Abstract

The Children's Play Therapy Instrument (CPTI), its development, and reliability studies are described. The CPTI is a new instrument to examine a child's play activity in individual psychotherapy. Three independent raters used the CPTI to rate eight videotaped play therapy vignettes. Results were compared with the authors' consensual scores from a preliminary study. Generally good to excellent levels of interrater reliability were obtained for the independent raters on intraclass correlation coefficients for ordinal categories of the CPTI. Likewise, kappa levels were acceptable to excellent for nominal categories of the scale. The CPTI holds promise to become a reliable measure of play activity in child psychotherapy. Further research is needed to assess discriminant validity of the CPTI for use as a diagnostic tool and as a measure of process and outcome.(The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 1998; 7:196–207)

The Children's Play Therapy Instrument (CPTI) was constructed to assess the play activity of a child in psychotherapy. It is intended to be of use to clinicians and researchers as an additional criterion for diagnosis—since children with different diagnoses tend to have different forms of play1,2— and as an objective instrument to measure change and outcome in child treatment. The purpose of this article is to describe the instrument and the initial reliability studies.

The CPTI

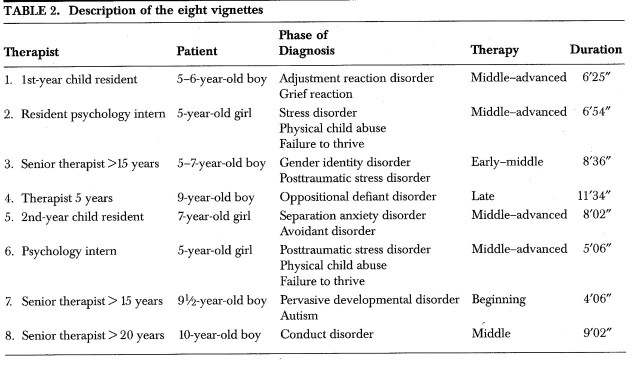

Although several scales have recently been written to measure the play of children,3–5 the CPTI is specifically intended to be a comprehensive measure of a child's play activity in psychotherapy. The CPTI adapts several established scales6–9 in order to measure play activity from a variety of perspectives. The CPTI provides a tool to describe, record, and analyze a child's play activity equivalent to a mental status formulation of a child's overall functioning following a clinical interview. An outline of the CPTI appears in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Level One: Segmentation

Level One analysis addresses the different types of activity the child engages in during the psychotherapy session by segmenting the child's activity into four categories. These four categories are Pre-Play, Play Activity, Non-Play, and Play Interruption. Segmentation of the child's activity results in an overview of the distribution and span of time of various categories of the child's activity in therapy. For example, segmentation delineates a child who does not play from a child who does; it registers the activity of a child who undergoes play interruptions and contrasts it with that of a child who is capable of sustained play activity. It provides information on the ratio between play activity and non-play activity. During the session, clinical experience suggests that a child with significant emotional problems will tend to spend less time engaged in play activity and will experience interruptions due to anxiety or aggression.

Pre-Play is defined as the activity in which the child is “setting the stage” for play. She may pick up a toy and manipulate it, arrange play materials, or try out a character's voice or actions. The predominant purpose of pre-play activity is preparation. Pre-play may be prolonged in compulsive or depressed children. In some instances, the child will not progress beyond pre-play.

Play Activity begins if the child becomes engrossed in playful activity often indicated by the adult or child exhibiting one or a combination of the following behaviors: 1) an expression of intent (e.g., “Let's play.”); 2) actions indicating initiative, such as definition of roles (e.g., “This dolly will be the teacher”; “Let's climb the mountain”); 3) an expression of specific positive or negative affects such as glee, delight, pleasure, surprise, anxiety, fear, disgust, or boredom; 4) focused concentration; 5) use of toy objects or the physical surroundings to develop a narrative.

Normal Play in children is generally an age-appropriate, joyful, absorbing activity. It is initiated spontaneously, with a developing theme carried to a resolution; there is a natural ending and then a move on to another activity. In contrast, pathological play of children with the diagnosis of severe disruptive disorders has been described as compulsive, joyless, and monotonous; the play of autistic children is joyless, nonreciprocal, repetitive, with no evident narrative and no sense of resolution; and the play of psychotic children is characterized by drivenness, sudden fluid transformations of the characters in the play, and play disruption. From the perspective of segmentation, a child optimally involved in play can consistently develop play after pre-play preparation and can unfold a play narrative ending naturally in play satiation.10 If the length of the segments of play is sufficient for the expression of the child's narratives, the patient therapy session is being used optimally and/or the patient has improved in her capacity to play.

Non-Play refers to a variety of activities or behaviors of the child outside the realm of the play activity, such as showing reluctance, eating, reading, doing homework, or conversing with the therapist. All of these activities or behaviors have in common the absence of involvement in play activity and may have positive or negative implications in relation to therapeutic alliance and phase of treatment.

Play Interruption is operationally defined as any abrupt cessation in a play activity—for example, if the child must go to the bathroom or abruptly ends the play activity because of some extraneous distraction. The time interval of 18 to 22 seconds was pragmatically chosen because raters agreed it was a minimum interval that could be reliably timed without instruments.

Once the therapy session has been segmented, a detailed description of one play activity segment, based on the videotape, is written. This constitutes a “play narrative” that includes the setting of the play, relevant dialogue, associated affects, the child's play themes, and the child's attitudes and involvement in the play activity and with the therapist while playing. The play narrative is a central integrating database to which the rater returns when rating any of the individual subscales. The emphasis is on a frame-by-frame analysis integrating all the distinctive features of the child's play activity and concomitant affects.

Level Two: Dimensional Analysis

The Dimensional Analysis examines the play activity segment using three distinct parameters: Descriptive, Structural, and Adaptive.

Descriptive Analysis:

The Descriptive Analysis includes the following subscales: 1) Category of the Play Activity, which lists non–mutually exclusive types of play activity: gross motor activity, construction fantasy, game play; 2) Script Description, which measures the child's initiatives to play, the contribution of the adult to the unfolding of the child's play, and the interaction between child and therapist in composing the play; this subscale provides information regarding the child's autonomy and reciprocity as well as a measure of therapeutic alliance between therapist and child; and 3) Sphere of the Play Activity, which indicates the spatial realms within which the play activity takes place: Autosphere (the realm of the body); Microsphere (the realm of small toys), or Macrosphere (the realm of the actual surroundings).8 This subscale may have specific clinical reference in terms of boundaries, reality testing, maturity, and perspective taking.

Structural Analysis:

The structural analysis includes the following measures of a child's play activity: 1) Affective Components, 2) Cognitive Components, 3) Dynamic Components, and 4) Developmental Components.

Affective Components of Play Activity. The types and range of emotions brought by the child to her play reflect those feelings significant in her own life. The link between emotions and play activity is what brings play alive with understanding. Concentration and involvement characterize play activity. The overall hedonic tone may vary from positive feelings, expressing pleasure, to negative feelings, associated with conflict.8 When distress is too threatening to the child, this will eventuate in play disruption.8 The child's capacity to regulate expression of feelings will affect and/or reflect the organization of play.11 The greater capacity for smooth transitions and regulation of affect reflects an integration of the child's subjective world, and it is a key to the capacity to play at the highest levels of creativity. If the child is able to gain expression of intense feelings through play, she has made giant steps toward coping and mastery. The capacity to play symbolically implies the capacity for regulation of emotions. Indeed, scenarios portrayed with intensity and a wide range of emotions can be assumed to be of great significance to the child.

Cognitive Components of Play Activity. This modified scale was based on the work of Inge Bretherton6 on symbolic play. The structure of the social representational world is a crucial dimension of the child's play. From a cognitive perspective, it indicates the degree to which a child is capable of creating narrative structures to represent different affect-laden relationships. Beginning role-play is the child pretending he is another person, or animating a toy or another's behavior. In its most complex form, role-play becomes directorial play or narrator play, with several interacting roles, enlivened by the child with a variety of emotional themes.

Younger children are capable of only simple representations; older children may draw from a varied repertoire. The level of role representation also indicates progression and regression in the child's level of functioning. If a child is unable to achieve a given complexity of role-play, this may reflect a lack of differentiation between self and others, an incapacity for empathy with and investment in others, or cognitive limitations due to stage of development or other causes.9,12 Further, Piaget13 refers to failure to view reality from different perspectives as a failure in decentering. The child is unrelated to the other person and remains centered on herself in an egocentric fashion. Alternatively, others (including the therapist or toys) may be animated only as recipients or extensions of the child's activities. From this initial point, the child proceeds to playing with therapist and toys as passive recipients and begins to comprehend the give and take of reciprocal roles and their reactions.

A major advance occurs when the child is capable of expressing independent intentionality for a toy or a person. At this important juncture the child has become capable of assuming a different role, other than her own, without experiencing the threat that she herself might disappear. An example of this type of cognitive anxiety occurs on Halloween, when some young children, 3 to 4 years old, exhibit fear of being in disguise. The costume suggests to the young child that she could disappear. However, at a later age a child can tolerate donning a disguise and playing another's role; she has gained self-constancy.

Dynamic Components of Play Activity. The topic of play reveals important emotional themes to the child. A child who repetitively engages in play about particular topics is communicating about the types of conflicts he is dealing with at the time: fear of death, sexual themes, competitiveness. The theme indicates the narrative of the play enacted by particular characters. It is important to keep in mind what topics and themes might be expected for a given developmental perspective and what minor discrepancies might represent divergence from this expected pattern. The divergence may be significant in conveying a specific concern of the child.

The level of relationship portrayed within the play activity specifies the pattern of interactions between play characters. The level of dyadic, triadic, and oedipal configurations places the child at different points of personality organization, from severely disturbed personalities to neurotic or normal ones.

The Quality of Relationship Within the Play Activity segment is an adaptation of the Urist Scale,9 as written for children by Tuber,14 and the scale of Diamond et al.15 It assesses, through the dynamics of the narrative, the nature of the child's emotional conflicts and the extent of expression of aggression—direct, attenuated, neutralized, or sublimated—that he exercises over his subjective world, i.e., autonomous, dependent, and destructive interaction among play characters.

Developmental Components of Play Activity. This dimension compares the child's activity with play of other children of the same age, gender, and level of emotional and social development. This analysis implies an underlying epigenetic sequence to the unfolding of a child's capacity to play. It is a relative judgment and depends on cultural and social standards and values. Because play unfolds in a socially shared context, group norms are appropriate to evaluate the child's play. Ideally, play activity is consistent across developmental dimensions.

Several different sources supplied information for the compilation of these last categories. Gender identity assessment was influenced by the writing of Erikson,8,10,16 Coates,17 and Zucker;18 psychosexual phases were based on the writings of Anna Freud19 and Peller;20 separation-individuation phases were based on the writings of Mahler;21 and the social level of play includes Winnicott's concept of the capacity to play alone.22

Adaptive Analysis:

The adaptive analysis assesses the overall purpose of the play activity for the playing child. The child's observable play behaviors are classified as manifesting specific coping/defensive strategies grouped into four clusters: 1) Normal, 2) Neurotic, 3) Borderline, and 4) Psychotic. These clusters may be placed in sequence in order of their appearance. The concept of a spectrum of clusters of coping and defensive strategies was based on the writings of Vaillant,23 Perry et al.,24 and P. Kernberg.25

A final subscale measures the child's awareness that he is engaged in play activity. This subscale condenses several cognitive and affective variables that determine how capable the child is of observing himself at play, or, alternatively, the extent to which he and his surroundings have been completely absorbed into the play.

As outlined above, each of the CPTI scales (Descriptive, Structural, and Adaptive) consists of several subscales (see Table 1). Depending on the interests of the examiner, he or she may use the CPTI in its entirety or may select only certain scales or combinations of subscales.

Level Three: Patterns Over Time

This level of analysis refers to patterns of the child's activity over time and seeks to assess changes in treatment. The patterns of segmentation are expected to change over time. For example, the sequence and length of the different segments of the child's activity—Pre-play, Play Activity, Non-play, and Interruption—change in the course of treatment depending on the child's diagnosis and type of treatment. However, this level of analysis will not be addressed in this article.

Preliminary Reliability Study

Construction of the instrument required multiple observations of videotaped play therapy sessions. The associated discussions involved 10 experienced clinicians over a span of 3 years. The authors of the scale gleaned material from these discussions to write a manual defining the primary dimensions of the CPTI and formulating operational definitions for each scale and subscale, with clinical illustrations.

Methods and Results

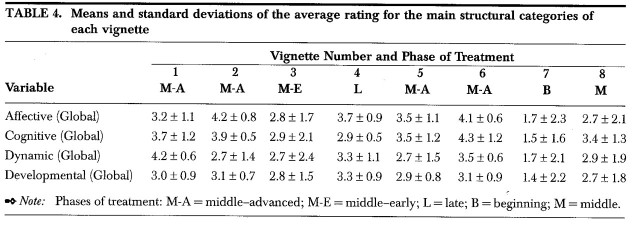

A preliminary reliability study was planned using three members of the group as raters. A videotape montage consisting of eight clinical vignettes was composed by an independent clinician trained to identify the different categories of child activity. The main selection criterion was to find segments that contained at least one segment of play activity and any of the other three child activities (Pre-Play, Non-Play, and Interruption). Table 2 describes the sample.

TABLE 2.

Level One (Segmentation):

The three raters (one psychiatrist, two psychologists) were child therapists, each with more than 10 years of clinical experience. They rated the eight vignettes independently, with subsequent discussions of the ratings to improve on the clarity of the segmentation in the manual.

Agreement on the segmentation of the child's activity into four categories (Pre-Play, Non-Play, Play, and Interruption) as measured by the weighted kappa coefficient was 0.69.26 This level of agreement between the judges on segmentation is considered to be good. (Landis and Koch27 furnished criteria to assess the level of agreement between judges as calculated from the kappa: 0.00 to 0.39 poor; 0.40 to 0.74 acceptable to good; 0.75 to 1.00 excellent.)

Level Two (Dimensional Analysis):

Two raters (one psychiatrist, one psychologist) completed ratings for level two. Analysis of the play activity segments was done by using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)28 for ordinal categories of the CPTI and kappa for the nominal ones. The most consistent subscale scores were obtained on the Descriptive dimension of the CPTI. For example, Category of Play Activity, ICC = 0.68; Script Description, ICC = 0.70; Sphere of Play Activity, ICC = 0.88. (Jones et al.29 suggested 0.70 agreement as an acceptable level when complex coding schemes are used; Gelfand and Hartmann30 recommend 0.60.)

Among the Structural and Adaptive scales, good to excellent scores were obtained for all the subscales on these dimensions. These scores ranged from ICC 0.50 to 0.79. For example, Affects Expressed in Play, ICC = 0.77; Stability of Role Representation, ICC = 0.79; Developmental Level of Play, ICC = 0.50; Social Level of Play, ICC = 0.56. Low scores were obtained on Role Representation, ICC = 0.29; Use of Play Object, ICC = 0.33; and Use of Language, ICC = 0.32. The Adaptive dimension produced the lowest results, ICC = 0.09.

Despite acceptable levels of agreement between raters on many of the subscales, there were disparities on some subscales, which were attributed primarily to the lack of sufficient specificity in definition of categories in the manual. A decision was made to revise the scoring manual and refine the definitions.

To establish a consensual rating to be used as a standard for new independent raters, the raters of the preliminary study performed an item-by-item analysis of the ratings of the eight vignettes.

Reliability Study: Independent Raters and Comparison With Consensus

Methods

Three independent raters, recruited from different institutions, rated the same eight videotaped vignettes used in the preliminary reliability study. The raters were all child psychologists, ranging in experience from 1 to 12 years in child therapy. They received 15 hours of training from one of the authors (a psychologist). The training consisted of group discussions based on definitions and descriptions of the CPTI scales found in the manual.

Eight vignettes were selected from a set of 19 videotaped play therapy sessions by an independent clinician who was trained to identify the different Level One categories of Child's Activity, namely Pre-Play, Play, Non-Play, and Interruption. The main selection criterion was to find segments that contained at least one Play Activity, defined as a narrative with a beginning and an end, and any of the other three Child Activities. Also, the vignettes were chosen to provide a varied array of child diagnoses, levels of therapist experience, and phases of treatment. The duration of the vignettes ranged from 4 minutes, 6 seconds, to 11 minutes, 34 seconds, with a mean of 7 minutes, 47 seconds, and a standard deviation of 2 minutes, 37 seconds (see Table 2).

To maintain each rater's accuracy, ratings sessions were split into two parts, as suggested by Hartmann,31 each part consisting of the CPTI-based rating of four vignettes followed by a discussion with the trainer.

After the submission of the whole ratings, discussion and comparison with the authors' consensus ratings were conducted. Reliability estimates were obtained for the degree of agreement of each individual rater with the consensus. The raters contributed to the clarification of the manual categories and to their training by the exchange of opinions and clinical examples from their own experience.

Three types of reliability estimates were derived from data, according to the different types of scales constituting the CPTI and the number of raters used in the experiment.

Reliability of the categorical data obtained from the segmentation of the eight vignettes (Level One) was appraised by using a weighted kappa.26 Disagreements between different categories have different clinical implications. For example, it is more serious to rate equally Play and Non-Play than Pre-Play and Play. Therefore, the relative importance of different types of disagreement among the four categories of the Child Activity (Pre-Play, Play, Non-Play and Interruption) was established in order to perform the data analysis. A disagreement between Play, Non-Play, or Pre-Play and Interruption gets a weight of 1.00; a disagreement between Play and Non-Play gets a weight of 0.75; a disagreement between Pre-Play and Non-Play gets a weight of 0.50; and a disagreement between Play and Pre-Play gets a weight of 0.25. However, weighted kappa is restricted to cases where the number of raters is two and the same two raters rate each subject (vignette).28 In this study, we will present a mean weighted kappa derived from each pair of raters.

For reliability of the categorical scales from Level Two of the CPTI, namely Category of Play Activity, subscales of Child and Adult Script Description, Topic, Theme, and Gender Identity, a multiple-rater kappa is estimated,32,33 in which the average pairwise kappas are adjusted for covariation among pairwise kappas and chance agreements.

For appraising reliability of the remaining quantitative scales of the CPTI (ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 5), an intraclass correlation coefficient is calculated, using a two-way analysis of variance, where the three raters are considered random effects. Thus, differences at the between-raters level are included as error from the analysis. The choice of this statistic is based on the wish of the authors to generalize the estimated results to raters who have at least 1 year of clinical experience and as much as 12 years of experience, so that the CPTI could be reliably used by a variety of clinicians.34,35

Results

Level One: Segmentation:

Agreement among three raters on the segmentation of a child's activity into four categories (Pre-Play, Play Activity, Interruption, and Non-Play) as measured by the weighted kappa coefficient was 0.72.

Level Two: Dimensional Analysis:

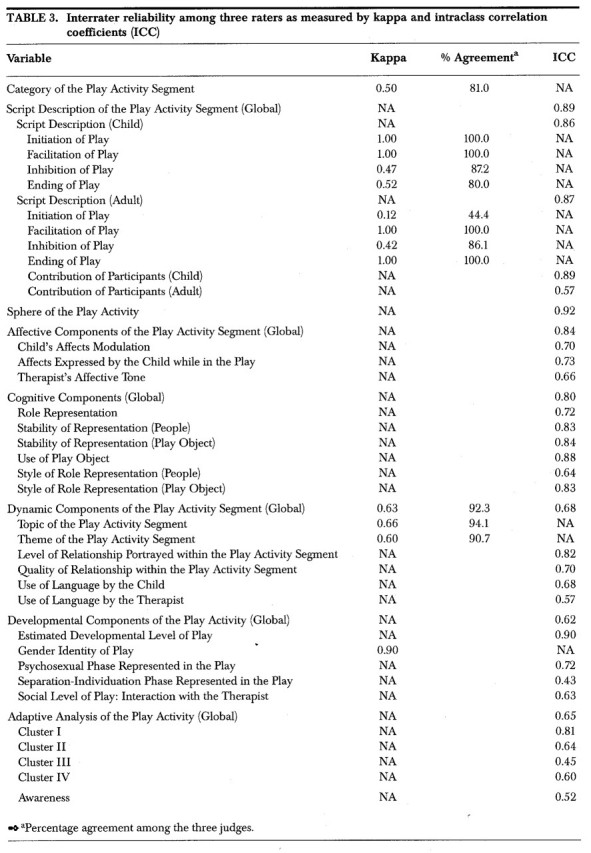

Interrater reliabilities measured by the kappa coefficient for the twelve categorical subscales of the CPTI indicate an average coefficient of 0.65, with range 0.42 to 1.00 (Table 3). The single exception was 0.12, Initiation of Play by Adult.

TABLE 3.

The kappa statistic is extremely sensitive to an unbalanced distribution of categories (presence versus absence), and this sensitivity accounted for some of the variability in our results.

The intraclass correlation coefficients for the 25 main ordinal subscales of the CPTI—specifically the global scores for Script Description, Affective, Cognitive, Developmental, and Dynamic components; Adaptive functions; and Awareness—show a mean tendency of 0.71, with a range from acceptable to excellent (ICC 0.52–0.89). However, there are two subscales at unacceptable levels of reliability, namely Separation-Individuation Phases Represented in the Play (ICC = 0.43), an increment over earlier findings but still below acceptable levels, and Borderline coping/defensive mechanisms (ICC = 0.45), lower than the acceptable levels obtained for other coping/defensive mechanisms.

Generally, the new raters did almost as well as the authors of the scale and in several instances were able to obtain higher levels of interrater reliability. Significant improvements were seen in Style of Role Representation: Play Object (ICC = 0.83, compared with 0.38); Separation-Individuation Phase Represented in the Play (ICC = 0.43, compared with 0.21).

Individual Rater Agreement With the Consensus:

Each rater's performance was compared with the standard provided by the consensus of the authors of the scale. Results indicate that, overall, satisfactory to excellent agreement with the standard was obtained by all three judges. For example, the intraclass correlation coefficients for seven main subscales of the CPTI—specifically the global scores for Script Description, Affective, Cognitive, Developmental, and Dynamic components; Adaptive functions; and Awareness—show a mean of ICC = 0.81 (range 0.61–0.94) for Rater A; a mean of ICC = 0.84 (range 0.69–0.92) for Rater B; and a mean of ICC = 0.84 (range 0.71–0.96) for Rater C.

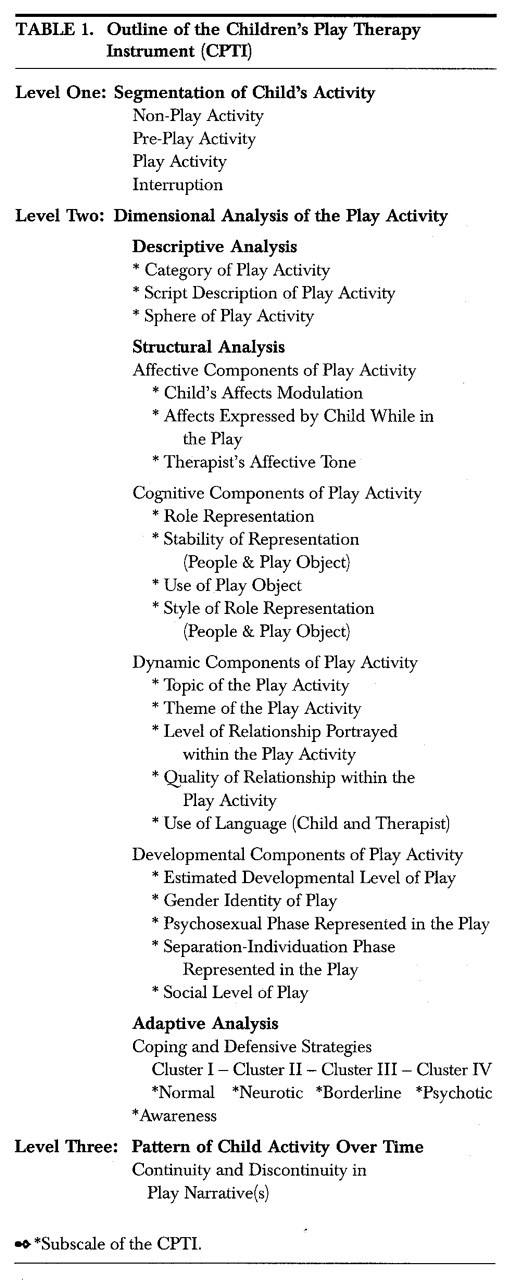

Further comparisons were performed for each individual vignette and revealed a similar pattern of results on the main structural categories of the CPTI. Raters A, B, and C reached good to excellent agreement with the standard. The intraclass correlation coefficients for the four main structural categories of the CPTI, specifically the global scores for Affective, Cognitive, Developmental, and Dynamic components, show a mean of ICC = 0.62 (range 0.58–0.85) for Rater A; a mean of ICC = 0.73 (range 0.59–0.81) for Rater B; and a mean of ICC = 0.69 (range 0.63–0.75) for Rater C.

These comparisons were derived from the consensual mean and standard deviation scores obtained for each vignette (Table 4). One should note that vignettes that are associated with high mean scores and small standard deviation scores are mainly associated with the middle–advanced and late phases of treatment, whereas low mean scores and large standard deviation scores are associated with vignettes from the beginning or middle phases of treatment.

TABLE 4.

Discussion

These preliminary studies demonstrate the feasibility of using the CPTI to measure a child's activity in psychotherapy. The CPTI provides a means to identify play activity within a psychotherapy session. The play activity is then measured from three different perspectives: descriptive, structural, and adaptive. Each of these dimensions consists of individual subscales that are operationally defined. The quantification of these subscales provides both the flexibility to derive individual profiles of play activity in psychotherapy and a methodology to identify relevant dimensions of a child's play activity.

Training procedures established the credibility of these measures in assessing play activity. The independent raters, with varying levels of experience, required 15 hours of training to reach satisfactory levels of agreement. This result is preliminary evidence to suggest CPTI may be a usable tool for researchers and clinicians who receive a minimum of 15 hours of intensive training.

Despite the small number of vignettes used to establish the reliability of the instrument, it must be stated that the vignettes embrace the whole spectrum of the different ordinal scales. The vignettes that showed higher mean scores with smaller standard deviations were associated with the middle–advanced and late phases of treatment; lower mean scores with larger SDs were associated with vignettes from the beginning or middle phases of treatment. Likewise, the raters were consistently able to make these sensitive distinctions. However, in some subscales using the kappa, reliabilities were lowered by a preponderant representation of one of the categories over the other; for example, (Adult) Initiation of Play (k = 0.12) and Functional analysis: Cluster II (k = 0.41). This disproportionate pattern was likely to lower the reliability coefficient each time a disagreement on the less represented category was encountered.

The Separation-Individuation category of the Developmental scale gave results below acceptable standards. A closer examination of raters' individual ratings showed a wide discrepancy among raters. This scale clearly required further definition, particularly as it pertains to higher-functioning children. Further work on clarifying the phases of separation-individuation represented in the child's play resulted in a revision of the definitions of these categories in the manual. Specifically, new examples illustrating these phenomena in children with mild emotional disorders were added in the training. In the prior reliability studies, raters had experienced difficulty making meaningful reference to these categories, except in cases of severe disturbance (psychosis and autism). After a 2-month hiatus, the Separation-Individuation subscale was readministered to the group of three trained raters, and the results obtained were good: ICC = 0.63.

Looking toward the future, a larger database is required, to include both clinical and nonclinical children, to establish definitive reliability and to validate the sensitivity and specificity of the CPTI as a diagnostic tool that discriminates distinctive psychopathological profiles and is sensitive to changes occurring in the course of treatment.

Summary

We described the development of a new and comprehensive measure of a child's play activity in psychotherapy, the CPTI, and presented reliability studies. Using the instrument and accompanying manual, raters were trained to obtain satisfactory to excellent levels of agreement on the segmentation and dimensions of a child's play activity occurring within a psychotherapy session. In addition, each of these trained raters obtained good to excellent agreement with the consensus standard for the scale reached by the authors of the scale. Future planned studies include obtaining reliability on a larger new sample of play sessions and evaluating sequences of play sessions over time. In addition, future validity studies are planned to investigate the concurrence of play profiles with diagnostic categories, attachment behaviors, and outcome variables. These preliminary findings indicate that the CPTI holds promise to become a diagnostic instrument and outcome measure of a child's play activity in psychotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge with appreciation the participation of Elsa Blum, Ph.D., Pauline Jordan, Ph.D., Judith Moskowitz, Ph.D., and Risa Ryger, Ph.D.

References

- 1.Kernberg PF: Las formas del juego: una comunicaci¢n preliminar [The forms of play: a preliminary communication]. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicoan lisis 1996; 1:197–201 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kernberg PF, Chazan SL, Normandin L: The Cornell Play Therapy Instrument. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, York, England, June 1994

- 3.Greenspan SI, Lieberman AF: Representational elaboration and differentiation: a clinical-quantitative approach to the clinical assessment of 2–4 year olds, in Children at Play, edited by Slade A, Wolf DP. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994, 3–32

- 4.Lindner TW: Transdisciplinary Play-based Assessment. Baltimore, Paul H. Brookes, 1990

- 5.Schaefer CE, Gitlin K, Sandgrund A: Play Diagnosis and Assessment. New York, Wiley, 1991

- 6.Bretherton I: Representing the social world in symbolic play, in Symbolic Play, edited by Bretherton I. New York, Academic Press, 1984, 3–41

- 7.Emde RN, Sorce JE: The rewards of infancy: emotional availability and maternal referencing, in Frontiers of Infant Psychiatry, vol 2, edited by Call JD, Galenson E, Tyson R. New York, Basic Books, 1983, 17–30

- 8.Erikson EH: Studies in the interpretation of play. Genetic Psychology Monographs 1940; 22:557–671 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urist J: The Rorschach test and the assessment of object relations. J Pers Assess 1977; 41:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erikson EH: Further explorations in play constructions. Psychol Bull 1941; 38:748–756 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorce JE, Emde RN: Mother's presence is not enough: effect of emotional availability on infant exploration. Dev Psychol 1981; 17:737–745 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stern D: The Interpersonal World of the Infant. New York, Basic Books, 1985

- 13.Piaget J: The Construction of Reality in the Child. New York, Basic Books, 1954

- 14.Tuber S: Assessment of children's object representations with Rorschach. Bull Menninger Clin 1989; 53:432–441 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond D, Kaslow N, Coonerty S, et al: Changes in separation-individuation and intersubjectivity in long term treatment. Psychoanalytic Psychology 1990; 7:363–397 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erikson EH: Childhood and Society, 2nd edition. New York, Norton, 1963

- 17.Coates S, Tuber SB: The representation of object relations in the Rorschachs of extremely feminine boys, in Primitive Mental States and the Rorschach, edited by Lerner H, Lerner P. Madison, CT, International Universities Press, 1988, 647–664

- 18.Zucker KJ, Bradley SJ: Gender Identity Disorder and Psychosexual Problems in Children and Adolescents. New York, Guilford, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Freud A: The concept of developmental lines. Psychoanal Study Child 1963; 18:245–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peller LE: Libidinal phases, ego development and play. Psychoanal Study Child 1954; 9:178–198 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahler M, Pino F, Bergman A: The Psychological Birth of the Human Infant. New York, Basic Books, 1975

- 22.Winnicott D: Playing and Reality. New York, Basic Books, 1971

- 23.Vaillant GE, Bond M, Vaillant CO: An empirically validated hierarchy of defense mechanisms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:786–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry CJ, Kardos ME, Pagano CJ: The study of defenses in psychotherapy using the Defense Mechanism Rating Scale (DMRS), in The Concept of Defense Mechanisms in Contemporary Psychology: Theoretical, Research, and Clinical Perspectives, edited by Hentschel U, Ehlers W. New York, Springer, 1993, 122–132

- 25.Kernberg PF: Current perspectives in defense mechanisms. Bull Menninger Clin 1994 58:55–87 [PubMed]

- 26.Cohen J: Weighed kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968; 70:213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landis JR, Koch CG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33:159–174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartko JJ: On various intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Bull 1976; 83:762–763 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones RR, Reid JB, Patterson GR: Naturalistic observation in clinical observation, in Advances in Psychological Assessment, vol 3, edited by McReynolds P. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass, 1973, 42–95

- 30.Gelfand DM, Hartmann DP: Child Behavior Analysis and Therapy. New York, Pergamon, 1975

- 31.Hartmann DP: Assessing the dependability of observational data, in Using Observers to Study Behavior, edited by Hartmann DP. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass 1982, 51–65

- 32.Conger AJ: Integration and generalization of kappas for multiple raters. Psychol Bull 1980; 88:322–328 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hubert L: Kappa revisited. Psychol Bull 1977; 84:289–297 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86:420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleiss JL, Shrout PE: Approximate interval estimation for a certain intraclass correlation coefficient. Psychometrika 1978; 43:259–262 [Google Scholar]