Abstract

This study examined the relations among alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide proneness in undergraduate college students (N = 996). As hypothesized, alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness were all significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness. The relation between experiencing alcohol-related problems and suicide proneness was, in part, accounted for by perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Additionally, the mediation via perceived burdensomeness was significantly stronger than the mediation via thwarted belongingness. Results suggest that it would be advisable for clinicians to be aware of students’ experiences with alcohol-related problems in conjunction with their levels of burdensomeness and belongingness when assessing for suicide risk

Keywords: Suicide proneness, alcohol-related problems, belongingness, burdensomeness

Suicidal behavior and alcohol use are major public health concerns in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2009). Suicide is the second leading cause of death among college students (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2010) accounting for approximately 1100 suicides each year (CDC, 2009). Moreover, approximately 18% of undergraduates report seriously considering a suicide attempt in their lifetime, while 47% of serious ideators endorse persistent ideation (Drum, Brownson, Denmark, & Smith, 2009). Given the clinical and public health significance of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among college students, there is considerable interest in identifying factors that increase the risk of suicidality in this population. Alcohol use and related problems have been found to be significant risk factors for suicide (Lamis, Malone, & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2010; Miller, Teti, Lawrence, & Weiss, 2010) and will be the focus of the current study.

Among alcohol using individuals, younger age, female gender, and White race have all been associated with suicidality (Garlow, 2002; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Friend, & Powell, 2009; Preuss et al., 2002). Moreover, alcohol use as a suicide risk factor has particular relevance to college students, a population which has high rates of past-year drinking (75.5%), heavy episodic drinking (18.7%) and alcohol use disorders (38.1%; Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004). Several studies indicate an association between alcohol use and suicidal behaviors in college students (e.g., Arria et al., 2009; Lamis, Ellis, Chumney, & Dula, 2009; Lamis, Malone, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Ellis, 2010). Specifically, alcohol use has been associated with increased rates of suicide ideation and attempts in cross-sectional studies (e.g., Gonzalez, Bradizza, & Collins, 2009; Schaffer, Jeglic, & Stanley, 2008; Stephenson, Pena-Shaff, & Quirk, 2006) and in prospective longitudinal research (Hills, Afifi, Cox, Bienvenu, & Sareen, 2009; Wines, Saitz, Horton, Lloyd-Travaglini, & Samet, 2004). Moreover, studies on university students have shown consumption of alcohol to be associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing alcohol-related problems (Carey & Correia, 1997; Cox, Hosier, Crossley, Kendall, & Roberts, 2006), which have been found to be related to suicidal behaviors (Kaslow et al., 2002; Sher, 2006; Windle & Windle, 2006). For example, Lamis, Malone, and Langhinrichsen-Rohling (2010) found that alcohol-related problems significantly predicted suicide risk in college women. Likewise, Pedersen (2008) concluded that alcohol-related problems significantly predicted suicidal ideation and attempts in a longitudinal sample of young adults. In the current study, alcohol-related problems are investigated as a potential risk factor for suicide in the context of Joiner’s (2005) interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide.

According to this theory, the most serious form of suicidal desire is caused by the simultaneous presence of two interpersonal constructs—thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Joiner, 2005). A thwarted sense of belonging results from an unmet need to belong to a valued relationship or group of people (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), while a sense of perceived burdensomeness results from the view that one’s existence burdens family, friends, and/or society (Joiner et al., 2002). Several studies have directly tested the role of these constructs in suicidality (see Van Orden et al., 2010 for a review). For instance, thwarted belongingness (Van Orden, Witte, James, et al., 2008) and perceived burdensomeness (Joiner et al., 2009) have been found to significantly predict suicidal ideation in samples of college students. Further, given that previous studies have demonstrated an association between drinking and interpersonal variables (e.g., Doumas, Blasey, & Mitchell, 2007), it would be expected that alcohol-related problems are related specifically to Joiner’s constructs.

Although a wealth of research has supported the association between the interpersonal constructs included in Joiner’s (2005) theory and suicidality, no studies to our knowledge have investigated perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness as potential mediators in the relation between alcohol-related problems and risk for suicide specifically in college students. However, two recent studies (Conner, Britton, Sworts, & Joiner, 2007; You, Van Orden, & Conner, 2011) were identified which examined the role of belonging in suicidal behaviors among individuals with substance use disorders. Conner and colleagues examined the association between thwarted belongingness and past suicide attempt among methadone maintenance patients at an urban university hospital. Results indicated that greater belongingness significantly decreased the odds of having a past suicide attempt. Similarly, You and associates investigated several indices of social connectedness including belongingness in participants recruited from four residential substance-use treatment programs. Results revealed that belongingness was a significant predictor of a history of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Although the above studies did not specifically assess alcohol-related problems, there is a high probability that individuals enrolled in treatment programs have experienced negative consequences related to their substance use (Donovan, Kivlahan, Doyle, Longabaug, & Greenfield, 2006). The current study aims to determine potential mediating roles that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may play in the alcohol-related problems-suicide risk link.

We will also expand on the available research by investigating suicide proneness, a construct related to suicide risk, as an outcome variable in all analyses. According to Lewinsohn and colleagues’ (Lewinsohn et al., 1995; Lewinsohn, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Rohde, & Langford, 2004) theory, suicide proneness consists of a single domain to which all varieties of potentially life-threatening and life-extending behaviors belong. Behaviors were broadly defined to include thoughts, feelings, and actions. Therefore, the suicide prone individual is one who is both engaging in life-threatening thoughts, feelings, and actions as well as failing to engage in various types of life-extending behaviors. Specifically, Lewinsohn et al. (1995) asserted that suicide proneness is comprised of four disparate suicide-related domains: death and suicide behaviors; illness and health behaviors; risk and injury behaviors; and self related behaviors. Recognizing these suicide-related domains was expected to facilitate the process of identifying individuals engaging in life-threatening behavior that may be less overtly suicidal and thus, missed by other assessment strategies. Lewinsohn and colleagues then constructed an instrument to measure the overall construct, the Life Attitudes Schedule-Short Form (LAS-SF), which has been successfully used to identify individuals who are at risk for having suicidal thoughts and engaging in suicidal and life-threatening behaviors (Rohde, Seeley, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Rohling, 2003). Use of this measure to assess suicide proneness and its associations with alcohol-related problems and the two interpersonal constructs of Joiner’s theory in college students will thus extend the existing literature on the suicidal behavior of young adults.

Consequently, the purpose of the current study is to examine these risk factors – alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness – all which have been hypothesized to be associated with suicidal proneness in college students. It is expected that a better understanding of the interplay among these variables will have implications for the improved identification and treatment of young adults at risk for suicide. Specifically, on the basis of existing literature and consistent with theory, we hypothesized that: (1) reports of experiencing alcohol-related problems would be positively correlated with suicide proneness; (2) perceived burdensomeness would be positively correlated with suicide proneness, (3) thwarted belongingness would be positively correlated with suicide proneness; 4) thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would both significantly mediate the relation between experiencing alcohol-related problems and suicidal proneness, and 5) the mediation via perceived burdensomeness would be significantly stronger than the mediation via thwarted belongingness. We anticipated perceived burdensomeness to be a stronger mediator than thwarted belongingness due to students often being dependent on their parents and having to answer to them when they encounter alcohol-related consequences. This may make them feel as if they are a burden on their families, in turn increasing their risk for suicide.

Method

Participants

Participants were 996 undergraduate students at a large Southeastern university who volunteered to participate in the study in return for extra credit. The sample was 70% female and 78% European American, which is comparable to gender and race distributions of undergraduate psychology majors at the institution where the present work was conducted. The average age was 19.2 years (SD = 1.3) and ages ranged from 18 to 24 years. The majority of the sample was in their freshman or sophomore year (76%) and 74% reported they were a member of a social fraternity or sorority. Fifty-eight percent of the participants reported they were single; whereas, 42% reported they were in a relationship. Sixty-four percent of the students reported living on campus with 36% living off campus.

Measures

All study participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire, the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI), the Interpersonal Needs Quesionnaire-12 (INQ-12), the Life Attitudes Schedule Short-Form (LAS-SF), and the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale-Form B (MCSD-B).

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI)

The RAPI (White & Labouvie, 1989) was used to assess alcohol-related problems common among college students (e.g., missing class, getting into fights or arguments, driving after drinking). The RAPI assesses the occurrence of 23 alcohol-related problems within the last year using a four-point scale (0 = never, 1 = 1–2 times, 2 = 3–5 times, 3 = 6–10 times, 4 = more than 10 times). Summed scores can range from 0 to 92. Some researchers (e.g., Thombs & Beck, 1994) have suggested a cutoff score of >15 to describe “high consequence drinkers.” In the current study, 34.3% of the sample scored above 15 on the RAPI. In order to maximize the information available for analysis, we used the total summed score as a continuous variable. Further, the total score on the RAPI was positively skewed (1.65) and leptokurtic (3.57), so we conducted a natural log transform of the score (plus one) to address normality issues with resulting skewness being acceptable (-.48) and slightly negative kurtosis (-.89). The RAPI has regularly demonstrated good internal consistency in college student samples (e.g., Cronbach’s α = 0.92, Carey & Correia, 1997). Similarly, in the present study, the internal consistency reliability estimate for the RAPI was .94.

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-12 (INQ-12)

The INQ-12 (Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, et al., 2008) is a measure of two main components of Joiner's (2005) interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide: 1) perceived burdensomeness and 2) thwarted belongingness. This measure contains seven items that assess perceived burdensomeness and five items that assess thwarted belongingness. An example of a burdensomeness item on the INQ-12 is, “These days, I think I have failed the people in my life” (Item 3). An example of a belongingness item is, “These days, other people care about me” (Item 8). All statements are rated on a seven-point scale from 1 (not at all true for me) to 7 (very true for me), with higher summed scores corresponding to higher levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, et al. (2008) reported good estimates of internal consistency for the thwarted belongingness (α = .85) and perceived burdensomeness (α = .89) items. In addition, they reported moderate correlations in the expected directions with measures of suicidality and depressive symptoms, in support of the items' construct validity. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha for thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness was .89 and .92, respectively. The perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness scales showed large floor effects, rendering normal-theory statistics inappropriate. For the purposes of this study, we treated both of these scales as left-censored normal, using a weighted least squares estimator.

The Life Attitudes Schedule-Short Form (LAS-SF)

The LAS-SF (Rohde, Lewinsohn, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Langford, 2004) is a 24-item self-report measure designed to assess current suicidal and health-related behaviors. Each item is scored as “true” or “false,” with the number of true responses being summed to obtain a total scale score. High scores are suggestive of greater suicide related and health risk concerns. Moreover, the total score on the LAS-SF has been found to correlate with both current suicide ideation and a history of past suicide attempts (Rohde et al., 2003). This scale has shown good reliability and validity estimates in clinical and non-clinical samples (Ellis & Rutherford, 2008; Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Lamis, 2008), and has been used successfully with college students in previous studies (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Arata, Bowers, O’Brien, & Morgan, 2004). In the current study, the coefficient alpha for the 24 LAS-SF items was .75.

The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale-Form B (MCSD-B)

The MCSD-B (Reynolds, 1982) is a measure designed to assess whether participants respond in a socially desirable manner and was included in the model as a possible covariate. The scale consists of 12 true-false items and was developed from the original Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960), which measures the response tendency to make socially desirable self-presentations, especially on self-report measures. Psychometric information regarding the MCSD-B indicates that it has an adequate internal consistency estimate of .76, and, in similar research using college students, the alpha was .88 (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004). The internal consistency estimate in the current sample was 0.90.

In addition to gender and ethnicity, participants self-reported on social club membership (i.e., fraternity/sorority affiliation), relationship status, and residency status (e.g., Greek housing, off-campus apartment), all of which may provide social support and a sense of belonging to an individual experiencing distress during college life. These support networks may serve as protective factors against one’s propensity to engage in suicidal behaviors (Joiner, 2005) and were included in the mediation model as possible covariates. Although the majority of participants were either freshmen or sophomores, researchers (e.g., Mallett et al., 2011; Pryor et al., 2010) have documented that incoming freshmen are more likely to engage in high risk behaviors and report lower levels of emotional health than older students. We included age as a covariate for these reasons. Additionally, given that researchers (e.g., Miotto & Pretti, 2008) have found that those who scored higher on measures of social desirability reported fewer thoughts about suicide, social desirability was also included as a covariate.

Procedure

Data collection was conducted through an online survey over the course of two semesters, with approximately equal numbers of participants completing the study during the fall and spring. Participants voluntarily chose to complete the survey outside of class time in return for extra credit in their psychology course. Students were told of the study in regularly scheduled classes and through a posting on the online participant pool site. Participants completed a demographic survey and the study measures, which were presented in a randomized order for each participant. Prior to data collection, electronic informed consent was obtained from participants. They were advised that some items in the survey were personal in nature and that the participants remained anonymous. Participants were advised that they were free to leave any items blank. No negative reactions were reported by participants. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study in advance of data collection, and ethical procedures were followed throughout the study.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the four primary study variables – (log−) alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide proneness, are presented above the diagonal in Table 1. Partial correlations of the four variables, covarying age, gender, ethnicity, social desirability, social club membership, relationship status, and residency status appear below the diagonal. All correlations are positive and significant, p’s < .001, regardless of the inclusion of covariates. These results are consistent with Hypothesis One (reports of experiencing alcohol-related problems would be significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness), Hypothesis Two (perceived burdensomeness would be significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness), and Hypothesis Three (thwarted belongingness would be significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness).

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix, Means, and Standard Deviations of Study Measures

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol Related Problems (log-transformed) | -- | .22 | .14 | .41 |

| 2. Perceived Burdensomeness | .25 | -- | .59 | .51 |

| 3. Thwarted Belongingness | .15 | .60 | -- | .39 |

| 4. Suicidal Proneness | .44 | .52 | .40 | -- |

|

| ||||

| Mean | 13.65a | 5.80b | 6.91b | 5.24 |

| SD | 14.37a | 10.00b | 8.27b | 3.19 |

Note. N = 996. Tabled values are zero-order correlations (above diagonal) and partial correlations (below diagonal) after covarying out age, gender, ethnicity, social desirability, social club membership, relationship status and residency status. All values are significant, p’s < .001.

Nontransformed.

Adjusted for censoring

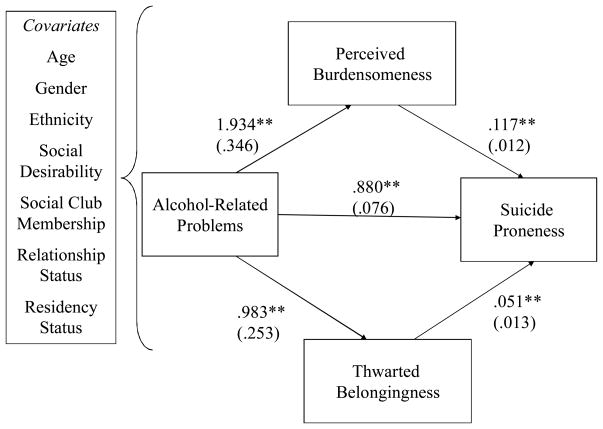

The primary hypotheses regarded the mediation of the link from alcohol problems to suicide proneness by perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. We tested these mediated paths via a path model estimated in Mplus v.6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). The model is diagrammed in Figure 1, with key estimated path coefficients shown. Due to the inclusion of censored variables (belongingness and burdensomeness), we used mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimation. The models were saturated.

Figure 1.

Mediation model with unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors

Note. ** p < .001.

Mediated paths and total effects were tested as the product of coefficients, using the percentile bootstrap for confidence intervals as recommended by MacKinnon (2008). The total effect of alcohol problems on suicide proneness was positive and significant, with a point estimate of 1.16, 95% CI 0.99 – 1.34, standardized estimate of 0.42. This effect was significantly mediated by both perceived burdensomeness, ab = 0.23, 95% CI 0.14 – 0.32, and thwarted belongingness, ab = 0.05, 95% CI 0.02 – 0.09. The standardized indirect effects for perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were .08 and .01, respectively. Thus, a 1 standard deviation difference in alcohol-related problems predicts a .42 difference in suicide proneness, and .08 of the difference is via perceived burdensomeness, and .01 is via thwarted belongingness. We constructed an estimate of the difference between the two mediated effects, which was significant in the direction of greater mediation via perceived burdensomeness than via thwarted belongingness, estimate of 0.18, 95% CI 0.09 – 0.28.

Discussion

The present study explored the associations among alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide proneness in undergraduate college students. Previous research (e.g., Lamis, Malone, & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2010; Lamis, Malone, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Ellis, 2010) has implicated alcohol use and related problems as significant risk factors for suicide proneness in college students. However, no studies, to our knowledge, have investigated the relationship between alcohol-related problems and the two interpersonal constructs included in Joiner’s (2005) theory – perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Moreover, there is limited research on these variables and their association with suicidal behaviors in college student samples. Consequently, the current study addresses an important gap in the literature by examining these relations and also testing Joiner’s interpersonal constructs as potential mediators in the alcohol-related problems-suicide proneness link.

The results indicated that assessing individuals for alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness is likely to aid in the prediction of suicide risk in college students. The levels of alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide proneness reported by participants in the current study are similar to those reported in previous research on college students (see Freedenthal, Lamis, Osman, Kahlo, & Gutierrez, 2011; Lamis, Malone, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2010). As hypothesized, alcohol-related problems were significantly positively correlated with suicide proneness. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that individuals who experience negative consequences related to alcohol use may be at an increased risk of being suicidal (Lamis, Malone, Langinrichsen-Rohling, 2010; Windle & Windle, 2006). College students in particular may consume higher levels of alcohol to deal with life stressors (Park & Levenson, 2002), which place them at an increased risk for experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences. As a result, students who do encounter problematic drinking-related outcomes may not be able to effectively cope and in turn begin to entertain the idea of suicide.

Consistent with the second hypothesis and Joiner’s (2005) theory, perceived burdensomeness was found to be significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness. This result corroborates past research in undergraduate college students and young adults (Davidson, Wingate, Rasmussen, & Slish, 2009; Joiner et al., 2009). This finding suggests that the feeling of being a burden on others may be a particularly important marker for suicide risk in college students. Similarly, as expected, thwarted belongingness was found to be significantly and positively associated with suicide proneness. Again, this result is in line with previous work (e.g., Brown et al., 2009; Van Orden, Witte, James, et al., 2008) investigating thwarted belongingness as a risk factor for suicidality in university students. Given that people’s perceptions of social support and interconnections with others are well-documented protective factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (You et al., 2011), it should be expected that the unmet need to belong contributes to suicidality. In sum, the findings that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are both significantly associated with suicide proneness in the present study further supports the central component of Joiner’s (2005) theory and suggests that the measurement of these interpersonal constructs may aid clinicians in the task of suicide risk assessment.

Consistent with the fourth hypothesis, perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness both emerged as significant mediators in the relation between alcohol-related problems and suicide proneness. Regarding perceived burdensomeness, this finding provides support for the proposed mediational model and suggests that individuals who are experiencing alcohol-related problems may be more prone to suicide in part from perceptions of being a burden on others. For example, a college student who is caught driving under the influence of alcohol may not only face legal penalties, but may also be forced to ask his/her parent’s for money in order to pay the associated fines, which may increase the likelihood of developing perceptions of burdensomeness. These feelings of being a burden on others, in turn, may increase the risk of suicide. It should be noted that negative consequences from alcohol are not always associated with feelings of burdensomeness; however, given that students often remain financially and emotionally dependent on their parents, especially during their first two years of college, they may be at an elevated risk of perceiving themselves as a burden on loved ones after encountering a problem due to their alcohol use. Joiner (2005) asserted that perceived burdensomeness is actually a misperception, a cognitive distortion precipitated by the individual’s internal attributions of ineffectiveness and incompetence. Therefore, these erroneous thoughts of burdensomeness in college students may be particularly amenable to cognitive therapy interventions which challenge distorted thinking and elicit more realistic thoughts and appraisals in order to reduce suicide risk. Treatment research in this area is the necessary next step to ascertain the effectiveness of psychotherapy targeting perceived burdensomeness among college students who may be experiencing alcohol-related problems.

In line with the second part of the fourth hypothesis, thwarted belongingness also mediated the relation between alcohol-related problems and suicide proneness. As expected, students who reported alcohol-related problems experienced a diminished sense of belonging often resulting in higher levels of suicide proneness. This finding is consistent with others (e.g., Conner et al., 2007; You et al., 2010) who have demonstrated that belongingness as an important protective factor against suicidal behaviors among individuals with substance use disorders. Thus, our results provide additional empirical support for Joiner’s theory (2005) and its applicability to alcohol using college students. Future researchers should test the proposed meditational model in individuals who are in treatment for alcohol abuse in order to establish the associations among the study variables in this high risk population.

The results supported our hypothesis that the mediation via perceived burdensomeness would be significantly stronger than the mediation via thwarted belongingness. One interpretation of this finding is that college students often have many opportunities to develop and maintain quality relationships. These meaningful interpersonal connections with others may form in places such as fraternities, sororities, intramural sports teams, and classrooms. Thus, thwarted belongingness may not be as important in the alcohol-related problems-suicide proneness link for college students. Moreover, students who are encountering alcohol-related problems may be part of a group of peers who are also experiencing negative consequences relating to alcohol, so belonging to a group in this context may serve as a protective factor against suicidality. On the other hand, perceived burdensomeness may play a larger role in the relation between alcohol-related problems and suicide proneness in college students. College students are often dependent on their parents financially and emotionally. Accordingly, students may feel as if they are a burden on their family if they experience a problem due to their alcohol use such as losing an academic scholarship, being arrested, having an argument of fight with a family member, or repeatedly asking for money to pay for alcohol. Given that one’s perception of being a burden on his or her genetic relatives is especially relevant to suicidality (Brown et al., 2009; DeCatanzaro, 1995), college students may be particularly affected psychologically following an experience with alcohol-related problems, which may result in an increased risk for suicide.

Our findings should be considered within the context of the study’s limitations. First, the sample consisted predominantly of young adult European-American college students. It is important to use caution when generalizing these results to other populations, such as older students and minorities. Replication of these results across samples and populations are encouraged. Second, overall, the participants had experienced few interpersonal problems (i.e., burdensomeness, belongingness) limiting the ability to generalize these findings to other groups. Future investigation in this area would benefit from research efforts examining these variables in a range of samples including clinical and geriatric populations. Third, there may be several other possible mediators that could help account for the obtained relation between alcohol-related problems and suicide proneness. Variables to consider in future research might include impulsivity, depression, and hopelessness. Fourth, participants were asked to report on alcohol-related problems that occurred within the past year, which, given the large proportion of freshmen in our sample, could have happened while they were still in high school. Future researchers should consider a timeline for asking the target population when certain behaviors may have occurred and inquire about these behaviors accordingly. Last and perhaps most importantly, this study relied exclusively on data collected using a cross-sectional research design. One assumption of mediation is a sequencing of variables such that the outcome does not cause the predictor or the mediator, nor does the mediator cause the predictor (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The methodology used to collect these data precludes a causal interpretation of associations among variables. More sophisticated methodologies and longitudinal designs should be employed before causal inferences can be made regarding the directional and developmental pathways that connect these variables in college women.

In spite of these limitations, the current findings along with the work of others (e.g., Joiner et al., 2009; Pedersen, 2008; Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, et al., 2008) suggest that the assessment of alcohol-related problems, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness could potentially aid in the prediction of suicide proneness. Moreover, our results add to the existing literature by indicating that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are significant mediators in the link between alcohol-related problems and suicide proneness in college students. The obtained findings suggest that it would be advisable for clinicians to be aware of students’ experiences with alcohol-related problems in conjunction with levels of burdensomeness and belongingness when assessing for suicide risk. In addition to assessment, prevention efforts which target these identified risk factors for suicidality should be developed and implemented on college campuses.

References

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The truth about suicide. New York: American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.afsp.org/files/College_Film//factsheets.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Arria A, O’Grady K, Caldeira K, Vincent K, Wilcox H, Wish E. Suicide ideation among college students: A multivariate analysis. Archives of Suicide Research. 2009;13:230–246. doi: 10.1080/13811110903044351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R, Leary M. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Brown SL, Johnson A, Olsen B, Melver K, Sullivan M. Empirical support for an evolutionary model of self-destructive motivation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2009;39:1–12. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQUARS) [online] National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Britton PC, Sworts LM, Joiner TE. Suicide attempts among individuals with opiate dependence: The critical role of belonging. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1395–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Hosier SG, Crossley S, Kendall B, Roberts KL. Motives for drinking, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related problems among British secondary-school and university students. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:2147–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson CL, Wingate LR, Rasmussen KA, Slish ML. Hope as a predictor of interpersonal suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2009;39:499–507. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCatanzaro D. Reproductive status, family interactions, and suicidal ideation: Surveys of the general public and high risk groups. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1995;16:385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Kivlahan DR, Doyle SR, Longabaugh R, Greenfield SF. Concurrent validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and AUDIT zones in defining levels of severity among out-patients with alcohol dependence in the COMBINE study. Addiction. 2006;101:1696–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drum DJ, Brownson C, Denmark A, Smith SE. New data on the nature of suicidal crises in college students: Shifting the paradigm. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. 2009;40:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Blasey CM, Mitchell S. Adult attachment, emotional distress, and interpersonal problems in alcohol and drug dependency treatment. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;24:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis TE, Rutherford B. Cognition and suicide: Two decades of progress. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008;1:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Freedenthal S, Lamis DA, Osman A, Kahlo D, Gutierrez PM. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-12 in samples of men and women. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67:609–623. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlow SJ. Age, gender, and ethnicity differences in patterns of cocaine and ethanol use preceding suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:615–619. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez V, Bradizza C, Collins R. Drinking to cope as a statistical mediator in the relationship between suicidal ideation and alcohol outcomes among underage college drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/a0015543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills A, Afifi T, Cox B, Bienvenu O, Sareen J. Externalizing psychopathology and risk for suicide attempt: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2009;197:293–297. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a206e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Pettit J, Walker R, Voelz Z, Cruz J, Rudd M, et al. Perceived burdensomeness and suicidality: Two studies on the suicide notes of those attempting and those completing suicide. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2002;21:531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Van Orden K, Witte T, Selby E, Ribeiro J, Lewis R, et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow N, Thompson M, Okun A, Price A, Young S, Bender M, et al. Risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in abused African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:311–319. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamis DA, Ellis JB, Chumney FL, Dula CS. Reasons for living and alcohol use among college students. Death Studies. 2009;33:277–286. doi: 10.1080/07481180802672017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamis DA, Malone PS, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Intimate partner psychological aggression and suicide proneness in college women: Alcohol related problems as a potential mediator. Partner Abuse. 2010;1:169–185. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.1.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamis DA, Malone PS, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Ellis TE. Body investment, depression, and alcohol use as risk factors for suicide proneness in college students. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2010;31:118–127. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Arata C, Bowers D, O’Brien N, Morgan A. Suicidal behavior, negative affect, gender, and self-reported delinquency in college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:255–266. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.3.255.42773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Lamis DA. Current suicide proneness and past suicidal behavior in adjudicated adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:415–426. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Friend J, Powell A. Adolescent suicide, gender, and culture: A rate and risk factor analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:402–414. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Langford R, Rohde P, Seeley J, Chapman J. The Life Attitudes Schedule: A scale to assess adolescent life-enhancing and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1995;25:458–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Rohde P, Langford RA. Attitudes Schedule (LAS): A risk assessment for suicidal and life-threatening Behaviors Technical Manual. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Marzell M, Varvil-Weld L, Turrisi R, Guttman K, Abar C. Onetime or repeat offenders? An examination of the patterns of alcohol-related consequences experienced by college students across the freshman year. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:508–511. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Teti LO, Lawrence BA, Weiss HB. Alcohol involvement in hospital-admitted nonfatal suicide acts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40:492–499. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.5.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miotto PP, Preti AA. Suicide ideation and social desirability among school-aged young people. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31:519–533. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide, v.6.1. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen WW. Does cannabis use lead to depression and suicidal behaviours? A population-based longitudinal study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;118:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss U, Schuckit M, Smith L, Danko G, Buckman K, Bierut L, et al. Comparison of 3190 alcohol-dependent individuals with and without suicide attempts. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor JH, Hurtado S, DeAngelo L, Palucki Blake L, Tran S. The American freshman: National norms fall 2010. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;38:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Langford R. Life Attitudes Schedule: Short Form (LAS-SF): A risk assessment for suicidal and life-threatening behaviors [Technical Manual] Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Seeley J, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Rohling M. The Life Attitudes Schedule-Short Form: Psychometric properties and correlates of adolescent suicide proneness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:249–260. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.3.249.23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer M, Jeglic EL, Stanley B. The relationship between suicidal behavior, ideation, and binge drinking among college students. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12:124–132. doi: 10.1080/13811110701857111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. Alcoholism and suicidal behavior: A clinical overview. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Heppner MJ. Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites Scale (PCRW): Construction and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson H, Pena-Shaff J, Quirk P. Predictors of college student suicidal ideation: Gender differences. College Student Journal. 2006;40:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2009. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434. [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Beck KH. The social context of four adolescent drinking patterns. Health Education Research. 1994;9:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden K, Witte T, Cukrowicz K, Braithwaite S, Selby E, Joiner T. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE., Jr Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden K, Witte T, James L, Castro Y, Gordon K, Braithwaite S, et al. Suicidal ideation in college students varies across semesters: The mediating role of belongingness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:427–435. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle R. Alcohol problems in adolescents and young adults: Epidemiology, neurobiology, prevention, and treatment. New York, NY US: Springer Science; 2006. Alcohol consumption and its consequences among adolescents and young adults; pp. 67–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wines J, Saitz R, Horton N, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet J. Suicidal behavior, drug use and depressive symptoms after detoxification: A 2-year prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:S21–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You S, Van Orden KA, Conner KR. Social connections and suicidal thoughts and behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:180–184. doi: 10.1037/a0020936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]