Abstract

Patients with dysthymia have been shown to respond to treatment with antidepressant medications, and to some degree to psychotherapy. Even patients successfully treated with medication often have residual symptoms and impaired psychosocial functioning. The authors describe a prospective randomized 36-week study of dysthymic patients, comparing continued treatment with antidepressant medication (fluoxetine) alone and medication with the addition of group therapy treatment. After an 8-week trial of fluoxetine, medication-responsive subjects were randomly assigned to receive either continued medication only or medication plus 16 sessions of manualized group psychotherapy. Results provide preliminary evidence that group therapy may provide additional benefit to medication-responding dysthymic patients, particularly in interpersonal and psychosocial functioning.

Keywords: Dysthymia, Group Therapy, Pharmacotherapy

Dysthymic disorder is a prevalent and debilitating disorder (3% to 6% lifetime prevalence)1,2 that is associated with high medical and psychiatric comorbidity.3–6 Recent reviews7–9 have described the potential benefits of combined psychotherapy and psychopharmacology for chronic depression and the need for more research in this area.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Studies of Monotherapies for Chronic Depression

Psychopharmacology studies of chronic depression, both “double depression” (concurrent dysthymic disorder and major depression)10,11 and “pure dysthymia,”12,13 have demonstrated significant reduction of depressive symptoms following medication treatment. Dysthymic patients generally function below the level characteristic of community populations,5 although recent studies have provided evidence that antidepressants may improve social-vocational functioning.14,15 In many studies, the preponderance of dysthymic patients have single marital status, suggesting impaired development of intimate relationships, and people with dysthymia often have impaired vocational functioning.16 Community treatment studies4,7 confirm that chronic depression, whether treated or not, is associated with a high degree of psychological morbidity. Furthermore, significant symptoms and behavioral patterns may persist after medication response. These include social withdrawal, low self-esteem, poor communication skills, hopelessness, negative cognitive style, lack of motivation, and other difficulties that suggest ongoing impairment in the patient's social relationships and interpersonal functioning.3,11

Various psychotherapy approaches17 have attempted to address the psychosocial impairments associated with chronic depression, although most of these approaches have been studied primarily in major depression rather than dysthymic disorder.

Cognitive Therapy (CT) is the best-studied psychotherapy for chronic depression. Reports of mostly brief individual cognitive-behavioral therapies of dysthymia18–20 suggest that patients respond to this approach, showing a reduction of depressive symptomatology roughly equivalent to that seen in controlled antidepressant trials. In Dunner's recent study of 31 dysthymic subjects,20 CT had a comparable effect to fluoxetine in the treatment of dysthymic disorder, with a less robust degree of response to either treatment than that found in major depression.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), a form of short-term psychotherapy developed by Klerman and colleagues, has been shown to be effective in treating depressed outpatients.21,22 Recently Markowitz23 provided evidence that individual IPT may be effective in the treatment of dysthymic patients previously nonresponsive to an antidepressant trial.

Cognitive-Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP), a treatment developed by McCullough,24 combines cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal interventions in a three-phase treatment specifically designed for dysthymia. Its goals are to attempt to teach patients to accept responsibility for their depression and to “achieve and maintain mood control by enacting adaptive daily living strategies.”

Group therapy for chronically depressed patients has not been adequately tested for efficacy, and the published findings conflict. In the 1980s, studies in major depression showed mixed results, with some25–27 reporting benefits of group CT. It is of note that these studies were not specific to dysthymic disorder. Most cognitive group therapies focus on symptom reduction and use the group setting to address interpersonal dysfunction or to conduct in vivo practice of social skills, which may be particularly crucial in treating dysthymic disorder.

Given these conflicting findings, it is possible that a more effective group approach could be developed for dysthymic disorder. For patients with other disorders, such as borderline personality disorder28 or comorbid schizophrenia and substance dependence,29 highly structured interventions including group therapy have improved outcome in comparison to standard treatment. Such an approach would address not only depressive symptoms and neurobiological knowledge about depression,30 but also psychosocial dysfunction, residual symptoms, and common comorbidities.

Studies of Combined Treatment for Mood Disorders

In the following review of research into combined treatment of mood disorders, three points are important to note. First, most studies have been on major depression (either acute or chronic), with virtually no controlled studies on combined treatment for dysthymia.7 Second, many studies have focused primarily on remission of acute symptoms rather than on a broad range of outcome variables that would be of concern with dysthymic patients, such as interpersonal and social functioning. And third, the literature on combined treatments centers on individual rather than group therapies.

Potential goals of combined treatment (as summarized by Thase31) include reducing rates of relapse and recurrence; improving adherence to medication; reducing residual symptoms; dampening pathological personality traits; enhancing the ability to deal with stressors; strengthening social networks; and improving problem-solving skills. Pava et al.32 have suggested that CT and pharmacotherapy are potentially beneficial in the treatment and prophylaxis of depression; they believe that the benefits for CT will be found primarily during the continuation phase, particularly in preventing relapse and treating residual symptoms. This is an additive model of combined treatment, in which the treatments “exert independent effects on different problems, thereby broadening the therapeutic impact” (p. 213).

Like the literature on group therapy, the recent research on combined treatments in major depression has produced equivocal results (see reviews9,33 relevant to chronic depression). Thase's 1997 mega-analysis9 suggested that combined treatment could be most effective for patients with severe and recurrent depression, and less beneficial in milder depressions (though potential benefit in pure dysthymia was not addressed). Individual studies32–36have shown that combined treatment was more effective34,35 and prevented relapse better36 than pharmacotherapy alone. In contrast, Hollon et al.37 found no difference. Recently, a large, well-designed multicenter study of McCullough's CBASP24 compared with nefazodone38 for chronic nonpsychotic major depressive disorder demonstrated the superiority of combined treatment, with a response rate of 73% for combined treatment versus 48% for medication or CBASP alone.

Summary

Pharmacotherapy has been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of dysthymia, although residual symptoms, which are associated with relapse, often persist. Individual forms of cognitive and interpersonal psychotherapy have been demonstrated to be effective in treating dysthymia. Treatment of major depression with individual cognitive therapy has been shown to reduce rates of relapse when compared with placebo and medication-alone treatments. Studies of the efficacy of group psychotherapy have produced mixed results, although no controlled studies have been conducted in dysthymia. Combined treatments have also received little attention in dysthymia, and even less attention has been devoted to combined group psychotherapy and medication in any population of mood-disordered patients.

A MODEL FOR GROUP THERAPY OF DYSTHYMIA: CIGP-CD

The rationale for developing a model of group therapy in treatment of dysthymia has several components. The high prevalence of the disorder and the potential cost-effectiveness of group treatment are practical reasons for using groups. Common characteristics of the disorder, such as social isolation, demoralization, and poorly developed social skills might be addressed effectively in a group setting. Groups are well suited for psychoeducation about psychiatric disorders, treatments, relapse prevention, and coping strategies. The group might provide an optimal setting in which behavioral changes could be modeled and observed in others. Maladaptive cognitive and interpersonal patterns may often be more effectively addressed by peers in a group than by psychotherapists in an individual therapy setting. Furthermore, a sequential treatment protocol in which medication response is attained first and psychotherapy is added later (in order to address residual symptoms, psychosocial deficits, relapse prevention, etc.) may have advantages in terms of both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

On the above basis, we developed a manualized group therapy model, Cognitive-Interpersonal Group Psychotherapy for Chronic Depression (CIGP-CD), which combines cognitive and interpersonal approaches. Groups consist of approximately 10 patients and meet on a weekly basis for 16 weeks for 1½-hour sessions. Groups are designed to be co-led by two therapists. In group meetings, patients are educated about the symptomatology and common consequences of dysthymic disorder. They are also educated about the effects and limitations of medication response. Patients are encouraged to work actively to confront persistent or recurrent symptoms during the early stages of medication-induced euthymia, analogous to the way an alcohol abuser may deal with cravings or “slips” in the early stages of sobriety.39

Besides psychoeducation, groups emphasize the importance of members' adapting behavioral strategies to increase a sense of efficacy and control.30–32 They address interpersonal difficulties that are pervasive in the clinically depressed, such as social isolation and low self-esteem. Therapists encourage group members to observe each other's behaviors in group, have them take part in exercises to practice more open communication patterns, and encourage them to challenge one another's long-standing pessimistic and catastrophic beliefs.

Prevention of relapse is a major treatment goal. Research by Frank and co-workers40,41 suggests that monthly maintenance IPT can buffer against symptomatic relapse or recurrence after the termination of drug treatment in highly recidivistic major depression patients. Also, as mentioned previously, studies of patients with major depression have found that CT, with or without medication, resulted in lower relapse rates at follow-up than medication alone42,43 or placebo.44

We report here on the results of a randomized, prospective, open-label two-cell trial of fluoxetine alone versus fluoxetine plus CIGP-CD in outpatients diagnosed with DSM-III-R dysthymia. The purpose was to assess the benefits of adding group therapy to medication treatment in a sample of medication-responsive dysthymic patients. The primary hypothesis was that combined treatment would lead to a broader spectrum of improvement than medication alone at termination (24 weeks). Specifically, patients receiving medication treatment alone were hypothesized to show significant improvement in symptoms, moderate improvement in global psychosocial functioning, and minimal improvement in personality functioning. Combined treatment was hypothesized to lead to significant improvement in all three areas. A secondary hypothesis was that gains achieved by termination would be maintained at follow-up (week 36) for combined treatment subjects, whereas medication-alone subjects would have a high degree of relapse.

METHODS

Subjects

The study was performed at a large urban tertiary care teaching hospital. Inclusion criteria were 1) age between 21 and 65 years; 2) meeting DSM-III-R criteria for dysthymia, primary type, early onset; 3) a score of 14 or greater on the 21-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D) at baseline; and 4) discontinuation of all psychotropic medications at least 6 weeks prior to study entry. Exclusion criteria included 1) DSM-III-R diagnoses of organic mental syndromes, major depression (current or partially remitted), bipolar disorder, severe cyclothymia, any psychotic disorder, or severe borderline personality disorder; 2) any diagnosis of substance or alcohol abuse or dependence within the past 6 months; 3) a primary diagnosis within the past 6 months of panic disorder, severe generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder; 4) pregnant or nursing women; 5) medical illness, either life-threatening or assessed as a probable cause of dysthymia; 6) currently undergoing another psychotherapy; and 7) at serious suicidal risk.

Our sample consisted of 20 male and 20 female subjects diagnosed with DSM-III-R dysthymia. Men and women were evenly randomized (by chance) to each treatment condition. Most subjects were employed: 70% (n=28) full-time, 17.5% (n=7) part-time; 12.5% (n=5) were unemployed. The rationale and procedures of the study were explained to the subjects who met admission criteria; all subjects gave written informed consent.

Procedures

After initial assessment, all subjects were given an 8-week fluoxetine trial. Patients received fluoxetine beginning at 10 mg/day, increasing to 20 mg/day within 7 to 10 days, and thereafter adjusted clinically according to symptomatology and side effects to a maximum dose of 80 mg/day. Medication visits lasted 15 to 20 minutes and were limited to discussion of symptoms, medication, and side effects. Psychiatrists were instructed not to engage in psychotherapy, counseling, or supportive interventions.

Medication visits were scheduled for weeks 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 (mid-phase), 12, 16, 20, 24 (termination), 28, 32, and 36 (follow-up). At each of these visits, clinician ratings on Ham-D, CDRS, and CGI were conducted. Patients completed self-report scales at weeks 0, 8, 24, and 36 and completed the BDI at each medication visit. (All rating instruments are described below under Measures.)

Patients who showed at least partial medication response by week 8 (≥40% decrease in Ham-D and a CGI-I score of 1 [very much improved] or 2 [much improved]) were randomized to two study samples, one receiving medication alone, the second receiving 16 sessions of manualized group psychotherapy in addition to medication. Group psychotherapists were two clinical psychology Ph.D. students with extensive psychotherapy training. Prior to starting groups, they met on a weekly basis with a senior psychiatrist supervisor (D.J.H.) for two months to review the conduct of treatment. Treatment was conducted according to the CIGP-CD treatment manual (D.J. Hellerstein, S.A.S. Little, L.W. Samstag, J.C. Muran: “CIGP-CD Treatment Manual,” Mood Disorders Research Unit, Beth Israel Medical Center; unpublished manuscript). Sessions were audiotaped and reviewed in weekly supervision meetings for adherence to the manual.

Active treatment (both medication and group therapy) ended approximately 24 weeks after the initiation of medication. Because of scheduling difficulties, some subjects received more than 24 weeks of medication so that medication would not be discontinued before the group treatment was complete. Mean (±SD) duration of medication treatment was 28.0±4.8 weeks for medication-alone patients and 27.2±5.1 weeks for combined treatment patients, not significantly different. At the end of the active phase of treatment, medication was tapered and discontinued over a period of 1 to 3 weeks. Patients remained in the study protocol until the follow-up assessment at week 36 and were monitored at weeks 28 and 32 by the treating psychiatrist for signs of adverse treatment effects or the appearance of serious or life-threatening symptoms, such as suicidality.

Treatment outcome was assessed at week 24 to determine recovery rates and at week 36 to determine the rate of relapse. These assessments included psychiatric assessment of symptomatology and a variety of psychometric inventories, described below.

There was a high degree of treatment retention, with 85% (17/20) of medication patients and 90% (18/ 20) of combined treatment patients completing 24-week treatment. Mean (±SD) fluoxetine dose at week 24 was 38.75±18.93 mg/day for the medication-alone sample and 37.36±17.27 mg/day for the combined treatment sample.

Measures

Treatment outcome was assessed in three areas by using a variety of measures that included ratings from three perspectives: patient, clinician, and observer. The areas of functioning assessed were 1) depressive syndrome/symptomatology, 2) personality functioning (interpersonal functioning and cognitive style), and 3) global psychosocial functioning. Personality functioning was defined for purposes of this study as a heterogeneous domain comprising quality of interpersonal relationships and cognitive style.

Symptomatology Measures: These included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-I,45 SCID-II46), with the dysthymia module rated at termination and follow-up, regarding symptoms during the previous 2-week period; the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D);47,48 the Cornell Dysthymia Rating Scale (CDRS);49 and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).50

Personality Measures: These included the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP),51 a self-report inventory (for each patient, the subscale that was rated as the most problematic at intake was identified, and the change in this subscale over time was used as an ipsative measure of personality change); the Life Orientation Test (LOT),52 a self-report measure of dispositional optimism; and the Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ),53 a self-report scale measuring internality, globality, and stability of attributions. The Composite Negative subscale (ASQ-CONEG) assesses attributions for negative events, which have been shown to be correlated with and predictive of depression.54 Higher scores indicate more internal, global, and stable attributions.

Measures of Global Functioning: These included the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF);55 the Clinical Global Impressions Scale–Global Improvement Rating (CGI-I);56 and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS),57 a self-report measure of subjective life satisfaction.

Raters were trained for reliability on the Ham-D, GAF, CGI, CDRS, and SCID and had participated in previous dysthymia studies through the Mood Disorders Research Unit.

Statistical Methods

Power estimation was based on expected differences on measures that were hypothesized to be affected by the group treatment: Global Functioning and Personality Functioning. We used an estimate of a medium effect size and determined that a sample size of between 35 and 50 would be adequate for 80% power. Since psychotherapy group size is approximately 10 people, we chose a sample size for this pilot study of 20 combined treatment patients and 20 medication-alone patients. Data were analyzed to assess differences in symptoms and functioning between the two different treatment groups at three assessment points: prior to initiation of treatment (intake; week 0), immediately after completion of treatment (termination; week 24), and 12 weeks after treatment ended (follow-up; week 36).

We performed t-tests to test for significant differences between the treatment groups at intake. Univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) using SPSS version 9.0 were conducted to assess group differences at termination and follow-up, covarying CGI-Severity scores at intake to control for differences in initial severity of illness. Reliable change (RC) scores58 and cutoff scores were used to classify patients as “improved” at termination and follow-up, with RC scores used on scales where no preexisting cutoff score or norm was available. The proportion of patients in each treatment cell classified as improved was examined. Reliable change scores assess the significance of change from pre- to post-test based on the standard deviation and test-retest reliability of the measure.

The proportion of patients in each treatment condition who improved in each domain of functioning at termination and follow-up was examined. Improvement was defined by use of cutoff scores and RC scores. Criteria for improvement in the Symptomatology domain were 1) scores within normal range on three measures of depression (Ham-D≤7, BDI≤10, and CDRS≤20), and 2) absence of a diagnosis of dysthymia on the SCID. Criteria for improvement in the Global Functioning domain were 1) GAF score≥70, and 2) CGI-I scores of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved). Criteria for improvement in the Personality Functioning domain were RC scores with an absolute value greater than 1.96 on 1) the IIP and 2) the LOT. These criteria were applied to termination and follow-up data separately. Patients scoring in the given range were classified as improved on that measure at that assessment period. Z-tests were performed to test for differences between the proportions for the two groups.

Missing Data

Subjects who discontinued treatment prior to the evaluation of medication effectiveness and initiation of the group treatment at week 8 were not included in subsequent analyses because the main thrust of the analyses was comparisons related to the additive impact of group therapy to effective medication treatment. For the 35 subjects who were evaluated at week 8, all of whom continued to week 24, missing data points at follow-up were handled in the following manner. The Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) method was used for the physician-rated scales. Thus, the most recent ratings were used for those subjects who missed the week 36 follow-up assessment visit (n=7). Specifically, the following visits were used as follow-up data: week 28 (n=3), week 30 (n=2), and week 32 (n=2). However, because of the lack of interim assessments using self-report assessments (i.e., there were no data collected between termination and follow-up for these scales), the LOCF method was not used for these scales. Thus, for the Personality and Global Functioning analyses, which relied on self-report data, the sample was smaller at follow-up than for the Symptomatology analyses, which used the LOCF method.

RESULTS

Description of Treatment Sampleat Baseline and Midphase

Forty subjects were enrolled into the study, 20 men and 20 women. The sample had an average age (mean±SD) of 45.10±9.76 years, were primarily Caucasian (n=35), employed full-time (n=28), and either single (n=18) or married (n=12). Approximately half of the sample had previous major depressive episodes (n=19, 47.5%), with the two treatment groups evenly represented (combined: n=8, medication: n=11). The average number of major depressive episodes (mean±SD) was 3±2.51 (combined: 3.17±3.43; medication: 2.89±1.90). The majority of the sample (n=32, 80%) had had previous individual psychotherapy; the average number of months in therapy was 27.75±25.99 (combined: 21±20.23; medication: 33.66±29.53), and this history was also evenly split between treatment conditions (16/16). In addition, 10 of the subjects had previous group therapy experience, and this also was evenly split (5/5).

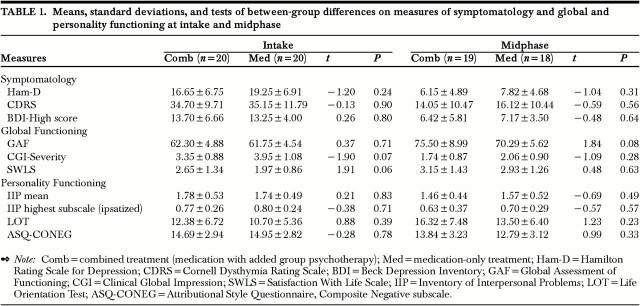

At intake, the two treatment groups showed a trend toward significant differences on two measures: CGI-Severity and SWLS. The medication-only group received higher severity ratings and lower life satisfaction ratings on the SWLS than did the combined-treatment group. The means, standard deviations, and significance tests are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Means, standard deviations, and tests of between-group differences on measures of symptomatology and global and personality functioning at intake and midphase.

After 8 weeks of medication, subjects were again assessed on all scales. The means, standard deviations, and significance tests are presented in Table 1. The t-tests for independent samples revealed no significant differences between the two groups on any measure. This was expected, since both groups had received identical treatment up to this point.

Termination

There was a high degree of treatment retention, with 85% (17/20) of medication patients and 90% (18/ 20) of combined treatment patients completing 24-week treatment. One of the medication-only subjects failed to show a significant response to the 8-week trial of medication and thus was not entered into the second phase of the study; the other 4 noncompleters dropped out of treatment prior to the midphase assessment. In addition, 10% (n=2) of subjects in the group therapy (5% of all patients) were noncompliant with attending group sessions (noncompliance was defined as <75% attendance). Of those who reached week 24 and provided data at that time point, 74% also completed follow-up assessments, a loss of 26% of the sample from termination to follow-up.

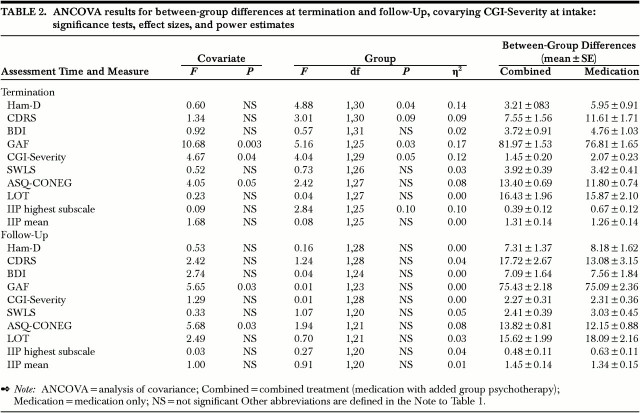

Univariate ANCOVAs for each measure are presented in Table 2, along with the adjusted means and standard errors to show the direction of effect. Significant differences between the treatment groups were found on three measures, with combined treatment patients showing better functioning at termination than the medication-only patients on the Ham-D, GAF, and CGI-Severity scales. There were also nonsignificant trends toward lower scores for the combined treatment on the CDRS and the IIP highest subscale. No differences were found on the BDI, LOT, IIP mean score, CONEG, or SWLS. Six of the 10 measures showed effect sizes (ES, expressed as eta-square or η2) in the medium to large range, using Stevens's59 operational definitions (small ES: η2=0.01, medium ES: η2=0.06; large ES: η2=0.14). Eta-square is interpreted as the proportion of the variability in scores attributable to the differences between the two treatments. Therefore, we found that 14% of the variability in Ham-D scores is attributable to treatment differences. Similarly, 9% of the CDRS, 12% of the CGI-S, 17% of the GAF, 10% of the IIP highest scale, and 8% of the CONEG scores is attributable to treatment differences. The other scales (LOT, IIP mean score, SWLS, BDI) showed effect sizes in the small range.

TABLE 2. ANCOVA results for between-group differences at termination and follow-up, covarying CGI-Severity at intake: significance tests, effect sizes, and power estimates.

Follow-up

ANCOVAs were again conducted on follow-up data, similar to the termination analyses (see Table 2). Adjusted means are presented in Table 2 to show the direction of effect. No significant group differences emerged for any of the follow-up measures. The adjusted means were quite similar for the two groups, and the effect sizes were often less than 0.01. The only notable exception is the CDRS, where the combined treatment group showed a higher mean score (17.72, SE=2.67) than did the medication-only treatment group (13.08, SE=3.15). However, it should be kept in mind that the effect size is in the small range (η2=0.04), and the difference is not statistically significant.

Percentage Improved at Termination and Follow-up

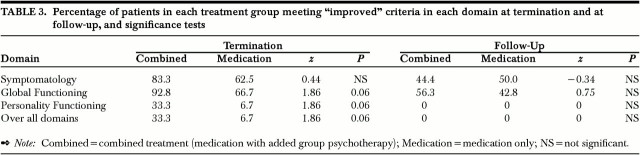

The percentages of patients in each treatment group meeting criteria for improvement in individual domains of functioning as well as across all domains of functioning are presented in Table 3. At termination, the combined treatment showed greater proportion of improved patients in each domain of functioning, as well as in the proportion of patients improved in all of the three domains. Significance tests reveal that the proportions showed a trend toward significance for Global Functioning, Personality Functioning, and all domains. At follow-up, differences were smaller, with roughly half of the patients in both groups showing improvement in Symptomatology and Global Functioning. None of the patients in either treatment showed improvement in the area of Personality Functioning. Tests of the difference between proportions were all nonsignificant, indicating no difference in improvement rates between the two treatment groups at follow-up.

TABLE 3. Percentage of patients in each treatment group meeting "improved" criteria in each domain at termination and at follow-up, and significance tests.

Response and Remission

The two study samples were evaluated for response and remission at termination and follow-up. Response was defined as a greater than 50% decrease in Ham-D and a score of 1 or 2 on the Clinical Global Impressions Improvement subscale (very much improved or much improved). By these criteria, 89% (16/18) of combined treatment subjects responded at termination, versus 76% (13/17) of medication-only patients. At follow-up, 61% (11/18) of combined treatment patients and 40% (6/15) of medication-only patients were responders. In these small samples, differences were not statistically significant. Remission was defined as Ham-D item #1 (depressed mood) score=0 and no longer meeting DSM-IV criteria for dysthymia. At termination, 82% (14/17) of combined treatment and 63% (10/16) of medication-only subjects were in remission, and at follow-up, 31% (4/13) and 50% (6/12), respectively, were in remission. Again, there was no statistically significant difference between groups.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this small pilot study was to determine whether adjunctive group psychotherapy would lead to additional benefits in dysthymic patients who had already shown a response to an SSRI antidepressant medication. Our findings suggest the possibility that there may indeed be additional benefit to combined treatment (see Table 2). At the end of treatment (i.e., at termination), significant differences favoring the combined treatment were found on some symptom measures (Ham-D) and general functioning measures (CGI-S and GAF). Other measures (CDRS, IIP-high score) showed differences at the trend level and demonstrated medium to large effect sizes, with combined treatment subjects showing better functioning in these areas than medication-only treated subjects. Furthermore, 33.3% of patients in combined treatment meet rigorous criteria for improvement in symptomatology, global functioning, and personality variables, whereas only 6.7% of patients treated with medication alone meet these criteria. Given the high degree of impairment of chronically depressed individuals, and the importance of finding treatments that have a broad spectrum of efficacy, these preliminary findings during the active treatment phase are encouraging. It would be important to confirm them in a larger study with sufficient sample size to demonstrate statistical significance, given the medium-to-large effect sizes of this study.

Our findings are consistent with those of Keller et al.,38 who reported from a large multicenter study that combined treatment was indeed more efficacious than medication alone in the treatment of chronic nonpsychotic major depression. In their study, an individual psychotherapy treatment (McCullough's CBASP24) and nefazodone were tested alone and together in the treatment of chronic major depression. Combined treatment led to a greater degree of symptom responsiveness. Effects on psychosocial functioning have not yet been reported from that study, to our knowledge, but would be important to assess. CBASP has been designed for the individual therapy setting, and one interesting question would be whether the modality of individual or group therapy is more effective in providing additional benefit.

Despite the additional improvement after 24 weeks of treatment, additional benefits disappeared at follow-up (after patients had discontinued all treatment). ANCOVAs at follow-up showed no significant differences between groups and very small effect sizes on nearly all measures. There are a number of possible explanations for these findings. The initial improvement of combined treatment may be transitory and may disappear at follow-up regardless of the treatment approach. Alternatively, patients in combined treatment may have an increased vulnerability after 6 months of treatment as they begin to make changes in long-standing interpersonal and functional patterns. The simultaneous ending of two types of treatment (medication and psychotherapy) may be a stress that can trigger relapse. Perhaps remission could be better maintained by continued antidepressant medication treatment after completion of group therapy, or by continuing group therapy while medication is tapered.41,60 These findings may also suggest a need for changes in the group therapeutic approach, with a stronger focus on relapse prevention.

PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

Clearly the results of this study are preliminary, and conclusions must be tentative. Limitations include the small sample size, the lack of an untreated control group or a psychotherapy-only treatment group, and the lack of blinding for medication discontinuation. Although ratings from clinicians, patients, and observers were included, there were no blinded raters. The sequential design of the study (all patients treated with medication, then half randomized to receive additional group therapy) is only one of many possible designs for combining psychotherapy and medication. It is possible that group therapy alone might have provided a similar degree of response to that obtained by combined treatment.

Combined treatment studies of chronic depression may have both practical and theoretical importance. At a practical level, they may provide guidance for the ways medication and psychotherapy treatments can best be combined. The development of effective treatments that alleviate not only the symptomatology but also the psychosocial morbidity of chronic depression would have important public health implications. At a theoretical level, such studies may help to illuminate the psychological and physiological mechanisms through which change takes place when medication and psychotherapy are combined.

The data presented here suggest that a combined medication and group therapy treatment model that targets long-standing psychosocial impairment associated with chronic depression is a feasible one. As mentioned above, at the time of termination (week 24), patients in both treatment groups had improved significantly on a broad range of measures. Patients in combined treatment demonstrated significant improvement on a variety of symptom and interpersonal functioning measures, with greater improvement on some measures than was found with medication treatment alone. The results suggest the need for more extensive studies of the efficacy of combined medication and group therapy for this disorder, with a larger sample size and a more rigorous design that would include blinded raters and a randomized medication continuation versus discontinuation follow-up phase.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Eli Lilly Company. Findings were previously presented at the American Psychiatric Association 150th Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, May 1997.

References

- 1.Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, et al: The epidemiology of dysthymia in five communities: rates, risks, comorbidity, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:815–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller MB:. Dysthymia in clinical practice: course, outcome and impact on the community. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89(suppl 383):24–34 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, et al: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leader JB, Klein DN: Social adjustment in dysthymia, double depression and episodic major depression. J Affect Disord 1996; 37:91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henk HJ, Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, et al: Medical costs attributed to depression among patients with a history of high medical expenses in a health maintenance organization. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:899–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paykel ES: Psychological therapies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89(suppl 383):35–41 [PubMed]

- 8.Keller MB, Hanks DL, Klein DN: Summary of the DSM-IV Mood Disorders Field Trial and issue overview. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:1–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thase ME, Greenhouse JB, Frank E, et al: Treatment of major depression with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmacotherapy combinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1009– 1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kocsis J, Frances A, Voss C, et al: Imipramine for treatment of chronic depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:253–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller MB, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RM, et al: The treatment of chronic depression, part 2: a double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline and imipramine. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:598– 607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellerstein DJ, Yanowitch P, Rosenthal J, et al: A randomized double-blind study of fluoxetine versus placebo in treatment of dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1169–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thase ME, Fava M, Halbreich U, et al: A placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial comparing sertraline and imipramine for the treatment of dysthymia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:777–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocsis JH, Sutton BM, Frances AJ: Long-term follow-up of chronic depression treated with imipramine. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:56–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kocsis JH, Zisook S, Davidson J, et al: Double-blind comparison of sertraline, imipramine, and placebo in the treatment of dysthymia: psychosocial outcomes. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:390–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman RA: Social impairment in dysthymia. Psychiatric Annals 1993; 23:632–637 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markowitz J: Psychotherapy of dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1114–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harpin R, Liberman R, Marks I, et al: Cognitive-behavior therapy for chronically depressed patients: a controlled pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1982; 170:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stravynski A, Shahar A, Verreault R: A pilot study of the cognitive treatment of dysthymic disorder. Behavioural Psychotherapy 1991; 4:369–372 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunner DL, Schmaling KB, Hendrickson H, et al: Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in the treatment of dysthymic disorder. Depression 1996; 4:34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klerman G, Weissman M, Rounsaville B, et al: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984

- 22.Elkin I, Shea M, Watkins J, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:971–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz J: Psychotherapy of the postdysthymic patient. J Psychother Pract Res 1993; 2:157–163 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCullough J: Psychotherapy for dysthymia: a naturalistic study of ten patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:734–740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro J, Sank L, Shaffer C, et al: Cost effectiveness of individual vs. group cognitive behavior therapy for problems of depression and anxiety in an HMO population. J Clin Psychol 1982; 38:674–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rush A, Watkins J: Group versus individual cognitive therapy: a pilot study. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1981; 5:95–103 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wierzbicki M, Bartlett T: The efficacy of group and individual cognitive therapy for mild depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1987; 11:337–342 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, et al: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1771–1776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellerstein DJ, Rosenthal RN, Miner CR: Integrated outpatient treatment for substance-abusing schizophrenics: a prospective study. Am J Addict 1995; 4:33–42 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shuchter SR, Downs N, Zisook S: Biologically Informed Psychotherapy for Depression. New York, Guilford, 1996

- 31.Thase ME: When is the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy likely to be the treatment of choice for patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Depressive Disorders 1997; 2:8–9 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pava JA, Fava M, Levenson JA: Integrating cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of prophylaxis of depression: a novel approach. Psychother Psychosom 1994; 61:211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markowitz JC: Psychotherapy of dysthymic disorder, in Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Depression, edited by Kocsis JH, Klein DN. New York, Guilford, 1995

- 34.Blackburn IM, Bishop S, Glen AIM, et al: The efficacy of cognitive therapy in depression: a treatment trial using cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy, each alone and in combination. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 139:181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy GE, Simons AD, Wetzel RD, et al: Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy singly and together in the treatment of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fava GA, Grandi S, Zielezny M, et al: Cognitive behavioral treatment of residual symptoms in primary major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1295–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Evans MD, et al: Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: singly and in combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:774–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al: A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1462–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse Prevention. New York, Guilford, 1985

- 40.Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, et al: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Wagner EF, et al: Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment of recurrent depression: contributing factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1053– 1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blackburn IM, Eunson KM, Bishop S: A two-year naturalistic follow-up of depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy, pharmacotherapy, and a combination of both. J Affect Disord 1986; 10:67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans MD, Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, et al: Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:802–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simons AD, Murphy GE, Levine JE, et al: Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: sustained improvement over one year. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Patient Edition (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990

- 46.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis II Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990

- 47.Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 25:56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams JBW, Link MJ, Rosenthal NE, et al: Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorders Version (SIGH-SAD), revised edition. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1994

- 49.Mason BJ, Kocsis JH, Leon AC, et al: Measurement of severity and treatment response in dysthymia. Psychiatric Annals 1993; 23:625–631 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL: Construction of circumplex scales for the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. J Pers Assess 1990; 55:521–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheier MF, Carver CS: Optimism, coping and health: assessment and implications of generalized expectancies. Health Psychology 1985; 4:219–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seligman MEP, Abramson LY, Semmel A, et al: Depressive attributional style. J Abnorm Psychol 1979; 88:242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seligman MEP, Castellon C, Cacciola J, et al: Explanatory style change during cognitive therapy for unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol 1988; 97:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987, pp 230–233

- 56.Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: (publ no ADM 76-338). Rockville, MD, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976

- 57.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, et al: The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess 1985; 49:71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacobson NS, Truax P: Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stevens JP: Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 3rd edition. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1996

- 60.Jarrett RB, Kraft D: Prophylactic cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder. In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice 1997; 3:65–79 [Google Scholar]