Abstract

Background

Information about adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectum is scarce due to its extremely low incidence.

Objective

To examine the prognostic significance of a histological diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma compared to adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum.

Design

Retrospective study.

Setting

California Cancer Regisry data from 1994 through 2004 with follow up through 2008.

Patients

Surgically treated cases of cancer of the colon and rectum excluding anus with tumor histology of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma.

Main outcome measures

Histology-specific survival analyses (using Kaplan-Meier method), and overall and colorectal-specific mortality (using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses).

Results

A total of 111,263 adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma of colon and rectal cancer cases were identified (adenocarcinoma 99.91%, and adenosquamous carcinoma: 0.09%). There was no significant difference in sex, age, race and socioeconomic status between two groups. The most common location of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma was the right colon and transverse colon. The adenosquamous carcinoma group was significantly associated with higher rate of metastasis at the time of operation (adenosquamous carcinoma: 36.56% vs. adenocarcinoma: 13.92%) and with poorly differentiated tumor grade (adenosquamous carcinoma: 65.96% vs. adenocarcinoma: 19.74%) compared to the adenocarcinoma group. The median overall survival time was significantly greater in the adenocarcinoma group (82.4 months) compared with the adenosquamous carcinoma group (35.3 months). Using multivariable hazard regression analyses, adenosquamous carcinoma histology was independently associated with increased overall mortality (Hazard Ratio: 1.67) and colorectal-specific mortality (Hazard Ratio: 1.69) compared with adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions

This is one of the largest studies of adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectum to date. This uncommon colorectal cancer subtype was associated with higher overall and colorectal-specific mortality compared with adenocarcinoma. Among colorectal cancer cases, adenosquamous carcinoma histology should be considered a poor prognostic features.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Adenosquamous Carcinoma, Colorectal Carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

More than 90 percent of colorectal neoplasms are adenocarcinomas (AC), with the majority of the remaining cases being nonepithelial histologies such as carcinoid tumors, sarcomas, and lymphoid tumors. Two other epithelial histologies, adenosquamous carcinomas (ASC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are uncommon but clearly-defined malignant tumors that that occur within the colorectum.1 Primary ASC and SCC of the colon and rectum are extremely rare clinical entities. Herxheimer described the first case of a patient with an ASC of the cecum in 1907.2

Very little population-based data exist regarding these rare CRC subtypes. Most of the data comes from individual case reports and a few small series from large institutions. The rarity of these tumors has made it a challenge to understand the biology of the disease. Also, the clinicopathologic behavior, and optimal management of these rare tumors are not defined. However, in two small series they have reported to exhibit a poorer prognosis than invasive AC alone.3,4

Using data from the California Cancer Registry (CCR), our study was intended to 1) describe the incidence, clinical and pathologic characteristics of ASC, one of the rare colorectal cancers; and 2) to determine overall survival and CRC-specific survival of ASC compared to AC of colon and rectum.

MATERIAL and METHODS

Study Population

The CCR is California’s statewide population-based cancer surveillance system and is also part of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program. Data were obtained from the CCR, which has the highest level of certification from the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. Since 1988, all cancer cases treated in California are required by law to be reported to the CCR. Standardized data collection and quality control procedures have been in place since then.5 Case reporting is estimated to be 99% for the entire state of California, with follow-up completion rates exceeding 95%.5 International Classification of Disease Codes for Oncology (ICD-O) based on World Health Organization’s criteria were used for tumor location and histology. Cases were identified using colorectal SEER primary site code for colon and rectal cancers, excluding appendiceal carcinoma and anal cancer, as described previously.6,7 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage was derived as previously described.7,8

Using CCR data, we retrospectively evaluated surgically treated cases of cancer of the colon and rectum (excluding anus) from 1994 through 2004, with follow-up through 2008. Colorectal cancer cases are included for 2 different types of histology including AC, and ASC; other types of histologies and non-surgically treated patients (chemotherapy/radiation only) were excluded from this study. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), stage at presentation (TNM classification), tumor grade and treatments (including surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiotherapy) were evaluated. SES was assigned based on the patient’s census block group (U.S. census) derived from their address at time of initial diagnosis as reported in the medical record. This SES variable is an index that utilizes education, employment characteristics, median household income, proportion of the population living 200% below the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), median rent and median housing value of census tract of residence for case and denominator population. A principal components analysis was used to identify quintiles of SES ranging from 1 the lowest, to 5 the highest.7,9 Cause of death was recorded according to International Classification of Disease (ICD) criteria in effect at the time of death.10 The last date of follow-up was either the date of death or the last date of contact. In this study, CRC-specific morality is defined as mortality caused by colorectal cancer as a primary pathology.

Statistical Analysis

The clinical characteristics, including age, gender, race, socioeconomic status quintile, cancer stage, tumor grade, and treatments were analyzed with χ2 Test for categorical variables. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to estimate overall mortality and CRC-specific mortality, comparing cases with AC, and ASC. Histological-specific survival analyses were conducted by the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression models were performed using time from diagnosis until either 1) death from colorectal cancer or 2) a censoring event (end of study period, death from another cause, or loss to follow-up). All models were adjusted to other variables known to predict survival in CRC including age, gender, race, SES, tumor grade, TNM staging and treatments. CRC-specific mortality and overall mortality were calculated from Cox Proportional Hazard Ratios, using dummy variables to account for missing data. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System 9.2 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Ethical Considerations

This study involved analyses of existing data from CCR database with no subject intervention. No identifiers were linked to subjects. This study was approved by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board under the category “exemptstatus” (Institutional Review Board 2010-7853).

RESULTS

A total of 111,263 AC and ASC colon and rectal cancer cases were identified during these 11 years; this includes 111,164 (99.91%) AC and 99 (0.09%) ASC. Table 1 shows patient characteristics of the two groups. The ratio of females:males was almost 1:1 in AC and ASC group. The mean ages of AC, and ASC patients were 69.5, and 67.0 years respectively. There was no significant difference in age group between groups. Comparing the patients younger than 60 years old between the three groups, 21.8% of AC patients were younger than 60 years old while 37.4% of ASC patients were younger than 60 years old. The majority of patients were Caucasian in the two groups (AC: 72.2% vs. ASC: 69.7%). Comparing SES, no significant difference was observed between two groups. A smaller proportion of CRC patients were observed in the lower vs. higher SES quintiles from 13.2% in the 1st Quintile to 23.4% in the 5th Quintile.

Table 1.

Patient’s characteristics adenocarcinoma (AC) vs. adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) of colon and rectum cancer

| AC | ASC | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients (%) | 111,164 (99.91%) | 99 (0.09%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 56541 (50.9%) | 48(48.5%) | 0.636 |

| Female | 54623 (49.1%) | 51(51.5%) | |

| Age Group | 0.245 | ||

| 0-19 | 29 (0.03%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 20-39 | 2288 (2.1%) | 5 (5.0%) | |

| 40-49 | 6697 (6.0%) | 5 (5.0%) | |

| 50-59 | 15193 (13.7%) | 15 (15.2%) | |

| 60-69 | 25256 (22.7%) | 27 (27.3%) | |

| 70+ | 61701 (55.5%) | 47 (47.5%) | |

| Median | 71 | 69 | |

| Range (year) | 11-108 | 22-94 | |

| Ethnicity/Race | |||

| Caucasian | 80290 (72.2%) | 69 (69.7%) | 0.127 |

| African-American | 6989 (6.3%) | 4 (4.0%) | |

| Asian | 10252 (9.2%) | 6 (6.1%) | |

| Hispanic | 13124 (11.8%) | 19 (19.2%) | |

| Other | 509 (0.5%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES)** | |||

| 1st Quintile | 14624 (13.6%) | 17 (17.2%) | 0.211 |

| 2nd Quintile | 21114 (19.0%) | 11 (11.1%) | |

| 3rd Quintile | 24280 (21.8%) | 27 (27.3%) | |

| 4th Quintile | 25171 (22.6%) | 22 (22.2%) | |

| 5th Quintile | 25975 (23.0%) | 22 (22.2%) |

P-value < 0.5 considered significant

SES ranging from 1 the lowest, to 5 the highest

Table 2 shows pathologic characteristics and treatments in all groups. ASC was significantly associated with higher distant metastasis rate (stage IV) at the time of operation (ASC: 36.56%; AC: 13.92%). Also, the ASC group was associated with a higher rate of poorly differentiated tumors (ASC: 65.96%; AC: 19.74%; p<0.001). The most common location of ASC and AC was the right and transverse colon (AC: 44.0% vs. ASC: 56.3%). The most common procedure in the AC group was partial colectomy (43.6%) while subtotal colectomy (50.7%) in the ASC group was the most common procedure. Distribution of treatments rendered is shown in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Pathologic characteristics and treatment of adenocarcinoma (AC) vs. adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC)

| AC | ASC | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage (%) | <0.001 | ||

| I | 25497 (24.4%) | 6 (6.4%) | |

| II | 37461 (35.8%) | 28 (30.1%) | |

| III | 27104 (25.9%) | 25 (26.9%) | |

| IV | 14567 (13.9%) | 34 (36.6%) | |

| Histological Grade | <0.001 | ||

| Well differentiated | 10207 (9.6%) | 1(1.1%) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 74283 (70.1%) | 27(28.7%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 20928 (19.7%) | 62(66.0%) | |

| Undifferentiated | 597 (0.6%) | 4(4.2%) | |

| Location | 0.01 | ||

| Proximal and transverse colon | 48912 (44.0%) | 56(56.3%) | |

| Descending colon | 4891 (4.4%) | 0(0.0%) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 26457 (23.8%) | 14(14.1%) | |

| Rectosigmoid | 9672 (8.7%) | 8(8.5%) | |

| Rectum | 19676 (17.7%) | 18(18.3%) | |

| Unknown | 1556 (1.4%) | 3(2.8%) | |

| Radiation | 0.760 | ||

| No radiation | 100036 (90.0%) | 90(90.9%) | |

| Radiation | 11128 (10.0%) | 9(9.1%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.101 | ||

| No | 72316 (65.1%) | 55(55.6%) | |

| Yes | 34917 (31.3%) | 41(41.4%) | |

| Unknown | 3931 (3.6%) | 3(3.0%) | |

| Surgery | 0.003 | ||

| Local excision | 5386 (4.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Partial colectomy | 51267 (46.1%) | 38 (38.4%) | |

| Subtotal colectomy | 43353 (39.0%) | 41(41.4%) | |

| Total/proctocolectomy | 10291 (9.3%) | 19 (19.2%) | |

| Unknown colectomy | 867 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

P-value < 0.5 considered significant

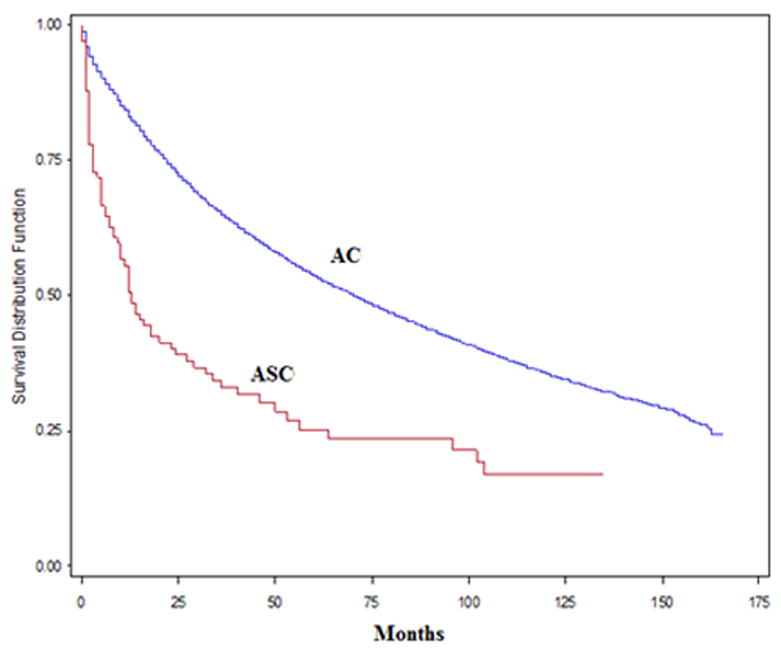

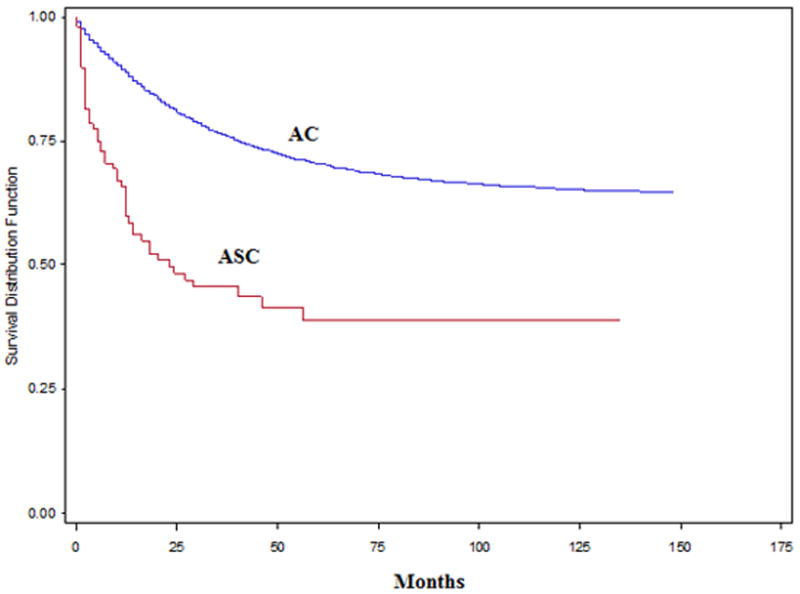

Using Kaplan Meier analyses for overall survival in this patient population, the median overal survival time was 2.33 times longer in the AC group (82.4 months) compared with the ASC group (35.3 months). Both 5-year overall and CRC-specific survival rates were significantly higher in the AC group compared with the ASC group (p<0.001), Figure 1, and 2. Table 3 shows the overall and CRC-specific survival trends of these patient groups based on distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis (stage I-III: without distant metastasis; stage IV: with distant metastasis) and overall survival regardless of distant metastasis (stage I-IV). In multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses with adjustment for patient characteristics, SES, stage, and treatments with surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy; ASC was independently associated with increased overall mortality (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.67; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.33-2.10; p<0.001) and CRC-specific mortality (HR: 1.69; 95% CI: 1.29-2.23; p<0.001) compared with AC.

Figure 1.

Overall survival rate (stage I -IV) in adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) vs. adenocarcinoma (AC)

Figure 2.

Colorectal-specific survival rate (stage I -IV) in adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) vs. adenocarcinoma (AC)

Table 3.

Five-year overall and CRC*-specific survival rate in colorectal cancer

| AC | ASC | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival rate (%) | |||

| Stage I-III | 61.3 | 37.2 | <0.001 |

| Stage IV | 7.7 | 0.0 | 0.028 |

| Stage I-IV | 53.6 | 23.5 | <0.001 |

| CRC-specific survival rate (%) | |||

| Stage I-III | 79.4 | 53.7 | <0.001 |

| Stage IV | 12.7 | 0.0 | 0.094 |

| Stage I-IV | 70.3 | 38.9 | <0.001 |

CRC indicates colorectal cancer

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that colorectal ASC comprises 0.05-0.20%11 of colorectal malignancies. Our population-based study, using data on a large number of colorectal cancer patients confirms the rarity of this tumor (ASC: 0.09%). The proportion of ASC in our study is in the previously-reported range.

Most studies have reported the occurrence of ASC in patients’ sixth and seventh decade of life.3 The mean age of patients with each types of tumors in our study was in the patients’ seventh decade (AC: 69.5 vs. ASC:67 years) and median age was 71 years in the AC group vs. 69 years in the ASC group. With regard to gender, our study showed that the percentages of females and males were similar in both ASC and AC group. Although few previous studies reported the gender distribution in ASC, their results were different and limited cases were included in these studies. Similar to our study for ASC, a study by Michelassi et al.12 showed that the percentage of male and female were identical; while Cagir et al.3 in a review of 145 ASC patients from National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) reported male predominance (57%) of ASC. As for patient race, our results show that almost 70% of patients in both groups were Caucasian. Compared with race data of California population over the last 20 years, Caucasians race is at higher risk of CRC than other races. Data on race in these rare tumors are limited; however, Cagir et al.3 found that Caucasians comprised 84% of all patients.

Although most early studies on ASC found the rectum (excluding the distal 8 cm) to be the most common site;12,13 our study shows that the most common location of ASC is in the proximal colon (similar to AC) and the least involved location was in the descending colon in both groups. Similarly in a study with a total of 56 ASC by Frizelle et al.4 showed that the right colon was the most common site of ASC. Kontozoglou and Moyana14 identified the location of ASC in 29 cases, with 41% occurring in the proximal segment, 10% in the middle segment, and 49% occurring in the distal segment of the colon. Cagir et al.3 found ASC occurred most frequently in distal segment, including the sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus (58%) followed by proximal segment (28%) and middle segment (13%).

Tumor stage and grade of differentiation at the time of diagnosis is associated with the prognosis of the patients. Our study showed that compared with AC, ASC was associated with a higher rate of advanced disease and higher rate of poor differentiation and this may explain the higher overall and CRC-specific mortality observed for ASC in the univariate analyses. This pathologic character of ASC is supported by many other studies.11,15,16 However, our multivariate analyses adjusted for differences in stage and tumor grade, along with other clinically-relevant factors – and the mortality differences remained.

We observed that patients in ASC group, after adjustment for age, gender, race, SES, location of tumor, stage of disease at diagnosis and treatment, had higher chances of both overall mortality (HR: 1.67) and CRC-specific mortality (HR: 1.69) compared with AC. Our findings are consistent with the theory that squamous features in a colonic carcinoma impart a worse prognosis.15 The survival curves in our study showed that both the five-year overall survival rate and CRC-specific survival rate were the higher in AC compared with ASC (Figure 1-2). Recent data from Jemal et al.17 reported the overall five-year survival rates in the US were 66% for colon cancer and 69% for rectal cancer. Our study, over a longer time period, showed 5-year survival rate of AC of 53.6%, and ASC of 23.5%. In the current study we observed that 5-year survival rate was higher in the AC group for stage I-III, stage IV and stage I-IV. Similarly Comer et al.18 found that the overall five-year survival rate of ASC to be 30% compared with 50% for AC. Previous studies reported similar survival rate for ASC compared with AC in early stages and lower survival rate in advanced stages.3,4,14 Frizelle et al.4 found the prognosis of ASC to be similar to AC for Stage I to II node-negative disease (Dukes A and B) and Cagir et al.3 found the survival rate for patients with ASC stages A and B1 to be similar to patients with comparably staged AC, while the patients with ASC staged B2 through D had significantly poorer survival than patients with comparably staged AC, supporting the reports of a poor prognosis associated with ASC.

There are limitations in our study. Similar to other retrospective studies using large administrative database, our results demonstrate the clinical characteristics of CRC in California, but they may not represent the patients in other areas. As we did not include patients who were treated non-surgically, our observations are limited to surgically-resected patients. Obviously treatment modality and quality will affect outcomes, although we evaluated the treatment that had been used in these patients, treatment effects could not be fully evaluated and no conclusion on optimal theraputic approach could be elucidated in our study due to data set limitations. Since ASC of colon and rectum is a rare disease, clinical trials are not available to help determine optimal management strategies. Some previous studies19,20.21 have suggested that a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy directed at the squamous component might be useful; however, the roles of these therapies have not been proven. Also, it is important to note that cause-specific mortality, as assessed in population-based research, is subject to inaccuracy. However, others have shown that in general, cause-specific and relative survival from population-based analyses are valid methodologic approaches.22 Despite these limitations, this study provides a large sample size for evaluation of the outcomes of this rare colon and rectum carcinoma.

In conclusion, ASC of the colon and rectum is observed in a small proportion of colorectal cancers in the population. Compared with AC; 1) ASC is comparable to AC in sex distribution age, race, SES and location of tumor, but presents with more advanced disease and with more poorly differentiated tumors; 2) ASC has lower 5-year survival rate compared with AC and 3) ASC is independently associated with increased overall mortality and CRC-specific mortality and it should be considered as a poor prognostic factor of CRC.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number P30CA062203 from the National Cancer Institute.

Thank you to Dr. Ruihong Luo for participation in article drafting, revisions for critical review and intellectual content of this study.

Footnotes

Contribution of authors: Hossein Masoomi, MD: Data analysis and interpretation, article drafting, final approval of version to be published

Argyrios Ziogas, PhD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, manuscript revision for critical intellectual content, final approval of version to be published

Bruce Lin, MD: Data analysis and interpretation, article drafting, final approval of version to be published

Andy Barleben, MD: Data analysis and interpretation, article drafting, final approval of version to be published

Steven Mills, MD: Data analysis and interpretation, article drafting, final approval of version to be published

Michael J. Stamos, MD: Conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, article drafting and revisions for critical content, final approval of version to be published, project support

Jason Zell, DO, MPH: Conception and design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, article drafting and revisions for critical intellectual content, final approval of version to be published, project support.

This study was presented at the 95th annual meeting of the American College of Surgeon on October 11-15, 2009, Chicago, IL

References

- 1.Juturi JV, Francis B, Koontz PW, Wilkes JD. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the colon responsive to combination chemotherapy: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:102–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02235191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herxheimer G. Uber heterologe cancroid. Beitr Path Anat. 1907;41:348. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cagir B, Nagy MW, Topham A, Rakinic J, Fry RD. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon, rectum, and anus: epidemiology, distribution, and survival characteristics. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:258–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02237138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frizelle FA, Hobday KS, Batts KP, Nelson H. Adenosquamous and squamous carcinoma of the colon and upper rectum: a clinical and histopathologic study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:341–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02234730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Reporting in California: Abstracting and Coding Procedures for Hospitals, in California Cancer Reporting system Standards. 7th. I. California Department of Health Services, Cancer Surveillance Section; 2003. [November 8, 2011]. http://www.ccrcal.org/PDF/Vol-I.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj KP, Taylor TH, Wray C, Stamos MJ, Zell JA. Risk of second primary colorectal cancer among colorectal cancer cases: a population-based analysis. J Carcinog. 2011;17:10–6. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.78114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le H, Ziogas A, Lipkin SM, Zell JA. Effects of socioeconomic status and treatment disparities in colorectal cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1950–62. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wray CM, Ziogas A, Hinojosa MW, Le M, Stamos MJ, Zell JA. Tumor subsite location within the colon is prognostic for survival after colon cancer diagnosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1359–66. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a7b7de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [June 11, 2011]; http://www.ccrcal.org/Reports_and_Factsheets/PCNST-09.shtml.

- 10.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, et al. International classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrelli NJ, Valle AA, Weber TK, Rodriguez-Bigas M. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1265–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michelassi F, Mishlove LA, Stipa F, Block GE. Experience at the University of Chicago, review of the literature, report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:228–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02552552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erasmus LJ, van Heerden JA, Dahlin DC. Adenoacanthoma of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21:196–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02586571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kontozoglou TE, Moyana TN. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon—an immunocytochemical and ultrastructural study: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:716–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02555782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerezo L, Alvarez M, Edwards O, Price G. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:597–603. doi: 10.1007/BF02554156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto S, Yoshimura K, Ri S, Fujita S, Akasu T, Moriya Y. The risk of multiple primary malignancies with colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:S30–6. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0600-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comer PT, Beahrs OH, Dockerty MB. Primary squamous cell carcinoma and adenoacanthoma of the colon. Cancer. 1971;28:1111–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1971)28:5<1111::aid-cncr2820280504>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider TA, Birkett DH, Vernava AM. Primary adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7:144–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00360355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leow CK, Chung CC, Lau WY, Li AK. Malignant anal tumors in the Chinese population in Hong Kong. Surg Oncol. 1996;5:65–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(96)80002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michelassi F, Montag AG, Block GE. Adenosquamous-cell carcinoma in ulcerative colitis. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:323–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02554371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarfati D, Blakely T, Pearce N. Measuring cancer survival in populations: relative survival vs cancer-specific survival. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):598–610. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]