Abstract

Quantifying sweat gland activation provides important information when explaining differences in sweat rate between populations and physiological conditions. However, no standard technique has been proposed to measure sweat gland activation, while the reliability of sweat gland activation measurements is unknown. We examined the interrater and internal reliability of the modified-iodine paper technique, as well as compared computer-aided analysis to manual counts of sweat gland activation. Iodine-impregnated paper was pressed against the skin of 35 participants in whom sweating was elicited by exercise in the heat or infusion of methylcholine. The number of active glands was subsequently determined by computer-aided analysis. In total, 382 measurements were used to evaluate: 1) agreement between computer analysis and manual counts; 2) the interrater reliability of computer analysis between independent investigators; and 3) the internal reliability of sweat gland activation measurements between duplicate samples. The number of glands identified with computer analysis did not differ from manual counts (68 ± 29 vs. 72 ± 24 glands/cm2; P = 0.27). These measures were highly correlated (r = 0.77) with a mean bias ± limits of agreement of −4 ± 38 glands/cm2. When comparing computer analysis measures between investigators, values were highly correlated (r = 0.95; P < 0.001) and the mean bias ± limits of agreement was 4 ± 18 glands/cm2. Finally, duplicate measures of sweat gland activation were highly correlated (r = 0.88; P < 0.001) with a mean bias ± limits of agreement of 3 ± 29 glands/cm2. These results favor the use of the modified-iodine paper technique with computer-aided analysis as a standard technique to reliably evaluate the number of active sweat glands.

Keywords: heat-activated sweat glands, heat loss, sweat rate, sweat output, thermoregulation

sweat production from eccrine glands is arguably the most important effector mechanism involved in human temperature regulation during heat stress. It is therefore not surprising that normal sweat rate responses have been thoroughly characterized at rest and during exercise (25, 27, 30, 40), with many investigations examining how sweat production differs between populations (3, 20, 22, 33, 41), as well as with various physiological (23, 28, 38) and disease (24) states. Furthermore, recent work has established a valid method to assess the physiological control of sweating (9), as well as examine its normal biological variation (19).

Sweat is produced by 2–4 million eccrine sweat glands dispersed over the nonglabrous skin regions of the human body (34, 35). As such, total sweat production is determined by both the number of activated glands, as well as the output per individual gland (7, 25). Assessments of sweat gland activation have been used clinically to evaluate the extent of neurological damage caused by various disease states (13), as well as experimentally to evaluate sweat gland function in relation to exercise intensity (26), exercise training (8, 12), age (2, 14–17, 21, 39), obesity (5), and sex (5, 11, 18, 29). Importantly, the number of active sweat glands has also been used to determine whether differences in sweat rate between populations/conditions are mediated via central or peripheral mechanisms (36, 37).

To date, experimental assessments of sweat gland function have been achieved through a variety of techniques, including the starch-iodine technique (12, 15–18, 25, 26, 29, 39), the modified iodine-paper technique (5, 8, 11, 36, 37), and the macrophotographic technique (2, 21). Briefly, the starch-iodine technique consists of painting the skin surface with iodine and subsequently applying starch paper. The modified iodine-paper technique consists of applying iodine-impregnated paper onto the surface of unpainted skin. In both cases, the active sweat glands produce identifiable blue dots on the starch/iodine-impregnated paper. In contrast, the macrophotographic technique consists of painting the skin with Vaseline to promote beading of sweat while a series of pictures are taken from the measurement area. Common to all techniques is that the number of active sweat glands is subsequently counted manually, the count typically performed by the same experienced investigator.

Given the valuable information provided by measurements of sweat gland activation, it is surprising that no standard technique has been advocated to experimentally determine the number of active sweat glands. Considering that multiple laboratories utilize various techniques to achieve a common objective, the use of a standard technique would provide measurement consistency and allow direct comparisons between laboratories. Furthermore, interrater reliability of measuring the number of active sweat glands has not been examined. Since determining the number of active sweat glands within a collected sample is most often achieved though manual counts, it is unknown whether the number of active sweat glands determined by one investigator can reliably be interpreted by other external laboratories. With these issues in mind, we sought to evaluate the modified iodine-paper technique, in combination with a free, publicly available computer program (ImageJ), to count the number of active sweat glands. Specifically, we investigated 1) the agreement between computer-assisted and manual counts of active sweat glands; and 2) whether computer-assisted analysis is reliable between investigators from independent laboratories. Furthermore, we were interested in using the modified iodine-technique to determine the internal reliability of duplicate active sweat gland measurements. We hypothesized that the modified iodine-paper technique with computer-assisted analysis would provide a standardized and reliable means of determining the number of active sweat glands.

METHODS

Ethical Approval

The experimental protocol was approved by the University of Ottawa Health Sciences and Science Research Ethics Board, as well as the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers before their participation in the study.

Subjects

The subjects consisted of 35 volunteers (13 females). All subjects were healthy, nonsmoking, and free of any known cardiovascular, metabolic, and respiratory diseases. The subjects had a mean ± SD age of 34 ± 11 yr, body height of 172 ± 11 cm, and body mass of 78.1 ± 16.9 kg.

Experimental Design

Study 1.

Subjects were part of a larger study examining sex-related differences in temperature regulation. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the subject changed into shorts and sandals (as well as a sports bra for female subjects) and sat quietly for a 60-min instrumentation period at an ambient room temperature of ∼24°C. Following instrumentation, the subject was transferred to an environmental chamber regulated to an ambient air temperature of 40°C and a relative humidity of 20%. A fan was placed in front of the subject to provide an airflow of ∼1 ml/s. The subject, seated in the upright position, rested for a 30-min baseline period. Subsequently, the subject performed in succession three 30-min exercise periods at fixed rates of metabolic heat production equal to 200, 250, and 300 W/m2. The number of active sweat glands on the upper back, chest, and forearm was determined in duplicate at 30, 60, and 90 min of exercise using the technique described below. The measurements for the back were performed on the upper trapezius muscle, ∼5 cm medial from the acromion; for the chest on the pectoralis major muscle, ∼5 cm below the clavicle; and for the forearm on the dorsal side, at the greatest circumference determined visually.

Study 2.

Subjects were part of a larger study investigating the effect of heat acclimation on skin-grafted individuals compared with controls. Two intradermal microdialysis probes, consisting of two reinforced sections of polyimide tubing connected by a 1-cm dialysis membrane (Bio-analytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN), were inserted into healthy, noninjured skin by advancing a 25-gauge needle 15–20 mm through the dermal layer, followed by threading the microdialysis probe through the lumen of the needle and withdrawing the needle. Microdialysis probes were perfused with lactated Ringer solution (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) at a rate of 2 μl/min via a perfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) while hyperemia associated with insertion trauma subsided (a minimum of 90 min). At each site, dose-response curves for sweating were assessed upon administration of increasing doses of methylcholine (1 × 10−7 M to 1 M at 10-fold increments). Each dose was administered for 5 min at a perfusion rate of 2 μl/min. The highest dose (i.e., 1 M) was continually administered until a maximum plateau in sweating occurred (∼20–30 min) after which the ventilated capsule used to measure sweat rate was removed and sweat gland activation was determined in duplicate using the technique described below. This experimental protocol was performed before and following 7 days of heat acclimation.

Measurement of Sweat Gland Activation

For both studies, the number of active sweat glands was determined using the modified iodine-paper technique originally proposed and validated by Randall (31, 32) and subsequently modified by Davis et al. (10). Four to five days before an experimental session, pieces of 100% cotton paper (32 lb; Southworth, Agawam, MA) were cut to a predetermined size (9 cm2 in study 1; 2.83 cm2 in study 2) and placed in a sealed container containing iodine in solid form (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Each piece of cotton paper was supported to avoid direct contact with the iodine. After ∼48 h, the pieces of paper became saturated with iodine (as indicated by their dark brown color) and were subsequently transferred to a sealed bag for use during the experimental protocol. To ensure a uniform application on the skin surface, double-sided tape was used to affix the cotton paper to a flat hard plastic surface. Before the application of the cotton paper the skin was blotted dry, following which the cotton paper was firmly pressed against the skin surface for a period of ∼5 s. With the use of this technique, sweat excreted from the active sweat glands forms easily identifiable blue dots on the iodine-impregnated paper when it is placed in contact with the skin surface. After the paper was removed from the skin, it was immediately scanned at high resolution (600 dots/in.) using a commercially available scanner for subsequent analysis using the ImageJ image processing and analysis program (1).

Image processing and analysis.

ImageJ is a public domain Java image processing and analysis program that can be downloaded for free (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html, last accessed November 20 2011) on any operating system. ImageJ is particularly useful for determining the number of active sweat glands, as it can easily identify the number of individual particles from a scanned image. The reader is referred to the appendix for step-by-step instructions on how to analyze sweat gland activation samples. It is important to note that the analysis requires the investigator to define a lower and upper size limit for the pixel area, which is the minimum/maximum size allowable for a dot to be considered in the count. In the current study, the investigators were allowed to choose the limits they deemed appropriate to ensure that all sweat glands were included within the count. Once the analysis performed, the software generates a count of the particles present in the image, which is the number of active glands for that sample (see Fig. 1). The number of glands is then divided by the surface area of the paper to give a value of active sweat glands per square centimeter.

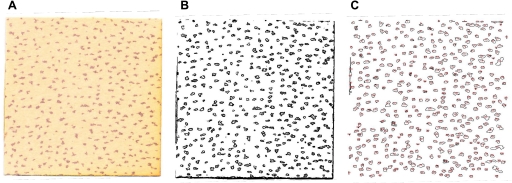

Fig. 1.

Number of active sweat glands is determined by pressing a piece of cotton paper saturated with iodine onto the skin surface (A). Sample is subsequently scanned at high resolution and analyzed with ImageJ software, where the image is converted to black and white (B). Number of active sweat glands is subsequently counted, with each individual count being outlined by the software (C).

Data Analyses

The following terms were used to describe comparisons made in the current study: 1) agreement: variability in sweat gland activation measurements between computer-assisted analysis and manual counts; 2) interrater reliability: the variability in sweat gland activation counts as determined by computer-assisted analysis between independent investigators; and 3) internal reliability: the variability of duplicate sweat gland activation measurements (determined using computer-assisted analysis).

A wide range of sweat gland activation measures were obtained by combining data from study 1 and study 2 and analyzed as one data set to answer the following questions: 1) is there good agreement between computer software and manual analyses when determining the number of active sweat glands?; and 2) is computer-assisted analysis reliable between two independent investigators (i.e., interrater reliability)? Furthermore, we examined the internal reliability of the modified iodine-paper technique by analyzing duplicate sweat gland activation measurements obtained from the same subject at the same site via computer-assisted analysis. To address the agreement between computer analysis and manual counts (question 1), 50 random samples from each study (100 total) were chosen by investigator 1 and presented to investigator 2, who analyzed each image through computer analysis and manually. Manual counts were performed by printing an enlarged version of the scanned image of the sample, and each gland was manually circled with a pen. To address interrater reliability of computer analysis between two independent investigators (question 2), all images from both data sets were independently analyzed by each investigator. Similarly, to determine the internal reliability of the modified iodine-paper technique, duplicate measurements obtained from a given subject at a given time point were analyzed independently by each investigator using computer-assisted analysis. For all analyses, the investigators were blinded to the experimental condition, time point, and location at which the image was obtained.

Statistical Analyses

Based on the recommendations by Atkinson and Nevill (4), we used a range of statistical methods to assess the modified-iodine paper technique with computer-assisted analysis. For each question, differences between analysis techniques (computer-assisted vs. manual) as well as between investigators (investigator 1 vs. investigator 2) were compared with independent sample t-tests, Bland-Altman plots, Pearson-Product moment correlations, and coefficients of variation. Bland-Altman plots were constructed by calculating mean bias and limits of agreement (6). The difference between measures (i.e., counts), with a 95% probability, will lie within the respective limits of agreement of these plots. Limits of agreement were calculated by multiplying the standard deviation of the mean difference between analysis technique/investigators by two (4). Furthermore, we included qualitative limits of magnitude based on the largest differences in sweat gland activation between populations reported in the literature (5, 14) (limit 1: +50 glands/cm2 and limit 2: −25 glands/cm2). Because the total number of activated sweat glands varied between subjects and between studies, the coefficient of variation was calculated to provide an index of relative differences independent of total glands present. The coefficient of variation was calculated for each comparative count and then averaged together to provide an overall coefficient of variation for each research question. The smallest change worth detecting with the current method was calculated using the formula: 1.96 × × SE, where SE stands for standard error of measurement, which itself was calculated using the formula: SD × where SD stands for standard deviation and ICC for intraclass correlation coefficient of duplicate measurements. SigmaPlot 12.0 and Microsoft Excel 2010 were used for all analyses. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests. Data are reported as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

There was a wide range of sweat gland activation within the images analyzed. The number of glands activated pharmacologically averaged 59 glands/cm2, with a SD of 17 glands/cm2. The minimum number of glands activated pharmacologically was 22 glands/cm2, while the maximum was 99 glands/cm2. During exercise in the heat, average sweat gland activation was 81 glands/cm2, with a SD of 30 glands/cm2. The minimum number of glands activated during exercise was 35 glands/cm2, with the maximum observed being 187 glands/cm2. As such, the images analyzed provided a good range of sweat gland activation values with which to assess the modified iodine-paper technique with computer-assisted analysis.

Is There Good Agreement Between Computer and Manual Analysis?

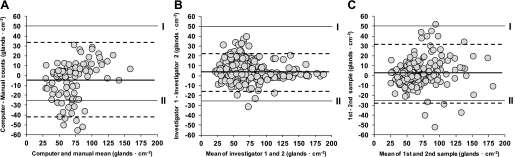

One-hundred samples were included in the analysis. The number of glands identified with computer-aided analysis (68 ± 29 glands/cm2) did not significantly differ from manual counts (72 ± 24 glands/cm2; P = 0.27). The coefficient of variation between manual and computer-assisted counts was 16 ± 15%. The two methods were highly correlated (r = 0.77; P < 0.001) and the mean bias ± limits of agreement (computer − manual) was −4 ± 38 glands/cm2, with 86% (86 out of 100) of individual differences falling within the qualitative limits of magnitude (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Bland-Altman plot of intermethod (computer vs. manual analysis; A), interinvestigator (investigator 1 vs. 2; B), and internal (sample 1 vs. 2; C) differences in the number of active sweat glands. Circles represent an individual count of active sweat glands (A: n = 100; B: n = 382; C: n = 167). In A–C, the bold solid line represents the mean bias, while the dashed lines represent the limits of agreement. Roman numerals represent the largest range of reported differences in sweat gland activation.

Is Computer-Assisted Analysis Reliable Between Two Independent Investigators?

Three-hundred eighty-two samples were included in the analysis. With the use of computer-assisted analysis, the number of glands identified by investigator 1 (74 ± 28 glands/cm2) did not differ significantly from investigator 2 (70 ± 30 glands/cm2; P = 0.07). The coefficient of variation between the two investigators was 7 ± 10%. Counts from both laboratories were highly correlated (r = 0.95; P < 0.001), and the mean bias ± limits of agreement (analyzer 1 − analyzer 2) was 4 ± 18 glands/cm2, with 99% of individual differences (381 out of 382) falling within the qualitative limits of magnitude (Fig. 2B).

What Is the Internal Reliability of the Modified Iodine-Paper Technique?

One-hundred sixty-seven sequential samples were included in the analysis. When duplicate measures were analyzed using computer-assisted analysis, the number of glands in the first sample (73 ± 31 glands/cm2) did not significantly differ from the second sample (71 ± 29 glands/cm2; P = 0.37). The coefficient of variation between samples was 11 ± 10%. Sweat gland counts from duplicate samples were highly correlated (r = 0.88; P < 0.001), and the mean bias ± limits of agreement (sample 1 − sample 2) was 3 ± 29 glands/cm2, with 96% (161 out of 167) of individual differences falling within the qualitative limits of magnitude (Fig. 2C). The smallest detectable change calculated from duplicate measurements was 30 glands/cm2.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined the agreement between computer-assisted analysis and manual counts of sweat gland activation, the interrater reliability of computer-assisted analysis, as well as the internal reliability of the modified iodine-paper technique. The results demonstrate that computer-assisted counts of active sweat glands show good agreement compared with manual analysis. Further, the number of active sweat glands determined using computer-assisted analysis shows little variability between independent investigators (interrater), as well as between duplicate measurements (internal). Combined with its ease of use, we propose that the modified iodine-paper technique with computer-assisted analysis provides a simple and reliable determination of the number of active sweat glands.

Before the current study, no standard technique to measure sweat gland activation had been advocated. This has led to the use of a variety of techniques, making comparisons difficult and possibly limiting interpretations between different laboratories. Furthermore, no study has specifically examined whether determining the number of active sweat glands is reliable between independent investigators. In the current study, we chose to examine the reliability of the modified iodine-paper technique, with computer-assisted analysis, due in large part to its ease of use and minimal time required for analysis. By examining the reliability of this technique, we were interested in determining whether it could be used as a standard technique to determine the number of active sweat glands.

Is There Good Agreement Between Computer and Manual Analysis?

Computer-determined counts of active sweat glands closely agreed with those obtained by manual count. This was evidenced by a strong correlation and small coefficient of variation between the two methods. Further, the bias and limits of agreement were relatively small between the two methods and fell within the upper and lower ranges of reported differences in the literature (see Fig. 2A). Although the modified-iodine paper technique has previously been validated (31, 32) and used in a number of publications (5, 8, 11, 36, 37), the use of computer-assisted analysis has never been compared with manual counts. It is therefore interesting to compare the counts obtained in the current study with those reported in the literature. The number of active sweat glands measured using the current modified iodine-paper technique provided similar values to those reported in previous studies where manual counts were performed. Specifically, the reported number of active sweat glands during exercise range from ∼80 glands/cm2 during low (35% V̇o2 max) to ∼120 glands/cm2 during moderate (65% V̇o2 max) intensity exercise in normal ambient conditions (25–30°C, 40–50% relative humidity) and up to over 150 glands/cm2 during moderate intensity exercise in a hot (35–49°C, 30–80% relative humidity) environment (12, 25, 26, 29). Similarly, the number of active sweat glands during pharmacologically induced sweating range from ∼60 to 120 glands/cm2 (10, 16). These values resemble the number of active sweat glands measured in the current data set during exercise in the heat (81 ± 30; range of 35–137 glands/cm2) and pharmacological stimulation (59 ± 12; range of 22–99 glands/cm2).

Is Computer-Assisted Analysis Reliable Between Two Independent Investigators?

The use of computer-assisted analysis adds a layer of objectivity to the determination of the number of active sweat glands for a given sample. When manually counting the number of sweat glands, the investigator must subjectively determine dots that actually constitute a single sweat gland vs. those that may have converged due to a high output from multiple glands. In contrast, the use of computer software allows the user to define a lower and upper size limit for the pixel area, which is the minimum/maximum size allowable for a dot to be considered in the count. It is important to note that using a fixed pixel range has the potential to reduce all subjectivity associated with the determination of what constitutes a gland or not when analyzing multiple samples. However, this approach assumes that the sweat glands from all collected samples will be of the same size. This may very well occur when measurements are taken from a given anatomical location during a repeated measures design experiment (e.g., pre- to postacclimation on the forearm). In the current study, however, the use of a fixed pixel range limit was deemed inappropriate as the anatomical locations (e.g., back vs. forearm) and populations (males vs. females) from which the samples were obtained resulted in different gland sizes on the collected samples. Consequently, the investigators freely adjusted the upper and lower pixel size limits based on a subjective interpretation of what should be considered a sweat gland or not. However, adjusting the upper and lower size limits does add subjectivity to the computer-aided analysis, which led us to examine interrater reliability. Even though the investigators were allowed to determine the pixel area limits, and therefore the size of dots that would be considered a gland or not, there was little interrater variability for individual counts. There was a very high correlation between analyzers (r = 0.95), and the mean bias between investigators was only 4 glands/cm2, with all but one individual difference falling inside the limits of magnitude (see Fig. 2B). These results favor the use of computer-assisted analysis as a standard procedure to determine the number of active sweat glands between independent laboratories.

What Is the Internal Reliability of The Modified Iodine-Paper Technique?

The results from the current study suggest there is some variability between duplicate measurements, although with no evident systematic bias between the first and second measurements (Fig. 2C). It is important to note that the variability in the number of active sweat glands over duplicate measurements was due to variability in the modified iodine-paper technique itself, as the counts were performed by computer-assisted analysis. To our knowledge, no study has specifically examined the internal reliability of determining the number of active sweat glands, regardless of the method employed. However, Buono and Sjoholm (8) did report a 5% coefficient of intrasubject variation when using the modified-iodine paper technique combined with manual analysis. In contrast, we report an intrasubject coefficient of variation of 11 ± 10%. Furthermore, the smallest difference worth detecting calculated from duplicate measurements was 30 glands/cm2, suggesting that differences in sweat gland activation of less than ∼30 glands/cm2 using the current method may not be worth considering (i.e., differences within the error of the measurement). Together, these values provide a basis to determine whether observed differences in sweat gland activation should be interpreted as meaningful when using the evaluated techniques. It is interesting to note that the calculated smallest detectable change is consistent with previous studies (5, 8, 14, 18, 26) reporting significant differences in sweat gland activation between various populations and/or experimental conditions. Duplicate measures were also highly correlated (r = 0.88; P < 0.001) and the mean bias ± limits of agreement (sample 1 − sample 2) was 3 ± 29 glands/cm2, with the vast majority of individual differences falling within the limits of magnitude (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that the modified-iodine paper technique with computer-assisted analysis is sensitive enough to detect typical changes in sweat gland activation.

Perspectives

The use of standard measurement techniques and analytical tools is important to ensure consistency and allow for more direct comparisons between independent laboratories. In the current study, we used the modified iodine-paper technique due to its ease of use and minimal need of equipment. It also allows for a rapid determination of the number of active sweat glands and thus multiple measurements at a given time period, as opposed to relying on a single sample. While we did not compare the current method with those of previous studies (e.g., starch-iodine and macrophotographic), the results of the current study provide a strong basis for advocating the use of the modified-iodine paper technique combined with computer-assisted analysis for the standard determination of sweat gland activation. First, computer-assisted counts of the number of active sweat glands show good agreement with those obtained manually. The advantages of computer-assisted analysis are that it provides a more objective count of the number of active sweat glands, and the analysis of a sample is done within minutes, as opposed to longer periods of time required for manual analysis. Second, computer-assisted analysis is reliable between two investigators from independent laboratories. This ensures that the counts obtained in one laboratory can be reliably replicated in another, making comparisons between different laboratories more direct and meaningful. Third, the measurement technique itself shows little variability between duplicate measures, resulting in relatively low values of measurement noise and of smallest detectable difference. As such, small differences in sweat gland activation between populations and/or experimental conditions can be identified.

Conclusion

The current study examined the modified iodine-paper technique with computer-assisted analysis for the simple and reliable determination of sweat gland activation. Computer-assisted counts of active glands showed good agreement compared with commonly used manual counts. Furthermore, computer-assisted determination of active sweat glands showed little interrater variability. Finally, we examined the internal reliability of duplicate measurements of sweat gland activation, which fell within the range of previously reported differences. Based on the observed results, we propose that the modified-iodine paper technique with computer-assisted analysis be employed as a standard measurement of sweat gland activation.

GRANTS

The current work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN-298159-2009), Leaders Opportunity Fund from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (22529), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM-068865. G. P. Kenny is supported by a University of Ottawa Research Chair in Environmental Physiology.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.G., M.S.G., R.A.L., J.P., C.G.C., and G.P.K. conception and design of research; D.G., M.S.G., R.A.L., and J.P. performed experiments; D.G. and M.S.G. analyzed data; D.G., M.S.G., R.A.L., J.P., C.G.C., and G.P.K. interpreted results of experiments; D.G. and M.S.G. prepared figures; D.G. and M.S.G. drafted manuscript; D.G., M.S.G., R.A.L., J.P., C.G.C., and G.P.K. edited and revised manuscript; D.G., M.S.G., R.A.L., J.P., C.G.C., and G.P.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brendan Swift, Kimberly Hubing, and Jena Langlois for assistance during data collection.

APPENDIX

Using ImageJ to Count the Number of Active Sweat Glands

Step 1) to analyze a sample, determine the edges of the scanned image using the “Find edges” option (Process toolbar–Find edges).

Step 2) next, set the image type to 8-bit grayscale (Image toolbar–Type–8-bit) before converting the image to a binary (black and white) image (Process toolbar–Binary–Make binary). Once this step is complete, the dots produced by the active glands are displayed in black, with the background being white.

Step 3) to perform a count of the number of active glands, select the “Analyze particles” (Analyze toolbar–Analyze particles) and first define a lower and upper size limit for the pixel area, which is the minimum/maximum size allowable for a dot to be considered in the count. Before running the analysis, ensure that the following options are chosen: display results, clear results, exclude on edges, record starts. Also, ensure that the “Outlines” option is selected under the “Show” menu to visually examine which particles have been included by the software during the analysis.

Step 4) once the analysis performed, the software generates a count of the particles present in the image, which is the number of active glands for that sample. It also provides an image in which each individual count included in the analysis has been circled in red. If the number of particles included in the analysis is inadequate, return to step 3 and adjust the lower and upper size limit of the pixel area accordingly.

Step 5) the number of particles is divided by the surface area of the paper to give a value of active sweat glands per square centimeter.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abramoff MD, Magalhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophot Intl 11: 36–42, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson RK, Kenney WL. Effect of age on heat-activated sweat gland density and flow during exercise in dry heat. J Appl Physiol 63: 1089–1094, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. Effects of training, environment, and host factors on the sweating response to exercise. Int J Sports Med 19: 103–105, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med 26: 217–238, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bar-Or O, Lundegren HM, Magnusson LI, Buskirk ER. Distribution of heat-activated sweat glands in obese and lean men and women. Hum Biol 40: 235–248, 1968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 8: 307–310, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buono MJ, Connolly KP. Increases in sweat rate during exercise: gland recruitment versus output per gland. J Therm Biol 17: 267–270, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buono MJ, Sjoholm NT. Effect of physical training on peripheral sweat production. J Appl Physiol 65: 811–814, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheuvront SN, Bearden SE, Kenefick RW, Ely BR, Degroot DW, Sawka MN, Montain SJ. A simple and valid method to determine thermoregulatory sweating threshold and sensitivity. J Appl Physiol 107: 69–75, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis SL, Wilson TE, Vener JM, Crandall CG, Petajan JH, White AT. Pilocarpine-induced sweat gland function in individuals with multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol 98: 1740–1744, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frye AJ, Kamon E. Sweating efficiency in acclimated men and women exercising in humid and dry heat. J Appl Physiol 54: 972–977, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ichinose-Kuwahara T, Inoue Y, Iseki Y, Hara S, Ogura Y, Kondo N. Sex differences in the effects of physical training on sweat gland responses during a graded exercise. Exp Physiol 95: 1026–1032, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Illigens BM, Gibbons CH. Sweat testing to evaluate autonomic function. Clin Auton Res 19: 79–87, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inbar O, Morris N, Epstein Y, Gass G. Comparison of thermoregulatory responses to exercise in dry heat among prepubertal boys, young adults and older males. Exp Physiol 89: 691–700, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Inoue Y. Longitudinal effects of age on heat-activated sweat gland density and output in healthy active older men. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 74: 72–77, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Inoue Y, Havenith G, Kenney WL, Loomis JL, Buskirk ER. Exercise- and methylcholine-induced sweating responses in older and younger men: effect of heat acclimation and aerobic fitness. Int J Biometeorol 42: 210–216, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inoue Y, Shibasaki M. Regional differences in age-related decrements of the cutaneous vascular and sweating responses to passive heating. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 74: 78–84, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inoue Y, Tanaka Y, Omori K, Kuwahara T, Ogura Y, Ueda H. Sex- and menstrual cycle-related differences in sweating and cutaneous blood flow in response to passive heat exposure. Eur J Appl Physiol 94: 323–332, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kenefick RW, Cheuvront SN, Elliott LD, Ely BR, Sawka MN. Biological and analytical variation of the human sweating response: implications for study design and analysis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R252–R258, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kenney WL. A review of comparative responses of men and women to heat stress. Environ Res 37: 1–11, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kenney WL, Fowler SR. Methylcholine-activated eccrine sweat gland density and output as a function of age. J Appl Physiol 65: 1082–1086, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kenney WL, Munce TA. Invited review: aging and human temperature regulation. J Appl Physiol 95: 2598–2603, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kenny GP, Journeay WS. Human thermoregulation: separating thermal and nonthermal effects on heat loss. Front Biosci 1: 259–290, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kenny GP, Yardley J, Brown C, Sigal RJ, Jay O. Heat stress in older individuals and patients with common chronic diseases. CMAJ 182: 1053–1060, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kondo N, Shibasaki M, Aoki K, Koga S, Inoue Y, Crandall CG. Function of human eccrine sweat glands during dynamic exercise and passive heat stress. J Appl Physiol 95: 1877–1881, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kondo N, Takano S, Aoki K, Shibasaki M, Tominaga H, Inoue Y. Regional differences in the effect of exercise intensity on thermoregulatory sweating and cutaneous vasodilation. Acta Physiol Scand 164: 71–78, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuno Y. Human Perspiration. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1956 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mekjavic IB, Eiken O. Contribution of thermal and nonthermal factors to the regulation of body temperature in humans. J Appl Physiol 100: 2065–2072, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morimoto T, Slabochova Z, Naman RK, Sargent F. Sex differences in physiological reactions to thermal stress. J Appl Physiol 22: 526–532, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nielsen B, Nielsen M. On the regulation of sweat secretion in exercise. Acta Physiol Scand 64: 314–322, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Randall WC. Quantitation and regional distribution of sweat glands in man. J Clin Invest 25: 761–767, 1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Randall WC. Sweat gland activity and changing patterns of sweat secretion on the skin surface. Am J Physiol 147: 391–398, 1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rowland T. Thermoregulation during exercise in the heat in children: old concepts revisited. J Appl Physiol 105: 718–724, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sato K. The mechanisms of eccrine sweat production. In: Perspectives in Exercise Science and Sports Medicine Volume 6: Exercise, Heat, and Thermoregulation, edited by Gisofi CV, Lamb DR, Nadel ER. Dubuque, IA: WCB Brown and Benchmark, 1993, p. 85–118 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sato K. The physiology, phramacology and biochemistry of the eccrine sweat gland. Rev Physiol Biochem Phramacol 79: 52–131, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sato K, Dobson RL. Regional and individual variations in the function of the human eccrine sweat gland. J Invest Dermatol 54: 443–449, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sato K, Sato F. Individual variations in structure and function of human eccrine sweat gland. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 245: R203–R208, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sawka MN, Latzka WA, Matott RP, Montain SJ. Hydration effects on temperature regulation. Int J Sports Med 19: S108–110, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shibasaki M, Inoue Y, Kondo N, Iwata A. Thermoregulatory responses of prepubertal boys and young men during moderate exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 75: 212–218, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shibasaki M, Wilson TE, Crandall CG. Neural control and mechanisms of eccrine sweating during heat stress and exercise. J Appl Physiol 100: 1692–1701, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor NA. Eccrine sweat glands. Adaptations to physical training and heat acclimation. Sports Med 3: 387–397, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]