Abstract

Elevated soluble fibrin (sFn) levels are characteristic of melanoma hematogeneous dissemination, where tumor cells interact intimately with host cells. Melanoma adhesion to the blood vessel wall is promoted by immune cell arrests and tumor-derived thrombin, a serine protease that converts soluble fibrinogen (sFg) into sFn. However, the molecular requirement for sFn-mediated melanoma-polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and melanoma-endothelial interactions under physiological flow conditions remain elusive. To understand this process, we studied the relative binding capacities of sFg and sFn receptors e.g., αvβ3 integrin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expressed on melanoma cells, ICAM-1 on endothelial cells (EC), and CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1) on PMNs. Using a parallel-plate flow chamber, highly metastatic melanoma cells (1205Lu and A375M) and human PMNs were perfused over an EC monolayer expressing ICAM-1 in the presence of sFg or sFn. It was found that both the frequency and lifetime of direct melanoma adhesion or PMN-facilitated melanoma adhesion to the EC in a shear flow were increased by the presence of sFn in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, sFn fragment D and plasmin-treated sFn failed to increase melanoma adhesion, implying that sFn-bridged cell adhesion requires dimer-mediated receptor-receptor cross-linking. Finally, analysis of the respective kinetics of sFn binding to Mac-1, ICAM-1, and αvβ3 by single bond cell tethering assays suggested that ICAM-1 and αvβ3 are responsible for initial capture and firm adhesion of melanoma cells. These results provide evidence that sFn enhances melanoma adhesion directly to ICAM-1 on the EC, while prolonged shear-resistant melanoma adhesion requires interactions with PMNs.

Keywords: shear rate, PMN, EC, fibrin, ICAM-1, αvβ3

melanoma metastasis consists of highly regulated molecular events, including tumor detachment from the primary lesion, translocation within the blood circulation, and successful adhesion to and extravasation from the walls of capillary vessels in target tissues (13). During their translocation to the lung capillaries, melanoma cells are subject to mechanical shear forces and interact with plasma proteins and immune cells that might regulate tumor cell (TC) adhesion and survival (31). Therefore, elucidating the interplay between these blood components and melanoma cells within the intravascular tumor microenvironment is critical for understanding the mechanism of metastasis.

Correlation between tumor metastasis and activation of blood coagulation has been described (65, 77). Specifically, several studies indicated that soluble fibrinogen (sFg) and fibrin (sFn) act as a rate-limiting step in primary capture of circulating melanoma cells (7, 12, 19, 28, 54). The procoagulant potential ascribed to melanoma cells has been linked to a transmembrane protein tissue factor (TF). Metastatic melanoma cells were reported to express 1,000-fold higher levels of TF on their membranes than nonmetastatic cells (44). The membrane-bound TF triggers coagulation by facilitating thrombin generation (66). Thrombin is a serine protease responsible for many homeostatic functions, including conversion of sFg into sFn and activation of various intercellular signaling events in circulating blood cells via protease activated receptor-1 (17). Under certain circumstances, thrombin exposure may result in cellular inflammatory responses, such as altered intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression on vascular endothelial cells (ECs) and activation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) (75, 84). The aim of the present study was to elucidate the mechanisms of melanoma cell adhesion within the vascular tumor microenvironment, focusing on the role of thrombin as a factor affecting fibrin formation and melanoma adhesion. By altering their environmental variables, melanoma cells have developed several mechanisms for successful adhesion to the ECs under flow conditions. For example, melanoma cells are known to express high levels of ICAM-1, which is an immunoglobulin superfamily molecule mediating leukocyte firm adhesion to activated ECs (50, 74). Additionally, ICAM-1 has been associated with epithelial carcinogenesis (57). Inhibition of ICAM-1 on TCs of different tissue origins, either by small interfering RNA (siRNA) or blocking monoclonal antibody, led to a strong suppression of tumor invasion (13). Besides ICAM-1, melanoma cells express a variety of integrin molecules, including fibrin(ogen)-receptor integrin αvβ3 (60). Expression of αvβ3 conferred the potential for angiogenesis and metastasis on melanoma (3, 58, 81). An increased level of sFg and sFn around circulating melanoma cells promoted melanoma adhesion, possibly due to the fact that both sFg and sFn are ligands for cells expressing ICAM-1 and αvβ3 (20). In addition, sFn has been shown to enhance melanoma cell adhesion to platelets under flow conditions (7).

PMNs have recently been suggested to play a role in tumor-host interactions. It has been shown that patients with bronchioloalveolar adenocarcinoma have poor clinical outcomes when PMNs infiltrate tumor tissues (80). The role of PMNs in promoting melanoma metastasis has been supported by in vivo investigations (27). In several previous studies, PMNs were suggested to promote melanoma adhesion to the endothelium via ICAM-1 interactions (35, 36, 71, 72). In addition, fibrin(ogen) could bind to CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1) on PMNs in flow (21, 42), thereby facilitating PMN adhesion to the ECs. In light of these previous studies, it remains highly possible that the coagulation process may affect both melanoma direct adhesion to the ECs and PMN-melanoma interactions. However, the mechanism for cooperative regulation of melanoma cell adhesion by immune responses and coagulation events is currently unknown.

A recent study indicated that sFn potentiated melanoma-PMN heterotypic aggregation (83). In the present study, we hypothesize that sFn produced in a tumor microenvironment supports direct melanoma interactions with the endothelium and enhances PMN-facilitated melanoma adhesion within the circulation. In fact, we characterized the dynamics of adhesion using a flow chamber and showed that melanoma cell adhesion to PMNs through sFn was not due to nonspecific capture, but rather a receptor-mediated interaction cross-linking ICAM-1 or αvβ3 on melanoma cells to the ICAM-1 on the endothelium. Here, sFn was made by reacting sFg and thrombin in the presence of anticoagulant, Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro (GPRP). GPRP could bind to fibrinogen D domain, inhibiting transglutaminase cross-linking by changing the glutamine residues in the α and γ chains of fibrinogen (1, 69). It has been shown that GPRP can prolong the fibrinopeptide B release without affecting fibrinopeptide A release kinetics (47). To demonstrate the divalent binding mechanism, sFn was degraded to fragment D by plasmin-limited digestion. Fragment D primarily consists of an intact COOH-terminal stretch of the γ chain containing the ICAM-1, αvβ3, and Mac-1 binding regions. In the presence of fragment D and plasmin-digested sFn, melanoma adhesion was significantly reduced, suggesting that melanoma-EC adhesion requires a divalent binding mechanism.

We further investigated the kinetics of these cross-linking processes and the relative importance of each individual receptor-ligand interaction for successful melanoma adhesion. The tethering experiments showed that melanoma cells initiated interactions with the ECs and PMNs in the presence of sFn. However, the cross-linked sFn bonds formed between Mac-1 on PMNs, and ICAM-1 (or αvβ3) on melanoma cells, were significantly stronger than the cross-linked sFn bonds formed between endothelial ICAM-1 and melanoma ICAM-1 (or αvβ3). These data demonstrate that although sFn increases the frequency of bond formations between melanoma and ECs, PMNs can stabilize these bonds and prolong bond lifetime.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell preparations and reagents.

A375M and 1205Lu metastatic melanoma cells (kindly provided by Dr. Gavin Robertson, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA) were grown in DMEM/F12 (DMEM Nutrient Mixture F12) supplemented with 10% FBS. Adhesion molecule expressions of selected cells were detected by flow cytometry described elsewhere (34) (Table 1). For flow experiments, a confluent monolayer of melanoma cells was detached by using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA, and the detached cells were washed twice in a fresh culture medium. The cells were then suspended in fresh media and allowed to recover for 1 h while being rocked at a rate of 8 rpm at 37°C. For receptor blocking experiments, A375M and 1205Lu cells were pretreated with functional blocking antibodies (anti-αvβ3 or anti-hICAM-1; 5 μg/ml) prior to perfusing the cells into the flow chamber.

Table 1.

Expression levels of ICAM-1 and αVβ3 in the cell lines used in the study

| Geometric Mean Fluorescence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic Potential* | ICAM-1 | αVβ3 | |

| Control IgG | 3.7 ± 0.03 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | |

| 1205Lu | ++++ | 165.5 ± 12.8 | 45.5 ± 1.1 |

| A375M | +++ | 106.7 ± 10.2 | 16.5 ± 0.3 |

Qualitatively determined from the cell line origin; adhesion potential was quantified by comparing relative mean fluorescence levels of ICAM-1 and αvβ3expression by flow cytometry. Values are means ± SE.

PMN preparation has been described in detail elsewhere (37). Briefly, following The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocols (no. 19311), fresh human blood was collected from healthy adults by venipuncture. PMNs were isolated using a Ficoll-Hypaque (Histopaque, Sigma) density gradient method as described by the manufacturer. Isolated PMNs were maintained at 4°C in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% human serum albumin for up to a maximum of 4 h prior to conducting an experiment.

Genetically modified fibroblast L-cells that express stable levels of human E-selectin and ICAM-1 (generously provided by Dr. Scott Simon, University of California Davis, Davis, CA) were used in the present study as a model of the endothelial monolayer substrate (referred as EC). Transfected L-cells express ICAM-1 at a level comparable to IL-1β-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (24).

Mouse IgG antihuman monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against αvβ3 (anti-CD51/61, clone 23C6) and ICAM-1 (clone BBIG-I1) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse antihuman mAbs against Mac-1 (anti-CD11b) and Cell Tracker Green were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP), sFg (Fraction I, type I: from human plasma), GPRP (Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro amide), aprotinin, and BSA were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Bovine thrombin (269,300 U/g) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, Ohio). Fragment D was purchased from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction,VT).

One milliliter of fresh soluble sFn (per 1 × 106 cells) was prepared by incubating 120 μl sFg (25 mg/ml) and 84 μl GPRP (24 mM) with 200 μl of thrombin (from 10 U/ml stock) at 37°C for 5 min prior to perfusion experiments. This method prevents the polymerization of sFn molecules upon thrombin cleavage (10). A twofold concentrated sFn stock solution was mixed with cell suspension (containing melanoma cells and/or PMNs) immediately before perfusion at 1:1 ratio to obtain desired mixture conditions. To obtain other proteins in the mixture, fibrin polymers were formed by reacting 1.5 mg/ml sFg and 2 U/ml thrombin at 37°C for 30 min. Fibrin polymers were removed by swirling with a pipette tip and filtration with 0.2-μm pore filter.

Preparation of fibrin fragments was conducted with limited plasmin digestion of the synthesized fibrin in 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4 (19). Then 0.02 units of plasmin per milligram fibrin(ogen) in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 at 37°C for 2 h was used to cleave sFn. The reaction was stopped by adding 500 KIU aprotinin/U of plasmin.

Flow assays.

The adhesive interactions between 1205Lu cells, PMNs (stimulated with 1 μM fMLP for 1 min before perfusion to the chamber), and EC via sFg or sFn were quantified using a parallel-plate flow chamber system (Glycotech, Rockville, MD). Cell suspensions (1205Lu/PMN at 1:1 ratio of 1 × 106 cells/ml each) were mixed with or without plasma proteins (sFg, sFn, or fragments) and perfused at a desired hydrodynamic shear rate into the flow chamber using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA). After being settled for a period of time at a shear rate of 10 s−1, cells were subjected to an experimental shear rate of 62.5 and 200 s−1, respectively. Phase contrast images of cells near the EC surface were captured and recorded for 3 min at a frame rate of 30 fps and analyzed offline.

Quantification of cell-cell and cell-substrate interactions.

Interactions of circulating cells and EC were classified into three categories: 1) melanoma cell direct arrest on the EC; 2) transient PMN tethering on the EC; and 3) PMN-mediated melanoma cell arrest on the EC. Time scales of these interactions in the presence or absence of sFg or sFn were measured as a means to study the cross-linking adhesion mechanisms. To characterize the dynamics of these interactions, we categorized the durations of interactions (t) into short (1 s < t < 3 s)-, intermediate (3 s < t < 5 s)-, and long (t > 5 s)-term arrests. Although the binding durations of melanoma-EC interactions could be detectable as short as several milliseconds, only the longer tethers (> 1 s), which were anchored by multibonds and contributed to the final melanoma adhesion, were further analyzed. Then, within each time category, the frequency of adhesion of melanoma cells or PMNs on the EC per minute per millimeter squared was quantified. PMN tethering frequency was normalized and expressed by number of tethered PMNs per unit area per unit time (48, 67, 72). In addition, the normalized frequency of melanoma cell binding to the EC monolayer was defined as the number of cell arrest events per unit area and unit time. For PMN-mediated melanoma interaction with the EC, a term of adhesion efficiency was defined as melanoma adhesion efficiency equals the number of melanoma cells arrested on the EC as a result of collision to tethered PMNs in a given duration divided by the total number of melanoma-PMN collisions. The numeration of cell adhesion in each case was confirmed by a second investigator who was not informed of the objective of the case to ensure unbiased measurement.

Tethering experiments for single bond dissociation rate measurement.

To reveal the mechanical properties of these adhesions, tethering experiments were performed to obtain the force-regulated bond dissociation rates by measuring lifetimes of the transient tethers at shear rates of 62.5 and 200 s−1. The A375M cell line was employed for tethering experiments since A375M cells have lower expressions in ICAM-1 and αvβ3 compared with the 1205Lu cells (Table 1). A375M cells were stained with Cell-Tracker Green and resuspended in fibrin solution immediately before the perfusion experiments to minimize prebinding of cell receptors with sFn. The cell suspension was then perfused over the EC in the flow chamber at shear rates of 62.5 and 200 s−1, respectively. The images of tethering experiments were captured with an exposure time of 30–50 ms using fluorescence microscopy and converted to Audio Video Interleave files for further analysis by Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). A total of 100–150 events were analyzed for each case to estimate the apparent bond dissociation rate (koff) by fitting the lifetime to P = 1 − exp(−koff t), where P is the probability of bond formation (2). Only short-term arrests (< 2 s) were used to calculate the dissociation rates (2, 14, 78) as koff was mainly determined by short-term single bond arrests.

To verify a sFn-cross-linking reaction for bond dissociation rate constants, three experiments were performed with the following aims: 1) to measure the koff for (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bond, αvβ3-blocked A375M cells were perfused over the EC; 2) to obtain the koff for (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bond, ICAM-1-blocked A375M cells were perfused over the EC; 3) to get the koff for (Mac-1)-(sFn) bonds, fMLP-activated PMNs were perfused over an sFn-coated surface (2.5 mg/ml sFg was immobilized on the substrate of a flow chamber before being catalyzed by 2 U/ml thrombin for 2 h to generate Fn).

Estimation of bond affinity from a probability model.

To understand the bond kinetics from both association and dissociation rates, we further conducted kinetic simulations based on a well-developed probabilistic theory (15).

| (1) |

Here pn(t) is the probability of having n bonds at time t and kon is the apparent association rate. An apparent binding affinity was determined by Ka = kon/koff. For cell detachment, Eq. 1 was modified by setting the transient probability from 0 to 1 bond as zero. The initial condition is that all arrested cells are most likely linked by only one bond initially (i.e., p1 = 1 and pn = 0 when n = 0, 2, …). Since most of the cells were detached within 5 min, we assumed the remaining arrested cells are linked only by few bonds, and the hydrodynamic force acting on each cell is shared by these bonds. It is important to note that those formed bonds break sequentially following a well-established probabilistic theory (15, 16, 23). A Rung-Kutta numerical scheme and a Levenberg-Marquart method (22, 37) were used to fit the above model to the detachment data with the koff measured by tethering experiments. The probability of short, intermediate, and long arrests (pshort, pinter, and plong) were calculated by Eq. 2 and compared with the experimental results.

| (2) |

where t1 = 1 s, t2 = 3 s, and t3 = 5 s according to the experimental procedure.

Statistical analysis.

All data were obtained from at least three independent experiments and expressed by means ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test or ANOVA. Tukey's test was used in post hoc analysis for ANOVA. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. For tethering experiments, the 95% confidence intervals for regression fitting of unbinding curves were plotted using Sigmaplot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

sFn supports melanoma-endothelium adhesion.

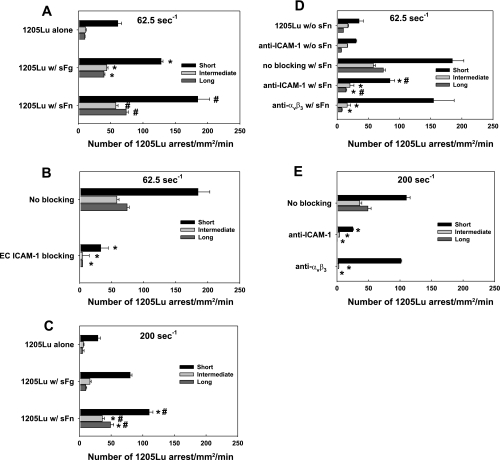

To determine whether sFn mediates melanoma adhesion to ECs, human metastatic 1205Lu melanoma cells were perfused over a confluent EC monolayer expressing ICAM-1. Direct cell adhesion to EC was analyzed and categorized into short-, intermediate-, and long-term arrests, as described in materials and methods to reflect different phases of cell adhesion. Fig. 1, A–C compares the effects of sFg and sFn on melanoma adhesion with respect to the control conditions (without sFg or sFn) at different shear rates (62.5 and 200 s−1).

Fig. 1.

The 1205Lu cells arrest on endothelial cell (EC) is regulated by soluble fibrinogen/soluble fibrin (sFg/sFn), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and fibrin(ogen)-receptor integrin αvβ3. The assessment of melanoma cell arrests were conducted in a parallel-plate flow chamber at shear rates of 62.5 (A–B, and D) and 200 (C and E) s−1, respectively. Each arrest duration was counted with time overlay on video. A: sFn enhanced short-, intermediate-, and long-term melanoma adhesion to EC at 62.5 s−1. B: blocking ICAM-1 on EC abrogated melanoma adhesion to EC via sFn. C: sFn enhanced short-, intermediate-, and long-term melanoma adhesion to EC at 200 s−1. *P < 0.05 compared with the 1205Lu alone case in the same arrest duration. #P < 0.05 compared with the case of 1205Lu with sFg in the same arrest duration. Values are means ± SE for n ≥ 3. D and E: relative roles of melanoma ICAM-1 and αvβ3 in sFn-mediated arrests of 1205Lu on EC as determined by functional blocking antibodies. *P < 0.05 compared with the case of 1205Lu with sFn in the same arrest duration. #P < 0.05 compared with the case of anti-ICAM-1 without sFn in the same arrest duration. Values are means ± SE for n ≥ 3.

The 1205Lu alone interacted minimally with the EC substrate as they only had 60 short-, 17 intermediate-, and 10 long-term arrests within 1 min. Adding 1.5 mg/ml sFg increased the short-term arrests by 50% (Fig. 1A, short), intermediate arrests by 160% (Fig. 1A, intermediate) and long-term arrests of firm cell adhesion by 300% (Fig. 1A, long) at a shear rate of 62.5 s−1. Compared with sFg alone, addition of sFn further increased melanoma arrests at all three time intervals. To determine the role of ICAM-1 on EC in facilitating melanoma adhesion via sFn, ICAM-1 was functionally blocked on the EC by 5 μg/ml mAb before being used as a substrate for cell adhesion. ICAM-1-blocked EC were unable to mediate sFn-bound 1205Lu cell adhesion, while ICAM-1-expressing EC maintained this ability (Fig. 1B). This suggests that EC ICAM-1 is the primary receptor for fibrin(ogen)-mediated melanoma binding to the EC under flow conditions.

Increasing shear rate from 62.5 to 200 s−1 altered the relative contributions of sFg and sFn to the melanoma arrests (Fig. 1C). At 200 s−1, sFn resulted in a marked increase in intermediate- and long-term adhesion frequencies. For intermediate-term adhesion, sFn elevated 1205Lu adhesion by twofold, while sFg did not significantly change melanoma cell adhesion (Fig. 1C, intermediate). sFn also increased the frequency of long-term adhesion by fourfold compared with sFg (Fig. 1C, long). Results from Fig. 1, A–C provide strong evidence for the claim that sFn supports both the initial short-term arrest and long-term firm adhesion at both low and high shear rates.

The relative roles of ICAM-1 and αvβ3 on melanoma cell sFn cross-linked adhesion to ICAM-1 on the EC were determined by functionally blocking the respective receptors on the melanoma cells before perfusion at 62.5 and 200 s−1 in the presence of sFn (Fig. 1, D and E). Short-term melanoma-EC interactions were shown to be mainly mediated by ICAM-1 on the melanoma cell, since blocking ICAM-1 reduced sFn-mediated adhesions by > 50%, while blocking αvβ3 had less significant effects. Blocking ICAM-1 or αvβ3 prevented intermediate and long-term melanoma adhesions, suggesting ICAM-1 and αvβ3 expressed on melanoma cells are required for longer-term sFn-mediated adhesions to the EC under shear conditions. Other receptors did not seem to play a role in sFn-mediated 1205Lu attachment, since when ICAM-1 and αvβ3 were blocked simultaneously, there were no cell arrests at both 62.5 and 200 s−1 (data not shown).

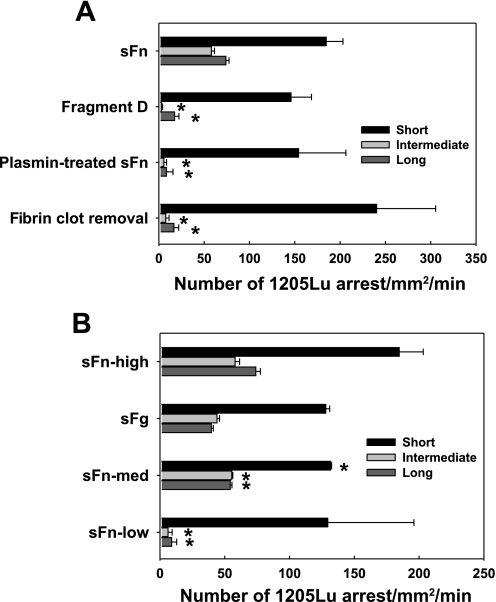

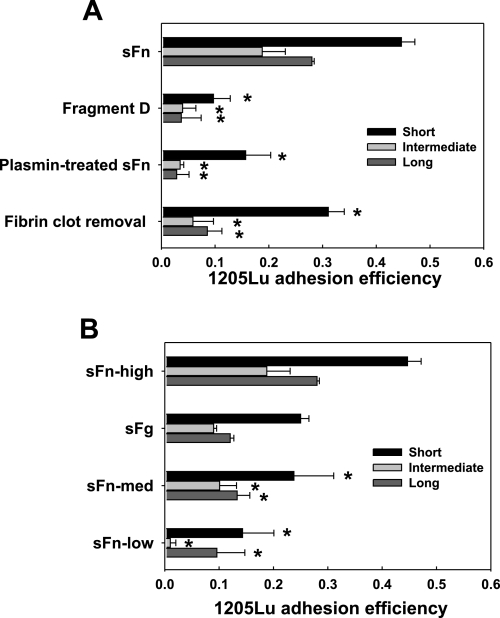

sFg is a glycoprotein that comprises two sets of three polypeptide chains, Aα, Bβ, and γ, linked together by 29 disulfide bonds. This dimerization brings together two identical binding sequences and makes fibrin(ogen) a divalent ligand. To test whether this divalent ligand-mediated cross-link binding would be important for melanoma direct adhesion, sFn was cleaved by plasmin to fragments E and D. Fragment D consists of one set of COOH terminals of Aα, Bβ, and γ chain, involving two αvβ3 , two Mac-1, and one ICAM-1 binding sites. When sFn was replaced with fragment D, the intermediate and long-term melanoma arrests were significantly reduced (Fig. 2A). Likewise, plasmin-treated sFn failed to mediate melanoma adhesion. Other proteins in the sFn solution (which was readily obtained by first allowing fibrin to polymerize, removing fibrin polymers with filtration, and then adding GPRP) were also incapable of inducing melanoma adhesion, suggesting intact sFn was the only mediator to facilitate melanoma direct adhesion to the EC. Low thrombin levels partially converted sFg to sFn. In the presence of 0.053 U/ml thrombin-generated sFn, melanoma adhesion frequencies were significantly reduced for all arrest durations (Fig. 2B). Compared with sFn made by 1.5 mg/ml sFg, sFn from 15 μg/ml sFg was incapable of mediating cell firm adhesion.

Fig. 2.

sFn-mediated melanoma adhesion to EC is dependent on a divalent binding mechanism. A: fibrin(ogen) fragment D, which contains a half of α, β, and γ chains, plasmin-digested sFn, and residual proteins after fibrin polymer removal, failed to mediate 1205Lu intermediate and long-term adhesion to EC, although still supporting short-term adhesion. B: thrombin and fibrinogen concentrations affect melanoma adhesion. sFn-high, sFn-med, and sFn-low were made, respectively, from 1.5 mg/ml sFg + 2 U/ml thrombin; 1.5 mg/ml sFg + 0.053 U/ml thrombin; and 0.015 mg/ml sFg + 2 U /ml thrombin. sFg was 1.5 mg/ml sFg without adding thrombin. *P < 0.05 compared with the case sFn (A) or sFn-high (B), respectively, in the same arrest duration. Values are means ± SE for n ≥ 3.

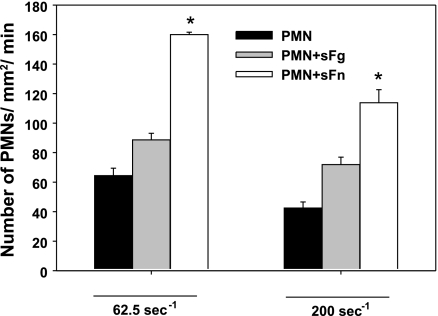

sFn enhances PMN tethering to endothelial ICAM-1.

Activated PMNs were shown to facilitate the melanoma adhesion to the endothelium via adhesive interactions between β2 integrin (LFA-1 and Mac-1) on PMN and ICAM-1 on melanoma cells (36, 71). PMNs exhibited enhanced rolling, tethering, and adhesion to the EC. fMLP stimulation has been shown to upregulate Mac-1 expression level by ninefold (70). Therefore, to exclude the potential activation of PMNs by thrombin, PMNs were prestimulated by fMLP before being perfused into the flow chamber. To probe possible roles of sFn cross-linking in PMN adhesion to ECs, PMN tethering to the ICAM-1 was quantified. Results from Fig. 3 show that sFn increases PMN adhesion by twofold at a shear rate of 62.5 s−1. Increasing shear rate significantly decreases the PMN tethering frequency. Our results are consistent with findings from previously published work (33), suggesting that sFn plays a more important role than sFg in mediating activated PMN firm adhesion to the EC under high shear conditions. When ICAM-1 was blocked, the lifetime of PMN arrests on the EC decreased, and cells displayed fast rolling velocities (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

sFg or sFn affects polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) arrest on EC at different shear rates. *P < 0.05 compared with the case PMN and PMN+sFg in the same time interval. Values are means ± SE for n ≥ 3.

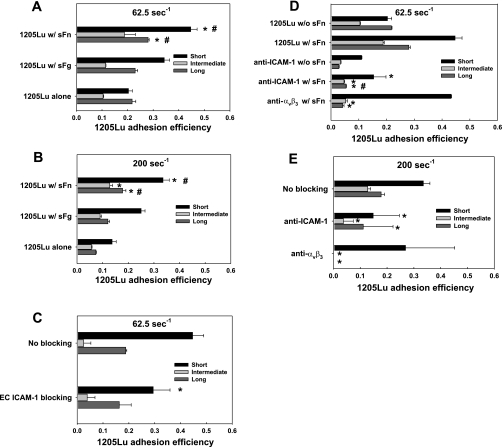

sFn regulates PMN-facilitated melanoma adhesion to ICAM-1.

To evaluate the role of sFn on PMN-mediated melanoma cell adhesion to the endothelium, the ability of 1205Lu cells to interact with adherent PMNs on the EC was quantified, in terms of adhesion efficiency (defined in the materials and methods). Adhesion efficiency was used here because not all melanoma-PMN collisions could successfully result in aggregate formations on the EC under flow conditions. To compare the cases of PMN-facilitated melanoma adhesion and direct melanoma adhesion to the EC, the time durations that melanoma-PMN aggregates stayed in a close proximity of the EC were categorized into short-, intermediate-, and long-term arrests. We showed that sFn significantly enhanced the rolling, tethering, and arrest of PMNs on the EC monolayer (Fig. 3). This increased the probabilities of PMN-1205Lu cell collisions, which further facilitated 1205Lu adhesion to the EC under flow conditions. From our observations, the process of PMN-facilitated melanoma adhesion follows three steps: 1) a melanoma cell from upstream collides with a tethered PMN; 2) the melanoma cell transiently adheres to a tethered PMN; and 3) the melanoma cell arrests on the EC by forming an aggregate with a tethered PMN.

sFg significantly increased short-term PMN-mediated 1205Lu adhesion efficiency at 62.5 s−1 (0.34 ± 0.020 compared with 0.20 ± 0.015 from the control) and 200 s−1 (0.25 ± 0.015 compared with 0.13 ± 0.016 from the control) (Fig. 4, A and B). However, sFg did not significantly affect intermediate and long-term adhesion efficiency of melanoma cells. Compared with sFg under both shear conditions, sFn increased the short-term adhesion efficiency by more than twofold (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast to direct melanoma adhesion (Fig. 1A), sFn did not significantly increase long-term PMN-mediated melanoma adhesion at a relatively low shear rate of 62.5 s−1, but promoted sustained adhesion at a high shear rate of 200 s−1 (Fig. 4, A and B). It was noted that even when ICAM-1 on EC was inhibited, intermediate and long-term melanoma adhesion efficiencies were not significantly affected, although the absolute frequency of melanoma tethering via PMN was reduced (Fig. 4C). This might be due to the fact that PMN-mediated melanoma adhesion efficiency was dependent on sFn cross-linking between PMNs and melanoma cells, which was not affected by the ICAM-1 blocking on the EC.

Fig. 4.

PMN-facilitated 1205Lu adhesion is affected by fibrin(ogen). sFn enhanced short-, intermediate-, and long-term PMN-mediated melanoma adhesion at 62.5 s−1(A) and 200 s−1 (B). C: blocking ICAM-1 on EC abrogated PMN-mediated 1205Lu adhesion in the presence of sFn. *P < 0.05 compared with the 1205Lu alone case in the same arrest duration. #P < 0.05 compared with the case 1205Lu with sFg in the same arrest duration. Values are means ± SE for n ≥ 3. D–E: relative roles of ICAM-1 and αvβ3 in PMN-mediated 1205Lu adhesion in the presence of sFn. *P < 0.05 compared with the 1205Lu with sFn case in the same arrest duration. #P < 0.05 compared with the anti-ICAM-1 without sFn case in the same arrest duration. Values are means ± SE for n ≥ 3.

To assess the role of sFn receptors in melanoma adhesion efficiency, we functionally blocked ICAM-1 and αvβ3, respectively, on the melanoma cells and quantified the adhesion efficiency at shear rates of 62.5 and 200 s−1, respectively. Results from Fig. 4, D and E showed that the short-term PMN-melanoma interactions were apparently initiated by an engagement of ICAM-1 on melanoma (TC) and Mac-1 on PMN cross-linked by sFn, while (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(Mac-1)PMN bonds could prolong the lifetime of PMN-enhanced melanoma adhesion.

To verify the divalency of sFn-mediated binding, sFn (0.053 U/ml thrombin) in the binding solution used in the above adhesion assays was replaced by 1.5 mg/ml fragment D from sFn or plasmin-digested sFn. Binding for all arrest durations was prevented, suggesting that sFn-mediated PMN-melanoma aggregation follows a divalent cross-linking mechanism (Fig. 5A). This binding was specific, since other proteins did not facilitate any binding after fibrin polymers were removed. sFn made from a low concentration of thrombin (0.053 U/ml) did not significantly increase the magnitude of PMN-mediated adhesion compared with 1.5 mg/ml sFg alone without thrombin (Fig. 5B). In sharp contrast to higher sFn concentration, lower sFn concentration effectively reduced melanoma adhesion efficiency (Figs. 4A vs. 5B). This may imply that low concentrations of sFn weakened the binding between ICAM-1 and Mac-1 and/or between ICAM-1 and LFA-1, thereby inhibiting PMN-mediated melanoma adhesion.

Fig. 5.

PMN-mediated melanoma adhesion in the presence of sFn is dependent on a divalent binding mechanism. A: fibrin(ogen) fragment D failed to mediate PMN-facilitated 1205Lu adhesion to EC. B: thrombin and fibrinogen concentrations affect melanoma cell adhesion. sFn-high, sFn-med, sFn-low were made, respectively, from 1.5 mg/ml sFg + 2 U/ml thrombin; 1.5 mg/ml sFg + 0.053 U/ml thrombin; and 0.015 mg/ml sFg +2 /ml thrombin. sFg was 1.5 mg/ml sFg without adding thrombin. *P < 0.05 compared with the case sFn (A) or sFn-high (B), respectively, in the same arrest duration. Values are means ± SE for n ≥ 3.

Bond apparent dissociation rates and affinities reflect relative contributions of ICAM-1 and αvβ3.

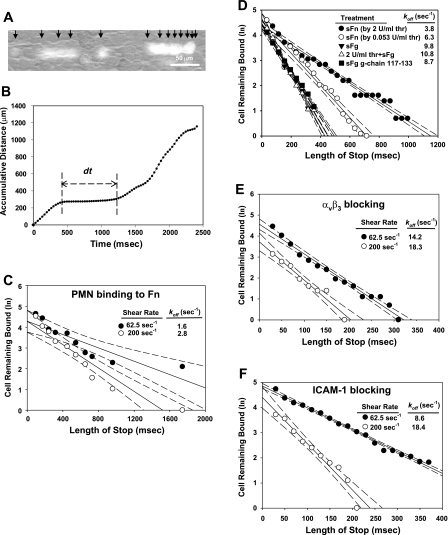

Apparent dissociation rate koff for sFn receptors ICAM-1, αvβ3, and Mac-1 were determined by single bond tethering assay (26, 59). As is shown in Fig. 6A, the trajectories and locations of fluorescently labeled cells in each frame could be conveniently tracked by Image-Pro Plus. The algorithm in the software correlated the cell positions in a series of frames, and cell accumulative distance was plotted as a function of time (Fig. 6B). The plateau in the curve represents the lifetime of the bond (indicated as dt). Adhesion of fMLP-stimulated PMNs on immobilized sFn had a koff of 1.60 s−1 at a shear rate of 62.5 s−1 and 2.83 s−1 at 200 s−1 (Fig. 6C). These values fall into a range of the force-free dissociation rate of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) and selectin interactions (1∼10 s−1) (41). Since Mac-1 is the only known receptor for sFn on PMNs, these koff values for (Mac-1)-(sFn) bonds might indicate that shear force had very little effect on this type of bond, since a 95% confidence level of the values measured at 62.5 and 200 s−1 overlapped (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Kinetics dissociation rates (koff) measured by single bond tethering experiments. A: typical composite fluorescence images showing trajectories of a tethered cell during 360 ms. Individual frames captured with Streampix (NorPix) were stacked using the ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Cell velocities became smaller when the cell attached to the EC monolayer. Black arrows indicated the positions of cells in each frame. B: plot of cumulative distance a cell traveled tracked by Image-Pro Plus. The plateau reflected the duration of cell arrest (indicated as dt). C: dissociation rate constant of Mac-1 binding to sFn was measured by perfusing fMLP-stimulated PMNs over sFn coated surface. D: koff values for sFn (made from 0.053 U/ml and 2 U/ml thrombin, respectively) and sFg-initiated A375M adhesive bonds. E–F: koff values for αvβ3 (by blocking ICAM-1) and ICAM-1 (by blocking αvβ3), respectively, were determined by perfusing A375M cells over EC in the presence of sFn. For first-order dissociation kinetics for transient tethers, the negative slope indicates koff. Each data point represents the average value from 3 independent experiments.

A375M melanoma cells were used to evaluate the apparent koff for (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bonds, (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bonds, or the combination of these two bonds. When sFn (made from 0.053 or 2 U/ml thrombin) instead of sFg was introduced, the bindings became stronger as koff dropped from 9.8 s−1 to 6.3 or 3.8 s−1 (Fig. 6D). Thrombin alone had no effect on melanoma bond affinity, as the value of koff of sFg-initiated bonds was not reduced upon exposure of A375M melanoma cells to 2 U/ml thrombin (koff 9.8 s−1 for sFg vs. 10.8 s−1 for 2 U/ml thrombin + sFg). To determine whether ICAM-1 binding sites for sFg or sFn were responsible for bond strength, cells were pretreated with fibrinogen γ chain 117–133 peptides prior to the tethering assay in the presence of sFn. γ chain 117–133 pretreatment significantly increased the koff of sFn-initiated bonds (3.8 vs. 8.7 s−1) (Fig. 6D).

The koff values of αvβ3-mediated bonds (by blocking ICAM-1; Fig. 6E) and of ICAM-1-mediated bonds (by blocking αvβ3; Fig. 6F) were augmented with an increase in shear rates. The value of koff for αvβ3 was increased by 46% at 200 s−1, while that for ICAM-1 was only increased by 29% (Fig. 6, E–F). Also, at 62.5 s−1, αvβ3-initiated bonds had a koff of 8.6 s−1, which was much smaller than koff of ICAM-1, 14.2 s−1. Since the dissociation rate reflects the lifetime of the bonds, it is likely that fibrin-cross-linked (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bonds were more prone to dissociation than (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bonds. High shear rates exerted a larger tensile force on the bonds, which resulted in an increased bond dissociation rate (Fig. 6, E and F). These two sFn-cross-linked bonds had similar koff values of 18.3 and 18.4 s−1 at the shear rate of 200 s−1, which might imply that these bonds contribute equally to melanoma adhesion to the EC through a sFn-cross-linking mechanism at high shear rates. The values of koff measured for (αvβ3)TC-(sFn) or (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn) bonds were comparable to those of previously measured dissociation rates of monocyte adhesion to the ECs (e.g., 15 s−1 at a shear rate of 40 s−1) and slightly larger than those for β2-integrin-ICAM-1 bonds (e.g., 0.03–2.5 s−1) (22, 23, 67, 82). Therefore, the deviation of koff magnitude of sFn-mediated bonds might reflect the general behavior of divalent ligand-cross-linked bonds. The measured values most likely depend on the experimental approaches and data analyses, but these values fall in the range of P-selectin and PSGL-1 bonds (2, 63).

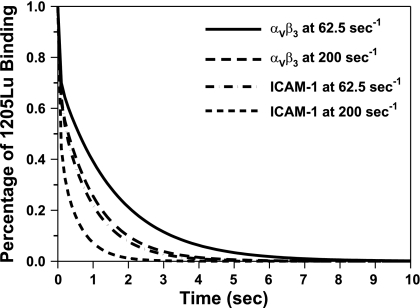

We also incorporated the values of koff from tethering experiments into a probability model (Eq. 1 and 2) to derive the apparent binding affinity Ka for sFn-cross-linked bonds (Table 2). It was found that the affinity of the αvβ3-cross-linked bond was higher than that of ICAM-1 (2.98 vs. 2.22 s−1 at shear rate 62.5 s−1, and 3.08 vs. 1.32 s−1 at shear rate 200 s−1). Fig. 7 shows the best-fitting result for 1205Lu cells arrested on EC at shear rates of 62.5 and 200 s−1.

Table 2.

Summary of apparent dissociation rate (koff) and affinity (Ka) values calculated for individual receptors-soluble fibrin (sFn) bonds at shear rates of 62.5 s−1 and 200 s−1

|

koff (s−1) |

Ka |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62.5 s−1 | 200 s−1 | 62.5 s−1 | 200 s−1 | |

| ICAM-1 | 8.6 | 18.4 | 2.22 | 1.32 |

| αvβ3 | 14.2 | 18.3 | 3.98 | 3.08 |

| Mac-1 | 1.6 | 2.8 | ||

Mac-1: CD11b/CD18.

Fig. 7.

Predicting the 1205Lu-endothelium binding using a kinetic model (Eq. 1 and 2). Values of dissociation rates (koff) were adapted from tethering experiments measurement (Table 2). Percentage of 1205Lu remaining bound for αvβ3 and ICAM-1 bonds is obtained by fitting data in Fig. 1, D and E, where ICAM-1 and αvβ3 were blocked, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that PMN-facilitated melanoma cell adhesion on EC follows a multistep scheme, where cell adhesion is initiated by LFA-1-mediated tethering onto endothelial ICAM-1 and is further stabilized by Mac-1 on activated PMNs (36, 71, 72). Elevated sFn levels are a characteristic property of the tumor microenvironment (8). Therefore, examining sFn-mediated cross-linking mechanisms would generate valuable information about the complex intermolecular events in TC extravasation.

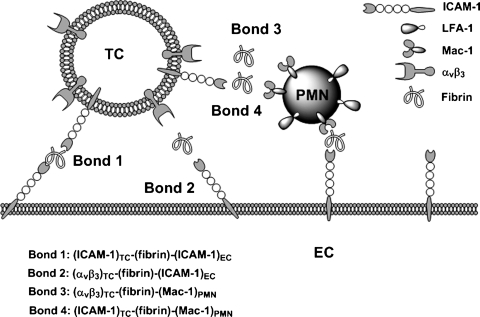

In the present study, we showed that: 1) sFn serves as a divalent cross-linking ligand, tethering melanoma cells to the ECs; 2) sFn increases the force-regulated lifetime to a larger extent than sFg; 3) a high shear force has a larger impact than a low shear force on the enhancement of both long-term melanoma direct-adhesion frequency and PMN-mediated melanoma adhesion efficiency in the presence of sFn; 4) the promoting effect of sFn on melanoma cell adhesion is most apparent for initial TC capture and firm adhesion under shear conditions; and 5) ICAM-1 plays an important role in initial melanoma tethering, while αvβ3 mediates firm adhesion of melanoma cells to the endothelium. The effect of sFn is additive with that of PMN-mediated melanoma firm adhesion to the endothelium (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of receptor-ligand pairings with sFn as a cross-linking molecule. When ICAM and αVβ3 bearing melanoma cells approach ICAM-1 bearing ECs and Mac-1 bearing PMNs, 4 types of bonds (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC, (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC, (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn)-(Mac-1)PMN, and (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(Mac-1)PMN via freely flowing sFn molecules could form. ICAM-1-mediated bonds initiated short-term tethering, while αvβ3 -mediated bonds were responsible for firm adhesion of melanoma cells to either EC or PMN.

Fibrin, by cross-linking receptors, potentiates PMN-mediated melanoma firm adhesion to EC under high shear.

Elevated expression of TF, a membrane spanning procoagulant protein on melanoma cell membranes, leads to elevated levels of both sFn and fibrin polymers on primary tumor loci (51). Polymeric fibrin has been shown to form a protective sheath around circulating TCs and leads to the formation of clusters that prevent from natural killer cell invasions, facilitating circulating TCs lodging to distant organ sites (53). Considering the vascular size restrictions and plasma skimming effects, it is less likely to find melanoma clusters formed by a fibrin clot in small capillaries. This is due to the fact that thrombin-mediated fibrin formation is a rapid event. Once thrombin is generated in plasma, fibrinogen is quickly cleaved and polymerized (11). It is difficult to determine whether fibrin monomers or fibrin clots would be more important to tether TCs. Our adhesion assays, which employ fibrin monomers generated by reacting sFg and thrombin in the presence of the anticoagulant peptide GPRP, are a simplified model system. Furthermore, it is difficult to characterize fibrin polymer-mediated binding inside a parallel-plate flow chamber since polymerization may alter the medium viscosity and affect the flow field. We have demonstrated that other proteins, including GPRP after fibrin clot removal, have no effects on either melanoma direct adhesion or PMN-mediated melanoma adhesion to the EC (Figs. 2A and 5A). To obtain more definitive evidence for sFn-dominated binding, the potential roles of other proteins in this process were excluded after the fibrin polymer was removed. This result demonstrated that applications of 2 U/ml thrombin could convert all fibrinogen to fibrin; otherwise residual fibrinogen would have increased 1205Lu adhesion. Residual thrombin did not seem to activate melanoma adhesion. This was examined in a tethering assay that showed pretreating melanoma with 2 U/ml thrombin did not result in long-term bonds (Fig. 6D). However, another group showed that tumor-platelet aggregation was initiated by using 1–10 mU/ml thrombin (52). These results are plausible as melanoma adhesion to fibrin(ogen) proceeds through distinct receptors whose expression and affinity are sensitive to thrombin stimulation.

The tumor stroma has been characterized by the generation of tumor-derived plasminogen, which is a precursor of plasmin that can degrade fibrin to small fragments (68). These proteolytic fragments contain four RGD motifs, two located in the αC region and two in the coiled-coil connector. In the present study, an effort was made to verify these divalent binding mechanisms. When sFn was replaced with fibrinogen fragment D or plasmin-treated sFn at the same molecular level, the enhancement of melanoma adhesion was eliminated. This result emphasized the requirement of double chains for receptor-mediated adhesion. It is important to note that fragment D contains two αvβ3 binding sites, one at decapeptide and the other at Aα 572–575, which might have the potential for receptor-receptor cross-linking. However, in the present study, we found no effect of fragment D on melanoma cell adhesion, particularly for long-term arrest. This may be caused by spatial hindrance, where the binding to one site masks binding to others. It is conceivable that the adhesive behavior between intact fibrin(ogen), fragment D and fragment γ chain 117–133 is different due to the ability of plasmin to cleave sFn (20).

sFn has been shown to enhance melanoma firm adhesion by 7.4-fold at 62.5 s−1 and by fourfold at 200 s−1 (Fig. 1, A and C) compared with sFg. However, sFn only significantly increased PMN-mediated melanoma firm adhesion at 200 s−1, not at 62.5 s−1 (Fig. 4, A and C). This is consistent with earlier observations showing that, in contrast to selectins, fibrinogen does not have a role in the initial seeding of TCs within the pulmonary vasculature. Rather, fibrinogen may regulate metastasis by mediating the sustained adhesion and survival of TCs under high shear (54). Varying durations of TC adhesion at different shear rates suggest that fibrin-initiated bonds may have substantial tensile strengths that could lead to bonds with increased lifetimes at high shear rates. Additionally, the small compliance distance may be an indication of large bond stiffness for long-term binding, which could resist large rupture forces.

It has been reported that fibrinogen binding to the lipid bilayer immobilized αIIbβ3, results in a time-dependent two-step process, where an initial reversible bond is stable and dissociated only in the presence of high levels of Arg-Gly-Asp-Val (RGDV) (39, 40, 46). It has also been reported that loading rates and contact time have a large impact on αIIbβ3-fibrinogen rupture force (39). In the present study, we have shown that αvβ3-fibrin binding is shear rate-dependent. αvβ3 is structurally similar to αIIbβ3 whose affinity or activation state can be regulated by Mn2+ and activating mAbs. Therefore, the apparent force-regulated binding behavior to fibrin(ogen) might be regulated by αvβ3 activating states.

Roles of receptors in sequential binding of melanoma to PMN and endothelial cells.

When β2 integrins are activated, they become high-affinity receptors for sFg (20). The high-affinity regions for ICAM-1 and αvβ3 on sFn are located on their γ chains. ICAM-1 expression is upregulated on the EC in response to an inflammatory microenvironment, thus becoming accessible to sFn and melanoma cells (73). Results from Fig. 1, A–C suggest that both sFg and sFn increase melanoma-EC interactions under flow conditions, although sFn had a stronger ability to mediate long-term arrest at a higher shear rate. This may imply that the extra exposed binding sites on sFn modify the kinetics of the bonds (43). Earlier studies focusing on melanoma cell adhesion to immobilized fibrinogen have revealed an αvβ3-dependent mechanism (60). Blocking ICAM-1 on melanoma cells reduced the frequency of TC arrest on the ECs (Fig. 1D), but blocking αvβ3 mainly reduced the intermediate and long-term interactions.

One solution to the limitations of cell-based flow assay is to biophysically dissect the role of each receptor at a single bond level. As an alternative approach, we proposed a new experimental procedure and a theoretical model to extract kinetic rate constants (2, 6). Based on the tethering assays developed, we were able to show that ICAM-1 and αvβ3 had different dissociation rates at a shear rate of 62.5 s−1. The values of koff measured for these bonds [i.e., (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC and (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC, ranging from 10 to 20 s−1] were higher than those measured for β2 integrin-(ICAM-1) bonds (<1 s−1) (22, 23, 29, 37, 82) but were in line with those for selectin-ligand bonds and vWF-GPIb bonds (2, 14, 32, 41, 62, 63). This may reflect general biophysical properties of these types of divalent ligand-cross-linked bonds. To clarify this process, we assumed sFn-cross-linked bonds could dissociate in two ways (Fig. 6). For example, cell surface receptors A (e.g., ICAM-1 on EC) and B [e.g., αvβ3 on melanoma (TC)] can bind to each other via sFn in a way that

| (3) |

where kon1 and koff1 are association rate and dissociation rate, respectively, for A-sFn bond, and kon2 and koff2 are association rate and dissociation rate for B-sFn bond, respectively. For the tethering experiments described above (assuming a single bond dissociation), the probability that a cell remains bound (P) is dP/dt = − (koff1 + koff2)P with a solution, ln(P)/t = (koff1 + koff2). The apparent dissociation rate (koff1+ koff2) can be determined by an unbinding curve, which plots the logarithm of the number of cells that remain bound after stop time length t according to Eq. 2 (59). We thereafter assumed that koff for (ICAM-1)-(sFn) bonds would be one half of the value of koff for (ICAM-1)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bonds (14.2 s−1) based on the cross-linking model. Therefore, koff for (ICAM-1)-(sFn) bonds is 7.1 s−1. By subtracting koff for (ICAM-1)-(sFn) bonds (7.1 s−1) from koff for (αvβ3)TC-(sFn)-(ICAM-1)EC bonds (8.6 s−1), we obtained koff for (αvβ3) TC-(sFn) bonds (5.5 s−1), although these values need to be further verified by other techniques, such as atomic force microscopy or optical tweezers. We have found that αvβ3 has a larger compliance distance than ICAM-1, since its dissociation rate has larger changes than that of ICAM-1. Therefore, ICAM-1-mediated bonds might be more compliant than αvβ3-mediated bonds, which would make them more adaptable to shear. The distinct dissociation rates of αvβ3 and ICAM-1 might clearly define their respective roles in sequential adhesion of melanoma. The critical role ICAM-1 played in initial melanoma tethering is evidenced by the reduction of melanoma adhesion frequencies for all arrest durations following the blocking of ICAM-1 (Figs. 1D and 5D). This was further proven as the ICAM-1 binding site, γ chain fibrinogen decapeptide LGGAKQAGDV, reduced the bond lifetime and increased koff (Fig. 6D).

Although we were unable to quantify the association rate and affinity directly from the tethering assay, a kinetic model was further applied to obtain the apparent affinity by comparing the short-, intermediate-, and long-term arrest data (Fig. 7). The percentage of TCs remaining bound decreases very rapidly in the first 0.1 s, implying that the adhesion could most likely be mediated by only one single bond. That is why only the events with lifetimes < 1 s were counted for the tethering experiments of a single bond dissociation rate measurement. In contrast, the adhesion events > 1 s are more important for the experiments of melanoma cells' and PMNs' arrests on the endothelium, which will, in turn, support the extravasation.

Possibility of involvement of other receptors and cell types.

In our study, we have focused on three important sFn receptors: Mac-1, ICAM-1, and αvβ3. Other groups reported that CD44 could also bind to fibrin (4, 5). CD44 is a glycofucosylated molecule, which has been shown to be expressed on the surface of colon carcinoma cells and acts as a PSGL-1-like receptor on TCs. In comparison, melanoma cells only express the standard isoform of CD44 (CD44s) (83). Our present studies have shown that a substantial decrease in melanoma cell adhesion occurs in the presence of sFn upon blocking ICAM-1 and αvβ3 (Fig. 1C), suggesting that CD44s might contribute less to melanoma tethering and firm adhesion with the current experimental sFn concentrations and shear rates. The synergistic roles of different receptors under shear conditions have also been studied for CD44, selectin, and fibrin bonds (64). In a previously published study (52), the CD44-(P-selectin) bond was found to have a longer unstressed lifetime, which has a lower susceptibility to bond rupture under force and a higher tensile strength than CD44-fibrin bonds capable of mediating binding under higher hydrodynamic forces.

The EC monolayer used in the present studies, expressing only E-selectin and ICAM-1, is a rather simplified endothelial system for a cell adhesion study and has limitations. For example, actual endothelial cells, like HUVECs, may express other kinds of receptors, like VCAM-1, P-selectin, and αvβ3, which could bind to sFn, melanoma cells, and/or PMNs (16, 45). The local Reynolds number around the adherent cells (31) or slight cell sedimentation (79) may also affect the shear force exerted on bonds and cell adhesion frequency. Despite all of these possible limitations, studying cell adhesion in a simple parallel-plate flow system still provides important insights to cell adhesive behavior under hydrodynamic shear conditions. Future studies can be carried out to elicit the contributions of other factors.

Platelets and monocytes may also play important roles in TC adhesion and metastasis (10, 18, 49, 61). Other studies reported the importance of macrophages in cancer and immune recognition, focusing on the extravascular tissue space (76). However, few reports are focused on the mechanisms by which neutrophils and fibrin-mediated cross-linking potentially affect TC adhesion to the endothelium within the intravascular circulation, which could significantly influence subsequent TC extravasation during metastasis.

It was widely believed that the role of fibrin in tumor metastasis lies in its cytotoxicity protection where fibrin may polymerize and form a coat around tumors, which makes them inaccessible to immune cells. An in vitro study with plasma suggested a strong immune protective effect of sFn on tumors from natural killer cells and lymphocyte-activated killer cytotoxicity (25). In addition, sFn was shown to inhibit natural killer cell, monocyte, and lymphocyte attack, which was due to blockade of immune cell adherence to cancer cells (9, 53, 55, 56). An in vivo study suggested that fibrin is a determinant component of metastatic potential (54). Fibrin could inhibit longer-term adhesion in the lung up to 1 h without affecting short-term tumor retention. In addition, in natural killer cell-depleted mice, fibrinogen was no longer a metastatic potential determinant (25, 55, 56). These interesting studies suggest some link between fibrin and immune killing. Although these papers disclosed the necessity of immune protective mechanism mediated by fibrinogen to facilitate tumor metastasis, they did not rule out any possible roles of fibrin-facilitated TC adhesion and extravasation in metastasis. In contrast, recent studies by Konstantopoulos and colleagues (4, 5, 30, 31) have clearly shown an important role of fibrinogen/fibrin in mediating colon carcinoma cell adhesion, which actually supports an adhesion mechanism. In addition, several in vivo studies have already reported an important role of fibrinogen and/or fibrin in platelet-mediated TC adhesion in metastasis (7, 19). While the role of platelets in cancer metastasis has been widely investigated earlier, especially involving fibrinogen/fibrin, our present study has focused on how neutrophils and fibrin(ogen) modulate melanoma cell adhesion to the endothelium.

Future in vivo work needs to be conducted to fully validate the role of fibrinogen/fibrin in TC adhesion and extravasation, especially for their interactions with neutrophils and the endothelium. Some recent in vivo studies have provided evidence on the role of neutrophils in mediating melanoma cell retention in the lung microvasculatures and subsequent metastasis (27, 38). In conclusion, this is the first study that characterizes soluble ligand-mediated melanoma adhesion to endothelial cells under flow conditions and determines the kinetics of specific sFn-cross-linked bonds. Delineation of biophysical interactions between fibrin(ogen) and receptors at the molecular level can shed light toward the potential development of treatment for melanoma metastasis.

GRANTS

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant CA-125707 and National Science Foundation Grant CBET-0729091 (to C. Dong). We also thank the Turkish Government Ministry of Education for the scholarship (to T. Ozdemir).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.O. and P.Z. performed experiments; T.O., P.Z., and C.F. analyzed data; T.O., P.Z., and C.F. interpreted results of experiments; T.O., P.Z., and C.F. prepared figures; T.O., P.Z., and C.F. drafted manuscript; T.O., P.Z., C.F., and C.D. edited and revised manuscript; T.O., P.Z., C.F., and C.D. approved final version of manuscript; T.O., P.Z., and C.D. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Scott I. Simon for kindly providing transfected fibroblast L-cells. We are also grateful to Dr. Justin Brown, Lauren Harter, Eric Weidert, Kelly Layton and Bryan Sutermaster for critical reading and Dr. William A. Hancock and Dr. Hari Muddana for insightful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Achyuthan KE, Dobson JV, Greenberg CS. Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro modifies the glutamine residues in the α-chain and γ-chains of fibrinogen-inhibition of transglutaminase cross-linking. Biochim Biophys Acta 872: 261– 268, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alon R, Hammer DA, Springer TA. Lifetime of the P-selectin-carbohydrate bond and its response to tensile force in hydrodynamic flow. Nature 374: 539– 542, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Altieri DC, Duperray A, Plescia J, Thornton GB, Languino LR. Structural recognition of a novel fibrinogen γ-chain sequence (117–133) by intercellular-adhesion molecule-1 mediates leukocyte-endothelium interaction. J Biol Chem 270: 696– 699, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alves CS, Burdick MM, Thomas SN, Pawar P, Konstantopoulos K. The dual role of CD44 as a functional P-selectin ligand and fibrin receptor in colon carcinoma cell adhesion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C907– C916, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alves CS, Yakovlev S, Medved L, Konstantopoulos K. Biomolecular characterization of CD44-fibrin(ogen) binding distinct molecular requirements mediate binding of standard and variant isoforms of Cd44 to immobilized fibrin(ogen). J Biol Chem 284: 1177– 1189, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bell GI. Models for specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science 200: 618– 627, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biggerstaff JP, Seth N, Amirkhosravi A, Amaya M, Fogarty S, Meyer TV, Siddiqui F, Francis JL. Soluble fibrin augments platelet/tumor cell adherence in vitro and in vivo, and enhances experimental metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 17: 723– 730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biggerstaff JP, Seth N, Amirkhosravi A, Amaya M, Fogarty S, Meyer TV, Siddiqui F, Francis JL. Soluble fibrin augments platelet/tumor cell adherence in vitro and in vivo, and enhances experimental metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 17: 723– 730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biggerstaff JP, Weidow B, Dexheimer J, Warnes G, Vidosh J, Patel S, Newman M, Patel P. Soluble fibrin inhibits lymphocyte adherence and cytotoxicity against tumor cells: implications for cancer metastasis and immunotherapy. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 14: 193– 202, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Biggerstaff JP, Weidow B, Vidosh J, Dexheimer J, Patel S, Patel P. Soluble fibrin inhibits monocyte adherence and cytotoxicity against tumor cells: implications for cancer metastasis. Thromb J 4: 12, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blomback B, Hessel B, Hogg D, Therkildsen L. A two-step fibrinogen-fibrin transition in blood coagulation. Nature 275: 501– 505, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruggemann LW, Versteeg HH, Niers TM, Reitsma PH, Spek CA. Experimental melanoma metastasis in lungs of mice with congenital coagulation disorders. J Cell Mol Med 12: 2622– 2627, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cairns RA, Khokha R, Hill RP. Molecular mechanisms of tumor invasion and metastasis: an integrated view. Curr Mol Med 3: 659– 671, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen SQ, Springer TA. Selectin receptor-ligand bonds: formation limited by shear rate and dissociation governed by the Bell model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 950– 955, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chesla SE, Selvaraj P, Zhu C. Measuring two-dimensional receptor-ligand binding kinetics by micropipette. Biophys J 75: 1553– 1572, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheung LS, Konstantopoulos K. An analytical model for determining two-dimensional receptor-ligand kinetics. Biophys J 100: 2338– 2346, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coughlin SR. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature 407: 258– 264, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eichbaum C, Meyer AS, Wang N, Bischofs E, Steinborn A, Bruckner T, Brodt P, Sohn C, Eichbaum MHR. Breast cancer cell-derived cytokines, macrophages and cell adhesion: implications for metastasis. Anticancer Res 31: 3219– 3227, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Felding-Habermann B, Habermann R, Saldivar E, Ruggeri ZM. Role of beta 3 integrins in melanoma cell adhesion to activated platelets under flow. J Biol Chem 271: 5892– 5900, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Felding-Habermann B, Ruggeri ZM, Cheresh DA. Distinct biological consequences of integrin-α-v-β-3-mediated melanoma cell-adhesion to fibrinogen and its plasmic fragments. J Biol Chem 267: 5070– 5077, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flick MJ, Du XL, Witte DP, Jirouskova M, Soloviev DA, Busuttil SJ, Plow EF, Degen JL. Leukocyte engagement of fibrin(ogen) via the integrin receptor α(M)β(2)/Mac-1 is critical for host inflammatory response in vivo. J Clin Invest 113: 1596– 1606, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fu CL, Tong CF, Dong C, Long M. Modeling of cell aggregation dynamics governed by receptor-ligand binding under shear flow. Cell Mol Bioeng 4: 427– 441, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fu CL, Tong CF, Wang ML, Gao YX, Zhang Y, Lu SQ, Liang SL, Dong C, Long M. Determining β(2)-integrin and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 binding kinetics in tumor cell adhesion to leukocytes and endothelial cells by a gas-driven micropipette assay. J Biol Chem 286: 34777– 34787, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gopalan PK, Smith CW, Lu HF, Berg EL, McIntire LV, Simon SI. Neutrophil CD18-dependent arrest on intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) in shear flow can be activated through L-selectin. J Immunol 158: 367– 375, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gunji Y, Lewis J, Gorelik E. Fibrin formation inhibits the in vitro cytotoxic activity of human natural and lymphokine-activated killer cells. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1: 663– 672, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoskins MH, Dong C. Kinetics analysis of binding between melanoma cells and neutrophils. Mol Cell Biomech 3: 79– 87, 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huh SJ, Liang S, Sharma A, Dong C, Robertson GP. Transiently entrapped circulating tumor cells interact with neutrophils to facilitate lung metastasis development. Cancer Res 70: 6071– 6082, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Im JH, Fu WL, Wang H, Bhatia SK, Hammer DA, Kowalska MA, Muschel RJ. Coagulation facilitates tumor cell spreading in the pulmonary vasculature during early metastatic colony formation. Cancer Res 64: 8613– 8619, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kong F, Garcia AJ, Mould AP, Humphries MJ, Zhu C. Demonstration of catch bonds between an integrin and its ligand. J Cell Biol 185: 1275– 1284, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Konstantopoulos K, Raman PS, Alves CS, Wirtz D. Single-molecule binding of CD44 to fibrin versus P-selectin predicts their distinct shear-dependent interactions in cancer. J Cell Sci 124: 1903– 1910, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Konstantopoulos K, Thomas SN. Cancer cells in transit: the vascular interactions of tumor cells. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 11: 177– 202, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kumar RA, Dong JF, Thaggard JA, Cruz MA, Lopez JA, McIntire LV. Kinetics of GPIb α-vWF-A1 tether bond under flow: effect of GPIb alpha mutations on the association and dissociation rates. Biophys J 85: 4099– 4109, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Languino LR, Plescia J, Duperray A, Brian AA, Plow EF, Geltosky JE, Altieri DC. Fibrinogen mediates leukocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium through an ICAM-1-dependent pathway. Cell 73: 1423– 1434, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liang S, Dong C. Integrin VLA-4 enhances sialyl-Lewis(x/a)-negative melanoma adhesion to and extravasation through the endothelium under low flow conditions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C701– C707, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liang S, Hoskins M, Khanna P, Kunz RF, Dong C. Effects of the tumor-leukocyte microenvironment on melanoma-neutrophil adhesion to the endothelium in a shear flow. Cell Mol Bioeng 1: 189– 200, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liang S, Slattery MJ, Dong C. Shear stress and shear rate differentially affect the multi-step process of leukocyte-facilitated melanoma adhesion. Exp Cell Res 310: 282– 292, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liang SL, Fu CL, Wagner D, Guo HG, Zhan DY, Dong C, Long M. Two-dimensional kinetics of β2-integrin and ICAM-1 bindings between neutrophils and melanoma cells in a shear flow. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C743– C753, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liang SL, Sharma A, Peng HH, Robertson G, Dong C. Targeting mutant (V600E) B-Raf in melanoma interrupts immunoediting of leukocyte functions and melanoma extravasation. Cancer Res 67: 5814– 5820, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Litvinov RI, Bennett JS, Weisel JW, Shuman H. Multi-step fibrinogen binding to the integrin α llb β 3 detected using force spectroscopy. Biophys J 89: 2824– 2834, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Litvinov RI, Shuman H, Bennett JS, Weisel JW. Binding strength and activation state of single fibrinogen-integrin pairs on living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 7426– 7431, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McEver RP, Zhu C. Rolling cell adhesion. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26: 363– 396, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Medved L, Yakovlev S, Li Z, Ugarova T. Interaction of fibrin(ogen) with leukocyte receptor α(M)β(2) (Mac-1): further characterization and identification of a novel binding region within the central domain of the fibrinogen gamma-module. Biochemistry 44: 617– 626, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mosesson MW. Fibrinogen gamma chain functions. J Thromb Haemost 1: 231– 238, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mueller BM, Reisfeld RA, Edgington TS, Ruf W. Expression of tissue factor by melanoma-cells promotes efficient hematogenous metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 11832– 11836, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Muller AM, Hermanns MI, Cronen C, Kirkpatrick CJ. Comparative study of adhesion molecule expression in cultured human macro- and microvascular endothelial cells. Exp Mol Pathol 73: 171– 180, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Muller B, Zerwes HG, Tangemann K, Peter J, Engel J. 2-Step binding mechanism of fibrinogen to α-IIB-β-3 integrin reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem 268: 6800– 6808, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mullin JL, Gorkun OV, Binnie CG, Lord ST. Recombinant fibrinogen studies reveal that thrombin specificity dictates order of fibrinopeptide release. J Biol Chem 275: 25239– 25246, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Munn LL, Melder RJ, Jain RK. Analysis of cell flux in the parallel-plate flow chamber–implications for cell capture studies. Biophys J 67: 889– 895, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mytar B, Siedlar M, Woloszyn M, Colizzi V, Zembala M. Cross-talk between human monocytes and cancer cells during reactive oxygen intermediates generation: the essential role of hyaluronan. Int J Cancer 94: 727– 732, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Natali PG, Hamby CV, FeldingHabermann B, Liang BT, Nicotra MR, DiFilippo F, Giannarelli D, Temponi M, Ferrone S. Clinical significance of α(v)β(3) integrin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in cutaneous malignant melanoma lesions. Cancer Res 57: 1554– 1560, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ngo B, Farrell CP, Barr M, Wolov K, Bailey R, Mullin JM, Thornton JJ. Tumor necrosis factor blockade for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: efficacy and safety. Curr Mol Pharmacol 3: 145– 152, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nierodzik ML, Plotkin A, Kajumo F, Karpatkin S. Thrombin stimulates tumor-platelet adhesion in vitro and metastasis in vivo. J Clin Invest 87: 229– 236, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Palumbo JS, Barney KA, Blevins EA, Shaw MA, Mishra A, Flick MJ, Kombrinck KW, Talmage KE, Souri M, Ichinose A, Degen JL. Factor XIII transglutaminase supports hematogenous tumor cell metastasis through a mechanism dependent on natural killer cell function. J Thromb Haemost 6: 812– 819, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Palumbo JS, Kombrinck KW, Drew AF, Grimes TS, Kiser JH, Degen JL, Bugge TH. Fibrinogen is an important determinant of the metastatic potential of circulating tumor cells. Blood 96: 3302– 3309, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Massari JV, La Jeunesse CM, Flick MJ, Kombrinck KW, Hu Z, Barney KA, Degen JL. Tumor cell-associated tissue factor and circulating hemostatic factors cooperate to increase metastatic potential through natural killer cell-dependent and-independent mechanisms. Blood 110: 133– 141, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Massari JV, La Jeunesse CM, Flick MJ, Kombrinck KW, Jirouskova M, Degen JL. Platelets and fibrin(ogen) increase metastatic potential by impeding natural killer cell-mediated elimination of tumor cells. Blood 105: 178– 185, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pantel K, Schlimok G, Angstwurm M, Passlick B, Izbicki JR, Johnson JP, Riethmuller G. Early metastasis of human solid tumours: expression of cell adhesion molecules. Ciba Found Symp 189: 157– 174, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pecheur I, Peyruchaud O, Serre CM, Guglielmi J, Voland C, Bourre F, Margue C, Cohen-Solal M, Buffet A, Kieffer N, Clezardin P. Integrin α v β 3 expression confers on tumor cells a greater propensity to metastasize to bone. FASEB J 16: 1266– 1268, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pierres A, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P. Studying molecular interactions at the single bond level with a laminar flow chamber. Cell Mol Bioeng 1: 247– 262, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pilch J, Habermann R, Felding-Habermann B. Unique ability of integrin α(v)β(3) to support tumor cell arrest under dynamic flow conditions. J Biol Chem 277: 21930– 21938, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 71– 78, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Puri KD, Chen SQ, Springer TA. Modifying the mechanical property and shear threshold of L-selectin adhesion independently of equilibrium properties. Nature 392: 930– 933, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ramachandran V, Yago T, Epperson TK, Kobzdej MMA, Nollert MU, Cummings RD, Zhu C, McEver RP. Dimerization of a selectin and its ligand stabilizes cell rolling and enhances tether strength in shear flow. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10166– 10171, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Raman PS, Alves CS, Wirtz D, Konstantopoulos K. Single-molecule binding of CD44 to fibrin versus P-selectin predicts their distinct shear-dependent interactions in cancer. J Cell Sci 124: 1903– 1910, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rickles FR, Falanga A. Molecular basis for the relationship between thrombosis and cancer. Thromb Res 102: V215– V224, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rickles FR, Patierno S, Fernandez PM. Tissue factor, thrombin, cancer. Chest 124: 58S– 68S, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rinker KD, Prabhakar V, Truskey GA. Effect of contact time and force on monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium. Biophys J 80: 1722– 1732, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schmitt M, Janicke F, Moniwa N, Chucholowski N, Pache L, Graeff H. Tumor-associated urokinase-type plasminogen-activator–biological and clinical significance. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 373: 611– 622, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shimizu A, Schindlauer G, Ferry JD. Interaction of the fibrinogen-binding tetrapeptide Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro with fine clots and oligomers of α-fibrin–comparisons with α-β-fibrin. Biopolymers 27: 775– 788, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Simon SI, Green CE. Molecular mechanics and dynamics of leukocyte recruitment during inflammation. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 7: 151– 185, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Slattery MJ, Dong C. Neutrophils influence melanoma adhesion and migration under flow conditions. Int J Cancer 106: 713– 722, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Slattery MJ, Liang S, Dong C. Distinct role of hydrodynamic shear in leukocyte-facilitated tumor cell extravasation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C831– C839, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Smith CW, Entman ML, Lane CL, Beaudet AL, Ty TI, Youker K, Hawkins HK, Anderson DC. Adherence of neutrophils to canine cardiac myocytes in vitro is dependent on intercellular-adhesion molecule-1. J Clin Invest 88: 1216– 1223, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration–the multistep paradigm. Cell 76: 301– 314, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sugama Y, Tiruppathi C, Janakidevi K, Andersen TT, Fenton JW, Malik AB. Thrombin-induced expression of endothelial P-selectin and intercellular-adhesion molecule-1-a mechanism for stabilizing neutrophil adhesion. J Cell Biol 119: 935– 944, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Taylor PR, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin HH, Brown GD, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol 23: 901– 944, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Trousseau A, Bazire PV, Cormack JR. Lectures on Clinical Medicine. London: R. Hardwicke, 1867 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vitte J, Pierres A, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P. Direct quantification of the modulation of interaction between cell- or surface-bound LFA-1 and ICAM-1. J Leukoc Biol 76: 594– 602, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wang JK, Slattery MJ, Hoskins MH, Liang SL, Dong C, Du Q. Monte Carlo simulation of heterotypic cell aggregation in nonlinear shear flow. Math Biosci Eng 3: 683– 696, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wislez M, Rabbe N, Marchal J, Milleron B, Crestani B, Mayaud C, Antoine M, Soler P, Cadranel J. Hepatocyte growth factor production by neutrophils infiltrating bronchioloalveolar subtype pulmonary adenocarcinoma: role in tumor progression and death. Cancer Res 63: 1405– 1412, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yokoyama K, Erickson HP, Ikeda Y, Takada Y. Identification of amino acid sequences in fibrinogen γ-chain and tenascin CC-terminal domains critical for binding to integrin α(v)β(3). J Biol Chem 275: 16891– 16898, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhang F, Marcus WD, Goyal NH, Selvaraj P, Springer TA, Zhu C. Two-dimensional kinetics regulation of α(L)β(2)-ICAM-1 interaction by conformational changes of the α(L)-inserted domain. J Biol Chem 280: 42207– 42218, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhang P, Ozdemir T, Chung CY, Robertson GP, Dong C. Sequential binding of α(v)β(3) and ICAM-1 determines fibrin-mediated melanoma capture and stable adhesion to CD11b/CD18 on neutrophils. J Immunol 186: 242– 254, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zimmerman GA, Mcintyre TM, Prescott SM. Thrombin stimulates the adherence of neutrophils to human-endothelial cells-in vitro. J Clin Invest 76: 2235– 2246, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]