Abstract

Peripheral artery tonometry (PAT) is a novel method for assessing arterial stiffness of small digital arteries. Pulse pressure can be regarded as a surrogate of large artery stiffness. When ankle-brachial index (ABI) is calculated using the higher of the two ankle systolic pressures as denominator (ABI-higher), leg perfusion can be reliably estimated. However, using the lower of the ankle pressures to calculate ABI (ABI-lower) identifies more patients with isolated peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in ankle arteries. We aimed to compare the ability of PAT, pulse pressure, and different calculations of ABI to detect atherosclerotic disease in lower extremities. We examined PAT, pulse pressure, and ABI in 66 cardiovascular risk subjects in whom borderline PAD (ABI 0.91 to 1.00) was diagnosed 4 years earlier. Using ABI-lower to diagnose PAD yielded 2-fold higher prevalence of PAD than using ABI-higher. Endothelial dysfunction was diagnosed in 15/66 subjects (23%). In a bivariate correlation analysis, pulse pressure was negatively correlated with ABI-higher (r = −0.347, p = 0.004) and with ABI-lower (r = −0.424, p < 0.001). PAT hyperemic response was not significantly correlated with either ABI-higher (r = −0.148, p = 0.24) or with ABI-lower (r = −0.208, p = 0.095). Measurement of ABI using the lower of the two ankle pressures is an efficient method to identify patients with clinical or subclinical atherosclerosis and worth performing on subjects with pulse pressure above 65 mm Hg. The usefulness of PAT measurement in detecting PAD is vague.

Keywords: Ankle-brachial index, peripheral arterial disease, hypertension

Pulse pressure—the difference between the systolic and diastolic blood pressure—can be used as an indirect measurement of large artery stiffness and thus atherosclerotic disease.1 A novel method for assessing arterial stiffness and dynamics of small arteries is peripheral artery tonometry (PAT).2 With this technique, it is possible to measure arterial pulse wave amplitude in the finger in response to induced reactive hyperemia. The PAT hyperemic response is suggested to depend on nitric oxide release,3 and might hold promise to early identification of subjects at increased risk of developing occlusive arterial disease.

Measurement of ankle-brachial index (ABI) has long been used to assess perfusion in lower extremities. For this purpose, ABI has been calculated by dividing the higher of the two ankle pressures, that is, systolic blood pressures of the posterior tibial (PT) artery and dorsalis pedis (DP) artery, by the higher of the left and right brachial artery pressures.4 However, this method has been recently shown to underestimate the true prevalence of PAD. More patients with isolated atherosclerosis of PT or DP could be identified using the lower of the two ankle pressures in calculating ABI.5 In this way, a higher number of patients with increased risk for future cardiovascular events can be identified.6

We had the opportunity to measure pulse pressure, ABI, and peripheral vascular function with PAT in a cohort of cardiovascular risk subjects. We aimed at investigating whether PAT hyperemic response (measured on the upper extremities) correlates with pulse pressure (measured on the upper extremities) and ABI (measured on the lower extremities), both of which are well-known surrogates of cardiovascular disease.

METHODS

Patients

The study sample of cardiovascular risk subjects was drawn from the Harmonica Project, a population survey designed to evaluate cardiovascular risk factors in people in the age group of 45 to 70 years in southwestern Finland. A detailed description of the enrollment and examination methods has been published earlier.7 In 2005 and 2006, ABI was measured in 972 nonclaudicant subjects with hypertension, metabolic syndrome, newly detected glucose disorders, body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, or a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease death of 5% or more according to the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) system.8 None of the subjects had established cardiovascular or renal disease or previously diagnosed with diabetes. Of the 972 examined subjects, 164 (17%) had borderline PAD defined as ABI 0.91 to 1.00 using the lower of the two ankle pressures to calculate ABI. In this study, 66 patients were examined in the 2009.

Informed Consent

All participants provided written informed consent for the project and subsequent medical research. The study protocol and consent forms were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Satakunta Hospital District.

Measurement of Blood Pressure

A trained nurse measured the blood pressure with a mercury sphygmomanometer with subjects in a sitting posture, after resting for ≥5 minutes. In each subject, the mean of left and right brachial blood pressure was used in the study. Pulse pressure was calculated by subtracting the mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) from the mean systolic blood pressure (SBP).

Measurement of ABI

A trained nurse measured ABI using a blood pressure cuff and Doppler instrument (UltraTec® PD1v with a vascular probe of 5 MHz, Medema T/A Omega Medical Supplies Ltd., London, UK). SBP of the left and right brachial arteries and SBP of the left and right PT and DP were measured if available. The cuff was placed just above the level of the malleoli. ABI was the higher/lower ankle SBP divided by the higher brachial SBP. Subjects who had ABI value ≤0.90 in either leg were categorized as having PAD. Subjects with ABI 0.91 to 1.00 were considered as having borderline PAD. ABI 1.01 to 1.40 was considered normal.

Measurement of Small Artery Dynamics

Endothelial function of small arteries was assessed using an Endo-PAT device (Itamar Medical Ltd., Caesarea, Israel). During the measurement the subjects sat in a chair with their hands at the level of their heart, fingers hanging freely. Fingertip probes were placed on both index fingers and pulse wave amplitudes were recorded during the study. After a 5-minute baseline measurement, arterial flow was occluded using a cuff on the nondominant arm. The cuff was inflated to 40 mm Hg above SBP. After 5 minutes of occlusion, the cuff was rapidly deflated to allow reactive hyperemia to occur. Pulse wave amplitudes were recorded again for at least 5 minutes. The software provided by the manufacturer was then used to compare the arterial pressure ratio in the two fingers before and after occlusion. It then calculated a reactive hyperemia index (RHI), which was a ratio of the average pulse wave amplitude measured over 60 seconds, starting 1 minute after cuff deflation, to the average pulse wave amplitude measured at the baseline. The other arm served as a control and the ratio was corrected for changes in the systemic vascular tone. An RHI value of <1.67 was used as a cut-off value to diagnose endothelial dysfunction.9

Statistical Analysis

Data were recorded to SPSS for Windows 18.0 database (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Using the database, descriptive analysis was done. The data were presented as means with standard deviations or as counts with percentages. Chi-square test was used for statistical comparisons between groups in measures with binary distribution. The independent samples t-test was used for continuous variables. Spearman correlation tests were used to analyze bivariate associations between pulse pressure and ABI categories.

RESULTS

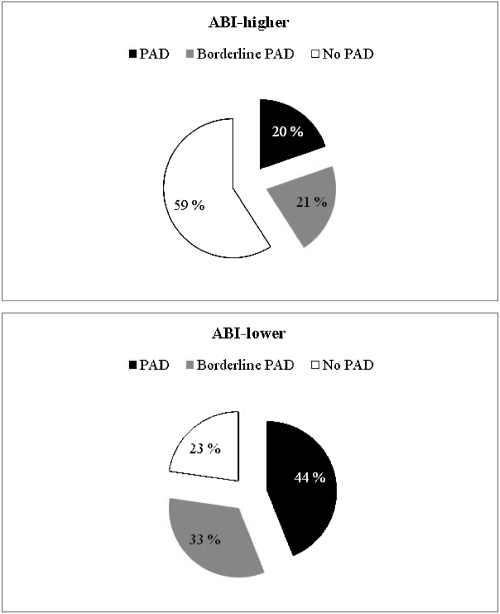

We measured ABI, pulse pressure, and RHI in 66 cardiovascular risk subjects in whom borderline PAD had been diagnosed using the lower of the two ankle pressures to calculate ABI. When the subjects were reexamined 4 years later, ABI was calculated using the higher (ABI-higher) and the lower (ABI-lower) ankle pressure. The prevalence of PAD and borderline PAD varied significantly (p < 0.001) according to different calculations of ABI (Fig. 1). Characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences between genders in demographic or clinical characteristics.

Figure 1.

Definition of patient groups with regard to different calculations of ankle-brachial index. ABI, ankle-brachial index; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Subjects (n = 66)

| Female (n = 39) | Male (n = 27) | All (n = 66) | p Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (years, mean) (SD) | 62.4 (6.5) | 63.4 (6.4) | 62.8 (6.5) | 0.52 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 0.010 | |||

| Current | 9 (23) | 5 (19) | 14 (21) | |

| Former | 8 (21) | 15 (56) | 23 (35) | |

| Clinical | ||||

| ABI-higher, mean (SD) | 1.00 (0.11) | 1.03 (0.15) | 1.01 (0.13) | 0.52 |

| ABI-lower, mean (SD) | 0.90 (0.10) | 0.93 (0.15) | 0.91 (0.13) | 0.33 |

| SBP (mm Hg, mean) (SD) | 154 (21) | 148 (20) | 151 (21) | 0.25 |

| DBP (mm Hg, mean) (SD) | 86 (11) | 86 (8) | 86 (10) | 0.10 |

| PP (mm Hg, mean) (SD) | 67 (16) | 61 (17) | 65 (2) | 0.15 |

| RHI, mean (SD) | 2.20 (0.57) | 1.97 (0.51) | 2.11 (0.55) | 0.11 |

p value between females and males.

Low RHI indicating endothelial dysfunction was measured in 15/66 subjects (23%), out of whom 1/15 (7%) had PAD and 3/15 (20%) had borderline PAD when ABI-higher was used for diagnosis. Corresponding figures with ABI-lower were 3/15 (20%) and 6/15 (40%), respectively. Symptoms of intermittent claudication developed in 9/66 (14%) of the study subjects, but only 1 of these patients had low RHI (p = 0.37).

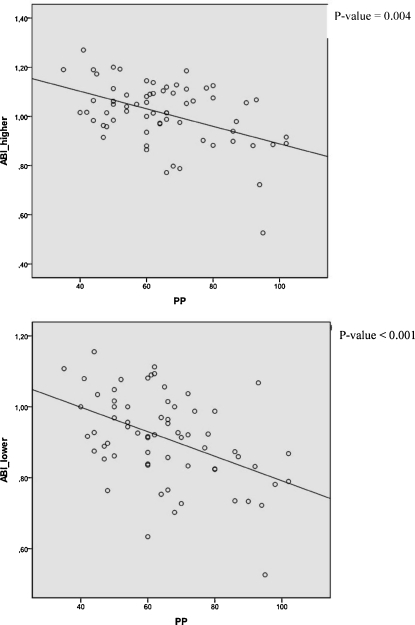

In a bivariate correlation analysis, pulse pressure was negatively correlated with ABI-higher (r = −0.347, p = 0.004) and with ABI-lower (r = −0.424, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Pulse pressure correlated positively with RHI (r = 0.291, p = 0.018), but RHI was not significantly correlated with either ABI-higher (r = −0.148, p = 0.24) or with ABI-lower (r = −0.208, p = 0.095).

Figure 2.

Correlations between ABI-higher and ABI-lower, and pulse pressure. ABI, ankle-brachial index; PP, pulse pressure.

Pulse pressure ≥65 mm Hg was measured in 30/66 subjects (45.5%). Table 2 shows the sensitivity, specificity, and the positive predictive value of pulse pressure ≥65 mm Hg to diagnose PAD according to different methods used for ABI calculation.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Properties of PP to Detect Peripheral Arterial Disease Defined by ABI Using Higher (ABI-Higher) or Lower (ABI-Lower) of the Two Ankle Pressures

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive Predictive Value (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABI-higher | |||

| PP ≥65 mm Hg | 77 | 62 | 33 |

| ABI-lower | |||

| PP ≥65 mm Hg | 59 | 62 | 57 |

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of 66 cardiovascular risk subjects with borderline PAD using ABI-lower as definition, worsening of ABI to PAD occurred in 44%, in 33% ABI remained in the previous level, and in 23% ABI value improved over 4 years of follow-up. The prevalence of PAD was 2-fold lower when ABI-higher was used. Thus, selection of the method of calculating ABI is important and should be used with regard to the objective of the study. ABI-higher should be used when assessing leg perfusion, and ABI-lower when searching for subjects at elevated cardiovascular risk.6

A person having ABI ≤0.90 using the higher of the two ankle pressures has presumably occlusive arterial disease in a proximal artery of the leg or in both ankle arteries, whereas a person with ABI ≤0.90 using the lower of the ankle pressures may have isolated atherosclerosis of PT or DP. Thus, the sensitivity of elevated pulse pressure—a surrogate marker of large artery stiffness—is high in regard with ABI-higher. However, the positive predictive value of elevated pulse pressure is higher when ABI-lower instead of ABI-higher is used for diagnosis of PAD. This is because the predictive value of a test is affected by the prevalence of the disease (Table 2). There is increasing evidence that pulse pressure predicts the development of coronary heart disease,10,11 heart failure,12,13 and stroke14,15 better than the other parameters of blood pressure. In our study, pulse pressure correlated only modestly with PAT hyperemic response. Elevated pulse pressure might produce higher hyperemic pulse amplitude in digit and thus interfere in recording with PAT device.

Our results show that PAT hyperemic response was not significantly correlated with either ABI-higher or with ABI-lower. The flow of small resistance arteries is regulated by vascular structure and tone, which is controlled by a variety of mechanical and biochemical stimuli. Ferré et al demonstrated recently that high-density lipoprotein cholesterol had a strong, positive correlation with small artery reactive hyperemia as measured by PAT device.16 In the Framingham heart study, PAT hyperemic response was inversely related to multiple cardiovascular risk factors, in particular obesity-associated metabolic risk factors.17 We have previously demonstrated that there is no association between either impaired glucose homeostasis or metabolic syndrome and PAD in a cohort of cardiovascular risk subjects without previously known cardiovascular disease or diabetes.18 Taken together, these results suggest that ABI and RHI measure different aspects of vascular structure and dynamics. As ABI measurement is focused on large- or medium-sized arteries and PAT testing on small digital arteries, toe pressure or metatarsal pulse volume recording would have perhaps been a better target for comparison. Although we cannot determine any causal relationships from our cross-sectional study with limited number of participants, we find it possible that PAT testing may provide an additional level of risk stratification beyond ABI measurement. The prognostic usefulness of ABI measurement in clinical practice is well defined19 but the exact role of PAT testing in this regard is not clear.

In conclusion, measurement of ABI using the lower of the two ankle pressures is an efficient method to identify patients with clinical or subclinical atherosclerosis and worth performing on subjects with pulse pressure above 65 mm Hg. The usefulness of PAT measurement in detecting PAD is vague. Differences in arterial physiology across various vascular beds might explain these findings, and further studies are needed to evaluate these methods in the cardiovascular risk prediction.

References

- Glasser S P, Arnett D K, McVeigh G E, et al. Vascular compliance and cardiovascular disease: a risk factor or a marker? Am J Hypertens. 1997;10(10 Pt 1):1175–1189. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg N M, Benjamin E J. Assessment of endothelial function using digital pulse amplitude tonometry. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2009;19(1):6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohria A, Gerhard-Herman M, Creager M A, Hurley S, Mitra D, Ganz P. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of digital pulse volume amplitude in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(2):545–548. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01285.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren L, Hiatt W R, Dormandy J A, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33(Suppl 1):S1–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder F, Diehm N, Kareem S, et al. A modified calculation of ankle-brachial pressure index is far more sensitive in the detection of peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(3):531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinola-Klein C, Rupprecht H J, Bickel C, et al. AtheroGene Investigators Different calculations of ankle-brachial index and their impact on cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation. 2008;118(9):961–967. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.763227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen P, Aarnio P, Saaresranta T, Jaatinen P, Kantola I. Glucose homeostasis in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):945–949. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.104869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy R M, Pyörälä K, Fitzgerald A P, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(11):987–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti P O, Pumper G M, Higano S T, Holmes D R, Jr, Kuvin J T, Lerman A. Noninvasive identification of patients with early coronary atherosclerosis by assessment of digital reactive hyperemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(11):2137–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin S S, Khan S A, Wong N D, Larson M G, Levy D. Is pulse pressure useful in predicting risk for coronary heart Disease? The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1999;100(4):354–360. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn R J, Chae C U, Guralnik J M, Taylor J O, Hennekens C H. Pulse pressure and mortality in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2765–2772. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae C U, Pfeffer M A, Glynn R J, Mitchell G F, Taylor J O, Hennekens C H. Increased pulse pressure and risk of heart failure in the elderly. JAMA. 1999;281(7):634–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Berger A K, Abramson J, et al. Pulse pressure and risk of cardiovascular events in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(9):980–986. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01974-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen W B, Lindenstrøm E, Vestbo J, Jensen G B. Is diastolic hypertension an independent risk factor for stroke in the presence of normal systolic blood pressure in the middle-aged and elderly? Am J Hypertens. 1997;10(6):634–639. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(96)00505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanski M J, Davis B R, Pfeffer M A, Kastantin M, Mitchell G F. Isolated systolic hypertension: prognostic information provided by pulse pressure. Hypertension. 1999;34(3):375–380. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré R, Aragonès G, Plana N, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and apolipoprotein A1 levels strongly influence the reactivity of small peripheral arteries. Atherosclerosis. 2011;216(1):115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg N M, Keyes M J, Larson M G, et al. Cross-sectional relations of digital vascular function to cardiovascular risk factors in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2008;117(19):2467–2474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen P E, Syvänen K T, Vesalainen R K, et al. Ankle-brachial index is lower in hypertensive than in normotensive individuals in a cardiovascular risk population. J Hypertens. 2009;27(10):2036–2043. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832f4f54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowkes F GR, Murray G D, Butcher I, et al. Ankle brachial index collaboration. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(2):197–208. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]