Abstract

Aim

To characterize the histologic and cellular response to A. actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) infection.

Material and Methods

Wistar rats infected with Aa were evaluated for antibody response, oral Aa colonization, loss of attachment, PMN recruitment, TNF-α in the junctional epithelium and connective tissue, osteoclasts, and adaptive immune response in local lymph nodes at baseline and 4, 5 or 6 weeks after infection. Some groups were given antibacterial treatment at 4 weeks.

Results

An antibody response against Aa occurred within 4 weeks of infection and 78% of inoculated rats had detectable Aa in the oral cavity (p<0.05). Aa infection significantly increased loss of attachment which was reversed by antibacterial treatment (p<0.05). TNF-α expression in the junctional epithelium followed the same pattern. Aa stimulated high osteoclast formation and TNF-α expression in the connective tissue (p<0.05). PMN recruitment significantly increased after Aa infection (p<0.05). Aa also increased the number of CD8+ T cells (p<0.05) but not CD4+ T cells or regulatory T cells (Tregs) (p>0.05).

Conclusion

Aa infection stimulated a local response which increased numbers of PMNs and TNF-α expression in the junctional epithelium and loss of attachment. Both TNF-a expression in JE and loss of attachment was reversed by antibiotic treatment. Aa infection also increased TNF-α in the connective tissue, osteoclast numbers, CD8+ T cells in lymph nodes. The results link Aa infection with important characteristics of periodontal destruction.

Keywords: A.actinomycetemcomitans, periodontal disease, bone resorption, host-pathogen interactions, disease models, animals

INTRODUCTION

Localized aggressive periodontitis (LAgP), previously known as localized juvenile periodontitis, is characterized by relatively rapid and severe destruction of periodontal tissues affecting the first molars and central incisors, which is usually detected and diagnosed during puberty in systemically healthy individuals (Armitage & Cullinan 2010). This form of periodontitis presents minimal signs of clinical inflammation and plaque build-up (Armitage & Cullinan 2010). It is more frequently seen in subjects of African descent (Löe & Brown 1991, Brown et al. 1996, Fine et al. 2007) and is usually found in other family members (Tonetti & Mombelli 1999, van Winkelhoff & Slots 2005). The primary suspected pathogen associated with this form of periodontal disease is A. actinomycetemcomitans (Aa).

Aa is a gram-negative non-motile bacterium that is indigenous to the oral cavity (Henderson et al. 2010) that is also associated with endocarditis (Paturel et al. 2004). Many studies have shown high levels of Aa in samples obtained from subjects with localized aggressive periodontitis compared to periodontally healthy, gingivitis and subjects with other forms of periodontal disease (Slots et al. 1980, Hamlet et al. 2001, Suda et al. 2003, Haubek et al. 2008). After periodontal treatment a reduction in Aa is consistent with clinical improvement (Christersson et al. 1985, Mandell & Socransky 1988, Takamatsu et al. 1999) and the presence of Aa can be an indicative of future disease progression (Fine et al. 2007). It is estimated that 90% of patients diagnosed with LAgP and 10–20% healthy subjects harbor Aa (Hamlet et al. 2001, Darout et al. 2002, Suda et al. 2003). The oral mucosa has been identified as an initial colonization site and primary reservoir (Rudney et al. 2005). Aa is also able to colonize tooth surfaces and the subgingival space, where it may lead to disease progression (Fine et al. 2005, Rudney et al. 2005, Fine et al. 2007).

Recently, a new animal model has been developed to study the effects of Aa colonization on periodontal disease progression (Fine et al. 2001, Schreiner et al. 2003, Li et al. 2010, Schreiner et al. 2011). This model consists of infecting rats with the rough strain of Aa, known to adhere to different surfaces, including the buccal epithelial and teeth (Fine et al. 2001, 2002). This model has provided knowledge on how the adaptive immune response is regulated (Li et al. 2010). It is also well suited to examine aspects of bacterial behavior that promote colonization and initiation of periodontal disease (Graves et al. 2008). Previous studies have utilized different strains of rats and more recently it has been established that different patterns of infection and bone loss can be found between rat strains (Schreiner et al. 2011). However, the local impact of Aa in this animal model has not previously been examined at the histological or cellular level. Thus the aim of this study was to characterize the local and systemic response to the Aa infection in the Wistar rat to better understand the consequences of periodontal bone loss due to bacterial challenge by analyzing the response at the histologic and cellular level.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals

The rat model has been previously described (Schreiner et al. 2003). Briefly, forty-four Wistar rats (16–20 weeks of age) were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA), housed in separate cages and fed powdered food (Laboratory Rodent Meal Diet 5001, Purina Mills Feeds, St Louis, MO). To depress the `natural' resident flora, rats received in their water a daily dose of kanamycin (20 mg) and ampicillin (20 mg) for 4 days. During the last 2 days of antibiotic treatment, the oral cavities of the rats were swabbed with a 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse (Peridex, Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH). After a subsequent period of 3 days without antibiotic treatment, the rats were divided into five groups of approximately 7 rats each. The adherent Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) strain, Columbia University Aa clinical isolate #1,000 (CU1000NRif) (N = nalidixic acid resistant; rif = rifampicin resistant) was grown in A. actinomycetemcomitans growth medium containing rifampicin (35 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as described (Schreiner et al, 2011) for 2 days at 37°C in a 10% CO2/90% air atmosphere. After fasting for 3 hours, rats received 108 Aa cells in in 1g of powdered food supplemented with 3% sucrose in PBS placed in special feeder trays (1ml). This protocol was followed for 8 days (Schreiner et al. 2003). During the first 4 days of the feeding protocol the animals also received 108 Aa cells in 1ml of inoculation solution by oral gavage. After 1 hour the inoculated food was removed and replaced with regular powdered food. After the feeding protocol was over the animals were euthanized four, five and six weeks later. Baseline animals did not undergo antibacterial treatment and were not inoculated with Aa but did receive powered food supplemented with 3% sucrose under the same conditions as experimental rats. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibacterial treatment post-feeding

Four weeks after Aa inoculation 2 groups of animals, with approximately 7 rats each, received a daily dose of kanamycin (20 mg) and ampicillin (20 mg) in the water for 4 days with the intention to stop the infection. Concomitantly, the oral cavities of these rats were swabbed with a 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse (Peridex, Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH). These animals were euthanized 1 and 2 weeks after the start of the antibacterial regimen.

Sampling of rat oral microflora

Two microbial samples were collected, one after the inoculation of Aa and the other at the time of euthanasia. The rats were anaesthetized and their oral microflora was sampled with a cotton tip swab for soft tissue sampling, and a toothpick (Johnson & Johnson, Piscataway, NJ) for hard tissue sampling. Both samples were combined in tubes containing 1 ml PBS. Serial ten-fold dilutions were made and plated on trypticase soy agar (TSA) with 5% sheep blood (BD biosciences, San Jose, CA) for total anaerobe counts. Trypticase soy agar plates were incubated in an anaerobic atmosphere at 37°C for 7 days to obtain total bacterial counts. To determine whether Aa colonized the oral cavities of inoculated rats bacterial DNA was isolated from the collected oral samples with a DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and subjected to PCR analysis. Forward and reverse primers (5'-GGAATTCCTAGGTATTGCGAAACAATTTGATC-3' and 5'-GGAATTCCTGAAATTAAGCTGGTAATC-3', respectively) amplified a 262-base-pair PCR product from the Aa leukotoxin gene as previously described (Goncharoff et al. 1993).

Level of Antibody to Aa

IgG antibody reactive with Aa was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and serum was obtained and stored at −20°C. An Aa lysate was prepared and used to coat the wells of microtiter dishes (NUNCImmunoPlate with Maxi Sorp surface, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY). A standard curve was generated using purified rat IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Rat serum diluted 1/5 and 1/10 in blocking buffer was added to the wells coated with the Aa pellet lysate. The serum dilutions were added, in duplicate. The microtiter plates were covered and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature, and the wells were washed, incubated with rabbit anti-rat IgG-Fc conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) and quantified with p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). After incubation for 1 hour, the absorbance of the microplate wells was read on a microplate reader at 405 nm.

Rats were considered to have been positive for Aa infection if PCR results showed the Aa leukotoxin band or if antibody levels were equal to or greater than twice the mean baseline levels. Animals were considered to be not-infected even if they had been exposed to Aa if both PCR results for Aa leukotoxin and antibody levels were negative. For time course analysis only infected animals were included.

Histomorphometry

Right maxillae were collected at euthanasia, hemi-sected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 48 hours at 4°C with the solution changed twice a day. After 48 hours specimens were washed with PBS and placed in 10% EDTA (pH 7.0) for decalcification. Paraffin-embedded sagittal sections were prepared at a thickness of 5 microns and the interproximal areas between the 1st and 2nd and the 2nd and 3rd maxillary molars were examined. The mid-interproximal region was examined in each specimen and was established by sections where the root canal systems were clearly visible. Two randomly chosen sections of each interproximal area were examined at 200× magnification. All data were analyzed by a blinded examiner who did not know the group to which an animal belonged. The examiner was calibrated against a second individual. Attachment loss was measured by the distance between the cemento-enamel junction and the most coronal extent of connective tissue attachment to cementum. Millimeter was the measurement unit selected for this analysis. Local inflammatory response in the gingival epithelium was evaluated by counting the number of polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells per area at 600× magnification.

Osteoclasts

Osteoclasts were recognized as positive tartate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining on large multinucleated cells directly lining the bone surface in Howship's lacunae. Osteoclast numbers were determined by quantifying number of osteoclasts per mm of bone surface. Since rat molars undergo distal drift (Moss-Salentijn & Moss 1977), there is constant resorptive activity on the proximal bone between the molars. Therefore, the analysis of TRAP-stained sections was restricted to the distal aspect of the interproximal bone. After quantification of osteoclasts two categories were determined. Animals were categorized as having high osteoclast numbers, if the number of osteoclasts was greater or equal to 2, and low osteoclast number if there was 1 or 0 osteoclasts present. Percentage of high and low osteoclast numbers were calculated for statistical analysis.

TNF-α

To evaluate cells that expressed TNF- α in the gingiva epithelium or junctional epithelium (JE), sections were examined by immunohistochemistry with an antibody against TNF-α (IHCWORLD, Woodstock, MD) and examined at 600× magnification. Immunoreactivity was judged by the following scale: 0, no positive cells; 1, three to four positive cells per field with weak immunostaining; 2, four to ten positive cells per field with strong immunostaining; and 3, more than 10 positive cells per field with strong immunostaining.

Systemic leukocyte response

Rat lymph node cells were prepared and analyzed as described (Li et al. 2010). Briefly, at day 0 and after animals had been infected with Aa (4, 5 or 6 weeks) single-cell suspensions were obtained from the submandibular and cervical lymph nodes of the rats. Lymphocyte populations were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. Flow cytometry was conducted on unfractionated lymphocytes. FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR) was used to analyze the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) data. Anti-CD32 (clone D34–485), for blocking FcγII receptor, was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Anti-IA [major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, clone 14-4-4S] antibody obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) was fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated by us. FITC labeled anti-CD4 (clone OX35), anti-CD3 (clone G4.18), and PE labeled anti-CD4 (clone OX38) were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). FITC labeled anti-FoxP3 (clone FJK-16s), PE labeled anti-CD25 (clone OX39) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For hematologic analysis 1 ml of blood was collected from each rat at time of euthanasia into tubes with EDTA (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Blood was analyzed by HemaTrue Hematology Analyzer (HESKA, Loveland, CO).

Statistical Analysis

Fisher's exact test was applied to compare the percentage of animals which were positive or negative for Aa in baseline and after exposure to Aa. The same statistical test was applied to compare specimens with high osteoclast numbers between baseline and 4, 5 and 6 weeks after Aa infection. Pearson's chi-squared test was applied to compare the percentage of animals with a positive or negative antibody threshold to Aa before or after the second antibacterial treatment. This same test was also applied to compare osteoclast numbers between rats with or without antibacterial treatment following Aa infection. The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare antibody titers against Aa in animals treated or not with antibiotics plus chlorhexidine after Aa infection. Median values, instead of mean values, were used for the analysis of total anaerobe counts since outlier values were left in the data set. The median test was then applied to compare total anaerobe counts at baseline to 4, 5 and 6 week time points, Aa-infected and non-infected rats, as well as in rats with or without antibacterial treatment following Aa infection. A two-tailed T-test was used to compare lymphocyte populations and leukocyte populations from peripheral blood between Aa-infected and non-infected rats; LOA, PMNs and levels of TNF-α in junctional epithelium and gingiva between Aa-infected and non-infected rats and animals treated or not with antibiotics plus chlorhexidine after Aa infection. A one-way ANOVA test with contrast was used to compare LOA and PMNs between baseline and 4, 5 and 6 week infection time points. Significance levels were set at 5%.

RESULTS

Aa colonization

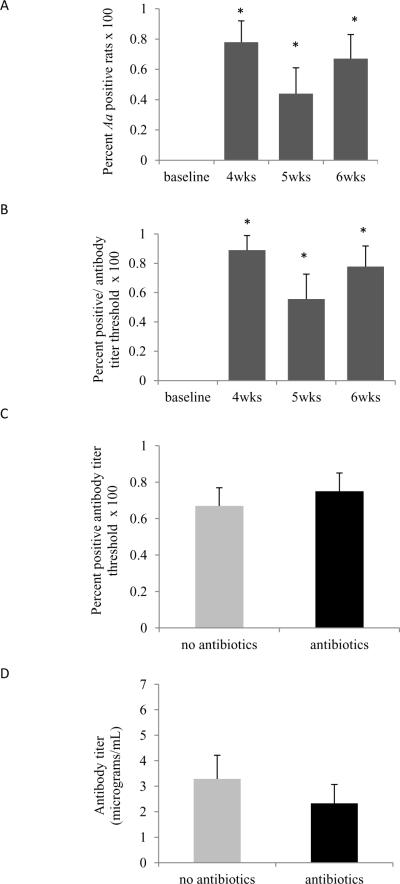

To establish whether animals exposed to Aa were infected samples were assessed from soft and hard tissue of the oral cavities at the time of euthanasia. The bacterial colonies tested positive for Aa by leukotoxin-specific PCR. No Aa was observed in rats not inoculated with Aa. Following inoculation 78% of the rats had detectable Aa in the oral cavity by PCR at the 4-week time point compared to no animals at baseline (p<0.05) (Fig.1A).

Figure 1. Aa infection and Anti-Aa antibody levels.

(A) Swabs were obtained from the oral epithelium and tooth surface and examined for the presence of Aa. The percent Aa positive animals following inoculation at baseline and at 4, 5 and 6 weeks post-inoculation. Significance was determined by Fisher's exact test (B). The percent rats with anti-Aa IgG levels at least two fold higher than the mean baseline level at baseline or 4, 5 and 6 weeks after inoculation was determined by ELISA. Significance was determined by Fisher's exact test. (C) Percent rats with antibody titers at least two fold higher than the mean baseline level with or without antibiotic plus chlorhexidine treatment following Aa inoculation. Significance was determined by Pearson Chi-square test. (D) Anti-Aa IgG levels in serum collected from Aa-inoculated animals with or without anti-bacterial treatment. Significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney test. The data are represented as mean ± SEM. * p<0.05

Antibody titer and threshold

Antibody levels against Aa were assessed in pre- and post-infected animals. Four weeks after Aa inoculation, over 80% of the rats had positive antibody titers defined as values two fold higher than baseline (p<0.05) (Fig.1B). When comparing animals which received antibacterial treatment to those without such treatment no change was observed in percent antibody threshold levels (Fig.1C) or antibody titer (p>0.05) (Fig.1D).

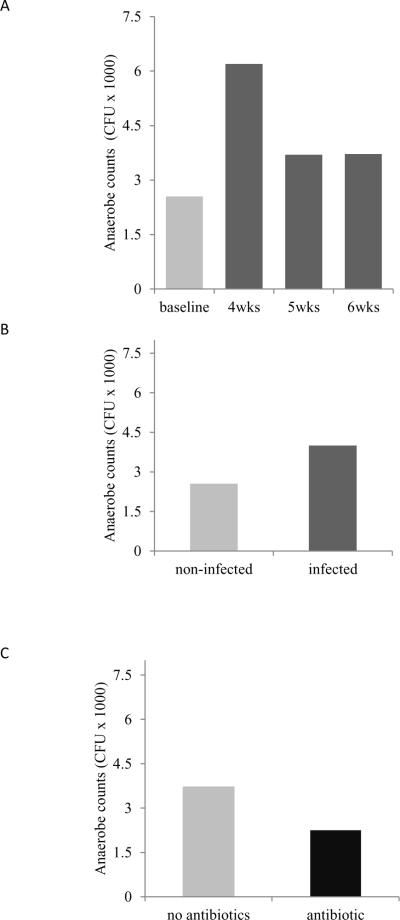

Total anaerobe bacteria counts

Using samples collected from the oral cavity, total anaerobe bacterial counts were evaluated before and after Aa inoculation (Fig.2A–C). No statistical significant differences were observed in any of the evaluated comparisons (p>0.05).

Figure 2. Total anaerobe counts.

Total anaerobe counts were obtained prior to and at different time points after infection with Aa. (A) Number of CFU at baseline and following inoculation with Aa. (B) Total anaerobe counts from not-infected and Aa-infected rats. (C) Total anaerobe counts from Aa-fed animals with antibacterial treatment (p>0.05). Data are presented as median; the median test was used for statistical significance. None of the values were significant (p>0.05).

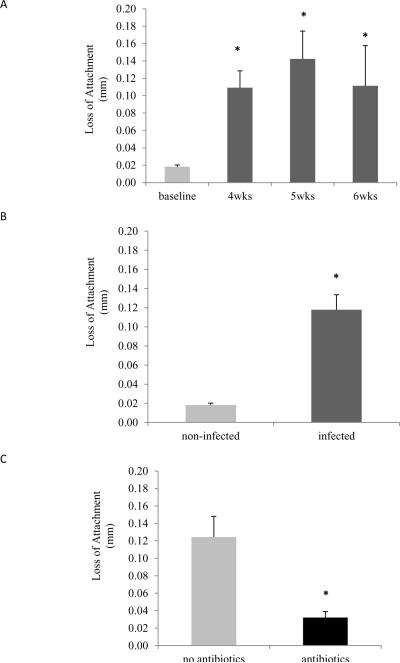

Loss of attachment after Aa inoculation

Loss of attachment (LOA) was measured histologically. Following inoculation with Aa a significant LOA was observed in all experimental time points compared to baseline (p<0.05) (Fig.3A, Supplemental Figure 1). When considering Aa infected animals as a group, a 6-fold increase in LOA was found (p<0.05) (Fig. 3B). Antibacterial treatment promoted a reduction in LOA compared to the untreated group (p<0.05) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Loss of attachment.

Loss of attachment (LOA) was measured by the distance between the cemento-enamel junction and the most coronal extent of connective tissue attachment to cementum. (A) LOA in not-infected (baseline) animals and Aa-infected animals at 4, 5 and 6 weeks. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. (B) LOA in not-infected and Aa-infected animals. Significance was determined by Student's t-test. (C) LOA in Aa-infected animals treated or not with antibiotics plus chlorhexidine. Significance was determined by Student's t-test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p<0.05

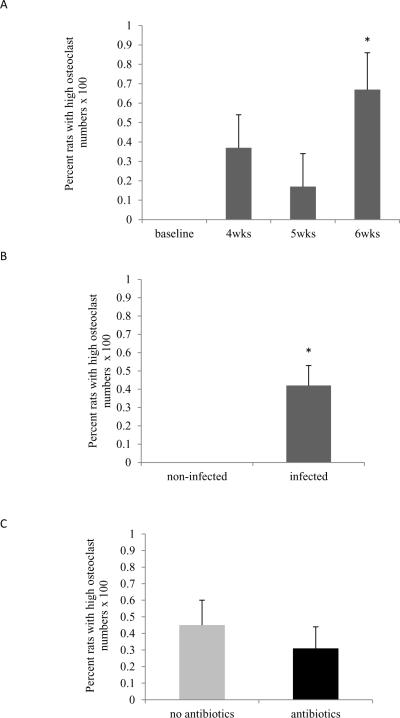

Osteoclast numbers post Aa infection

The impact of Aa infection on osteoclast formation was examined as the percent rats with high osteoclast numbers, which had the highest levels at six weeks following Aa infection (p<0.05) (Fig.4A, Supplemental Figure 2). As a group, 52% of animals had high numbers of osteoclasts after Aa inoculation compared to none in animals that had not been infected with Aa (p<0.05) (Fig.4B). Antibacterial treatment did not affect the percent of rats that had high numbers of osteoclasts compared to untreated animals in the time frame tested (Fig.4C).

Figure 4. Osteoclasts.

Osteoclasts were recognized as TRAP positive, multinucleated cells directly lining the bone surface. (A) Percent rats with high osteoclasts numbers in not-infected (baseline) animals and Aa-infected animals at 4, 5 and 6 weeks. Significance was determined by Fisher's exact test. (B) Percent rats with high osteoclast numbers in not-infected and Aa-infected animals. Significance was determined by Fisher's exact test. (C) Percent rats with high osteoclast numbers in Aa-infected animals with or without antibacterial treatment. Significance was determined by Chi-square test. * p<0.05

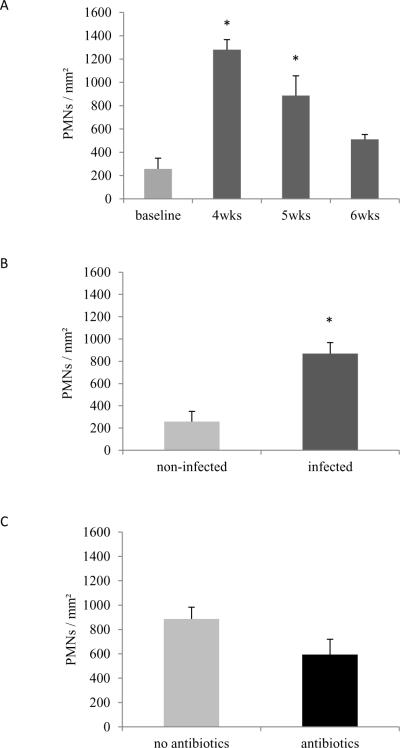

Inflammatory response to Aa infection

Local inflammatory response was evaluated by both counting the number of PMNs in the gingival epithelium as well as by TNF-α expression in the gingival epithelium and JE. PMN numbers increased at 3 to 4 fold after A.a. infection (p<0.01) (Fig. 5A, Supplemental Figure 3) while the 6 week and time point showed no significant difference compared to baseline (p>0.05). When considering Aa infected animals as a group there was a 3.4-fold increase in the number of PMNs/mm2 after infection (p<0.004) (Fig. 5B). Antibiotics administration post-infection did not significantly reduce the number of PMNs in the epithelium (P>0.05) (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Polymorphonuclear (PMNs) leukocytes in gingival epithelium.

PMNs were counted in HE stained sections at 1000× magnification and presented as number of PMNs per mm2. (A) Number of PMNs/mm2 in non-infected (baseline) animals versus Aa-infected animals at 4, 5 and 6 weeks. Significance was determined by One-way ANOVA test. (B) Number of PMNs/mm2 in non-infected and Aa-infected animals. Significance determined by Student's t test. (C) Number of PMNs/mm2 in Aa-infected animals treated or not with antibiotics plus chlorhexidine. Significance determined by Student's t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p<0.05

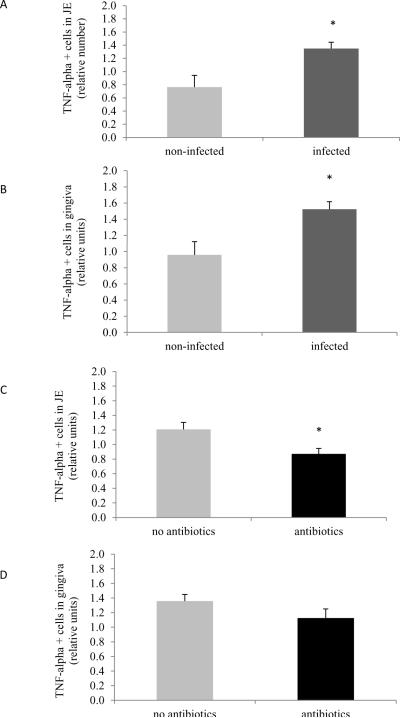

When Aa inoculated animals were examined as group there was a 1.6-fold increase in TNF- α positive cells in the JE compared to not-infected animals (p<0.05) (Fig.6A, Supplemental Figure 4). A similar increase was found in the gingiva of infected animals (1.5-fold) (p<0.05) (Fig.6B). Antibacterial treatment promoted a significant 25% decrease in the number of cells producing TNF- α in the JE (p<0.05) (Fig.6C). In contrast, antibacterial treatment did not affect the number of TNF-α expressing cells in the gingiva (Fig.6D).

Figure 6. TNF-α positive cells in junctional epithelium and gingival connective tissue.

TNF-α immunopositive cells were examined by immunohistochemistry and assessed using the following scale at 600× magnification: 0, no positive cells; 1, three to four positive cells per field with weak immunostaining; 2, four to ten positive cells per field with strong immunostaining; and 3, more than 10 positive cells per field with strong immunostaining. (A) TNF-α positive cells in JE in non-infected and Aa-infected animals. (B) TNF-α positive cells in JE in Aa-infected animals treated or not with antibiotics plus chlorhexidine. (C) TNF-α positive cells in gingival connective tissue of non-infected and Aa-infected animals. (D) Number of TNF- α positive cells in gingival connective tissue of Aa-infected animals treated or not with antibiotics plus chlorhexidine. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined by Student's t-test. * p<0.05

Systemic response

Leukocyte populations in lymph nodes and blood were examined as a measure of the systemic response. No significant differences were observed in B cell activation (MHC II) and CD4+ T cell numbers in the infected animals compared to non-infected animals (Table 1). However, CD8+ T cell numbers showed a 1.6-fold increase after Aa inoculation which was significant (p<0.05). No change in activation of regulatory T (Tregs) cells (CD4+CD25+ and CD4+FoxP3+) was observed in infected animals compared to non-infected (p>0.05). Blood collected at time of euthanasia was analyzed for major leukocyte populations (Table 2). Total white blood cells (WBC), lymphocytes and granulocytes or their percentage did not change after Aa infection (Table 2). Monocyte number and percent exhibited a small but significant decrease compared to non-infected rats (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Lymphocyte populations obtained from draining cervical and submandibular lymph nodes of Aa-infected and non-infected rats

| MHC II (% cells) | CD4+ (% cells) | CD8+ (% cells) | CD4+CD25+ (% cells) | CD4+FoxP3+ (% cells) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-infected (n=4) | 51 ± 4.5 | 36.1 ± 4.8 | 22.6 ± 4.1 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| Infected (n=9) | 48.3 ± 2.6 | 33.3 ± 1.9 | 36 ± 2 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| Fold difference | 0.95 | 0.92 | 1.59* | 1.42 | 1.07 |

p<0.01, compared to non-infected rats.

Table 2.

White blood cells from peripheral blood of Aa-infected and non-infected rats

| WBC (103UI/mL) | LYMP (103UI/mL) | MONO (103UI/mL) | GRAN (103UI/mL) | LYMP (%) | MONO (%) | GRAN (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-infected (n=5) | 7.9 ± 1.3 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 0.06 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 77 ± 2.4 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 18.1 ± 2.1 |

| Infected (n=12) | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 77.2 ± 3.3 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 19.6 ± 3.1 |

| Fold difference | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.75* | 1.08 | 1.0 | 0.67* | 1.08 |

WBC, white blood cells; LYMP, lymphocytes; MONO, monocytes; GRAN, granulocytes.

p=0.02, compared to non-infected rats.

DISCUSSION

Localized aggressive periodontitis is known for its rapid and severe destruction of periodontal tissues and is thought to involve infection by Aa (Schenkein et al. 2007, Armitage & Cullinan 2010). Studies evaluating a periodontal disease rat model with Aa inoculated in the food have shown that Aa infection reliably produces bone loss (Schreiner et al. 2003, Li et al. 2010, Schreiner et al. 2011). However, local histologic changes and hematologic examination of peripheral lymphoid compartments have not been evaluated in this model nor has the effect of antibacterial treatment after infection been examined.

In the present study, we evaluated several parameters of the local host response in the rat periodontium to Aa infection. Loss of attachment after Aa inoculation was evident within 4 weeks and was 6 times greater than loss of attachment in non-infected animals. Loss of attachment was also reversed following antibacterial treatment suggesting that attachment levels in the short term can experience both loss and gain. The number of PMNs in the junctional and gingival epithelium increased with Aa infection. The number of TNF-α expressing cells also increased with Aa infection.

To examine the effect of reversing the infection we examined TNF-α expression in the JE and LOA after antibiotic treatment. It is striking that treatment with antibiotic resulted a significant decrease in the number of epithelial cells expressing TNF-α, which coincided with a gain in attachment. Thus, changes in attachment levels may reflect the expression of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α in the junctional epithelium. TNF-α could potentially prevent reattachment by suppressing the activity of cells needed to produce attachment or by the induction of lytic enzymes that breakdown proteins involved (Smith et al. 2009). Studies have shown that increased levels of TNF-α in the gingival crevicular fluid and periodontal tissues are correlated with periodontitis in humans (Cochran 2008, Graves 2008, Liu et al. 2010).

The generation of osteoclasts was increased with Aa infection but was not significantly impacted by antibacterial treatment. However, this may be due to the relatively short time frame examined after antibacterial treatment, 1 to 2 weeks.

In the study by Schreiner et al. (2011) different rat strains exhibited different rates of colonization by Aa. Some animals were more prone to infection than others, which ranged from 83% in Fawn Hooded Hypertensive rats to 33.3%, in Dahl Salt-sensitive rats, and 17% in Brown Norway rats. Wistar rats have not been previously evaluated in this model. We found that approximately 78% of Wistar rats exposed to Aa became infected as determined by PCR or cultural detection of Aa in bacterial samples. The results indicate that the Wistar rat strain is highly susceptible to Aa colonization using this infection model. Moreover, these rats developed positive antibody titers within four weeks of inoculation. In previous studies (Schreiner et al. 2003; Li et al. 2010; Schreiner et al. 2011) high antibody levels were observed within 12 weeks after inoculation but earlier time points were not examined. It should be noted that in the present study the animals also received the inoculum by oral gavage during the first week of the feeding protocol, providing a greater exposure to the pathogen compared to the original feeding protocol (Schreiner et al. 2003).

Oral bacteria can stimulate cells of the adaptive immune response by increased numbers of activated T- and B-lymphocytes in the periodontal tissues (Graves et al. 2008). We observed an increase in CD8+ T cells in lymphocytes obtained from local draining cervical and submandibular lymph nodes of Aa-infected rats, compared to control rats. Gingival CD8+ T cells have been implicated in gingivitis, chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis (Sigusch et al. 2006, Artese et al., 2011, Lima et al. 2011). The fact that we observed an increase in CD8+ T cells in local draining lymph nodes of Aa-fed rats, suggests an adaptive response to Aa which induced cytotoxic T cells. Changes in the percent CD4+CD25+ T cells in lymph nodes from Aa-infected rats just missed significance compared to control rats (p=0.1). CD25+CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor are regulatory T cells (Treg cells) that prevent a hyperactive adaptive immune response (Sakaguchi 2005) and may be associated with periodontal disease and its attenuation (Nakajima et al. 2005, Cardoso et al. 2008, Garlet et al. 2010). We did not find a change in Treg cells with Aa infection, which may be due to the length of the experiment, four to six weeks (Li et al. 2010). In mice, Tregs have been shown to be upregulated in approximately 9 weeks after Aa inoculation (Garlet et al. 2010). Hematologic examination of blood of Aa-infected rats revealed a significant increase (p<0.05) in both monocyte percentage of WBCs and absolute numbers of monocytes. Although intriguing the systemic changes noted do not necessarily reflect changes that are occurring in the periodontal tissue.

In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that outbred Wistar rats constitute a useful rodent model for studying Aa-induced periodontal disease our studies provide evidence that Aa-infection induces a CD8+ T cell response in draining lymph nodes and an increase in peripheral blood monocytes. Moreover we found that Aa infection induced TNF-α expression in junctional epithelial cells and caused a loss of connective tissue attachment. Significantly both were reversed by antibiotic treatment linking TNF-α expression in epithelial cells to this process providing insight into mechanisms of periodontal disease. Whether or not this particular animal model represents specific processes found in localized aggressive periodontitis remains to be proven.

Supplementary Material

Clinical relevance.

Scientific rationale for the study

The local cellular events through which Aa infection leads to periodontitis have not been investigated by quantitative histologic analysis in the present animal model. Since Aa is an important periodontal pathogen in localized juvenile periodontitis the results give insight into the cellular events modulated by Aa.

Principal findings

Aa infection altered the local response within the periodontium including the induction of cytokine expression, gingival inflammation and loss of attachment in conjunction with alveolar bone loss.

Practical implications

The Aa model is an important tool in understanding the pathogenesis of periodontitis in part because it is a natural host for Aa. The findings provide important characterization of the model that will give insight into human periodontitis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIDCR, DE017732 and DE018307. We would like to thank Harleen Gill for assistance with analysis of histologic specimens and Sunitha Batchu in help preparing the manuscript.

sources of funding This study was supported by grants from the NIDCR (DE017732 and DE018307). Author BBB was the recipient of a scholarship from the CAPES Foundation in Brazil.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare they have no conflict of interests.

References

- Armitage GC, Cullinan MP. Comparison of the clinical features of chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Periodontology 2000. 2010;53:12–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artese L, Simon MJ, Piattelli A, Ferrari DS, Cardoso LA, Faveri M, Onuma T, Piccirilli M, Perrotti V, Shibli JA. Immunohistochemical analysis of inflammatory infiltrate in aggressive and chronic periodontitis: a comparative study. Clinical Oral Investigation. 2011;15:233–240. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0374-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos MF, Lima JA, Vieira PM, Mestnik MJ, Faveri M, Duarte PM. TNF-alpha and Il-4 levels in generalized aggressive periodontitis subjects. Oral Diseases. 2009;15:82–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belibasakis GN, Johansson A, Wang Y, Chen C, Kalfas S, Lerner UH. The cytolethal distending toxin induces receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand expression in human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament cells. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:342–351. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.342-351.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce BF, Xing L. Biology of RANK, RANKL, and osteoprotegerin. Arthritis Research Therapy. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/ar2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LJ, Albandar JM, Brunelle JA, Loe H. Early-onset periodontitis: progression of attachment loss during 6 years. Journal of Periodontology. 1996;67:968–975. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso CR, Garlet GP, Moreira AP, Junior WM, Rossi MA, Silva JS. Characterization of CD4+CD25+ natural regulatory T cells in the inflammatory infiltrate of human chronic periodontitis. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;84:311–318. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christersson LA, Slots J, Rosling BG, Genco RJ. Microbiological and clinical effects of surgical treatment of localized juvenile periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 1985;12:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran DL. Inflammation and bone loss in periodontal disease. Journal of Periodontology. 2008;79(Suppl 8):1569–1576. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damek-Poprawa M, Haris M, Volgina A, Korostoff J, Dirienzo JM. Cytolethal distending toxin damages the oral epithelium of gingival explants. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90:874–879. doi: 10.1177/0022034511403743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darout IA, Albandar JM, Skaug N, Ali RW. Salivary microbiota levels in relation to periodontal status, experience of caries and miswak use in Sudanese adults. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2002;29:411–420. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Furgang D. Lactoferrin iron levels affect attachment of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to buccal epithelial cells. Journal of Periodontology. 2002;73:616–623. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.6.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Goncharoff P, Schreiner H, Chang KM, Furgang D, Figurski D. Colonization and persistence of rough and smooth colony variants of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the mouths of rats. Archives of Oral Biology. 2001;46:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(01)00067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Markowitz K, Furgang D, Fairlie K, Ferrandiz J, Nasri C, McKiernan M, Gunsolley J. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and its relationship to initiation of localized aggressive periodontitis: longitudinal cohort study of initially healthy adolescents. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45:3859–3869. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00653-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Velliyagounder K, Furgang D, Kaplan JB. The Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans autotransporter adhesin Aae exhibits specificity for buccal epithelial cells from humans and old world primates. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:1947–1953. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1947-1953.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Hiroshi I, Sekino S, Numabe Y. Correlations between pentrazin 3 or cytokine levels in gingival crevicular fluid and clinical parameters of chronic periodontitis. Odontology. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10266-011-0042-1. [ahead of print] doi: 10.1007/s10266-011-0042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlet GP, Cardoso CR, Mariano FS, Claudino M, de Assis GF, Campanelli AP, Avila-Campos MJ, Silva JS. Regulatory T cells attenuate experimental periodontitis progression in mice. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2010;37:591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharoff P, Figurski DH, Stevens RH, Fine DH. Identification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: polymerase chain reaction amplification of lktA-specific sequences. Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 1993;8:105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves D. Cytokines that promote periodontal tissue destruction. Journal of Periodontology. 2008;79:1585–1591. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves DT, Cochran D. The contribution of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor to periodontal tissue destruction. Journal of Periodontology. 2003;74:391–401. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves DT, Fine D, Teng YT, Van Dyke TE, Hajishengallis G. The use of rodent models to investigate host-bacteria interactions related to periodontal diseases. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2008;35:89–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves DT, Oskoui M, Volejnikova S, Naguib G, Cai S, Desta T, Kakouras A, Jiang Y. Tumor necrosis factor modulates fibroblast apoptosis, PMN recruitment, and osteoclast formation in response to P. gingivalis infection. Journal of Dental Research. 2001;80:1875–1879. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlet SM, Cullinan MP, Westerman B, Lindeman M, Bird PS, Palmer J, Seymour GJ. Distribution of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia in an Australian population. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2001;28:1163–1171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.281212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubek D, Ennibi OK, Poulsen K, Vaeth M, Poulsen S, Kilian M. Risk of aggressive periodontitis in adolescent carriers of the JP2 clone of Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans in Morocco: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2008;371:237–242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60135-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B, Ward JM, Ready D. Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans: a triple A* periodontopathogen? Periodontology 2000. 2010;54:78–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinadasa RN, Bloom SE, Weiss RS, Duhamel GE. Cytolethal distending toxin: a conserved bacterial genotoxin that blocks cell cycle progression, leading to apoptosis of a broad range of mammalian cell lineages. Microbiology. 2011;157:1851–1875. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.049536-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelk P, Johansson A, Claesson R, Hanstrom L, Kalfas S. Caspase 1 involvement in human monocyte lysis induced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71:4448–4455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4448-4455.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtis B, Tuter G, Serdar M, Akdemir P, Uygur C, Firatli E, Bal B. Gingival crevicular fluid levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology. 2005;76:1849–1855. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang NP, Bartold PM, Cullinan M, Jeffcoat M, Mombelli A, Murakami S, Page R, Papapanou P, Tonetti M, Van Dyke T. Consensus Report: Aggressive Periodontitis. Annals of Periodontology. 1999;4:53. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Messina C, Bendaoud M, Fine DH, Schreiner H, Tsiagbe VK. Adaptive immune response in osteoclastic bone resorption induced by orally administered Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in a rat model of periodontal disease. Molecular Oral Microbiology. 2010;25:275–292. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima PM, Souza PE, Costa JE, Gomez RS, Gollob KJ, Dutra WO. Aggressive and chronic periodontitis correlate with distinct cellular sources of key immunoregulatory cytokines. Journal of Periodontology. 2011;82:86–95. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Bal HS, Desta T, Krothapalli N, Alyassi M, Luan Q, Graves DT. Diabetes enhances periodontal bone loss through enhanced resorption and diminished bone formation. Journal of Dental Research. 2006;85:510–514. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löe H, Brown LJ. Early onset periodontitis in the United States of America. Journal of Periodontology. 1991;62:608–616. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.10.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell RL, Socransky SS. Microbiological and clinical effects of surgery plus doxycycline on juvenile periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology. 1988;59:373–379. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.6.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Salentijn L, Moss ML. Effects of occlusal attrition and continuous eruption on odontometry of rat molars. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1977;47:403–407. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330470310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Ueki-Maruyama K, Oda T, Ohsawa Y, Ito H, Seymour GJ, Yamazaki K. Regulatory T-cells infiltrate periodontal disease tissues. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:639–643. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara M, Oswald E, Sugai M. Cytolethal distending toxin: a bacterial bullet targeted to nucleus. Journal of Biochemistry. 2004;136:409–413. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okui T, Ito H, Honda T, Amanuma R, Yoshie H, Yamazaki K. Characterization of CD4+ FOXP3+ T-cell clones established from chronic inflammatory lesions. Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 2008;23:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paturel L, Casalta JP, Habib G, Nezri M, Raoult D. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans endocarditis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2004;10:98–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo A, Paolillo R, Guida L, Annunziata M, Bevilacqua N, Tufano MA. Effect of metronidazole and modulation of cytokine production on human periodontal ligament cells. International Immunopharmachology. 2010;10:744–750. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudney JD, Chen R, Sedgewick GJ. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Tannerella forsythensis are components of a polymicrobial intracellular flora within human buccal cells. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:59–63. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nature Immunonoly. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner H, Markowitz K, Miryalkar M, Moore D, Diehl S, Fine DH. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-induced bone loss and antibody response in three rat strains. Journal of Periodontology. 2011;82:142–150. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner HC, Sinatra K, Kaplan JB, Furgang D, Kachlany SC, Planet PJ, Perez BA, Figurski DH, Fine DH. Tight-adherence genes of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans are required for virulence in a rat model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2003;100:7295–7300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1237223100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkein HA, Barbour SE, Tew JG. Cytokines and inflammatory factors regulating immunoglobulin production in aggressive periodontitis. Periodontology 2000. 2007;45:113–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annual Reviews of Immunology. 2010;26:421–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenker BJ, Hoffmaster RH, Zekavat A, Yamaguchi N, Lally ET, Demuth DR. Induction of apoptosis in human T cells by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin is a consequence of G2 arrest of the cell cycle. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167:435–441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigusch BW, Wutzler A, Nietzsch T, Glockmann E. Evidence for a specific crevicular lymphocyte profile in aggressive periodontitis. Journal of Periodontal Research. 2006;41:391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva N, Dutzan N, Hernandez M, Dezerega A, Rivera O, Aguillon JC, Aravena O, Lastres P, Pozo P, Vernal R, Gamonal J. Characterization of progressive periodontal lesions in chronic periodontitis patients: levels of chemokines, cytokines, matrix metalloproteinase-13, periodontal pathogens and inflammatory cells. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2008;35:206–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slots J, Reynolds HS, Genco RJ. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease: a cross-sectional microbiological investigation. Infection and Immunity. 1980;29:1013–1020. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.3.1013-1020.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PC, Guerrero J, Tobar N, Cáceres M, González MJ, Martínez J. Tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase production is modulated by epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in human gingival fibroblasts. Journal of Periodontal Research. 2009;44:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda R, Kurihara C, Kurihara M, Sato T, Lai CH, Hasegawa K. Determination of eight selected periodontal pathogens in the subgingival plaque of maxillary first molars in Japanese school children aged 8–11 years. Journal of Periodontal Research. 2003;38:28–35. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu N, Yano K, He T, Umeda M, Ishikawa I. Effect of initial periodontal therapy on the frequency of detecting Bacteroides forsythus, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Journal of Periodontology. 1999;70:574–580. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.6.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng YT, Nguyen H, Gao X, Kong YY, Gorczynski RM, Singh B, Ellen RP, Penninger JM. Functional human T-cell immunity and osteoprotegerin ligand control alveolar bone destruction in periodontal infection. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;106:R59–67. doi: 10.1172/jci10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Annals of Periodontology. 1999;4:39–53. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi N, Kieba IR, Korostoff J, Howard PS, Shenker BJ, Lally ET. Maintenance of oxidative phosphorylation protects cells from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin-induced apoptosis. Cellular Microbiology. 2001;3:811–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.