Abstract

Understanding factors that promote or prevent adherence to recommended health behaviors is essential for developing effective health programs, particularly among lower-income populations who carry a disproportionate burden of disease. We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews (n=64) with low-income Black and Latina women who shared the experience of requiring diagnostic follow-up after having an abnormal screening mammogram. In addition to holding negative and fatalistic cancer-related beliefs, we found that the social context of these women was largely defined by multiple challenges and major life stressors that interfered with their ability to attain health. Factors commonly mentioned included competing health issues, economic hardship, demanding caretaking responsibilities and relationships, insurance-related challenges, distrust of healthcare providers, and inflexible work policies. Black women also reported discrimination and medical mistrust, while Latinas experienced difficulties associated with immigration and social isolation. These results suggest that effective health interventions not only address change among individuals, but must also change healthcare systems and social policies in order to reduce health disparities.

Keywords: Preventive care, Women’s Health, Health Disparities

Understanding and eliminating health disparities is a national public health priority.1–3 There are striking disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic position (SEP) for all leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the U.S., including cardiovascular disease and a range of cancers.4,5 The causes of health disparities are complex and not entirely understood, but likely result from a combination of individual and social contextual factors, defined here as structural forces that influence the texture of people’s day-to-day realities, including an array of social, cultural, and material resources.6 Health behaviors (e.g. physical activity, adherence to cancer screening and recommended follow-up) are important and potentially modifiable determinants of disease risk that certainly contribute to these inequities. In general, populations with lower levels of education and income and those from racial/ethnic minority groups consistently have poorer adherence to recommended public health guidelines and engage in more risk behaviors compared with higher SEP populations, and those from “majority” groups.4, 7–10 Yet the underlying causes of behavioral differences are not well-understood.

There is a growing recognition of the importance of understanding the role of broader social and cultural factors in shaping behaviors that reduce risk for disease and promote health.6,11–13 Yet few studies have provided an in-depth investigation of the larger social context in which health behaviors are embedded. An appreciation of the social and societal factors that promote or inhibit adherence to recommended health behaviors is critical to efforts to eliminate health disparities. A detailed investigation of social context will improve understanding of the determinants of deeply-rooted health disparities and inform development of effective policies and interventions for low-income populations.6,11

This paper provides an in-depth examination of factors that women report enable or impede their adherence to recommended health behaviors. In this study, women who experienced an abnormal screening mammogram requiring diagnostic follow-up care were interviewed about their daily lives and life history, in an effort to place this experience in a broader context. In a previous paper using data from this sample, we examined factors that were directly associated with whether women were compliant with recommended diagnostic follow-up (see Allen, Shelton et al., 2008).14 The focus of this paper is to provide a comprehensive and contextualized account of the broader factors that affected women’s abilities and motivation to adhere to recommended health behaviors. Qualitative methods are well-suited for conducting this research since they are ideal for: 1) explaining phenomena about which little is known; 2) understanding how people interpret and give meaning to the events and circumstances of their lives; and 3) exploring the social context in which behavior occurs.15

The aims of this paper are to: 1) investigate social contextual and psychosocial factors that influence the ability of lower-income Black and Latina women to carry out recommended health behaviors; 2) describe any relevant differences in social contextual and individual factors for Black and Latina women; and 3) identify potential implications for interventions, policies, and to generate hypotheses for further exploration in future research.

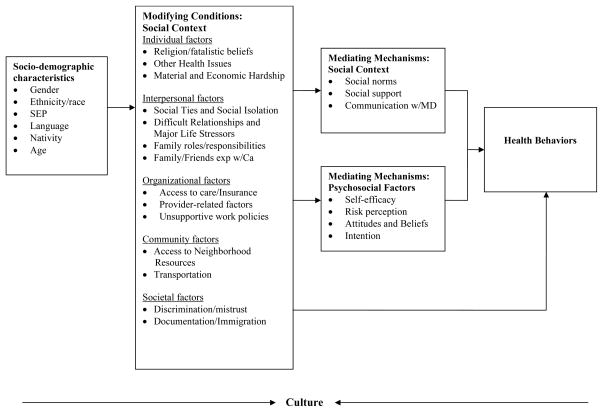

This research was informed by the social contextual framework,6 a conceptual framework that emphasizes the importance of viewing health behaviors within a social context, or the larger structural forces that determine the nature of people’s daily realities. Social contextual factors are seen as cutting across multiple levels of influence, including the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and societal levels.16,17 According to this framework, race/ethnicity, gender and SEP are social categories that reflect societal inequalities and lead to differential distribution of stressors, power, status, and resources.6 For example, race shapes differential exposure to life opportunities and resources in society, resulting in racial and ethnic minorities being disproportionately poor, having lower access to high quality medical care, and less continuity of care.18 The social contextual framework, as applied in this study, is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Application of the social contextual framework.

Methods

Sampling and recruitment

We chose a qualitative study design, using in-depth interviews, to achieve our study aims. A purposeful sampling technique19 was used to obtain sufficient representation of both Black and Latina women who had a mammogram that resulted in need for follow-up. Women from locations with a high volume of lower-income, multi-ethnic patients, including a community health center, a breast evaluation center at a public hospital, and a mammography van, were invited to participate. Eligibility criteria included: 1) having an abnormal mammogram finding within the year prior to study enrollment; 2) being 40 or more years old; 3) fluency in English, Spanish or Haitian-Creole; and 4) being capable of providing informed consent. Women with a history of breast cancer were excluded. Clinic staff presented study information to potential participants and asked permission to provide contact information to research staff. If interested, research staff tried to contact each woman by phone up to ten times to obtain consent and schedule interviews. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and within participating sites. More information about recruitment and sampling is available (see Allen, Shelton, et al., 2008).14

Data collection

Interviews took place between 2002 and 2005 at a time and place convenient to the participant, such as the woman’s home or a community center. Participants were interviewed in their preferred language, usually by an interviewer of the same race/ethnicity. Interviews were audio-taped and professionally transcribed; interviews in languages other than English were professionally forward- and back-translated by a native speaker. A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on existing literature and was broadly informed by the social contextual model. Open-ended questions covered a range of topics, with examples of sample questions provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Constructs addressed in life history interview and sample questions

| Constructs addressed in interviews | Sample questions |

|---|---|

| Life circumstances | “Are you working outside the home? What kind of work do you do.” |

| “ Do you have enough money for basic needs each week?” | |

| “ What kind of contact do you maintain with family?” | |

| Self-care | “What kinds of things do you do to take care of your health?” |

| “Do you think women should spend time and money taking care of their health? Why or why not?” | |

| Attitudes towards cancer, breast cancer, and screening | “What first comes to your mind when you hear the word cancer?” |

| “Do you think there are things that people do or things that happen to them to cause cancer? Please describe.” | |

| “If a woman had breast cancer, do you think she would want people to know about it? Why or why not?” | |

| “Can you tell me about your decision to get a mammogram” | |

| Information about cancer and screening | “Where do you get most of your information about cancer and cancer screening? How much do you trust the information that you get from _____?” |

| “Do you ever talk about cancer or cancer prevention with your friends and relatives?” | |

| “Do you think that your doctors give you enough explanation about the tests that are done to look for cancer? Why or why not?” | |

| Social relationships and orientation towards life | “Who is important to you?” |

| “In what ways do you help family members of have responsibilities to other people?” | |

| “What kinds of things do you worry about?” | |

| Access to care | “Do you feel that you can get health care when you need it? Why or why not?” |

| “Is there anything that makes it difficult to get health care?” |

Analyses

A thematic content analysis approach was used to understand patterns in the data. Research team members (consisting primarily of study Investigators trained in Anthropology and Public Health) reviewed transcripts, identified major themes, and met regularly as a group to discuss interpretations. Through this iterative group process, code definitions were developed and refined, and new themes were identified (see Allen, Shelton et al. for more information).14 Line-by-line coding was conducted using N’Vivo software (QSR International, 2000).20 The social contextual framework served as an organizing approach for reporting results of these analyses and themes that emerged.

Results

Study sample

The final sample was comprised of 64 women. Fifty-three percent of participants were between the ages of 40–49 years old and 56% were employed in part/full-time work. Sixty-three percent of the women were Hispanic and 33% were Black (predominately African American). The majority of women were born outside of the United States (69%) and preferred Spanish as their first language (59%). Only 23% of participants were married or living as married. Many women (43%) had a High School Education or less. In terms of health care access, 22% had private insurance, 13% had no insurance, 27% had the state’s Medicaid coverage, and 35% had Free Care (a program requiring hospitals/health centers in Massachusetts to provide free or reduced cost health care to the uninsured). The full sampling scheme is presented elsewhere.14

Social contextual and psychosocial factors - Individual level

Cancer-related attitudes and beliefs

The overwhelming majority of women had very negative connotations of cancer; many associated it with a ‘death sentence’. There was a great deal of shame and embarrassment associated with cancer, particularly cancer of the breast. For example, most women said that people diagnosed with breast cancer would likely hide their disease due to fear of social rejection or stigmatization, or because they would not want to be pitied or devalued by others in their community. Some feared they would no longer “feel like a woman” due to disfiguration if they lost a breast. They worried how this would impact their relationship with their spouse or partner. According to one Black woman: “I would want to speak about it [breast cancer]. But the majority of my friends and family? No. Because they come from the school of thought that a woman is not a woman if she doesn’t have her uterus and her ovaries or her breast.” Many Latinas also said that they would hide a diagnosis, but this was most often due to a desire to shield family members from the pain of knowing about a loved one with cancer.

Most women attributed cancer to smoking, hereditary factors, and environmental pollutants or chemicals at work and home. A number of women held misperceptions about the causes of cancer, including the belief that cancer is contagious, caused by physical blows (including abuse), or related to ‘bad’ behaviors (e.g. drug use, abortion) or strong emotions (e.g. stress, anger). Misperceptions about the causes of cancer were often rooted in observations of their own lives: “My father smoked but my father did not die of cancer. My aunt smoked but she did not die of cancer either. My mother did not smoke and my mother died very young of cancer.” Many women reported having positive attitudes about mammograms, although about half of the women did not recognize them specifically as ‘cancer screening tests.’ According to one Latina: “I don’t have tests for cancer illnesses. The tests I do are either for mammogram or Pap smear.”

Religious and fatalistic beliefs

For many women, a belief in the will of God co-existed with a willingness to obtain medical care, such as breast screening. Nearly every participant referenced their faith in God, and said they pray for health. A common idea was that God determines both sickness and health. According to a Latina: “God gives the sore and He cures it”. A sense of leaving everything in God’s hands also arose, as reflected in this statement from a Latina about breast cancer: “If that’s what God would give me, I won’t reject what God wants.” A few women did not worry about getting sick because they would be ‘saved’. According to a Black woman: “I’ve been smoking since I was 17…I don’t get sick…I talk to God and ‘by strife, I am healed’.” Nevertheless, they spoke about the need to care for their health, in spite of believing in fate as determined by God.

Health issues

Good health was highly valued and mentioned spontaneously in the majority of interviews. According to a Latina: “I would give anything to not have any more health problems. I don’t care about being poor, but being sick.” Nearly a third of the participants reported physical or mental health issues, including stomach and cervical cancer, lupus, fibroids, arthritis, depression, asthma, high blood pressure and cholesterol, chronic back pain, and diabetes. Several women thought that these health problems were somehow linked to cancer. A Latina said: “Even if they tell me it’s arthritis, for me it’s cancer,” and a Black woman said: “I’m thinking maybe this isn’t sciatica in my back; maybe it’s cancer.” Most women discussed the negative impact these health problems had on their lives. A Black woman with diabetes explained why she had been avoiding the doctor in general:

It’s very depressing to have to go to a doctor once a month…I’m not an old women…I’m older, but when you’re forty-something and you’re going to the doctor once a month, it does get depressing. When you’re doing four needle shots a day, it’s depressing…So a lot of times, I was suffering with depression.

In contrast, although much less common, a handful of women discussed the facilitating role of health problems. For example, one Black woman talked about how her health problems actually enabled her to go back for her follow-up mammogram appointment: “So I had to see my diabetes doctor, and what I did is that I fitted that mammogram in at the same time… So, I can kill two birds with one stone. I think I killed three because I had to see my endocrinologist as well.”

Material and economic hardship

A common and pronounced theme throughout all of the interviews was the stress associated with economic hardship. Most women said that they struggled each week to make ends meet and to cover the costs of basic necessities (e.g. food, rent). Several women explained the measures they took to meet their basic needs, which included collecting cans and bottles in exchange for food, abstaining from eating three meals a day, and going to food pantries. Some women explained that they had put aside their own plans and dreams (e.g.. going to school) to care for their children, which contributed to their inability to have steady work and adequate income. A sense of shame about lack of money permeated the interviews, as did a sense of feeling de-valued generally by the broader society. A Black woman explained: “It’s sad that in this country, if you don’t have money, you really don’t count.” Lack of financial stability also contributed to a sense of hopelessness about the future. In response to a question about her hopes for the future, one woman related “That’s a hard one, because I don’t have no future…my future will be the same as now…I have dreams, but hey…dreams do not come true.”

Economic hardship was largely rooted in un- or under-employment. Just over half of the sample was employed, typically in the service industry, including childcare, cleaning, and food services. Some Latinas noted that they had better jobs in their home countries, but struggled to find comparable work in the U.S. because of documentation issues or language barriers. One woman was an accountant in Colombia, but could only find work ironing clothing in the U.S.: “Here I do what I can, since I don’t know English. I do recognize it’s because I’m ignorant.” Reasons for unemployment varied; some women did not work because they were disabled or caring for family members, while others were frustrated at being unable to find a job. Embarrassment and shame also arose in the context of work and education. A Latina shared: “I want to work, but I’m scared to do it. I want to depend on myself, but sometimes it’s not easy, especially when you’re not finished school,…I’m 43 years old and that’s embarrassing for myself.”

Economic hardship clearly impacted women’s ability to afford housing and pay rent. Out of economic necessity, many women were living with family members; a few Latinas felt ‘trapped’ at home and frustrated by their dependence. An unemployed Latina who lived with one of her children explained: “I don’t have any money. And…although they are my children, I feel bad…. Because I feel that I am a burden.” Of note, nearly every woman in the study said she dreamed of one day owning her own home.

Social contextual factors- Interpersonal level

Social ties and social isolation

Across race and ethnicity, nearly every women in the study reported being emotionally close to their children. Beyond children, however, the nature and extent of social ties varied. In general, Black women reported having many family and friends in their network, both in the Boston area and across the U.S. In comparison, Latinas’ relationships were more limited in the U.S., with most of their close ties within their home countries. Many Latina immigrants expressed feeling socially isolated; some connected this ‘emptiness’ to being separated from family, often because they were awaiting documentation so that they could visit their country of origin and be able to return to the US. According to one: “I only have my husband’s family here, after that I don’t trust anyone here.” Another Latina whose husband had died said “I am alone…and alone I will remain….”

Some commented on how loneliness can lead to other more serious problems. A Latina explained: “Because I think that when you’re alone in another country it’s not easy…. There are difficult times when you feel alone, you feel depressed…so you feel homesick or you don’t want to be here. Many people turn to the streets, drugs or alcohol, prostitution.” Another Latina expressed: “I’m concerned about the loneliness and I’m concerned about getting sick in this country, because I don’t have anyone that supports me…Who is going to give me a hand?”

Abusive/difficult relationships and major life stressors

A large number of women talked about major life traumas in connection with their social relationships: a few women had been married to alcoholics; several were orphaned; one had not seen her husband for many years; one lost many friends to HIV/AIDS; another was caring for 11 children; and many had been widowed and left to care for children alone. These events or relationships were often described as being major sources of stress, as expressed by a Latina woman: “Many, many times, I found myself in a situation, which I said, ‘I want to kill myself’ or ‘I want to die.’…I have been through so much pain, because one suffers so much.”

Some of the women were victims of abuse, with a few still trying to get out of abusive relationships. One Latina explained why she has no future plans: “Honestly, I lived a rough life, I suffered too much, so I’m not thinking about myself now, what kind of future I’m going to have… My father, he was sick, he was alcoholic. He was abusive, to my mother, myself, my other sister, my brother. So, with life, it was not easy, it was a rough time.” A few women talked about abuse by partners and relatives, and some cited psychologically and physically abusive work situations. It is important to note that a strong sense of pride and resilience emerged from some interviews, often in relation to overcoming tremendous challenges such as raising their children on their own. According to a Black woman who had overcome homelessness and drug addiction: “I’m proud of my determination…A lot of people call me the ‘Rock of Gibraltar.’

Demanding Family Roles and Responsibilities

Most of the women in the study had multiple family roles, assuming responsibility for the majority of household tasks for their families, often as single mothers with little support from a partner. According to one Black woman: “I am the backbone of my family…stressful…everyone depends on me to have an answer all the time or to be strong.” In many cases, since multiple generations lived together, many women had caregiving responsibilities that pertained to not only their children, but also their grandchildren and/or parents. For example, a Black woman with five children helped care for her granddaughter, a mother with Alzheimers, and a sister with bone disease. Many women discussed the strain of parental caretaking, in particular.

These caretaking responsibilities often hindered women’s abilities to balance work, family, and household duties. Some acknowledged that this resulted in putting their own needs behind those of their family. When asked whether women should spend time taking care of themselves, most agreed that they should, but often qualified this by saying that they needed to care for themselves, so that they could care for others. One Latina stated: “We should take care of our health so we can be there for our family”. Throughout the interviews, a major theme that emerged was that women’s families, and most commonly their children, were a highly valued and central part of their lives. Many women talked about how the socially-defined role of women as self-sacrificing caretakers was instilled in them by their culture, and passed on to them through family. According to a Black woman: “I think it was tradition. I guess [being] the ancestors of a slave [African-Americans], the women have to do double-duty.”

Cancer-related Experiences among Friends and Family

Most women knew at least one family member or friend who had cancer. For some with a family history of cancer, this led them to worry about their own health. A Black woman who had five family members with cancer relayed her fears: “If I put a blindfold on and stay ignorant, I won’t know and I won’t worry…and it won’t bother me….” Exposure to others who had experienced cancer motivated some to go to their appointments and served as a wake-up call: “We are all more aware, due to what happened to our aunts. We are more on top of getting a mammogram.” Others reported that having a family history of cancer was a deterrent to self-care. A Latina whose family member died of cancer explained: … each time I go to do an exam I get scared…that’s why it’s been difficult to go back and do the exam…. Because when you go through this experience with a family member, it stays on your mind.”

About half of the women said that family and friends were a key source of cancer information, often because they felt they received inadequate information from health care providers. Women who said they don’t talk to family and friends about cancer attributed this to not knowing anyone with cancer, or because it is uncomfortable, scary or ‘taboo’ to discuss.

Social Contextual Factors- Organizational level

Access to Care and Insurance

Insurance-related barriers served as a common theme and a major source of stress for many. As one Latina recounted: “Sometimes we don’t even want to go to the doctor, because Free Care doesn’t cover some things… People are scared to get sick here.” Some women felt a tension between attending to their health and the strain of not knowing what was covered by insurance. A number of women recounted receiving bills for hundreds or thousands of dollars for services or medications, after they had been told that they would be covered. According to one woman: “It’s ridiculous! I mean, I have enough to worry about…I have $3000 worth of bills from it at home. I have to worry about…I only have $5.”

Some women with Free Care noted that their coverage had expired, and that they did not know how to renew it, or were in the process of obtaining approval. Several women said that they could not afford or did not qualify for insurance, despite being employed. A Latina who had to retire due to illness stated: “That’s my biggest concern… I feel…like between two walls because the medicine that cures me and makes me feel better…I can’t take it… because I had the health insurance of my job…” A few of the women also felt that they received lower quality services because they received Free Care.

Notably, some women, particularly Latina immigrants discussed how grateful they were to have access to good health care in the U.S., contrasting it to the services offered in their home countries. Some women felt that the services in the US are more advanced, the providers more trustworthy, and that there are more programs for low-income women in comparison to their home countries. According to one woman whose two aunts died of cancer because they could not afford the exams in her country: “I take advantage of every opportunity that they give me [in the US]…. Because I bring the experience of my country where if you don’t have money you don’t get examined.”

Health Care Providers- The Role of Gender and Language

Many women (particularly Blacks) expressed the importance of having female staff and health care providers for breast-related issues, due to increased trust and comfort. A Black woman explained: “You need a woman. I’m not being a female misogynist here, but in the case of breast cancer, that person that makes contact with people who won’t come back, should not be the male primary care provider” and later continued “but if your primary care [provider] is a male…you only hear the medical, technical stuff.” Another Black woman shared: “I had a male gynecologist…I think I was intimidated by him, and I wouldn’t ask as many questions, or maybe I wouldn’t understand the answers. And if I didn’t understand the answers, I wouldn’t press the issue.” And another black woman said: “I find a woman doctor is more apt to talk about cancer and related issues than a man doctor is…. She’s just more open with it.” A Latina woman agreed: “I’ll trust the female doctor more.”

Having a health care provider who spoke the same language was very important among Latinas. Many Latinas commented on the difficulties they faced in communicating with their providers. Even with interpreters, some stated that they were not fully able to express themselves: “I would want to take my frustration out or explain myself and can’t. It is not the same if someone translates for you.” As a result, some Latinas felt they were neglected or that they received incomplete information about their health.

Employment-related Policies

Some women voiced the importance of staying employed to survive, often putting job security over other needs, including attending medical appointments. This tension arose most often in situations where women worked in settings with unsupportive or inflexible work policies. According to a Latina: “I’m worried because my job is my only income…to survive…If I’m careless about my job they can take it away or something, so I have to do it [miss appointments when they ask her to work].” A Black woman also expressed the tension between health and work: “..without a job and no insurance, no hospital appointments! …I still got to pay my bills and if I don’t have any sick time then I go off the books.”

Social Contextual Factors- Community and Societal Levels

Few themes arose at the community-level. Most women said that they chose their health center because it was conveniently located in their neighborhood, which made accessing care easier, particularly for women who relied on family members for transportation or faced other barriers to transportation. In contrast, a number of themes arose at the societal level, as presented below.

Discrimination and Mistrust

Perceived discrimination emerged as a common theme particularly among Black women. This resulted in feelings of mistrust towards health care providers. A few Black women said they mistrusted the information from providers because ‘health care is a business and it is in doctors’ best interest for people to be sick.’ One woman noted:

Because of what society used to do to us as people, some of the elders are fearful, going to doctors. Based on their skin color. We used to actually have doctors who would… call us problems, as opposed to taking care of our problems, for medical research, because they figured our people weren’t worth the value. So, we learned a lot of in-home medical procedures that was passed down from the elders through different generations, and there are a lot of people who are alive today that… they won’t go see a doctor unless… you’re there with them. You have to walk them through it because they actually fear that they’re going to create something on them…

Other Black women felt that health care providers were not forthcoming with health information or were too busy to address their concerns. One Black woman commented how angry she got about how “unfair things are for us” (being Black and female), and felt providers did not pay attention to her: “They have to take the time…especially amongst women of color”. This may explain why several Black women expressed a preference for having Black doctors. Several women also talked about the importance of having access to educational materials that they could identify with. A Black woman asserted: “They need to have more diversity in the pictures…for women. Because it’s our issues too…. It’s all women…They need to show…you know black doctors.”

A theme also arose in relation to overall mistrust of the health system, and medical research in particular. One Black woman who said she had trouble accessing care because “I have a problem trusting doctors”, also expressed distrust of research: “You know, especially over the history of medicine, they’ve always used minorities in their experiments, in their procedures…and that goes way back now, a stretch.” Another Black woman agreed: “All my life, being Black, being female, someone has always had to die before I could benefit.”

Immigrant Status and Documentation

The interplay between financial challenges, social relationships, and need for health care was complex for Latina immigrants and arose as a common theme. Many commented on how limited finances restricted them from visiting their families in their home countries. Most came to the U.S. for their families, often with great sacrifice, in order to be near their children in the U.S., to earn money to support their families, or to give their children what they called a ‘better life’. One Latina woman said: “I have not been able to have what I wanted, meaning studying, have a career, because I was poor. And I came to this country to persevere, to get ahead, and raise my children. And I told them, ‘What I did not achieve, I want you to get.’” Another explained the stress she felt because she was responsible for providing economic support to her family back home: “My family depends a great deal on me. That is why I came to this country.” A lot of Latinas expressed the difficult transition they experienced coming here. One Latina women said: “It’s not like you are fine here, but because of the love [for your family] you hold on.”

Documentation issues were repeatedly raised by Latinas, particularly in relation to the emotional strain they felt due to being separated from their families. Several women also explained the stress they felt due to working illegally: “Honestly, I worry a lot about finances, it’s that, I’d like to have the opportunity to work legally without thinking I’m breaking the law, I’d like to do that, but no…” A few women said they had feared going to the doctor when they came to this country because they were undocumented.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to explore the social context and psychosocial beliefs of low-income Black and Latina women that may influence their ability to follow health recommendations and behaviors. We found that the social context of these women’s lives was heavily influenced by a number of interconnected major life stressors that hinder health promotion in general, and the ability to follow behavioral recommendations in particular. These included: negative and inaccurate perceptions of cancer; fatalistic beliefs; competing health issues; economic hardship; abusive and difficult relationships; demanding caretaking responsibilities; cancer-related experiences of friends/family; insurance struggles; mistrust of health care providers; and unsupportive employment policies.

The burden of the social context of socially disadvantaged populations has not been adequately described, especially as it relates to health behaviors and adherence, and is particularly poignant when viewed through the eyes of participants. In general, there has been a tendency in public health and medicine to focus on health behaviors and diseases in isolation, without full consideration of the broader social context.11,21 However, as these narratives demonstrate, women’s health is intimately connected to their social and contextual life circumstances. In the context of the major life stressors and competing priorities described by the women in this study, it should not be surprising that many have difficulty making their own health care a priority. These findings are consistent with prior research on gender-defined roles, responsibilities, and expectations that often result in women taking on a disproportionate burden of caretaking and household duties and facing competing work/family demands,22–24 demands that often interfere with women completing behavioral health recommendations.25–27

Some themes that arose were differentially influential by race and ethnicity. Latinas expressed challenges to self-care related to immigration, documentation, difficult transitions to the U.S. (i.e., language barriers), and social isolation. Similar themes have arisen in life history interviews previously conducted among working-class, multi-ethnic populations in the same geographical area.12 Black women more often described experiences of discrimination, often in relation to distrust of health care providers, the health system and medical research, as has been previously documented in the literature.28–30 Other studies have documented that mistrust is rooted in the history of harmful treatment of Blacks, ranging from slave experimentation, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and inequities in health care access and treatment.2,31,32 Researchers may want to investigate how immigration-related difficulties, discrimination and medical mistrust impact adherence to behavioral recommendations, since these factors have only recently begun to be explored.

Limitations of this research should be highlighted. First, we caution against generalizing these findings beyond the population examined here. These findings are not intended to capture all of the life experiences of urban, lower-income Black and Latina women, but are useful in generating hypotheses that can be tested in future research. We were not able to explore differences across the myriad groups that constitute Black and Latina communities, for example by region or country of origin. We recognize the tremendous heterogeneity within these populations, but were limited by sample size. In addition, while a sense of resilience and strength emerged from the interviews, the majority of themes focused on the hardships and challenges that women faced across multiple life domains. While this is reflective of the life circumstances of these women, future research should explore the strengths, assets, resources, and resiliency of underserved populations in more detail.

Despite these limitations, this study offers a number of strengths. We used an in-depth qualitative methodology that is well-suited to achieving our research aims and is effective in establishing trust and rapport with minority women, and collecting their thoughts and opinions in their own words. This large qualitative dataset provided detailed exploration of social contextual factors from the perspective of low-income Black and Latina women themselves. This research provides rich narratives that can help inform future research and conceptual models among similar populations of lower-income women, and can be used to inform quantitative measures that seek to measure aspects of social context. These findings may also be useful in guiding interventions and policies to encourage and support adherence to behavioral recommendations among lower-income, multi-ethnic women.

There are a number of implications that follow from this research. Qualitative data that considers the complex social, contextual, and material context of people’s lives, as was collected here, is particularly useful for informing the design of socially and culturally appropriate policies and interventions.12,33 Given that the themes and health-related barriers arose at multiple levels (i.e. individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and societal levels), it is critical that future interventions and programs take a multi-level approach and address multiple levels for change. In the case of promoting follow-up after an abnormal mammogram, most interventions have provided patient-level education (i.e. through phone counseling, personalized letters).34 Clearly, improved communication and health education is important, particularly among racial/ethnic minority populations who more commonly cite communication difficulties with physicians.35,36 Some of the cancer-related misperceptions and fatalistic beliefs that emerged here highlight the need for providers to understand patients’ health belief systems; improved understanding of these culturally-informed beliefs may help improve patient/provider interactions, and ultimately health behaviors and outcomes.36 Awareness of the social context of low-income women can also help increase physicians’ understanding of the competing demands women face - demands that may take priority over health-related needs out of necessity.

While individual-level interventions are important and may be particularly useful for educating patients about cancer prevention, systems- and policy-level interventions hold greater promise for long-term, sustainable change.11 This is especially the case for disadvantaged populations who have received less benefit to date from individual behavior-change interventions and suggests the need for novel and more contextually-based approaches that recognize the complexity of people’s lives.11 Health care provider- and systems-level interventions might include phone notification of results or reminders, centralized services, and patient navigators.37 Patient navigator and lay health advisor programs are a particularly promising avenue, given that they can help address some of the challenges that low-income women face. For example, navigators provide centralized care and have been found to decrease barriers and anxiety, improve trust and communication, and improve behavioral adherence.38–41 To facilitate trust, women in our study also identified the importance of having female health care providers of the same race/ethnicity and providers who spoke their language, aspects of programs and programs that also hold great promise.

Given the stressful social contexts that we have documented here, delivery of health services must address the multiple challenges low-income populations face, and it is imperative that health care services must be made as accessible, convenient, affordable, comprehensive, and integrated as possible. Those in this study, who experienced multiple health issues and had to juggle multiple responsibilities and roles, faced sometimes insurmountable barriers to access of care. In a context where health services have become increasingly specialized and disaggregated, these women would greatly benefit from health services that are integrated across disease entities, and that offer both physical and mental health services in one location. Health systems could also be improved by policy changes, including having more flexible hours at health centers/clinics. Increasing the availability of services at the local and neighborhood levels may help improve accessibility of services, as might transportation vouchers or free shuttles.

As health disparities are embedded in larger social, political, and economic contexts, elimination of inequities will require interventions that do more than address health care policies. Effective policies and efforts to eliminate health disparities must also address social inequities and fundamental non-medical determinants of health as well.42–44 Specifically, social polices can help improve the living and working conditions of low-income populations, since our social environment structures our opportunities and chances for being healthy. For example, low-income women are more likely to be part-time employees or unemployed, and therefore inadequately insured; policies must be put in place to provide universal health care coverage to ensure that everyone is adequately covered. Steps to diminish financial barriers to health care have been instituted in Massachusetts though Massachusetts Health Reform, although only time will tell the impact of this legislation. For women who are working, employers can offer flexible work policies to facilitate attendance at medical appointments, though this recommendation may be met with strong reluctance from employers in the service sector where much of this population works. Social policies can also help increase funding to improve the living conditions of lower-income women, devoting money and time towards improving the quality of housing, education, employment opportunities, income support, neighborhood conditions (e.g. safety), and access to resources and facilities (i.e. transportation services, clinics, parks, affordable and healthy supermarkets, job training) in low-income neighborhoods (see Williams et al., 2008) 44 for a review of interventions and policies that have been used to address social determinants of health).

With ethnic and racial diversity growing rapidly within the U.S., eliminating health disparities is imperative and will require a better understanding of the social context in which health behaviors are developed and maintained. This research illuminated numerous life circumstances and social contextual factors -- linked to the status of low-income minority women -- that have important health consequences. Future research is needed to test some of the hypotheses formulated here. Specifically, a greater understanding of the pathways by which these circumstances and stressors interact and impact health behaviors and outcomes is needed in order to develop effective comprehensive multi-level interventions, and to identify resources, supports, services and policies that may help mitigate the potentially negative consequences of these social contextual influences on health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from Susan G. Komen for the Cure. The authors are grateful to María Inés Castro, Bruce Chabner, Atala Esquilin, Dora Gutierrez, Elizabeth Harden, Kristen Mason, Liz Matos, Mary Neagle, Joni Shaw, Wanda Turner, Karen Ruderman, Michelle Wilson, and to the wonderful women who participated in the study. Funding support for the lead author (R.S.) was also provided through the National Cancer Institute by the Harvard Education Program in Cancer Prevention Control (5 R25-CA057711-14) and the Mount Sinai Program in Cancer Prevention and Control: Multidisciplinary Training (5R25-CA081137).

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Health. 2. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. The Unequal Burden of Cancer. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooks RN, Simonsick EM, Klesges LM, et al. Racial disparities in health care access and cardiovascular disease indicators in Black and White older adults in the Health ABC Study. J Aging Health. 2008;20(6):599–614. doi: 10.1177/0898264308321023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, et al. Model for incorporating social context in health behavior interventions: applications for cancer prevention for working-class, multiethnic populations. Prev Med. 2003;37(3):188–197. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enn C, Goldman J, Cook A. Trends in Food and nutrient intakes by adults: NFCS 1977–1978. CSFII 1989–1991, and CDFII 1994–1995. Fam Econ Nutr Rev. 1997;10:2–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE, et al. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relationship to physical activity during leisure time: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmons KM. Health behaviors in social context. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 242–266. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman R, Hunt MK, Allen JD, et al. The Life history interview method: Applications to intervention development. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(5):550–581. doi: 10.1177/1090198103254393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angus J, Miller KL, Pulfer T, et al. Studying delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment: critical realism as a new foundation for inquiry. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(4):E62–70. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.E62-E70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen JD, Shelton RC, Harden E, et al. Follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms among low-income ethnically diverse women: Findings from a qualitative study. Patient Educ Counsel. 2008;72:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice PL, Ezzy D. Qualitative research methods: a health focus. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLeroy K, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 3. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DR. Racial/Ethnic variations in women’s health: The social embeddedness of health. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):588–597. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabtree F, Miller WI, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis program, version 1.3. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKinlay JB. The promotion of health through planned sociopolitical change: challenges for research and policy. Social Sci Med. 1993;36(2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90202-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coltrane S. Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62:1208–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeVault ML. Feeding the family: The social organization of caring as gendered work. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devine CM, Connor MM, Sobal J, et al. Sandwiching it in: spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Social Sci Med. 2003;56:617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgess C, Hunter MS, Ramirez AJ. A qualitative study of delay among women reporting symptoms of breast cancer. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(473):967–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler BA. Social processes used by African American women in making decisions about mammography screening. J Nurs Scholarship. 2006;38(3):247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messina CR, Lane DF, Glanz K, et al. Relationship of social support and social burden to repeated breast cancer screening in the women’s health initiative. Health Psychol. 2004;23(6):582–594. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, et al. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;2–3(118):358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(suppl 1):146–161. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gamble VN. A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9(Suppl 6):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92(12):563–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krumeich A, Weijts W, Reddy P, et al. The benefits of anthropological approaches for health promotion research and practice. Health Educ Res. 2001;16:121–130. doi: 10.1093/her/16.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bastani R, Yabroff KR, Myers RE, et al. Interventions to improve follow-up of abnormal findings in cancer screening. Cancer Supp. 2004;101(5):1188–1199. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:146–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282:583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackman DJ, Masi CM. Racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality: Are we doing enough to address the root causes? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2170–2178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, et al. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population: A Patient navigation intervention. Cancer Supp. 2006;109(2):359–367. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: Current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104(4):848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, et al. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: A randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Urban Health. 2007;85(1):114–124. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.House JS, Williams DR. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. Understanding and Reducing Socioeconomic and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health; pp. 81–124. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, et al. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors and mortality: Results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1703–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, et al. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve and health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Management Practice. 2008 Nov;(Suppl):S8–S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]