Abstract

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecological malignancies in women. The primary challenge is the detection of the cancer at an early stage, since this drastically increases the survival rate. In this study we investigated the dielectrophoretic responses of progressive stages of mouse ovarian surface epithelial (MOSE) cells, as well as mouse fibroblast and macrophage cell lines, utilizing contactless dielectrophoresis (cDEP). cDEP is a relatively new cell manipulation technique that has addressed some of the challenges of conventional dielectrophoretic methods. To evaluate our microfluidic device performance, we computationally studied the effects of altering various geometrical parameters, such as the size and arrangement of insulating structures, on dielectrophoretic and drag forces. We found that the trapping voltage of MOSE cells increases as the cells progress from a non-tumorigenic, benign cell to a tumorigenic, malignant phenotype. Additionally, all MOSE cells display unique behavior compared to fibroblasts and macrophages, representing normal and inflammatory cells found in the peritoneal fluid. Based on these findings, we predict that cDEP can be utilized for isolation of ovarian cancer cells from peritoneal fluid as an early cancer detection tool.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecological malignancies and the fourth leading cause of death in women in the United States among all cancers.1, 2 The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 225,500 women worldwide are diagnosed with ovarian cancer3 and 140,200 women die from it annually. In the U.S., it was estimated that 21,990 new cases of ovarian cancer would be diagnosed in 2011 and 15,460 women would die from this disease.4 Much of this lethality is attributable to its late detection due to the lack of symptoms of earlier stages, and routine screening methods are not established. However, early detection improves the survival rates of women to more than 90%,5 highlighting the importance of early detection and treatment of ovarian cancer. Ideally, screening tests should be non-invasive and highly specific to reduce false-positive results, the associated risks, and costs for the affected women.2

Ovarian cancer cells exfoliate from the primary tumor and disseminate throughout the peritoneal cavity. The changing peritoneal microenvironment, characterized by increasing numbers of immune cells, mostly monocytes/macrophages,6 and increased protein and bioactive lipid levels in the ascites fluid7, 8 promotes tumor cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis. Ascites fluid can also contain benign cell populations of macrophages and fibroblasts.6, 9 The percentage of tumor cells versus non-tumor cells can vary greatly in women from 1 to >60%.10 Because of the different physical characteristics of these cells, we theorize that resident and recruited peritoneal cells can be separated from ovarian cancer cells. Unlike cancers of other sites, ovarian cancer cells rarely enter systemic distribution. Thus, the peritoneal fluid is the appropriate source for detection of disseminating ovarian cancer cells.

Traditionally, specific biomarkers expressed mainly by the target tumor cell population are used to isolate cells from each other. CA-125, the most popular biochemical marker for ovarian cancer, is found in 50% of early stage patients and 80% of late stage patients.11 Other markers can vary greatly. Detection techniques include ultrasound and color-flow Doppler imaging, using morphological and vascular markers, respectively.11 Recently, proteomics has become a promising means by which new potential biomarkers are identified. Several of these biomarkers have to be used in combination to improve sensitivity, but at the cost of reduced specificity.11, 12

Roberts et al. have established a mouse cell model for progressive ovarian cancer from C57BL/6 mice.13 Isolated primary mouse ovarian surface epithelial (MOSE) cells undergo progressive changes during culturing.13, 14 Based on their phenotype (size, growth rate, morphology) and their tumorigenic potential, MOSE cells were categorized into early, early-intermediate, intermediate, and late aggressive stages. During neoplastic progression, increased dysregulation of the cytoskeleton organization was observed, which14 was recently found to be associated with stage specific changes in their biomechanical properties.15 The MOSE model exemplifies an alternative to human cell lines since comparable human cell lines providing different stages of ovarian cancer derived from the same woman are not available.

It has been reported that malignant cells are distinguishable from normal and healthy cells based on differences in their electrical properties.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 For example, breast tumors have different electrical impedance compared to their surrounding tissues,21 and transformed cells have higher effective cell membrane capacitance than normal cells.17, 18, 19, 20, 22 Leukemia and breast cancer cells lines have higher effective membrane capacitance than normal T lymphocytes and erythrocytes.17, 18 Also, transformed rat kidney cells,20 murine erythroleukemia cells,19 and oral cancer cells22 have higher effective membrane capacitance than non-transformed counterparts. However, it is not known if this also applies to a progressive cancer cell model derived from syngeneic non-transformed cells. Studying the electrical properties of these cells, thereby eliminating potential inter-individual differences that are inherent to human cell lines, may lead to novel cancer detection techniques. The first step towards this goal is investigating the dielectrophoretic response of cancer cells derived from a non-transformed, spontaneously immortalized mouse ovarian epithelium to determine the changes in their electrical properties during progression.

Dielectrophoresis (DEP), a non-destructive electrokinetic transport mechanism, is a technique employed to manipulate cells in microdevices. DEP has been a very successful technique for the manipulation,23 separation,24 and detection25 of bioparticles. In contrast to techniques such as fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS),26 chemically functionalized pillar-based microchips,27 and magnetic bead cell separation,28 DEP does not require the use of target specific antibodies. Traditionally, DEP utilizes arrays of electrodes to produce non-uniform electric fields to polarize particles and thereby induce movement. However, there are some challenges with bubble formation due to electrolysis, electrode fouling and delamination, and sample contamination.29, 30 In addition, the electric field deteriorates exponentially as distance from the electrode surface increases.31

Modified DEP techniques, such as insulator-based dielectrophoresis (iDEP), have been developed to overcome challenges of conventional DEP. In iDEP, insulating structures are straddled between two electrodes to cause regions of high and low electric field intensity, resulting in non-uniformity of the electric field.29 Such systems were proposed by Cummings and Singh29 and have been applied successfully for manipulation of DNA,30 separation of live and dead cells,32, 33 and separation of different species of cells.34

Contactless dielectrophoresis (cDEP) is a new technique for manipulating cells which eliminates direct contact between the sample and electrodes. In cDEP, an electric field is generated in the sample channel by using two fluid electrode channels which are filled with a conductive fluid. These electrode channels are separated from the main channel by thin insulating barriers. The absence of metal electrodes minimizes sample contamination35 and bubble formation, and resolves issues associated with joule heating.36, 37 We have shown previously that the viability of prostate cancer cells did not change through characterization or isolation by cDEP.38 cDEP has been used to isolate tumor initiating cells (TICs) from non-initiating cells38 and to separate living cancer cells from dead cells37 and from red blood cells.39 It has also been shown recently with cDEP that breast cancer cells from different cell lines exhibit unique dielectrophoretic responses and highly metastatic cell lines can be isolated from less metastatic lines.40

In this work, we examined the changes in dielectrophoretic response of MOSE cells as they progress from benign to aggressive stages of ovarian cancer. Previously, MOSE cells were characterized as stiffer and more viscous when they are benign,15 confirming reports in other cells.41, 42, 43, 44 This suggests that changes in gene expression during progression of ovarian cancer correspond to an altered morphology, decreased cell size, and altered cellular architecture,14 which together not only affect the biological behavior of the cells, but also modulates their biomechanical and, perhaps, their bioelectrical properties.

To our knowledge, there is no information about changes in the electrical properties of ovarian cancer cells as the disease progresses. In this study we demonstrate for the first time that different stages of cancer, progressed from the same progenitor cells, have different dielectrophoretic responses. We also compare the signal parameters (voltage and frequency) required to selectively capture and isolate MOSE cells at different cancer stages from normal fibroblast and macrophages that can be found in the peritoneal fluid. These results demonstrate the potential of cDEP as a method of early detection and diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

THEORY

The DEP force acting on a spherical particle in a non-uniform electric field is given by45

| (1) |

| (2) |

where and are the complex permittivity of the particle and suspending medium, respectively, r is the radius of the particle, σ is the real conductivity, and is the root mean square electric field. , and ω is the radial frequency of the applied voltage.

The Clausius-Mossotti factor, , is a complex function with a real value between −0.5 and 1, and is dependent on the bioelectric properties of the cell. Depending on the sign of the DEP force can either be positive, in which case it is directed towards high electric field gradient regions, or negative, in which case it is directed towards low electric field gradient regions.

Frequencies at which the DEP force is zero are called the crossover frequency, . These are the frequencies at which the real part of K changes sign, . The first crossover frequency of mammalian cells happens between 10–100 kHz, and the second crossover frequency is typically on the order of 10 MHz for a sample with conductivity of 100 μS/cm.46 Cell size, shape, cytoskeleton, and membrane morphology affect the first crossover frequency; and cytoplasm conductivity, nucleus-cytoplasm volume ratio, and endoplasmic reticulum affect the second crossover frequency.47

The material properties of cells and biological tissues change with the applied frequency. This disparity in properties is known as dispersion. At frequencies less than 10 kHz, counterion polarization happens along the cell membrane (α dispersion). In the MHz frequency range, interfacial polarization of the cell membrane occurs, which can develop because of the polarization of proteins and other macromolecules (β dispersion).48 The applied frequencies in our experiments are in the range of 200–600 kHz, which is in between α and β dispersion regimes. Thus, both the counterion polarization along cell membrane (α dispersion) and interfacial polarization of cell membrane (β dispersion) should both be considered as potential reasons for observing differing DEP signature between cells.

As particles move under the influence of the DEP force, they interact with the surrounding fluid and experience hydrodynamic drag

| (3) |

where r is the particle radius and and are the velocities of the particle and the medium, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Device layout

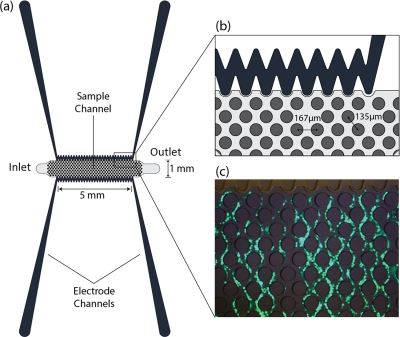

Figure 1 shows the top view schematic of the microdevice. Electrode channels, which are approximately 1 cm long, are separated from the sample channel by 20 μm barriers. Insulating pillars, 100 μm in diameter, in the sample channel increase the non-uniformity of the electric field and enhance the DEP force.

Figure 1.

(a) 2D top view schematic of the microdevices. (b) A section of the microdevice and pillars. Each pillar is 100 μm in diameter. (c) Complete trapping of cells. Calcein AM, enzymatically converted to green fluorescent calcein, is added to the cell sample at 2 μL per mL of cell suspension.

Fabrication process

Experimental devices were fabricated using standard soft lithography techniques. Photoresist, AZ 9260 (AZ Electronic Materials, Somerville, NJ, USA), was spun onto a clean silicon substrate. Then, the silicon wafer was exposed to UV light for 60 s through a mask patterned with the design. Using AZ 400 K (AZ Electronic Materials, Somerville, NJ, USA) developer, the exposed photoresist was removed. The silicon master stamp was etched to a depth of 50 microns with deep reactive ion etching (DRIE). Wet etching with tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) 25% at 70 °C was used for 5 minutes to smooth the surface of the wafer. Then, a thin layer of Teflon was deposited on the silicon master to ease the replication process using typical DRIE parameters.

The liquid PDMS was made by mixing PDMS monomers and a curing agent in a 10:1 ratio (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA). Bubbles were removed from liquid PDMS by exposing the mixture to vacuum for 1 h. PDMS liquid was poured onto the silicon master, cured for 45 minutes at 100 °C, and then peeled off from the silicon mold. Fluidic connections to the channels were punched with a 1.5 mm puncher (Harris Uni-Core, Redding, CA, USA). After treating with air plasma for 2 minutes, the PDMS replica was bonded to clean glass slides using air plasma (Harrick Plasma, Ithaca, NY, USA).

Experimental set-up

Prior to experimentation, the microfluidic devices were placed in a vacuum jar for 20 minutes to reduce issues with bubble formation within the channels. The fluid electrode channels were filled with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Externally, pipette tips formed fluid reserviors at the inlet and outlet of each fluid electrode channel. Metal electrodes were inserted into these reserviors as a means of electrical connection. The main channel was then primed with the sample and a microsyringe pump (Harvard Apparatus Syringe Pumps, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) was used to achieve a flow rate of 0.02 mL/h. Once the required flow rate was maintained for 2 minutes, an AC voltage was applied to the electrodes.

A combination of waveform generation and amplification equipment was used to create AC electric fields in the microfluidic devices. Waveforms were produced with a function generator (GFG-3015, GW Instek, Taipei, Taiwan), and the output was fed to a wideband power amplifier (AL-50HF-A, Amp-Line Corp., Oakland Gardens, NY, USA). A high-voltage transformer was used to step-up the voltage of the signal before it was applied across the fluid electrodes via external electrodes. An inverted light microscope (Leica DMI 6000B, Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL, USA) equipped with a color camera (Leica DFC420) was used to monitor the particles flowing through the main channel.

The dielectrophoretic responses of early (MOSE-E), early-intermediate (MOSE-E/I), intermediate (MOSE-I), and late stage ovarian cells (MOSE-L), as well as macrophages (PC1) and fibroblasts (OP9), were studied separately using the device shown in Fig. 1. The frequency of the AC signal was set as indicated in each experiment for five selected frequencies: 200, 300, 400, 500, and 600 kHz. These frequencies were selected at random, and the associated voltages required to observe trapping of the first two cells (onset of trapping) and trapping of all cells (complete trapping) were recorded (Figs. 1b–1c). Each experiment was repeated 10 times using cells from biological replicates. The student t-test method was used to determine if data from different cell lines were statistically different. The purpose of these experiments was to investigate if there is a difference in onset of and complete trapping between these cell types.

Cell preparation

Different stages of MOSE cells, early (passage number 15–16), early-intermediate (passage number 33–34), intermediate (passage number 70–71), and late (passage number 188–189), were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM)-high glucose medium supplemented with 4% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biological, Atlanta, GA) and 100 μg/ml each of penicillin and streptomycin, at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere as described previously.13, 14

PC1 macrophages were grown in DMEM–low glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO), containing 5 mL of penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 10% FBS (Atlanta Biological). OP9 fibroblast were maintained in α-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), containing 5 mL of penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), and 20% FBS (Atlanta Biological).

The MOSE cells, fibroblasts (OP9), and macrophages (PC1) were grown separately, harvested, washed twice, and resuspended in a low conductivity buffer for the experiments (8.5% sucrose [wt./vol.], 0.3% glucose [wt./vol.], and 0.725% [vol./vol.] RPMI)49 to 1 × 106 cells per mL. The electrical conductivity of all samples was 105 ± 3 μS/cm as measured with a conductivity meter (Horiba B-173 Twin Conductivity/Salinity Pocket Testers, Cole-Parmer) prior to each experiment.

Computational modeling

COMSOL Multiphysics 4.2 (Comsol Inc., Burlington, MA, USA) was used to investigate the effect of different geometrical parameters, such as pillar arrangements, the gap between the pillars, and pillar diameter on and fluid flow.

The electrical properties of PDMS were reported as 0.83 × 10−12 S/m and .27 The electrical conductivities of PBS and DEP buffer were defined as and respectively. Their relative permittivities were defined as , as assumed based on their water content. The properties of PBS and DEP buffer were prescribed for the electrode and sample channels, respectively. The boundary conditions were prescribed as uniform potentials at the inlet and outlet of the electrode channels and insulating on the outside surrounding boundaries.

The fluid dynamics within the sample channel were also modeled to find the velocity field and the shear rate. No slip boundary conditions were applied to the walls of the channel and the pillars. Based on past experiments, the inlet velocity was set to 110 μm/s, approximately corresponding to 0.02 mL/h.38 The outlet was set to no viscous stress (the Dirichlet condition for pressure), and the Navier-Stokes equation was solved for an incompressible laminar flow. The viscosity and density of water, 0.001 Pa.s and 1000 kg/m3, respectively, were used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Computational results

The insulating structures inside the main channel are essential tools to enhance the dielectrophoretic force by increasing the electrical resistance of the sample channel, as well as increasing the non-uniformity of the electric field. Without these structures, gradients in the electric field would be limited to areas close to the side walls of the sample channel, and most cells would not experience a strong enough dielectrophoretic force to be trapped. Adding the insulating structures allows for wider channels with uniform , which consequently increases the throughput and selectivity of the devices.

To compare microdevices with different circular pillar geometries, a diagonal line located on the center of the device has been drawn (line A-B on Fig. 2a). Only the values on A-B′ are shown in Figs. 2b–2d because these values are repeated periodically on other parts of line A-B. Figure 2a shows the contour plot of . For the designs presented here, frequencies from 100–600 kHz and voltages from 0–300 VRMS where studied.

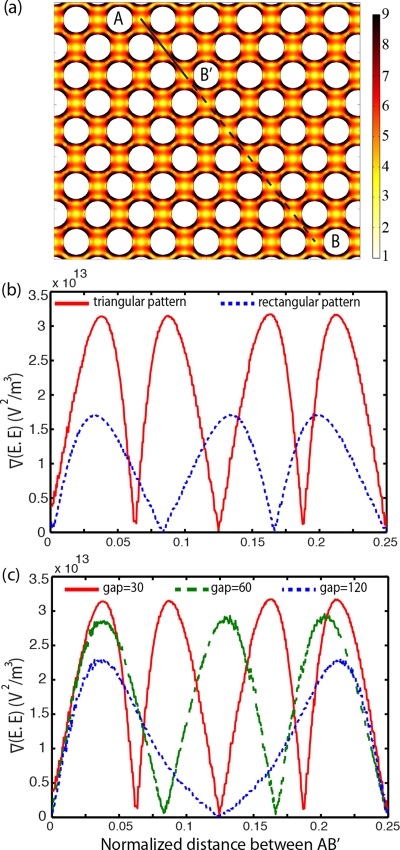

Figure 2.

(a) The gradient of the electric field squared (V2 m−3) at 300 Vrms and 600 kHz. The line plot of on a normalized diagonal line A-B is presented for (b) triangular and rectangular pillar arrangements, (c) circular pillars with 30, 60, and 120 μm gap and diameter of 100 μm, at 100 Vrms and 500 kHz.

Line plots of inside the sample channel for two different pillar arrangements, triangular (staggered, similar to Fig. 2a), and rectangular arrangements are shown in Fig. 2b. These demonstrate that the triangular arrangement creates higher compared to the rectangular arrangement. This arrangement has the added benefit that the calculated hydrodynamic efficiency for capturing cells is better in triangular than in rectangular arrangements.27 Additionally, the triangular arrangement increases the probability of cell trapping since there is a higher frequency of cell collisions with the pillars. Based on these results, a triangular arrangement was selected.

Figure 2c shows the line plot of for three devices with 100 μm diameter and different gaps between the circular pillars: 30 , 60, and 120 μm. This shows that has an inverse relation with the distance between the pillars, i.e., the DEP force increases by decreasing the gap between the pillars, although this increase is not significant. To avoid mechanically filtering the cells, the distance between pillars was not reduced to less than 30 μm. A spacing of 30 μm was used for the remainder of this study because decreasing the gap between pillars increases the number of pillars per unit area, which increases the probability of cell trapping.

Computational results predict that the maximum shear rate in the device has a maximum value of 52 s−1 which is two orders of magnitude less than the cell lysis limit of approximately 5000 s−1.50, 51 In order to trap a cell in a moving fluid, the dielectrophoretic force should overcome the drag force. Figure 3 presents drag force to dielectrophoretic force ratios for pillars with diameter of 50, 100, and 200 μm. It was found that 50 μm pillars have 2.25 times smaller DEP dominant area than devices with 200 μm pillars.

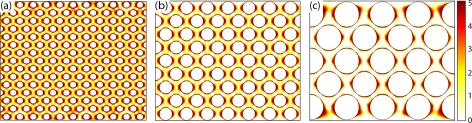

Figure 3.

Ratio of drag force to dielectrophoretic force for microdevices with equal channel width and circular pillars with diameter of (a) 50 μm, (b) 100 μm, and (c) 200 μm. In dark areas DEP force is dominant, and in light areas drag force prevails.

In contrast, increasing the size of pillars reduces the total number of pillars per unit area, which decreases the probability of a cell entering a DEP dominant area. As a compromise between these two results, a diameter of 100 μm was chosen. It is also important to note that the size of the trapping area should be sufficiently large to encompass several particles and avoid saturation; otherwise, the captured cells may be released by small fluctuations in the fluid flow and thus decrease the trapping efficiency.

Experimental results

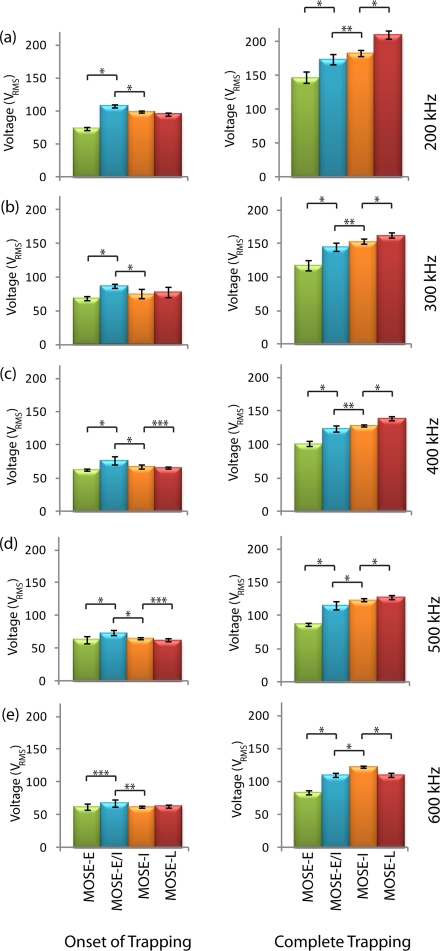

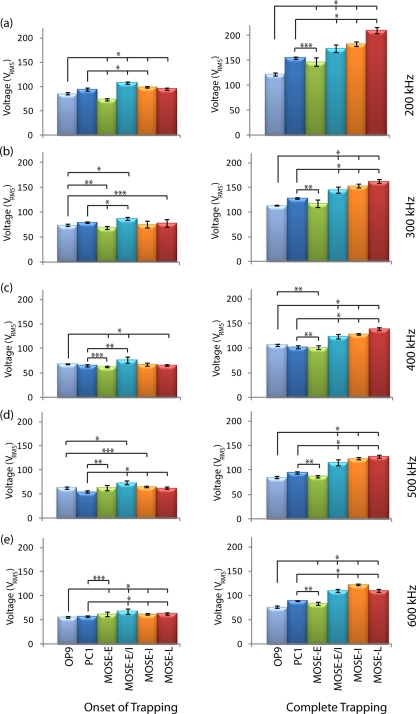

To determine the individual voltages for trapping the MOSE cells, we used the device shown in Fig. 1. Figure 4 shows the onset and complete trapping voltages for four different stages of MOSE cells. The voltages required to trap different stages were statistically different among most stages. The largest variation in trapping between cell types was seen when comparing the voltage required for complete trapping. Between 200 and 500 kHz, the voltage required for complete trapping of MOSE cells increased as the cell type became more tumorigenic. For all cell types, the complete trapping voltages were significantly different with p-values of 0.005 or less.

Figure 4.

Onset and complete trapping voltages of early (MOSE-E), early-intermediate (MOSE-E/I), intermediate (MOSE-I), and late (MOSE-L) cells at (a) 200 kHz, (b) 300 kHz, (c) 400 kHz, (d) 500 kHz, and (e) 600 kHz. Left and right columns present the onset of trapping and complete trapping, respectively. *, **, and *** indicate that data are significantly different with p < 0.0005, p < 0.005, and p < 0.05, respectively, (n = 10).

At 500 kHz, MOSE-L cells were trapped at a higher voltage than MOSE-I cells, while at 600 kHz the reverse occurred. This result did not occur for complete trapping at any other frequencies or for the other cell types, and we predict that the Clausius-Mossotti factor values for MOSE-L and MOSE-I cells intersected at a frequency between 500 and 600 kHz.

The onset and complete trapping of macrophages (PC1) and fibroblasts (OP9) are compared with different stages of MOSE cells in Fig. 5. Voltages for complete trapping of PC1 and OP9 cells are statistically different from the various stages of MOSE cells at almost all applied frequencies in the range of 200–600 kHz. Similarly to Fig. 4, the voltages for onset of trapping are statistically different.

Figure 5.

Onset and complete trapping voltages of different stages of MOSE cells compared with macrophages (PC1) and fibroblasts (OP9) cells at (a) 200 kHz, (b) 300 kHz, (c) 400 kHz, (d) 500 kHz, and (e) 600 kHz. Left and right columns present the onset of trapping and complete trapping, respectively. *, **, and *** indicate that data are significantly different with p < 0.0005, p < 0.005, and p < 0.05, respectively, (n = 10).

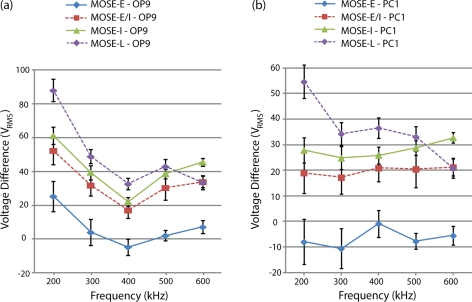

Figures 6a, 6b present the difference between the complete trapping voltage of fibroblasts (OP9) and macrophages (PC1), respectively, with different stages of MOSE cells as a function of applied frequency. These results show that the difference between the complete trapping voltage of PC1 and OP9 and different stages of MOSE cells increases with increases in malignancy and stage of the MOSE cells.

Figure 6.

(a) Difference between complete trapping voltage of (a) fibroblasts (OP9) and (b) macrophages (PC1) and different stages of MOSE cells as a function of applied frequency (n = 10).

Radius and viability of cells were measured using Cell Viability Analyzer (Vi-Cell, Beckman Coulter). The average radius of MOSE-E, -E/I, -I, and -L cells were 7.185 ± 1.004, 7.163 ± 1.245, 7.292 ± 1.493, and 7.050 ± 1.195 μm, respectively. The radii of PC1 macrophages and OP9 fibroblasts were 6.451 ± 1.530 and 6.673 ± 1.211 μm, respectively.

Discussion

The dielectrophoretic properties of cells are influenced by cell membrane morphologies, membrane surface permeability, cytoplasm conductivity, and cell size.52, 53 In this study, the cell size did not dominate the response because the radii of different stages of MOSE cells were in a similar range. Thus, we believe that the observed differences in the DEP response of different stages of MOSE cells (Fig. 4) are due to the intrinsic difference between the cells and not their size, as will be discussed below.

The complex dielectric properties of living cells may result from the expression levels of various surface proteins and interfacial polarization of ions at cell membrane surfaces.54 Since different cells have dissimilar properties, they can be selectively manipulated using DEP. Cell size, shape, and membrane morphology affect the first crossover frequency, and cytoplasm conductivity and nucleus-cytoplasm volume ratio affect the second crossover frequency.31 The first crossover frequency of mammalian cells is typically less than 100 kHz (Ref. 46), and the second crossover frequency is normally in the order of 10 MHz for the sample with conductivity of 100 μS/cm.46 The frequency range used in this study was limited between 200 and 600 kHz; thus, all of the aforementioned biophysical properties, especially membrane morphology, could play a role as to why different stages of MOSE cells exhibit different DEP properties.

The electrical capacitance of the cell membrane is a function of structural features, such as membrane folding, microvilli, and blebs.47 It has been reported that there are more protrusions on the surface of transformed cells than normal cells, which results in transformed cells having a higher effective membrane capacitance than normal cells.17, 18, 19, 20 For instance, leukemia and breast cancer cells lines have higher effective membrane capacitance than normal T lymphocytes and erythrocytes.17, 18 This was also reported for rat kidney cells,20 murine erythroleukemia cells,19 and oral cancer cells.22

It has been reported that there is an increase in membrane ruffles in MOSE cells as they progress to a more aggressive phenotype.14 MOSE-E cells show a more typical cobblestone-like phenotype. MOSE-E/I cells change to more spindle-shape morphology and are smaller than MOSE-E cells. In general, MOSE cells become more spindle-shape and smaller as they progress into MOSE-I and then MOSE-L.14 Among other functional categories, the cytoskeleton and its regulators are significantly altered during MOSE progression, which affects both cell morphology14 and viscoelasticity.15 Based on the presented results (Figs. 4–6), we hypothesize that these morphological changes, including the increase in surface ruffling in later stages, could be the main reasons of dielectrophoretic changes between different stages of cancer cells. This will be investigated in more detail.

In addition, membrane proteins can be related to cells’ dielectrophoretic properties. For instance the dielectrophoretic properties of erythrocytes from different blood types are determined by the diverse ABO-Rh antigens on the red blood cell membrane surface; thus blood cell membranes from donors with different blood types polarize differently.4 In yeast cells, DEP properties are modulated by the binding of lectin which can change the permittivity of the cell.55 These observed differences in DEP response could be due to the expression levels of different, perhaps specific surface proteins or to a change in the total electrical charge and the conductivity of the cell membrane. Clearly, more in depth investigations are needed to identify changes in the MOSE cell membranes that are causal for the changes in their dielectrophoretic properties.

Most studies compare non-transformed cells with highly aggressive cancer cells, often derived from different patients.17, 18, 22, 56 In two other studies, a normal and a malignant cell, derived from the same cell line, have been compared.19, 20 The MOSE model allows for detection of step-wise changes during progression of syngeneic cancer cells, avoiding inter-individual differences that may affect the membrane organization, and thereby influence the dielectrophoretic properties. Thus, this model is more applicable to identify differences between progressive stages of transformed cells derived from the same cell line as would occur in the clinical setting. The current study is the first study that compares the dielectrophoretic responses of different stages of cancer cells, which are extracted from one cell line.

Furthermore, MOSE cells display unique behavior compared to fibroblasts and macrophages, representing normal and inflammatory cells found in the peritoneal fluid. These varying physical properties between MOSE cells, OP9 fibroblasts, and PC1 macrophages can be used to explain the distinct trapping regions among these cells, as shown in Fig. 5. From these data, it would seem possible to selectively screen for ovarian cells in the midst of background peritoneal cells, which is a likely scenario in true patient samples. Thus, these preliminary results suggest that cDEP technique has the potential to be used as a tool for early detection of ovarian cancer.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study is the first study that compares the dielectrophoretic response of different stages of ovarian cancer cells which are derived from one precursor cell line. The results presented here demonstrate that aggressive ovarian cancer cells display a significantly different voltage that allows them to be dielectrophoretically distinguished and trapped from their non-transformed progenitor cells as well as from other cell types that may be found in peritoneal serous exudate fluid. Studying the dielectrophoretic responses of these cells is the first step in developing a clinical diagnostics system centered on contactless dielectrophoresis to separate ovarian epithelial cells from peritoneal fluid to potentially detect even early and intermediate stages of the disease. Early diagnosis will result in early treatment and may increase the survival rates of the affected women. Future work will focus on optimizing device performance and building towards a clinically applicable method for early detection of ovarian cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material is based upon work supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. EFRI 0938047, by the Virginia Tech Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science (ICTAS), by the Diversity Summer Research Program (DSRP), and by NIH RO1 CA118846 (to EMS and PCR). The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark A. Stremler, Bioelectromechanical Systems (BEMS) laboratory members, Hadi Shafiee, Roberto Gallo, Elizabeth Savage, and Andrea Rojas, and Dr. Schmelz laboratory members, Amanda Shea and Chun Cao, for their contributions.

References

- Visintin I., Feng Z., Longton G., Ward D. C., Alvero A. B., Lai Y., Tenthorey J., Leiser A., Flores-Saaib R., Yu H., Azori M., Rutherford T., Schwartz P. E., and Mor G., Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1065–1072 (2008). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs I. J. and Menon U., Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 355–366 (2004). 10.1074/mcp.R400006-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Bray F., Center M. M., Ferlay J., Ward E., and Forman D., Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 61, 69–90 (2011). 10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. M. and Minerick A. R., Electrophoresis 32, 2512–2522 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Siegel R., Xu J., and Ward E., Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 60, 277–300 (2010). 10.3322/caac.20073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Deavers M., Patenia R., R. L.Bassett, Jr., Mueller P., Ma Q., Wang E., and Freedman R. S., J. Trans. Med. 4, 30 (2006). 10.1186/1479-5876-4-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortzak-Uzan L., Ignatchenko A., Evangelou A. I., Agochiya M., Brown K. A., St Onge P., Kireeva I., Schmitt-Ulms G., Brown T. J., Murphy J., Rosen B., Shaw P., Jurisica I., and Kislinger T., J. Proteome Res. 7, 339–351 (2008). 10.1021/pr0703223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann A. M., Havik E., Postma F. R., Beijnen J. H., Dalesio O., Moolenaar W. H., and Rodenhuis S., Annals Oncol. 9, 437–442 (1998). 10.1023/A:1008217129273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon S. P., Methods Mol. Med. 88, 133–139 (2004). 10.1385/1-59259-406-9:133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. K., Hamilton C. A., Anderson E. M., Cheung M. K., Baker J., Husain A., Teng N. N., Kong C. S., and Negrin R. S., Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197, 507 e501–505 (2007). 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nossov V., Amneus M., Su F., Lang J., Janco J. M., Reddy S. T., and Farias-Eisner R., Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199, 215–223 (2008). 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., R. C.Bast, Jr., Yu Y., Li J., Sokoll L. J., Rai A. J., Rosenzweig J. M., Cameron B., Wang Y. Y., Meng X. Y., Berchuck A., Van Haaften-Day C., Hacker N. F., de Bruijn H. W., van der Zee A. G., Jacobs I. J., Fung E. T., and Chan D. W., Cancer Res. 64, 5882–5890 (2004). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts P. C., Mottillo E. P., Baxa A. C., Heng H. H., Doyon-Reale N., Gregoire L., Lancaster W. D., Rabah R., and Schmelz E. M., Neoplasia 7, 944–956 (2005). 10.1593/neo.05358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creekmore A. L., Silkworth W. T., Cimini D., Jensen R. V., Roberts P. C., and Schmelz E. M., PloS one 6, e17676 (2011). 10.1371/journal.pone.0017676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketene A. N., Schmelz E. M., Roberts P. C., and Agah M., Nanomed.: Nanotechnol., Biol., Med. 8(1), 93 (2011). 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y. and Guo Z., Med. Eng. Phys. 25, 79–90 (2003). 10.1016/S1350-4533(02)00194-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker F. F., Wang X. B., Huang Y., Pethig R., Vykoukal J., and Gascoyne P. R. C., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 27, 2659–2662 (1994). 10.1088/0022-3727/27/12/030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker F. F., Wang X. B., Huang Y., Pethig R., Vykoukal J., and Gascoyne P. R. C., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 860–864 (1995). 10.1073/pnas.92.3.860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. C., Noshari J., Becker F. F., and Pethig R., IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 30, 829–834 (1994). 10.1109/28.297896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Wang X. B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R. C., Bba-Biomembranes 1282, 76–84 (1996). 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00047-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surowiec A. J., Stuchly S. S., Barr J. R., and Swarup A., IEEE Trans. Bio-Med. Eng. 35, 257–263 (1988). 10.1109/10.1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall H. J., Labeed F. H., Kazmi B., Costea D. E., Hughes M. P., and Lewis M. P., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 401, 2455–2463 (2011). 10.1007/s00216-011-5337-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewpiriyawong N., Yang C., and Lam Y. C., Biomicrofluidics 2, 34105 (2008). 10.1063/1.2973661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon Z., Mazur J., and Chang H. C., Biomicrofluidics 3, 44108 (2009). 10.1063/1.3257857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I. F., Chang H. C., and Hou D., Biomicrofluidics 1, 21503 (2007). 10.1063/1.2723669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lostumbo A., Mehta D., Setty S., and Nunez R., Exp. Mol. Pathol., 80, 46–53 (2006). 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagrath S., Sequist L. V., Maheswaran S., Bell D. W., Irimia D., Ulkus L., Smith M. R., Kwak E. L., Digumarthy S., Muzikansky A., Ryan P., Balis U. J., Tompkins R. G., Haber D. A., and Toner M., Nature 450, 1235–1239 (2007). 10.1038/nature06385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K. and Radbruch A., Cytometry 14, 384–392 (1993). 10.1002/cyto.990140407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E. B. and Singh A. K., Anal. Chem. 75, 4724–4731 (2003). 10.1021/ac0340612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C. F., Tegenfeldt J. O., Bakajin O., Chan S. S., Cox E. C., Darnton N., Duke T., and Austin R. H., Biophys. J. 83, 2170–2179 (2002). 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73977-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Duarte R., R. A.GorkinIII, Abi-Samra K., and Madou M. J., Lab Chip 10, 1030–1043 (2010). 10.1039/b925456k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapizco-Encinas B. H., Simmons B. A., Cummings E. B., and Fintschenko Y., Anal. Chem. 76, 1571–1579 (2004). 10.1021/ac034804j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo-Villanueva R. C., Perez-Gonzalez V. H., Davalos R. V., and Lapizco-Encinas B. H., Electrophoresis 32, 2456–2465 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos R. V., McGraw G. J., Wallow T. I., Morales A. M., Krafcik K. L., Fintschenko Y., Cummings E. B., and Simmons B. A., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 390, 847–855 (2008). 10.1007/s00216-007-1426-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gencoglu A. and Minerick A., Lab Chip 9, 1866–1873 (2009). 10.1039/b820126a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee H., Caldwell J. L., Sano M. B., and Davalos R. V., Biomed. Microdevices 11(5), 997 (2009). 10.1007/s10544-009-9317-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee H., Sano M. B., Henslee E. A., Caldwell J. L., and Davalos R. V., Lab Chip 10, 438–445 (2010). 10.1039/b920590j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmanzadeh A., Romero L., Shafiee H., Gallo-Villanueva R. C., Stremler M. A., Cramer S. D., and Davalos R. V., Lab Chip 12, 182–189 (2012). 10.1039/c1lc20701f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M. B., Caldwell J. L., and Davalos R. V., Biosens. Bioelectron 30, 13–20 (2011). 10.1016/j.bios.2011.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henslee E. A., Sano M. B., Rojas A. D., Schmelz E. M., and Davalos R. V., Electrophoresis 32, 2523–2529 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekka M., Laidler P., Gil D., Lekki J., Stachura Z., and Hrynkiewicz A. Z., Eur. Biophys. J. Biophy. 28, 312–316 (1999). 10.1007/s002490050213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S. E., Jin Y. S., Rao J., and Gimzewski J. K., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 780–783 (2007). 10.1038/nnano.2007.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling E. M., Zauscher S., Block J. A., and Guilak F., Biophys. J. 92, 1784–1791 (2007). 10.1529/biophysj.106.083097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth M. J., Lam W. A., and Fletcher D. A., Biophys. J. 90, 2994–3003 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.105.067496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., BioMEMS and Biomedical Nanotechnology (SpringerLink, 2007), pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Biomicrofluidics 4, 022811 (2010). 10.1063/1.3456626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklavčič D., Pavšelj N., and Hart F. X., Wiley Encyclopedia of Biomedical Engineering (John Wiley & Sons, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan L. A., Lu J., Wang L., Marchenko S. A., Jeon N. L., Lee A. P., and Monuki E. S., Stem Cells 26, 656–665 (2008). 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalak R. and Chien S., Handbook of Bioengineering (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Biomechanics, its Foundations and Objectives, edited by Y. C.Fung, N.Perrone, Anliker M.(University of California; San Diego, Office of Naval Research, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1972). [Google Scholar]

- Sukhorukov V. L., Arnold W. M. and Zimmermann U., J. Membr. Biol. 132, 27–40 (1993). 10.1007/BF00233049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. B., Huang Y., Gascoyne P. R., Becker F. F., Holzel R., and Pethig R., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1193, 330–344 (1994). 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90170-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. and Vykoukal J., Electrophoresis 23, 1973–1983 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda I., Tsukahara S., and Watarai H., Anal. Sci. 19, 27–31 (2003). 10.2116/analsci.19.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J., Lee J., Lee S. H., Park J., and Kim B., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 394, 801–809 (2009). 10.1007/s00216-009-2743-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]