Abstract

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) has sometimes but not always been considered a psychodynamic psychotherapy. The authors discuss similarities and differences between IPT and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP), comparing eight aspects: 1) time limit, 2) medical model, 3) dual goals of solving interpersonal problems and syndromal remission, 4) interpersonal focus on the patient solving current life problems, 5) specific techniques, 6) termination, 7) therapeutic stance, and 8) empirical support. The authors then apply both approaches to a case example of depression. They conclude that despite overlaps and similarities, IPT is distinct from STPP.(The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 1998; 7:185–195)

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT),1 a manual-based treatment for particular psychiatric populations, has been alternately included in and rejected by the psychodynamic community. Some see it as founded on psychodynamic principles, while others dismiss it as a lightweight alternative to the psychodynamic tradition, a Band-aid therapy that misses the larger point of treating character. Until recently IPT was almost entirely a research intervention, described in clinical research trials but otherwise unfamiliar to practicing clinicians. Many may not really know what IPT is. (Perhaps that explains why so many inadvertently mislabel it “ITP.”) In contrast, psychodynamic therapy has been widely used but less researched.

This article differentiates two terms that are too often loosely used: (brief) “psychodynamic” and “interpersonal” psychotherapy. The issue of whether IPT is a form of short-term dynamic psychotherapy (STPP) has been frequently broached in clinical workshops but never fully confronted in the literature, and ambiguity about the issue is evident even in the IPT manual. This issue deserves examination for several reasons:

The growing prominence of IPT as a research and clinical treatment2 suggests the need to define it relative to other psychotherapies.

If IPT differs significantly from STPP, it may require a distinct course of training. Such IPT training has been defined, although few trainees and clinicians have received it.3 If the two do not greatly differ, any well-trained STPP psychotherapist may be able to deliver IPT without intensive training.

IPT was designed as a utilitarian psychotherapy that codified existing practices. Klerman et al.1 wrote that “Many experienced, dynamically trained . . . psychotherapists report that the concepts and techniques of IPT are already part of their standard approach” (p. 17). A retrospective analysis of the theoretical stance of IPT may place it more firmly in relationship to the historical and conceptual contexts of earlier psychotherapies.

IPT has been included in some meta-analyses of psychodynamic outcome studies. IPT could provide needed empirical data for psychodynamic treatments if the two modalities belong to the same family. If they do not, trials comparing them might establish differential efficacies.

A debate arose in the research literature when Crits-Christoph4 and Svartberg and Stiles5 published meta-analyses of the efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy that yielded different results. Svartberg and Stiles6 noted that one reason for their differing findings was that Crits-Christoph had included IPT among psychodynamic studies, bolstering his results.

Svartberg and Stiles maintained:

Although many dynamic psychotherapists report that the concepts and techniques of interpersonal psychotherapy are part of their therapeutic skills, there are vital differences between interpersonal psychotherapy and brief dynamic psychotherapy.6

They then cited the IPT manual:

For purposes of theoretical clarification and of research design and methodology, we often find it useful to emphasize the difference between interpersonal and psychodynamic approaches to human behavior and mental illness.1 (p. 18).

Svartberg and Stiles present this distinction as definitive, but to our ears the wording they cite sounds more cautious. Crits-Christoph, who earlier conceded that IPT “may be quite distant from the psychoanalytically oriented forms of dynamic therapy more commonly practiced”4 (p. 156), gave similarly incomplete justification for deeming IPT psychodynamic, namely that most IPT therapists in early trials were psychodynamically trained and adapted easily to IPT.7 This hardly makes the therapies identical.

The IPT manual waffles on the issue. It contrasts IPT with “psychoanalytically oriented psychodynamic therapies,” citing differences in conceptualizing the patient's problem: IPT does not use transference interpretations or focus on childhood antecedents; IPT does not attempt personality change; and IPT therapists can accept small gifts from patients without examination (pp. 166–167). Yet it also uses the words “another difference between IPT and other psychodynamic psychotherapies” (p. 167; our italics).

Should IPT be considered a brief psychodynamic psychotherapy? We shall briefly define the two approaches, then consider their overlap.

The Two Approaches Compared

Brief Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Psychodynamic psychotherapy is a sprawling field, and even within STPP there are numerous short-term variants. These include drive/structural models,8–10 existential models,11 relational models,12–14 and integrative models.15,16 STPP is usually designed to promote insight rather than to treat specific disorders. No form of STPP has been developed specifically to treat depression, as IPT was.

Although heterogeneous, STPP variants share the following aspects: 1) their theory about the origin of psychopathology is psychoanalytically grounded; 2) key techniques are psychoanalytic, such as confrontation, interpretation, and work in the transference; 3) patients are selected for treatment; 4) during initial sessions a dynamic case formulation is developed, and a focus based on this formulation is established and maintained throughout treatment.17

Although relationally focused STPPs may be gaining ground, we believe that conflict-oriented approaches still hold sway: they appear to be most widely used and are probably what most clinicians think of as STPP. We therefore define STPP as a treatment of less than 40 sessions that focuses on the patient's reenactment in current life and the transference of largely unconscious conflicts deriving from early childhood.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

Compared with STPP, IPT is an essentially unified treatment with far less history and opportunity for diffusion. Developed by Klerman, Weissman, and colleagues to treat outpatients with nondelusional major depression in a time-limited format, IPT has since been adapted for other psychiatric disorders.18 In the initial phase (1–3 sessions), the IPT therapist diagnoses a psychiatric disorder and an interpersonal focus; links the two for the patient in a formulation; and obtains the patient's explicit agreement to this formulation, which becomes the treatment focus. In the middle phase, the therapist employs practical, optimistic, forward-looking strategies to provide relief.

Possible interpersonal foci, derived from psychosocial research on depression, are 1) grief (complicated bereavement), 2) role dispute, 3) role transition, and 4) interpersonal deficits.1 A brief termination phase concludes acute treatment. Based on the premise that life events affect mood, and vice versa, IPT offers strategies that maximize the opportunity for patients to solve what they often see as hopeless interpersonal problems. If patients succeed in changing their life situations, their depression usually remits as well. A series of randomized controlled treatment trials has demonstrated that IPT both treats episodes of illness and builds social skills.2,19

Similarities and Differences

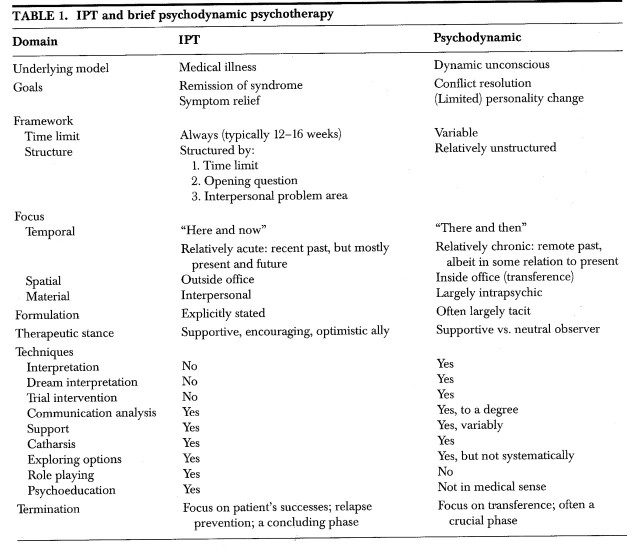

IPT is defined by its 1) time limit, 2) medical model, 3) dual goals of solving interpersonal problems and syndromal remission, 4) interpersonal focus on the patient solving current life problems, 5) specific techniques, 6) termination, 7) therapeutic stance, and 8) empirical support. We shall compare each of these elements in turn with the features of STPP, focusing on depression—the modal IPT diagnosis—as the treatment target. Table 1 contrasts IPT and STPP.

TABLE 1.

1. Time Limit:

IPT has a strict time limit, established at its outset, ranging for acute treatment from 12 to 16 weekly sessions. Although this duration arose as a compromise between the needs of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in randomized trials, it has proved an adequate length and an important tool. Brevity of treatment pressures the depressed patient and the therapist to work quickly.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy, like psychoanalysis, was traditionally an open-ended treatment. Malan,8 Sifneos,9 Davanloo,10 Mann,11 Luborsky,12 Horowitz et al.,20,21 Strupp and Binder,22 and others developed short-term psychodynamic interventions with more defined foci and limits. Their brevity is stated, but their exact duration is often not specified, at the outset. Some have variable10,12,22 or time-attendant9 lengths, based on evidence of therapeutic progress.23 In contrast to the 12 to 16 sessions of IPT, most STPPs comprise 20 to 25 sessions.

2. Medical Model:

The IPT focus is illness based. The patient's problem is defined as a medical illness: a mood disorder may be usefully compared to hypertension, diabetes, and other medical disorders that respond to behavioral and pharmacological interventions. Giving the patient a medical diagnosis and the “sick role”1,24 is a formal aspect of the first phase of IPT. These maneuvers aim to help depressed patients recognize depressive symptoms as ego-dystonic and to relieve self-criticism by helping them to blame an illness (and an interpersonal situation), rather than themselves, for their difficulties. The sick role also entails responsibility to work to recover the lost, healthy role. IPT therapists, while often using psychodynamic knowledge to “read” psychological patterns of patients, carefully avoid prejudging whether patients who present with Axis I disorders such as major depression or dysthymic disorder have personality disorders.25

The IPT approach relieves guilt and diminishes the risk that depressed patients may unfairly blame their character rather than illness or circumstances. It avoids the potential confusion of depressive state with, say, masochistic traits.25 In contrast, STPP often focuses on intrapsychic conflicts, unconscious feelings, and character defenses rather than formal diagnoses and the concept of illness. Many STPP practitioners may deem depressive symptoms less important than do IPT therapists, seeing such symptoms not as outcome variables but as epiphenomena of underlying characterological issues. Whereas for IPT therapists the Axis I diagnosis is paramount, STPP psychotherapists often focus on characterological defenses, informally diagnosed “Axis II.”

Following the medical model, IPT uses DSM-IV diagnosis as its inclusion criterion. Inclusion criteria for STPP tend to be factors such as feasibility of establishing a therapeutic focus, ability to form an emotional attachment, and motivation for change.23

3. Goals:

IPT has dual aims: to solve a meaningful interpersonal problem, and (thereby) to relieve an episode of mood disorder. The IPT therapist defines these two targets during the initial phase, links them in an interpersonal formulation,26 and obtains the patient's agreement on this formulation as a focus before proceeding into the main treatment phase. The formulation, a non-etiologic linkage of mood and environmental situation, explicitly states the therapist's understanding of the case:

As we determined by DSM-IV, you are going through an episode of major depression, a common illness that is not your fault. To me it seems that your depressive episode has something to do with your father's death and your difficulty in mourning him. Your symptoms started shortly after that. I suggest that over the next 12 weeks we try to solve your problem with mourning, which we call complicated bereavement. If we solve that, your depression will very likely improve.

STPP seeks to increase the patient's understanding of his or her internal functioning. External change implicitly follows, but it is not the prime focus of treatment.

In summary: the goal for IPT is to treat a specific psychiatric syndrome by helping the patient to change a current life situation; the goal for STPP is to increase understanding of intrapsychic conflict. These approaches reflect differing concepts of psychopathology. Implicit in these definitions of therapeutic goals are their indications. IPT is indicated only for syndromes for which its efficacy has been empirically demonstrated (major depression, bulimia). STPP has been less concerned with specific diagnoses, although Horowitz and co-workers do focus on stress and bereavement syndromes.20,21 Some forms of STPP deem significant symptomatology a contraindication.9

4. Interpersonal Focus:

IPT focuses on events in the patient's current life (“here and now”) outside the office and on the patient's reaction to these life events and situations. Patient problems are categorized within the four interpersonal problem areas, usually elaborated by a personalized metaphor.25 STPP, even when emphasizing events,20 focuses on transference in the office and the linking of extrasession interpersonal events to the transference. The phrase “here and now” in a psychodynamic context refers to what happens in STPP sessions. IPT instead concentrates on recognition of recent traumatic life events, grieving their costs but simultaneously emphasizing the positive potentials of the present and future. IPT is “coaching for life” more than introspection.

5. Specific Techniques:

IPT is more innovative in its use of focused strategies than unique in its particular techniques. For each interpersonal problem area there is a coherent set of strategies. Nonetheless, several key techniques are frequently used. Some, but not all, derive from psychodynamic practice (see Table 1).

Sessions begin with the question, “How have things been since we last met?” This focuses the patient on the interval between sessions and elicits either a mood or an event. The therapist then helps the patient to link the two. Depressed patients soon learn to connect environmental situation and mood and to recognize that they can control both through their actions. Starting with a recent, affectively charged event allows sessions to move to the interpersonal problem area, maintaining the focus without rendering the discussion intellectualized or affectless.

Having discovered a recent life situation, the therapist asks the patient to elaborate events and associated feelings to determine where things might have gone right or wrong (communication analysis). The therapeutic dyad explores what happened, how the patient felt, what the patient wanted in the situation, and what options the patient had to achieve it. If the patient handled the situation less than optimally, role playing may prepare the patient to try again.

IPT does not use STPP interventions such as genetic or dream interpretations. Both approaches pull for affect and catharsis. But for IPT, catharsis alone is insufficient: the patient must also transmute feeling into life changes. Catharsis in STPP may lead the patient to an increased sense of safety in sessions, facilitating subsequent deeper exploration of conflicted feelings. The goal is increased self-knowledge on which the patient may act independently. Life change might be considered a good outcome of STPP, but it would come as a by-product of insight. By contrast, IPT emphasizes action rather than exploration and insight, in part because mobilization and social activity benefit depressed patients. The IPT therapist actively supports the patient's pursuit of his or her wishes and interpersonal options.

STPP therapists help patients focus on transferential and interpersonal themes (e.g., Luborsky's Core Conflictual Relationship Theme12); however, sessions are less structured by the therapist and more dependent on the patient's generating material—which it might be difficult for depressed patients to do productively.

6. Termination:

In IPT, termination means graduation from therapy, the bittersweet breakup of a successful team. It is a coda to treatment, important but secondary to the middle phase. The final sessions address the patient's accomplishments, the patient's competence independent of the therapist, and relapse prevention.

Termination in STPP is a more important phase than in IPT and concentrates far more on the patient's responses to therapy ending: indeed, the therapy often turns on this.8 A key STPP technique is working through the separation issues of termination, especially as manifested in the transference.

7. Therapeutic Stance:

STPP tends toward therapist neutrality and relative abstinence in order to allow the transference to develop, whereas the IPT therapist assumes the openly supportive role of ally. A practical, optimistic, and helpful approach is deemed necessary to counter the negative outlook of depressed patients. Although encouraging patients to develop their own ideas, IPT therapists offer suggestions when needed. When the patient does something right, the therapist offers congratulations—a “cheerleading” style that might disconcert some STPP therapists.

IPT and STPP share some attributes: time constraint, narrow focus, and modality-trained therapists. Both use support, a warm alliance, and careful exploration of interpersonal experiences. They share a positive, empowering, collaborative stance. Most STPP therapists use traditional analytic techniques (transference or genetic interpretation, clarification, confrontation, defense analysis) to help patients explore and understand themes or conflicts. IPT also might use clarification to aid a depressed patient's understanding of an interpersonal dispute. Some STPPs specify that therapists should be relatively supportive11 or active.8

An illustrative difference between the two approaches might arise with an irritable, depressed patient at risk to develop a negative transference to his therapist. The STPP therapist would allow the transference to develop, then interpret it to the patient to explore its meaning. The IPT therapist would focus the patient on interpersonal relationships and events in the patient's outside life that might provoke anger or irritability, and would also blame the depressive disorder itself when appropriate. This active, outward-looking approach minimizes the opportunity for a negative transference to build: rather, the therapist becomes the patient's ally in fighting depression and outside problems. (This reverses the psychoanalytic principle that transference brings into the therapeutic relationship patterns that the patient enacts everywhere. In IPT, if the patient has feelings about the therapist, there is probably a culprit elsewhere.) Resolving outside problems and depressive symptoms cements the therapeutic alliance, so that negative transference—which may reflect the patient's clouded depressive outlook—fades. If the patient's feelings unavoidably perturb the therapeutic alliance, the IPT therapist explores them as interpersonal, real-life, here-and-now issues rather than as transference.

If a patient repeatedly arrives late for sessions, the STPP therapist might explore aspects of the patient's character and feelings about the therapist that might contribute to the lateness. From the IPT perspective, this risks potentially reinforcing the patient's already excessive self-blame. The IPT therapist would excuse the patient, sympathizing that it's hard to get out of bed and arrive punctually when you feel depressed and lack energy, and acknowledging that the patient's level of anxiety might make it hard to contemplate sitting through a full session. The IPT therapist would thus blame the depression, not the patient—who feels bad enough already. The therapist would mention the time limit (“Unfortunately we only have eight sessions left, and we really need to use all the remaining time to find ways to fight your depression”) in order to discourage future tardiness. Lateness in other relationships might be explored with the goal of building interpersonal skills (self-assertion, expression of anger) in these external settings.

STPP treats the patient's “resistance” to employing healthy solutions as meaningful; IPT treats the “resistance” as illness—namely, depression. The IPT “corrective emotional experience” lies partly outside the office, in the amelioration of interpersonal situations external to therapy. The STPP corrective emotional experience lies primarily inside the office, in the patient's newfound ability to express warded-off feelings to an optimally responsive person.

8. Empirical Support:

The demonstrated efficacy of IPT in treating mood and other psychiatric syndromes in randomized clinical trials2 sets it apart from most STPP treatments, for which empirical evidence of efficacy in treating particular syndromes is meager.5,23 Luborsky and co-workers produced impressive results in treating opiate-maintained patients with STPP,27 an area where IPT failed.28 This indirect comparison suggests differences between the approaches. There have been no direct comparisons of IPT and STPP in treating major depression. Some reports suggest, however, that psychodynamic psychotherapy may not be the ideal treatment for mood disorders.3,29 Efficacy data provide an important foundation permitting the IPT therapist to meet the depressed patient's pessimism with equal and opposite optimism. Consonant with an empirical approach, many IPT therapists serially administer depression rating instruments during treatment.

A case example may highlight differences between IPT and STPP.

Case Example

Ms. A., a 34-year-old married businesswoman, presented with the chief complaint, “I'm feeling depressed.” She reported that 5 months earlier she had received a long-sought promotion, which increased her responsibility at work. Her longer working hours and heightened career opportunities increased ongoing tension with her husband over whether to have a second child. She became increasingly doubtful about another pregnancy; her husband became more insistent upon it. She reported that over the past 3 to 4 months she had experienced depressed mood, early and mid- insomnia, decreased appetite and libido, an 8-pound weight loss, low self-esteem, and greater guilt. She felt anxious and irritable with her 35-year-old computer programmer husband, her 8-year-old son, and co-workers.

Psychodynamic Approach:

An STPP therapist would begin by developing a dynamic formulation of the case. This formulation would comprise a specific constellation of dynamic elements: defenses, anxiety, and unconscious impulse/feeling, as well as their interrelationships. Central to the case is Ms. A.'s inability to express anger adaptively toward her husband. The reason for this might be anxiety-based fantasies about hurting and possibly losing her husband if the angry impulses were released. These impulses are defended against through 1) deflecting the impulse and directing it inward (causing depression); 2) acting out (being irritable, which is not adaptive anger); 3) displacement onto her son and co-workers; and possibly 4) taking the victim role (a self-pitying, “poor me” attitude, which is also maladaptive).

Treatment would begin with the therapist pointing out impulses, anxious fantasies, and defenses in relation to a current person (husband), a past person (father, mother), and the therapist. If the patient came late to sessions, the therapist might interpret this transferential manifestation of unexpressed anger, linking it to anxiety about expressing anger directly to her husband, or to her domineering parents in the past. Recognition of this conflict would be considered inherently therapeutic. The aim is to help the patient recognize how she defends herself against frightening angry impulses. The next step, at a deeper level, is to explore the angry impulses: to have her experience the full feeling of anger and to facilitate its expression in the transference. In the presence of a nonjudgmental therapist, this represents a corrective emotional experience for the patient and, as such, is considered key to alleviating symptoms and to limited personality change.

IPT Approach:

The patient meets criteria for a DSM-IV major depressive episode,30 an indication for IPT. If exploration revealed no other precipitant (such as complicated bereavement), the therapist would link the onset of the mood disorder to one of two probable interpersonal problem areas: either a role transition (the job promotion and its consequences) or a role dispute (with the husband over having another child). Depending on which of these intertwined themes emerged as most salient to the patient, the therapy might focus on either or both. From the presentation, it appears that her conflicts are at home (role dispute) rather than with the job per se.

The therapist would present this linkage to the patient (“Your depression seemed to start after you got your promotion and you and your husband began to argue about having another child”) and would give the patient the sick role. If the patient accepted the formulation as a focus for time-limited treatment, the therapist would then discuss with the patient what she wanted: How could she balance work and home? How much pleasure does work give her? Are there ways to resolve the marital dispute? Once her wishes are determined, what options does the patient have to resolve these problems? In a role dispute with the husband, the goal would be to explore the disagreement, to see whether the couple is truly at an impasse, and to explore ways to resolve it. Addressing the role dispute might well require exploring how the patient expresses anger, which could be fine tuned through role-play in the office. With therapist support, Ms. A. would attempt to renegotiate her current life situation to arrive at a satisfactory new equilibrium. Achieving it, or at least trying to the best of her ability (her husband might be unreasonable, but she could at least handle her side of the matter appropriately), would very likely lead to remission of her mood disorder.

Discussion

IPT bears similarities to some forms of STPP, but it differs sufficiently that it should be considered distinct. IPT was developed to treat depression, STPP for a range of psychopathologies. The IPT rationale does not pretend to explain etiology. Rather, IPT is a pragmatic, research-proven approach that addresses one important aspect of depressive syndromes and frequently suffices to treat them. To the extent that IPT invokes theory, it relies on psychosocial research findings (for example, the association of marital conflicts and depressed wives1) and commonsense but clinically important ideas, such as “life events affect mood.”

IPT and STPP may (should?) ultimately address overlapping problem areas, with the distinction that STPP seeks intrapsychic as well as interpersonal patterns. STPP uses history and transference to determine the focal problem. IPT sticks to history: although the patient's interpersonal behaviors in sessions may convey important information, the transference is not addressed. To a greater extent than STPP, IPT emphasizes finding concrete solutions and changing relationships, using techniques such as role playing to prepare the patient for such steps. Reflecting these distinctions, the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program31 developed adherence measures that distinguish IPT from “tangential” psychodynamic techniques.32

We conclude:

1. IPT has distinct emphases.

A psychodynamic background, which most IPT therapists (beginning with Klerman and Weissman) have had, is helpful to “read” patients, to subtly manipulate (rather than interpret) the transference. But the IPT conceptualization of depression as an illness, and its focus on depressive illness rather than on characterological “roots,” represents a significant difference from STPP. The emphasis on outcome and on success experiences in the patient's life has also been less characteristic of STPP. In teaching IPT to psychodynamic therapists—even Sullivanian (“interpersonal”) psychoanalysts—we sometimes see them struggling to adjust to the IPT approach.

2. IPT is not simply “supportive” dynamic therapy.

IPT does share some features with supportive therapies. But “supportive” has been a pejorative psychoanalytic term for any not-formally-expressive, not-insight-oriented psychotherapy.33 As such, “supportive” encompasses not only formal psychodynamic approaches to supportive therapy,34 but almost anything else: the term roughly translates to “not psychoanalytic.” IPT is more active, has more ambitious goals (syndromal remission; helping patients to rapidly change interpersonal environments), and very likely accomplishes more than typical (if there is such a thing) supportive therapy. This was our finding in comparing IPT and a supportive, quasi-Rogerian psychotherapy in treating depressed HIV-positive patients.35 If IPT is not psychodynamic, it is not exactly “supportive,” either, although IPT therapists do provide support.

3. IPT is distinct in its interpersonal focus.

STPP can have a strong interpersonal focus, but it need not. Even when it does, techniques and focus differ from those of IPT: for example, outside interpersonal relationships are frequently linked to transference. STPP as a whole may be moving toward a more interpersonal focus. (Lacking a consensus, it is hard to know.) If so, it is probably more skewed in that direction than much other psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Some STPP variants clearly have more interpersonal emphasis than others, and thus arguably overlap more with IPT. One example is the time-limited psychodynamic psychotherapy (TLDP) of Strupp and Binder.22 Development of this approach was influenced by psychoanalysts such as Alexander and French, Gill, and Klein as well as STPP theorists such as Malan, Sifneos, Davanloo, and Mann.36 During initial sessions, TLDP therapists formulate a salient maladaptive interpersonal pattern as it relates to (in order of priority) the therapist, current others, and past others. Throughout treatment, TLDP therapists identify the influence of this pattern on the patient–therapist relationship: how the patient's expectations about self and others are enacted in the transference. As described by Elkin at al.,31 “TLDP therapists' technical approach emphasizes the analysis of transference and countertransference in the here and now” (p. 144).

Although TLDP has an interpersonal therapeutic focus, it differs drastically from the IPT therapist's practical, outside-the-office emphasis and interventions. Indeed, TLDP may more closely resemble psychoanalysis proper than IPT in its heavy emphasis on transference and countertransference.37

4. IPT and STPP differ markedly in their treatment range.

IPT is intended as a limited intervention addressing particular Axis I syndromes. STPP derives from an all-encompassing psychodynamic approach to psychopathology, yet paradoxically has often specified extremely limiting selection criteria for its application (see Sifneos,9 for example). Absent comparative research data, we know little about the differential therapeutics38 of STPP and its indications relative to IPT for particular diagnostic groups.

An important exception to this rule is the STPP of Horowitz and colleagues.20,21 This focuses on one of IPT's four foci, grief reactions, but addresses them differently. Horowitz's approach is characterized by 1) general principles defined by Malan, Sifneos, and Mann, including clarification; confrontation; interpretation of impulses, anxiety, and defenses; separation and loss issues regarding the therapist and current and past others; and 2) specific principles about the handling of affects and views of self and other activated by the traumatic event, such as reality testing of fantasies, abreaction, and catharsis. The active use of the transference, the reliance on traditional psychodynamic techniques, and the aim of modifying long-standing personality patterns are but a few features differentiating this approach from IPT.

5.20 Training for IPT requires a distinct approach.

We teach IPT separately, as a form of time- limited therapy distinct from STPP. This suggests important heuristic differences. Indeed, for reasons already articulated (see Table 1), conceptual and technical differences would make it difficult to teach IPT as a subtype of STPP.

6.20 Despite overlap, IPT and STPP are distinct.

A participant in an IPT workshop said: “IPT isn't psychodynamic, but it isn't anti-dynamic, either.” This puts it as well as anyone has. The obvious overlap in these therapies includes the “nonspecific” factors of psychotherapies 39 as well as the backgrounds of most of the IPT therapists trained to date. Yet differences in goals, techniques, outlook, and research data are meaningful. IPT should not be grouped with STPP. Although it may have roots in psychodynamic soil, it differs sufficiently in its outlook and practice to deserve to be considered apart.

Acknowledgments

Alan Barasch, M.D., a colleague at the Payne Whitney Clinic, provided important concepts and arguments in an early form of this paper. David Dunstone, M.D., of Michigan State University, Kalamazoo, MI, provided the final quote. This work was supported by Grants MH46250 and MH49635 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by a fund established in the New York Community Trust by DeWitt-Wallace.

References

- 1.Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, et al: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984

- 2.Weissman MM, Markowitz JC: Interpersonal psychotherapy: current status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz JC: Teaching interpersonal psychotherapy to psychiatric residents. Academic Psychiatry 1995; 19:167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crits-Christoph P: The efficacy of brief dynamic psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svartberg M, Stiles TC: Comparative effects of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:704–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svartberg M, Stiles TC: Efficacy of brief dynamic psychotherapy (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crits-Christoph P: Dr. Crits-Christoph replies (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:684–6858465905 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malan DH: The Frontier of Brief Psychotherapy. New York, Plenum, 1976

- 9.Sifneos PE: Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Plenum, 1979

- 10.Davanloo H (ed): Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, vol I. New York, Jason Aronson, 1980

- 11.Mann J: Time-Limited Psychotherapy. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1973

- 12.Luborsky L: Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Manual for Supportive/Expressive Treatment. New York, Basic Books, 1984

- 13.Strupp HH, Hadley SW: Specific vs. non-specific factors in psychotherapy: a controlled study of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:1125–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss J, Sampson H: The Psychoanalytic Process: Theory, Clinical Observations, and Empirical Research. New York, Guilford, 1986

- 15.Gustafson JP: An integration of brief dynamic psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaillant LM: Changing Character: Short-term Anxiety-Regulating Psychotherapy for Restructuring Defenses, Affects, and Attachment. New York, Basic Books, 1997

- 17.Crits-Christoph P, Barber JP (eds): Handbook of Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Basic Books, 1991

- 18.Klerman GL, Weissman MM (eds): New Applications of Interpersonal Therapy. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993

- 19.Weissman MM, Klerman GL, Prusoff BA, et al: Depressed outpatients: results one year after treatment with drugs and/or interpersonal psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:52–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horowitz MJ: Short-term dynamic therapy of stress response syndromes, in Handbook of Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy, edited by Crits-Christoph P, Barber J. New York, Basic Books, 1991, 166–198

- 21.Horowitz MJ, Marmar C, Weiss D, et al: Brief psychotherapy of bereavement reactions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:438–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strupp H, Binder J: Psychotherapy in a New Key: A Guide to Time-Limited Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Basic Books, 1984

- 23.Svartberg M: Characteristics, outcome, and process of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: an updated overview. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 1993; 47:161–167 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsons T: Illness and the role of the physician: a sociological perspective. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1951; 21:452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markowitz JC: Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Dysthymic Disorder. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998

- 26.Markowitz JC, Swartz HA: Case formulation in interpersonal psychotherapy of depression, in Handbook of Psychotherapy Case Formulation, edited by Eells TD. New York, Guilford, 1997, 192–222

- 27.Woody GE, Luborsky L, McLellan AT, et al: Psychotherapy for opiate addicts: does it help? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:639–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rounsaville BJ, Glazer W, Wilber CH, et al: Short-term interpersonal psychotherapy in methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:629–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaughn SC, Roose SP, Marshal RD: Mood disorders among patients in dynamic therapy. Presented in Symposium 121: Character and Chronic Depression: Listening to Data, at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, NY, May 1996

- 30.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994

- 31.Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:971–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollon SD: Final report: system for rating psychotherapy audiotapes. Bethesda, MD, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1984

- 33.Hellerstein DJ, Pinsker H, Rosenthal RN, et al: Supportive therapy as the treatment model of choice. J Psychother Pract Res 1994; 3:300–306 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rockland LH: Supportive Therapy. New York, Basic Books, 1989

- 35.Markowitz JC, Klerman GL, Clougherty KF, et al: Individual psychotherapies for depressed HIV-positive patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1504–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Binder J, Strupp H: The Vanderbilt approach to time-limited dynamic psychotherapy, in Handbook of Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy, edited by Crits-Christoph P, Barber J. New York, Basic Books, 1991, 137–165

- 37.Swartz HA, Markowitz JC: Time-limited psychotherapy, in Psychiatry, vol 2, edited by Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1997, 1405–1417

- 38.Frances A, Clarkin JF, Perry S: Differential Therapeutics in Psychiatry: The Art and Science of Treatment Selection. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1984

- 39.Frank J: Therapeutic factors in psychotherapy. Am J Psychother 1971; 25:350–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]