Abstract

The tumor suppressor protein p53 is a short-lived transcription factor due to Mdm2-mediated proteosomal degradation. In response to genotoxic stress, p53 is stabilized via posttranslational modifications which prevent Mdm2 binding. p53 activation results in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. We previously reported that tight regulation of p53 activity is an absolute requirement for normal nephron differentiation (Hilliard S, Aboudehen K, Yao X, El-Dahr SS Dev Biol 353: 354–366, 2011). However, the mechanisms of p53 activation in the developing kidney are unknown. We show here that metanephric p53 is phosphorylated and acetylated on key serine and lysine residues, respectively, in a temporal profile which correlates with the maturational changes in total p53 levels and DNA-binding activity. Site-directed mutagenesis revealed a differential role for these posttranslational modifications in mediating p53 stability and transcriptional regulation of renal function genes (RFGs). Section immunofluorescence also revealed that p53 modifications confer the protein with specific spatiotemporal expression patterns. For example, phos-p53S392 is enriched in maturing proximal tubular epithelial cells, whereas acetyl-p53K373/K382/K386 are expressed in nephron progenitors. Functionally, p53 occupancy of RFG promoters is enhanced at the onset of tubular differentiation, and p53 loss or gain of function indicates that p53 is necessary but not sufficient for RFG expression. We conclude that posttranslational modifications are important determinants of p53 stability and physiological functions in the developing kidney. We speculate that the stress/hypoxia of the embryonic microenvironment may provide the stimulus for p53 activation in the developing kidney.

Keywords: posttranslational modifications, Mdm2, nephron differentiation

the tp53 gene encodes a transcription factor that maintains genomic integrity via its ability to induce cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis (4, 46). The p53 protein is composed of 393 amino acids in humans (390 amino acids in the mouse) and consists of several functional domains: N-terminus transactivation and proline-rich domains, a central core DNA-binding domain, and a C-terminus-regulatory domain (38). Hot spot mutations found in 50% of human cancer are for the most part located in the DNA-binding domain (12).

Regulation of cellular p53 expression is mainly controlled at the protein level via posttranslational modifications and by interactions with the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mdm2 (21, 28). Under normal conditions, cellular p53 levels and activity are kept low via Mdm2-mediated ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation. Mdm2 gene expression is positively regulated by p53, thus defining a negative feedback loop that controls p53 activity (23). Also, Mdm2 associates with chromatin-bound p53 at target promoters (24); in that capacity, Mdm2 recruits histone modifiers that remodel local chromatin structure as well as modify p53 itself.

p53 activity and stability are regulated through a multitude of posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, sumoylation, and ubiquitination (3, 6, 21, 38, 50). In response to stress, p53 is phosphorylated by a number of kinases on serine residues, mainly clustered within the N-terminal region (e.g., S6, S9, S15, and S20) (7). Phosphorylation of p53 prevents Mdm2 binding and leads to p53 stabilization and transactivation (34). In addition, several histone acetyltransferases are known to acetylate p53 at different lysine residues, including CBP/p300 (K370, K372, K373, K381, K382, K386); PCAF (K320); and Tip60/hMOF (K120, K164) (5, 6, 15, 18, 21). Acetylated p53 has a higher DNA-binding affinity, is protected from ubiquitination, and modulates transcription through recruitment of coactivators/repressors (5, 24, 26, 32). It has been proposed that different p53 acetylation cassettes serve as a code providing p53 with DNA-binding specificity and selective gene activation potential (26). Three different methyltransferases have been shown to methylate C-terminal lysine residues of p53. Set7/9-mediated monomethylation of K372 promotes p53 activity, whereas monomethylation at K370 and K382 by Smyd2 and Set8/PR-Set7, respectively, represses p53 activity (13, 21, 22, 48). Modification of p53 by the ubiquitin-like modifiers SUMO and Nedd8 further add to the competition for the C-terminal lysines. Sumoylation of p53 at K386 by Summo-1 and neddylation by Mdm2 at K370, K372, and K373 inhibit p53-mediated transcriptional activation (9, 11, 21). Although the nature and role of p53 posttranslational modifications in the p53 tumorigenic and genotoxic responses have been extensively investigated, much less attention has been paid to the nature and potential role of these modifications during normal development.

Although previous studies have shown that tight regulation of basal p53 levels/activity is essential for proper nephron differentiation (20, 42), the developmental mechanisms responsible for p53 activation and stability remain largely unknown. The present study was designed to determine whether embryonic p53 is posttranslationally modified and how these modifications might affect the developmental expression, transcriptional activity, and spatial localization of p53 in the developing kidney. We also examined the effect of loss and gain of function of p53 on nephron differentiation gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, tissues, and organ culture.

All animal protocols utilized were in strict adherence to guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tulane University. Wild-type CD1 mice were purchased from Charles Rivers Laboratories. TPp53−/− mice on a C57BL6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mdm2 deletion from the ureteric bud lineage was accomplished by crossing Mdm2LoxP/LoxP mice with Hoxb7-Cre mice (20). For the organ culture studies, embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) metanephroi were cultured on Transwell filters in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% FCS at 37°C/5% CO2, as described (20, 42).

Semiquantitative and quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from kidney samples using an RNAqueous-96 Automated Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). For semiquantitative RT-PCR, the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) was used. Generally, between 1 and 2 μg of RNA was used for RT and 1 or 2 μl of cDNA was used for PCR. Sequences of PCR primers are listed in Table 1. PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel prestained with ethidium bromide and analyzed using the Alpha Innotech FluorChem FC2 imaging system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in quadruplicate using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-time PCR system and TaqMan GenExpression Assays (Applied Biosystems) for aquaporin-2 (AQP2; Mm00437575_m1)l; Atp6v1v1 V1-H-ATPase β1 (Mm00460309_m1); carbonic anhydrase 2 (Ca2; Mm00501572_m1); bradykinin B2 receptor (Bdkrb2; Mm00437788_m1); and GAPDH (endogenous control, FAM/MGB probe, nonprimer limited; no. 4352932E). The setup of the reaction consisted of 1 μl of cDNA (100 ng), 1 μl of TaqMan primer set, 10 μl Taq (TaqMan Fast Universal PCR master mix, No AmpErase UNG; no. 4366072), and 8 μl of H2O under the following PCR conditions: step 1, 95°C for 20 s; step 2, 95°C for 3 s; and step 3, 60°C for 30 s; steps 2 and 3 were repeated 40 times.

Table 1.

List of primers used in semiquantitative RT-PCR

| Gene | Primer Sequence | Product Size, bp |

|---|---|---|

| p53 | Forward: 5′-ATAGGTCGGCGGTTCAT-3′ | 150 |

| Reverse: 5′-CCCGAGTATCTGGAAGACAG-3′ | ||

| AQP1 | Forward: 5′-CTCTTCGTCTTCATCAGCATT-3′ | 711 |

| Reverse: 5′-GTCGTCAGCATCCAGGTCATA-3′ | ||

| AQP2 | Forward: 5′-GCTCCTTTTCGTCTTCTTTGG-3′ | 622 |

| Reverse: 5′-GGTCGAGGGGAACAGCAGGTA-3′ | ||

| AQP4 | Forward: 5′-GTCCTCATCTCCCTTTGCTTT-3′ | 231 |

| Reverse: 5′-GACTCCCAATCCTCCAACCAC-3′ | ||

| Bdkr2 | Forward: 5′-AGAACATCTTTGTCCTCAGCG-3′ | 572 |

| Reverse: 5′-CGTCTGGACCTCCTTGAACT-3′ | ||

| CA2 | Forward: 5′-CTCTCAGGACAATGCAGTGC-3′ | 416 |

| Reverse: 5′-ATCCAGGTCACACATTCCAGC-3′ | ||

| αENac | Forward: 5′-AAAGCGTCTGCTCCGTGATGC-3′ | 556 |

| Reverse: 5′-CTAATGATGCTGGACCACACC-3′ | ||

| AT1a | Forward: 5′-GCATCATCTTTGTGGTGGG-3′ | 641 |

| Reverse: 5′-GAAGAAAAGCACAATCGCC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | Forward: 5′-AATGCATCCTGCACCACCAACTGC-3′ | 555 |

| Reverse: 5′-GGCGGCCATGTAGGCCATCTGGAG-3′ |

See the text for definitions.

Cell culture, DNA constructs, and reporter assays.

p53-null human lung carcinoma cells (H1299) were maintained in minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The rat BdkrB2(pBK2–94/+55-CAT), rat Agtr1a (pAT1a-1.2/LUC), mouse AQP2 (−10 kb/CAT), and pG13-LUC promoter reporter constructs have been described previously (35, 40). p53 mutant constructs (SA-15, TA-18, SA-20, 6KR) were generously provided by Dr. T.-P. Yao (Duke University). Additional mutant p53 constructs were generated in our laboratory using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cotransfection of reporter constructs along with wild-type (pCMV-p53, from G. Morris, Tulane University) or mutant p53 constructs was performed using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations as described (43). A control β-galactosidase-encoding vector, pSVZ (Promega), was cotransfected to correct for transfection efficiency. Additional controls included transfections with pCMV-CAT (pCAT3Basic) or pCMV-empty (pCDNA3.1) vectors. Aliquots of cell lysate were analyzed for CAT or LUC activity after normalization for protein content or β-galactosidase activity.

Western blot analysis.

Nuclear and cytosolic protein fractions were prepared using a Nuclear/Cytosol Fractionation Kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Immunoblotting was performed using 20–50 μg of protein samples. The following primary antibodies were used: total p53, FL-393X (sc-6243, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), acetyl-p53K373/K382 (06–758, Upstate Biotechnology), acetyl-p53K379 (2570S, Cell Signaling), phospho-p53S392 (9281S, Cell Signaling), phospho-p53S6 (9285, Cell Signaling), phospho-p53S9 (9288, Cell Signaling), phospho-p53S15 (9284S, Cell Signaling), and mouse anti-β-actin (610153, BD Transduction Laboratories).

EMSA.

EMSA was performed as previously described (40). Briefly, 32P-labeled duplex oligonucleotides (∼50,000 cpm) were incubated for 20 min at room temperature with 5 μg of nuclear extracts. Reactions containing an antibody against ac-p53K373/K382 (Upstate Biotechnology), or p-p53S392 (Cell Signaling), were preincubated with the nuclear extract on ice for 30 min before addition of the radiolabeled probe. The binding reaction was loaded onto a 6% acrylamide gel electrophoresed at 200 V for 2 h in 0.25× Tris borate EDTA (TBE) solution. Following electrophoresis, the acrylamide gel was soaked in a 10% glycerol solution for 10 min, dried for 1.5 h at 80°C using a gel dryer, and exposed overnight to capture autoradiography.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed using an EZ-ChIP kit (Upstate Biotechnology) with modifications (41). Kidney tissue was minced and cross-linked in PBS/1% formaldehyde solution for 15 min and quenched by addition of 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. Tissue was rinsed in 1× PBS, homogenized, and lysed in SDS-lysis buffer. DNA was sheared by sonication to produce an average DNA fragment size between 500 and 1,000 bp and diluted 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-p53 (FL-393X) antibody or control normal immunoglobulin (IgG) overnight at 4°C. Precipitated complexes were captured on protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen), washed and eluted from the beads, and cross-links were reversed at 65°C overnight. Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified and used for semiquantitative PCR. Sequences for the primers used for PCR were as follows (all mouse): Bdkrb2, forward 5′-TTGAAAGATGAGCTTGTTC-3′, and reverse 5′-AAACTCACCTTTTCTCAA; Atp6V0A2, forward 5′-GAGAGAAGAGAGAAGAGA and reverse 5′-CTGCTTTTAGAGTTTTGTT; Nkcc1, forward 5′-GTTAATCTGGGAGGAATG and reverse 5′-GCATCAATGTTATCTTCAA; ENaC-γ, forward 5′-CCAAAGAATAAATGATCTGT and reverse 5′-TCTCTTATCTCAGTTCCA; p21, forward 5′-CCTTTCTATCAGCCCCAGAGGATACC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GACCCCAAAATGACAAAGTGACAA-3′; DDX-17, forward 5′-gattaaaacttgagcatcc and reverse, 5′-AGATCTTTATCCGTTTGG; and BAD, forward 5′-CATTTTACAGGAGGGAAT and reverse 5′-CTGACCCAATCAGTTTTC.

Immunohistochemistry.

Kidneys were fixed in 10% formalin at 4°C overnight, processed for paraffin embedding, sectioning (5 μm), and immunostained as described (20). The primary antibodies used were acetyl-p53K373/K382, 1:100 dilution (06–758, Upstate Biotechnology); acetyl-p53K386, 1:100 dilution (ab52172, Abcam); phospho-p53S392, 1:100 (sc-56173, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); proliferating cell nuclear antigen [PCNA, 1:200 dilution (M0879, Dako Cytomation)]; phospho-histone H3 (Ser10), 1:300 dilution (9701, Cell Signaling); E-cadherin, 1:300 (610181, BD Transduction Laboratories); AQP2, 1:500 dilution (sc-9882, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); neural cell-associated marker [NCAM; 1:200 dilution (C9672, Sigma)]; FITC-conjugated Lotus tetragonolobus lectin agglutinin (LTA; 1:300 dilution, FL-1321, Vector Laboratories); and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), 1:500 dilution (D1306, Invitrogen). For immunofluorescence detection, we used donkey anti-mouse or donkey anti-rabbit secondary IgG antibodies with Alexa Fluor 555 or 488 conjugates (Invitrogen). The immunofluorescent images were captured using a 3-dimensional or deconvolution microscope (Leica DMRXA2).

Statistical analysis.

The results are presented as means ± SE. Comparisons between the groups were performed by an unpaired t-test or ANOVA using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.01). Differences were considered significant if the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

p53 protein is posttranslationally modified in a developmentally regulated manner.

We have previously demonstrated that kidney p53 mRNA levels decline by ∼50% from embryonic to adult life (20, 42). Here, we show that p53 protein expression is highly abundant in the embryonic kidney but declines dramatically postnatally to almost undetectable levels in the adult kidney (Fig. 1A). To determine whether p53 modifications known to regulate p53 stability in response to DNA damage also occur in the embryo, we analyzed the temporal changes in p53 phosphorylation and acetylation, schematically depicted in Fig. 1B. Western blot analysis of nuclear protein extracts showed that the ac-p53K373,K382/total p53 ratio is significantly higher in the embryonic than postnatal kidney (Fig. 1C). Adult kidneys express very low to undetectable levels of ac-p53K373,K382 (data not shown). Similarly, the relative levels of p-p53S6,S9,S15,S392/total p53 declined significantly during the transition from embryo to adult (Fig. 1D). Adult kidneys expressed very low levels of total or modified p53 (Fig. 1, A and D). The parallel developmental changes in total and modified p53 suggest a possible role for p53 phosphorylation/acetylation in mediating p53 protein stability during kidney maturation.

Fig. 1.

Developmental changes in total and modified p53 in mouse kidneys. A: Western blot analysis of total p53 in nuclear extracts from embryonic (E), postnatal (PN), and adult kidneys. B: schematic of p53 posttranslational modifications investigated in this study. C and D: Western blot analysis of acetyl p53 and phosphorylated p53 in nuclear kidney extracts. Specificity of antibodies was tested in PN day 1 (PN1) p53+/+ and p53−/− whole kidney extracts. Equal protein loading was monitored by Ponceau S staining (not shown) and an anti-β-actin antibody. Acetylated and phosphorylated p53 densitometric values were normalized to total p53 values shown in A and expressed relative to the values on embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5).

Developmental changes in p53 DNA-binding activity.

We performed EMSA on kidney nuclear extracts to determine the maturational changes in p53 DNA-binding activity. A 32P-labeled oligonucleotide duplex corresponding to the conserved high-affinity p53-binding site in the Bkdr2 promoter (43) was used as a probe. Figure 2A shows that multiple DNA-protein complexes form when the BK2-P1 probe is incubated with E17.5 nuclear kidney extracts. As expected, no binding is detected in control p53-deficient H1299 cell extracts. Addition of an ac-p53K373/K382 antibody to the reaction mixture supershifts the DNA-protein complex, while addition of an anti-p53-pS392 antibody inhibits complex formation (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, when we compared probe binding to protein extracts at different stages, we found a progressive decrease in binding from E13.5 to adulthood, especially postnatally (Fig. 2, B and C).

Fig. 2.

Developmental changes in kidney p53 DNA-binding activity. A: EMSA with a 32P-labeled probe corresponding to the consensus p53-binding site in the Bdkrb2 promoter incubated with nuclear extract (NE) from E17.5 or H1299 cell lysate in the presence or absence of antibodies to ac-p53K373/K382 and p-p53Ser392. B and C: EMSA showing DNA-binding activity of labeled probe to kidney extracts at E13.5, E17.5, and PN1. For competition assays, 10- to 50-fold excess cold p53 oligonucleotide duplex was used. Lane 1, free probe; lane 2, probe in the presence of NE from the indicated stage; lane 3, probe in the presence of NE and competitor; lane 4, probe in the presence of NE and the indicated antibodies.

Effects of posttranslational modifications on p53 protein stability.

We next examined the effects of phosphorylation and acetylation on p53 protein stability under normal cellular conditions. A series of p53 mutant constructs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 3A) and transiently transfected into p53-deficient H1299 cells, followed by p53 immunoblotting. Mutagenesis of p53S15/T18/S20, but not p53S392, dramatically reduces p53 protein stability (Fig. 3, B and D). Whereas mutations of individual C-terminal lysines p53K373/K382/K386 had no effect on p53 stability, combined elimination of the six acetylation sites (p536KR) enhanced p53 stability relative to the wild-type protein (Fig. 3, C and D). Together, these findings indicate that posttranslational modifications exert differential effects on p53 stability.

Fig. 3.

Posttranslational modifications are important for p53 protein stability. A: schematic of the p53 mutations tested in this study. B and C: Western blots of p53 protein in H1299 cells transfected with p53-mutant constructs (see text for details). Bottom: immunoblots for β-actin. D: densitometric analysis of p53 protein expression of mutant constructs relative to wild-type (WT) p53. Data in the graph represent means ± SE of at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. WT p53.

Effects of p53 modifications on activity of RFG promoters.

We previously demonstrated that p53 transactivates the promoters of BdkrB2, AQP2, and Na-K-ATPase-α and represses the Agtr1a promoter (40). Cotransfection experiments performed in H1299 cells revealed that relative to wild-type p53, mutant p53S/A15 displayed significantly reduced transcriptional effects on the AQP2, BdkrB2, and Agtr1a promoter reporter constructs even after correction for p53 protein levels determined by Western blotting and densitometric analysis (Fig. 4). However, p53S/A15 was equally capable of activating PG13-Luc, a synthetic reporter construct driven by 13 tandem copies of a p53 consensus sequence (Fig. 4). p53T/A18 and p53S/A20 mutant constructs displayed lower transcriptional activity of AQP2 but not BdkrB2 promoter constructs; however, both mutants exhibited lower repression of Agtr1a (Fig. 4). Compared with WT-p53, p53S/A392 and p53K/R382 constructs showed only modest activation of the PG13-Luc construct but not others (Fig. 4). Although p536KR is a more stable protein (Fig. 3, C and D), this did not translate into enhanced transcriptional activity (Fig. 4). We conclude that posttranslational modifications of p53 have differential effects on its transcriptional activity of RFG promoters.

Fig. 4.

Effects of p53 modifications on renal function gene (RFG) expression. WT and mutant p53 constructs were cotransfected along with promoter-reporter constructs of BdkrB2, AQP2, Agtr1a (AT1a), or PG13 into H1299 cells, and lysates were assayed for luciferase or CAT activity 24 h posttransfection (see text for details). The graphs show the change in reporter activity for the indicated constructs adjusted to WT p53, which was arbitrarily set to 1.00. Data in each graph represent means ± SE of at least 3 experiments (*P < 0.05).

Spatial expression of ac-p53K386 and ac-p53K373/K382.

In the developing kidney, two distinct zones can be distinguished histologically: an outer cortical nephrogenic zone (NZ) and a subcortical differentiating zone (DZ). The NZ houses renal progenitors and nascent nephrons which express PCNA and NCAM, whereas the DZ contains maturing tubular structures which express differentiation markers. We sought to determine whether p53 modifications are associated with specific spatial expression patterns. Acetylation of p53 at K373/382/386 by CBP/P300 correlates with enhanced transcriptional activity and DNA-binding affinity (5). Immunofluorescence using antibodies specific to ac-p53K373/K382 or ac-p53K386 showed that ac-p53K373,K382,K386 are predominantly expressed in the NZ in an overlapping manner with PCNA and NCAM (Figs. 5, A–E, and 6, A and B). However, there seems to be more colocalization of ac-p53K386 with PCNA than there is between ac-p53K373/K382 and PCNA (Fig. 5, A–D). Moreover, ac-p53K373/K382/K386 are expressed within epithelial, E-cadherin-positive, tubules (Figs. 5F and 6E). Costaining with AQP2, a marker of collecting ducts, or LTA, a marker of proximal tubules, revealed that ac-p53K373/K382/K386 are mostly (but not exclusively) expressed in the collecting duct/distal nephron segments (Figs. 5, G and H, and 6, C, D, and F).

Fig. 5.

Spatial expression of ac-p53K373/382 in the developing kidney. Immunofluorescence staining is shown in kidney sections using antibodies to ac-p53K373/K382, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), neural cell-associated marker (NCAM), Lotus tetragonolobus lectin agglutinin (LTA), E-cadherin, aquaporin-2 (AQP2), and phospho-histone H3 (PH3). A–D: ac-p53K373/K382 is expressed in the nephrogenic zone (NZ) in embryonic and PN1 kidneys. E: ac-p53K373/K382 is enriched in NCAM-positive cap mesenchyme (CM). F: ac-p53K373/K382 is expressed in E-cadherin-positive epithelial tubules. G and H: ac-p53K373/K382 is expressed in maturing collecting ducts (CD) but not in proximal tubules (PT).

Fig. 6.

Spatial expression of ac-p53K386 in the developing kidney. Immunofluorescence staining is shown in kidney sections on E15.5 (A and B) or E17.5 (C and D) using antibodies to ac-p53K386, PCNA, E-cadherin, or AQP2. ac-P53K386 is expressed in proliferating cells of the NZ (A and B), ureteric bud branches (C), and collecting duct (D).

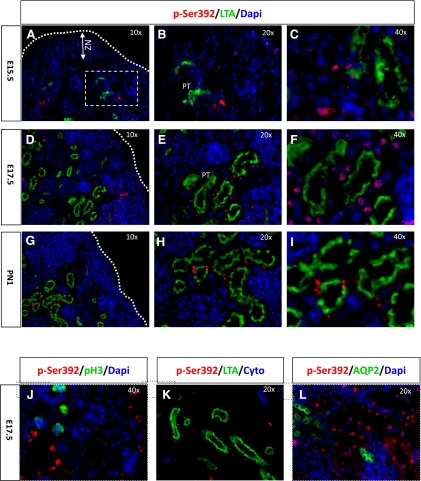

p-p53ser392is enriched in proximal tubules.

At E15.5, most tubular structures have not differentiated yet into mature proximal tubules, as indicated by the paucity of LTA staining compared with older age groups (Fig. 7A). At this stage, occasional p-p53S392-expressing cells are localized in newly formed tubular structures expressing LTA (Fig. 7, A–C). At E17.5 and posnatal day 1, when the cortex has demarcated into NZ and DZ, p-p53S392 expression is clearly enriched within LTA-positive proximal tubules (Fig. 7, D–I). Also, p-p53S392 displayed minimal if any colocalization in proliferating cells (Fig. 7, J and K) or AQP2+ collecting ducts (Fig. 7L). Collectively, these results demonstrate a stage- and cell type-specific expression of p-p53S392 in maturing proximal nephron segments.

Fig. 7.

Spatial expression of p-p53Ser392 in the developing kidney. Immunofluorescence staining is shown of kidney sections using antibodies to ac-p53Ser392, LTA, PH3, PCNA, or AQP2. A–I: the NZ is devoid of ac-p53Ser392 but is enriched in differentiated proximal tubules (PT). ac-p53Ser392 is not expressed in dividing cells (J and K) or collecting ducts (L).

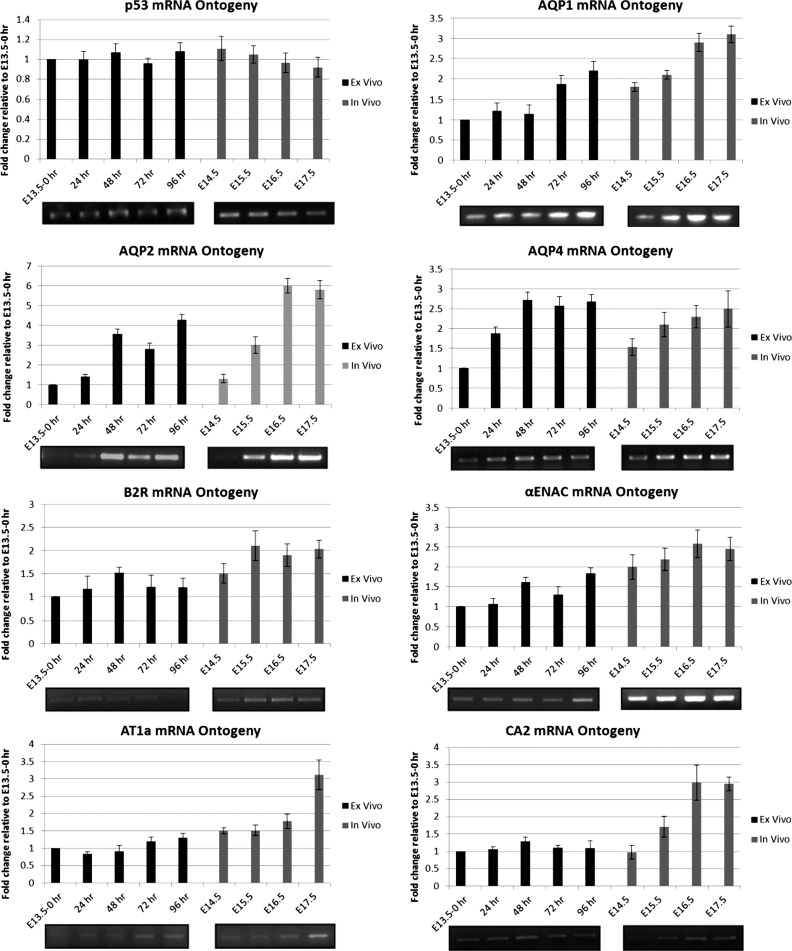

Ontogeny of p53 and RFGs.

We next examined the ontogeny of a subset of nephron differentiation genes, i.e., RFGs, in relation to the temporal expression of p53. RFG mRNA levels were quantified by RT-PCR using freshly harvested kidneys (in vivo samples, E13.5–E17.5) and compared with kidneys harvested and cultured (ex vivo samples, E13.5+96 h). p53 mRNA levels were maintained in the developing kidney from E13.5 to E17.5 (Fig. 8). On the other hand, most RFGs were significantly upregulated between E13.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 8). This discrepant expression pattern suggests that RFG expression is not primarily driven by ambient p53 levels. Furthermore, we found that the RFG expression pattern from in vivo samples was similar in ex vivo samples (Fig. 8), suggesting that blood flow and glomerular filtration are not required for the inductive expression of RFGs.

Fig. 8.

Developmental expression of RFGs in in vivo and ex vivo organ culture. RFG transcript levels in RNA samples from embryonic (E13.5, E14.5, E15.5, E16.5, E17.5) and organ cultured kidneys (E13.5+24, 48, 72, or 96 h) were determined by RT-PCR. Gene expression levels were normalized to GAPDH. The expression level at E13.5 was arbitrarily set to 1.0. Data in each graph represent means ± SE of at least 3 experiments. A representative ethidium bromide-stained gel is shown for each gene.

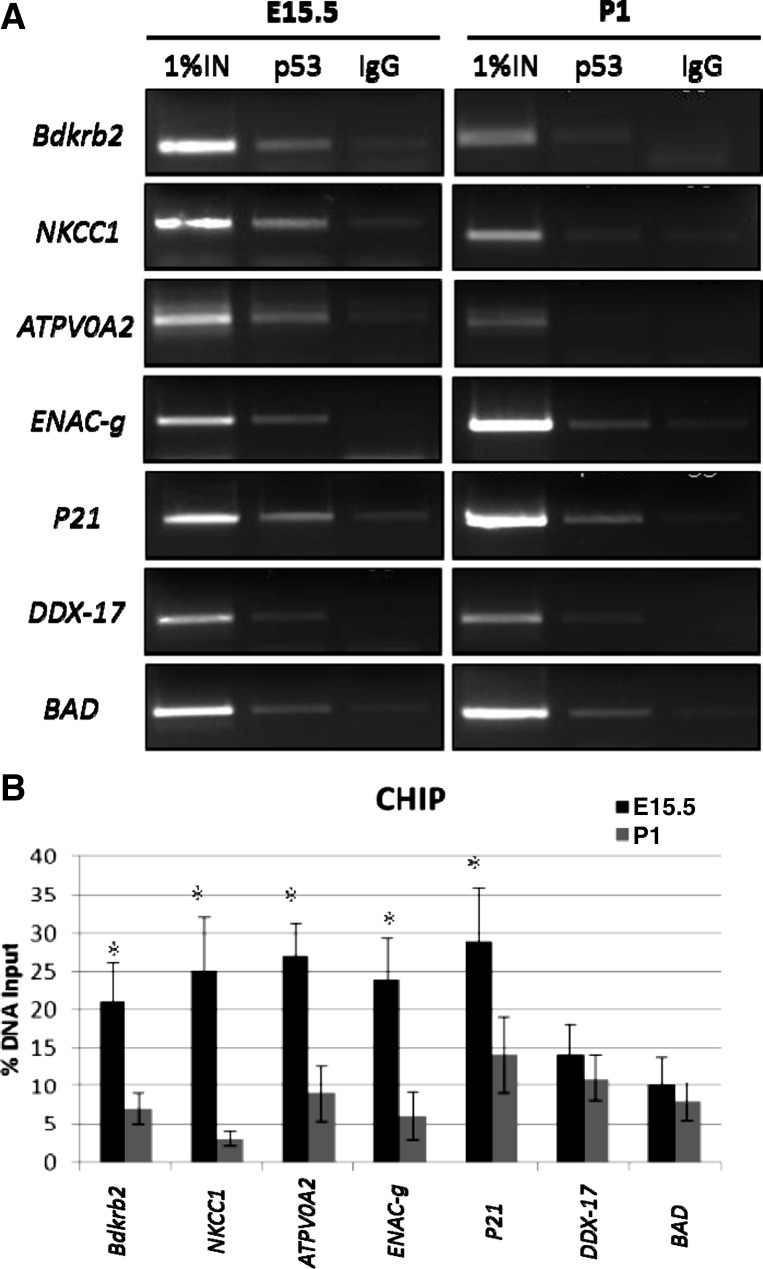

Developmental changes in p53 binding to RFG targets.

Since tissue levels may not reflect the actual functional importance of a transcription factor, we performed ChIP-PCR assays to examine p53 occupancy on RFG promoters in developing kidneys; as a control, we included known p53 targets such as p21, DDX-17, and BAD. The results demonstrate that p53 binding to RFGs peaks at the onset of tubular differentiation on E15.5 (Fig. 9, A and B). Although p53 was also bound to non-RFGs (DDX and BAD), a developmental pattern was not observed (Fig. 9, A and B). These data suggest that the onset of nephron differentiation is accompanied by enhanced p53 binding to RFG promoters.

Fig. 9.

Occupancy of RFG promoters by p53 during nephron differentiation. A: representative gel images of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments performed in embryonic (E15.5) and postnatal (PN1) kidneys using p53 (FL-393) antibody or control IgG. The precipitated chromatin was analyzed for p53 binding using primers for differentiation RFGs (Bdkrb2, NKCC1, ATPV0A2, ENAC-g, p21) and other p53 target genes (DDX-17, BAD). B: quantitative analysis of percentage of promoter-bound p53 for different target genes. Data are expressed in percent change relative to the amount of input DNA. Data in each graph represent means ± SD of at least 3 experiments (*P < 0.05).

Effect of altered p53 activity on RFG expression.

To assess the biological effects of altered p53 activity on the expression of RFGs in vivo, we performed quantitative RT-PCR on RNA extracted from embryonic p53+/+ and p53−/− kidneys and from mice with conditional ureteric bud-specific deletion of Mdm2 (UBMdm2−/−). The latter mice lack Mdm2 from the collecting duct system. We also performed ex vivo studies in E13.5 embryonic kidneys cultured in the presence of pifithrin-α (PFT-α), a small-molecule p53 inhibitor, or nutlin-3, a chemical compound which inhibits Mdm2-p53 interactions and thus stabilizes p53. Figure 10 shows that genetic or chemical inactivation of p53 downregulates Bdkr2, whereas CA2 (a marker of intercalated cells) was downregulated by PFT-α. Other markers, such as H+-ATPase and AQP2, were not affected. AQP2 is known to be regulated by the p53 family member p73 (39); therefore, compensation by other p53 family members might explain the modest effects of p53 inhibition.

Fig. 10.

Effect of altered p53 activity on RFG expression. p53−/− and UBMdm2−/− and WT littermate kidneys were harvested at E17.5, and extracted RNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR. For organ culture studies, metanephroi were dissected at E13.5 and incubated in the presence of pifithrin (PFT)-α (10 μM) or nutlin-3 (10 μM) for 96 h. Gene expression in PFT-α- or nutlin-treated kidneys was compared with control DMSO-treated kidneys, while expression in p53−/− and Ubmdm2−/− kidneys was compared with WT littermates. Data are expressed as relative fold-change from control/WT normalized at 1.0 (*P < 0.05).

Excessive p53 activity in vivo (UBmdm2−/−) and ex vivo (nutlin) upregulates Bdkr2, CA2, and H+-ATPase (Fig. 10). Total kidney AQP2 mRNA levels are upregulated in response to nutlin, but not in UBmdm2−/− mice; however, in situ hybridization did show upregulation of AQP2 mRNA in collecting ducts of UBmdm2−/− mouse (data not shown). These data are consistent with our overall hypothesis that p53 modulates RFG expression in vivo.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the mechanisms of p53 regulation during murine kidney development. The findings indicate that embryonic kidney p53 is phosphorylated and acetylated, and its endogenous activity is regulated by Mdm2. These two factors may contribute to its stability, cell type-specific expression, and target gene activation during nephrogenesis. We also report that p53-chromatin interactions on RFG target promoters are developmentally regulated.

We have previously reported that p53 is enriched in renal epithelial cells during nephron differentiation (16, 40, 42). We also identified several RFGs (Bdkrb2, AQP2, Na-K-ATPase-α1, and Agtr1) as a novel group of p53 target genes (35, 40, 41, 43, 44). Here, we report that the p53 protein is subject to developmental regulation, whereby expression is highest during nephrogenesis and is downregulated in the mature kidney. Importantly, we found that the p53 modification cassette during normal kidney development resembles the one elicited during the p53 response to DNA damage (10, 19, 21, 29, 37). This finding implies that the hyperproliferative state of embryogenesis may provide a stress signal leading to p53 activation (33, 45). The nature of the stress signal is unclear; we speculate that it may be related to a greater need for DNA repair during active DNA replication, cellular hypoxia, increased metabolic needs, and competition of rapidly dividing cells for nutrients, or handling of accumulating reactive oxygen species.

The results of the present study revealed that p53 phosphorylation on various serine residues is differentially acquired during nephron differentiation. Thus, whereas p53 N-terminal phosphorylation levels on Ser6, 9, and 15 are abundant during embryonic life, phosphorylation of p53 on Ser392 is relatively low in the embryonic kidney, but is induced postnatally. The physiological relevance of p53 phosphorylation in the developing kidney is unknown. This study offers some clues. Phosphorylation is required for p53 protein stabilization in response to DNA damage. Indeed, our in vitro data support the notion that phosphorylation of Ser15, 20, and Thr18 is required for full stabilization of p53. We therefore surmise that p53 N-terminal phosphorylation plays a role in p53 stability perhaps by limiting its interaction with Mdm2.

Ser392 (mouse Ser389) is one of the target residues phosphorylated in p53. Kinases that target this site in vitro are casein kinase II, the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR), and p38 MAP kinase (25). Although homozygous mutant p53S389A mice (serine 392 in human) are viable, p53S389A mutant cells are compromised in transcriptional activation of p53 target genes and apoptosis after UV irradiation (8). Moreover, p53S389A mice show increased sensitivity to UV-induced skin tumor development (8). Thus serine 392 (389) phosphorylation is required for the tumor-suppressive function of p53. The surge in p-p53Ser392 during later stages of kidney development suggests that this modification may be involved in programming of terminal differentiation gene expression. Furthermore, p-p53Ser392 is nephron segment specific (proximal tubule) and thus may be important in cell fate maintenance. Future studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

Unlike Ser392 phosphorylation, acetylation of p53 on Lys373, 382, and 386 is more active at embryonic stages than after birth. Physiologically, p53K373/K82 acetylation correlates with enhanced DNA-binding affinity and transcriptional activity (5), implying that p53 is transcriptionally more active in the embryonic than postnatal kidney. However, knockin mouse studies in which C-terminal lysines were mutated did not reveal a specific phenotype (27). We speculate that the distinct p53 posttranslational cassettes in the embryo may empower p53 with selective access to different target genes or recruitment of different cofactors, although their in vivo relevance may not become apparent under unstressed conditions.

Differential spatial expression patterns of p53 posttranslational modifications have not previously been associated with tissue differentiation. Given the roles of p53 in patterning of the intermediate mesoderm and development of the kidneys, liver, and neural tube (1, 2, 17, 30, 31, 47, 49), it would be important to determine whether key morphogenetic pathways (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, transforming growth factor-β, Wnt) target differential modifications on the p53 protein to affect developmental fate switches (14). It has been suggested that posttranslational modifications provide p53 with target gene specificity. For example, phosphorylation of p53 Ser46 and acetylation of Lys120 are proposed to influence the induction of specific apoptotic target genes, whereas acetylation of p53 Lys320 favors DNA binding to the p21 gene, promoting cell cycle arrest (36). Our promoter-reporter assays indicate that interference with N-terminal phosphorylation, but not acetylation, impacts p53-mediated activation of select RFGs. Although these results may not completely represent the in vivo conditions, they do confirm that p53 modifications confer transcriptional specificity.

We examined this using ChIP p53 binding to RFGs and other known targets during kidney development. p53 occupancy of RFG promoters is highly enriched at the onset of tubular differentiation at E15.5 compared with the postnatal kidney. Maintenance of RFG expression (with the exception of Bdkrb2) in p53-null mice may be related to compensation by other p53 family members (39). In addition, p53 did not display a similar developmental binding to the DEAD Box gene DDX17 or the proapoptosis gene BAD. It is tempting to speculate that in response to a differentiation signal, combinatorial patterns of p53 modifications allow one to distinguish between different biological responses via chromatin association and RFG transactivation.

The ubiquitin ligase Mdm2 mediates p53 proteosomal degradation (34). Moreover, the Mdm2 gene is positively regulated by p53, thus establishing a negative feedback loop which controls p53 levels physiologically. To examine how Mdm2-p53 interactions modulate RFG expression during nephron differentiation, we employed two complementary approaches: treatment of embryonic kidney cultures with chemical inhibitors of Mdm2 or p53 and targeted disruption of the Mdm2 or p53 genes. When analyzing the effect of altered p53 activity, we found changes in a subset of RFGs (AQP2, Bdkrb2, CA2) that are mainly expressed in ureteric bud derivatives; this is not surprising given that p53 is enriched within these structures (20, 42). Collectively, our data suggest that changes in RFG expression in vivo are more pronounced following p53 stabilization than p53 inactivation. We speculate that this may be due to redundancy by the p53 family members p63 and p73.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that the p53 protein in the embryonic kidney is subject to posttranslational modifications. These modifications impart p53 with nephron segment-specific expression patterns and are able to regulate p53 stability and target gene activation. The onset of nephron differentiation is accompanied by enhanced occupancy of p53 on promoters of RFGs. Future studies should elucidate the upstream kinases and signaling pathways which mediate these developmental changes in the Mdm2-p53 module and whether p53 modifications act as a fate switch during tissue patterning and organogenesis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant RO1DK62550 (S. El-Dahr). Z. Saifudeen is supported by Center of Biomedical Research Excellence Grant 1P20 RR017659.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.A. and S.H. performed experiments; K.A., Z.S., and S.S.E.-D. analyzed data; K.A., Z.S., and S.S.E.-D. interpreted results of experiments; K.A. prepared figures; K.A. drafted manuscript; K.A., S.H., Z.S., and S.S.E.-D. edited and revised manuscript; K.A., S.H., Z.S., and S.S.E.-D. approved final version of manuscript; S.S.E.-D. provided conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the El-Dahr and Saifudeen laboratories for insightful discussions and technical assistance. These studies were performed as part of a pre-doctoral dissertation thesis (K. Aboudehen).

REFERENCES

- 1. Amariglio F, Tchang F, Prioleau MN, Soussi T, Cibert C, Mechali M. A functional analysis of p53 during early development of Xenopus laevis. Oncogene 15: 2191– 2199, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armstrong JF, Kaufman MH, Harrison DJ, Clarke AR. High-frequency developmental abnormalities in p53-deficient mice. Curr Biol 5: 931– 936, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ashcroft M, Kubbutat MH, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 function and stability by phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 19: 1751– 1758, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Attardi LD, DePinho RA. Conquering the complexity of p53. Nat Genet 36: 7– 8, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barlev NA, Liu L, Chehab NH, Mansfield K, Harris KG, Halazonetis TD, Berger SL. Acetylation of p53 activates transcription through recruitment of coactivators/histone acetyltransferases. Mol Cell 8: 1243– 1254, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bode AM, Dong Z. Post-translational modification of p53 in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 793– 805, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown JM, Attardi LD. The role of apoptosis in cancer development and treatment response. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 231– 237, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bruins W, Zwart E, Attardi LD, Iwakuma T, Hoogervorst EM, Beems RB, Miranda B, van Oostrom CT, van den Berg J, van den Aardweg GJ, Lozano G, van Steeg H, Jacks T, de Vries A. Increased sensitivity to UV radiation in mice with a p53 point mutation at Ser389. Mol Cell Biol 24: 8884– 8894, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buschmann T, Fuchs SY, Lee CG, Pan ZQ, Ronai Z. SUMO-1 modification of Mdm2 prevents its self-ubiquitination and increases Mdm2 ability to ubiquitinate p53. Cell 101: 753– 762, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carter S, Vousden KH. Modifications of p53: competing for the lysines. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19: 18– 24, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiu SY, Asai N, Costantini F, Hsu W. SUMO-specific protease 2 is essential for modulating p53-Mdm2 in development of trophoblast stem cell niches and lineages. PLoS Biol 6: e310, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science 265: 346– 355, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chuikov S, Kurash JK, Wilson JR, Xiao B, Justin N, Ivanov GS, McKinney K, Tempst P, Prives C, Gamblin SJ, Barlev NA, Reinberg D. Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature 432: 353– 360, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Maretto S, Insinga A, Imbriano C, Piccolo S. Links between tumor suppressors: p53 is required for TGF-beta gene responses by cooperating with Smads. Cell 113: 301– 314, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dornan D, Shimizu H, Perkins ND, Hupp TR. DNA-dependent acetylation of p53 by the transcription coactivator p300. J Biol Chem 278: 13431– 13441, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El-Dahr SS, Aboudehen K, Saifudeen Z. Transcriptional control of terminal nephron differentiation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1273– F1278, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frenkel J, Sherman D, Fein A, Schwartz D, Almog N, Kapon A, Goldfinger N, Rotter V. Accentuated apoptosis in normally developing p53 knockout mouse embryos following genotoxic stress. Oncogene 18: 2901– 2907, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grossman SR. p300/CBP/p53 interaction and regulation of the p53 response. Eur J Biochem 268: 2773– 2778, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris SL, Levine AJ. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene 24: 2899– 2908, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hilliard S, Aboudehen K, Yao X, El-Dahr SS. Tight regulation of p53 activity by Mdm2 is required for ureteric bud growth and branching. Dev Biol 353: 354– 366, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hollstein M, Hainaut P. Massively regulated genes: the example of TP53. J Pathol 220: 164– 173, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang J, Dorsey J, Chuikov S, Perez-Burgos L, Zhang X, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D, Berger SL. G9a and Glp methylate lysine 373 in the tumor suppressor p53. J Biol Chem 285: 9636– 9641, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Juven T, Barak Y, Zauberman A, George DL, Oren M. Wild type p53 can mediate sequence-specific transactivation of an internal promoter within the mdm2 gene. Oncogene 8: 3411– 3416, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaeser MD, Iggo RD. Promoter-specific p53-dependent histone acetylation following DNA damage. Oncogene 23: 4007– 4013, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keller D, Zeng X, Li X, Kapoor M, Iordanov MS, Taya Y, Lozano G, Magun B, Lu H. The p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 alleviates ultraviolet-induced phosphorylation at serine 389 but not serine 15 and activation of p53. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 261: 464– 471, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knights CD, Catania J, Giovanni SD, Muratoglu S, Perez R, Swartzbeck A, Quong AA, Zhang X, Beerman T, Pestell RG, Avantaggiati ML. Distinct p53 acetylation cassettes differentially influence gene-expression patterns and cell fate. J Cell Biol 173: 533– 544, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krummel KA, Lee CJ, Toledo F, Wahl GM. The C-terminal lysines fine-tune P53 stress responses in a mouse model but are not required for stability control or transactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 10188– 10193, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell 137: 609– 622, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lakin ND, Jackson SP. Regulation of p53 in response to DNA damage. Oncogene 18: 7644– 7655, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lengner CJ, Steinman HA, Gagnon J, Smith TW, Henderson JE, Kream BE, Stein GS, Lian JB, Jones SN. Osteoblast differentiation and skeletal development are regulated by Mdm2-p53 signaling. J Cell Biol 172: 909– 921, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leveillard T, Gorry P, Niederreither K, Wasylyk B. MDM2 expression during mouse embryogenesis and the requirement of p53. Mech Dev 74: 189– 193, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li M, Luo J, Brooks CL, Gu W. Acetylation of p53 inhibits its ubiquitination by Mdm2. J Biol Chem 277: 50607– 50611, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Louis JM, McFarland VW, May P, Mora PT. The phosphoprotein p53 is down-regulated post-transcriptionally during embryogenesis in vertebrates. Biochim Biophys Acta 950: 395– 402, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manfredi JJ. The Mdm2-p53 relationship evolves: Mdm2 swings both ways as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor. Genes Dev 24: 1580– 1589, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marks J, Saifudeen Z, Dipp S, El-Dahr SS. Two functionally divergent p53-responsive elements in the rat bradykinin B2 receptor promoter. J Biol Chem 278: 34158– 34166, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mayo LD, Seo YR, Jackson MW, Smith ML, Rivera Guzman J, Korgaonkar CK, Donner DB. Phosphorylation of human p53 at serine 46 determines promoter selection and whether apoptosis is attenuated or amplified. J Biol Chem 280: 25953– 25959, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Minamoto T, Buschmann T, Habelhah H, Matusevich E, Tahara H, Boerresen-Dale AL, Harris C, Sidransky D, Ronai Z. Distinct pattern of p53 phosphorylation in human tumors. Oncogene 20: 3341– 3347, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oren M, Damalas A, Gottlieb T, Michael D, Taplick J, Leal JF, Maya R, Moas M, Seger R, Taya Y, Ben-Ze'ev A. Regulation of p53: intricate loops and delicate balances. Biochem Pharmacol 64: 865– 871, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saifudeen Z, Diavolitsis V, Stefkova J, Dipp S, Fan H, El-Dahr SS. Spatiotemporal switch from DeltaNp73 to TAp73 isoforms during nephrogenesis: impact on differentiation gene expression. J Biol Chem 280: 23094– 23102, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saifudeen Z, Dipp S, El-Dahr SS. A role for p53 in terminal epithelial cell differentiation. J Clin Invest 109: 1021– 1030, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saifudeen Z, Dipp S, Fan H, El-Dahr SS. Combinatorial control of the bradykinin B2 receptor promoter by p53, CREB, KLF-4, and CBP: implications for terminal nephron differentiation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F899– F909, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saifudeen Z, Dipp S, Stefkova J, Yao X, Lookabaugh S, El-Dahr SS. p53 regulates metanephric development. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2328– 2337, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saifudeen Z, Du H, Dipp S, El-Dahr SS. The bradykinin type 2 receptor is a target for p53-mediated transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem 275: 15557– 15562, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Saifudeen Z, Marks J, Du H, El-Dahr SS. Spatial repression of PCNA by p53 during kidney development. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F727– F733, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schmid P, Lorenz A, Hameister H, Montenarh M. Expression of p53 during mouse embryogenesis. Development 113: 857– 865, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sherr CJ, Weber JD. The ARF/p53 pathway. Curr Opin Genet Dev 10: 94– 99, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takebayashi-Suzuki K, Funami J, Tokumori D, Saito A, Watabe T, Miyazono K, Kanda A, Suzuki A. Interplay between the tumor suppressor p53 and TGF beta signaling shapes embryonic body axes in Xenopus. Development 130: 3929– 3939, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsai WW, Nguyen TT, Shi Y, Barton MC. p53-targeted LSD1 functions in repression of chromatin structure and transcription in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 28: 5139– 5146, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wilkinson DS, Ogden SK, Stratton SA, Piechan JL, Nguyen TT, Smulian GA, Barton MC. A direct intersection between p53 and transforming growth factor beta pathways targets chromatin modification and transcription repression of the alpha-fetoprotein gene. Mol Cell Biol 25: 1200– 1212, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zuckerman V, Wolyniec K, Sionov RV, Haupt S, Haupt Y. Tumour suppression by p53: the importance of apoptosis and cellular senescence. J Pathol 219: 3– 15, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]