Abstract

This study was conducted to examine the relationship between the peroxisome proliferator-associated receptor-γ (PPARγ) and MUC1 mucin, two anti-inflammatory molecules expressed in the airways. Treatment of A549 lung epithelial cells or primary mouse tracheal surface epithelial (MTSE) cells with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) increased the levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in cell culture media compared with cells treated with vehicle alone. Overexpression of MUC1 in A549 cells decreased PMA-stimulated TNF-α levels, whereas deficiency of Muc1 expression in MTSE cells from Muc1 null mice increased PMA-induced TNF-α levels. Treatment of A549 or MTSE cells with the PPARγ agonist troglitazone (TGN) blocked the ability of PMA to stimulate TNF-α levels. However, the effect of TGN required the presence of MUC1/Muc1, since no differences in TNF-α levels were seen between PMA and PMA plus TGN in MUC1/Muc1-deficient cells. Similarly, whereas TGN decreased interleukin-8 (IL-8) levels in culture media of MUC1-expressing A549 cells treated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain K (PAK), no differences in IL-8 levels were seen between PAK and PAK plus TGN in MUC1-nonexpressing cells. EMSA confirmed the presence of a PPARγ-binding element in the MUC1 gene promoter. Finally, TGN treatment of A549 cells increased MUC1 promoter activity measured using a MUC1-luciferase reporter gene, augmented MUC1 mRNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR, and enhanced MUC1 protein expression by Western blot analysis. These combined data are consistent with the hypothesis that PPARγ stimulates MUC1/Muc1 expression, thereby blocking PMA/PAK-induced TNF-α/IL-8 production by airway epithelial cells.

Keywords: lung, peroxisome proliferator-associated receptor-γ, PMA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

exposed to more than 10,000 liters of air each day, the human respiratory tract constitutes a major interface with the external environment. An acute inflammatory response is mounted in the airways following exposure to airborne pathogens. While respiratory inflammatory responses restrain colonization by microbial pathogens, they must also be tightly regulated to maintain normal lung function. In this regard, a diverse and growing repertoire of molecules have been shown to suppress airway inflammation (13, 18, 35, 43, 50, 54, 62), including the peroxisome proliferator-associated receptor-γ (PPARγ; Refs. 5, 11, 57) and MUC1 (25, 36, 40, 55). For review, see Refs. 7, 15, 51. Why so many anti-inflammatory molecules exist in the airways, and whether they interact among themselves or with other as yet unidentified molecules, remain to be determined.

PPARs comprise a family of nuclear receptors that function as transcription factors to regulate gene expression (4, 27). Following ligand engagement, PPARs translocate to the nucleus, heterodimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXRs), and the PPAR/RXR complexes bind to PPAR response elements in gene promoters. Depending on the target gene(s) affected, PPARs regulate a variety of cellular processes, including differentiation, development, metabolism, tumorigenesis, and inflammation. In the latter case, PPARs control the expression of inflammatory genes by negative interference with NF-κB, activating protein-1, stimulating protein 1 (Sp1), and signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (6).

Three subtypes of PPARs are known, PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ. PPARγ is expressed as two isoforms, PPARγ1 and PPARγ2, that differ by the presence of a unique 30 amino acid segment in the latter (14). PPARγ2 is primarily expressed in adipose tissue, while PPARγ1 is expressed in the lung, heart, skeletal muscle, intestine, kidney, pancreas, spleen, breast, and lymphoid tissues (56). Both PPARγ molecules are activated by prostanoids, a subclass of eicosanoids consisting of prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and prostacyclins. Synthetic PPARγ ligands, such as the thiazolidinediones (TZDs or glitazones; Ref. 16), have been developed that suppress inflammation both in vitro and in vivo (4, 35, 57, 58), including the airway inflammatory response following lung infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (46). However, the mechanisms by which PPARγ downregulates inflammation are not completely understood.

MUC1 (MUC1 in human, Muc1 in animals) is a membrane-tethered, heterodimeric glycoprotein expressed on the apical surface of most simple mucosal epithelia, as well as the surface of hematopoietic cells (45). Our previous studies (32, 36, 40) showed that MUC1/Muc1 plays an important anti-inflammatory role during airway infection by bacterial and viral pathogens. In particular, Muc1−/− mice responded to P. aeruginosa infection with higher levels of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid cytokines and chemokines and greater numbers of BAL fluid inflammatory cells, coincident with increased bacterial clearance from the lungs, compared with Muc1+/+ littermates (40). In vivo and in vitro mechanistic studies in human and mouse model systems revealed that an initial increase in TNF-α levels early during the course of P. aeruginosa lung infection upregulated MUC1/Muc1 expression, which, in turn, suppressed Toll-like receptor-5 signaling and downstream inflammatory responses (8, 28). In effect, MUC1/Muc1 acts through a feed-back loop mechanism in an anti-inflammatory manner during airway infection by microbial and viral pathogens (for review, see Ref. 25). Interestingly, the MUC1/Muc1 gene promoters contain a putative PPARγ-binding site, and ligand-induced activation of PPARγ was reported to increase Muc1 mRNA levels in a mouse trophoblast cell line (52). Therefore, in this study we asked whether the anti-inflammatory effect of PPARγ is mediated through the expression of MUC1/Muc1 in airway epithelial cells. The anti-inflammatory effect of PPARγ agonists has been extensively demonstrated in various cell culture systems. In the present study, we employed a well-established in vitro model in which PPARγ has been shown to inhibit PMA-induced production of inflammatory cytokines (23).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All materials were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

Cell culture.

A549 cells, a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (CCL-185, ATCC, Manassas, VA), were seeded in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) in 24-well plates at 5.0 × 104 cells/well and cultured overnight to confluence at 37°C in 5% CO2. Primary mouse tracheal surface epithelial (MTSE) cells were isolated by pronase digestion of whole trachea from male FVB mice at 10–15 wk of age and cultured on a thick collagen gel in 24-well plates at 37°C in 5% CO2 as described previously (41). All protocols were approved by the Temple University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and troglitazone treatments.

A549 or MTSE cells in 24-well plates were washed with PBS and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 1.0 μM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), or with DMSO vehicle control, in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% FBS (A549 cells) or in DME/F-12 medium containing 5.0 μg/ml insulin, 5.0 μg/ml transferrin, 12.5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 10−7 M hydrocortisone, 10−7 M retinoic acid, 10−7 M sodium selenite, 0.2% bovine pituitary extract, and 5.0% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT; MTSE cells). The cells were pretreated for 1 h with 1.0 μM troglitazone (TGN) or DMSO vehicle control before incubation for 24 h with PMA.

P. aeruginosa treatment.

P. aeruginosa strain K (PAK) was cultured in Luria broth at 37°C for 16 h, and an aliquot of the bacterial culture was cultured for an additional 2 h to produce bacteria in log phase. The PAK culture was centrifuged for 10 min at 600 g, heat killed at 60°C for 1 h, and resuspended in sterile PBS. A549 cells in 24-well plates were washed with PBS, pretreated for 1 h with 1.0 μM TGN or DMSO vehicle control, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 1.0 × 108 colony-forming units of heat-killed PAK, or with PBS vehicle control, in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% FBS.

TNF-α and IL-8 ELISA.

ELISAs for mouse and human TNF-α and human IL-8 in cell culture supernatants were performed as described previously (28) using appropriate capture and detection antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and standard curves were performed on each plate.

Transient transfection and luciferase assay.

A549 cells at 90–95% confluence in 24-well plates were transfected with plasmid DNAs or small interfering (si)RNAs (17) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Plasmid DNA samples were 800 ng/well of a full-length MUC1 cDNA (38), or the pcDNA3.1 empty vector control, or a MUC1 promoter-firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (MUC1-pGL2b; Ref. 30), or the empty pGL2b vector control, plus 10 ng/well of phRL-TK internal control plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI). In cells transfected with MUC1-pGL2b or pGL2b empty vector, luciferase activity was determined using the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and a microplate luminometer (Lmax; Molecular Devices) as described previously (28).

MUC1 immunoblotting.

A549 and MTSE cells were lysed with PBS pH 7.2, 1.0% NP-40, 1.0% sodium deoxycholate, and 1.0% protease inhibitor cocktail. Equal protein aliquots were resolved on 15% SDS-acrylamide gels and analyzed by immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody CT2 against the MUC1 cytoplasmic tail as described previously (28). To control for protein loading and transfer, blots were stripped and reprobed with antibody against β-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

EMSA.

A549 cells were untransfected or were transiently transfected as described above with expression plasmids encoding human PPARγ and/or RXRα (generous gifts of Dr. Mitchell A. Lazar, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) or with the pcDNA3.1 empty vector. The cells were incubated for 24 h with 0.1, 1.0, or 10 μM TGN or with DMSO vehicle control, and nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (30). Briefly, cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS containing 1.0 mM PMSF, and lysed with 10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.8, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.25% Igepal CA-630, 1.0 mM PMSF, and 1.0% protease inhibitor cocktail on ice for 10 min. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation (1 min at 1,250 g at 4°C) and lysed in 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.8, 25% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM DTT, 1.0 mM PMSF, and 1.0% protease inhibitor cocktail for 30 min on ice. The nuclear lysate was centrifuged at 13,200 g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.8, 20% glycerol, 50 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM DTT, 1.0 mM PMSF, and 1.0% protease inhibitor cocktail for 2 h at 4°C. Protein concentrations were measured as described above. Nuclear extracts (2.0 or 10 μg) were incubated for 20 min at room temperature with 25 fmol of a biotinylated oligonucleotide probe identical in sequence to nucleotides −93 to −66 of the MUC1 promoter (5′-GAGTTTTGTCACCTGTCACCTGCTCCGG-3′) and corresponding to the antisense strand of the putative PPARγ-binding element (underlined sequence). Addition of 100-fold molar excesses of the unlabeled probe of identical sequence, or a probe with identical nucleotide composition but scrambled sequence, was used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Incubation buffer was 20 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM KCl, 5.0 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 62.5% glycerol. In some experiments, nuclear extracts were incubated in the presence of 1.0 μg of a human PPARγ-neutralizing antibody (Santa Cruz) to remove PPARγ protein. The DNA-protein complexes were resolved on 5.0% polyacrylamide gels in 89 mM Tris base, 89 mM boric acid, and 2.0 mM EDTA, blotted to PVDF membranes, probed with streptavidin-labeled horseradish peroxidase and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, and visualized as described above.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

A549 cells were treated for 24 h with 0 (DMSO vehicle control), 0.1, or 1.0 μM TGN, total RNA was isolated using the Mini RNA Isolation II kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA), and quantitative RT-PCR for MUC1 or GAPDH internal control mRNAs was performed as described previously (28). The levels of MUC1 transcripts were normalized to GAPDH transcripts, and the normalized levels in TGN-treated cells were compared with those of DMSO-treated cells using the 2−ΔΔCt method (28).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey's range test for post hoc multiple comparisons. A significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

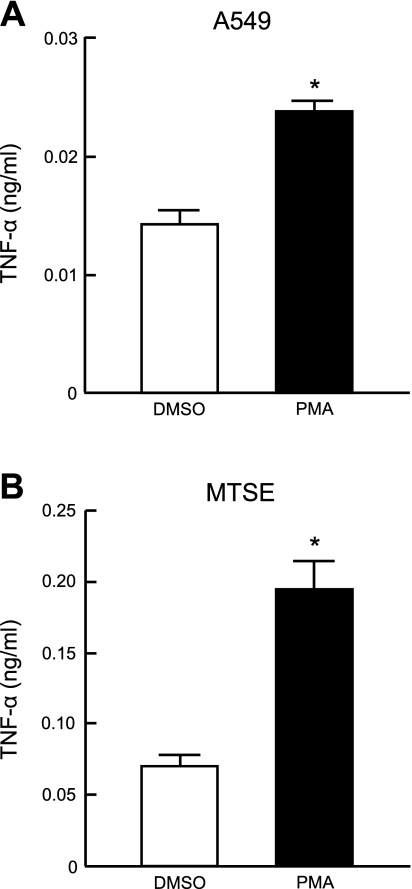

PMA stimulates TNF-α production by airway epithelial cells.

PMA is reported to elicit a proinflammatory response in the 1HAEo− human tracheobronchial epithelial cell line (22), but the effect of this phorbol ester on primary airway epithelial cells or downstream cytokine production is less clear. Therefore, primary MTSE and A549 cells were treated with 1.0 μM PMA, or with the DMSO vehicle control, for 24 h, and TNF-α levels in cell culture media were measured by ELISA. In the case of MTSE cells, retinoic acid was removed from the culture medium at 80% confluence since retinoic acid has been shown to inhibit the effect of PMA (9, 24). As shown in Fig. 1, PMA treatment increased TNF-α levels in both cell types compared with DMSO treatment.

Fig. 1.

PMA stimulates TNF-α production by airway epithelial cells. A549 (A) and primary mouse tracheal surface epithelial (MTSE; B) cells were incubated for 24 h with 1.0 μM PMA or with DMSO vehicle control, and TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Each bar represents means ± SE value (n = 3). *P < 0.05. Results were reproducible in a separate experiment.

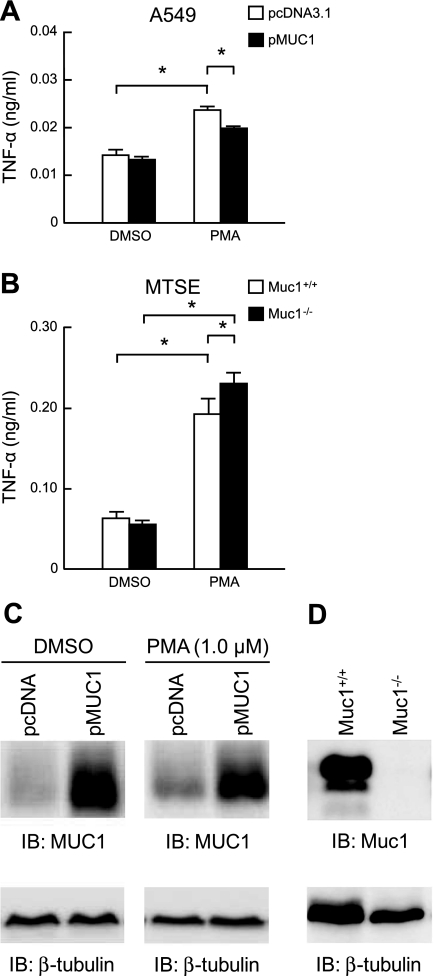

Manipulation of MUC1 expression inversely correlates with PMA-induced TNF-α production.

Alteration of MUC1 expression, either by in vitro MUC1 plasmid transfection of HEK293T cells or by in vivo genetic deletion in Muc1−/− mice, inversely correlates with TNF-α production in response to inflammatory stimuli (55). Therefore, we sought to determine whether MUC1/Muc1 expression affected PMA-stimulated TNF-α levels in airway epithelial cells. A549 cells overexpressing MUC1 had moderately, but statistically significant, reduced levels of TNF-α following treatment with 1.0 μM PMA for 24 h, compared with PMA-treated cells transfected with the empty vector control (Fig. 2A). Conversely, primary MTSE cells from Muc1−/− mice had increased PMA-stimulated TNF-α levels, compared with Muc1+/+ MTSE cells (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis confirmed ectopic MUC1 overexpression and Muc1 deletion in the respective cells (Figs. 2, C and D). Further, PMA treatment of MUC1-transfected A549 cells did not affect MUC1 expression (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Manipulation of MUC1 expression inversely correlates with PMA-induced TNF-α production. A: A549 cells were transiently transfected with a pMUC1 expression plasmid or the pcDNA3.1 empty vector negative control. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were incubated for 24 h with 1.0 μM PMA or with DMSO vehicle control, and TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. B: primary MTSE cells from Muc1+/+ or Muc1−/− mice were incubated for 24 h with 1.0 μM PMA or with DMSO vehicle control, and TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. In A and B, each bar represents means ± SE value (n = 3). *P < 0.05. C: lysates of DMSO- or PMA-treated A549 cells transfected with the pcDNA3.1 or pMUC1 plasmids were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-MUC1 cytoplasmic tail antibody. D: lysates of MTSE cells from Muc1+/+ and Muc1−/− mice were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 cytoplasmic tail antibody. In C and D, to control for protein loading and transfer, blots were stripped and reprobed for β-tubulin. Results were reproducible in a separate experiment.

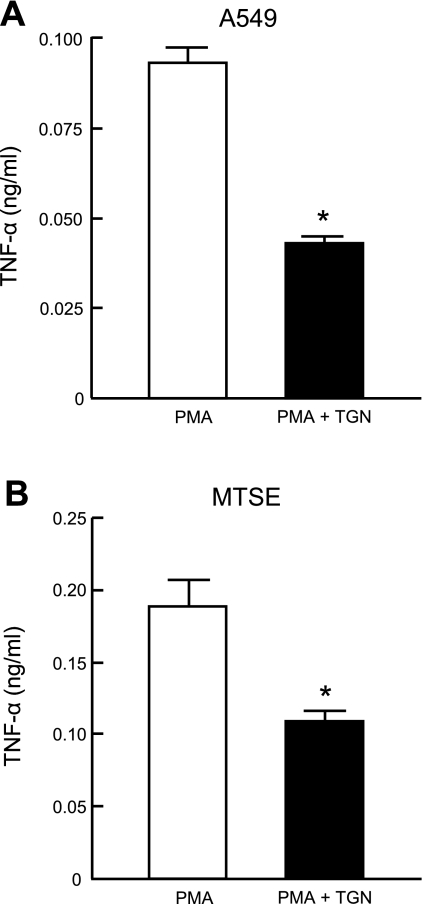

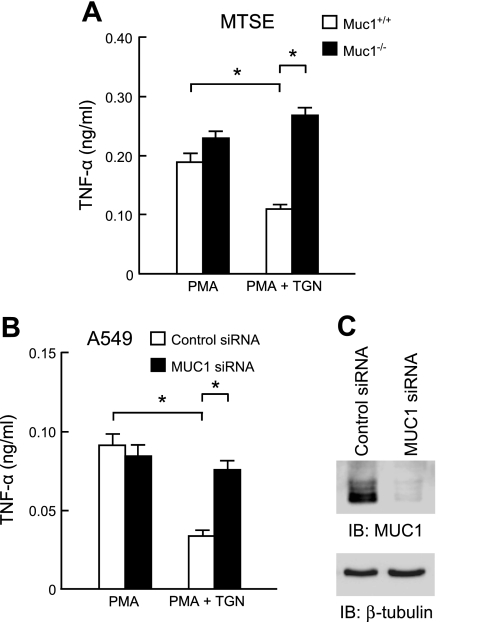

TGN inhibits PMA-stimulated TNF-α production by airway epithelial cells through MUC1/Muc1.

PPARγ plays an important regulatory role in airway inflammatory responses (48, 49). Therefore, we asked whether activation of PPARγ in A549 and/or MTSE cells influenced PMA-induced TNF-α levels and, if so, what was the role of MUC1/Muc1 in this response. A549 and MTSE cells pretreated for 1 h with the PPARγ agonist, TGN (1.0 μM) before PMA treatment had reduced levels of TNF-α in culture media, compared with cells treated with PMA alone (Fig. 3). In contrast, TNF-α levels were equal in Muc1−/− MTSE cells treated with PMA alone or with PMA plus TGN (Fig. 4A). The viability of Muc1+/+ and Muc1−/− MTSE cells was unaffected by either of the treatment protocols (data not shown). As a confirmatory approach, A549 cells were transiently transfected with a MUC1-targeting siRNA, or a nontargeting negative control siRNA, and TNF-α levels were measured in culture supernatants following treatment with PMA alone or with PMA plus TGN. As shown in Fig. 4B, while TNF-α levels were decreased in control siRNA-transfected cells treated with PMA plus TGN, compared with PMA alone, the levels of the cytokine were equal in MUC1 siRNA-transfected cells treated with PMA alone or with PMA plus TGN. Western blot analysis verified >90% MUC1 protein knockdown in MUC1 siRNA-transfected A549 cells (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 3.

Troglitazone (TGN) inhibits PMA-stimulated TNF-α production by airway epithelial cells. A549 (A) and primary MTSE (B) cells were incubated for 1 h with 1.0 μM TGN or with DMSO vehicle control. Cells were washed and incubated for 24 h with 1.0 μM PMA, and TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Each bar represents means ± SE value (n = 3). *P < 0.05. Results were reproducible in a separate experiment.

Fig. 4.

TGN inhibits PMA-stimulated TNF-α production by airway epithelial cells through MUC1/Muc1. A: primary MTSE cells from Muc1+/+ or Muc1−/− mice were pretreated for 1 h with 1.0 μM TGN or with DMSO vehicle control and incubated for 24 h with 1.0 μM PMA, and TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. B: A549 cells were transiently transfected with a MUC1-targeting siRNA, or a nontargeting small interfering (si)RNA negative control. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were pretreated for 1 h with 1.0 μM TGN or with DMSO vehicle control and incubated for 24 h with 1.0 μM PMA, and TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. In A and B, each bar represents means ± SE value (n = 3). *P < 0.05. C: lysates of PMA plus TGN-treated or PMA only-treated A549 cells transfected with the control or MUC1 siRNAs were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 cytoplasmic tail antibody. To control for protein loading and transfer, blots were stripped and reprobed for β-tubulin. Results were reproducible in a separate experiment.

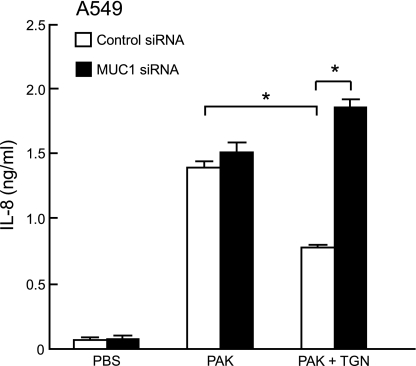

TGN inhibits P. aeruginosa-stimulated IL-8 production by A549 cells through MUC1.

To determine the role of PPARγ in P. aeruginosa-stimulated IL-8 production, A549 cells were transfected with the MUC1 siRNA or negative control siRNA, pretreated for 1 h with 1.0 μM TGN or DMSO vehicle control, and treated for 24 h with PAK or PBS control, and IL-8 levels in culture media were measured by ELISA. While IL-8 levels were decreased in control siRNA-transfected cells treated with PAK plus TGN, compared with PAK alone, the levels of the cytokine were equal in MUC1 siRNA-transfected cells treated with PAK alone or with PAK plus TGN (Fig. 5). Of note, in this experiment knockdown of MUC1 expression had little effect on PAK-induced IL-8 levels in the absence of TGN due to the relatively longer time of bacterial treatment required for increased MUC1 expression (maximum levels at 48 h posttreatment; Ref. 8). On the other hand, TGN induced MUC1 within 8 h (see Fig. 7E) and the increased MUC1 at the time of PAK treatment suppressed PAK-induced IL-8 release. In summary, the results in Figs. 3–5 suggest that activation of PPARγ by TGN reduces PMA-stimulated TNF-α production and PAK-stimulated IL-8 production by airway epithelial cells through a MUC1/Muc1-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 5.

A549 cells were transiently transfected with a MUC1-targeting siRNA or a nontargeting siRNA negative control. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were pretreated for 1 h with 1.0 μM TGN or DMSO vehicle control, incubated for 24 h with 1.0 × 108 colony-forming units heat-killed PAK or PBS vehicle control, and IL-8 levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Each bar represents means ± SE value (n = 3). *P < 0.05. Results were reproducible in a separate experiment.

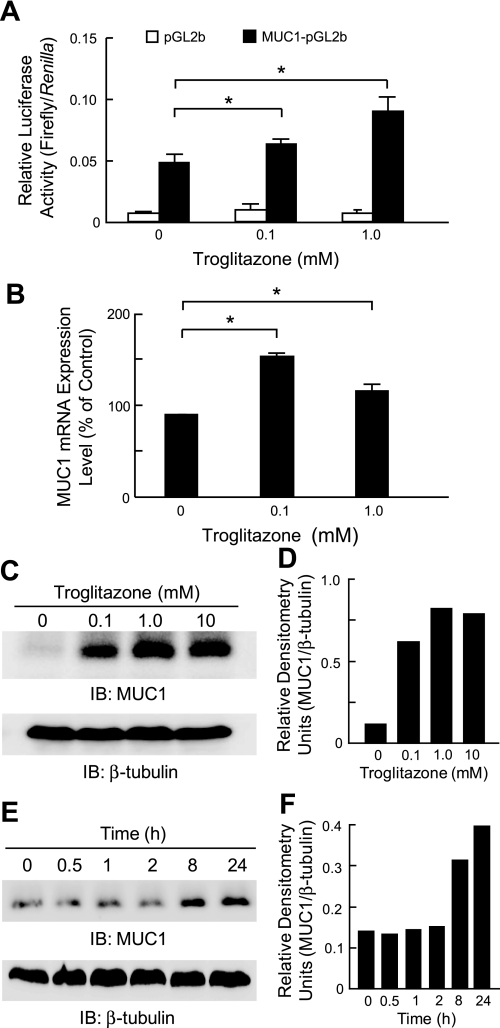

Fig. 7.

Troglitazone stimulates MUC1 expression through PPARγ. A: A549 cells were transiently transfected with a MUC1 promoter-luciferase reporter gene (MUC1-pGL2b) or with the empty pGL2b vector as a negative control, plus the phRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid internal control. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were incubated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of TGN or with DMSO vehicle control, and relative luciferase activity of cell lysates was measured. B: A549 cells were incubated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of TGN, or with DMSO vehicle control, and MUC1 mRNA levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels. In A and B, each bar represents means ± SE value (n = 3). *P < 0.05. Results were reproducible in a separate experiment. C: A549 cells were incubated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of TGN or with DMSO vehicle control, and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 cytoplasmic tail antibody. To control for protein loading and transfer, blot was stripped and reprobed for β-tubulin. D: densitometric analysis of the MUC1 bands in the blot in C normalized to the respective β-tubulin bands. Results represent 2 independent experiments. E: A549 cells were incubated for the indicated times with 1.0 μM TGN and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 cytoplasmic tail antibody. To control for protein loading and transfer, blot was stripped and reprobed for β-tubulin. F: densitometric analysis of the MUC1 bands in the blot in E normalized to the respective β-tubulin bands.

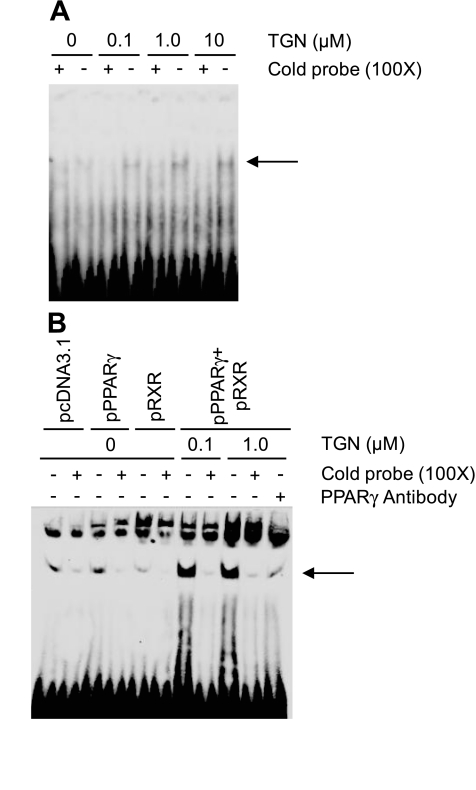

TGN increases PPARγ-binding to the MUC1 gene promoter.

The mouse Muc1 gene promoter contains a putative PPARγ response element, and PPARγ increased Muc1 mRNA levels in mouse trophoblast stem cells (52). To identify the relationship, if any, between human MUC1 and PPARγ, we first analyzed the 5′-flanking region of the human MUC1 gene. A potential PPARγ-binding element in the MUC1 promoter, 5′-AGGTGACAGGTGA-3′, was identified between nucleotides −84 and −73 relative to the transcription start site based on homology with the mouse sequence. This element is 84.6% identical to the PPAR-binding consensus sequence, 5′-AGGTCANAGGTCA-3′ (N, any nucleotide; identical nucleotides underlined; Ref. 52). Two approaches were used to determine whether PPARγ binds to this potential binding element in airway epithelial cells. First, A549 cells were incubated for 24 h with various concentrations of TGN or with DMSO control, and nuclear extracts were probed by EMSA with a synthetic oligonucleotide corresponding to the MUC1 promoter sequence between nucleotides −93 to −66 and covering the putative PPARγ-binding element. TGN-treated cells contained an oligonucleotide-binding band that was not present in the extracts of DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 6A, arrow). The intensity of this band increased with increasing concentrations of TGN. Moreover, its intensity was substantially reduced in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of the unlabeled (cold) oligonucleotide with an identical DNA sequence but not by a negative control oligonucleotide with identical DNA composition but a scrambled probe sequence. In the second approach, A549 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids encoding the PPARγ and/or RXRα transcription factors or the pcDNA3.1 empty vector control, the cells were treated with TGN or with DMSO control, and nuclear extracts were probed with the oligonucleotide corresponding to the potential PPARγ-binding element in the MUC1 promoter. Cotransfection with PPARγ plus PXR followed by incubation with 0.1 or 1.0 μM TGN dramatically increased the intensity of the oligonucleotide-binding band, compared with DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 6B, arrow). The intensity of this band was decreased in the presence of an excess of the unlabeled oligonucleotide but not by the negative control oligonucleotide with a scrambled sequence. Further, the intensity of the oligonucleotide-binding band was noticeably reduced by incubation of the nuclear extract with a PPARγ-neutralizing antibody. Taken together, these data suggest that PPARγ is a TGN-inducible protein in the nuclear extract of A549 cells that specifically binds to the presumed PPARγ-binding site in the MUC1 promoter.

Fig. 6.

TGN increases peroxisome proliferator-associated receptor-γ (PPARγ) binding to the MUC1 gene promoter. A: A549 cells were incubated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of TGN or with DMSO vehicle control. Cells were lysed and nuclear extracts (2.0 μg) were incubated for 20 min with 25 fmol of a biotinylated oligonucleotide probe identical in sequence to nucleotides −93 to −66 of the MUC1 promoter and corresponding to the putative PPARγ binding element in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of the unlabeled oligonucleotide of identical sequence to the labeled probe (+), or in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of an unlabeled oligonucleotide with identical nucleotide composition but scrambled probe sequence (−). DNA-protein complexes were resolved on a 5.0% polyacrylamide gel, blotted to PVDF membrane, probed with streptavidin-labeled horseradish peroxidase, and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, and visualized using a LAS-3000 imaging system. Arrow indicates the position of the labeled probe binding to the PPARγ/retinoid X receptor-α (RXRα) protein complex. B: A549 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids encoding human PPARγ and/or human RXRα or with the pcDNA3.1 empty vector. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of TGN, or with DMSO vehicle control. Cells were lysed and nuclear extracts (10 μg) were incubated with the biotinylated oligonucleotide probe in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of the unlabeled oligonucleotide of identical sequence (+) or an oligonucleotide with identical nucleotide composition but scrambled probe sequence (−). Other nuclear extracts were incubated in the presence of 1.0 μg of an antibody against human PPARγ. DNA-protein complexes were analyzed as above. Arrow indicates the position of the labeled probe binding to the PPARγ/RXRα protein complex.

TGN stimulates MUC1 expression through PPARγ.

Finally, to establish whether TGN alters MUC1 promoter activity, A549 cells were transiently transfected with a MUC1 promoter-luciferase reporter gene (MUC1-pGL2b) or the empty pGL2b vector as a negative control, incubated for 24 h with TGN, or DMSO vehicle control, and relative luciferase activity was measured. As shown in Fig. 7A, TGN treatment dose dependently increased luciferase activity in the MUC1-pGL2b-transfected cells, but not in pGL2b-transfected cells, compared with the DMSO control. Similarly, TGN treatment of A549 cells increased the levels of MUC1 transcripts compared with DMSO-treated cells, although in this case the effect of 0.1 μM of the PPARγ agonist was greater than that of 1.0 μM (Fig. 7B). Finally, TGN treatment increased MUC1 protein levels in both dose- and time-dependent manners (Fig. 7, C–F).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that 1) PMA stimulates TNF-α production by A549 and primary MTSE cells, 2) manipulation of human or mouse MUC1/Muc1 expression inversely correlates with PMA-stimulated TNF-α levels in cell culture media, 3) the PPARγ agonist TGN inhibits PMA-induced TNF-α levels as well as PAK-induced IL-8 levels, 4) a functional PPARγ-binding site exits in the MUC1 promoter, and 5) TGN stimulates the expression of MUC1 transcriptionally and translationally. While the effects of MUC1 overexpression (Fig. 2A) and Muc1 gene mutations (Fig. 2B) on PMA-stimulated TNF-α levels were modest, the observed differences were statistically significant and reproducible. Since TGN induces MUC1 and its anti-inflammatory effect (suppression of PMA-induced TNF-α release) was completely abrogated in MUC1-deficient cells, the relatively mild effects of MUC1 appear to be due to insufficient levels of MUC1 (Fig. 2A) and near-maximal stimulation by PMA (Fig. 2B). By comparison, the requirement for MUC1/Muc1 in the ability of TGN to suppress PMA/PAK-stimulated TNF-α/IL-8 levels in both MTSE cells and A549 cells (Figs. 4 and 5) suggests a link between the MUC1/Muc1- and PPARγ-signaling pathways. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating a functional relationship between PPARγ and MUC1, two anti-inflammatory molecules expressed in the lung.

PMA is a potent tumor promoter that activates PKC in multiple cell types (39). A review of the literature reveals evidence to suggest that PMA induces proinflammatory cytokine production by A549 and BEAS-2B airway epithelial cells through a PKC/NF-κB-dependent mechanism (1, 2, 21). Given that PPARγ negatively regulates inflammation by blocking the action of inflammatory transcription factors, including NF-κB (12), we hypothesize that PPARγ antagonizes PMA-induced TNF-α production by inhibiting NF-κB. The demonstration of a PPARγ-binding element in the human and mouse MUC1/Muc1 promoters, both in this and a previous report (52), further suggests that PPARγ may indirectly block NF-κB through MUC1/Muc1. In agreement with this proposition, increased expression of MUC1 in epithelial cells diminishes NF-κB activation (17). Further support for a relationship between PPARγ and MUC1 comes from the observed stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity, increased MUC1 mRNA levels, and enhanced MUC1 protein levels by TGN, compared with the DMSO control, although the observed TGN-MUC1 dose response suggests a complex effect. The fact that MUC1 transcript levels were decreased with 1.0 μM TGN, while MUC1 promoter activity and protein levels were increased at this concentration, compared with the 0.1 μM dose, suggests a possible effect of TGN on MUC1 mRNA and/or protein stability. It is possible that TGN activates MUC1 gene transcription while simultaneously increasing MUC1 mRNA turnover, decreasing MUC1 protein degradation, or both, in a dose-dependent manner. While our previous studies (30) demonstrated that another mucin-stimulating agonist, neutrophil elastase, increased MUC1 expression without affecting mRNA or protein turnover, TGN has been reported to alter the stability of nonmucin transcripts (3, 42, 60, 61). Ongoing studies in our laboratory are designed to test these hypotheses.

The PPARγ response element is highly conserved among species and up- or downregulates a variety of genes depending on cell type. The presence of a putative PPARγ response element in the MUC1 promoter was first suggested by Kovarik et al. (29) in which an E-box, referred to as E-MUC1 and located between nucleotides −84 and −64 relative to the ATG start site, was shown by mutational analysis to play a critical role in MUC1 transcription in ZR-75 (breast) and HPAF (pancreatic) cancer cell lines. Subsequently, the E-MUC1 sequence was shown to be identical to a functional PPARγ response element (52). In cultured human airway epithelial cells, PPARγ activation suppressed the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-8, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (44). In an ovalbumin sensitization and challenge murine model, PPARγ synthetic ligands, TZDs, attenuated the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and decreased the number of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid (23, 26). These results coincide with our previous report (40) that, compared with Muc1+/+ mice, Muc1−/− mice had increased levels of TNF-α and keratinocyte-derived chemokine, as well as greater numbers of infiltrating neutrophils in BAL fluid following experimental P. aeruginosa lung infection. Additionally, in human airway epithelial cells, knockdown of MUC1 expression by RNA interference resulted in a greater increase in TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants following respiratory syncytial virus infection, compared with control siRNA treatment (36). Together, these combined data suggest a functional relationship among PPARγ and MUC1 as anti-inflammatory molecules in the airways that is further supported by the results of the current investigation. Additional studies will be required to delineate the relationship, if any, between PPARγ, MUC1, and any of the other anti-inflammatory components that have been documented to operate in the airways, such as lipoxin A (7), resolvin (18), IL-10 (43), aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase (54), and prostacyclin (62).

The identification of a MUC1 transcriptional mechanism induced by PPARγ corroborates and extends prior work that revealed that the MUC1 promoter, in addition to a PPARγ responsive element, contains 5 putative NF-κB and 10 potential Sp1-binding sites (28). Several of these sites have been shown to mediate the response of normal and cancer epithelial cells to various inflammatory stimuli. Lagow and Carson (33) reported that combined treatment of T47D human breast cancer cells and normal human mammary epithelial cells with IFN-γ and TNF-α induced MUC1 transcription through binding of NF-κB to the MUC1 promoter at a potential NF-κB site at nucleotides −589 to −581. Binding of Sp1 to the MUC1 promoter at a −99/−90 site was involved in neutrophil elastase- and TNF-α-stimulated MUC1 expression in human airway epithelial cells (28, 30, 31). Finally, our previous studies (34) identified a positive regulatory element, located between nucleotides −555 and −252, as well as a negative regulatory element, between nucleotides −1,652 and −1,615, of the hamster Muc1 5′-untranslated region. By EMSA analysis, the yin yang 1 (YY1) transcription factor was shown to bind to the Muc1 putative negative element. A subsequent report (19), however, demonstrated that whereas overexpression of YY1 upregulated the transcriptional activity of the Muc1 promoter, deletion of the negative element did not abrogate this YY1-dependent activity. Nonetheless, it can be suggested that the presence of multiple, functionally active transcriptional elements (positive and negative) in the MUC1 promoter imparts a complex and tightly controlled regulation of MUC1 gene expression, depending on such factors as cell type, stimulatory conditions, and the presence/absence of transcriptional coactivators or corepressors. The results of the current study now add another level of complexity to this subject.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Y.S.P. and K.K. performed experiments; Y.S.P. analyzed data; Y.S.P. and E.P.L. prepared figures; Y.S.P. and E.P.L. drafted manuscript; Y.S.P., E.P.L., K.K., C.S.P., and K.C.K. approved final version of manuscript; E.P.L., K.K., C.S.P., and K.C.K. edited and revised manuscript; C.S.P. and K.C.K. conceived and designed research; K.C.K. interpreted results of experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants HL-47125 and HL-81825.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aksoy MO, Bin W, Yang Y, Yun-You D, Kelsen SG. Nuclear factor-κB augments β2-adrenergic receptor expression in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1271– L1278, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnold R, Rihoux J, König W. Cetirizine counter-regulates interleukin-8 release from human epithelial cells (A549). Clin Exp Allergy 29: 1681– 1691, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baek SJ, Wilson LC, Hsi LC, Eling TE. Troglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) ligand, selectively induces the early growth response-1 gene independently of PPARγ. A novel mechanism for its anti-tumorigenic activity. J Biol Chem 278: 5845– 5853, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belvisi MG, Hele DJ, Birrell MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists as therapy for chronic airway inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol 533: 101– 109, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belvisi MG, Mitchell JA. Targeting PPAR receptors in the airway for the treatment of inflammatory lung disease. Br J Pharmacol 158: 994– 1003, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blanquart C, Barbier O, Fruchart JC, Staels B, Glineur C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: regulation of transcriptional activities and roles in inflammation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 85: 267– 273, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carlo T, Levy BD. Chemical mediators and the resolution of airway inflammation. Allergol Int 57: 299– 305, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choi S, Park YS, Koga T, Treloar A, Kim KC. TNF-α is a key regulator of MUC1, an anti-inflammatory molecule, during airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 44: 255– 260, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarke N, Germain P, Altucci L, Gronemeyer H. Retinoids: Potential in cancer prevention and therapy. Expert Rev Mol Med 6: 1– 23, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Croce MV, Isla-Larrain M, Remes-Lenicov F, Colussi AG, Lacunza E, Kim KC, Gendler SJ, Segal-Eiras A. MUC1 cytoplasmic tail detection using CT33 polyclonal and CT2 monoclonal antibodies in breast and colorectal tissue. Histol Histopathol 21: 849– 855, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daynes RA, Jones DC. Emerging roles of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2: 748– 759, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delerive P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in inflammation control. J Endocrinol 169: 453– 459, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dolinay T, Szilasi M, Liu M, Choi AM. Inhaled carbon monoxide confers antiinflammatory effects against ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 613– 620, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspe E, Schoonjans K, Lefebvre AM, Saladin R, Najib J, Laville M, Fruchart JC, Deeb S, Vidal-Puig A, Flier J, Briggs MR, Staels B, Vidal H, Auwerx J. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARγ gene. J Biol Chem 272: 18779– 18789, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fitzgerald MF, Fox JC. Emerging trends in the therapy of COPD: novel anti-inflammatory agents in clinical development. Drug Discov Today 12: 479– 486, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giaginis C, Giagini A, Theocharis S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) ligands as potential therapeutic agents to treat arthritis. Pharmacol Res 60: 160– 169, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guang W, Ding H, Czinn SJ, Kim KC, Blanchard TG, Lillehoj EP. Muc1 cell surface mucin attenuates epithelial inflammation in response to a common mucosal pathogen. J Biol Chem 285: 20547– 20557, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haworth O, Levy BD. Endogenous lipid mediators in the resolution of airway inflammation. Eur Respir J 30: 980– 992, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hisatsune A, Hyun SW, Lee IJ, Georas S, Kim KC. YY1 transcription factor is not responsible for the negative regulation of hamster Muc1 transcription. Anticancer Res 24: 235– 240, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holden NS, Tacon CE. Principles and problems of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 63: 7– 14, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holden NS, Squires PE, Kaur M, Bland R, Jones CE, Newton R. Phorbol ester-stimulated NF-κB-dependent transcription: roles for isoforms of novel protein kinase C. Cell Signal 20: 1338– 1348, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jany B, Betz R, Schreck R. Activation of the transcription factor NF-κB in human tracheobronchial epithelial cells by inflammatory stimuli. Eur Respir J 8: 387– 391, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-γ agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature 391: 82– 86, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jimenez-Lara AM, Clarke N, Altucci L, Gronemeyer H. Retinoic-acid-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Trends Mol Med 10: 508– 515, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim KC, Lillehoj EP. MUC1 mucin: a peacemaker in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 39: 644– 647, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim SR, Lee KS, Park HS, Park SJ, Min KH, Jin SM, Lee YC. Involvement of IL-10 in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-mediated anti-inflammatory response in asthma. Mol Pharmacol 68: 1568– 1575, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kodera Y, Takeyama K, Murayama A, Suzawa M, Masuhiro Y, Kato S. Ligand type-specific interactions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ with transcriptional coactivators. J Biol Chem 275: 33201– 33204, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koga T, Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Lu W, Miyata T, Isohama Y, Kim KC. TNF-α induces MUC1 gene transcription in lung epithelial cells: its signaling pathway and biological implication. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L693– L701, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kovarik A, Peat N, Wilson D, Gendler SJ, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Analysis of the tissue-specific promoter of the MUC1 gene. J Biol Chem 268: 9917– 9926, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Hisatsune A, Lu W, Isohama Y, Miyata T, Kim KC. Neutrophil elastase stimulates MUC1 gene expression through increased Sp1 binding to the MUC1 promoter. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L355– L362, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Koga T, Isohama Y, Miyata T, Kim KC. The signaling pathway involved in neutrophil elastase stimulated MUC1 transcription. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37: 691– 698, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kyo Y, Kato K, Park YS, Gajhate S, Umehara T, Lillehoj EP, Suzaki H, Kim KC. Anti-inflammatory role of MUC1 mucin during nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 46: 149– 156, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lagow EL, Carson DD. Synergistic stimulation of MUC1 expression in normal breast epithelia and breast cancer cells by interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α. J Cell Biochem 86: 759– 772, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee IJ, Hyun SW, Nandi A, Kim KC. Transcriptional regulation of the hamster Muc1 gene: identification of a putative negative regulatory element. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L160– L168, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee KS, Park SJ, Hwang PH, Yi HK, Song CH, Chai OH, Kim JS, Lee M, Lee YC. PPAR-γ modulates allergic inflammation through upregulation of PTEN. FASEB J 19: 1033– 1035, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li Y, Dinwiddie DL, Harrod KS, Jiang Y, Kim KC. Anti-inflammatory effect of MUC1 during respiratory syncytial virus infection of lung epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L558– L563, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liang J, Jiang D, Griffith J, Yu S, Fan J, Zhao X, Bucala R, Noble PW. CD44 is a negative regulator of acute pulmonary inflammation and lipopolysaccharide-TLR signaling in mouse macrophages. J Immunol 2007; 178: 2469– 2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lillehoj EP, Han F, Kim KC. Mutagenesis of a Gly-Ser cleavage site in MUC1 inhibits ectodomain shedding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 307: 743– 749, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu WS, Heckman CA. The sevenfold way of PKC regulation. Cell Signal 10: 529– 542, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu W, Hisatsune A, Koga T, Kato K, Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Chen W, Cross AS, Gendler SJ, Gewirtz AT, Kim KC. Cutting edge: enhanced pulmonary clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Muc1 knockout mice. J Immunol 176: 3890– 3894, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu W, Lillehoj EP, Kim KC. Effects of dexamethasone on Muc5ac mucin production by primary airway goblet cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L52– L60, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mu YM, Yanase T, Nishi Y, Takayanagi R, Goto K, Nawata H. Combined treatment with specific ligands for PPARγ:RXR nuclear receptor system markedly inhibits the expression of cytochrome P450arom in human granulosa cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 181: 239– 248, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ogawa Y, Duru EA, Ameredes BT. Role of IL-10 in the resolution of airway inflammation. Curr Mol Med 8: 437– 445, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Okada M, Yan SF, Pinsky DJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) activation suppresses ischemic induction of Egr-1 and its inflammatory gene targets. FASEB J 16: 1861– 1868, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pemberton LF, Rughetti A, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Gendler SJ. The epithelial mucin MUC1 contains at least two discrete signals specifying membrane localization in cells. J Biol Chem 271: 2332– 2340, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Perez A, van Heeckeren AM, Nichols D, Gupta S, Eastman JF, Davis PB. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in cystic fibrosis lung epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L303– L313, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ren J, Agata N, Chen D, Li Y, Yu WH, Huang L, Raina D, Chen W, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Human MUC1 carcinoma-associated protein confers resistance to genotoxic anticancer agents. Cancer Cell 5: 163– 175, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roth M, Black JL. Transcription factors in asthma: Are transcription factors a new target for asthma therapy? Curr Drug Targets 7: 589– 595, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Royce SG, Tang ML. The effects of current therapies on airway remodeling in asthma and new possibilities for treatment and prevention. Curr Mol Pharmacol 2: 169– 181, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Samuelsson B. Arachidonic acid metabolism: role in inflammation. Z Rheumatol 50: 3– 6, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Serhan CN, Devchand PR. Novel anti-inflammatory targets for asthma. A role for PPARγ? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 24: 658– 661, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shalom-Barak T, Nicholas JM, Wang Y, Zhang X, Ong ES, Young TH, Gendler SJ, Evans RM, Barak Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ controls MUC1 transcription in trophoblasts. Mol Cell Biol 24: 10661– 10669, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shanks KK, Guang W, Kim KC, Lillehoj EP. Interleukin-8 production by human airway epithelial cells in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates expressing type a or type b flagellins. Clin Vaccine Immunol 17: 1196– 1202, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Thatcher TH, Maggirwar SB, Baglole CJ, Lakatos HF, Gasiewicz TA, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice develop heightened inflammatory responses to cigarette smoke and endotoxin associated with rapid loss of the NF-κB component RelB. Am J Pathol 170: 855– 864, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ueno K, Koga T, Kato K, Golenbock DT, Gendler SJ, Kai H, Kim KC. MUC1 mucin is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38: 263– 268, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vidal-Puig A, Jimenez-Linan M, Lowell BB, Hamann A, Hu E, Spiegelman B, Flier JS, Moller DE. Regulation of PPARγ gene expression by nutrition and obesity in rodents. J Clin Invest 97: 2553– 2561, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ward JE, Tan X. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ligands as regulators of airway inflammation and remodelling in chronic lung disease. PPAR Res 2007: 14983, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Woerly G, Honda K, Loyens M, Papin JP, Auwerx J, Staels B, Capron M, Dombrowicz D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ downregulate allergic inflammation and eosinophil activation. J Exp Med 198: 411– 421, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wu W, Booth JL, Coggeshall KM, Metcalf JP. Calcium-dependent viral internalization is required for adenovirus type 7 induction of IL-8 protein. Virology 355: 18– 29, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yamada M, Horiguchi K, Umezawa R, Hashimoto K, Satoh T, Ozawa A, Shibusawa N, Monden T, Okada S, Shimizu H, Mori M. Troglitazone, a ligand of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, stabilizes NUCB2 (Nesfatin) mRNA by activating the ERK1/2 pathway: Isolation and characterization of the human NUCB2 gene. Endocrinology 151: 2494– 2503, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yanase T, Mu YM, Nishi Y, Goto K, Nomura M, Okabe T, Takayanagi R, Nawata H. Regulation of aromatase by nuclear receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 79: 187– 192, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhou W, Hashimoto K, Goleniewska K, O'Neal JF, Ji S, Blackwell TS, Fitzgerald GA, Egan KM, Geraci MW, Peebles RS., Jr Prostaglandin I2 analogs inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production and T cell stimulatory function of dendritic cells. J Immunol 178: 702– 710, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]