Highlights

► Spider phobic girls show enhanced late positivity after psychotherapy. ► Reduced overall disgust proneness after psychotherapy. ► Spider phobia should already be treated in childhood.

Keywords: Spider phobia, Children, ERP, P300, LPP, Disgust proneness, Anxiety, Cognitive-behavioral therapy, Exposure

Abstract

Neurobiological studies have demonstrated that psychotherapy is able to alter brain function in adults, however little exists on this topic with respect to children. This waiting-list controlled investigation focused on therapy-related changes of the P300 and the late positive potential (LPP) in 8- to 13-year-old spider phobic girls. Thirty-two patients were presented with phobia-relevant, generally disgust-inducing, fear-inducing, and affectively neutral pictures while an electroencephalogram was recorded. Participants received one session of up to 4 h of cognitive-behavioral exposure therapy. Treated children showed enhanced amplitudes of the LPP at frontal sites in response to spider pictures. This result is interpreted to reflect an improvement in controlled attentional engagement and is in line with already existing data for adult females. Moreover, the girls showed a therapy-specific reduction in overall disgust proneness, as well as in experienced arousal and disgust when viewing disgust pictures. Thus, exposure therapy seems to have broad effects in children.

1. Introduction

In the last years, there is increasing interest in neurobiological changes due to psychotherapy of specific phobia (for reviews, see Beauregard, 2009; Porto et al., 2009). Some research on correlates of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in spider phobia has been done with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI, e.g., Schienle et al., 2007, 2009; Straube et al., 2006) using spider pictures for symptom provocation. The therapy-effect in the study by Straube et al. (2006) consisted of a reduction of hyperactivation in the anterior ventral insula reflecting a habituation of the somatic fear response. In contrast, Schienle et al. (2007) found enhanced activation in a large prefrontal area (i.e., the medial orbitofrontal cortex extending to the anterior cingulate cortex) after CBT, which was maintained in a 6-month follow-up session (Schienle et al., 2009). The effect was interpreted as a correlate of successful cognitive restructuring, mainly reflecting the relearning of stimulus-reinforcement associations and improvements in emotion regulation.

Superior to fMRI, the high temporal resolution of event-related potentials (ERPs) makes them a very promising tool to study neural responses toward phobic stimuli. There are two relevant ERP positivities within this context that are maximal at parietal recording sites. The P300 peaks between 300 and 500 ms following picture onset. The late positive potential (LPP) is a more sustained deflection, starting around 500 ms, which can be observed up to 6 s after picture onset (Pastor et al., 2008). The LPP tends to become more frontally distributed over time (Foti et al., 2009; Foti and Hajcak, 2008). Both components have repeatedly been shown to reflect increased attention toward motivationally relevant stimuli. Whereas the P300 has been linked to automatic attention processes, the LPP can be utilized as a measure of controlled attention and emotion regulation (for a review see Olofsson et al., 2008).

There are a handful of studies exploring effects of symptom provocation in spider phobics relative to healthy controls during passive picture viewing in adults (Michalowski et al., 2009; Miltner et al., 2005; Mühlberger et al., 2006; Schienle et al., 2008; Leutgeb et al., 2009) and children (Leutgeb et al., 2010). These studies consistently showed enhanced amplitudes of the P300 (combined for all studies: 280–520 ms) and early time frames of the LPP (combined for all studies: 428–800 ms) in phobics relative to controls during exposure. Results might be interpreted as effects of relatively fast and reflexive motivated attention. The ERP enhancement was specific for the spider condition and was not observed for other disorder-irrelevant emotion categories (e.g., fear, disgust; Schienle et al., 2008; Leutgeb et al., 2009, 2010).

In contrast to effects of symptom provocation, changes in ERPs after psychotherapy have hardly been investigated. A single published study by Leutgeb et al. (2009) reported a statistically significant change in late positivity in treated spider phobic adult females. Relative to a waiting-list group the treated patients showed enhanced amplitudes in response to spider pictures at fronto-central sites in a very late time window of the LPP from 800 to 1500 ms. The effect was specific for the disorder-relevant material as there were no changes in response to other picture categories (fear, disgust, neutral). Data were interpreted to reflect improved control of attentional direction during confrontation with spiders. This interpretation is in line with already existing studies showing that the voluntarily direction of attention is able to enhance the amplitude of late LPP amplitudes (Dunning and Hajcak, 2009; Ferrari et al., 2008; Hajcak et al., 2009; Keil et al., 2005; Schupp et al., 2007). Leutgeb et al. (2009) found no therapy-related changes of the P300 or the early LPP in spider phobic women. Consequently, it seems rather difficult to change these fast, automatic attentional processes in spider phobics by means of psychotherapy.

To our knowledge, there are no published ERP studies on therapy effects with spider phobic children. Generally, there is evidence that ERP latencies grow shorter with child development, indicating higher processing speed. However, studies showed that late positive components are similar in adults and children. The P300 is present even in early childhood, although latencies are longer and amplitudes are higher reflecting lower processing efficiency (for a review, see Fox et al., 2006).

Spider phobic patients experience extreme feelings of fear when confronted with spiders. However, they also report strong feelings of disgust for spiders. It has repeatedly been argued that specific phobia might be disgust-based rather than fear-based (for a review, see Olatunji et al., 2010). In line with this, several studies with spider phobics have hypothesized a role of overall disgust proneness in the etiology and maintenance of the disorderin adults (e.g., Tolin et al., 1997) and children (Muris et al., 2008a). In a study by De Jong et al. (2002) spider phobic women displayed heightened overall disgust proneness and a strong disgust response when exposed to disorder-irrelevant disgust elicitors. Muris et al. (2008a) reported significant correlations between symptoms of spider phobia and dispositional disgust in 9- to 13-year-old children. Additionally, De Jong et al. (1997) showed that 9- to 14-year-old spider phobic girls displayed an elevated overall disgust proneness. In a previous study we were also able to show heightened overall disgust-proneness in spider phobic children relative to controls (Leutgeb et al., 2010) which was accompanied by heightened average facial electromyographic activity of the levator labii and the corrugator supercilii in response to spider and disgust pictures. However, there are also studies that failed to find an overall heightened disgust proneness in adult spider phobics (Leutgeb et al., 2009; Schienle et al., 2008). In a recent study by Muris et al. (2008b) children, who had received disgust-related information about unknown animals, not only experienced a higher level of disgust but also displayed an increase in fear beliefs related to these animals. The authors concluded that there is an increased risk to develop fear for a stimulus that evokes disgust. De Jong and Muris (2002) reached a similar conclusion, as they found that the possibility of making involuntarily contact with a disgusting stimulus (i.e., the spider) is the essence of spider phobia in 10- to 14-year-old girls.

The present study is an effort to examine therapy-related changes in electrocortical correlates of spider phobic children. Patients passively viewed pictures (showing spiders, fear inducing, disgust inducing and neutral contents) while the EEG was recorded before and after exposure therapy. The therapy group was compared to a waiting-list group. We expected a reduction in phobic symptoms and in experienced fear, arousal and disgust as well as a rise in experienced positive affect during exposure in the therapy group relative to a waiting-list group. Moreover, we expected a therapy-induced enhancement of the fronto-central LPP specifically to spider pictures. Additionally, we were interested if CBT also has an impact on overall disgust proneness and trait anxiety.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty-two right-handed and non-medicated girls aged from 8 to 13 years participated in the current investigation. Female participants were chosen because of the higher prevalence of spider phobia in females as compared to males (Essau et al., 2000; Fredrikson et al., 1996). All girls suffered from spider phobia (DSM-IV-TR: 300.29). Participants were randomly assigned to either a therapy group (N = 15) or a waiting-list group (N = 17). The two groups were comparable with respect to age (M (SD): therapy group = 137.5 (15.5) months; waiting-list group = 132.9 (16.9) months). Children were recruited via articles in local newspapers. After the nature of the study had been explained to them, all girls and their caregivers gave written informed consent. Diagnoses were made by a board-certified clinical psychologist. The study was approved by a local ethic committee. Participants received exposure therapy for free and were compensated with 15 € for their participation.

2.2. Procedure

A diagnostic session, consisting of a standardized clinical interview for children (Unnewehr et al., 1995) and an interview checking diagnostic criteria of spider phobia according to the DSM IV-TR (APA, 2000), was conducted at the beginning of the investigation. Additionally, children filled out the spider Phobia Questionnaire for Children (SPQ-C, Kindt et al., 1996), a child-adapted version of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Disgust Proneness (QADS, Schienle et al., 2002) and the trait-scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C, Spielberger et al., 1973). Furthermore, children underwent a behavior avoidance test (BAT). A spider (Tegenaria atrica, approximately 3 cm in size) was put in a transparent case and placed on a table 5 m from the participant who was then instructed to approach the box, open it and take the spider on her hand. Participants who opened the box were excluded from the study. Subsequently, a diagnostic session with the caregiver, consisting of a clinical interview (Unnewehr et al., 1995; parent version) and an interview checking diagnostic criteria of spider phobia according to the DSM IV-TR (APA, 2000), was conducted. Diagnoses were determined on basis of child and parent reports according to the DSM IV-TR (APA, 2000) criteria. Patients who suffered from any other mental disorder than spider phobia were excluded from the sample.

One week later children were exposed to a total of 130 pictures during EEG recording. Pictures represented four different categories: ‘spider’, ‘neutral’, ‘disgust’ (e.g., snails, dirty toilet), and ‘fear’ (showing predators). Pictures were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS, Lang et al., 1999) and a second picture set (Schienle et al., 2005; Leutgeb et al., 2010)1. Per category thirty pictures were shown. Additionally, 10 positive ‘motivators’ (e.g., bunnies, kittens) were used to make children feel more comfortable during picture presentation. ‘Negative’ pictures (‘fear’, ‘disgust’) were chosen to be appropriate for children (e.g., no mutilation or violence pictures). Pictures were shown in a random order for 6 s each. Inter-stimulus intervals varied between 4 and 8 s. Children were instructed to sit as still as possible and to passively watch the pictures. Immediately after the experiment, children rated their impression of the pictures by means of the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM; Bradley and Lang, 1994) for ‘valence’ and ‘arousal’, and on two nine-point Likert scales on the dimensions ‘fear’ and ‘disgust’ (range 1–9, with ‘9’ indicating that the subject felt very positive, aroused, anxious or disgusted).

One week later children of the therapy group received a single session of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) according to Öst (1989), which lasted for a maximum of 4 h. The therapy consisted of detailed psychoeducation about fear and spiders, and exposure in vivo with participant modeling and cognitive restructuring. Therapy was conducted by a board-certified clinical psychologist. One week after therapy, a second EEG-session with subsequent SAM rating was conducted. Additionally, children filled out the SPQ-C (Kindt et al., 1996), the child-adapted version of the QADS (Schienle et al., 2002) and the STAI-C (Spielberger et al., 1973). Children of the waiting-list group received CBT after the second EEG-session.

2.3. Electroencephalographic recording and raw data analysis

The EEG was recorded with a Brain Amp 32 system (Brain Products, Gilching) and an Easy-Cap electrode system (Falk Minow Services, Munich) from 21 sites (Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8, C3, C4, T7, T8, P3, P4, P7, P8, O1, O2, Fz, Cz, Pz, Tp9, Tp10). All sites were referenced to FCz during the recording. A bipolar horizontal electrooculogram (EOG) was recorded from the epicanthus of each eye, and a bipolar vertical EOG was recorded from the supra- and infra-orbital position of the right eye. The EEG and the EOG were recorded with Ag/AgCl electrodes. The sites on the participants’ scalp and face were cleaned with alcohol and gently abraded prior to the placement of the electrodes. All impedances of the EEG electrodes were below 5 kΩ. EEG data were sampled with 2500 Hz and passband was set to 0.016–1000 Hz.

Analyses were performed with Brain Vision Analyzer software Version 2.0 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). EEG data were down-sampled to 250 Hz. Raw data were visually inspected for sections with movement artifacts, which were removed. Independent component analysis (ICA) was computed in order to correct for EOG artifacts. EOG relevant independent components were identified by visual inspection and comparison to EOG channels. Afterwards, an average reference was computed for further processing of the data and statistical analyses. EEG data were segmented into epochs of 1700 ms starting 200 ms before the onset of the stimulus. The later epochs were not analyzed due to an increasing number of movement artifacts. Subsequently, segments were visually inspected to discard remaining smaller artifacts. After artifact correction data were low-pass filtered (20 Hz, 24 dB/octave) and a baseline correction was performed using the first 200 ms asa reference. Epochs were averaged separately for each condition.

Participants were excluded from subsequent analyses if there remained less than 15 artifact-free trials in a single category. The mean numbers of artifact-free trials were as follow: therapy group/session 1: spider = 27, neutral = 27, disgust = 26, fear = 28; therapy group/session 2: spider = 26, neutral = 26, disgust = 26, fear = 27; waiting-list group/session 1: spider = 27, neutral = 27, disgust = 27, fear = 28; waiting-list group/session 2: spider = 28, neutral = 27, disgust = 28, fear = 28.

Magnitudes of the P300 were extracted via average amplitudes for a time window from 340 to 500 ms. Magnitudes of the LPP were extracted via average amplitudes for a time window from 600 to 1200 ms. As ERP latencies are known to become shorter with age in children, but still show greater variability as compared to adults, we chose this broad time window to account for these inter-individual differences. Analyses were conducted for three electrode sites (Fz, Cz, Pz) separately.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaires and affective ratings

Questionnaire data were submitted separately to 2 × 2 repeated measurement ANOVAs with factors time (session 1 and session 2) and group (therapy group and waiting-list group).

Analyses revealed a significant time x group interaction for the SPQ-C (F(1,30) = 100.0, p < .001; see Table 1). Participants of the therapy group showed significant reductions in SPQ-C scores (t(14) = 12.5, p < .001), while participants of the waiting-list group showed no change (p = .495). Between groups t-tests revealed that therapy and waiting-list group did not differ at session 1 (p = .512), but that therapy group participants showed significantly lower SPQ-C scores in session 2 than waiting-list group participants (t(30) = 9.2, p < .001).

Table 1.

Questionnaire data (SPQ-C, QADS-C, STAI-C) and affective ratings of spider and neutral pictures (means, M and standard deviations, SD) of therapy and waiting-list group participants before (session 1) and after (session 2) successful therapy or time of waiting.

| Therapy group M (SD) |

Waiting-list group M (SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 1 | Session 2 | |

| SPQ-C | 18.7 (2.8) | 5.27 (3.9) | 17.9 (3.4) | 17.4 (3.6) |

| QADS-C | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.7) |

| STAI-C | 36.1 (7.8) | 32.6 (7.0) | 33.5 (5.7) | 35.2 (7.5) |

| Spider pictures | ||||

| Valence | 1.7 (0.9) | 5.7 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.1) |

| Arousal | 6.9 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.4) | 6.5 (1.7) | 6.5 (1.8) |

| Fear | 6.7 (1.9) | 1.5 (0.7) | 5.6 (1.9) | 5.5 (2.0) |

| Disgust | 6.0 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.0) | 6.8 (2.0) | 5.9 (2.6) |

| Neutral pictures | ||||

| Valence | 6.2 (1.8) | 6.6 (2.0) | 7.4 (1.9) | 7.9 (1.7) |

| Arousal | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| Fear | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Disgust | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Disgust pictures | ||||

| Valence | 2.8 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.3) |

| Arousal | 4.8 (2.0) | 3.0 (1.7) | 4.7 (2.1) | 4.7 (2.0) |

| Fear | 2.1 (2.2) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.7 (1.6) |

| Disgust | 6.7 (2.0) | 4.4 (1.8) | 6.4 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.2) |

| Fear pictures | ||||

| Valence | 5.5 (2.1) | 6.0 (2.0) | 5.0 (2.0) | 6.8 (2.0) |

| Arousal | 2.5 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) |

| Fear | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.4 (0.7) | 2.2 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.2) |

| Disgust | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.5) |

Analyses revealed a significant time x group interaction for the QADS-C (F(1,30) = 8.6, p = .006; see Table 1). Participants of the therapy group showed significant reductions in QADS-C scores (t(14) = 3.6, p = .003), while participants of the waiting-list group showed no change (p = .124). Between groups t-tests revealed that therapy- and waiting-list group did not differ at session 1 (p = .594), that therapy group participants showed significantly lower QADS-C scores in session 2 than waiting-list group participants (t(30) = 2.2, p = .036).

Analyses revealed a significant time x group interaction for the STAI-C (F(1,30) = 7.3, p = .011; see Table 1). Within-groups t-tests revealed significant reductions in STAI-C scores (t(14) = 2.2, p = .045) for participants of the therapy group, while participants of the waiting-list group showed no change (p = .161). However, between groups t-tests revealed that the groups did not differ significantly at session 1 or 2 (all p > .299).

Affective ratings (valence, arousal, fear, disgust) were submitted separately to 2 × 2 × 4 repeated measurements ANOVAs with factors time (session 1 and session 2), group (therapy group and waiting-list group), and category (spider, neutral, disgust and fear). To clarify significant interactions, further analyses were conducted by means of within groups one-way ANOVAs with post hoc t-tests for repeated measurements as well as between groups t-tests.

In the therapy group pronounced changes occurred in affective ratings from session 1 to session 2 in response to spider pictures (see Table 1). We showed significant time x group x category interactions for experienced valence (F(3,90) = 17.1, p < .001), arousal (F(3,90) = 14.5, p < .001), fear (F(3,90) = 16.3, p < .001), and disgust (F(3,90) = 11.1, p = .001). Participants of the therapy group showed a significant increase in valence (t(14) = 7.2, p < .001) as well as a significant reduction in experienced arousal (t(14) = 9.9, p < .001), fear (t(14) = 10.6, p < .001), and disgust (t(14) = 5.7, p < .001) in response to spider pictures. There were no changes in affective ratings of spider pictures from session 1 to session 2 in the waiting-list group (all p > .083).

In both groups there were no changes in affective ratings of neutral pictures from session 1 to session 2 (all p > .132).

Participants of the therapy group showed a significant reduction in experienced arousal (t(14) = 2.9, p = .011) and disgust (t(14) = 4.4, p < .001) in response to disgust pictures from session 1 to session 2, whereas there was no change in the other affective ratings of disgust pictures (all p > .132). In the waiting-list group there were no changes in affective ratings of disgust pictures from session 1 to session 2(all p > .236).

In the therapy group there were no changes in affective ratings of fear pictures (all p > .088). In the waiting list group there was a significant increase in valence (t(16) = 5.4, p < .001) in response to fear pictures from session 1 to session 2, whereas there was no change in the other affective ratings of fear pictures (all p > .136).

Between-groups t-tests showed that there were no group-differences for affective ratings of any picture category at session 1 (all p > .088). At session 2 therapy group participants showed significantly higher valence (t(30) = 6.8, p < .001), and lower arousal (t(30) = 6.8, p < .001), fear (t(30) = 7.3, p < .001), and disgust (t(30) = 5.5, p < .001) ratings for spider pictures than waiting-list group participants. At session 2 groups did not differ in their affective ratings of neutral or fear pictures (all p > .063). At session 2 therapy group participants showed significantly higher valence (t(30) = 2.1, p = .048), and lower arousal (t(30) = 2.5, p = .020) and disgust (t(30) = 3.1, p = .005) ratings for disgust pictures than waiting-list group participants, while they did not differ in their fear rating (p = .220).

3.2. P300 (340–500 ms)

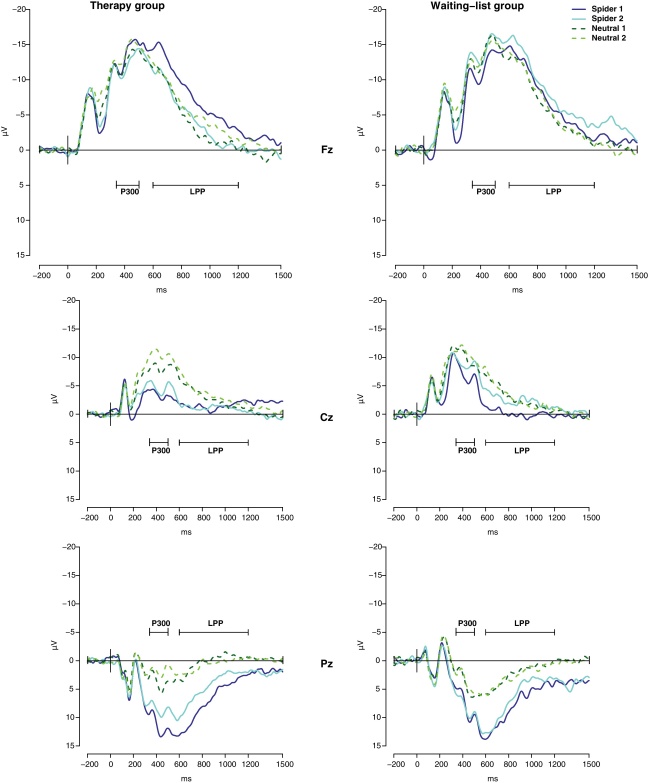

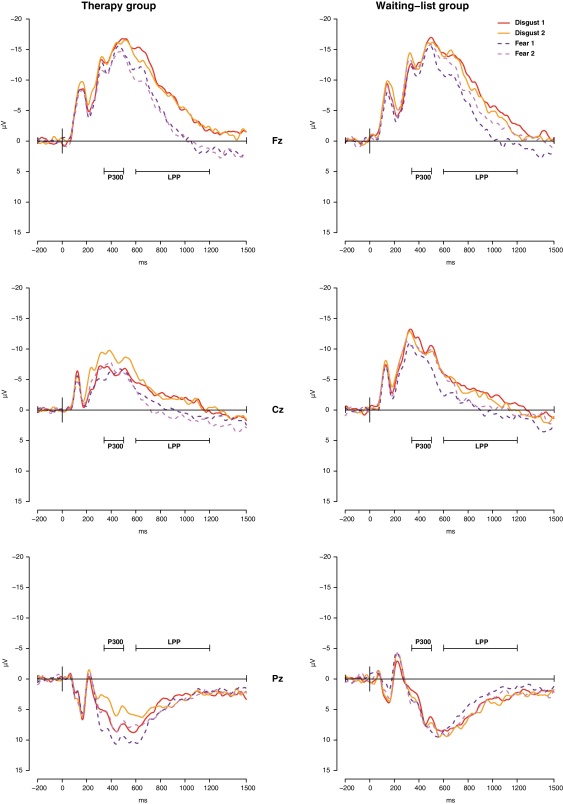

Grand average waveforms of therapy group and waiting-list group participants before (1) and after (2) therapy or time of waiting at Fz, Cz, and Pz are shown in Fig. 1 for spider and neutral pictures and in Fig. 2 for disgust and fear pictures.

Fig. 1.

Grand average waveforms of therapy group and waiting-list group participants for spider and neutral pictures before (1) and after (2) therapy or time of waiting at Fz, Cz, and Pz.

Fig. 2.

Grand average waveforms of therapy group and waiting-list group participants for disgust and fear pictures before (1) and after (2) therapy or time of waiting at Fz, Cz, and Pz.

EEG data (P300, LPP) were submitted to 2 × 2 × 4 repeated measurements ANOVAs with the factors time (session 1 and session 2), group (therapy group and waiting-list group), and category (spider, neutral, disgust and fear) as we hypothesized therapy-induced changes to disorder-specific stimuli. No further analyses were conducted if the repeated measurements ANOVA had yielded non-significant results. To clarify significant interactions, further analyses were conducted by means of within groups one-way ANOVAs with post hoc t-tests for repeated measurements as well as between groups t-tests.

Fz: Analyses revealed a significant time x group x category interaction for the P300 at Fz (F(3,90) = 2.8, p = .047). Within the therapy group responses to spider pictures did not differ significantly from the other picture categories at session 1 (all p > .375). At session 2 spider pictures elicited higher amplitudes than disgust and neutral pictures (all p < .045) while there was no difference between spider and fear pictures (p = .225). The therapy group showed no change in P300 amplitudes from session 1 to session 2 (all p > .116). Within the waiting-list group there was no difference between spider pictures and the other picture categories at both sessions (all p > .079). The waiting-list group showed a reduction of P300 amplitudes in response to spider pictures (t(16) = 2.3, p = .035), but not to any other picture category (all p > .590). There were no differences between groups at session 1 (all p > .340), or at session 2 (all p > .356).

Cz: Analyses revealed a significant time x group x category interaction for the P300 at Cz (F(3,90) = 3.1, p = .030). Within the therapy group spider pictures elicited higher amplitudes than all other picture categories at both sessions (all p < .006). The therapy group showed a reduction of P300 amplitudes from session 1 to session 2 in response to disgust pictures (t(14) = 2.4, p = .034) and neutral pictures (t(14) = 2.2, p = .049), while there were no changes in P300 amplitudes from session 1 to session 2 in response to the other picture categories (all p > .331). Within the waiting-list group spider pictures elicited higher amplitudes than disgust and neutral pictures at session 1 (all p < .030) and did not differ from fear pictures (p = .198). At session 2 spider pictures elicited higher amplitudes than neutral pictures (p = .032) but did not differ from disgust or fear pictures (all p > .211). The waiting-list group showed no changes in P300 amplitudes from session 1 to session 2 (all p > .165). At session 1 the waiting-list group showed significantly higher amplitudes of the P300 for disgust pictures relative to the therapy group (t(30) = 2.3, p = .031) while there were no differences between groups for the other picture categories (all p > .171) at session 1 or at session 2 (all p > .099).

Pz: Analyses revealed no significant time x group x category interaction for the P300 at Pz (F(3,90) = 0.5, p = .672).

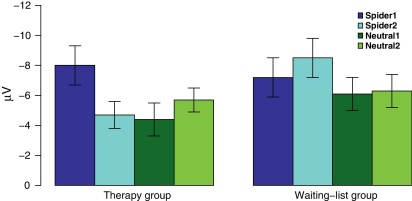

3.3. Late positive potential (LPP, 600–1200 ms)

Fz: At Fz analyses revealed a significant time x group x category interaction for the LPP (F(3,90) = 3.2, p = .028). Within the therapy group spider pictures elicited smaller amplitudes than neutral and fear pictures at session 1 (all p < .024), while spider and disgust pictures did not differ from each other. At session 2 spider pictures elicited higher amplitudes than disgust pictures (p = .015) and smaller amplitudes than fear pictures (p = .039). Responses to spider and neutral pictures did not differ. The therapy group showed enhanced LPP amplitudes in response to spider pictures from session 1 to session 2 (t(14) = 2.7, p = .018; see Fig. 3), but not for in response to any other picture category (all p > .257). Within the waiting-list group spider pictures elicited smaller amplitudes than fear pictures at session 1 (p = .008), while spider pictures did not differ from disgust or fear pictures (all p > .264). At session 2 spider pictures elicited smaller amplitudes than fear pictures (p = .036) and did not differ from disgust or neutral pictures (all p > .154). Within the waiting-list group there was no change in amplitudes to any picture category (all p > .126). There were no differences between groups at session 1 (all p > .286). At session 2 therapy group participants showed significantly higher LPP amplitudes than waiting-list patients in response to spider pictures (t(30) = 2.3, p = .030) and fear pictures (t(30) = 2.4, p = .021), while there were no significant differences between groups for neutral or disgust pictures (all p > .639).

Fig. 3.

Average amplitudes of the LPP of therapy group and waiting-list group participants for spider and neutral pictures before (1) and after (2) therapy or time of waiting at Fz.

Cz and Pz: At Cz and Pz there were no significant time x group x category interactions for the late LPP (Cz: F(3,90) = 2.6, p = .055; Pz: F(3,90) = 0.3, p = .818).

4. Discussion

Spider phobia is about as common in children (Muris et al., 1999) as in adults (Fredrikson et al., 1996). With a mean age of six years spider phobia shows a rather early onset (Becker et al., 2007). CBT is the treatment of choice for spider phobia (Zlomke and Davis, 2008). Öst (1989) and Öst et al. (2001) reported that spider phobia can be treated very successfully, as clinical improvement rates are 90% in children and 85–90% in adults. All of the 32 children who participated in the current study were successfully treated and all of them were able to hold a living spider in their hands after a maximum of 4 h exposure therapy. Possible reasons that children despite these promising results do not receive therapy might be that parents often tend to underestimate the fears of their children (e.g., Muris et al., 2001). Moreover, phobias in childhood are often regarded as a passing phenomenon (e.g., Agras et al., 1972). However, phobias in childhood are a significant predictor of later anxiety disorders (Fichter et al., 2009) and should therefore be treated. Our results indicate that exposure therapy shows broad effects in spider phobic children. We therefore reason, that patients should more frequently be transferred to psychotherapy.

The aim of the current study was to investigate changes in late electrocortical activity and emotional experience in 8- to 13-year-old spider phobic girls after exposure therapy. To our knowledge this is the first study reporting neurobiological correlates of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in children.

After therapy, the children of the therapy group showed a pronounced rise in experienced valence and a reduction in arousal, fear and disgust during confrontation with spiders. Moreover, symptom severity (according to a disorder-specific questionnaire) dropped enormously. Children of the waiting-list group showed no change in symptom severity or in affective ratings of spiders.

With respect to event-related potentials, children of the therapy group relative to children of the waiting-list group showed an enhanced late positive potential (LPP) in a time window of 600–1200 ms after stimulus onset when confronted with spider pictures. The effect was maximal at frontal electrode sites. Moreover, the effect was specific for disorder-relevant material and not present for other emotional categories (fear, disgust and neutral). Although there was a significant group difference for LPP amplitudes in response to fear pictures at session 2, no group showed a significant change of amplitudes in response to fear pictures over time.

The enhanced amplitudes of the late LPP after exposure therapy in response to spider pictures can be interpreted to reflect controlled allocation of attention to spiders. This interpretation is in accordance with studies showing that directed attention is able to modulate the amplitude of late positivity (e.g., Ferrari et al., 2008; Hajcak et al., 2009; Schupp et al., 2007). Compared to adults, research on late positivity in children is rare. However, studies showed that the amplitude of the LPP is sensitive to emotional processing (Hajcak and Dennis, 2009; Solomon et al., 2012). It remains unclear, if the LPP is sensitive to emotion regulation instructions in children (Dennis and Hajcak, 2009; Decicco et al., 2012). However, these studies showed that the LPP in children has an almost similar time course and distribution like in adults. Enhanced amplitudes of late positivities after exposure therapy have already been shown in adult females (Leutgeb et al., 2009) indicating that the disorder has a similar neural substrate in children and adults.

There were no therapy-related changes in response to spider pictures in earlier time frames of the ERP (i.e., the P300), possibly reflecting that it is difficult to change the fast, reflexive attentional capture by spiders in spider phobics. At frontal and central electrode sites there were changes in amplitudes of the P300 from session 1 to session 2 (i.e., in response to spider pictures in the waiting-list group; disgust and neutral pictures in the therapy group). However, there were no differences between groups in response to any picture category at the second session. Moreover, the effect of motivated attention is prominent at posterior sites and no P300 component could clearly be detected at fronto-central sites.

After the therapy patients were able to voluntarily direct their attention to spiders and not to avoid them anymore even though they still experienced feelings of fear and disgust. Future investigations should study if the effect on brain activity is stable over time. Moreover, it might be possible that the reflexive attentional bias is reduced after some months of practice and daily routine with spiders. Therefore, future studies should also employ a follow-up session.

Although therapy was restricted to exposure to spiders, there were additional positive effects: After therapy children of the therapy group showed a significant reduction in overall disgust proneness, although exposure therapy did only target feelings of disgust for spiders. Additionally, treated children rated overall disgust relevant pictures as less arousing and disgusting at the second EEG session compared to the first session. In line with the study by Muris et al. (2008b), we argue that fear of spiders might be the consequence of enhanced disgust to spiders. In this context, elevated disgust proneness might represent a vulnerability factor in children for the acquisition of certain phobias. In a previous study by Leutgeb et al. (2009) adult females did not show therapy-related reductions in overall disgust sensitivity or affective ratings of disgust-relevant scenes. This leads us to the assumption that psychotherapy has broader effects in childhood than in adulthood and that vulnerability factors should be also targeted in the course of therapy in childhood. However, with respect to the electrocortical activity, there was no significant difference in response to disgust pictures between the first and the second EEG session. Overall disgust was not directly addressed during the course of exposure therapy and it therefore is not surprising, that children did not direct their attention to disgust slides, although they did not perceive them as negative and arousing like in the first EEG session. Besides changes in overall disgust proneness, there was a significant reduction in STAI-C-scores in the therapy group after CBT. This drop in overall anxiousness in children receiving exposure therapy might be due to the fact that the management of fear in general was repeatedly targeted during the course of psychoeducation.

In summary, the electrocortical correlates of exposure therapy in spider phobic children resembled those in spider phobic adults: spider phobic girls as well as adults showed enhanced late positive potential amplitudes in response to spider pictures after therapy. In children, the effect was maximal at frontal electrode sites from 600 to 1200 ms. The result can be interpreted to reflect successful direction of attention toward spiders. Moreover, exposure therapy reduced overall disgust proneness in children of the therapy group.

5. Conclusions

The study indicates broad effects of exposure therapy in spider phobic children. It effects the direction of attention as well as emotional experiencing (i.e., feelings of disgust) and underlying electrocortical correlates. Further research should be conducted to explore if exposure therapy could be improved by addressing vulnerability factors, like overall disgust proneness.

Acknowledgments

The authors kindly thank the children who participated in the present study. The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P21379-B18.

Footnotes

The numbers of the IAPS pictures (Lang et al., 1999) used were the following: neutral (7000, 7009, 7010, 7034, 7050, 7080, 7100, 7140, 7170, 7175, 7190, 7205, 7211), fear (0015, 1114, 1930), disgust (0018, 0019, 0020, 0021, 0022, 0025, 0026, 0027, 0028, 0031, 0032, 1274, 1275, 9008,9300, 9301, 9320), positive motivators (1440, 1463, 1750, 1999, 2071, 2311, 2387, 7340, 7410, 7460). Seventeen neutral, 24 disgust, 27 fear and all spider pictures were taken from validated picture sets of the authors (Schienle et al., 2005; Leutgeb et al., 2010).

References

- Agras W.S., Chapin H.N., Oliveau D.C. The natural history of phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;26:315–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750220025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard M. Effect of mind on brain activity: evidence from neuroimaging studies of psychotherapy and placebo effect. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;63:5–16. doi: 10.1080/08039480802421182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker E.S., Rinck M., Türke V., Krause P., Goodwin R., Neumer S., Margraf J. Epidemiology of specific phobia subtypes: findings from the Dresden Mental Health Study. European Psychiatry. 2007;22:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M.M., Lang P.J. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decicco J.M., Solomon B., Dennis T.A. Neural correlates of cognitive reappraisal in children: an ERP study. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;2:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P.J., Andrea H., Muris P. Spider phobia in children: disgust and fear before and after treatment. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1997;35:559–562. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P.J., Muris P. Spider phobia: interaction of disgust and perceived likelihood of involuntary physical contact. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:51–65. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P.J., Peters M., Vanderhallen I. Disgust and disgust sensitivity in spider phobia: facial EMG in response to spider and oral disgust imagery. Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:477–493. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis T.A., Hajcak G. The late positive potential: a neurophysiological marker for emotion regulation in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1373–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning J.P., Hajcak G. See no evil: directing visual attention within unpleasant images modulates the electrocortical response. Psychophysiology. 2009;46:28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau C.A., Conradt J., Petermann F. Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of specific phobia in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:221–231. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari V., Codispoti M., Cardinale R., Bradley M.M. Directed and motivated attention during processing of natural scenes. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:1753–1761. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichter M.M., Kohlboeck G., Quadflieg N., Wyschkon A., Esser G. From childhood to adult age: 18-year longitudinal results and prediction of the course of mental disorders in the community. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:792–803. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0501-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D., Hajcak G. Deconstructing reappraisal: descriptions preceding arousing pictures modulate the subsequent neural response. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:977–988. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D., Hajcak G., Dien J. Differentiating neural responses to emotional pictures: evidence from temporal-spatial PCA. Psychophysiology. 2009;46:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N.A., Hane A.A., Pérez-Edgar K. Psychophysiological methods for the study of developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D., Cohen D.J., editors. Developmental Psychopathology. Wiley; New Jersey: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrikson M., Annas P., Fischer G., Wik P. Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G., Dennis T.A. Brain potentials during affective picture processing inchildren. Biological Psychology. 2009;80:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G., Dunning J.P., Foti D. Motivated and controlled attention to emotion: time course of the late positive potential. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2009;120:505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A., Moratti S., Sabatinelli D., Bradley M.M., Lang P.J. Additive effects of emotional content and spatial selective attention on electrocortical facilitation. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:1187–1197. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindt M., Brosschot J.F., Muris P. Spider phobia questionnaire for children (SPQ-C): a psychometric study and normative data. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:277–282. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P.J., Bradley M., Cuthbert B. Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida; Gainsville: 1999. International Affective Picture System. [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb V., Schäfer A., Köchel A., Scharmüller W., Schienle A. Psychophysiology of spider phobia in 8- to 12-year old girls. Biological Psychology. 2010;85:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb V., Schäfer A., Schienle A. An event-related potential study on exposure therapy for patients suffering from spider phobia. Biological Psychology. 2009;82:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalowski J.M., Melzig C.A., Stockburger J., Schupp H.T., Hamm A.O. Brain dynamics in spider-phobic individuals exposed to phobia-relevant and other emotional stimuli. Emotion. 2009;9:306–315. doi: 10.1037/a0015550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltner W.H.R., Trippe R.H., Krieschel S., Gutberlet I., Hecht H., Weiss T. Event-related brain potentials and affective responses to threat in spider/snake-phobic and non-phobic subjects. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2005;57:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlberger A., Wiedemann G., Herrmann M.J., Pauli P. Phylo- and ontogenetic fears and the expectation of danger: differences between spider- and flight-phobic-subjects in cognitive and physiological responses to disorder-specific stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:580–589. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Mayer B., Huijding J., Konings T. A dirty animal is a scary animal! Effects of disgust-related information on fear beliefs in children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Merckelbach H., Ollendick T.H., King N.J., Bogie N. Children's nighttime fears: parent–child ratings of frequency, content, origins, coping behaviors and severity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:13–28. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Schmidt H., Merckelbach H. The structure of specific phobia symptoms among children and adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:863–868. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., van der Heiden S., Rassin E. Disgust sensitivity and psychopathological symptoms in non-clinical children. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2008;39:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst L.G. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst L.G., Svensson L., Hellström K., Lindwall R. One-session treatment of specific phobias in youths: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:814–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B.O., Cisler J., McKay D., Phillips M.L. Is disgust associated with psychopathology? Emerging research in the anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2010;175:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson J.K., Nordin S., Sequeira H., Polich J. Affective picture processing: an integrative review of ERP findings. Biological Psychology. 2008;77:247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor M.C., Bradley M.M., Löw A., Versace F., Moltó J., Lang P.J. Affective picture perception: emotion, context, and the late positive potential. Brain Research. 2008;1189:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porto P.R., Oliveira L., Mari J., Volchan E., Figueira I., Ventura P. Does cognitive behavioral therapy change the brain? A systematic review of neuroimaging in anxiety disorders. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;21:114–125. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Hermann A., Rohrmann S., Vaitl D. Symptom provocation and reduction in patients suffering from spider phobia: an fMRI study on exposure therapy. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;257:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0754-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Naumann E. Event-related brain potentials of spider phobics to disorder-relevant, generally disgust- and fear-inducing pictures. Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;22:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Stark R., Vaitl D. Long-term effects of cognitive behavior therapy on brain activation in spider phobia. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;172:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Walter B., Stark R., Vaitl D. Brain activation of spider phobics towards disorder-relevant, generally disgust- and fear-inducing pictures. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;388:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Walter B., Stark R., Vaitl D. Ein fragebogen zur erfassung der ekelempfindlichkeit, FEE (a questionnaire for the assessment of disgust sensitivity QADS) Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie. 2002;31:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Schupp H.T., Stockburger J., Codispoti M., Junghöfer M., Weike A.I., Hamm A. Selective visual attention to emotion. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:1082–1089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3223-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon B., DeCicco J.M., Dennis T.A. Emotional picture processing in children: an ERP study. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;2:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D., Edwards C.D., Lushene R.E., Montouri J., Platzek D. Consulting Psychologist Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1973. STAIC Preliminary Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Straube T., Glauer M., Dilger S., Mentzel H.J., Miltner W.H.R. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on brain activation in specific phobia. NeuroImage. 2006;29:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D.F., Lohr J.M., Sawchuck C.N., Lee T.C. Disgust and disgust sensitivity in blood-injection-injury and spider phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:949–953. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unnewehr S., Schneider S., Margraf J. Springer; Berlin: 1995. Diagnostisches Interview bei Psychischen Störungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter (Kinder-DIPS) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlomke K., Davis T.E. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:207–223. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]