Abstract

Objectives

To assess the effect of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age in Ghana on cause- and age-specific infant mortality. In addition, because of recently published studies from Guinea Bissau, effects on infant mortality by sex and season were assessed.

Design

Double-blind, cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting

7 contiguous districts in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana.

Participants

All women of reproductive age (15–45 years) resident in the study area randomised by cluster of residence. All live born infants from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008 followed up through 4-weekly home visits.

Intervention

Weekly low-dose (25 000 IU) vitamin A.

Main outcome measures

Early infant mortality (1–5 months); late infant mortality (6–11 months); infection-specific infant mortality (0–11 months).

Results

1086 clusters, 62 662 live births, 52 574 infant-years and 3268 deaths yielded HRs (95% CIs) comparing weekly vitamin A with placebo: 1.04 (0.88 to 1.05) early infant mortality; 0.99 (0.84 to 1.18) late infant mortality; 1.03 (0.92 to 1.16) infection-specific infant mortality. There was no evidence of modification of the effect of vitamin A supplementation on infant mortality by sex (Wald statistic =0.07, p=0.80) or season (Wald statistic =0.03, p=0.86).

Conclusions

This is the largest analysis of cause of infant deaths from Africa to date. Weekly vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age has no beneficial or deleterious effect on the causes of infant death to age 6 or 12 months in rural Ghana.

Trial registration number

Article summary

Article focus

This paper reports the results of planned (a priori) analyses of the effect of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on cause- and age-specific infant mortality in the ObaapaVitA trial.

In addition, because of the recent interest in potential differential effects, we also assessed effects by sex and season.

Key messages

The analyses from this trial indicate that weekly vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age has no beneficial or deleterious effect on the causes of death in their babies of age 6 or 12 months, no effect on infection-specific infant mortality and no role for inclusion in child survival programs in Asia and Africa.

We also failed to demonstrate any benefit or harm from vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age and in infant males or females in our study population. There was also no modification of the effect of vitamin A supplementation and mortality by season.

Strengths and limitations of this study

There were some limitations to our trial. There was no direct observation of capsule taking; however, adherence was supported by an extensive Information, Education and Communication strategy, and we estimated that on average 75% of women both received and took all four capsules every month.

We also used verbal postmortems (VPMs) and physician coders to assign cause of death, and it was not possible to use health facility records or postmortem examinations to verify the cause of death. Misclassification is common in VPM studies, but this can be minimised when broad categories such as ‘infection’, ‘prematurity’ and ‘asphyxia’ are used. Our VPM tools were also validated in similar study populations, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity were reported in comparison to a gold standard.

Strengths included the fact that our study was large (62 000 infants) prospective and population-based. All resident women in the trial districts and their babies were enrolled, and loss to follow-up was low, even in women with babies who had died.

Introduction

Vitamin A deficiency is a major public health problem. It is most prevalent in young children and pregnant women in low-income countries, especially in Africa and South-East Asia.1 Clinical vitamin A deficiency can manifest as xerophthalmia, blindness and enhanced susceptibility to infections especially measles.2

Vitamin A supplementation in children aged 6–59 months substantially reduces mortality3 4; these effects are apparent for deaths due to diarrhoea and measles but not respiratory infections or malaria.3 5 However, the effect of vitamin A supplementation in children younger than 6 months is less clear. Trials of supplementation of 25 000 international units (IU) vitamin A linked to each of the first three doses of diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis immunisations demonstrated no significant effects on early or late infant mortality.6 Early studies from Guinea Bissau suggested that there may be interaction with the season of birth with higher mortality occurring in the rainy season in neonates who were supplemented with vitamin A.7 8 Findings from two trials in Guinea Bissau also suggested increased mortality among girls, but not among boys, in the second half of infancy following neonatal vitamin A supplementation.7 9 However, a recent meta-analysis involving all trials to date indicated that there is no differential effect of neonatal vitamin A supplementation in boys and girls.10

A recent Cochrane review reported that vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age has no significant effect on maternal or infant outcomes.11 This review included our recently reported findings from the Ghana ObaapaVitA cluster-randomised trial of the impact of weekly low-dose (25 000 IU) vitamin A supplementation given to women of reproductive age, which suggested no beneficial effect on the survival of their babies.12 However, there have been no reports of the effect of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on cause-specific infant mortality or on mortality in early and late infancy. These outcomes were not included in our initial publication due to space limitations.

This paper reports the results of planned (a priori) analyses of the effect of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on cause- and age-specific infant mortality in the ObaapaVitA trial. We hypothesised that vitamin A supplementation would have significant effects on all three groups (neonatal, early infant and late infant mortality). In addition, because of the recent interest in potential differential effects, we also assessed effects by sex and season.

Methods

Methods are reported in detail elsewhere,12 and the full protocol is available online (at http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/eph/nphir/research/obaapavita/obaapavita_trial_protocol.pdf). In brief, all women aged 15–45 years living in seven, predominantly rural, districts in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana, who were able to give informed consent and who planned to live in the trial area for at least 3 months were eligible for enrolment. Enrolment started in December 2000 and continued throughout the trial; fieldworkers recruited eligible women who migrated into their areas and girls who became fifteen. The trial ended in September 2008, with data collection continuing through October 2008. Verbal postmortems (VPMs) to ascertain cause of death were implemented for all infant deaths from June 2003. Analyses in this paper are therefore based on all live births that took place to study participants between June 2003 and September 2008.

There are two distinct seasons in the study area. October–March is the dry season with high temperatures (mean 30°C) and low rainfall (mean 100 mm). April–September is the rainy season with lower temperatures (mean 26°C) and high rainfall (mean 1270 mm).13

Intervention

Women were randomised, according to their cluster of residence, to receive either weekly vitamin capsules, containing 25 000 IU (7500 μg) of vitamin A in soybean oil in a dark red opaque soft gel, or identical-looking placebo capsules containing only soybean oil. The vitamin A dose was selected to deliver the recommended dietary allowance while being safe during pregnancy.14 15 The capsules were manufactured by Accucaps Industries Limited, Windsor, Ontario, Canada; the vitamin A was donated by Roche. Women were visited at home every 4 weeks, and given four capsules to be taken over the next 4 weeks. Adherence was supported by an extensive Information, Education and Communication programme, based on formative research conducted before the trial began.16

Randomisation and blinding

The trial area was divided into clusters of compounds, with fieldworkers responsible for a fieldwork area (FWA) of four contiguous clusters, visiting women in one cluster per week over a 4-weekly cycle. There were a total of 272 FWAs and 1086 clusters. Randomisation was by cluster with two clusters in each FWA allocated to vitamin A and two to placebo to ensure geographic matching of vitamin A and control groups. A computer-generated randomisation list was prepared for the capsule manufacturers by an independent statistician. The capsules were packaged in labelled jars, for each cluster for each week of the trial. No trial personnel (participants, careproviders, data collectors, data analysts, investigators) had access to the randomisation list or to any information that would allow them to deduce or change the cluster allocation.

Data collection

Fieldworkers collected data during 4-weekly home visits on pregnancies, births, deaths, migrations, socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women and number of capsules taken since the last visit. From June 2003, field supervisors conducted VPMs with close relatives or friends for all deaths reported among infants born to trial women; these included an open history, plus questions on signs, symptoms and the illness that lead to death. Standard WHO VPM tools and methods were used.17 The methods have been presented and validated in earlier papers.18–20 VPMs were reviewed by two experienced doctors, who independently assigned a single primary cause of death using identical tools. If the coders disagreed, the form was independently reviewed by a third doctor and a consensus coding accepted if two of the three agreed. If there was no consensus, the three coders met to determine whether they could reach agreement. The cause of death classification system had six major categories: congenital abnormalities, prematurity, birth asphyxia, infection (subdivided into neonatal, diarrhoea, pneumonia, malaria, measles, other), other specific cause of death and unexplained cause of death.

Sample size

Sample size for the trial was determined by the rarest outcome, pregnancy-related mortality, to allow for the detection of a reduction of 33% in pregnancy-related mortality in the vitamin A arm, with 90% power and at 5% significance, and allowing for a 10% design effect. The sample size of 62 000 infants was also sufficient to detect at least a 15% effect of vitamin A supplementation on neonatal, early infant and late infant mortality.

Statistical methods

Stata V.10.0 was used for all analyses. Infant mortality (deaths from 0 to 11 months of age), early infant mortality (deaths from 1 to 5 months of age) and late infant mortality (deaths from 6 to 11 months of age) were all expressed per 1000 infant-years of follow-up. Neonatal mortality (<1 month) was expressed per 1000 live births. Intention-to-treat analyses compared treatment groups using logistic regression for neonatal mortality and Cox regression for infant mortality. Random-effects regression (for logistic regression) or robust standard errors (for Cox regression) were used to take account of the clustered design. The proportional hazards assumption for all Cox regressions was assessed using visual inspection of the Nelson–Aalen log cumulative hazard curves. Interaction between vitamin A supplementation and season or gender was examined using the likelihood ratio test (when using logistic regression) or the Wald test (when using Cox regression).

Intention to treat was by cluster of residence. As previously described,12 we accounted for the fact that vitamin A stores require some time to become replete or depleted by excluding the first 6 months of follow-up after recruitment or after any change of treatment group for the same reasons, and regarding women as belonging to their pre-move group for a period of 2 months after changing group. Infants were considered as belonging to the treatment arm of the mother at the time of delivery.

Trial monitoring and ethical approval

The conduct of the trial was overseen by Trial Steering and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committees. It was approved by the ethics committees of the Ghana Health Service and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and registered with http://clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00211341). Full informed consent was obtained from all trial participants.

Results

Participant flow

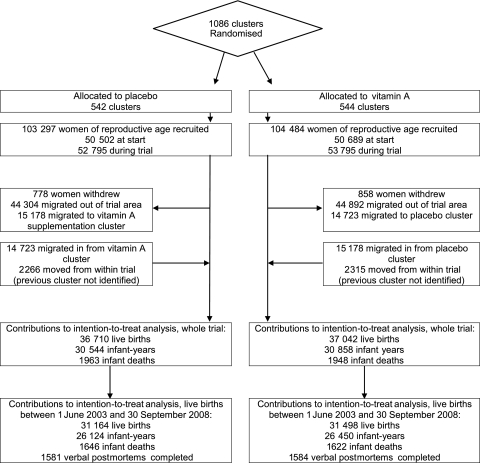

The trial profile is shown in figure 1. One thousand and eighty-six clusters (542 placebo, 544 vitamin A) in 272 FWAs were randomised. Recruitment, withdrawals and migration patterns were similar in the vitamin A and placebo arms, as were socio-demographic characteristics (table 1). There were a total of 62 662 live births to 50 422 women of reproductive age in the trial from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008 with 52 574 infant-years of follow-up and 3268 infant deaths (figure 1). For babies born before 31 October 2007, follow-up to 1 year was 86%. Data collection for the trial ended on 31 October 2008, and 90% of the babies born after 31 October 2007 were seen in the last month of data collection or had died before then.

Figure 1.

Profile of trial and subjects included in analysis of all live births from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008.

Table 1.

Comparability of vitamin A and placebo groups, all live births from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008

| Characteristic | Placebo, n (%*) | Vitamin A, n (%*) |

| Live births in study population (n) | 31 164 (100) | 31 498 (100) |

| Age group at the birth outcome, years | ||

| <20 | 2404 (8) | 2536 (8) |

| 20–24 | 7645 (25) | 7747 (25) |

| 25–29 | 8866 (28) | 8993 (29) |

| 30–34 | 6848 (22) | 6818 (22) |

| 35–39 | 3784 (12) | 3752 (12) |

| ≥40 | 1617 (5) | 1652 (5) |

| Previous live births (n) | ||

| 0 | 3463 (11) | 3628 (12) |

| 1 | 6032 (19) | 6061 (19) |

| 2 | 5812 (19) | 5719 (18) |

| 3 | 4628 (15) | 4888 (15) |

| 4 | 3664 (12) | 3714 (12) |

| 5+ | 7217 (23) | 7179 (23) |

| Not known | 348 (1) | 309 (1) |

| Highest educational level | ||

| None | 12 142 (39) | 12 280 (39) |

| Primary school | 5812 (19) | 5865 (19) |

| Secondary school | 12 515 (40) | 12 636 (40) |

| Technical college or university | 262 (1) | 281 (1) |

| Not known | 433 (1) | 436 (1) |

| Religion | ||

| Christian | 20 663 (66) | 20 721 (66) |

| Muslim | 7428 (24) | 7594 (24) |

| Traditional African | 1718 (6) | 1803 (6) |

| Other | 939 (3) | 961 (3) |

| Not known | 416 (1) | 419 (1) |

| Ethnic group | ||

| Akan | 13 361 (43) | 13 693 (43) |

| Other | 17 392 (56) | 17 386 (55) |

| Missing | 411 (1) | 419 (1) |

| Wealth quintiles | ||

| 1st (poorest) | 8039 (26) | 8339 (26) |

| 2nd | 6743 (22) | 6666 (21) |

| 3rd | 5668 (18) | 5768 (18) |

| 4th | 5177 (17) | 5171 (16) |

| 5th (richest) | 4618 (15) | 4670 (15) |

| Not known | 919 (3) | 884 (3) |

Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Age at death

Overall, 58.9% (1925/3268) of the deaths occurred in the neonatal period, 21.3% (699/3268) occurred in early infancy (1–5 months) and 19.7% (644/3268) occurred in late infancy (6–11 months) (table 2). Mortality was comparable for the vitamin A and placebo groups during the neonatal period and in early and late infancy (table 3).

Table 2.

Mortality by age and sex for infants born from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008

| Overall | Males* | Females* | |

| Neonatal deaths | |||

| Live births (n) | 62 662 | 31 631 | 30 980 |

| Total neonatal deaths | 1925 | 1113 | 790 |

| Total neonatal deaths/1000 live births | 30.72 | 35.19 | 25.50 |

| OR (95% CI) | – | 1.00 | 0.72 (0.65 to 0.79) |

| p Value | – | – | <0.0001 |

| Infant deaths 1–5 months | |||

| Infant years of follow-up 1–5 months | 23 660 | 11 886 | 11 772 |

| Total 1–5 months deaths | 699 | 362 | 334 |

| Total 1–5 months deaths/1000 infant-years | 29.54 | 30.46 | 28.37 |

| HR (95% CI) | – | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.08) |

| p Value | – | – | 0.35 |

| Infant deaths 6–11 months | |||

| Infant years of follow-up 6–11 months | 24 094 | 12 087 | 12 005 |

| Total 6–11 months deaths | 644 | 352 | 292 |

| Total 6–11 months deaths/1000 infant-years | 26.73 | 29.12 | 24.32 |

| HR (95% CI) | – | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.98) |

| p Value | – | – | 0.02 |

Sex of baby unknown in 51 of 62 662 infants.

Table 3.

Effect of maternal weekly vitamin A supplementation on infant deaths by age and sex; intention-to-treat analyses, all live births from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008 (n=62 662)

| Both sexes combined |

Males* |

Females* |

||||

| Placebo | Vitamin A | Placebo | Vitamin A | Placebo | Vitamin A | |

| Neonatal deaths | ||||||

| Live births (n) | 31 164 | 31 498 | 15 777 | 15 854 | 15 357 | 15 623 |

| Total neonatal deaths | 984 | 941 | 589 | 524 | 382 | 408 |

| Total neonatal deaths/1000 infant-years | 31.57 | 29.87 | 37.33 | 33.05 | 24.87 | 26.12 |

| Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.78 to 1.00) | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.22) |

| p Value | – | 0.26 | – | 0.05 | – | 0.49 |

| Infant deaths 1–5 months | ||||||

| Infant years of follow-up 1–5 months | 11 796 | 11 936 | 5921 | 5965 | 5839 | 5934 |

| Total 1–5 months deaths | 341 | 358 | 166 | 196 | 174 | 160 |

| Total 1–5 months deaths/1000 infant-years | 28.91 | 29.99 | 28.04 | 32.86 | 29.80 | 26.97 |

| Adjusted HR† (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.22) | 1.00 | 1.17 (0.95 to 1.45) | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.14) |

| p Value | – | 0.65 | – | 0.15 | – | 0.39 |

| Infant deaths 6–11 months | ||||||

| Infant years of follow-up 6–11 months | 12 004 | 12 161 | 6022 | 6065 | 5945 | 6060 |

| Total 6–11 months deaths | 321 | 323 | 170 | 182 | 151 | 141 |

| Total 6–11 months deaths/1000 infant-years | 26.74 | 26.56 | 28.23 | 30.01 | 25.40 | 23.27 |

| Adjusted HR† (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.84 to 1.18) | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.33) | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.73 to 1.16) |

| p Value | – | 0.94 | – | 0.59 | – | 0.46 |

p Value for interaction between vitamin A and sex for neonatal deaths =0.06 (Likelihood ratio statistic =3.48).

p Value for interaction between vitamin A and sex for infant deaths 1–5 months =0.10 (Wald statistic =2.75).

p Value for interaction between vitamin A and sex for infant deaths 6–11 months =0.33 (Wald statistic =0.96).

Sex of baby unknown in 51 of 62 662 infants.

Adjusted for clustering by ObaapaVitA cluster of residence.

Cause of death

A suitable respondent was found for the administration of 3129 VPMs out of the total 3268 deaths (95.7%). Coders were able to assign a cause for 2589 of these deaths (82.7%). Causes of death were markedly different in the neonatal (table 4) and postneonatal periods (1–11 months) (table 5). Asphyxia was coded as the most common cause of neonatal death (37.0%; 568/1536), followed by infection (28.8%; 442/1536) and prematurity (18.3%; 281/1536). In contrast, infection was coded as the cause of 94.2% (992/1053) of the postneonatal deaths; 30% (298/992) of these infection deaths were due to pneumonia, 22.9% (228/992) to malaria, 14.1% (140/992) to diarrhoea, 0.6% (6/992) to measles and 32.3% (320/992) were due to other infection (meningitis, tetanus, HIV/AIDS or infection with an unknown cause).

Table 4.

Effect of weekly vitamin A supplementation on neonatal deaths by cause of death; intention-to-treat analyses, all live births from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008

| Placebo | Vitamin A | |

| All live births (n) | 31 164 | 31 498 |

| Total neonatal deaths | 984 | 941 |

| Infection | ||

| Infection-specific deaths (n) | 218 | 224 |

| Infection-specific deaths/1000 live births | 7.00 | 7.11 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.23) |

| p Value | – | 0.86 |

| Prematurity | ||

| Prematurity-specific deaths (n) | 149 | 132 |

| Prematurity-specific deaths/1000 live births | 4.78 | 4.19 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.14) |

| p Value | – | 0.33 |

| Asphyxia | ||

| Asphyxia-specific deaths (n) | 284 | 284 |

| Asphyxia-specific deaths/1000 live births | 9.11 | 9.02 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.19) |

| p Value | – | 0.95 |

| Other deaths† | ||

| Other deaths (n) | 128 | 117 |

| Other specific deaths/1000 live births | 4.11 | 3.71 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.17) |

| p Value | – | 0.41 |

| Unexplained | ||

| Unexplained deaths (n) | 175 | 156 |

| Unexplained deaths/1000 live births | 5.62 | 4.95 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.71 to 1.10) |

| p Value | – | 0.26 |

| Cause of death not ascertained | ||

| Unascertained deaths (n) | 30 | 28 |

| Unascertained deaths/1000 live births | 0.96 | 0.89 |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.55) |

| p Value | – | 0.76 |

Adjusted for clustering by ObaapaVitA cluster of residence.

Includes congenital abnormality, accident or injury, malignant tumours and neonatal jaundice.

Table 5.

Effect of weekly vitamin A supplementation on postneonatal deaths by cause of death; intention-to-treat analyses, all live births from 1 June 2003 to 30 September 2008

| Placebo | Vitamin A | |

| Infant-years of follow-up | 23 800 | 24 097 |

| Total postneonatal deaths | 662 | 681 |

| Infection | ||

| Infection-specific deaths (n) | 479 | 503 |

| Infection-specific deaths/1000 child-years | 20.13 | 20.87 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.90 to 1.19) |

| p Value | – | 0.61 |

| Pneumonia | ||

| Pneumonia-specific deaths (n) | 152 | 146 |

| Pneumonia-specific deaths/1000 child-years | 6.39 | 6.06 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.21) |

| p Value | – | 0.67 |

| Malaria | ||

| Malaria-specific deaths (n) | 115 | 113 |

| Malaria-specific deaths/1000 child-years | 4.83 | 4.69 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.74 to 1.27) |

| p Value | – | 0.83 |

| Diarrhoea | ||

| Diarrhoea-specific deaths (n) | 60 | 70 |

| Diarrhoea-specific deaths/1000 child-years | 2.52 | 2.90 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.62) |

| p Value | – | 0.42 |

| Measles | ||

| Measles-specific deaths (n) | 4 | 2 |

| Measles-specific deaths/1000 child-years | 0.17 | 0.08 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.49 (0.09 to 2.69) |

| p Value | – | 0.41 |

| Other infection† | ||

| Other infection deaths (n) | 148 | 172 |

| Other infection-specific deaths/1000 child-years | 6.22 | 7.14 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.91 to 1.45) |

| p Value | – | 0.24 |

| Other deaths‡ | ||

| Other deaths (n) | 42 | 29 |

| Other deaths/1000 child-years | 1.76 | 1.20 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.42 to 1.10) |

| p Value | – | 0.12 |

| Unexplained | ||

| Unexplained deaths (n) | 106 | 103 |

| Unexplained deaths/1000 child years | 4.45 | 4.27 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.27) |

| p Value | – | 0.78 |

| Cause of death not ascertained | ||

| Unascertained deaths (n) | 35 | 46 |

| Unascertained deaths/1000 child years | 1.47 | 1.91 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.30 (0.84 to 2.00) |

| p Value | – | 0.24 |

Adjusted for clustering by ObaapaVitA cluster of residence.

Includes meningitis, tetanus, HIV/AIDS or infection with an unknown cause.

Includes congenital abnormality, accident or injury and malignant tumours.

The distributions of both neonatal and postneonatal causes of death were similar in the placebo and vitamin A groups (tables 4 and 5). There was no marked impact of vitamin A supplementation on any specific cause of mortality, either in the neonatal period (table 4) or in the postneonatal period (table 5). The overall HR for infection-specific infant mortality was 1.03 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.16).

Sex

Mortality rates were considerably lower for females than males during the neonatal period and late infancy (table 2). Mortality was also lower in females than males in the early infant period, but this difference was marginal and non-significant. Mortality rates were similar for the vitamin A and placebo groups for both males and females in the neonatal period and early and late infancy. There was also no evidence of modification of the effect of vitamin A supplementation on infant mortality by sex (Wald statistic =0.07, p=0.80).

Season

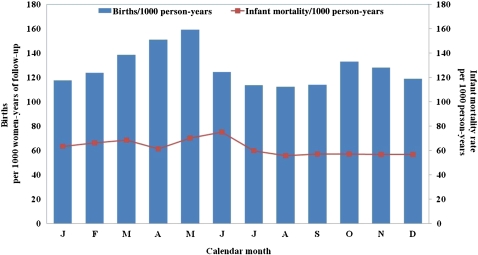

There was no obvious seasonality in mortality rates (figure 2). Fifty-three per cent (1729/3268) of infant deaths occurred in the rainy season (April–September) and 47% (1539/3268) in the dry season (October–March). Mortality rates were similar in both (HR 0.99 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.06), p=0.67), and there was no impact of vitamin A supplementation on infant deaths in either the rainy (HR 0.98 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.08), p=0.68) or the dry season (HR 0.97 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.08), p=0.56). There was also no evidence of modification of the effect of vitamin A supplementation on infant mortality by season (Wald statistic =0.03, p=0.86).

Figure 2.

Births and infant mortality per 1000 person-years, by calendar month.

Discussion

This large-scale community-based trial provides the largest analysis of cause of infant deaths from Africa to date. Our analyses indicate that weekly vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age has no beneficial or deleterious effect on the causes of death in their babies of age 6 or 12 months in rural Ghana.

We identified no other published studies of the effect of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on cause-specific infant mortality. In particular, no cause-specific data have been reported from the other two trials of maternal vitamin A supplementation in Nepal21 and Bangladesh.22 23 Studies of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation have also not reported effects on cause-specific infant mortality.24 25 The biological action of vitamin A and previous evidence from childhood vitamin A trials5 26 led us to postulate a priori that vitamin A may have an effect on deaths due to infant infection. However, we found no effect of vitamin A on deaths due to infant infections in our study population. It was also possible that vitamin A could have had an effect on deaths due to prematurity-related complications (eg, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotising enterocolitis, intraventricular haemorrhage) as vitamin A has effects on epithelial integrity, cellular differentiation and foetal surfactant synthesis.2 27 However, we found no impact of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on prematurity-specific neonatal mortality.

The absence of an impact on early or late infant survival concurs with the findings of trials of maternal vitamin A supplementation from Nepal21 and Bangladesh22 23 and a pooled meta-analysis of the effects of maternal multiple micronutrient supplements.24 25 The results also concur with those of our main paper, which reported no effects of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on maternal mortality and stillbirths.12 However, none of these trials presented data separately for males and females. We recorded lower mortality rates in females than males throughout infancy and markedly so during the neonatal period and late infancy. We found no evidence of any differential effect of vitamin A supplementation in boys or girls, or by season. This is in contrast to the recent Guinea Bissau trials which indicated that there may be an interaction between neonatal vitamin A supplementation and childhood immunisations by age, sex and season.7 9

There were some limitations to our trial. There was no direct observation of capsule taking; however, adherence was supported by an extensive Information, Education and Communication strategy, and we estimated that on average 75% of women both received and took all four capsules every month.12 We also used VPMs and physician coders to assign cause of death, and it was not possible to use health facility records or postmortem examinations to verify the cause of death. Misclassification is common in VPM studies, but this can be minimised when broad categories such as ‘infection’, ‘prematurity’ and ‘asphyxia’ are used.17 19 Our VPM tools were also validated in similar study populations, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity were reported in comparison to a gold standard.17 18 20 In addition, our study was prospective and population based. All resident women in the trial districts and their babies were enrolled, and loss to follow-up was low, even in women with babies who had died.

Our findings have important implications for policy and program development. They indicate that vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age will not reduce infection-specific infant mortality, has no influence on any of the other causes of death in their infants and is not an effective strategy to improve neonatal or infant survival. It also appears that vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age has no role in reducing overall or cause-specific infant mortality in child survival programs. We also failed to demonstrate any harm from vitamin A supplementation in infant males or females in our study population. These findings add to the ongoing debate about the safety of vitamin A supplementation and whether vitamin A supplementation may have differential effects on mortality in boys and girls in early and late infancy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the verbal post mortem coders and their coordinators, Dr Bilal Iqbal Avan, Dr Poorna Gunasekera, Dr Kwame Darko and Dr Seyi Soremekun, the support of the chiefs, elders and opinion leaders in the trial area and the substantial contribution of all women who participated. We thank all staff at Kintampo Health Research Centre involved in the trial, especially site leaders, coordinators, supervisors, fieldworkers, data managers, data supervisors, data entry clerks and administrative support staff. We also thank the trial steering committee and data monitoring and ethics committee for their ongoing support and guidance. Finally, we acknowledge the substantial contribution of the late Dr Paul Arthur the founding director of Kintampo Health Research Centre and one of the principal investigators for this trial.

Footnotes

To cite: Edmond K, Hurt L, Fenty J, et al. Effect of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on cause-specific early and late infant mortality in rural Ghana: ObaapaVitA double-blind, cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000658. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000658

Funding: This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries; the views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. In addition, United States Agency for International Development contributed some funding to the initial stages of the trial, and Roche kindly donated the vitamin A palmitate for the capsules. The researchers are fully independent from the funders. The study funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and we declare that all authors have no financial or non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by Kintampo Health Research Centre, Ghana Health Service, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Contributors: The paper was drafted by KE, LH and BRK and reviewed by all authors. The late Paul Arthur, BRK and OC designed the study. KE, LH, AHAtA and SO-A were responsible for trial conduct. ZH and CT participated in design and management of the Information, Education and Communication component of the trial. SA-E, SD, BRK, CH and JF participated in design and management of the data management system. CZ coordinated the fieldwork. LH, CH and JF undertook the statistical analyses. BRK is the guarantor for the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.WHO Global Prevalence of Vitamin A Deficiency in Populations at Risk 1995–2005. WHO Global Database on Vitamin A Deficiency. Geneva: WHO, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.West KP., Jr Vitamin A deficiency disorders in children and women. Food Nutr Bull 2003;24(4 Suppl):S78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaton GH, Martorell R, Aronson KJ, et al. Effectiveness of vitamin A supplementation in the control of young child morbidity and mortality in developing countries Policy discussion paper no 13. Geneva: United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committee on Nutrition, 1993:1–120 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imdad A, Herzer K, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Vitamin A supplementation for preventing morbidity and mortality in children from 6 months to 5 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(12):CD008524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous. Potential interventions for the prevention of childhood pneumonia in developing countries: a meta-analysis of data from field trials to assess the impact of vitamin A supplementation on pneumonia morbidity and mortality. The Vitamin A and Pneumonia Working Group. Bull World Health Organ 1995;73:609–19 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anonymous. Randomised trial to assess benefits and safety of vitamin A supplementation linked to immunisation in early infancy. WHO/CHD Immunisation-linked vitamin A supplementation study group. Lancet 1998;352:1257–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benn CS, Diness BR, Roth A, et al. Effect of 50,000 IU vitamin A given with BCG vaccine on mortality in infants in Guinea-Bissau: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2008;336:1416–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisker AB, Lisse IM, Aaby P, et al. Effect of vitamin A supplementation with BCG vaccine at birth on vitamin A status at 6 wk and 4 mo of age. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1032–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benn CS, Fisker AB, Napirna BM, et al. Vitamin A supplementation and BCG vaccination at birth in low birthweight neonates: two by two factorial randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkwood B, Humphrey J, Moulton L, et al. Neonatal vitamin A supplementation and infant survival. Lancet 2010;376:1643–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Broek N, Dou L, Othman M, et al. Vitamin A supplementation during pregnancy for maternal and newborn outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(11):CD008666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkwood BR, Hurt L, Amenga-Etego S, et al. Effect of vitamin A supplementation in women of reproductive age on maternal survival in Ghana (ObaapaVitA): a cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:1640–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF Macro Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Accra, Ghana: GSS, GHS, and ICF Macro, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.IVACG Statement: Safe Doses of Vitamin A During Pregnancy and Lactation. Washington: IVACG, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Safe Vitamin A Dosage During Pregnancy and Lactation: Recommendations and Report of a Consultation. Geneva, CH: WHO, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill Z, Kirkwood B, Kendall C, et al. Factors that affect the adoption and maintenance of weekly vitamin A supplementation among women in Ghana. Public Health Nutr 2007;10:827–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Verbal Autopsy Standards: Ascertaining and Attributing Cause of Death. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalter HD, Gray RH, Black RE, et al. Validation of postmortem interviews to ascertain selected causes of death in children. Int J Epidemiol 1990;19:380–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edmond KM, Quigley MA, Zandoh C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of verbal autopsies in ascertaining the causes of stillbirths and neonatal deaths in rural Ghana. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2008;22:417–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quigley MA, Armstrong Schellenberg JR, Snow RW. Algorithms for verbal autopsies: a validation study in Kenyan children. Bull World Health Organ 1996;74:147–54 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz J, West KP, Jr, Khatry SK, et al. Maternal low-dose vitamin A or beta-carotene supplementation has no effect on fetal loss and early infant mortality: a randomized cluster trial in Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:1570–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christian PWKJ, Labrique A, Klemm R, et al. Effects of maternal vitamin A or beta-carotene supplementation on maternal and infant mortality in rural Bangladesh: the JIVITA-1 trial. Proceedings of the Micronutrient Forum; 16-18 April 2007. Turkey: IVACG, 2007:129 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemm RD, Labrique AB, Christian P, et al. Newborn vitamin A supplementation reduced infant mortality in rural Bangladesh. Pediatrics 2008;122:e242–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronsmans C, Fisher DJ, Osmond C, et al. ; Maternal Micronutrient Supplementation Study Group Multiple micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy in low-income countries: a meta-analysis of effects on stillbirths and on early and late neonatal mortality. Food Nutr Bull 2009;30(4 Suppl):S547–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shankar AH, Jahari AB, Sebayang SK, et al. ; The Supplementation with Multiple Micronutrients Intervention Trial (SUMMIT) Study Group Effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant death in Indonesia: a double-blind cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371:215–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaton GH, L'Abbé MR, et al. Effectiveness of vitamin A supplementation in the control of young child morbidity and mortality in developing countries. Nutrition policy Discussion Paper No. 13. Geneva: UN, ACC/SCN State-of-the-art Series, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephensen CB. Vitamin A, infection, and immune function. Annu Rev Nutr 2001;21:167–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.