Abstract

This study aimed to determine whether 2 wk of high-intensity intermittent training (HIIT) altered inflammatory status in plasma and adipose tissue in overweight and obese males. Twelve participants [mean (SD): age 23.7 (5.2) yr, body mass 91.0 (8.0) kg, body mass index 29.1 (3.1) kg/m2] undertook six HIIT sessions over 2 wk. Resting blood and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue samples were collected and insulin sensitivity determined, pre- and posttraining. Inflammatory proteins were quantified in plasma and adipose tissue. There was a significant decrease in soluble interleukin-6 receptor (sIL-6R; P = 0.050), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1, P = 0.047), and adiponectin (P = 0.041) in plasma posttraining. Plasma IL-6, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-10, and insulin sensitivity did not change. In adipose tissue, IL-6 significantly decreased (P = 0.036) and IL-6R increased (P = 0.037), while adiponectin tended to decrease (P = 0.056), with no change in ICAM-1 posttraining. TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-10 were not detectable in adipose tissue. Adipose tissue homogenates were then resolved using one-dimensional gel electrophoresis, and major changes in the adipose tissue proteome, as a consequence of HIIT, were evaluated. This proteomic approach identified significant reductions in annexin A2 (P = 0.046) and fatty acid synthase (P = 0.016) as a response to HIIT. The present investigation suggests 2 wk of HIIT is sufficient to induce beneficial alterations in the resting inflammatory profile and adipose tissue proteome of an overweight and obese male cohort.

Keywords: exercise training, obesity, cytokines, adipose tissue proteomics, low-grade inflammation

obesity is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation and underpins many long-term debilitating health conditions, including Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (20, 53, 57). The current World Health Organisation (WHO) estimate is that 1.5 billion adults are overweight worldwide, of which over 500 million individuals are obese.

Adipose tissue produces a number of inflammatory cytokines and cell adhesion molecules that contribute to chronic low-grade inflammation. Increased adiposity will drive localized inflammation deriving from cellular hypoxia (64) and macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue (15, 68), which increases the capacity for production of inflammatory proteins. As a consequence, adipose tissue in obese individuals produces greater amounts of inflammatory proteins, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), than lean individuals (11, 29, 32, 33). These inflammatory proteins can be released into the circulation resulting in chronic low-grade inflammation, which is associated with insulin resistance (32).

Exercise has many health benefits, including maintaining a healthy weight, reducing the risk of developing chronic diseases such as T2DM and subsequent CVD (67), and reducing chronic low-grade inflammation in both healthy and disease states (1, 4, 61, 73). In addition, a lifestyle intervention involving exercise has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in individuals with elevated fasting glucose levels, above that of the application of the antihyperglycemic drug metformin (36). Therefore, exercise plays an important role in the prevention of T2DM and associated comorbidities.

Despite adipose tissue being a major source of inflammatory mediators, there is limited research investigating the effects of repeated exercise on inflammatory proteins in adipose tissue. No changes in IL-6, TNF-α, or adiponectin mRNA expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue were found after 12 wk of aerobic training (44) or strength training (34) in obese groups, despite aerobic training causing a significant reduction in body mass. Christiansen and colleagues (16) did, however, find an increase in adiponectin mRNA expression in adipose tissue, in an exercise-only group, but no change in any cytokine mRNA expression. In contrast, lifestyle interventions over 12 wk (16, 17) and 15 wk (12), incorporating exercise and a hypocaloric diet, found a decreased expression of IL-6, TNF-α, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) mRNA in adipose tissue and an increase in adiponectin mRNA alongside a weight loss of 5–14% in obese individuals. Studies investigating protein levels have shown IL-6 to be reduced in adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss induced by a hypocaloric diet (6). Hence the existing literature suggests that exercise alone may not be sufficient to reduce inflammation in adipose tissue.

However, in all of these studies the exercise protocol is of a relatively low to moderate intensity, and more recently studies incorporating elements of high-intensity exercise within an exercise program have been shown to improve cardioprotective outcomes including glucose control and aerobic capacity (for review see 58). This can be achieved with just 2 wk of training of six or seven exercise sessions, with positive training outcomes including improved insulin sensitivity (45). However, this protocol involved four to six 30-s maximal Wingate sprints per session, and participants reported feelings of nausea and light-headedness. An alternate intermittent protocol has shown a marked increase in whole body and skeletal muscle capacity for fatty acid oxidation (60) with 10 longer exercise intervals [∼90% peak oxygen uptake (V̇o2peak)], each lasting 4 min interspersed with 2 min rest in a population of untrained individuals, without any report of the negative outcomes associated with Wingate sprints. In addition to the health benefits associated with intermittent exercise protocols it has also been reported as “more enjoyable” than continuous moderate-intensity exercise in healthy young males (5) and in coronary heart disease patients (26).

To investigate whether increasing the intensity of exercise is sufficient to drive decreases in inflammatory proteins this study examined the effects of 2 wk high-intensity intermittent training (HIIT) on metabolic and inflammatory changes in the circulation and subcutaneous adipose tissue in a cohort of overweight and obese males. Furthermore, the most visually prominent changes in the adipose tissue proteome as a consequence of this exercise training regimen were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twelve overweight and obese males [mean (SD): age 23.7 (5.2) yr (range 18–34 yr); body mass 91.0 (8.0) kg (range 82.3–103.9 kg); body mass index (BMI) 29.1 (3.1) kg/m2 (range 26.0–33.7 kg/m2); waist circumference 96.3 (8.0) cm (range 89.0–112 cm)] participated in this study. All participants had a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 but were otherwise healthy and reported taking part in no more than two bouts of light to moderate intensity exercise per week. Participants were excluded if they smoked or were on any medication. The volunteers gave informed written and verbal consent after being advised of all possible risks and discomforts associated with the procedures used in the study, and all procedures were submitted to and approved by Loughborough University Ethical Advisory Committee.

Preliminary measurements.

Participants performed a V̇o2peak test to volitional exhaustion using a continuous incremental protocol on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur, Groningen, The Netherlands). Expired air was measured continuously for oxygen uptake (V̇o2) using an online breath-by-breath gas analysis system (Ultima CPX, Medical Graphics, MN, USA). V̇o2peak was identified as the highest V̇o2 over a 30-s period during the test. After 7 days, participants attended the laboratory to complete a familiarization of the HIIT. During this visit, participants completed six 4-min bouts of cycling with 2 min of rest between intervals. The workload was manipulated during the trial to ensure that the average corresponding V̇o2 during exercise equated to ∼85% V̇o2peak. Waist-to-hip ratio measurements were also taken during this visit. Waist circumference was measured as half-way between the iliac crest and the lowest rib, and hip circumference was measured at the widest part of the hips according to the procedures outlined by the WHO. Blood pressure was measured using an automated blood pressure monitor (Omron M7, Omron Healthcare, Milton Keynes, UK).

Subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue biopsy and oral glucose tolerance test.

One week after the familiarization, participants attended the laboratory after a 12-h overnight fast (water was allowed). Participants lay in a semisupine position, and 10 ml of 1% (wt/vol) lidocaine was administered under sterile conditions to the lower abdominal area before ∼1.5 g of adipose tissue was extracted ∼10–15 cm laterally to the umbilicus using a percutaneous needle biopsy technique (16). The excised adipose tissue was immediately washed with 0.9% (wt/vol) NaCl solution to limit blood contamination before it was divided into Eppendorfs using sterile forceps. The tissue was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before transferring to a −80°C freezer until required for analysis. A cannula was then inserted into a participant's antecubital vein, and a resting blood sample was collected into K2EDTA vacutainers (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Participants then consumed a 75-g glucose load (82.5 g dextrose monohydrate) in 300 ml liquid within a 5-min period. Further venous blood samples were collected every 30 min over a 2-h period.

HIIT.

Participants completed three sessions of HIIT per week for 2 wk, with 1–2 days rest between each session. Each session consisted of ten 4-min intervals, with expired air collected during the first session to monitor exercise intensity. The mean V̇o2 during the intervals of the first HIIT session was 85.0 (4.6)% V̇o2peak, which equated to 89.5 (2.4)% of maximal heart rate. Subsequently, during the remaining HIIT sessions the workload was kept the same as the first session and heart rate was recorded throughout. The workload was adjusted if heart rate dropped below 80% of maximal levels in the subsequent sessions. Forty-six to forty-eight hours after the last training session a subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsy was taken, a fasted resting blood sample was collected, and an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) undertaken. The posttraining adipose tissue biopsy was taken from the contralateral side of the abdomen. This time delay from the last training session was employed to minimize any influence of acute exercise (28). Fluid and dietary intake were standardized 24 h before both visits. Blood pressure, waist and hip circumference, and V̇o2peak measurements were repeated 72 h after the last training session. All participants were asked to maintain their normal diet and physical activity routine throughout the training period.

Blood preparation.

Hemoglobin concentration was measured in duplicate in whole blood using a commercially available kit (Randox Laboratories, Antrim, UK), and hematocrit content was measured in triplicate with a HaematoSpin1300 centrifuge (Hawksley, Sussex, UK). The intra-assay coefficients of variance were 2.7 and 0.5% for hemoglobin and hematocrit, respectively. Changes in plasma volume posttraining were calculated according to methods outlined previously (mean −1.7%) (19). The remaining whole blood was centrifuged at 4,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the plasma was removed, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis. Posttraining protein concentrations in plasma were adjusted to account for individual plasma volume changes.

Adipose tissue homogenization.

Adipose tissue samples (typically 200–300 mg) were homogenized in 500 μl, 5 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) buffer, containing 1 mM EDTA, 10% (wt/vol) sucrose, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) for 30 s using a handheld TissueRuptor (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). Homogenate was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and the internatant transferred to a fresh eppendorf and then stored at −80°C prior to protein analysis. Internatant protein concentration was determined using the DC Protein Assay Kit with a bovine serum albumin standard set used as protein standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

ELISAs and biochemical analysis.

IL-6 and IL-6R were determined in plasma and adipose tissue internatant pre- and posttraining via noncommercial sandwich ELISAs as described in detail previously (25, 37). Commercially available ELISA kits were used to determine plasma insulin (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) and adiponectin, high sensitivity (hs)-TNF-α, MCP-1, ICAM-1, and hs-IL-10 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) levels in plasma and adipose tissue. All inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variance were below 10%. Plasma glucose concentrations were determined by an enzymatic, colorimetric method using a bench top analyzer (Pentra 400, HORIBA ABX Diagnostics, Montpelier, France). Insulin sensitivity was assessed as the insulin sensitivity index (ISI) calculated using the OGTT values by the formula proposed by Matsuda and DeFronzo (40).

One-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1D-PAGE).

Protein homogenate from the adipose tissue samples was reduced by the addition of a quarter of a volume of 5× concentrated reducing solution [10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 500 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] and then heat-denatured by incubation for 10 min at 50°C. After cooling, one quarter of a volume of 5× Laemmli sample buffer was added [250 mM Tris·HCl (pH 6.8), 40% (vol/vol) glycerol, 5% (wt/vol) SDS, 0.005% (wt/vol) bromophenol] and proteins (35 μg/gel lane) resolved on 10% Bis-Tris gels for 2 h at 125 V using 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) running buffer within an X Cell surelock gel tank (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Proteins were either stained with colloidal blue stain (Invitrogen), or electroblotted at 80 V for 2 h onto a PVDF membrane for Western blotting. Each individual adipose tissue homogenate was gel-resolved two times for protein staining and subsequent Western blotting.

Matrix assisted laser-desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry.

Gels were stained with colloidal blue and prominent changes in the adipose tissue proteome after 2 wk HIIT were visually detected. Densitometric scanning of the gels using an Odyssey laser scanner (LIC-OR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was carried out to confirm the visually detected changes in the adipose tissue proteome before subjecting samples to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry protein identification. Colloidal Blue-stained proteins that were resolved by 1D-PAGE were excised from gels and transferred to a 96-well plate using an automated MassPrep robotic system (ProteomeWorks, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Gel pieces were destained, then reduced by incubation with dithiothreitol, and then alkylated with iodoacetamide, prior to digestion in situ with trypsin. Liberated tryptic peptides were desalted by binding and then elution from a C18 Zip-tip (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and then mixed with matrix (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid), before analysis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry using a Micromass MALDI (Waters, Milford, MA). A number of intact singularly charged peptides in the mass range of 800–3,000 Da were identified, and the masses applied to a search algorithm (MASCOT peptide mass fingerprint) to screen protein databases, such as SwissProt for peptide mass matches to enable protein identification (65).

Western (immuno)blotting.

Following protein identification by mass spectrometry, Western blot analysis was carried out to investigate any changes in the proteins in adipose tissue after 2 wk HIIT. Protein bound to the PVDF membrane was stained with Simply Blue Safestain (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature and then further fixed by drying overnight. Membranes were destained with 50% methanol, 10% acetic acid (vol/vol), to visualize protein bands and confirm even protein transfer across the membrane. Blots were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20, blocked with 5% milk fat in wash buffer for 1 h at room temperature, and then probed for 16 h at 4°C with primary antibodies. The primary antibodies used in this study were all rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) used at 1:500 dilution: anti-human annexin A2 (sc-9061), anti-human fatty acid synthase (sc-20140), and anti-human actin (sc-1616-R). Blots were washed, and then incubated with a secondary antibody (polyclonal goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-horseradish peroxidase conjugated, P0448, Dako, Ely, UK) at 1:1,000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed and then antibody localization visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Cramlington, UK), with light captured with a ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad). Relative levels of protein bands were quantified using QuantityOne software intrinsic to the ChemiDoc XRS+ system. Changes in annexin A2 and fatty acid synthase protein levels were normalized to actin levels.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical tests were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago, IL), and data are presented as means (SD). Data were checked for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Where parameters were not normally distributed the data were log transformed. Dependent t-tests were performed to assess differences between pre- and posttraining. Statistical significance was accepted at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

As a result of the 2 wk HIIT there was a significant reduction in waist circumference as well as a tendency for a decrease in hip circumference (P = 0.052), despite no significant changes in body mass or BMI. There was also a significant increase in V̇o2peak expressed in both absolute and relative terms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre- and posttraining values

| Pretraining | Posttraining | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass, kg | 91.0 (8.0) | 90.7 (7.8) | 0.518 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.1 (3.1) | 29.0 (3.2) | 0.501 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 96.3 (8.0) | 94.9 (8.4) | 0.029* |

| Hip circumference, cm | 109.8 (5.2) | 109 (6) | 0.052 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.88 (0.05) | 0.87 (0.05) | 0.269 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/l | 5.6 (0.6) | 5.0 (1.0) | 0.151 |

| Fasting insulin, mU/l | 7.8 (3.2) | 6.8 (3.5) | 0.268 |

| Insulin sensitivity index | 6.7 (4.6) | 7.7 (3.8) | 0.374 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 126 (8) | 126 (9) | 0.870 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 77 (12) | 79 (11) | 0.651 |

| V̇o2peak, l/min | 3.4 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.5) | 0.022* |

| V̇o2peak, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 38.4 (6.4) | 41.6 (5.2) | 0.037* |

Values are means (SD); n = 12. BMI, body mass index; V̇o2peak, peak oxygen consumption.

Significantly different compared with pretraining (P ≤ 0.05).

Inflammatory markers in the circulation and adipose tissue.

After training, plasma sIL-6R, adiponectin, and MCP-1 significantly decreased by approximately 9%, 10%, and 10% respectively, although there were no significant changes in IL-6, TNF-α, ICAM-1, or IL-10 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Concentration of IL-6, sIL-6R, ICAM-1, adiponectin, TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-10 in plasma at pre- and post-2 wk high-intensity intermittent training

| Pretraining | Posttraining | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6, pg/ml | 3.1 (3.0) | 2.6 (2.2) | 0.373 |

| sIL-6R, ng/ml | 42.0 (12.3) | 37.6 (9.6) | 0.050* |

| MCP-1, pg/ml | 145 (50) | 128 (38) | 0.047* |

| Adiponectin, μg/ml | 7.5 (3.5) | 6.7 (3.4) | 0.041* |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.918 |

| ICAM-1, pg/ml | 161 (25) | 154 (19) | 0.373 |

| IL-10, pg/ml | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.6) | 0.455 |

Values are means (SD); n = 12. sIL-6R, soluble IL-6 receptor; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactant protein 1.

Significantly different compared with pretraining (P ≤ 0.05).

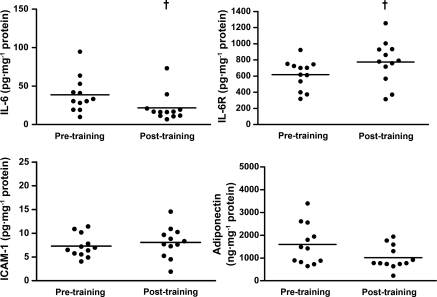

Within adipose tissue, IL-6 was significantly reduced by 33% (P = 0.036) and IL-6R significantly increased by 31% (P = 0.037). In addition there was a tendency for a decrease in adiponectin of 23% (P = 0.056) and no change in ICAM-1 after training (P = 0.480) (Fig. 1). TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-10 protein levels were below the limit of detection of the assay.

Fig. 1.

Concentration of IL-6, IL-6R, ICAM-1, and adiponectin in subcutaneous adipose tissue at pre- and post-2 wk high-intensity intermittent training (HIIT). Values are means (SD); n = 12. †Significantly different from pretraining (P ≤ 0.05).

Proteomic analyses.

An example of the protein profiles from five representative participants pre- and posttraining is included (Fig. 2A, top). There were clear reductions in the levels of proteins at ∼36 kDa and ∼270 kDa in posttraining homogenates for the majority of participants. Protein bands at these molecular weights were excised from gels from seven participants, and the protein bands analyzed by mass spectrometry. Although all participants displayed visible protein staining at the band positions of ∼36 and ∼270 kDa, the densities varied considerably between individuals. We therefore choose those whose protein showed high density at these two band positions (n = 7) to process for identification of the proteins. The ∼36 kDa protein was identified as annexin A2 and the ∼270 kDa protein as fatty acid synthase (FAS).

Fig. 2.

A, top: one-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis protein profiles in subcutaneous adipose tissue homogenate of 5 representative participants at pre- and post-2 wk HIIT. A, bottom: Western blotting protein bands for annexin A2, fatty acid synthase, and actin in 5 participants. Change in annexin A2 (B) and fatty acid synthase (C) in subcutaneous adipose tissue at pre- and post-2 wk HIIT. Values are means (SD); n = 12. *Significantly different from pretraining (P ≤ 0.05).

To further validate and additionally quantify these reductions in protein levels, Western blotting analysis was undertaken on the adipose tissue homogenates from all participants. An example of the Western blotting from five participants is included (Fig. 2A, bottom). Reductions in protein staining were supported by Western blotting, which for all participants collectively resulted in a significant 24% reduction (P = 0.046) in annexin A2 levels (Fig. 2B) and a significant 23% reduction (P = 0.016) in FAS levels (Fig. 2C), as a consequence of the exercise training. Annexin A2 levels were reduced in 9 of the 12 participants and FAS levels were reduced in 10 of the 12 participants; however, it should be noted that these changes did not correlate (P = 0.403).

DISCUSSION

Exercise regimens of varying intensities may improve well-being and combat some of the basal increase in inflammation associated with excessive fat deposition and other adverse health conditions including T2DM and CVD (1, 4, 61, 73). The results of this study indicate that in overweight and obese males, a 2 wk HIIT regimen can reduce inflammation in the circulation as well as subcutaneous adipose tissue and can induce a reduction in waist circumference and increase V̇o2peak, with 100% of HIIT sessions completed.

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine and exerts both pro- and anti-inflammatory actions (52). This is the first study to report a significant reduction in IL-6 in subcutaneous adipose tissue with exercise training. However, it is unclear whether this is due directly to the exercise or to a loss in fat, as reduced IL-6 in subcutaneous adipose tissue has been shown after weight loss in obese women through a hypocaloric diet but no exercise intervention (6). The same research group has also shown that IL-6 in subcutaneous adipose tissue is negatively correlated with insulin sensitivity (7). Previous studies have found no change in IL-6 mRNA expression in adipose tissue after 12 wk of aerobic training in obese females (44) or strength training in obese males (34), although these studies did not examine IL-6 protein changes in adipose tissue, and the exercise intensity was substantially lower. The finding of a decrease in IL-6 protein in adipose tissue in the present study could therefore be due to the higher exercise intensity elicited in this study. In the present study there was no significant change in circulating IL-6 posttraining, which could explain why insulin sensitivity was unaltered, as systemic IL-6 is strongly correlated with insulin resistance (6, 7, 22, 32). It is important to note that the present study focused on total changes in the protein concentration of inflammatory proteins within the adipose tissue as opposed to changes in protein secretion. Therefore, although there was a significant reduction of IL-6 in adipose tissue, the rate of IL-6 secretion from adipose tissue into the circulation may have been unaltered and could explain why there was no change in circulating IL-6. Other tissues and cells also contribute to circulating IL-6, with only ∼15–35% of circulating IL-6 at rest deriving from subcutaneous adipose tissue (41). The lack of correlation between the changes in adipose tissue and circulating levels is therefore understandable.

Within adipose tissue, only around 4–10% of IL-6 comes from adipocytes (21, 23); therefore it is likely that other immune cells such as macrophages are the main source of IL-6 production. Macrophage recruitment into adipose tissue is greater in obese compared with lean individuals (15, 68), although it seems that the size of the adipocytes triggers macrophage infiltration rather than overall obesity (18). MCP-1 is a chemoattractant known specifically to stimulate macrophage and monocyte recruitment into adipose tissue. MCP-1 levels are increased in obesity, resulting in an influx of macrophages and monocytes into the adipose tissue (13). In the present study, MCP-1 was not detectable in subcutaneous adipose tissue and furthermore has been shown to be higher in visceral adipose tissue (13); therefore it is likely that the decrease of this chemokine in the circulation is due to a reduced MCP-1 production in other tissues such as visceral adipose tissue.

IL-6R in subcutaneous adipose tissue was significantly increased posttraining, which is consistent with findings in skeletal muscle after 10 wk of knee extensor exercise training (2, 30). IL-6R has previously been shown to be expressed on the plasma membrane of ∼60% of adipocytes (7). The counter finding of a reduction in sIL-6R in plasma is also in support of previous studies showing similar changes in obese women after 6 mo of training (54, 72) and in chronic heart failure patients after a 12-wk exercise intervention (1). This finding is consistent with the current understanding that sIL-6R is independent of cell production and is derived from proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound IL-6R (37).

ICAM-1 is a vascular cell adhesion molecule that is used as a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction and can independently predict CVD (46). In the present study, no alterations were found in ICAM-1 in plasma or adipose tissue. Some research has shown improvements in circulating ICAM-1 with exercise training in individuals with metabolic disorders and T2DM (47, 48, 73); however, there were no changes in a group with normal glucose tolerance after a 4-wk exercise intervention (63). In all of these studies preintervention ICAM-1 concentrations were two to three times greater than in the present study. As with MCP-1, it has been demonstrated that ICAM-1 is greater in visceral fat in obese compared with lean individuals, but there is no difference in subcutaneous adipose tissue (11). Therefore, the reason for the absence of a reduction in circulating ICAM-1 in the present study could be that decreases in circulating ICAM-1 found in other studies are caused by a reduction in ICAM-1 production in visceral as opposed to subcutaneous fat, as well as lower pretraining circulating ICAM-1 in the present study than in the aforementioned studies.

The literature shows clear evidence that adiponectin levels are inversely correlated with BMI (3, 10, 14, 31, 51, 66, 69) and is increased after 1 yr of high-intensity exercise in T2DM patients (4). The present finding of a reduction in adiponectin in plasma and a tendency for this decrease to be replicated in adipose tissue (P = 0.056) is inconsistent with some existing literature. However, in a recent review (55), only three of eight randomized control trials involving exercise training resulted in an increase in plasma adiponectin, and there is some evidence, supported by the present study, that to increase adiponectin levels, at least in plasma, dietary restriction with a 10% weight loss is required (39). Christiansen and colleagues (17) support this concept presenting a small nonsignificant decrease in plasma adiponectin after a 3-mo exercise regimen, yet adiponectin was increased in a diet-only group and a combined diet plus exercise group. This research group demonstrated adiponectin mRNA in subcutaneous adipose tissue was increased in all groups, whereas other exercise-only interventions have found no changes in adiponectin mRNA in adipose tissue (34, 44), although none of these studies measured protein changes. An alternative explanation may relate to the fact that there are different isoforms of adiponectin expressing both anti- and proinflammatory actions (27, 42, 43). Haugen and Drevon (27) demonstrated that globular adiponectin induced TNF-α secretion, demonstrating pro-inflammatory properties, whereas in studies measuring total adiponectin, it is thought to exhibit overall anti-inflammatory properties, including enhancing insulin sensitivity (8, 71). Further work is required to determine whether functionality is related to changes in the various isoforms of adiponectin and to test the differences between dietary restriction and exercise interventions on the adiponectin response.

IL-10, MCP-1, and TNF-α were not detectable within subcutaneous adipose tissue, suggesting the dominant source of inflammation is visceral adipose tissue, which is consistent with other studies (11, 13, 23), although one ex vivo study found IL-6 to be greater in subcutaneous than visceral fat (24) and similarly adiponectin is more abundant in subcutaneous adipose tissue (21, 38). Despite the majority of evidence suggesting inflammatory proteins are present at greater concentrations in visceral than subcutaneous adipose tissue, visceral adipose tissue accounts for only 13% of total adipose tissue in obese men and 6% in obese women (49); therefore the contribution of subcutaneous adipose tissue to systemic low-grade inflammation could be substantial. Clarification of the protein concentration of inflammatory cytokines in adipose tissue is therefore required to substantiate the existing literature.

Additional proteomic analysis was carried out to determine if there were any gross changes in the wider subcutaneous adipose tissue proteome. Significant reductions of both annexin A2 and FAS were identified in adipose tissue after 2 wk HIIT. This is the first study to have shown a significant reduction of annexin A2 protein levels within subcutaneous adipose tissue as a consequence of exercise training. Annexin A2, primarily an intracellular protein, has previously been identified in human adipocytes (56). It is a multifunctional protein, whose activities include the ability to activate macrophages and stimulate cytokines and chemokines including IL-6, TNF-α, and ICAM-1 production in macrophages in vitro (59). Thus there is the possibility that annexin A2 may also correlate with other inflammatory markers, but further work is required to better determine a precise role of annexin A2 in inflammation.

Proteomic analysis also demonstrated a reduction of similar magnitude in the enzyme FAS in subcutaneous adipose tissue. Expression of FAS is elevated in both subcutaneous and visceral adipose depots in obese individuals, with increased subcutaneous mRNA FAS expression shown to be associated with high serum IL-6 and insulin resistance (9). The findings of the present study are in agreement with a report of reduced FAS in adipose tissue after 16 wk exercise training (62). The authors of this study also reported FAS was reduced to a greater extent after aerobic interval training compared with continuous moderate exercise. In contrast to these studies, an increase in mRNA expression of FAS has also been shown after 4 wk exercise training in subcutaneous fat (50), although this study did not look at translated FAS protein and therefore emphasizes the need to demonstrate any functional changes with protein analysis. The proteomic analysis was limited to an evaluation of the most visibly prominent protein level changes, but it is likely that other protein levels will be changed within the adipose tissue proteome as a consequence of this exercise regimen; however, a more extensive proteomic study was beyond the scope of this manuscript.

A decrease in waist circumference similar to the present study was found after 2 wk sprint interval training (70), although it seems unlikely that the decrease in waist circumference is simply due to the increased energy expenditure introduced due to the training protocol. Total energy expenditure in the present study was estimated to be ∼14,500 kJ for the six HIIT sessions, with an estimated additional ∼5,000 kJ due to excess postexercise oxygen consumption (35). This would theoretically cause a total body fat loss of ∼600 g of adipose tissue, which is unlikely to induce a mean reduction in waist circumference of ∼1.4 cm. Further studies are therefore required to determine the cause of the reduced waist circumference since abdominal adiposity was not measured in the present study.

Despite significant improvements in inflammatory proteins, waist circumference, and V̇o2peak, the present investigation found no improvement of insulin sensitivity after HIIT. A possible explanation for the discrepancy in findings between this study and others that did detail an increase of insulin sensitivity after 2 wk sprint interval training (45, 70) could be due to the timing of the posttraining OGTT. In the present study, the OGTT took place 46–48 h after training to eradicate any acute effects on insulin sensitivity from the last training session (28). A previous investigation in overweight and obese males has shown that insulin sensitivity although augmented 24 h after the last bout of exercise was lost at 72 h posttraining, suggesting the augmentation may be due to the effect of the last acute exercise bout (70). In contrast to these findings, utilizing the gold standard methodology of the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, before and after a 2 wk sprint training protocol, and sampling 72 h posttraining, found insulin sensitivity to be increased (45). In this study, however, the preexercise glucose infusion rate of the training group appeared low, and the posttraining sample, although significantly different from pretraining, was comparable to the sedentary control group and much lower than an acute exercise group, suggesting the pretraining value was unusually low. It is clear that the timing of the posttraining samples after the last exercise bout is critical when interpreting insulin sensitivity results.

In conclusion the present study provides novel evidence to support that HIIT, a high-intensity intermittent training protocol, is an appropriate form of exercise to induce both metabolic and inflammatory changes after only 2 wk. The protocol was suitable for an overweight and obese cohort, with all HIIT sessions completed by the participants. Although the training period is short and it is unlikely to have changed parameters independent of the training, future studies should consider introducing a control group when determining whether HIIT is suitable for different patient groups and if greater health benefits can be achieved over a longer training period.

GRANTS

We are also thankful to the Wellcome Trust for the funding of a summer scholarship to Miss Sarah Sribala-Sundaram.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.L. and M.A.N. conception and design of research; M.L., W.G.C., M.J.E., R.A.V., S.S.-S., and M.A.N. performed experiments; M.L., W.G.C., M.J.E., R.A.V., S.S.-S., and M.A.N. analyzed data; M.L., W.G.C., M.J.E., R.A.V., S.S.-S., and M.A.N. interpreted results of experiments; M.L. and W.G.C. prepared figures; M.L. and M.A.N. drafted manuscript; M.L., W.G.C., and M.A.N. edited and revised manuscript; M.L., W.G.C., and M.A.N. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the study participants. We would like to thank Dr. David Tooth of the University of Nottingham for mass spectrometry analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamopoulos S, Parissis J, Karatzas D, Kroupis C, Georgiadis M, Karavolias G, Paraskevaidis J, Koniavitou K, Coats AJ, Kremastinos DT. Physical training modulates proinflammatory cytokines and the soluble Fas/soluble Fas ligand system in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 653–663, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akerstrom TC, Krogh-Madsen R, Winther Petersen AM, Pedersen BK. Glucose ingestion during endurance training attenuates expression of myokine receptor. Exp Physiol 94: 1124–1131, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, Hotta K, Shimomura I, Nakamura T, Miyaoka K, Kuriyama H, Nishida M, Yamashita S, Okubo K, Matsubara K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257: 79–83, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, Fernando F, Cavallo S, Cardelli P, Fallucca S, Alessi E, Letizia C, Jimenez A, Fallucca F, Pugliese G. Anti-inflammatory effect of exercise training in subjects with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome is dependent on exercise modalities and independent of weight loss. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 20: 608–617, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartlett JD, Close GL, MacLaren DP, Gregson W, Drust B, Morton JP. High-intensity interval running is perceived to be more enjoyable than moderate-intensity continuous exercise: implications for exercise adherence. J Sports Sci 29: 547–553, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bastard JP, Jardel C, Bruckert E, Blondy P, Capeau J, Laville M, Vidal H, Hainque B. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 3338–3342, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bastard JP, Maachi M, Van Nhieu JT, Jardel C, Bruckert E, Grimaldi A, Robert JJ, Capeau J, Hainque B. Adipose tissue IL-6 content correlates with resistance to insulin activation of glucose uptake both in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 2084–2089, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med 7: 947–953, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berndt J, Kovacs P, Ruschke K, Kloting N, Fasshauer M, Schon MR, Korner A, Stumvoll M, Bluher M. Fatty acid synthase gene expression in human adipose tissue: association with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 50: 1472–1480, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blüher M, Bullen JW, Jr, Lee JH, Kralisch S, Fasshauer M, Klöting N, Niebauer J, Schon MR, Williams CJ, Mantzoros CS. Circulating adiponectin and expression of adiponectin receptors in human skeletal muscle: associations with metabolic parameters and insulin resistance and regulation by physical training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 2310–2316, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bošanská L, Michalský D, Lacinová Z, Dostálová I, Bártlová M, Haluzíková D, Matoulek M, Kasalický M, Haluzík M. The influence of obesity and different fat depots on adipose tissue gene expression and protein levels of cell adhesion molecules. Physiol Res 59: 79–88, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruun JM, Helge JW, Richelsen B, Stallknecht B. Diet and exercise reduce low-grade inflammation and macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue but not in skeletal muscle in severely obese subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E961–E967, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bruun JM, Lihn AS, Pedersen SB, Richelsen B. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 release is higher in visceral than subcutaneous human adipose tissue (AT): implication of macrophages resident in the AT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 2282–2289, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bruun JM, Lihn AS, Verdich C, Pedersen SB, Toubro S, Astrup A, Richelsen B. Regulation of adiponectin by adipose tissue-derived cytokines: in vivo and in vitro investigations in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E527–E533, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cancello R, Henegar C, Viguerie N, Taleb S, Poitou C, Rouault C, Coupaye M, Pelloux V, Hugol D, Bouillot JL, Bouloumié A, Barbatelli G, Cinti S, Svensson PA, Barsh GS, Zucker JD, Basdevant A, Langin D, Clément K. Reduction of macrophage infiltration and chemoattractant gene expression changes in white adipose tissue of morbidly obese subjects after surgery-induced weight loss. Diabetes 54: 2277–2286, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Christiansen T, Paulsen SK, Bruun JM, Pedersen SB, Richelsen B. Exercise-training versus diet-induced weight-loss on metabolic risk factors and inflammatory markers in obese subjects. A 12-week randomized intervention study. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E824–E831, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Christiansen T, Paulsen SK, Bruun JM, Ploug T, Pedersen SB, Richelsen B. Diet-induced weight loss and exercise alone and in combination enhance the expression of adiponectin receptors in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, but only diet-induced weight loss enhanced circulating adiponectin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 911–919, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, Wang S, Fortier M, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res 46: 2347–2355, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dill DB, Costill DL. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J Appl Physiol 37: 247–248, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 98–107, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fain JN, Madan AK, Hiler ML, Cheema P, Bahouth SW. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology 145: 2273–2282, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernandez-Real JM, Vayreda M, Richart C, Gutierrez C, Broch M, Vendrell J, Ricart W. Circulating interleukin 6 levels, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity in apparently healthy men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 1154–1159, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 847–850, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gletsu N, Lin E, Zhu JL, Khaitan L, Ramshaw BJ, Farmer PK, Ziegler TR, Papanicolaou DA, Smith CD. Increased plasma interleukin 6 concentrations and exaggerated adipose tissue interleukin 6 content in severely obese patients after operative trauma. Surgery 140: 50–57, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gray SR, Robinson M, Nimmo MA. Response of plasma IL-6 and its soluble receptors during submaximal exercise to fatigue in sedentary middle-aged men. Cell Stress Chaperones 13: 247–251, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guiraud T, Nigam A, Juneau M, Meyer P, Gayda M, Bosquet L. Acute responses to high-intensity intermittent exercise in CHD patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43: 211–217, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haugen F, Drevon CA. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB by high molecular weight and globular adiponectin. Endocrinology 148: 5478–5486, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hawley JA, Lessard SJ. Exercise training-induced improvements in insulin action. Acta Physiol 192: 127–135, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 95: 2409–2415, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keller C, Steensberg A, Hansen AK, Fischer CP, Plomgaard P, Pedersen BK. Effect of exercise, training, and glycogen availability on IL-6 receptor expression in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 99: 2075–2079, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kern PA, Di Gregorio GB, Lu T, Rassouli N, Ranganathan G. Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression. Diabetes 52: 1779–1785, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G. Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280: E745–E751, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kern PA, Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Bosch RJ, Deem R, Simsolo RB. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J Clin Invest 95: 2111–2119, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Klimcakova E, Polak J, Moro C, Hejnova J, Majercik M, Viguerie N, Berlan M, Langin D, Stich V. Dynamic strength training improves insulin sensitivity without altering plasma levels and gene expression of adipokines in subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 5107–5112, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Knab AM, Shanely RA, Corbin K, Jin F, Sha W, Nieman DC. A 45-minute vigorous exercise bout increases metabolic rate for 14 hours. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43: 1643–1648, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346: 393–403, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leggate M, Nowell MA, Jones SA, Nimmo MA. The response of interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-6 receptor isoforms following intermittent high intensity and continuous moderate intensity cycling. Cell Stress Chaperones 15: 827–833, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lihn AS, Bruun JM, He G, Pedersen SB, Jensen PF, Richelsen B. Lower expression of adiponectin mRNA in visceral adipose tissue in lean and obese subjects. Mol Cell Endocrinol 219: 9–15, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Madsen EL, Rissanen A, Bruun JM, Skogstrand K, Tonstad S, Hougaard DM, Richelsen B. Weight loss larger than 10% is needed for general improvement of levels of circulating adiponectin and markers of inflammation in obese subjects: a 3-year weight loss study. Eur J Endocrinol 158: 179–187, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22: 1462–1470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A, Katz DR, Miles JM, Yudkin JS, Klein S, Coppack SW. Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 4196–4200, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, Hotta K, Nishida M, Takahashi M, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation 100: 2473–2476, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Okamoto Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Hotta K, Nishida M, Takahashi M, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived plasma protein, inhibits endothelial NF-kappaB signaling through a cAMP-dependent pathway. Circulation 102: 1296–1301, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Polak J, Klimcakova E, Moro C, Viguerie N, Berlan M, Hejnova J, Richterova B, Kraus I, Langin D, Stich V. Effect of aerobic training on plasma levels and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue gene expression of adiponectin, leptin, interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha in obese women. Metabolism 55: 1375–1381, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Richards JC, Johnson TK, Kuzma JN, Lonac MC, Schweder MM, Voyles WF, Bell C. Short-term sprint interval training increases insulin sensitivity in healthy adults but does not affect the thermogenic response to beta-adrenergic stimulation. J Physiol 588: 2961–2972, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Roitman-Johnson B, Stampfer MJ, Allen J. Plasma concentration of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and risks of future myocardial infarction in apparently healthy men. Lancet 351: 88–92, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roberts CK, Won D, Pruthi S, Kurtovic S, Sindhu RK, Vaziri ND, Barnard RJ. Effect of a short-term diet and exercise intervention on oxidative stress, inflammation, MMP-9, and monocyte chemotactic activity in men with metabolic syndrome factors. J Appl Physiol 100: 1657–1665, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roberts CK, Won D, Pruthi S, Lin SS, Barnard RJ. Effect of a diet and exercise intervention on oxidative stress, inflammation and monocyte adhesion in diabetic men. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 73: 249–259, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ross R, Shaw KD, Rissanen J, Martel Y, de Guise J, Avruch L. Sex differences in lean and adipose tissue distribution by magnetic resonance imaging: anthropometric relationships. Am J Clin Nutr 59: 1277–1285, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ruschke K, Fishbein L, Dietrich A, Klöting N, Tönjes A, Oberbach A, Fasshauer M, Jenkner J, Schön MR, Stumvoll M, Blüher M, Mantzoros CS. Gene expression of PPARgamma and PGC-1alpha in human omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues is related to insulin resistance markers and mediates beneficial effects of physical training. Eur J Endocrinol 162: 515–523, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ryan AS, Nicklas BJ. Reductions in plasma cytokine levels with weight loss improve insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese postmenopausal women. Diabetes Care 27: 1699–1705, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813: 878–888, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 116: 1793–1801, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Silverman NE, Nicklas BJ, Ryan AS. Addition of aerobic exercise to a weight loss program increases BMD, with an associated reduction in inflammation in overweight postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 84: 257–265, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Simpson KA, Singh MA. Effects of exercise on adiponectin: a systematic review. Obesity 16: 241–256, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Singh NR, Rondeau P, Hoareau L, Bourdon E. Identification of preferential protein targets for carbonylation in human mature adipocytes treated with native or glycated albumin. Free Radic Res 41: 1078–1088, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sowers JR. Obesity as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Med 115: 37S–41S, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Swain D, Franklin BA. Comparison of cardioprotective benefits of vigorous versus moderate intensity aerobic exercise. Am J Cardiol 97: 141–147, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Swisher JF, Khatri U, Feldman GM. Annexin A2 is a soluble mediator of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol 82: 1174–1184, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Talanian JL, Galloway SD, Heigenhauser GJ, Bonen A, Spriet LL. Two weeks of high-intensity aerobic interval training increases the capacity for fat oxidation during exercise in women. J Appl Physiol 102: 1439–47, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thompson D, Markovitch D, Betts JA, Mazzatti DJ, Turner J, Tyrrell RM. Time course of changes in inflammatory markers during a 6-mo exercise intervention in sedentary middle-aged men: a randomized-controlled trial. J Appl Physiol 102: 1439–1447, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tjønna AE, Lee SJ, Rognmo O, Stølen TO, Bye A, Haram PM, Loennechen JP, Al-Share QY, Skogvoll E, Slørdahl SA, Kemi OJ, Najjar SM, Wisløff U. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome: a pilot study. Circulation 118: 346–354, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tönjes A, Scholz M, Fasshauer M, Kratzsch J, Rassoul F, Stumvoll M, Blüher M. Beneficial effects of a 4-week exercise program on plasma concentrations of adhesion molecules. Diabetes Care 30: e1, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br J Nutr 92: 347–355, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vigneswara V, Lowenson JD, Powell CD, Thakur M, Bailey K, Clarke S, Ray DE, Carter WG. Proteomic identification of novel substrates of a protein isoaspartyl methyltransferase repair enzyme. J Biol Chem 281: 32619–32629, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vilarrasa N, Vendrell J, Maravall J, Broch M, Estepa A, Megia A, Soler J, Simon I, Richart C, Gomez JM. Distribution and determinants of adiponectin, resistin and ghrelin in a randomly selected healthy population. Clin Endocrinol 63: 329–335, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Can Med Assoc J 174: 801–809, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112: 1796–1808, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, Tataranni PA. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 1930–1935, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Whyte LJ, Gill JM, Cathcart AJ. Effect of 2 weeks of sprint interval training on health-related outcomes in sedentary overweight/obese men. Metabolism 59: 1421–1428, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, Mori Y, Ide T, Murakami K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Ezaki O, Akanuma Y, Gavrilova O, Vinson C, Reitman ML, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Yoda M, Nakano Y, Tobe K, Nagai R, Kimura S, Tomita M, Froguel P, Kadowaki T. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med 7: 941–946, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. You T, Berman DM, Ryan AS, Nicklas BJ. Effects of hypocaloric diet and exercise training on inflammation and adipocyte lipolysis in obese postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 1739–1746, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zoppini G, Targher G, Zamboni C, Venturi C, Cacciatori V, Moghetti P, Muggeo M. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise training on plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovas 16: 543–549, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]