Abstract

Among the various cardiac contractility parameters, left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) and maximum dP/dt (dP/dtmax) are the simplest and most used. However, these parameters are often reported together, and it is not clear if they are complementary or redundant. We sought to compare the discriminative value of EF and dP/dtmax in assessing systolic dysfunction after myocardial infarction (MI) in swine. A total of 220 measurements were obtained. All measurements included LV volumes and EF analysis by left ventriculography, invasive ventricular pressure tracings, and echocardiography. Baseline measurements were performed in 132 pigs, and 88 measurements were obtained at different time points after MI creation. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves to distinguish the presence or absence of an MI revealed a good predictive value for EF [area under the curve (AUC): 0.998] but not by dP/dtmax (AUC: 0.69, P < 0.001 vs. EF). Dividing dP/dtmax by LV end-diastolic pressure and heart rate (HR) significantly increased the AUC to 0.87 (P < 0.001 vs. dP/dtmax and P < 0.001 vs. EF). In naïve pigs, the coefficient of variation of dP/dtmax was twice than that of EF (22.5% vs. 9.5%, respectively). Furthermore, in n = 19 pigs, dP/dtmax increased after MI. However, echocardiographic strain analysis of 23 pigs with EF ranging only from 36% to 40% after MI revealed significant correlations between dP/dtmax and strain parameters in the noninfarcted area (circumferential strain: r = 0.42, P = 0.05; radial strain: r = 0.71, P < 0.001). In conclusion, EF is a more accurate measure of systolic dysfunction than dP/dtmax in a swine model of MI. Despite the variability of dP/dtmax both in naïve pigs and after MI, it may sensitively reflect the small changes of myocardial contractility.

Keywords: contractility, cardiac function, pig, strain imaging, receiver operater characteristic curves, peak rate of the left ventricular pressure systolic increase over time

with the worldwide increase in heart disease, partly due to the aging population, many therapeutic approaches are being developed and evaluated on a daily basis. In this context, reliable tools to measure cardiac dysfunction and evaluate therapeutic efficacy are essential. Many invasive and noninvasive cardiac function and contractility parameters are available to that end (36). Among these, the left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) is the simplest and most used parameter and the best available prognostic predictor in patients with systolic heart failure (5, 10, 19, 25, 36). However, EF is afterload dependent; it decreases to zero regardless of contractile state when afterload is infinite (14). After extensive investigations focused on pressure-volume loops (29, 34), load-independent indicators obtained from pressure-volume loops have become the gold standards of measuring cardiac contractility and thus are the current benchmarks for comparison with other contractility indexes. However, the application of these indexes to in vivo studies remains challenging (1, 17, 24), and some of these indicators are contingent on changes in ventricular compliance (4). Furthermore, precise measurements of LV volumes for pressure-volume analysis often requires the delicate placement of a conductance catheter in the ventricular cavity, which can be especially challenging when the peripheral arterial approach is indicated. Another invasive indicator, the peak rate of the LV pressure systolic increase over time, calculated as maximum dP/dt (dP/dtmax), is a simple indicator of cardiac contractility (14, 21, 28). Numerous studies have used dP/dtmax with convincing results (9, 20, 22, 32, 35); however, this index is known to be preload dependent (23, 31), and it is also affected by the heart rate (HR) (8, 37). Both EF and dP/dtmax thus have advantages and limitations, and they are often reported simultaneously in studies while it is not clear if they are complementary or redundant. We sought to compare the discriminative value of EF and dP/dtmax in assessing systolic dysfunction after myocardial infarction (MI) in swine.

METHODS

Animal model.

The experimental protocols complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and standards of United States regulatory agencies. They were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. All animals underwent hemodynamic and volume measurements before any interventions that may affect these parameters. All animals that received treatments to specifically influence cardiac function before the measurements were excluded from the study. Yorkshire pigs were premedicated using intramuscular Telazol (8.0 mg/kg, Fort Dodge, IA). After the placement of an intravenous injection line, animals were intubated and ventilated with 100% O2. Pigs were positioned in dorsal recumbency, and general anesthesia was maintained with intravenous Propofol (6–8 mg·kg−1·h−1) throughout the procedure. Electrocardiograms and pulse oximeter measurements were recorded at 5-min intervals. Continuous monitoring with an intravenous saline infusion was maintained for a period of 30 min to stabilize the hemodynamic status. A transthoracic echocardiographic examination was performed to exclude major structural heart diseases.

Pressure measurements.

Under sterile conditions, a percutaneous puncture provided arterial access and allowed sheath placement. After sheath insertion, heparin (100 IU/kg iv) was administered to maintain an activated coagulation time of 250–300 s. Through the femoral arterial sheath, a Millar catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was advanced to the LV to measure the following hemodynamic parameters: LV maximum pressure, LV end-diastolic pressure (EDP), dP/dtmax, and HR. MPVS Ultra (Millar Instruments) was used to acquire analog data and convert it to digital data. Data analysis was performed using iox2 (Emka Technologies, Falls Church, VA). All measurements were performed after the confirmation of hemodynamic stability for 3 min. An average of two respiratory cycles was used for the analysis of each parameter.

Volume measurements.

Immediately after the pressure measurements, left ventriculography was performed using a contrast agent injected at a high rate. Clear delineation of the ventricular border enabled an automatic trace of the ventricular cavity. Electrodes of the Millar catheter placed 7 mm apart were used for the calibration of the length of the LV measured on the ventriculographic image. End-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV) were calculated from left ventriculography by the area-length method (30). Stroke volume (SV) was calculated EDV − ESV, and EF was calculated as SV/EDV. Body surface area (in m2) was calculated (16) as 734 × body weight0.656, and volume parameters were divided by the body surface area to calculate volume indexes.

MI creation.

The creation of the MI has been described in detail elsewhere (12). Briefly, after cardiac performance was evaluated in naïve pigs, a bolus of Amiodarone (1 mg/kg) was given intravenously over 10 min, followed by a continuous infusion at the rate of 1 mg/min for the duration of the procedure. A 7-Fr hockey-stick catheter (Cordis, Miami, FL) was advanced to the left coronary artery, and a 0.014-in. guide wire (Abbott, Park, IL) was advanced into the left anterior descending artery. An 8-mm-long, 4.0-mm VOYAGER over-the-wire balloon (Abbott) was advanced beyond the first branch. The balloon was then inflated to 3 atm for 90–120 min, followed by an embolic coil implantation in some of the animals (n = 19). The remaining animals were reperfused without a coil. After the confirmation of hemodynamic stability, animals were allowed to recover, housed in their cages, and examined daily for any signs of pain or distress.

Echocardiographic strain measurements.

A Philips iE-33 ultrasound system (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) was used to acquire echocardiographic data with a multifrequency imaging transducer. Two-dimensional (2-D) cross-sectional images of the parasternal short axis of the LV were obtained at the level of the papillary muscle, with a high frame rate. Data spanning at least three consecutive heartbeats were acquired and stored as digital images. The 2-D images were loaded into the Q-lab application (Philips Medical Systems) for strain analysis using a speckle-tracking algorithm. The LV was divided into six segments and categorized into three zones: infarct, border, and remote areas. Circumferential and radial strains were analyzed for each area.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE except in Fig. 4, where means ± SD are shown. The coefficient of variation was calculated by dividing the SD by the mean. Pearson's correlation and linear regression were used to examine the direction and strength of the relationships between the study variables, and corresponding scatterplots were generated. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to assess the ability of various parameters to determine the presence of MI, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated. Comparisons of AUCs were performed using the nonparametric approach. A paired t-test was used to compare preinfarct (naïve) and post-MI measurements taken serially on animals at each time point. Relative changes of EF and dP/dtmax before and after MI were obtained in animals with MI. A Bland-Altman plot of the difference between relative post-MI EF change and relative post-MI dP/dtmax change (y-axis) against their average (x-axis) was used to measure agreement between the two parameters in detecting post-MI change. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Fig. 4.

Comparative variability of EF and dP/dtmax in naïve pigs (n = 132). Values are means ± SD. The coefficient of variation of EF was 9.4%, and that of dP/dtmax was 22.5%.

RESULTS

A total of 220 measurements were obtained. Baseline measurements (naïve animals) before any intervention were performed in 132 pigs, and all the pigs underwent MI creation subsequently. Eighty-eight measurements from pigs that survived after MI creation and did not receive any treatment to specifically influence cardiac function were assigned to post-MI measurements. Multiple post-MI measurements were performed in nine pigs at different time points. LV pressure and volume data at each time points are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

LV size and function before and after myocardial infarction

| Myocardial Infarction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | 2 days | 7 days | 1 mo | 3 mo | |

| Number of measurements | 132 | 8 | 23 | 48 | 9 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 70.5 ± 0.6 | 38.4 ± 2.1* | 40.1 ± 1.3* | 37.0 ± 1.2* | 36.3 ± 3.1* |

| Maximum dP/dt, mmHg/s | 2020 ± 39 | 1817 ± 113* | 2006 ± 109 | 1567 ± 49* | 1605 ± 65* |

| Maximum LV pressure, mmHg | 106 ± 1.4 | 96 ± 2.7 | 106 ± 3* | 114 ± 2* | 124 ± 3.7 |

| End-diastolic pressure, mmHg | 14.1 ± 0.4 | 20.2 ± 2.3* | 22.0 ± 1.8* | 25.8 ± 1.2* | 19.2 ± 2.3 |

| Body weight, kg | 19.2 ± 0.1 | 20.3 ± 0.4 | 20.5 ± 0.2* | 24.8 ± 0.2* | 38.2 ± 1.3* |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 75 ± 2 | 111 ± 10* | 98 ± 4* | 70 ± 3 | 74 ± 4 |

| EDV, ml | 38.1 ± 0.5 | 49.5 ± 1.9 | 59.2 ± 2.0* | 81.8 ± 2.5* | 109.9 ± 7.3* |

| EDV index, ml/m2 | 74.9 ± 1.0 | 93.6 ± 3.3 | 111.4 ± 3.7* | 135.5 ± 4.1* | 138.0 ± 9.7* |

| ESV, ml | 11.2 ± 0.3 | 30.4 ± 1.4* | 35.8 ± 1.6* | 52.5 ± 2.5* | 70.9 ± 6.8* |

| ESV index, ml/m2 | 22.1 ± 0.6 | 57.4 ± 2.4* | 67.4 ± 3.1* | 87.1 ± 4.1* | 89.5 ± 9.2* |

| SV, ml | 26.8 ± 0.4 | 19.1 ± 1.4* | 23.4 ± 0.9 | 29.2 ± 0.7 | 38.8 ± 3.0* |

| SV index, ml/m2 | 52.5 ± 0.8 | 36.1 ± 2.6* | 43.9 ± 1.7* | 48.4 ± 1.1* | 48.3 ± 3.1 |

Values are means ± SE. LV, left ventricular; EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; SV, stroke volume.

P < 0.05 vs. baseline naïve measurements (by paired t-test).

Detection of MI.

ROC curves for various parameters were generated to compare their ability to detect MI. AUCs for EF and dP/dtmax to identify pigs with MI were 0.998 and 0.69 (P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 1A). The ROC curves for volume parameters are shown in Fig. 1B. Both the ESV index and EDV index appeared to be excellent predicting factors for detecting MI, and AUCs were 0.998 and 0.98, respectively. However, the AUC of the SV index remained small (0.70) compared with that of the ESV index (P < 0.001) and EDV index (P < 0.001). The ratio of dP/dtmax over EDP significantly increased the AUC compared with that of dP/dtmax alone (P < 0.001). Further adjustment through division by HR was also associated with an increased AUC without outperforming the adjustment on EDP (P < 0.001 vs. dP/dtmax alone and P = 0.13 vs. dP/dtmax/EDP; Fig. 2). The AUC for dP/dtmax adjusted on EDP or adjusted on EDP and HR remained significantly lower than the AUC for EF (P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Receover operator characteristic (ROC) curves of various parameters to predict myocardial infarction (MI), with areas under the curves (AUCs). A: ejection fraction (EF) and maximum dP/dt (dP/dtmax). B: left ventricular (LV) volumes adjusted with body surface area. While EF, the end-systolic volume index (ESVI), and the end-diastolic volume index (EDVI) were excellent predictors, dP/dtmax and the stroke volume index (SVI) were less useful to predict MI.

Fig. 2.

ROC curves, including AUCs, for dP/dtmax and its adjusted values to predict MI. Adjustment of dP/dtmax with end-diastolic pressure (EDP) significantly improved the predictive accuracy. Further adjustment with heart rate (HR) showed an additional increase in AUC.

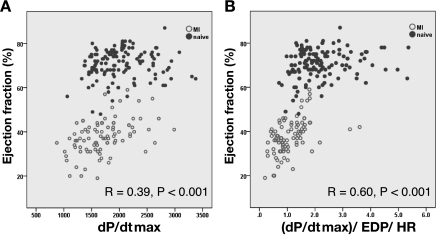

Correlation of EF and dP/dtmax and their distribution.

A scatterplot of EF versus dP/dtmax is shown in Fig. 3A. Only a weak correlation was found between EF and dP/dtmax. Adjustment of dP/dtmax with EDP and HR strengthened the correlation (Fig. 3B). Figure 4 shows the means and SDs of the values of EF and dP/dtmax in naïve pigs, where we assume little variability in cardiac function. However, the coefficient of variation was twice higher for dP/dtmax than for EF, accounting for a >20% variability range for dP/dtmax (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

A: correlation between EF and dP/dtmax. B: correlation between EF and (dP/dtmax)/EDP/HR. Division of dP/dtmax by EDP and HR improved the correlation to EF.

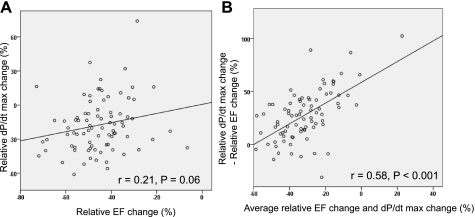

Relative change before and after MI.

There was no statistically significant correlation between the deterioration of EF and the deterioration of dP/dtmax caused by MI, measured as relative changes of EF and dP/dtmax associated with MI (r = 0.21, P = 0.06; Fig. 5A). A Bland-Altman plot was used to assess the agreement of EF and dP/dtmax in measuring the deterioration of LV function after MI (Fig. 5B). It revealed better agreement when the relative deterioration (measured as the average of relative deterioration of both parameters) was large; however, EF showed higher sensitivity to MI (higher EF relative deterioration) when the average relative deterioration was small.

Fig. 5.

A: scatterplot of relative changes of EF and dP/dtmax before and after MI. No significant correlation was found between the relative changes of EF and dP/dtmax. Note that while EF decreased after MI in all animals, the relative change of dP/dtmax was not always negative. B: Bland-Altman analysis comparing relative EF change and relative dP/dtmax change after MI. A modest linear correlation was found among the plots, indicating more correlation between EF and dP/dtmax when the relative decrease was large.

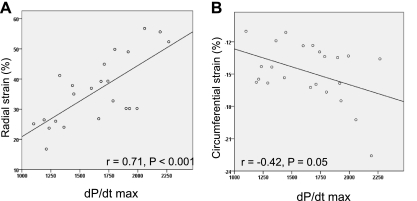

dP/dtmax and regional LV function.

To investigate whether the wide distribution of dP/dtmax change was partly due to increased contractility in the remote myocardium, echocardiographic strain analysis was performed in 23 pigs with MI. Pigs with an EF of 36–40% (means ± 2SE of the entire MI pig group) were chosen so that the relation could be assessed in pigs with comparable EF. While no correlation was found between the strain values in the infarct area and dP/dtmax, moderate correlation was found between both radial and circumferential strain of the remote area and dP/dtmax (r = 0.71, P < 0.001, and r = −0.42, P < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Scatterplot of dP/dtmax and echocardiographic strain parameters in 23 pigs with similar EFs after MI. Whereas circumferential strain showed weak correlation with dP/dtmax, radial strain showed a moderate correlation with dP/dtmax.

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to compare and contrast the accuracy of EF and dP/dtmax in the assessment of LV systolic dysfunction after MI and to further delineate the distinct value of measuring EF and dP/dtmax in that assessment. We found that 1) systolic dysfunction after MI was better detected by EF compared with dP/dtmax; 2) the ESV index as well as the EDV index were also good predictors of systolic dysfunction after MI; 3) adjustment of dP/dtmax to EDP and to HR increased its accuracy in detecting MI (however, EF remained a far better predictor of MI); and 4) in the animals with comparable EF after MI, dP/dtmax showed a significant correlation to the regional function of the noninfarcted remote area.

The assessment of LV systolic function remains the target of extensive efforts, and many parameters are used. Currently, EF and dP/dtmax are both widely used and accepted parameters to assess cardiac contractility with established advantages and limitations. However, they are often reported together, and it is not clear whether they are redundant or complementary, and whether one is more accurate than the other in the assessment of systolic dysfunction. In fact, limited information is available on the direct comparison of these parameters. To our knowledge, this is the first study that compared these widely used fundamental parameters in large numbers of animals with a clinically relevant ischemic heart failure model. Our results show EF to be more reliable than dP/dtmax in detecting systolic dysfunction after MI. We thought that this superiority of EF over dP/dtmax was due to the well-known preload dependence of dP/dtmax (14, 26), and we compared EF to dP/dtmax adjusted on EDP for that matter, showing improved accuracy of the adjusted parameter that, nonetheless, did not reach the accuracy of EF. In addition, the measurement of post-MI LV remodeling by the ESV index and EDV index appeared to have an excellent predictive value as well. In our study, we insisted on comparing and correlating non-overlapping parameters. Therefore, in contrast to EF and LV volume indexes, dP/dtmax is derived from the LV pressure-time curve, and the preload adjustment of dP/dtmax was done by dividing dP/dtmax by EDP, independently of volume measurements.

The EF-dP/dtmax Bland-Altman plot indicates that with more severe depression of cardiac function after MI, both EF and dP/dtmax show a comparable relative decrease. However, when the cardiac function is less impaired, the relative decrease of dP/dtmax is smaller compared with that of EF. One explanation is that dP/dtmax decreases when there is a global ventricular systolic dysfunction (more likely in MI with very low EF) but can be compensated by the noninfarcted area when the functional impairment is limited. Significant correlation between dP/dtmax and remote area regional function in pigs with nearly equal and reduced EF supports the latter hypothesis. Therefore, dP/dtmax can be modulated bidirectionally, in a more sensitive way than measures of global functional impairment, such as EF. Together with the lack of connection with LV volume remodeling, this explains the low predictive value of dP/dtmax for detecting MI.

Most studies that have used dP/dtmax-related parameters had similar HRs between the animals (3, 15, 18), which makes the Treppe effect less likely to play a role (37). However, not all animals have equivalent HRs, which can also fluctuate with some of the treatment regimens. Furthermore, while dP/dtmax is usually independent of afterload since it derives from the pressure change before the aortic valve opening, it is preload dependent (14, 26). The superiority of EF to dP/dtmax is partly due to the fact that EF = SV/EDV and thus EF accounts for the preload, in contrast with the preload dependence of dP/dtmax. This is supported by our results showing an improved accuracy of (dP/dtmax)/EDP compared with dP/dtmax alone in detecting MI and by the literature, where the slope of dP/dtmax versus EDP is an accepted load-independent parameter of LV systolic function (8, 31, 37). Thus, the adjustment of dP/dtmax, mostly with EDP, increased its predictive value for MI detection. Several other factors, such as longitudinal contraction (2), timing of aortic valve opening (39), and size of the LV (27), have a certain degree of influence on dP/dtmax. In fact, in the present study, for naïve animals with assumed normal and similar cardiac function, the coefficient of variation in dP/dtmax was 22.5%, whereas that of EF was only 9.4%. Although we included only nondiseased animals of similar sizes (19 ± 2 kg) that were studied under identical anesthesia conditions, the twice higher variability of dP/dtmax compared with EF is an additional drawback of this parameter, more sensitive to measured or unmeasured individual interanimal variation in experimental conditions, such as response to anesthetic drugs. In addition, as shown in Fig. 5A, some of the animals even showed increased dP/dtmax after MI. Thus, this value may not be suitable for interanimal comparison or for the comparison of different time points in the identical animal. Instead, the sensitive response to various factors is an advantage for the assessment of small changes in contractility during continuous or consecutive measurements, where many of the factors remain consistent.

Our results demonstrated a moderate correlation between EF and (dP/dtmax)/EDP/HR. This implies that EF is a parameter that integrates contractility, measured by pressure rise, and HR. Furthermore, as mentioned above, EF also reflects LV remodeling. Higher HR (6–7, 13) and larger size of the heart (11, 33, 38) are established predictors of poor outcomes in patients with systolic heart failure. As such, EF is a comprehensive parameter of various important factors closely related to the patients' prognosis. This may explain why EF is a powerful predictor of the prognosis of the patients with heart failure. Further studies are needed to verify that the superiority of EF over dP/dtmax in detecting myocardial infarction in our study translates in a superior clinical prognostic value for EF compared with dP/dtmax in patients with heart failure or after MI. In the spirit of our study, it may also be possible to establish a complementary prognostic value for dP/dtmax in situations where the predictive power of EF can be limited.

Limitations.

Because of the time separating post-MI measurements from naïve measurements, we cannot exclude the potential effect of animal growth. As the pigs grow, cardiac size increases and the ventricular volumes increase. This may be affecting the high predictive values obtained in volume parameters. To minimize the effect of growth, we used the volume indexes by dividing the volume with body surface area. In our experience, these indexes remain stable during the pigs' growth for the duration of our study period. The adjustment of dP/dtmax with HR and EDP by simply dividing this value may not be justified in some of the cases, since it does not always have linear relationships to HR and EDP. However, the higher correlation to EF and higher predictive value of MI after the division suggests that the influence of HR and EDP can be reduced by this adjustment.

Conclusions.

EF is more sensitive at detecting systolic dysfunction over dP/dtmax in a swine model of MI. Although adjustment with EDP and HR improved the predictive accuracy of dP/dtmax, it remained less powerful compared with EF. The results of the present study suggest that EF is a comprehensive parameter of contractility, HR, and LV remodeling. While dP/dtmax may be a useful tool to assess contractility within the same animal, EF is more suited for interanimal comparisons of systolic function after MI.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Leducq Foundation through the Caerus network (to R. J. Hajjar) and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-093183, HL-088434, HL-071763, HL-080498, HL-083156, and P20-HL-100396 (to R. J. Hajjar) and T32-HL-007824 (to E. R. Chemaly). D. Ladage was supported by the German Research Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.I., E.R.C., D.L., T.P.V., C.S.-G., Y.K., and R.J.H. conception and design of research; K.I., L.T., D.L., and J.A. performed experiments; K.I., E.R.C., L.T., and J.A. analyzed data; K.I., E.R.C., L.T., K.F., T.P.V., C.S.-G., Y.K., and R.J.H. interpreted results of experiments; K.I. and E.R.C. prepared figures; K.I., J.A., T.P.V., C.S.-G., and Y.K. drafted manuscript; K.I., E.R.C., L.T., K.F., D.L., T.P.V., C.S.-G., Y.K., and R.J.H. approved final version of manuscript; E.R.C., K.F., and R.J.H. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lauren Leonardson for providing excellent technical assistance and expertise.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aghajani E, Muller S, Kjorstad KE, Korvald C, Nordhaug D, Revhaugand A, Myrmel T. The pressure-volume loop revisited: Is the search for a cardiac contractility index a futile cycle? Shock 25: 370–376, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belghitia H, Brette S, Lafitte S, Reant P, Picard F, Serri K, Lafitte M, Courregelongue M, Dos Santos P, Douard H, Roudaut R, DeMaria A. Automated function imaging: a new operator-independent strain method for assessing left ventricular function. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 101: 163–169, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bolognesi R, Tsialtas D, Zeppellini R, Barilli AL, Cucchini F, Manca C. Early and subtle abnormalities of left ventricular function in clinically stable coronary artery disease patients with normal ejection fraction. J Card Fail 10: 304–309, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borlaug BA, Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Redfield MM. Contractility and ventricular systolic stiffening in hypertensive heart disease insights into the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 410–418, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohn JN, Johnson GR, Shabetai R, Loeb H, Tristani F, Rector T, Smith R, Fletcher R. Ejection fraction, peak exercise oxygen consumption, cardiothoracic ratio, ventricular arrhythmias, and plasma norepinephrine as determinants of prognosis in heart failure. The V-HeFT VA Cooperative Studies Group Circulation 87: VI5–V16, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diaz A, Bourassa MG, Guertin MC, Tardif JC. Long-term prognostic value of resting heart rate in patients with suspected or proven coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 26: 967–974, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, Danchin N, Ferrari R, Lopez Sendon JL, Steg PG, Tardif JC, Tavazzi L, Tendera M. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 823–830, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fried AG, Parker AB, Newton GE, Parker JD. Electrical and hemodynamic correlates of the maximal rate of pressure increase in the human left ventricle. J Card Fail 5: 8–16, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ginks MR, Sciaraffia E, Karlsson A, Gustafsson J, Hamid S, Bostock J, Simon M, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Rinaldi CA. Relationship between intracardiac impedance and left ventricular contractility in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace 13: 984–991, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gradman A, Deedwania P, Cody R, Massie B, Packer M, Pitt B, Goldstein S. Predictors of total mortality and sudden death in mild to moderate heart failure. Captopril-Digoxin Study Group J Am Coll Cardiol 14: 562–571, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grayburn PA, Appleton CP, DeMaria AN, Greenberg B, Lowes B, Oh J, Plehn JF, Rahko P, John Sutton M, Eichhorn EJ. Echocardiographic predictors of morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced heart failure: the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST). J Am Coll Cardiol 45: 1064–1071, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ishikawa K, Ladage D, Tilemann L, Fish K, Kawase Y, Hajjar RJ. Gene transfer for ischemic heart failure in a preclinical model. J Vis Exp; doi:10.3791/2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jouven X, Empana JP, Schwartz PJ, Desnos M, Courbon D, Ducimetiere P. Heart-rate profile during exercise as a predictor of sudden death. N Engl J Med 352: 1951–1958, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kass DA, Maughan WL, Guo ZM, Kono A, Sunagawa K, Sagawa K. Comparative influence of load versus inotropic states on indexes of ventricular contractility: experimental and theoretical analysis based on pressure-volume relationships. Circulation 76: 1422–1436, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kawase Y, Ly HQ, Prunier F, Lebeche D, Shi Y, Jin H, Hadri L, Yoneyama R, Hoshino K, Takewa Y, Sakata S, Peluso R, Zsebo K, Gwathmey JK, Tardif JC, Tanguay JF, Hajjar RJ. Reversal of cardiac dysfunction after long-term expression of SERCA2a by gene transfer in a pre-clinical model of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 1112–1119, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelley KW, Curtis SE, Marzan GT, Karara HM, Anderson CR. Body surface area of female swine. J Anim Sci 36: 927–930, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korvald C, Elvenes OP, Aghajani E, Myhre ES, Myrmel T. Postischemic mechanoenergetic inefficiency is related to contractile dysfunction and not altered metabolism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H2645–H2653, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liang CS, Frantz RP, Suematsu M, Sakamoto S, Sullebarger JT, Fan TM, Guthinger L. Chronic β-adrenoceptor blockade prevents the development of β-adrenergic subsensitivity in experimental right-sided congestive heart failure in dogs. Circulation 84: 254–266, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Likoff MJ, Chandler SL, Kay HR. Clinical determinants of mortality in chronic congestive heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated or to ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 59: 634–638, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin YD, Yeh ML, Yang YJ, Tsai DC, Chu TY, Shih YY, Chang MY, Liu YW, Tang AC, Chen TY, Luo CY, Chang KC, Chen JH, Wu HL, Hung TK, Hsieh PC. Intramyocardial peptide nanofiber injection improves postinfarction ventricular remodeling and efficacy of bone marrow cell therapy in pigs. Circulation 122: S132–141, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mason DT. Usefulness and limitations of the rate of rise of intraventricular pressure (dp-dt) in the evaluation of myocardial contractility in man. Am J Cardiol 23: 516–527, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Munch G, Rosport K, Bultmann A, Baumgartner C, Li Z, Laacke L, Ungerer M. Cardiac overexpression of the norepinephrine transporter uptake-1 results in marked improvement of heart failure. Circ Res 97: 928–936, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nejad NS, Klein MD, Mirsky I, Lown B. Assessment of myocardial contractility from ventricular pressure recordings. Cardiovasc Res 5: 15–23, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nordhaug D, Steensrud T, Korvald C, Aghajani E, Myrmel T. Preserved myocardial energetics in acute ischemic left ventricular failure–studies in an experimental pig model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 22: 135–142, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parameshwar J, Keegan J, Sparrow J, Sutton GC, Poole-Wilson PA. Predictors of prognosis in severe chronic heart failure. Am Heart J 123: 421–426, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perlini S, Meyer TE, Foex P. Effects of preload, afterload and inotropy on dynamics of ischemic segmental wall motion. J Am Coll Cardiol 29: 846–855, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pidgeon J, Miller GA, Noble MI, Papadoyannis D, Seed WA. The relationship between the strength of the human heart beat and the interval between beats. Circulation 65: 1404–1410, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Quinones MA, Gaasch WH, Alexander JK. Influence of acute changes in preload, afterload, contractile state and heart rate on ejection and isovolumic indices of myocardial contractility in man. Circulation 53: 293–302, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sagawa K, Suga H, Shoukas AA, Bakalar KM. End-systolic pressure/volume ratio: a new index of ventricular contractility. Am J Cardiol 40: 748–753, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sandler H, Dodge HT. The use of single plane angiocardiograms for the calculation of left ventricular volume in man. Am Heart J 75: 325–334, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schmidt HD, Hoppe H. Influence of the contractile state of the heart of the preload dependence of the maximal rate of intraventricular pressure rise dP/dt max. Cardiology 63: 112–125, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seo JS, Kim DH, Kim WJ, Song JM, Kang DH, Song JK. Peak systolic velocity of mitral annular longitudinal movement measured by pulsed tissue Doppler imaging as an index of global left ventricular contractility. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1608–H1615, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. John Sutton M, Pfeffer MA, Moye L, Plappert T, Rouleau JL, Lamas G, Rouleau J, Parker JO, Arnold MO, Sussex B, Braunwald E. Cardiovascular death and left ventricular remodeling two years after myocardial infarction: baseline predictors and impact of long-term use of captopril: information from the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) trial. Circulation 96: 3294–3299, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suga H, Sagawa K, Kostiuk DP. Controls of ventricular contractility assessed by pressure-volume ration, Emax. Cardiovasc Res 10: 582–592, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suzuki H, Shimano M, Yoshida Y, Inden Y, Muramatsu T, Tsuji Y, Tsuboi N, Hirayama H, Shibata R, Murohara T. Maximum derivative of left ventricular pressure predicts cardiac mortality after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Clin Cardiol 33: E18–E23, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. von Spiegel T, Wietasch G, Hoeft A. Basics of myocardial pump function. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2: 237–241, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wallace AG, Skinner NS, Jr, Mitchell JH. Hemodynamic determinants of the maximal rate of rise of left ventricular pressure. Am J Physiol 205: 30–36, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, Brandt PW, Whitlock RM, Wild CJ. Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation 76: 44–51, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wildenthal K, Mierzwiak DS, Mitchell JH. Effect of sudden changes in aortic pressure on left ventricular dp/dt. Am J Physiol 216: 185–190, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]