Abstract

The authors have reported that adolescents with major depressive disorder had a higher remission rate with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) than with systemic behavioral family therapy (SBFT) or nondirective supportive therapy (NST). Parent-rated treatment credibility deteriorated from baseline to end of treatment if patients were treated with SBFT or NST, compared with CBT. The present study evaluated the following variables as predictors of change in parent- rated credibility over time across the three treatment cells: severity of child's and parents' depression at baseline; parent-rated family climate at baseline; clinician age, gender, and years of clinical experience; and change in severity of child's depression and in family climate. The greater the baseline depression of children treated with CBT and NST, but not SBFT, the more favorable the change in parent-rated credibility at the end of treatment. Findings suggest that any improvement (for CBT) or a supportive therapeutic contact (for NST) may appeal to parents of severely depressed children.

Keywords: Depression; Adolescents; Psychotherapy, Cognitive and Behavioral; Perceptions of Treatment Credibility

In recent years, emerging consumer advocacy with regard to mental health care has accompanied growing recognition of the importance of patients' perceptions of the treatment interventions they are receiving.1,2 The concept of treatment credibility is of particular relevance in this respect.3 Treatment credibility can be defined as the extent to which patients feel that the treatment to which they have been assigned is appropriate, logical, and helpful and is one that could be recommended to a friend.3 The scale derived from this concept, the treatment credibility analogue, has been used successfully in evaluating the acceptability and credibility of various treatment strategies, including systematic desensitization, implosion, progressive relaxation, and cognitive therapy.3–6

Treatment credibility is regarded as a well-defined, relatively comprehensive, and operational construct,3,7 and it is significantly associated with a related construct, patients' satisfaction with treatment.6 Whereas some studies have found the treatment analogue scale score to be stable over the entire course of treatment,6 others have found it to change during treatment.5,8 particularly as a function of the patient's progress.7 The treatment credibility analogue has also been found to be positively correlated with various parameters related to the treatment process, such as degree of patients' engagement, perceived expertise of the therapist, relationship with the therapist, and number of sessions attended.4,6,9

Recently there has been a growing interest in the perspectives of parents of psychiatric patients on the treatment of their children.2 Satisfaction and collaboration with treatment providers by parents of emotionally disturbed adults10,11 and children12–14 have been associated primarily with three parameters: the degree of family involvement with the patient's treatment; the application of the treatment not only to the patient but also to the family; and the attitude of the therapist to the family.

We previously showed that adolescents diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) respond better to individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), compared with systemic behavioral family therapy (SBFT) and nondirective supportive therapy (NST).15 In that study, we also evaluated the treatment credibility of patients and parents at baseline and at the end of treatment. Although the adolescents' perceptions did not change following treatment, we found a significant overall group-by-time interaction in the way the parent- rated credibility of their child's treatment changed over time. Specifically, the degree of credibility the parents assigned to treatment deteriorated over time among those parents whose children were treated with either SBFT or NST, compared with CBT, for which credibility tended to remain stable.15

The differential outcomes and credibilities in the CBT, SBFT, and NST groups afford us the opportunity to identify factors that may predict the differences in parent-rated credibility change among the three treatment cells. Drawing on studies of treatment credibility and of patients' and parents' satisfaction with treatment, we hypothesized the following variables to have the potential to predict this difference: 1) perceived treatment outcome1,16 in terms of decreased symptomatology and distress;17 2) clinical characteristics of patients—particularly the severity of the mental disorder17 parameters related to the families,18 including parental psychopathology17 and perceptions of family cohesion;19 and 3) therapist-related variables,20 namely, age, gender, and years of clinical experience of the therapist.4,9 This evaluation was the focus of the present study.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were 13- to 18-year-olds of normal intelligence who were living with at least one parent or guardian, met DSM-III-R21 criteria for MDD, and had an intake Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)22 score of 13 or more.15 Exclusion criteria included any psychosis, bipolar I or II disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorder, substance abuse, ongoing physical or sexual abuse, pregnancy, and chronic medical illness.

Subjects were recruited from the Child and Adolescent Mood and Anxiety Disorder Clinic at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, PA, from October 1991 through May 1995. Of 122 eligible subjects, 107 agreed to participate in the study. Incentive for treatment included free treatment and participant payment for the completion of evaluations. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and subjects and their parents signed an informed consent document. The caretaking parents or guardians of 104 out of 107 subjects (97.2%) were evaluated.

Treatment Procedure

As per our previous reports, subjects were randomly assigned to either CBT, family therapy, or supportive treatment.15 Treatment consisted of 12 to 16 sessions delivered in 12 to 16 weeks in each of the three cells. All therapists had master's degrees and a median of 10 years of clinical experience. There were no differences across treatment with respect to clinician's age, gender, or years of experience.15 Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was derived from Beck's CBT.23 It emphasized collaborative empiricism, the importance of socializing the patient to the CBT model, and the monitoring and modification of automatic thoughts, basic assumptions, and core beliefs.15 Systemic Behavioral Family Therapy (SBFT) combined Functional Family Therapy24 and the problem-solving model of Robin and Foster.25 It focused on adequate communication and problem-solving skills, and the identification and alteration of dysfunctional interaction patterns among family members. Nondirective Supportive Therapy (NST), designed to control for the nonspecific aspects of treatment, consisted of the provision of support, affect clarification, and active listening.15 Up to 4 hours of auxiliary sessions were allocated to meet with the family (CBT or NST) or with the child individually (SBFT). Depressed parents who were not already in treatment were offered pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy at no cost, although only a small proportion availed themselves this treatment. Expert ratings of videotaped sessions demonstrated that the treatments in all three cells were delivered with fidelity and were distinct from each other.15

A total of 7 subjects were removed from treatment because of continued MDD, a BDI score of 13 or greater, a suicide attempt, or failing to make symptomatic improvement. Of these 7 subjects, 1 received CBT, 3 received SBFT, and 3 received NST. Attrition was evenly distributed among the groups (P=0.51).15

There were no significant differences among the three treatment groups at intake on the demographic and clinical variables, with the exception that the subjects treated with NST tended to be more functionally impaired.15 However, we decided not to control for functional impairment in the present analyses because in the overall analysis, the three treatment groups differed at only a trend level (P=0.06). There were also no significant differences across cells with respect to treatment fidelity or protocol deviations—dropout, removal for ineligibility, or removal for clinical reasons. The only difference in treatment procedure was that significantly less time was devoted to auxiliary sessions in SBFT than in the other two groups, consistent with the family focus of this treatment model.15

Treatment Credibility Measure

Treatment credibility was measured with the treatment credibility analogue developed by Borkovec and Nau,3 which includes the following five items: 1) How logical does this type of treatment seem to you? 2) How confident would you be that this treatment would be successful in eliminating your child's problem? 3) How confident would you be in recommending this treatment to a friend who has a child with a similar problem? 4) How willing are you to let your child undergo this treatment because of his/her problem? and 5) How successful do you feel this type of treatment would be for a problem which is similar to although not exactly like your child's current problem? Each item is evaluated on a five-point Likert-type scale.

The discriminant validity of the treatment credibility analogue has been established insofar as it discriminates treatment from those receiving no-treatment/ placebo control.3,5,7 Previous studies have shown treatment credibility to include only one factor.3,4,26 Confirmatory factor analysis with all items and an examination of scree plots in the present study also indicated the presence of only one factor with high internal consistency (α=0.88 and 0.92 at baseline and the end of treatment, respectively). At intake, one factor explained 63% of the variance, and at the end of treatment a single factor explained 65% of the variance. At both time points, the addition of a second factor increased the variance explained by only 12%, indicating further that one factor was adequate for both periods.

Assessment Variables at Baseline

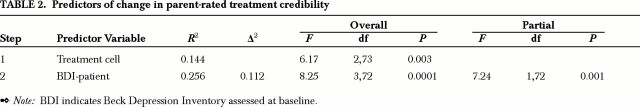

The following variables were assessed as to their influence to predict the change in parent-rated treatment credibility from baseline to the end of treatment (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Demographic and clinical variables.

Clinical Variables: Self-reported depression in subjects was assessed with the BDI.22 Current maternal depression was assessed from the mothers' answers on the BDI. We did not evaluate current paternal depression because only a small number of the fathers were depressed at the time of the study (n=2).

Family Environmental Variables: The caretaking parent reported on the following self-rated family environmental scales: 1) the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ),25 assessing conflicts and negative communication; 2) the Area of Change Questionnaire (ACQ),27 which evaluates desired change in parent-child relationships across specified problem areas; and 3) the Family Assessment Device (FAD),28 which assesses several domains of family climate, including a score of general family functioning. In the present study we used only the General Functioning domain of the FAD (FAD-GF). All questionnaires have been shown to possess good psychometric properties and have been described in detail previously.15

Clinician Variables: The variables examined were gender, age, and years of clinical experience.

Treatment-Related Variables: The following variables were examined as potential predictors of the change in parent-rated treatment credibility: 1) change in self-reported BDI score from baseline to the end of treatment and 2) change in parent-reported CBQ, ACQ, and FAD-GF scores from baseline to the end of treatment.

Assessment Schedule

The scales were assessed at baseline and at the end of treatment (12th to 16th week), and an attempt was made to interview even those subjects who did not finish treatment. According to previous recommendations,4,7 the baseline treatment credibility analogue was rated after the parents were presented with the rationale of the specific treatment to which their children were assigned, but before treatment actually started. In all, 99 patients (92.5%) and 97 of their parents (90.6%) received a final interview. There were no differences among the treatment cells as to proportions with missing data. Ninety-six parents at baseline (89.9%) and 89 at the end of treatment (83.1%) completed the treatment credibility instrument. There were no differences across treatment cells with respect to proportion of parents completing this instrument.

Data Analysis

A stepwise multiple linear regression model was used to identify predictors of the change in parent-rated treatment credibility from pre- to post-treatment. Predictor variables included treatment, baseline, and change scores of patient self-reported BDI and of parent-reported CBQ, ACQ, and FAD-GF; baseline maternal BDI; and therapist-related variables (gender, age, years of clinical experience). The treatment variable was dummy-coded to reflect the three treatment cells, with NST as the reference group. Because we were particularly interested in identifying predictors of the change in treatment credibility above and beyond the effects of treatment, the treatment variable was forced to enter the equation on the first step. The remaining predictor variables were then allowed to enter the equation on subsequent steps.

Alpha was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). We did not use a Bonferroni correction procedure because each of the predictor variables used in this analysis was hypothesized to predict the change in parent-rated treatment credibility.

RESULTS

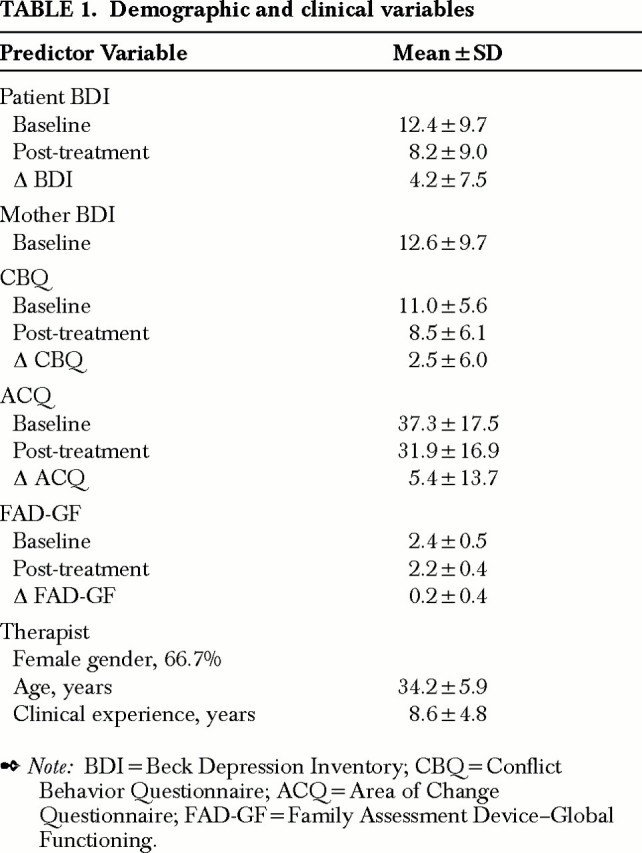

Table 2 presents the results of the stepwise regression analysis. After treatment effects were controlled, patient-reported baseline BDI emerged as the only significant predictor of the change in parent-rated treatment credibility, accounting for 11% of the variance. An examination of the correlation between baseline BDI and change in credibility within each treatment cell showed that the two individual therapies accounted for most of this association (CBT, r=0.38, P=0.03; NST, r=0.47, P=0.02). SBFT was also positively correlated with change in treatment credibility, but the relationship was not statistically significant (r=0.23, P=0.27). A test of the interaction between treatment cell and patient-reported baseline BDI was not significant.

TABLE 2. Predictors of change in parent-rated treatment credibility.

DISCUSSION

The present study represents one of the first controlled attempts to determine what variables influence the perception of treatment among relatives of mental health patients.1 Our results suggest that after controlling for allocation of treatment, only one variable, severity of self-rated patient depression at baseline, predicts the change in parent-rated credibility over time. Specifically, the greater the baseline depression of children treated with CBT and NST (but not SBFT), the more favorable was the change in parent-rated credibility from baseline to the end of treatment.

In findings convergent with other studies of CBT in adolescent depression,29,30 our group has also shown that high levels of depressive symptoms at intake predict poor symptomatic outcome.31 We have furthermore found that the severity of the index depressive episode was a predictor of additional treatment beyond that provided in the clinical trial, both in the acute phase and in the 24-month follow-up period.32 It is unexpected, then, that a greater severity of the child's depression at intake actually predicted a more favorable change in treatment credibility for parents whose children were treated with CBT. Furthermore, patients who are more symptomatic and show greater distress at intake have a more negative perception of their treatment at endpoint.17 We suggest that parents of severely depressed children are likely to regard any improvement as favorable in a treatment setting that focuses on symptomatic improvement, whereas parents of children with mild or moderate depression may seek a more robust treatment effect.

We also found that the severity of the child's depression predicted a more favorable change in the credibility for parents whose children were treated with NST, although this treatment was associated with only a mild improvement of the child's depression. Again, the support of an empathic, concerned, and skilled professional contact in the case of NST may have appealed to parents of more depressed children in the auxiliary sessions provided for family members, even if the treatment did not prove to be highly effective.12,13

In this respect, the lack of influence of severity of depression on the change in parent-rated treatment credibility in the SBFT group may reflect the family- oriented rather than depression-oriented focus of this treatment and the less time devoted to auxiliary sessions with the parents.15 As with NST, family therapy was not found to be as beneficial for depressed children as CBT in our study15 and in other studies.33 However, family therapy may be less appealing to parents of severely depressed children than supportive therapy because in family therapy the focus is primarily on long-standing conflictual areas in the family, and thus parents may particularly feel blamed by the clinician for their children's problems.13

It is not clear why the differential change in depression over time did not predict the difference in the change in parent-rated credibility across the three treatment cells—this, when bearing in mind that parents' perceptions of treatment deteriorated if the children were treated with the two less efficacious interventions (SBFT and NST), compared with CBT. One explanation for this negative finding can be related to the nature of the credibility measure administered. The treatment credibility analogue, being a unidimensional construct, offers only a low range of response choices and assesses only general parental credibility.1 Different specific dimensions of credibility could be differentially associated with the impact of treatment across the three treatment cells.1 Furthermore, although the treatment credibility analogue has been previously used in some clinical populations,6 it has been primarily applied to assess credibility of active treatments versus no-treatment/placebo conditions in nonclinical volunteers.3,5,7 To the best of our knowledge, our study represents the first attempt to evaluate the applicability of this scale in the study of parents of emotionally disturbed adolescents receiving psychotherapy.

It is also noteworthy that family-related and therapist-related variables did not predict the difference in the change of parent-rated credibility from baseline to the end of treatment. We relate these negative findings to the almost ideal conditions in which this study was undertaken. Our families were highly cooperative, this being demonstrated by the very low dropout rate (8 of 107) of children from treatment.15 None of the family functioning variables in our study were found to predict efficacy after 12 to 16 weeks of treatment,31 although family problems at intake did predict the need for additional treatment and recurrence of depression in the 24-month follow-up period.32,34 Perhaps had there been greater family-related problems, these problems would have had more effect on predicting change in parent- rated treatment credibility.2

Furthermore, in the present research-oriented design, therapists across all treatment cells were similarly highly trained, motivated, and supervised; maintenance of treatment integrity was highly structured; and parents received psychoeducation and auxiliary treatment as required.15 The influence of these almost ideal conditions on maximizing credibility4 is reflected in the similarly high baseline parent-rated treatment credibility scores across all treatment cells (mean score of 4.3 to 4.5, where the value of 5 signifies the highest score).15 This finding is also in keeping with the overall high satisfaction levels in studies assessing global patient satisfaction.35 It is possible that the restricted variability of baseline treatment credibility and the ideal treatment setting could have minimized any potential effects of treatment-outcome, family, and therapist-related variables on credibility.4

The main limitation of the study derives from the use of a unidimensional scale to evaluate credibility. Other limitations include the selective nature of the patient and parent samples and of the treatment conditions. The main advantage of the study is its potential to compare parent-rated credibility of two psychotherapies aimed specifically at the treatment of depression15 against a treatment model standardizing the nonspecific aspects of psychotherapy, rather than against a no-treatment control condition.7

We have previously shown that the change from baseline to post-treatment in the parent-rated credibility of the treatment of their depressed offspring was different for family and supportive therapies as compared with cognitive-behavioral treatment. The present study found that baseline self-rated patient depression has the potential to predict this difference. It is recommended that future research include more specific and multidimensional measurements of treatment credibility, evaluated in treatment settings that resemble the more typical community service setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and families for their participation and gratefully acknowledge the following colleagues who provided clinical and technical assistance throughout this study: Robert Berchick, Carl Bonner, Mary Beth Boylan, Marlane Cully, Tom Devereaux, Terry Feinberg-Steinberg, Tom Gigliotti, Denise Harper, Susan Hogarty, Satish Iyengar, Hope Jacobs, Barbara Johnson, Ann Kolar, Maureen Maher, James Matta, Barbara McDonnell, April Miller, Elizabeth Perkins, Randy Phelps, Kim Poling, Matt Scaife, Joy Schweers, Bill Sherman, Jeannie Starzynski, Susan Wesner, and Karen Woodall. This work was supported by Grants MH46500 and MH55123 from the National Institute of Mental Health..

References

- 1.Ruggeri M: Patients' and relatives' satisfaction with psychiatric services: the state of the art and its measurement. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1994; 29:212–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young SC, Nicholson J, Davis M: An overview of issues in research on consumer satisfaction with child and adolescent mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies 1995; 4:219–238 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borkovec TD, Nau SD: Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1972; 3:257–260 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirsch I, Henry D: Extinction versus credibility in the desensitization of speech anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol 1977; 45:1052–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lent RW: Perceptions of credibility of treatment and placebo by treated and quasi-control subjects. Psychol Rep 1983; 52:383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson RA, Borkovec TD: Relationship of client participation to psychotherapy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1989; 20:155– 162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson NS, Baucom DH: Design and assessment of nonspecific control groups in behavior modification research. Behavior Therapy 1997; 8:709–719 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lent RW, Russell RK, Zamostny KP: Comparison of cue-controlled desensitization, rational restructuring, and a credible placebo in the treatment of speech anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol 1981; 49:608–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalman TP: An overview of patient satisfaction with psychiatric treatment. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1983; 34:48–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grella CE, Grusky O: Families of the seriously mentally ill and their satisfaction with services. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:831–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeChillo N: Collaboration between social workers and families of patients with mental illness. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services 1993; 74:104–115 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarico VS, Low BP, Trupin E, et al: Children's mental health services: a parent perspective. Community Ment Health J 1989; 25:313–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins BG, Collins TM: Parent-professional relationship in the treatment of seriously emotionally disturbed children and adolescents. Social Work 1990; 35:522–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeChillo N, Koren PE, Schultze KH: From paternalism to partnership: family and professional collaboration in children's mental health. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1994; 64:564–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, et al: A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family and supportive treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:877–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attkisson CC, Zwick R: The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning 1982; 5:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carskaddon DM, George M, Wells G: Rural community mental health consumer satisfaction and psychiatric symptoms. Community Ment Health J 1990; 26:309–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall GN, Hays RD, Mazel R: Health status and satisfaction from health care: results from the medical outcomes study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:380–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brannan AM, Hefflinger CA: Parental satisfaction with their children's mental health service. Paper presented at Building on Family Strength Conference, Portland, OR, 1994

- 20.Hall JA, Milburn MA, Epstein AM: A causal model of health status and satisfaction with medical care. Med Care 1993; 31:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987

- 22.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG: Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988; 8:77–100 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al: Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, Guilford, 1979

- 24.Alexander J, Parsons BV: Functional Family Therapy. Monterey, CA, Brooks/Cole, 1982

- 25.Robin AL, Foster SL: Negotiating Parent-Adolescent Conflict: A Behavioral-Family Systems Approach. New York, Guilford, 1989

- 26.Rokke PD, Lall R: The role of choice in enhancing tolerance to acute pain. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1992; 16:53– 65 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacob T, Seilhamer RA: Adaption of the Areas of Change Questionnaire for parent-child relationship assessment. American Journal of Family Therapy 1985; 13:28–38 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein N, Baldwin L, Bishop DS: The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther 1983; 9:171–180 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke G, Hops H, Lewinshon PM, et al: Cognitive- behavioral group treatment of adolescent depression: prediction of outcome. Behavior Therapy 1992; 23:341–354 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayson D, Wood A, Kroll L, et al: Which depressed patients respond to cognitive-behavioral treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brent DA, Kolko D, Birmaher B, et al: Predictors of treatment efficacy in a clinical trial of three psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:906–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brent DA, Kolko D, Birmaher B, et al: A clinical trial for adolescent depression: predictors of additional treatment in the acute and follow-up phases of the trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrington R, Kerfoot M, Dyer E, et al: Randomized trial of a home-based family intervention for children who have deliberately poisoned themselves. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:512–518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kolko D, et al: Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruggeri M, Dall'Agnolla R: The development and the use of the Verona Expectations for Care Scale (VECS) and the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale (VSSS) for measuring expectations and satisfaction with community-based psychiatric services in patients, relatives and professionals. Psychol Med 1993; 23:511–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]