Abstract

Studies of the therapeutic alliance in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have varied in their results, necessitating a deeper understanding of this construct. Through an exploratory factor analysis of the alliance in CBT, as measured by the Working Alliance Inventory (shortened, observer-rated version), the authors found a two-factor structure of alliance that challenges the commonly accepted one general factor of alliance. The results suggest that the relationship between therapist and client (Relationship) may be largely independent of the client's agreement with and confidence in the therapist and CBT (Agreement/ Confidence), necessitating independent measures of these two factors, not one measure of a general alliance factor.

Keywords: Alliance, Therapeutic; Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; Rating Instruments

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has become one of the most often practiced treatments for depression in the course of the past two decades, and it has been found to be an effective treatment of depression in most efficacy studies.1 It aims to alleviate depression through the direct modification of the clients' irrational and negative beliefs.

The therapeutic alliance is believed by many to be critical for success in all types of psychotherapy.2 Although the importance of alliance in counseling and psychotherapy is generally accepted, the definition of the construct has varied greatly.3 Even though no generally accepted definition of alliance has been offered, studies continue to look at this construct as an integral therapeutic component of psychotherapy. The often-cited meta-analysis by Horvath and Symonds4 shows a meaningful correlation between alliance and treatment outcome, and the more recent meta-analysis by Martin et al.5 shows a moderate but consistent relationship of alliance and outcome across 79 studies.

A popular definition of the therapeutic alliance is that proposed by Bordin.6 He defined alliance as consisting of three related components: 1) client and therapist agreement on Goals of treatment, 2) client and therapist agreement on how to achieve the goals (Task agreement), and 3) the development of a personal Bond between the therapist and client. This conceptualization implies a factor structure characterized by one general alliance factor and three secondary factors, each corresponding to one of the components. This definition of alliance is gaining in acceptance, but because the precise definition of alliance has varied greatly, there is a need for further clarification of this therapeutic construct.

Horvath and Greenberg7 developed the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI), therapist and client versions. The WAI-T and WAI-C are designed to yield three alliance scales, corresponding to Bordin's6 components: Goal, Task, and Bond. These scales were shortened from 36 items to 12 items by Tracey and Kokotovic,8 and Tichenor and Hill3 adapted the WAI to be rated by observers (WAI-O) by adapting the pronouns from the client and therapist forms. We chose to use the WAI-O-S (shortened observer-rated version) because it was based closely on the Bordin6 definition and is a widely used and accepted alliance scale.5 The observer version of the WAI was utilized because our study's sample consisted of audiotaped sessions of CBT, and we chose the short version so that our participant-to-variable ratio (where each scale item is considered a variable) would allow for a clear and stable factor structure with no spurious results. The WAI-O-S has been growing in popularity, but no published factor analysis of the scale exists. Because the WAI scales are very widely used in alliance research,5 a better understanding of their factor structure is necessary, especially in CBT.

Tracey and Kokotovic8 examined the factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory by comparing two rival definitions of alliance, one that posits a general alliance construct and another that views the Goal, Task, and Bond constructs as correlated but unique in their content. Their confirmatory factor analysis, however, resulted in only adequate fits at best, and they did not look at alliance in CBT. Their conclusion was that the WAI-T-S and WAI-C-S appear to measure primarily a General Alliance factor and secondarily three specific aspects of the alliance (Goal, Task, and Bond). This implies one general therapy alliance factor, with three subfactors.

In a more recent exploratory factor analysis, Hatcher and Barends9 looked at three alliance scales in psychodynamic therapy. Again, this study did not look at alliance in CBT, but their results illustrate the diversity of views that our field has of the construct of the alliance. Their results suggest that the alliance, as measured by the WAI client and therapist forms, has two independent factors, with Goal and Task items grouping on one factor and Bond items grouping on the other. These results seem to run counter to Tracey and Kokotovic's8 findings of one general alliance factor with three subfactors in the WAI-C and WAI-T. Bordin's6 model, as measured by the WAI, seems to suggest several components, but researchers continue to assume a one-factor construct of alliance,9,10 even though this can lead to problems in research, especially if alliance is more complex than believed by many. Horvath11 states that “most [alliance] scales purport to measure a number of constituent elements (subscales) as well as the overall strength of the alliance.… All the scales tacitly assume that the components are of equal import and are additive. Thus, an alliance score that is the unweighted sum of all the scale scores is generated by each instrument” (p. 262). Perhaps the components of alliance need to be weighted differently, or maybe they should even be looked at as independent constructs.

Although the importance of alliance is generally accepted, and researchers, as we have seen, have sought a deeper understanding of the components of alliance in other forms of therapy, the therapeutic effect of alliance in CBT has remained controversial. A question remains as to the temporal sequence in formation of alliance—whether alliance causes outcome or outcome causes alliance. DeRubeis and Feeley12 have shown that alliance does not predict outcome in CBT and that the correlation may reflect the effect of outcome on alliance, but this study, as well as a replication of it,13 treated the alliance as one general factor. Raue and Goldfried14 report that the therapeutic relationship is seen as central within CBT, that “successful cognitive-behavioral interventions are unlikely to occur unless there exists a good working alliance—a good therapeutic bond, and a mutual agreement on goals and therapeutic methods” (p. 135). But they admit that only a small amount of research has been conducted on the alliance in CBT and that research on the unique nature of the alliance in CBT is needed.14 It is important that we understand the construct of alliance better because so few studies have looked at the theoretical dimensions of alliance in CBT. In particular, if alliance is truly an important construct of therapy, we need to better understand how to measure it—especially in CBT, where the therapeutic importance of alliance has been questioned.12,15

The present project thus aimed to determine the factor structure of alliance in CBT. We wished to examine whether Bordin's6 hypothesized structure accurately represents the factor structure of alliance in CBT by assessing that structure as measured by the WAI-O-S. We hypothesized that Bordin's6 model suggests related but independent components of alliance, rather than the one general alliance factor that many assume. In this way, we hoped to determine whether 1) a general alliance factor exists or 2) alliance in CBT consists instead of multiple independent factors. In the latter case, new scales would be required to accurately measure the construct of alliance.

METHODS

Sample

We looked at CBT that took place with 94 patients in the Jacobson et al.16 study. Patients' average age was 39 years, the female-to-male ratio was approximately 3.5 to 1, and more than 80% of patients were Caucasian. More detailed patient demographics can be found in Table 1 of Jacobson et al.16 Patients met criteria for major depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,17 scored at least 20 on the Beck Depression Inventory,18 and scored 14 or greater on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.19

Four experienced cognitive therapists provided treatment. Their average age was 44 years (range 37 to 49 years), and they averaged 15 years of postdegree clinical experience (range 7 to 20 years). They had been practicing CBT for an average of 10 years since their formal training, with a range of 8 to 12 years. All four therapists had participated in at least one previous clinical trial in which they served as research therapists for CBT treatment.

Patients were treated with standard cognitive-behavioral therapy in the second session (described in Jacobson et al.16). The study included all sessions of CBT, but we chose to look only at session 2 of CBT in order to minimize the effect of treatment outcome on our measurement of alliance.

Measures

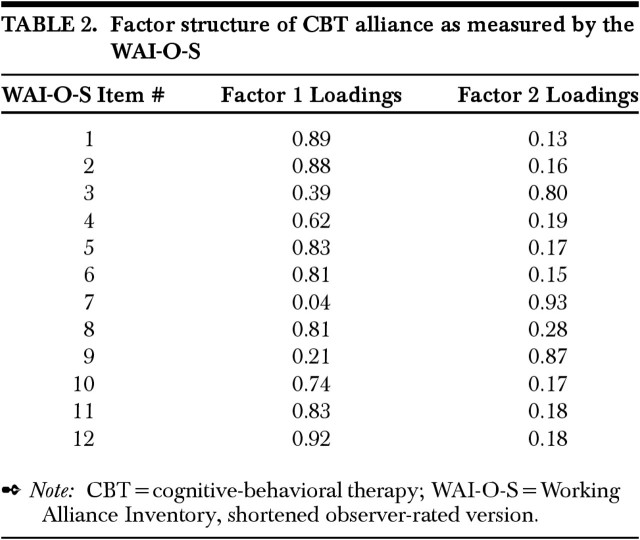

The WAI-O-S (short observer-rated version) was completed for each of the 70 tapes of session 2 by each of two raters as described below. This scale consists of 12 items, 10 positively worded and 2 negatively worded, rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale. The items are divided into three subscales of 4 items each, as shown in Table 1. The subscales, based on Bordin's6 working alliance theory, are Goal (agreement about goals of therapy; e.g., “The client and therapist have established a good understanding of the changes that would be good for the client”), Task (agreement about the tasks of the therapy; e.g., “There is agreement on what is important for the client to work on”), and Bond (the bond between the client and therapist; e.g., “There is mutual trust between the client and therapist”). The WAI-O-S has been previously shown to have a good reliability (r=0.81; L. Gelfand and R. DeRubeis, unpublished manuscript), and research has also shown strong support for the reliability of the WAI scales in general, as well as some support for their validity.20

TABLE 1. All items on WAI-O-S as organized by the three subfactors of the General Therapeutic Alliance Factor.

Procedure

All study sessions were audiotaped. We rated session 2 of CBT. This resulted in a total of 94 sessions. Fifteen of these sessions were removed from the study because either the patient dropped out of therapy before the 8th session or the patient's BDI score was 14 or less at session 1. Of the remaining 79 audiotaped sessions, 9 were inaudible, leaving us with 70 total observations of session 2. The two raters were a University of Pennsylvania psychology major who participated in approximately 25 hours of training and a University of Pennsylvania psychology graduate student with extensive rating experience. Training was completed by using sample sessions of CBT that the two raters rated separately, comparing the ratings afterwards. Training proceeded until the two raters had a similar understanding of the scale items and scoring procedures, and until the reliability between the two raters was deemed acceptable. Ratings were made independently after listening to an entire session of therapy and then averaged, and the raters were blind to the identity of the patient and therapist and to the eventual outcome of each case.

The interrater reliability of the two raters on the WAI-O-S, estimated by a Pearson correlation coefficient, was 0.67. The item-by-item interrater reliabilities ranged from a low of 0.14 to a high of 0.65, with a median of 0.42. We would have liked slightly higher item-by-item reliabilities, especially for item 4, which had a reliability of only 0.14, but overall, the interrater reliability and the item-by-item interrater reliabilities were typical for observer alliance scales.3

Data Analysis

We managed to secure a sample (N=70) that provided a participant-to-factor ratio (for the two factors described below) of 35:1 and a participant-to-variable ratio (for the 12 scale items) of 6:1. This should yield a clear and stable factor solution with no spurious findings. In order to determine the factor structure of the 12-item WAI-O-S rating scale, ratings were subjected to a principal components analysis using JMP-IN (SAS Institute, Inc.) statistical software. We determined the number of factors by using the “eigenvalue greater than 1” criterion. After the number of factors was determined, orthogonal rotation was performed.21,22

RESULTS

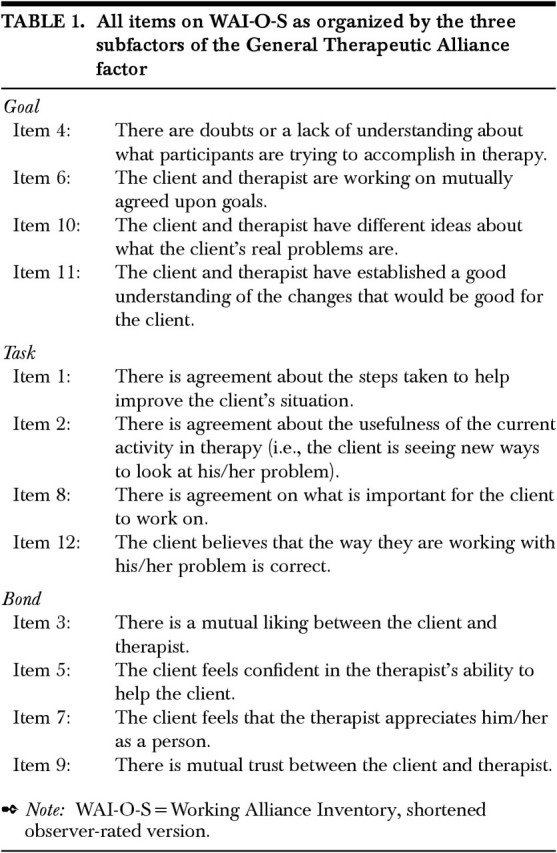

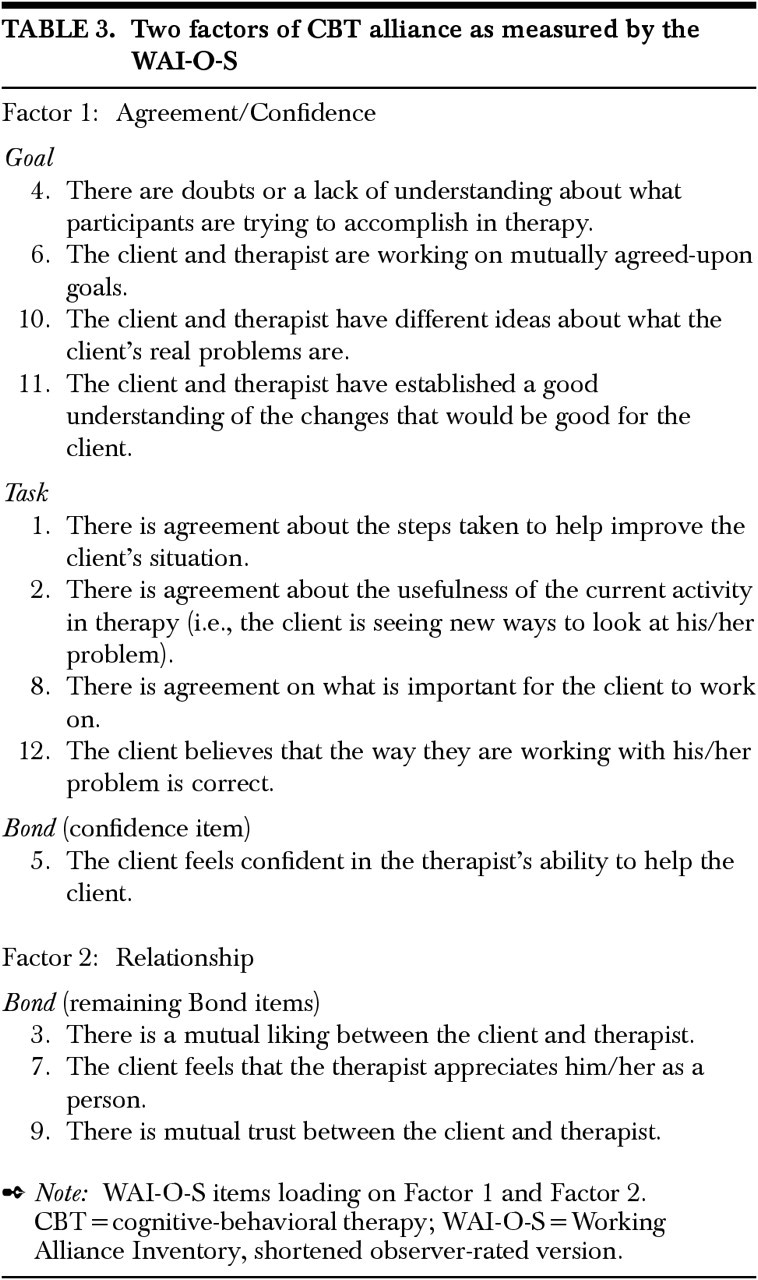

Our principal components analysis revealed that CBT alliance, as measured by the WAI-O-S, has a factor structure consisting of two independent factors. The principal component eigenvalues were 7 and 1.8, accounting for 73.4% of the total sample variance (58.4% and 15%, respectively). After orthogonal rotation, the two factors were readily interpretable (Table 2). The WAI-O-S Goal and Task items group on the first factor, along with the confidence Bond item (Item #5), and the other three Bond items group on factor 2 (Table 3).

TABLE 2. Factor structure of CBT alliance as measured by the WAI-O-S.

TABLE 3. Two factors of CBT as measured by the WAI-O-S.

Factor 1: Agreement/Confidence.

The first factor consists of the four Goal items, four Task items, and one Bond item from the WAI-O-S. As shown in Table 3, this factor includes items such as “There is agreement about the steps taken to help improve the client's situation,” and “The client and therapist are working on mutually agreed-upon goals.” The Bond item that loaded highly on this factor was item 5, “The client feels confident in the therapist's ability to help the client.” The item-by-item factor loadings can be seen in Table 2, clearly showing which items belong with which factor.

Factor 2: Relationship.

The second factor consists of the remaining three Bond items of the WAI-O-S. The items can be seen in Table 3 and include those items that are related to the interpersonal relationship between the therapist and the patient. The item-by-item factor loadings appear in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

These findings show us that Bordin's6 Goal and Task components seem to go together, at least in CBT. Factor analysis does not necessarily suggest that Goal and Task are not distinct concepts, but what it does show is that they covary in CBT and are largely independent of the other alliance factor, Relationship. Bordin's6 components may in fact be distinct concepts, but the important finding is that Task and Goal items, as well as the confidence Bond item, should be measured together, separately from the items that refer to the interpersonal relationship between therapist and client. If we are to make use of these findings, new scales will be needed that are based on the two factors discovered.

The results suggest a rethinking of Bordin's6 model of alliance in CBT. Alliance in CBT may in fact be made up of two independent constructs, the Agreement/Confidence factor and the Relationship factor. One important implication of this finding is that many past studies looking at alliance in CBT may have been mistaken in looking mainly at a general alliance factor rather than the two-factor structure we have discovered. Also, the WAI-O-S scale is growing in popularity, and the other WAI scales have been some of the most often used alliance scales for years.5 Because all of these scales are based on Bordin's6 model of alliance, it is important to acknowledge the possibility that the Task and Goal components, though distinct, covary as one factor, as measured in CBT by the WAI scales. Furthermore, the confidence item does not seem to fit in Bordin's6 Bond component, suggesting that confidence in the therapist and therapy also falls within the factor comprising Task and Goal.

In CBT, it seems reasonable that once a patient participates collaboratively in carrying out the therapy according to its rationale, he or she will have learned some of the goals of the therapy and the tasks that are conducted in order to achieve those goals. The goal of changing irrational thinking, for example, and the task of working on irrational thoughts seem explicitly related, possibly explaining why Task and Goal items may covary and result in a separate factor in CBT, independent from the Relationship factor. The confidence item from Bordin's6 Bond subscale may load on the Agreement factor because confidence in the therapist may speak to something different from the interpersonal relationship with the therapist. Confidence in a therapist's ability to help the client refers to helping the client with the tasks and also helping the client eventually achieve certain goals; it does not refer so much to the interpersonal relationship with the therapist. The Relationship factor speaks more to emotional elements such as mutual liking, trust, and appreciation between the therapist and client, and not so much to the more rational elements of the actual work done in CBT and the client's confidence in the therapist's ability to perform that work.

Although our findings suggest important and new directions in CBT alliance research, concentrating not on one general alliance factor but on two independent factors (Agreement/Confidence and Relationship), this study does have some limitations. First, the fact that we had only audiotapes, as opposed to video, may have made the observation of alliance more difficult. Second, we used a short version of the WAI-O. The long version would have had three times as many items to load onto factors. With only 12 items, we may have missed a more precise conceptualization of the construct of alliance in CBT. For example, we would have been happier with more than one confidence item, looking for those items to load onto the Agreement/Confidence factor rather than the Relationship factor.

Our study underscores the need for future research, suggesting the need for new alliance scales that take the two-factor conceptualization of alliance into account. That “alliance” is one general construct can no longer be an acceptable assumption in CBT research. Luborsky et al.23 also suggest that the factor structure of alliance in psychodynamic therapy may in fact consist of several independent factors. Future factor analyses should be conducted on all forms of therapy to better understand the alliance. Given the WAI scales' widespread use, their pantheoretical nature, and the evidence of their reliability and validity,20 researchers undertaking future factor analyses should use the longer versions of these scales and attempt to replicate our results. A closer look at other alliance scales would be of interest as well, since different measures may tap into different and distinct aspects of the alliance. There is a lot of work ahead for our field, but a deeper and more precise understanding of the therapeutic alliance is necessary to examine a construct that may in fact be far more complex than we have assumed.

References

- 1.Seligman MEP: What You Can Change and What You Can't. New York, Fawcett Columbine, 1993

- 2.Safran J, Muran JC: Negotiating the Therapeutic Alliance: A Relational Treatment Guide. New York, Guilford, 2000

- 3.Tichenor V, Hill CE: A comparison of six measures of working alliance. Psychotherapy 1989; 26:195–199 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horvath AO, Symonds BD: Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology 1991; 38:139–149 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK: Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:438–450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bordin ES: The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 1979; 16:252–260 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horvath AO, Greenberg LS: Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 1989; 36:223–233 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tracey TJ, Kokotovic AM: Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psycholology 1989; 1:207–210 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatcher RL, Barends AW: Patients' view of the alliance in psychotherapy: exploratory factor analysis of three alliance measures. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:1326–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvio AM, Beutler LE, Wood JM, et al: The strength of the therapeutic alliance in three treatments for depression. Psychotherapy Research 1992; 2:31–36 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horvath AO: Research on alliance, in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. New York, Wiley, 1994, pp 259–286

- 12.DeRubeis RJ, Feeley M: Determinants of change in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1990; 14:469–482 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feeley M, DeRubeis RJ, Gelfand LA: The temporal relation of adherence and alliance to symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67:578–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raue PJ, Goldfried MR: The therapeutic alliance in cognitive-behavior therapy, in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. New York, Wiley, 1994, pp 131–152

- 15.Barber JP, Luborsky L, Crits-Christoph P, et al: Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome in treatment of cocaine dependence. Psychotherapy Research 1999; 9:54–73 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, et al: A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987

- 18.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 1967; 6:276–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horvath AO: Empirical validation of Bordin's pantheoretical model of the alliance: the Working Alliance Inventory perspective, in The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. New York, Wiley, 1994, pp 109–128

- 21.Johnson RA, Wichern DW: Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1992

- 22.Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, et al: Multivariate Data Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1995

- 23.Luborsky L, Barber JP, Siqueland L, et al: The revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire-II (HAq-II): psychometric properties. J Psychother Pract Res 1996; 5:260–271 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]