi FA, et al. Black hair follicular dysplasia in black and white Saluki dogs: differentiation from color mutant alopecia in the Doberman Pinscher by microscopic examination of hairs. Veterinary Dermatology. 1991;2:69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knottenbelt CM, Knottenbelt MK. Black hair follicular dysplasia in a tricolour Jack Russell terrier. Veterinary Record. 1996;138:475–6. doi: 10.1136/vr.138.19.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmutz SM, Moker JS, Clark EG, et al. Black hair follicular dysplasia, an autosomal recessive condition in dogs. Canadian Veterinary Journal. 1998;39:644–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delmage DA. Black hair follicular dysplasia. Veterinary Record. 1995;137:79–80. doi: 10.1136/vr.136.3.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selmanowitz VJ, Markofsky J, Orentreich N. Black-hair follicular dysplasia in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1977;15:1079–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlotti DN. Canine hereditary black hair follicular dysplasia and colour mutant alopecia: clinical and histopathological aspects. In: von Tscharner C, Halliwell REW, editors. Advances in Veterinary Dermatology. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Bailliere Tindall; 1990. pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis CL. Black hair follicular dysplasia in UK bred Salukis. Veterinary Record. 1995;137:294–5. doi: 10.1136/vr.137.12.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn KA, Russell M, Boness JM. Black hair follicular dysplasia. Veterinary Record. 1995;137:412. doi: 10.1136/vr.137.16.412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimbow K, Horikoshi T. The nature and significance of macromelanosomes in pigmented skin lesions. American Journal of Dermatopathology. 1982;4:413–20. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halaban R, Hebert DN, Fisher DE. Biology of melanocytes. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al., editors. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomita Y, Suzuki T. Genetics of pigmentary disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 2004;131C:75–81. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boissy RE. Melanosome transfer to and translocation in the keratinocyte. Experimental Dermatology. 2003;12:5–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.12.s2.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seabra MC, Coudrier E. Rab GTPases and myosin motors in organelle motility. Traffic. 2004;5:393–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniak M. Organelle transport: a park-and-ride system for melanosomes. Current Biology. 2003;13:R917–R919. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griscelli C, Durandy A, Guy-Grand D, et al. A syndrome associating partial albinism and immunodeficiency. American Journal of Medicine. 1978;65:691–702. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90858-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menasche G, Hsuan HH, Sanal O, et al. Griscelli syndrome restricted to hypopigmentation results from a melanophilin defect (GS3) or a MYO5A F-exon deletion (GS1) Journal of Clinical Investigation. 112:450–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI18264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pastural E, Barrat FJ, Dufourcq-Laglouse R, et al. Griscelli disease maps to chromosome 15q21 and is associated with mutations in the myosin-Va gene. Nature Genetics. 1997;16:289–92. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menasche G, Pastural E, Feldmann J, et al. Mutations in RAB27A cause Griscelli syndrome associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:173–6. doi: 10.1038/76024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancini AJ, Chan LS, Paller AS. Partial albinism with immunodeficiency: Griscelli syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. American Academy of Dermatology. 1998;38:295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercer JA, Seperack PK, Strobel MC, et al. Novel myosins heavy chain encoded by murine dilute coat colour locus. Nature. 1991;349:709–13. doi: 10.1038/349709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson SM, Yip R, Swing DA, et al. A mutation in Rab27A causes the vesicle transport defects observed in ashen mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2000;57:7933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140212797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matesic LE, Yip R, Reuss AE, et al. Mutations in Mlph, encoding a member of Rab effector family, cause the melanosome transport defects observed in leaden mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2001;98:10238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181336698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philipp U, Hamann H, Mecklenburg L, et al. Polymorphism within the canine MLPH gene are associated with dilute coat color in dogs. BMC Genetics. 2005;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute of Health. [Accessed 4/8/2005.];NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Available at: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/references/phspol.htm.

- 26.CIOMS. Alternatives to Laboratory Animals. Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences; 1985. International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein C, Philippe N, Le Deist F, et al. Partial albinism with immunodeficiency (Griscelli syndrome) Journal of Pediatrics. 1994;125:886–95. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE. Pigmentary abnormalities. In: Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE, Muller, Kirk’s, editors. Small Animal Dermatology. 6. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2001. pp. 1005–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yager JA, Wilcock BP. Atrophic dermatoses. In: Yager JA, Wilcock BP, editors. Color Atlas and Text of Surgical Pathology of the Dog and Cat. London: Mosby; 1994. pp. 217–240. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberto F, Cerundolo R, Restucci B, et al. Colour dilution alopecia (CDA) in ten Yorkshire terriers. Veterinary Dermatology. 1995;6:171–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.1995.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beco L, Fontaine J, Gross TL, et al. Colour dilution alopecia in seven Dachshunds. A clinical study and the hereditary, microscopical and ultrastructural aspect of the disease. Veterinary Dermatology. 1996;7:91–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.1996.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross TL, Ihrke PJ. Inflammatory, dysplastic, and degenerative diseases. In: Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, editors. Veterinary Dermatopathology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1992. pp. 9–326. [Google Scholar]