Abstract

Using current chemotherapy protocols, over 55% of lymphoma patients fail treatment. Novel agents are needed to improve lymphoma survival. The manganese porphyrin, MnTE-2-PyP5+, augments glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in WEHI7.2 murine thymic lymphoma cells, suggesting that it may have potential as a lymphoma therapeutic. However, the mechanism by which MnTE-2-PyP5+ potentiates glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is unknown. Previously, we showed that glucocorticoid treatment increases the steady state levels of hydrogen peroxide ([H2O2]ss) and oxidizes the redox environment in WEHI7.2 cells. In the current study, we found that when MnTE-2-PyP5+ is combined with glucocorticoids, it augments dexamethasone-induced oxidative stress however, it does not augment the [H2O2]ss levels. The combined treatment depletes GSH, oxidizes the 2GSH:GSSG ratio, and causes protein glutathionylation to a greater extent than glucocorticoid treatment alone. Removal of the glucocorticoid-generated H2O2 or depletion of glutathione by BSO prevents MnTE-2-PyP5+ from augmenting glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. In combination with glucocorticoids, MnTE-2-PyP5+ glutathionylates p65 NF-κB and inhibits NF-κB activity. Inhibition of NF-κB with SN50, an NF-κB inhibitor, enhances glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis to the same extent as MnTE-2-PyP5+. Taken together, these findings indicate that: 1) H2O2 is important for MnTE-2-PyP5+ activity; 2) Mn-TE-2-PyP5+ cycles with GSH; and 3) MnTE-2-PyP5+ potentiates glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by glutathionylating and inhibiting critical survival proteins, including NF-κB. In the clinic, over-expression of NF-κB is associated with a poor prognosis in lymphoma. MnTE-2-PyP5+ may therefore, synergize with glucocorticoids to inhibit NF-κB and improve current treatment.

Keywords: MnTE-2-PyP5+, dexamethasone, lymphoma, hydrogen peroxide, glutathione, glutathionylation, NF-κB

Introduction

The standard treatment for the majority of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) consists of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone, a combination chemotherapy known as CHOP [1]. Recently, rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody was added to the standard treatment of several NHL subtypes [2]. Unfortunately, the response to therapy has been heterogeneous. Forty percent of patients treated with CHOP initially respond; however, less than 30% of patients receiving treatment achieve long term survival [1]. Novel agents are needed that will work synergistically with the existing therapy to improve the overall survival of lymphoma patients.

Glucocorticoids, a class of steroid hormones that includes prednisone, are a central component of the CHOP regimen. The efficacy of glucocorticoids stems from their ability to induce apoptosis in lymphoid cells. We recently reported that a manganese porphyrin, Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin (MnTE-2-PyP5+), works in combination with glucocorticoids to augment apoptosis in WEHI7.2 murine thymic lymphoma cell cultures and primary follicular lymphoma cells [3]. MnTE-2-PyP5+ also sensitizes WEHI7.2 cells to cyclophosphamide, and does not affect the cells’ response to vincristine or doxorubicin. In H9c2 cardiomyocytes, MnTE-2-PyP5+ attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, a major adverse side effect in the treatment of lymphoma [3]. The efficacy of MnTE-2-PyP5+ in lymphoma cells suggests that it can be used in synergy with CHOP to improve lymphoma treatment and ultimately patient survival. However, the mechanism by which MnTE-2-PyP5+ potentiates glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphocytes is unknown.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ has been shown to act as a superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic in cell-free assays [4,5], and in a superoxide-specific assay in SOD deficient E.coli [6]. In WEHI7.2 and multiple myeloma cells, increasing the expression of MnSOD enhances glucocorticoid sensitivity [3,7]. Due to its highly positive metal-centered reduction potential (+ 228 mV vs NHE), MnTE-2-PyP5+ may redox cycle with flavin-containing enzymes such as NADPH oxidase and cytochrome P450 reductase, and small molecule reductants such as ascorbate, glutathione, and tetrahydrobiopterin [8-12]. Thus, MnTE-2-PyP5+ may act both as an anti- and pro-oxidant; in the latter case it can increase the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Given that MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis, the goals of this study are to: 1) determine the molecular mechanism that allows MnTE-2-PyP5+ to synergize with glucocorticoid treatment; and 2) identify critical targets of MnTE-2-PyP5+.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Murine thymic lymphoma WEHI7.2 cells were maintained in suspension in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium-low glucose (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified environment. WEHI7.2 cell variants overexpressing rat catalase (CAT38-1.4 fold increase; CAT2-2 fold increase) [13] were also maintained in suspension and supplemented with 800 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). One week prior to each experiment, variant cells were cultured in medium without G418.

Molt-4 and Jurkat cells were obtained from Dr. Lisa Rimsza and Dr. Terry Landowski (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ), respectively. Cells were maintained in suspension in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC, Manassas, VA); 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen) and 50U/ml each of penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cell cultures were incubated in a controlled humidified 5% CO2 environment.

Reagents and Drug Treatments

MnTE-2-PyP5+ was provided by Dr. James D. Crapo. All other drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. The sensitivity of WEHI7.2 cells to dexamethasone was determined by treating cells with a final concentration of 1 μM dexamethasone in an ethanol vehicle (0.01% final concentration) for 12 hours. Molt4 and Jurkat cells were treated with 500 μM and 250 μM dexamethasone for 48 hours, respectively. To test the effect of MnTE-2-PyP5+ on the dexamethasone response, WEHI7.2 cells were pretreated with 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+, and Molt4 and Jurkat cells were pretreated with 0.5 μM MnTE-2-PyP5+, 2 hours prior to the addition of dexamethasone. The concentrations were selected based on a dose-response curve. The concentrations chosen are the EC values for MnTE-2-PyP5+ 50 in the different cell lines. SN50 (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ), an NF-κB inhibitor, was used at a concentration of 10 μM.

Cell Viability Measurements

To determine the effect of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone or MnTE-2-PyP5+ and H2O2 on the number of viable cells, the relative cell number was measured after 12 hours of treatment, using the Non-radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). Absorbances were read at 490 nm using a Synergy HT plate reader (Bio Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Apoptosis Measurements

The ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone to induce apoptosis was measured by calculating caspase 3 activity and by quantitating the percentage of cells that stained positive for annexin V using flow cytometry. Caspase 3 activity was measured using an assay dependent on the enzymatic cleavage of a synthetic caspase 3 specific substrate, Ac-DEVD-p-nitroanilide (pNA) (BIOMOL International LTD, Bangkok, Thailand), as described previously [3]. Caspase 3 activity was normalized to cellular protein. For all experiments described in this study, the cellular protein was measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The fraction of apoptotic cells was also determined by staining cells with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled annexin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and propidium iodide (Molecular Probes) or 7-AAD (R & D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Cellular fluorescence was measured and analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer with Cell Quest Software (Beckton Dickenson, San Jose, CA) or an EPICS XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter, Corp., Miami, FL). Cells that were positive for annexin V staining and negative for propidium iodide or 7-AAD were considered apoptotic. Ten thousand cells were analyzed per sample. Numbers less than 5% different were considered within the error of the machine after calibration for this assay.

Drug Synergy Analysis

The following mathematical drug synergy model was used to determine whether the interaction between the porphyrin and dexamethasone is additive or synergistic:

where Fa is the fractional response to drug A alone, Fb is the fractional response of drug B alone, and ER is the expected response when the two drugs interact in an additive manner [14]. If the observed response is greater than the expected response, the interaction between the two drugs is synergistic. If the observed response is lower than the expected response, the interaction between the two drugs is antagonistic.

DCF Measurements

The overall intracellular levels of ROS were measured using the fluorescent probes 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′7′dichlorofluorescin diacetate (cDCFH-DA) and 2′7′dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Invitrogen). Both dyes are transported across the cell membrane and are deacetylated by esterases. cDCFH will fluoresce once the acetate groups are removed, but DCFH forms the non-fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorfluorescein (DCFH). This compound is trapped inside the cell and will fluoresce only in the presence of ROS [15]. Cells were washed with DMEM containing 0.5% calf serum, then incubated 2 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified environment in 0.5% DMEM supplemented with 20 μM cDCFH-DA or DCFH-DA. Thirty minutes before analysis, 5 μg/ml propidium iodide was added to the medium. Fluorescence was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer with Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Ten thousand cells were analyzed per sample. Cells that stained positive for propidium iodide were excluded from the analysis. The DCF fluorescence was corrected for the relative cDCFH fluorescence to account for differences in dye uptake between dexamethasone and control-treated cells.

Imaging Redox Environment Changes: roGFP2 Measurements

The redox sensitive GFP plasmid, p-EGFP-N1/roGFP2 was a generous gift from Dr. S. James Remington (University of Oregon, Eugene, OR) [16]. The plasmid was electroporated into WEHI7.2 cells using the Amaxa Nucleofactor™ II kit (Amaxa GmbH, Germany). Following electroporation, cells were grown in phenol-red free DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% calf serum for 24 hours, to allow the cells to recover. Cells were then pretreated with 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ followed by 1 μM dexamethasone (or the appropriate controls) for 8 hours. An 8 hour treatment time was chosen because it is still within the signaling phase of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis and because previous studies suggest that 12 hours of dexamethasone treatment oxidizes the roGFP2 to nearly 90% [17]. Thus, to be able to measure the effect of MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone, an earlier time point within the signaling phase was used. Cells were imaged using the DeltaVision Restoration Microscopy System (Applied Precision, Inc., Issaquah, WA) using excitation wavelengths at 407 nm and 488 nm and a 510/521 nm emission filter. Data were collected and processed using Scion Image (Scion, Frederick, MD). Images were corrected for background fluorescence by subtracting the intensity of a nearby cell-free region. Fluorescence excitation ratios were then calculated by dividing the integrated intensities of the cells at different excitation wavelengths using the mathematical formulas described in Hanson et al. [16]. Between 15 and 20 cells were analyzed per cell per treatment.

Amplex Red™ Measurements

H2O2 efflux was measured using the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked fluorometric indicator Amplex Red™ (Invitrogen) [18]. Briefly, cells were resuspended in phenol red-free DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories) containing 50 μM Amplex Red™ and 0.1 unit/ml horseradish peroxidase. The rate at which Amplex Red™ fluorescence increased (Ex: 485/Em: 510), over a 4 hour period, was measured using a Synergy HT plate reader (Bio Tek Instruments, Inc.). Values were normalized for cellular protein.

Measurement of the Steady State H2O2 Concentrations

The steady state H2O2 concentrations were measured by determining the rate of catalase inactivation [19]. Following treatment, 20 mM 3-amino-2,4,5-triazole was added to the cell cultures. In the presence of H2O2, 20 mM was sufficient to inactivate catalase in a 6 hour time course, suggesting that 20 mM aminotriazole is saturating. Samples were harvested at intervals over a 6 hour time course. Catalase activity was measured in each sample as previously described [13]. Activity was normalized for cellular protein. The rate of catalase inactivation was used to calculate the steady state H2O2 concentrations.

Glutathione and Glutathione Disulfide Measurements

Glutathione (GSH) and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) were measured using the Bioxytech GSH/GSSG 412 kit (Oxis Research, Portland, OR) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To deplete glutathione levels, cells were pretreated with 0.5 μM buthionine sulphoximine (BSO) for 4 hours in WEHI7.2 cells, and 5 μM BSO for 8 hours in Molt 4 and Jurkat cells. Values were normalized for cellular protein. The GSH levels were also measured in the cell-free system using the same kit.

Immunoblots

To determine the protein expression of catalase and glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1), 10 or 100 μg, respectively, of clarified total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE. Blots were probed for catalase using a 1:7,500 dilution of anti-catalase (AbCam, Cambridge, MA), or for GPX1 at a 1:2,000 dilution of anti-GPX1 (Lab Frontiers, Seoul, Korea). Proteins were detected by incubating with a 1:2,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase linked anti-rabbit Ig (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and visualized by chemiluminescence. To determine protein glutathionylation, 25 μg protein from clarified total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE. Blots were probed for glutathionylation using a 1:2,500 dilution of anti-GSH antibody (Virogen, Watertown, MA). Blots were also probed with anti-β actin (AbCam, Cambridge, MA) at a 1:50,000 dilution followed by a 1:2,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-mouse Ig, as a loading control (GE Healthcare). To visualize multiple bands on the same blot, blots were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce) before being probed with a new antibody.

NF-κB Glutathionylation

500 μg of protein from cellular extracts were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg of anti-p65 NF-κB (AbCam) or anti-p50 NF-κB (Upstate, Billerica, MA). Protein A-agarose beads (Invitrogen) were added and the solution was incubated at 4°C for 1 hour on a rocker platform. The pellets were collected by centrifugation at 600 x g for 2 minutes at 4°C and washed three times in CHAPS (1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; 1M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1M NaCl) buffer. After a final wash, the pellets were resuspended in SDS lysis buffer and loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel for immunoblot analysis. Blots were probed with an anti-GSH antibody (Virogen) to determine if they are glutathionylated, or with p50/p65 antibodies to control for loading.

Reporter Assay for NF-κB Activity

Cells were transiently transfected with 2 μg of plasmid containing the NF-κB promoter fused to the firefly luciferase gene (Promega, Madison, WI) or 2 μg of empty luciferase construct (Promega) using the Amaxa Nucleofactor™ II kit (Amaxa Gmbh). Cells were allowed to recover for 24 hours and then treated with indicated drug combinations and harvested. Relative luciferase activity was measured with a luciferase assay system (Promega) using a Synergy HT plate reader (Bio Tek Instruments, Inc.). Luciferase activity was normalized for transfection efficiency using β-galactosidase activity, which was measured using a FluoReporterR LacZ/β-galactosidase quantitation kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and normalized for cellular protein. Luciferase activity was assessed as relative light units and used as an indicator of transcriptional induction of NF-κB.

Statistics

Means were compared using student’s t-tests with the algorithm in Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Means were considered significantly different when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

MnTE-2-PyP5+ potentiates dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells

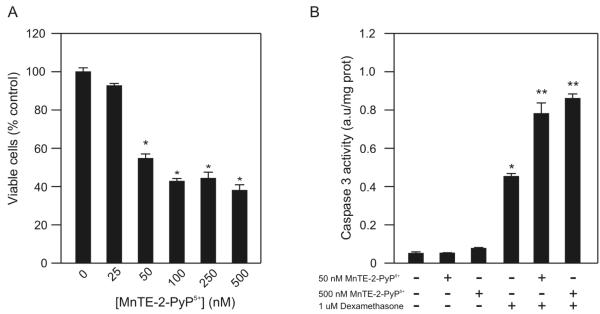

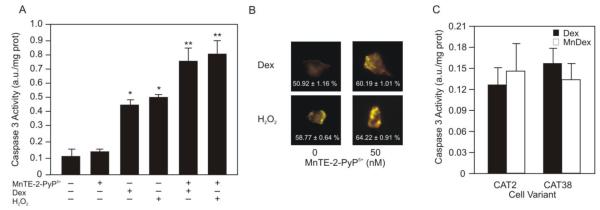

Previously, our laboratory reported that MnTE-2-PyP5+ causes a concentration-dependent inhibition of WEHI7.2 cell growth [3]. MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in a concentration and time dependent manner in WEHI7.2 cells [3]. After these findings were published, our laboratory obtained a new preparation of MnTE-2-PyP5+ with a higher specific activity. To confirm that this preparation generates the same effect in WEHI7.2 cells, we measured cell growth and apoptosis. Treatment with 50 nM to 500 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ inhibited WEHI7.2 cell growth (Figure 1A); neither 50 nor 500 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ alone induced WEHI7.2 cell apoptosis (Figure 1B). In combination with dexamethasone, however, 50 and 500 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ increased caspase 3 activity in WEHI7.2 cells (Figure 1B). Our findings confirm that MnTE-2-PyP5+ inhibits WEHI7.2 cell proliferation and enhances glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.

Figure 1.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ sensitizes WEHI7.2 cells to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. A. Percentage of viable WEHI7.2 cells in culture after a 12 hour treatment with 25-1000 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+. Values are the mean of triplicate cultures + S.E.M. Values in the untreated cultures were set to 100%. B. Caspase 3 activity after treatment with 50 nM or 500 μM MnTE-2-PyP5+, 1 μM dexamethasone, and MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone for 12 hours in WEHI7.2 cells. The values have been corrected for the caspase 3 activity in vehicle-treated cell cultures. Values represent the mean + S.E.M (n=3). * denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated (Control) cells; ** denotes significantly different from dexamethasone-treated, porphyrin-only treated and control cells (p ≤ 0.05).

Using a mathematical synergy model (described in [14]) we tested whether MnTE-2-PyP5+ synergizes with dexamethasone to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. The model predicts that if the porphyrin is working alongside dexamethasone in an additive manner, 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone would decrease the percentage of viable cells by 77%. In combination with dexamethasone, the porphyrin decreased cell viability more than 87.5 ± 3.3%. Similar results were seen at other porphyrin concentrations (data not shown). Since the actual response exceeds the predicted values, these findings indicate that MnTE-2-PyP5+ synergizes with dexamethasone to enhance WEHI7.2 cell death.

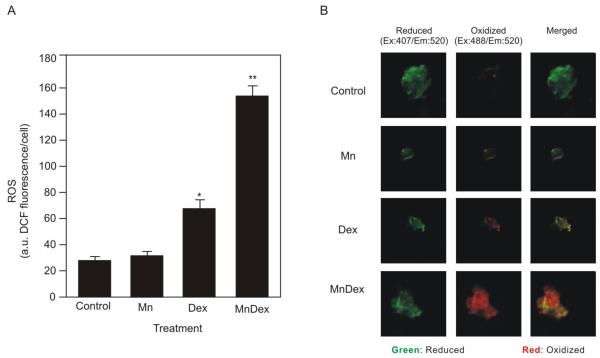

MnTE-2-PyP5+ augments dexamethasone-induced ROS and oxidation of the redox environment

In WEHI7.2 cells, dexamethasone treatment increases intracellular H2O2 and oxidizes the cells’ redox environment. H2O2 is an essential signal for dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in WEHI7.2 cells [17]. MnTE-2-PyP5+ may enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis by acting as a pro-oxidant and augmenting dexamethasone-induced oxidative stress in WEHI7.2 cells. To test this hypothesis we used DCF fluorescence to measure the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+, in combination with dexamethasone, to increase the overall levels of ROS. As shown in Figure 2A, treatment with MnTE-2-PyP5+ alone did not increase ROS in the cells. Dexamethasone treatment increased the overall levels of ROS. The combination of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone caused the greatest increase in ROS.

Figure 2.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced ROS levels and oxidation of the redox environment. A. Overall ROS levels (DCF fluorescence) in WEHI7.2 cells pretreated with 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ for 2 hours followed by 1 μM dexamethasone treatment (MnDex) for 8 hours compared to dexamethasone-only treated cells (Dex). Overall ROS of control treated and MnTE-2-PyP5+ only treated cells are included for reference. Values represent the mean + S.E.M (n=6). .* denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated (Control) cells; ** denotes significantly different from dexamethasone-treated, porphyrin-only treated, and control cells (p ≤ 0.05) B. Changes to the cytosolic redox environment following dexamethasone treatment in WEHI7.2 cells compared to cells pretreated with 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ for 2 hours followed by an 8 hour 1 μM dexamethasone treatment. Changes to the cytosolic redox environment of vehicle-treated and MnTE-2-PyP5+ only treated cells were included as controls. Images are of individual cells transfected with roGFP2. The green signal is the intensity of the reduced roGFP2. The red signal is of the oxidized roGFP2. Merged images are included to show which redox state dominates in each of the treatments (n=24).

As a second measure of oxidative stress, we used a redox-sensitive GFP probe, roGFP2 [16] to determine whether MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced oxidation of the redox environment. The roGFP2 probe contains a GFP molecule with redox active cysteines that excite at different wavelengths depending on the oxidation state of the roGFP2. Figure 2B shows images of the relative amount of oxidized and reduced GFP in representative cells for each treatment. In control cells treated with vehicle alone, 14.03 ± 1.46% of the roGFP2 was oxidized. MnTE-2-PyP5+ treatment alone did not oxidize the redox environment; 16.11 ± 1.31% of the roGFP2 was oxidized. In the presence of dexamethasone, the amount of oxidized roGFP2 increased to 54.05 ± 1.04%. Combining dexamethasone with MnTE-2-PyP5+ increased the relative amount of roGFP2 in the oxidized state to 61.39 ± 1.55%. Overall, these data indicate that in combination with dexamethasone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ acts as a pro-oxidant and increases oxidative stress over that caused by dexamethasone alone.

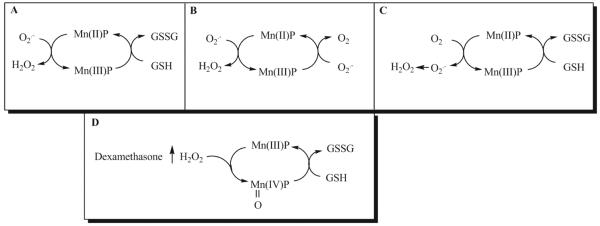

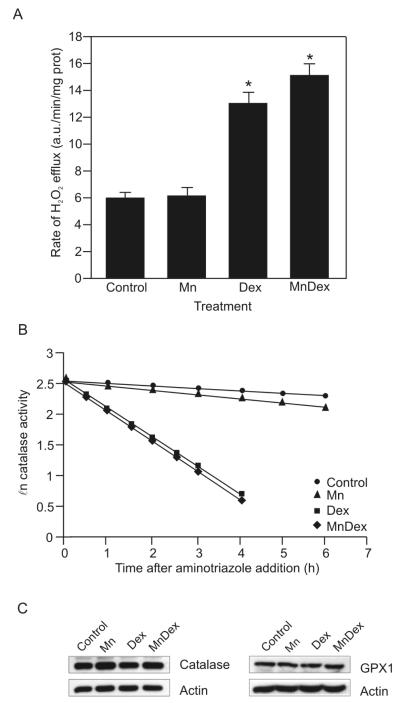

MnTE-2-PyP5+ does not increase H2O2 levels in WEHI7.2 cells treated with dexamethasone

MnTE-2-PyP5+ can act as a pro-oxidant by acting as a redox cycling agent. MnTE-2-PyP5+ generates H2O2 when the porphyrin redox cycles between the Mn(II) and Mn(III) redox states [20]. In these states MnTE-2-PyP5+ acts either as an SOD mimetic, superoxide reductase, or cycles with cellular reductants to generate H2O2 (Figure 10A, B, C). If MnTE-2-PyP5+ is cycling between the Mn(II) and Mn(III) states in the WEHI7.2 cells, we would predict that MnTE-2-PyP5+ increases the H2O2 above that in cells treated with dexamethasone. We measured H2O2 levels due to MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone treatment in WEHI7.2 cells using two different approaches. We first measured the efflux of H2O2 using the fluorescent probe Amplex Red™. This compound is impermeable to the cell membrane [18]. Amplex Red™ fluoresces when it is oxidized by extracellular H2O2 [18]. Since H2O2 readily diffuses across cell membranes, Amplex Red™ fluorescence is a good indicator of the H2O2 inside the cells [18]. Compared to control cells, MnTE-2-PyP5+ alone did not augment H2O2 levels (Figure 3A). Consistent with our previous data [17], dexamethasone treatment for 8 hours enhanced the H2O2 efflux in WEHI7.2 cells. However, there was not a difference in H2O2 efflux between dexamethasone-treated cells and cells treated with the combination of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone.

Figure 10.

Pro-oxidant reactions for MnTE-2-PyP5+. MnTE-2-PyP5+ can act as a pro-oxidant by cycling between the Mn(III) and Mn(II) redox states. In these states MnTE-2-PyP5+ can act as a superoxide dismutase (A), superoxide reductase (B) or it will cycle with reducing agents, to generate H2O2 (C). In our system, MnTE-2-PyP5+ does not increase H2O2 levels, suggesting that it is not cycling between the Mn(III)P and Mn(II)P redox couples. MnTE-2-PyP5+ can be oxidized to O=MnTE-2-PyP4+ by H2O2. The porphyrin is then reduced back to the Mn(III) state by small molecule reductants such as glutathione (GSH). Dexamethasone increases H2O2 levels in WEHI7.2 cells. Thus, MnTE-2-PyP5+ could be oxidized to the O=Mn(IV)P state. O=MnTE-2-PyP4+ cycles with GSH; thereby depleting GSH and increasing glutathione disulfide (GSSG) levels to increase oxidative stress in WEHI7.2 cells (D).

Figure 3.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ does not augment dexamethasone-induced H2O2 levels. Cells were treated as in Figure 2. A. Rate of H2O2 efflux in WEHI7.2 cells measured by Amplex Red™ fluorescence. Values represent the mean + S.E.M (n=4). B. Plot of the ℓn catalase activity in the presence of 20 mM aminotriazole in control (●), MnTE-2-PyP5+-treated (▴), dexamethasone-treated (∎), and cells receiving the combination treatment (MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone) (◆). This is a representative experiment which has been replicated. The [H2O2]ss was calculated from the mean rate of catalase inactivation of four rate determinations. C. Representative immunoblots showing catalase and GPX1 protein expression in WEHI7.2 cells treated with a vehicle, MnTE-2-PyP5+, dexamethasone, or cells receiving the combination treatment. Representative actin immunoblots are shown to demonstrate similar loading. * denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated (Control) and porphyrin-only treated cells (p ≤ 0.05).

We next measured the steady state H2O2 levels ([H2O2]ss) following treatment, using the catalase inactivation assay described by Royall et al. [19]. The [H2O2] ss of control cells was 21.8 ± 3.5 pM (Figure 3B). Eight hours after the addition of MnTE-2-PyP5+, the [H2O2] ss was 21.7 ± 2.1 pM. Dexamethasone treatment for 8 hours increased the [H2O2] ss to 50.6 ± 2.2 pM. However, the combination treatment did not significantly augment dexamethasone-induced [H2O2]ss; the [H2O2]ss following combined treatment was 53.3 ± 1.8 pM, (p ≤ 0.05).

The overall level of H2O2 in a cell depends on generation and removal. Recent studies in our laboratory using WEHI7.2 cells to assess the importance of H2O2 for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis indicate that the main route of H2O2 catabolism in WEHI7.2 cells is via catalase [17]. WEHI7.2 cells have glutathione peroxidase (GPX); however, the levels and activity are low. One possible explanation of the above data is that MnTE-2-PyP5+ may be increasing H2O2 levels; however, the increase may go unnoticed because MnTE-2-PyP5+ may also be increasing the levels of catalase and GPX1 in WEHI7.2 cells. Neither MnTE-2-PyP5+, dexamethasone, nor the combination treatment altered catalase or GPX1 protein levels compared to vehicle-treated cells (Figure 3C). Taken together, these findings indicate that MnTE-2-PyP5+ does not potentiate dexamethasone-induced apoptosis by cycling between the Mn(II) and Mn(III) states and increasing intracellular H2O2.

Hydrogen peroxide generation is essential for MnTE-2-PyP5+ to cause apoptosis

To determine whether the H2O2 generated by dexamethasone is important for the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to induce apoptosis in lymphoma cells we substituted 25 nM H2O2 for the dexamethasone treatment and determined whether MnTE-2-PyP5+ was able to potentiate H2O2-induced apoptosis in WEHI7.2 cells. As shown in Figure 4A, the caspase 3 activity in cells treated with 25 nM H2O2 increased to the same extent as in cells treated with dexamethasone only. In combination with H2O2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ augmented the caspase 3 activity. Caspase 3 activity in the H2O2/MnTE-2-PyP5+ treated cells was similar to that in dexamethasone/MnTE-2-PyP5+ cells. We observed the same trend when we measured viable cells using an MTS assay. In the presence of H2O2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ decreased the percentage of viable cells to the same extent as MnTE-2-PyP5+ combined with dexamethasone. The percentage of viable WEHI7.2 cells treated with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone was 40.0 ± 0.2%, and the percentage of viable WEHI7.2 cells in cultures treated with H2O2 and MnTE-2-PyP5+ was 42.5 ± 1.1%. As proof of principle, when we measured the oxidation state of the cells using the roGFP2 plasmid, the redox environment of WEHI7.2 cells treated with H2O2 and MnTE-2-PyP5+ was as oxidized as the redox environment of WEHI7.2 cells treated with the standard combination treatment (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Hydrogen peroxide is essential for MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. A. Caspase 3 activity of WEHI7.2 cells treated with MnTE-2-PyP5+, dexamethasone, 25 nM H2O2 and MnTE-2-PyP5+ or dexamethasone in combination with MnTE-2-PyP5+ or H2O2 for 12 hours. Values represent the mean + S.E.M (n=6). B. Changes to the cytosolic redox environment of WEHI7.2 cells treated with 25 nM H2O2 and MnTE-2-PyP5+, or with MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone. The redox environment of WEHI7.2 cells treated with H2O2 or dexamethasone alone are shown as controls. Images are of individual cells transfected with roGFP2. The percent oxidized is included in each image. (n=6). C. Caspase 3 activity of CAT2 and CAT38 cells pretreated with MnTE-2-PyP5+ for 2 hours followed by 12 hours of dexamethasone. Values represent the mean + S.E.M (n=3). * denotes significantly different from control or MnTE-2-PyP5+ treated cells. ** denotes significantly different from dexamethasone or H2O2 treated cells (p≤0.05).

The above findings suggest that the [H2O2]ss levels in the cell dictate the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone induced apoptosis. We tested this using WEHI7.2 cells that overexpress catalase (CAT38-1.4 fold increase; and CAT2-2 fold increase) [13]. These cells remove H2O2 more efficiently than WEHI7.2 cells; thus, in the presence of dexamethasone they do not experience an increase in H2O2 and their redox environment does not become oxidized [17]. The variant cells are also resistant to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. In CAT2 and CAT38 cells, MnTE-2-PyP5+ did not alter the percentage of viable cells in the presence of dexamethasone. Using an MTS assay, we found that the number of viable cells in dexamethasone-treated cultures was 100.3 ± 1.3% and 100.8 ± 1.5%, for CAT2 and CAT38 cells, respectively. In cultures treated with dexamethasone and MnTE-2-PyP5+, the number of viable cells was 102.0 ± 1.3% for CAT2 cells and 98.9 ± 0.9% for CAT38 cells. We confirmed these results by comparing caspase 3 activity in the variant cells treated with dexamethasone or the combination treatment. MnTE-2-PyP5+ did not cause apoptosis in the presence of dexamethasone in the variant cells as measured by caspase 3 activity (Figure 4C). Taken together the findings indicate that the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells depends on: 1) the intracellular levels of H2O2, and 2) the oxidation of the cellular redox environment.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ redox cycles with GSH

Glutathione (GSH) is a major determinant of the redox environment of the cell [21]. Several studies have shown a correlation between GSH depletion and the progression of apoptosis in lymphocytes [22-25]. In cell free studies, MnTE-2-PyP5+ has been shown to depend on small molecule reductants, such as glutathione for its ability to redox cycle [8,9,12]. To determine whether, in the presence of H2O2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ redox cycles with GSH we measured the ability of the porphyrin in combination with H2O2 to alter the levels of GSH in a cell free system. As shown in Table 1, in combination with H2O2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ decreased GSH in a dose and time dependent manner. Neither the porphyrin nor H2O2 alone decreased the levels of GSH. These findings suggest that: 1) H2O2 is important for the porphyrin’s ability to act as a pro-oxidant and; 2) MnTE-2-PyP5+ redox cycles with GSH.

Table 1.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ depletes glutathione levels in a cell-free system

| GSH (nmol) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 5 min | 30 min | 60 min |

| MnTE-2-PyP5+ | 2.76 ± 0.01 | 2.75 ± 0.02 | 2.74 ± 0.04 |

| MnTE-2-PyP5+ + 0.5 nM H2O2 | 2.76 ± 0.02 | 2.70 ± 0.02 | 2.48 ± 0.02* |

| MnTE-2-PyP5+ + 25 nM H2O2 | 2.69 ± 0.04 | 2.50 ± 0.04* | 2.39 ± 0.03* |

| MnTE-2-PyP5+ + 100 nM H2O2 | 2.37 ± 0.01* | 1.83 ± 0.06* | 1.71 ± 0.03* |

MnTE-2-PyP5+ depletes cytosolic GSH

A possible explanation for the observed increase in oxidative stress, therefore, is that in combination with dexamethasone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ acts as a pro-oxidant by redox cycling and depleting GSH. We tested this hypothesis by measuring GSH levels in WEHI7.2 cells treated with the porphyrin, dexamethasone, and the porphyrin combined with dexamethasone. As shown in Table 2, in WEHI7.2 cells, 8 hour treatment with 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ significantly decreased GSH by nearly 42% compared to vehicle-treated cells. Treatment with 1 μM dexamethasone also depleted GSH levels, but only by 21%. The combination of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone depleted GSH by 61%, increased GSSG, and modified the 2GSH:GSSG ratio.

Table 2.

Glutathione/glutathione disulfide redox couple in WEHI7.2 cells

| Treatment | 2 GSH (nmol/mg prot) |

GSSG (nmol/mg prot) |

2 GSH/GSSG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 52.7 ± 1.25 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 398.94 ± 61.48 |

| 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ | 30.8 ± 2.01* | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 113.26 ± 28.81* |

| 1 μM dexamethasone | 41.8 ± 1.15* | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 214.55 ± 15.60* |

| 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ + 1 μM dexamethasone | 20.7 ± 0.46* | 1.69 ± 0.04 | 13.06 ± 0.74* |

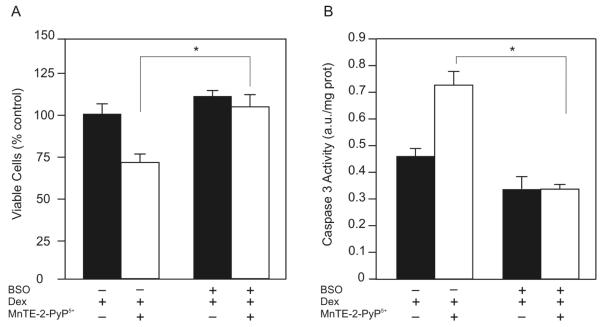

Glutathione is necessary for the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis

To determine whether GSH is required for MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis we measured the effect of the combination treatment on cell viability after depleting cytosolic GSH. Pretreating WEHI7.2 cells with 0.5 μM BSO, a GSH synthesis inhibitor [18], decreased cellular GSH from 28.71 ± 0.65 nmol/mg protein in control cells to 2.83 ± 0.92 nmol/mg protein in cells treated with BSO. GSH remained low in the presence of MnTE-2-PyP5+ (4.17 ± 0.64 nmol/mg protein), dexamethasone (5.85 ± 0.22 nmol/mg protein), or MnTE-2-PyP5+ combined with dexamethasone (6.41 ± 0.56 nmol/mg protein). BSO pretreatment inhibited the porphyrin’s ability to decrease the number of viable cells (Figure 5A). Using dexamethasone-treated WEHI7.2 cells as the control absorbance, set at 100.0 ± 2.8%, the MTS absorbance for cells pretreated with BSO and receiving MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone was 103.9 ± 3.1%. BSO pretreatment also inhibited the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced caspase 3 activity (Figure 5B). In both the MTS and caspase 3 activity assays, BSO treatment did not affect the dexamethasone response. These findings indicate that glutathione is essential for the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells.

Figure 5.

Glutathione depletion inhibits the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. A. Relative number of viable WEHI7.2 cells in culture after a 2 hour pretreatment with 0.5 μM BSO followed by a 12 hour treatment with MnTE-2-PyP5+and dexamethasone. Values for WEHI7.2 cells treated with dexamethasone alone were set to 100%. Values are the mean of triplicate cultures + S.E.M. B. Caspase 3 activity of WEHI7.2 cells pretreated with 0.5 μM BSO for 2 hours followed by 50 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ and 1 μM dexamethasone for 12 hours. The values have been corrected for the caspase activity in vehicle treated cultures. Values represent the mean + S.E.M (n=6). * denotes significantly different from MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone-treated cells (p ≤ 0.05).

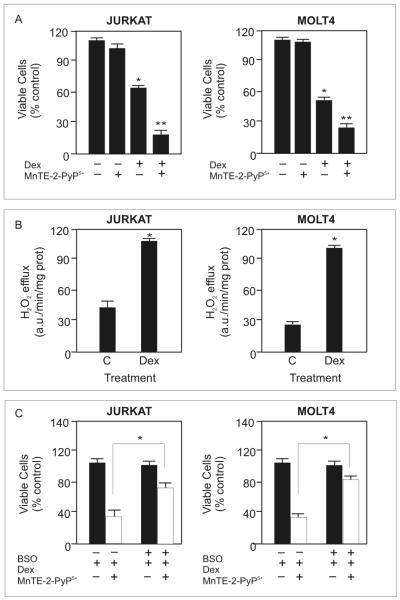

MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in malignant human T-cells

To determine whether MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in malignant human lymphoid cells we measured the percent viable cells in Molt4 and Jurkat cells, two human T-cell leukemia cell lines, after treatment with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone. MnTE-2-PyP5+ treatment alone did not affect cell viability, dexamethasone decreased cell viability approximately 50% in both cell types, and combining MnTE-2-PyP5+ with dexamethasone decreased the viable cells more than dexamethasone treatment alone (Figure 6A). Our findings suggest that MnTE-2-PyP5+ also synergizes with dexamethasone in the human cell lines. If the porphyrin is working alongside dexamethasone in an additive manner, the mathematical synergy model predicts that at the measured doses (500 nM MnTE-2-PyP5+ and 250 or 500 μM dexamethasone, for Jurkat and Molt4 cells, respectively) the combination treatment would decrease the percentage of viable cells to 84.6% and 83.7% in Jurkat and Molt4 cells respectively. However, when MnTE-2-PyP5+ is used in combination with dexamethasone, the porphyrin decreased cell viability to 25.9 ± 4.2% and 29.7 ± 3.5% in Jurkat and Molt4 cells respectively. This suggests that MnTE-2-PyP5+ synergizes with dexamethasone to enhance cell death in malignant human T-cells. We tested several concentrations of dexamethasone and MnTE-2-PyP5+ in these cells; a plot of the predicted response and actual values are included as supplementary data (Supplementary Figure 1). At all concentrations tested, the porphyrin exceeded the response predicted by the mathematical model, indicating that the porphyrin synergizes with dexamethasone to increase apoptosis in malignant human T-cells.

Figure 6.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in malignant human T-cells. A. Relative number of viable Molt4 and Jurkat cells after treatment with 0.5 μM MnTE-2-PyP5+ and 500 μM or 250 μM dexamethasone, respectively, for 48 hours. * denotes significantly different form control treated cells; ** denotes significantly different from dexamethasone-treated cells (p≤ 0.05). B. Rate of H2O2 efflux after 24 hours of dexamethasone treatment in Molt4 and Jurkat cells measured by Amplex Red™ fluorescence. * denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated cells (p≤ 0.05). C. Relative number of viable cells in culture after pretreating Molt4 and Jurkat cells with 5 μM BSO for 8 hours followed by treatment with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone as in A for 24 hours. Values for cells treated with dexamethasone alone were set to 100%. * denotes significantly different form MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone-treated cells (p≤ 0.05). For all experiments, values are the mean + S.E.M (n=3).

H2O2 is an important signal for the porphyrin to act as a pro-oxidant. We determined whether dexamethasone treatment increased H2O2 levels in Molt4 and Jurkat cells. Using Amplex Red™, we showed that 24 hour treatment with dexamethasone also increased H2O2 levels in these cells (Figure 6B). In Molt4 cells, the level of H2O2 increased approximately 4-fold and in the Jurkat cells approximately 2.5-fold.

GSH is also important for the porphyrin’s ability to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in WEHI7.2 cells. We determined whether GSH is important in Molt4 and Jurkat cells by measuring the effect of the combination treatment on cell viability in the absence of cytosolic GSH. Pretreating Molt 4 and Jurkat cells with 5 μM BSO, decreased cellular GSH in Molt4 cells from 26.0 ± 0.1 nmol/mg protein to 0.7 ± 0.9 nmol/mg protein and from 29.9 ± 0.5 nmol/mg protein to 1.3 ± 0.8 nmol/mg protein in Jurkat cells. BSO pretreatment inhibited the porphyrin’s ability to decrease the number of viable cells (Figure 6C). Using dexamethasone-treated cells as the control absorbance, set at 100.0 ± 1.1% for Molt4 cells and 100.0 ± 0.8% for Jurkat cells, the MTS absorbance for cells pretreated with BSO and receiving MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone was 81.2 ± 0.5% for Molt4 cells and 84.7 ± 0.7% for Jurkat cells. BSO pretreatment did not affect the dexamethasone response. These findings indicate that GSH is partially responsible for the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in malignant human T-cells. Taken together, these findings suggest that the porphyrin enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis via a similar mechanism in malignant human T-cells.

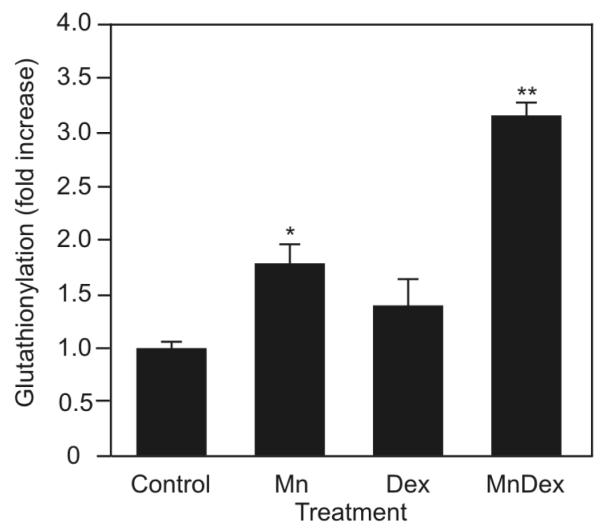

MnTE-2-PyP5+-glutathionylates redox sensitive proteins

GSH is important for the porphyrin’s ability to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in WEHI7.2 and malignant human lymphocytes. Thus, it is likely that glutathionylation of critical target proteins may contribute to the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. Protein glutathionylation, a reversible post-translational modification in which glutathione forms mixed disulfides with protein sulfhydryl groups is regulated by the GSH:GSSG redox couple [21]. Glutathionylation occurs at high frequency in the presence of high cellular GSSG levels and in an oxidized intracellular redox environment [26]. Given that MnTE-2-PyP5+, in combination with dexamethasone, oxidizes the redox environment of WEHI7.2 cells and increases GSSG levels we tested whether this combination caused protein glutathionylation in the WEHI7.2 cells. As shown in Figure 7 and in Supplementary Figure 2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ treatment alone resulted in glutathionylation of intracellular proteins, even more so than dexamethasone alone. The most pronounced effect was measured when cells were treated with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone. The combination treatment enhanced protein glutathionylation 2.5-fold more than dexamethasone treatment alone.

Figure 7.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ glutathionylates redox sensitive proteins. Quantification of the overall protein glutathionylation in WEHI7.2 cells treated with MnTE-2-PyP5+ (Mn), dexamethasone (D), or MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone (MnD) for 8 hours. * denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated (Control) cells; ** denotes significantly different from porphyrin-only treated or dexamethasone-only treated cells (p ≤ 0.05).

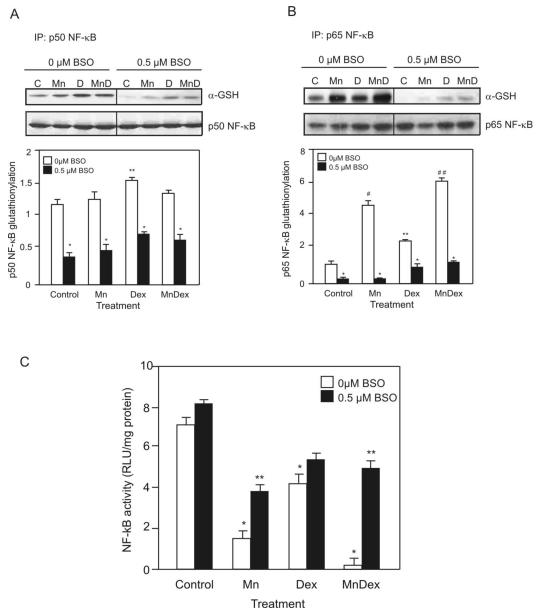

MnTE-2-PyP5+-glutathionylates NF-κB

Protein glutathionylation is a physiologically relevant mechanism for controlling the activity of redox-sensitive proteins associated with apoptosis [27-29]. NF-κB is a redox-sensitive transcription factor that regulates the expression of wide variety of anti-apoptotic genes [30]. Glucocorticoid inhibition of NF-κB is important for glucocorticoid-induced death in lymphoid cells [31,32]. NF-κB exists both as homo and heterodimers; however, the most common complex is the heterodimer formed by the p50 and p65 NF-κB family members. The activity of NF-κB depends on the oxidation state of cysteine residues on both proteins. The cysteines must be in a reduced state in order for NF-κB to bind DNA and to activate its transcriptional activity [33]. These residues, however, are surrounded by a cationic environment that makes the cysteines very reactive and susceptible to oxidation or glutathionylation [34,35].

We tested for glutathionylation of p50 and p65 in WEHI7.2 cells treated for 8 hours with dexamethasone in the absence or presence of MnTE-2-PyP5+. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated for p50 or p65 and then immunobloted using an anti-GSH antibody to measure their respective glutathionylation. Figure 8A demonstrates that only in cultures treated with dexamethasone, and dexamethasone in combination with MnTE-2-PyP5+ was glutathionylation of p50 increased. The combination treatment was not able to enhance dexamethasone-induced glutathionylation of p50. Treatment with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and MnTE-2-PyP5+ combined with dexamethasone increased glutathionylated p65 (Figure 8B). MnTE-2-PyP5+ increased p65 glutathionylation to nearly 3-fold over that in the vehicle-control. Dexamethasone treatment also increased glutathionylation of p65 but only to 1.5-fold the amount in the vehicle-control. The combination treatment enhanced p65 glutathionylation 3-fold over that induced by dexamethasone alone or 4.5-fold the value in the vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 8.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ glutathionylates NF-κB and inhibits its activity. A. Representative immunoblot comparing the glutathionylation of p50 NF-κB after treating cells with MnTE-2-PyP5+ (Mn), dexamethasone (D), or MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination (MnD) with dexamethasone for 8 hours to cells pretreated with 0.5 μM BSO for 2 hours and then treated with either MnTE-2-PyP5+, dexamethasone or the combination treatment. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated for p50 and then immunoblotted using an anti-GSH or p50 NF-κB antibody. Quantification of the representative immunoblots is also shown. Values are the mean of triplicate cultures + S.E.M. * denotes significantly different from non BSO-treated cells. ** denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated (Control) cells (p≤0.05). B. Representative immunoblots comparing the glutathionylation of p65 NF-κB after treating cells as in A. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated for p65 and then immunoblotted using an anti-GSH or p65 NF-κB antibody. Quantification of the respresentative Immunoblots is also shown. Values are the mean of triplicate cultures + S.E.M. * denotes significantly different from non-BSO-treated cells. ** denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated (Control) cells. # denotes significantly different from dexamethasone-only treated and control cells. ## denotes significantly different from porphyrin-only treated, dexamethasone-only treated and control cells (p≤0.05). C. Comparison of the NF-κB driven luciferase activity of WEHI7.2 cells treated with MnTE-2-PyP5+ (Mn), dexamethasone (Dex) or MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone (MnDex) for 8 hours to cells pretreated with 0.5 μM BSO for 2 hours and then treated with either MnTE-2-PyP5+, dexamethasone or the combination treatment. Values are the mean of triplicate cultures + S.E.M. * denotes significantly different from vehicle-treated (Control) cells; ** denotes significantly different from BSO pretreated cells (p ≤ 0.05).

BSO pretreatment attenuated the ability of the porphyrin, in combination with dexamethasone, to glutathionylate p50 and p65 (Figures 8A and B). After BSO pretreatment, the amount of glutathionylated p50 decreased in the vehicle-treated and MnTE-2-PyP5+-treated cells by 66.1 ± 1.1%. The levels of glutathionylated p50 were slightly higher in cells treated with dexamethasone and MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone; the treatments inhibited p50 glutathionylation by 56.2 ± 1.6%. In the case of p65, BSO pretreatment decreased p65 glutathionylation by: 80.3 ± 1.0% in vehicle-treated cells; 98.0 ± 0.6% in MnTE-2-PyP5+ treated cells; 53.6 ± 2.1% in dexamethasone-treated cells; and 84.9 ± 0.8% in cells treated with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone.

MnTE-2-PyP5+-induced glutathionylation inhibits NF-κB activity

As a single agent, or in combination with dexamethasone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ treatment significantly inhibited NF-κB activity (Figure 8C). MnTE-2-PyP5+ treatment alone decreased NF-κB luciferase activity by 6-fold compared to vehicle-treated cells. Dexamethasone treatment alone induced a 2-fold decrease in NF-κB luciferase activity. The largest decrease in NF-κB luciferase activity was due to treatment with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone; the combination treatment nearly inhibited NF-κB activity completely. The activity of NF-κB correlates with the glutathionylation of the p65 NF-κB subunit (Figure 7B), suggesting that the glutathionylation of p65 inhibits NF-κB activity. BSO pretreatment did not affect dexamethasone’s ability to inhibit NF-κB activity. On the other hand, BSO pretreatment inhibited the ability of the porphyrin and the combination treatment to inhibit NF-κB activity. Taken together, the data suggest that glutathionylation is an important mechanism through which MnTE-2-PyP5+ and the combination treatment regulate NF-κB activity.

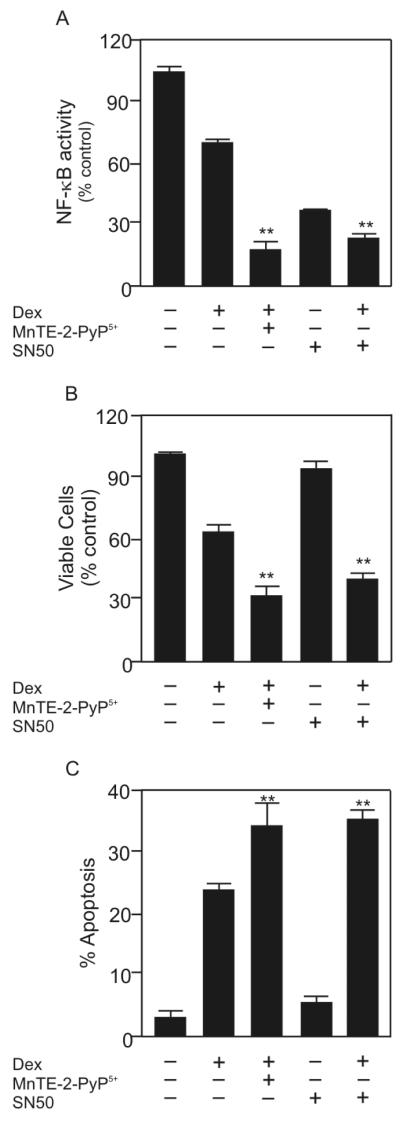

MnTE-2-PyP5+ inhibits NF-κB activity to potentiate dexamethasone-induced apoptosis

To determine whether NF-κB inhibition accounts for the increase in apoptosis seen by the dexamethasone/MnTE-2-PyP5+ combination, we tested whether an NF-κB inhibitor could substitute for MnTE-2-PyP5+. SN50 is a small inhibitory peptide that prevents NF-κB from binding to DNA, and thereby inhibits NF-κB activity [36]. We measured the ability of 10 μM SN50 to inhibit NF-κB activity and enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in WEHI7.2 cells. The MnTE-2-PyP5+/dexamethasone combination inhibited NF-κB activity more than 75% in WEHI7.2 cells. Treatment with SN50 alone inhibited NF-κB activity approximately 60%. When WEHI7.2 cells were treated with dexamethasone and SN50, the NF-κB activity decreased to the same amount as cells treated with MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone (Figure 9A), suggesting that MnTE-2-PyP5+ can inhibit NF-κB activity to the same extent as an established NF-κB inhibitor.

Figure 9.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ inhibits NF-κB activity to potentiate dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. A. Comparison of the NF-κB driven luciferase activity of WEHI7.2 cells treated with dexamethasone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone, SN50, or SN50 in combination with dexamethasone for 24 hours. B. Relative number of viable WEHI7.2 cells treated as in panel A. C. Percentage of WEHI7.2 cells positive for annexin V and negative for 7-AAD. Cells were treated as in panel A. Values are the mean of triplicate cultures + S.E.M. ** denotes that the values are statistically similar (p ≤ 0.05).

To confirm that SN50, in combination with dexamethasone, decreased the number of viable cells to the same extent as MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone we measured cell viability by MTS (Figure 9B). Our results demonstrate that SN50 is not toxic as a single agent in WEHI7.2 cells. However, when SN50 is used in combination with dexamethasone, the percent viable cells remaining in culture is only 24.7 ± 1.4%. The standard combination, MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone, decreased the percent live cells in culture to 29.4 ± 0.2%.

In combination with dexamethasone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ also increased apoptosis to the same extent as SN50 combined with dexamethasone in WEHI7.2 cells (Figure 9C). The percentage of apoptotic cells after MnTE-2-PyP5+/dexamethasone treatment was approximately 35.0 ± 4.2%. In comparison, 36.9 ± 3.5% WEHI7.2 cells underwent apoptosis following treatment with SN50 and dexamethasone. Taken together, these findings suggest that MnTE-2-PyP5+, in combination with dexamethasone, targets NF-κB to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis.

Discussion

Our studies indicate that the manganese porphyrin, MnTE-2-PyP5+ functions as a pro-oxidant to potentiate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells. Traditionally, the literature has suggested that manganese porphyrins function as SOD mimetics, due to their ability to scavenge O2•-. The physical and chemical properties of manganese porphyrins, however, suggest that the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to act as an SOD mimetic is just one of several activities with potential biological effects. In this study we show that, in combination with glucocorticoids, MnTE-2-PyP5+ altered the 2GSH:GSSG redox couple to increase dexamethasone-induced oxidative stress. The ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to redox cycle with GSH was essential for the porphyrin’s ability to enhance glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in WEHI7.2 and malignant human lymphoid cells. In the presence of dexamethasone, the porphyrin promoted protein glutathionylation, in particular of the p65 NF-κB subunit, inhibited NF-κB activity, and enhanced apoptosis.

In WEHI7.2 cells, MnTE-2-PyP5+ did not potentiate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by acting as an SOD mimetic. Studies done in cell free systems have shown that the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to act as an SOD mimetic depends on the oxidation state of the manganese at the center of the porphyrin ring [5,37,38]. The manganese can access four oxidation states in-vivo: Mn(II); Mn(III); O=Mn(IV); and O=Mn(V). In cell-free systems, manganese porphyrins are most stable in the Mn(III) oxidation state [6]. MnTE-2-PyP5+ acts as an SOD mimetic by redox cycling between the Mn(III) and Mn(II) redox states (Figure 10A). In these states, MnTE-2-PyP5+ can also act as a superoxide reductase (Figure 10B) or it can cycle with reducing agents (Figure 10C), to generate H2O2. A recent study demonstrated that MnTE-2-PyP5+ redox cycles within the Mn(III) and Mn(II) states in the presence of ascorbate, a reducing agent, and generates H2O2 [20]. In the WEHI7.2 cells however, MnTE-2-PyP5+ in combination with dexamethasone does not increase the levels of H2O2, suggesting that in our system the porphyrin is not redox cycling between the Mn(III) and Mn(II) states to act as a pro-oxidant.

In the presence of H2O2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ can undergo oxidation to the O=Mn(IV) state [39]. This species, by itself, is highly oxidizing and can cause damage if it is not reduced by cellular reductants. In WEHI7.2 cells, MnTE-2-PyP5+ augmented dexamethasone-induced oxidation of the redox environment when it was combined with dexamethasone or with H2O2. Cell-free studies have shown that MnTE-2-PyP5+ can be oxidized to O=Mn(IV) in the presence of H2O2 [6]. Thus, it is possible that in cells and in the presence of dexamethasone or an environment with increased H2O2, the active site manganese in MnTE-2-PyP5+ is oxidized to the O=Mn(IV) state. When it is oxidized, MnTE-2-PyP5+ relies on the reducing power of glutathione and other small molecule reductants to reduce the active site manganese back to the Mn(III) state (Figure 10D). In the present study, we showed that in the presence of low concentrations of H2O2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ depletes GSH in a cell-free system. In the absence of MnTE-2-PyP5+, H2O2 alone was not sufficient to decrease GSH levels. These data are consistent with MnTE-2-PyP5+ cycling between the O=Mn(IV) and Mn(III) redox states and using reducing equivalents from GSH. In WEHI7.2 cells, MnTE-2-PyP5+ combined with dexamethasone depletes cellular GSH, increases cellular GSSG, and alters the glutathione redox couple. Depleting GSH may enhance the probability that O=MnTE-2-PyP4+ can act as a pro-oxidant, and potentiate dexamethasone-induced oxidative stress in lymphoma. In summary, MnTE-2-PyP5+ may act as a pro-oxidant and deplete glutathione levels in lymphoma through two redox couples: Mn(III)P/Mn(II)P but also the O=Mn(IV)P/ Mn(III)P redox couple. The data obtained in this study indicate that MnTE-2-PyP5+ does not enhance the H2O2 levels generated by dexamethasone, and therefore favors the involvement of the O=Mn(IV)P/Mn(III)P redox couple (Figure 10).

These data suggest that MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone rely on different mechanisms to induce oxidative stress in lymphoma cells. The ability to induce two forms of oxidative stress allows MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone to synergize and enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. In our system, dexamethasone treatment increases the intracellular H2O2 levels. Removal of H2O2 prevents glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, suggesting that H2O2 is an important signal for dexamethasone-induced apoptosis [17]. The increase in H2O2 results in a slight decrease in intracellular GSH. Whether the small decrease in GSH is required for dexamethasone to induce apoptosis is unknown. However, a further decrease in GSH via BSO treatment did not enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis, suggesting that dexamethasone does not work just through oxidation of GSH. On the other hand, MnTE-2-PyP5+ treatment does not increase H2O2 and does not induce apoptosis as a single agent. Instead, MnTE-2-PyP5+ depends on the H2O2 produced by dexamethasone and on GSH to enhance apoptosis. Our findings suggest that MnTE-2-PyP5+ uses H2O2 and GSH to redox cycle and increase oxidative stress.

In combination with dexamethasone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ induces protein glutathionylation in WEHI7.2 cells. Protein glutathionylation is a reversible, post-translational modification of cysteine residues found on redox-sensitive proteins. Protein glutathionylation is promoted by changes to the intracellular GSH:GSSG levels. At high concentrations, GSGG will bind to protein cysteines and form a mixed disulfide. One of the major functions of protein glutathionylation is to act as a redox signal that regulates protein function. Large scale glutathionylation of proteins likely results in the inactivation of critical survival proteins.

The mechanism by which MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells involves inhibition of NF-κB through glutathionylation. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that glutathionylation of NF-κB inhibits its activity [26,28,35]. We found that MnTE-2-PyP5+ works in combination with dexamethasone to inhibit NF-κB and enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis to the same extent as dexamethasone and SN50, a small peptide inhibitor of NF-κB. All members of the NF-κB family contain a DNA binding domain within the conserved Rel homology domain. Several members contain an extra 300 amino acid sequence at the C-terminus that is important for transactivation [28,40]. The combination treatment of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and dexamethasone results in glutathionylation of p65, a member of the NF-κB family that has a transactivation domain and thus, can regulate transcription. Treatment with dexamethasone alone glutathionylates p50. This NF-κB family member does not have the transactivation domain; therefore, its primary function is to assist with DNA binding. Inhibiting p50 glutathionylation does not affect dexamethasone’s ability to inhibit NF-κB or to induce apoptosis. In contrast, preventing the ability of MnTE-2-PyP5+ plus dexamethasone to glutathionylate p65 restores NF-κB activity to dexamethasone levels and prevents MnTE-2-PyP5+ from enhancing dexamethasone-induced cell death. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that glutathionylation of the p65 NF-κB subunit is an important target for MnTE-2-PyP5+. While our data support glutathionylation as the mechanism by which MnTE-2-PyP5+ regulates NF-κB activity, we have not excluded the possibility that other posttranslational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation, ubiquitination, oxidation) are also playing a role. The exact mechanism by which glutathionylation inhibits NF-κB in lymphoma cells also remains to be elucidated.

Our data suggest that MnTE-2-PyP5+ has potential as a novel lymphoma therapeutic. In the presence of H2O2, MnTE-2-PyP5+ acts as a pro-oxidant and enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in murine and human cell lines. Alone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ is neither able to increase oxidative stress or induce apoptosis. These findings suggests that MnTE-2-PyP5+ is likely to enhance apoptosis in oxidized environments or in combination with other agents that increase H2O2 levels. GSH is also important for the porphyrin’s ability to glutathionylate p65 NF-κB and enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. Several hematological malignancies, including the activated B-cell like subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), overexpress NF-κB. Overexpression of NF-κB in these lymphomas is associated with a poor patient prognosis [41,42].We have shown that in combination with dexamethasone, MnTE-2-PyP5+ glutathionylated the p65 NF-κB subunit, inhibited NF-κB activity and enhanced apoptosis in lymphoma cells. Addition of MnTE-2-PyP5+ to the standard DLBCL treatment, which includes glucocorticoids, has the potential to improve treatment for this group of patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. MnTE-2-PyP5+ synergizes with dexamethasone to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in malignant human T-cells. The predicted line indicates the % viable cells if the effects of the two drugs are additive. The actual line shows the experimental % viable cells after treatment with varying concentrations of MnTE-2-PyP5+ or dexamethasone for 48 hours in Jurkat or Molt-4 cells.

Supplementary Figure 2. MnTE-2-PyP5+ glutathionylates redox sensitive proteins. Representative immunoblot comparing the overall protein glutathionylation after treating WEHI7.2 cells with MnTE-2-PyP5+ (Mn), dexamethasone (D), or MnTE-2-PyP5+ (MnD) for 8 hours. Actin is included as a loading control.

Highlights.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in lymphoma.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ acts as a pro-oxidant.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ depletes glutathione and glutathionylates proteins.

MnTE-2-PyP5+ glutathionylates and inhibits NF-κB to enhance apoptosis.

Glutathione is essential for MnTE-2-PyP5+ activity.

Acknowledgements

We thank: Junesse Farley and Paula Campbell for flow cytometry assistance; Dr. David Elliot for technical advice and assistance with the DeltaVision Restoration Microscopy System; Dr. James E. Remington for the roGFP2 plasmid; and David Stringer and Dr. Eugene Gerner for use of critical equipment. Funding for this study comes from the National Cancer Institute grants CA-71768 (M.M.B) and CA-09213 (M.C.J), Arizona Cancer Support grant CA-023074, Small Faculty Grant Program (M.E.T), and U.S. Department of Defense grant W81XWH-07-0550 (J.D.C). IBH acknowledges her General Research Funds.

Abbreviations

- BSO

buthionine sulfoxide

- CAT2, CAT38

WEHI7.2 clones overexpressing rat catalase

- cDCFH

5-(and 6)-carboxy-2′7′dichlorofluorescin

- DCFH/DCF

2′7′dichlorodihydrofluorescin/dichlorofluorescein

- DEX

dexamethasone

- GSH

glutathione

- [H2O2]ss

steady state hydrogen peroxide concentration

- MnTE-2-PyP5+

manganese tetrakis N-ethyl pyridium-2-yl porphyrin

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- [1].Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, Oken MM, Grogan TM, Mize EM, Glick JH, Coltman CA, Miller TP. Comparison of a Standard Regimen (CHOP) with Three Intensive Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1002–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304083281404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ghesquieres H, Ferlay C, Sebban C, Chassagne C, Carausu L, Gargi T, Favier B, Philip I, Blay JY, Biron P. Combination of rituximab with chemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Evaluation in daily practice before and after approval of rituximab in this indication. Hematol. Oncol. 2008;26:139–147. doi: 10.1002/hon.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jaramillo MC, Frye JB, Crapo JD, Briehl MM, Tome ME. Increased Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Expression or Treatment with Manganese Porphyrin Potentiates Dexamethasone-Induced Apoptosis in Lymphoma Cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5450–5457. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].DeFreitas-Silva G, Rebouτas J. l. S., Spasojevic I, Benov L, Idemori YM, Batinic-Haberle I. SOD-like activity of Mn(II) [beta]-octabromo-meso-tetrakis(N-methylpyridinium-3-yl)porphyrin equals that of the enzyme itself. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2008;477:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Faulkner KM, Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Stable Mn(III) porphyrins mimic superoxide dismutase in vitro and substitute for it in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23471–23476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I. Superoxide Dismutase Mimics: Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Therapeutic Potential. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2010;13:877–918. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hodge DR, Xiao W, Peng B, Cherry JC, Munroe DJ, Farrar WL. Enforced expression of superoxide dismutase 2/manganese superoxide dismutase disrupts autocrine interleukin-6 stimulation in human multiple myeloma cells and enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6255–6263. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Day BJ, Kariya C. A Novel Class of Cytochrome P450 Reductase Redox Cyclers: Cationic Manganoporphyrins. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;85:713–719. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ferrer-Sueta G, Hannibal L, Batinic-Haberle I, Radi R. Reduction of manganese porphyrins by flavoenzymes and submitochondrial particles: A catalytic cycle for the reduction of peroxynitrite. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2006;41:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ferrer-Sueta G, Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Fridovich I, Radi R. Catalytic scavenging of peroxynitrite by isomeric Mn(III) N-methylpyridylporphyrins in the presence of reductants. Chem. Res Toxicol. 1999;12:442–449. doi: 10.1021/tx980245d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Tse HM, Tovmasyan A, Rajic Z, St Clair DK, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW, Piganelli JD. Design of Mn porphyrins for treating oxidative stress injuries and their redox-based regulation of cellular transcriptional activities. Amino. Acids. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0603-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Fridovich I. Tetrahydrobiopterin rapidly reduces the SOD mimic Mn(III) ortho-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin. Free Radic. Biol Med. 2004;37:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tome ME, Baker AF, Powis G, Payne CM, Briehl MM. Catalase-overexpressing thymocytes are resistant to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis and exhibit increased net tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2766–2773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ahmad IM, Aykin-Burns N, Sim JE, Walsh SA, Higashikubo R, Buettner GR, Venkataraman S, Mackey MA, Flanagan SW, Oberley LW, Spitz DR. Mitochondrial and H2O2 Mediate Glucose Deprivation-induced Stress in Human Cancer Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:4254–4263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hanson GT, Aggeler R, Oglesbee D, Cannon M, Capaldi RA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ. Investigating mitochondrial redox potential with redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13044–13053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tome ME, Jaramillo MC, Briehl MM. Hydrogen peroxide signaling is required for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells. Free Radic. Biol Med. 2011;51:2048–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhou M, Diwu Z, Panchuk-Voloshina N, Haugland RP. A stable nonfluorescent derivative of resorufin for the fluorometric determination of trace hydrogen peroxide: applications in detecting the activity of phagocyte NADPH oxidase and other oxidases. Anal. Biochem. 1997;253:162–168. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Royall JA, Gwin PD, Parks DA, Freeman BA. Responses of vascular endothelial oxidant metabolism to lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992;294:686–694. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90742-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tian J, Peehl DM, Knox SJ. Metalloporphyrin synergizes with ascorbic acid to inhibit cancer cell growth through fenton chemistry. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2010;25:439–448. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2009.0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Franco R, Cidlowski JA. Apoptosis and glutathione: beyond an antioxidant. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1303–1314. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ghibelli L, Fanelli C, Rotilio G, Lafavia E, Coppola S, Colussi C, Civitareale P, Ciriolo MR. Rescue of cells from apoptosis by inhibition of active GSH extrusion. FASEB J. 1998;12:479–486. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hammond CL, Madejczyk MS, Ballatori N. Activation of plasma membrane reduced glutathione transport in death receptor apoptosis of HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004;195:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sato T, Machida T, Takahashi S, Iyama S, Sato Y, Kuribayashi K, Takada K, Oku T, Kawano Y, Okamoto T, Takimoto R, Matsunaga T, Takayama T, Takahashi M, Kato J, Niitsu Y. Fas-mediated apoptosome formation is dependent on reactive oxygen species derived from mitochondrial permeability transition in Jurkat cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:285–296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Franco R, Cidlowski JA. SLCO/OATP-like transport of glutathione in FasL-induced apoptosis: glutathione efflux is coupled to an organic anion exchange and is necessary for the progression of the execution phase of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29542–29557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gallogly MM, Mieyal JJ. Mechanisms of reversible protein glutathionylation in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007;7:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Velu CS, Niture SK, Doneanu CE, Pattabiraman N, Srivenugopal KS. Human p53 is inhibited by glutathionylation of cysteines present in the proximal DNA-binding domain during oxidative stress. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7765–7780. doi: 10.1021/bi700425y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Qanungo S, Starke DW, Pai HV, Mieyal JJ, Nieminen AL. Glutathione supplementation potentiates hypoxic apoptosis by S-glutathionylation of p65-NFkappaB. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18427–18436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Huang Z, Pinto JT, Deng H, Richie JP., Jr Inhibition of caspase-3 activity and activation by protein glutathionylation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;75:2234–2244. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kabe Y, Ando K, Hirao S, Yoshida M, Handa H. Redox regulation of NF-kappaB activation: distinct redox regulation between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2005;7:395–403. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Unlap T, Jope RS. Inhibition of NFkB DNA binding activity by glucocorticoids in rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;198:41–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11963-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Scheinman RI, Gualberto A, Jewell CM, Cidlowski JA, Baldwin AS., Jr Characterization of mechanisms involved in transrepression of NF-kappa B by activated glucocorticoid receptors. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:943–953. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mitomo K, Nakayama K, Fujimoto K, Sun X, Seki S, Yamamoto K. Two different cellular redox systems regulate the DNA-binding activity of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B in vitro. Gene. 1994;145:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pineda-Molina E, Klatt P, Vazquez J, Marina A, Garcia d. L., Perez-Sala D, Lamas S. Glutathionylation of the p50 subunit of NF-kappaB: a mechanism for redox-induced inhibition of DNA binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14134–14142. doi: 10.1021/bi011459o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Alisi A, Piemonte F, Pastore A, Panera N, Passarelli C, Tozzi G, Petrini S, Pietrobattista A, Bottazzo GF, Nobili V. Glutathionylation of p65NF-kappaB correlates with proliferating/apoptotic hepatoma cells exposed to pro- and anti-oxidants. Int. J Mol. Med. 2009;24:319–326. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lin YZ, Yao SY, Veach RA, Torgerson TR, Hawiger J. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kappa B by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14255–14258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pasternack RF, Banth A, Pasternack JM, Johnson CS. Catalysis of the disproportionation of superoxide by metalloporphyrins. III. J Inorg. Biochem. 1981;15:261–267. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)80161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gardner PR, Nguyen DD, White CW. Superoxide scavenging by Mn(II/III) tetrakis (1-methyl-4-pyridyl) porphyrin in mammalian cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;325:20–28. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Spasojevic I, Colvin OM, Warshany KR, Batinic-Haberle I. New approach to the activation of anti-cancer pro-drugs by metalloporphyrin-based cytochrome P450 mimics in all-aqueous biologically relevant system. J Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:1897–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Beinke S, Ley SC. Functions of NF-kappaB1 and NF-kappaB2 in immune cell biology. Biochem. J. 2004;382:393–409. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Davis RE, Brown KD, Siebenlist U, Staudt LM. Constitutive nuclear factor kappaB activity is required for survival of activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1861–1874. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Mitsiades C, Mitsiades N, Hayashi T, Munshi N, Dang L, Castro A, Palombella V, Adams J, Anderson KC. NF-kappa B as a therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16639–16647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. MnTE-2-PyP5+ synergizes with dexamethasone to enhance dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in malignant human T-cells. The predicted line indicates the % viable cells if the effects of the two drugs are additive. The actual line shows the experimental % viable cells after treatment with varying concentrations of MnTE-2-PyP5+ or dexamethasone for 48 hours in Jurkat or Molt-4 cells.

Supplementary Figure 2. MnTE-2-PyP5+ glutathionylates redox sensitive proteins. Representative immunoblot comparing the overall protein glutathionylation after treating WEHI7.2 cells with MnTE-2-PyP5+ (Mn), dexamethasone (D), or MnTE-2-PyP5+ (MnD) for 8 hours. Actin is included as a loading control.