Abstract

During a T cell response, the effector CTL pool contains two cellular subsets: short-lived effector cells (SLECs), a majority of which are destined for apoptosis, and the memory precursor effector cells (MPECs) that differentiate into memory cells. Understanding the mechanisms that govern the differentiation of memory CD8 T cells is of fundamental importance in the development of effective CD8 T cell-based vaccines. The strength and nature of TCR signaling along with signals delivered by cytokines like IL-2 and IL-12influence differentiation of SLECs and MPECs. A central question is, how are signals emanating from multiple receptors integrated and interpreted to define the fate of effector CTLs? Using genetic and pharmacological tools, we have identified Akt as a signal integrator that links distinct facets of CTL differentiation to the specific signaling pathways of FOXO, mTOR, and Wnt/β-catenin. Sustained Akt activation triggered by convergent extracellular signals evokes a transcription program that enhances effector functions, drives differentiation of terminal effectors, and diminishes the CTLs’ potential to survive and differentiate into memory cells. While sustained Akt activation severely impaired CD8 T cell memory and protective immunity, in vivo inhibition of Akt rescued SLECs from deletion and increased the number of memory CD8 T cells. Thus, the cumulative strength of convergent signals from signaling molecules such as TCR, costimulatory molecules, and cytokine receptors governs the magnitude of Akt activation, which in turn controls the generation of long-lived memory cells. These findings suggest that therapeutic modulation of Akt might be a strategy to augment vaccine-induced immunity.

Introduction

During an immune response, signals via the TCR along with appropriate costimulatory and inflammatory signals activate naïve T cells to proliferate and differentiate into effector cells (1–5). Following pathogen clearance, ~90% of the effector CD8 T cells are eliminated, and the remainder of the cells differentiate into long-lived memory T cells. These memory CD8 T cells are poised to proliferate and develop effector functions expeditiously, and confer rapid protective immunity to re-infection. Understanding the mechanisms that regulate the quantity and quality of CD8 T cell memory to intracellular pathogens is critical for the development of effective vaccines.

At the peak of the T cell response, the pool of effector CD8 T cells consists of least two subsets based on the expression of the IL-7 receptor (CD127) and KLRG1: the short-lived effector cells (SLECs; CD127LO and KLRG1HI) that are poised for apoptosis, and the memory precursor effector cells (MPECs; CD127HI and KLRG1LO) that differentiate into long-lived memory cells (6). The strength and duration of TCR signaling, exposure to cytokines like IL-2, IL-12, and IL-15, and asymmetric cell division are factors known to regulate the differentiation of SLECs and MPECs (1, 3, 4, 7–11). A critical question, however, is how are multiple extracellular signals factored in and interpretedin the cell fate decision of effector cells?

It has been reported that activation of the mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways have opposing effects on the fate of CTLs (12, 13), and the relative dominance of the competing pathways likely dictates the cell fate decision. However, our understanding of the mechanisms that control these competing signaling pathways is incomplete. The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway controls proliferation, differentiation, and survival in many cell types (14), and this pathway mediates signaling triggered by engagement of Ag receptors, costimulatory molecules and cytokine receptors (15). Recently, it was reported that Akt may also regulate the differentiation of CD8 effector T cells in vitro (16), but the in vivo relevance of this finding needs further evaluation (17). In this manuscript, we have systematically probed the role of the PI3K/Akt pathway in the differentiation of effector and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. First, we show differential Akt phosphorylation in virus-specific CD25HI and CD25LO subsets of CTLs, which differentiate into terminal effectors and memory cells respectively. Further, we document that sustained Akt activation in Ag-activated CD8 T cells promotes terminal differentiation and impairs CD8 T cell memory by altering specific signaling pathways that regulate distinct facets of CTL differentiation and cell survival. Conversely, in vivo inhibition of Akt mitigated the deletion of SLECs and augmented the number of effector memory cells. Based on the data presented in this manuscript, we propose that Akt integrates convergent signals from the TCR and receptors for cytokines like IL-2 and IL-12, and the magnitude of Akt activation dictates the differentiation of CTLs into terminal effectors or memory cells. These findings have significant implications in development of vaccines and treatment of T cell-dependent immunopathologies.

Materials and methods

Mice and viral infection

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute or the Jackson Laboratory. Akt transgenic mice that express constitutively active (CA) Akt in T cells were a kind gift from Dr. Hotchkiss (Washington University) (18). P14/Ly5.1 mice that express the transgenic TCR specific for the Db-restricted GP33 epitope of LCMV (provided by Dr. Murali-Krishna, University of Washington) were crossed with Akt transgenic mouse to derive the P14/Akt transgenic mouse. The IL-7 receptor transgenic mice were kindly provided by Dr. Singer (National Institutes of Health) (19), which were crossed with P14/Akt mice to generate the P14/IL-7R or P14/Akt/IL-7R transgenic mice. Mice were infected intraperitoneally (I/P) with 2×105 PFU of the LCMV Armstrong strain to induce an acute infection. Infectious LCMV was quantified by a plaque assay on Vero cells as described previously (20). Recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the LCMV glycoprotein (VV-GP) (kindly provided by Dr. Whitton, Scripps Research Institute) (21) was injected I/P at a dose of 2×106 PFU. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the approved protocols of the institutional animal care committee.

Adoptive transfer of P14 CD8 T cells

P14/Ly5.1 CD8 T cells were purified from spleen of P14/WT, P14/Akt, P14/IL-7R, or P14/Akt/IL-7R mice using the MACS protocol (Miltenyi Biotec). Purified P14 CD8 T cells (104 cells) were adoptively transferred into congenic Ly5.2 C57BL/6 mice as before (11, 22). One day after cell transfer, recipient mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong.

Flow cytometry and cell surface staining

Mononuclear cells from spleen, livers, or lymph nodes were prepared using standard techniques. MHC class I tetramers, specific for the LCMV epitopes NP396–404 (NP396) and GP33–41 (GP33) were prepared and used as described previously (23). Briefly, cells were stained with anti-CD8 and MHC class I tetramers and/or anti-CD45.1 (Ly5.1). In some experiments, cells were co-stained with anti-CD44, anti-CD62L, anti-CD43, anti-CD69, anti-KLRG1, anti-CD127, and anti-LFA-1 Abs. All Abs were purchased from BD Biosciences or eBioscience except the anti-KLRG1 Ab (Southern Biotech). Samples were analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Intracellular staining

For intracellular cytokine staining, splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with LCMV epitope peptides in the presence of brefeldin A for 5 hrs. After culture, cells were stained for cell surface molecules and intracellular IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 using a Cytofix/Cytoperm intracellular staining kit (BD Biosciences). To stain for intracellular Bcl-2 and granzyme B, splenocytes were stained for cell surface molecules and subsequently permeabilized and stained for intracellular proteins using Anti-Mouse Bcl-2 Set (BD Biosciences) and anti-Granzyme B Ab (Invitrogen).

Phospho-specific staining

Splenocytes were stained with anti-CD8, anti-CD45.1 in conjunction with MHC class I tetramers. Following surface staining, cells were fixed and lysed (PhosFlow kit, BD Biosciences), and washed in 2% FBS/PBS After blocking with 10% goat serum in 2% BSA/PBS, cells were stained for intracellular phospho-specific proteins including p-Akt (T308), p-FoxO1/O3 (T24/T32), p-mTOR (S2448), and Tcf1 at a 1:50 dilution of the Ab. As negative controls, cells were stained with phospho-specific Abs pre-incubated with the specific blocking peptide. Following incubation with primary Abs, cells were washed and incubated with an anti-rabbit Ab (Invitrogen). All phospho-specific Abs were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Staining for T-bet and Eomes was done as described above, and Abs were purchased from eBioscience.

In vitro activation and Western blot analysis

Splenocytes from B6 mice were enriched for CD8 T cells using by CD8a+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). For in vitro activation, purified cells were stimulated for 2 days with plate-bound anti-CD3 (300ng/well) and anti-CD28 (100ng/well) Abs (Southern Biotech) in the presence or absence of IL-12 (10ng/ml; R&D Systems). After activation, CD8 T cells were harvested, and resuspended in a RIPA buffer. An equal amount (40µg/sample) of total protein was subjected to Western blot analysis. The HRP-conjugated Abs were detected by amplification with West-Zol (Intron Biotechnology) reagents and visualized by exposure to X-ray film. Beta-actin was used as an internal control for normalization.

Microarray and quantitative RT-PCR

Splenocytes from uninfected P14/WT or P14/Akt mice were stained with anti-CD8 and anti-Ly5.1, and CD8 T cells were sorted using a FACSAria II instrument (BD Biosciences). Purified Ly5.1+ CD8 T cells from P14/WT or P14/Akt mice were transferred into B6 mice, which were subsequently infected with LCMV Armstrong. At day 8 after infection, splenocytes were stained with anti-CD8, anti-Ly5.1, anti-KLRG1, and anti-CD127. Following staining, SLECs and MPECs were sorted using the FACSAria II instrument; the purity of the sorted cells was >95%. Total RNA was extracted from the sorted cells by Trizol reagent, and subsequently cleaned up by using RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed and the cDNA was analyzed using the Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array at the University of Wisconsin Gene Expression Center. Statistically significant differences in gene expression were identified with Multiple Experiment Viewer v4.6 and Microsoft Excel. The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE36168 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE36168). For quantitative RT-PCR, cDNA was synthesized from the isolated RNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Equivalent amounts of cDNA (as determined by 18S rRNA measurements by quantitative PCR) were amplified in 35 cycles of PCR with SYBR green using intron-spanning primers designed for each gene. Applied Biosystems 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used for this analysis.

Pharmacologic inhibitors and IL-2 treatment

Rapamycin (LC Laboratories) was diluted in sterile PBS, and injected IP daily on days 1–35 after LCMV infection at a dose of 75ug/kg body weight. A-443654, a selective inhibitor of Akt, was a kind gift from V.L. Giranda (Abbott Laboratories) (24). The Akt inhibitor A-443654 was diluted in 0.2% HPMC and administered subcutaneously twice a day for 8 days at a dose of 15mg/kg/day. Mice were injected with 15,000 IU of recombinant human IL-2 (TECIN/Roche; provided by the National Cancer Institute) or PBS IP twice a day from days 0–7 after LCMV infection.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data were analyzed using commercially available statistical software (SigmaPlot). Groups were compared by Student’s t test, and significance was defined at P <0.05.

Results

Dynamics of Akt phosphorylation in vivo in virus-specific CD8 T cells

First, we examined the in vivo dynamics of Akt phosphorylation in Ag-specific CD8 T cells during an acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection. Akt phosphorylation (Thr308) in LCMV-specific TCR transgenic (tg) P14 CD8 T cells peaked at days 5 post-infection (PI), and subsided thereafter (Fig. 1A), which mirrored the kinetics for LCMV level in the serum (data not shown). This data along with previous report15 suggests that the Akt phosphorylation can be triggered by antigenic stimulation in vivo.

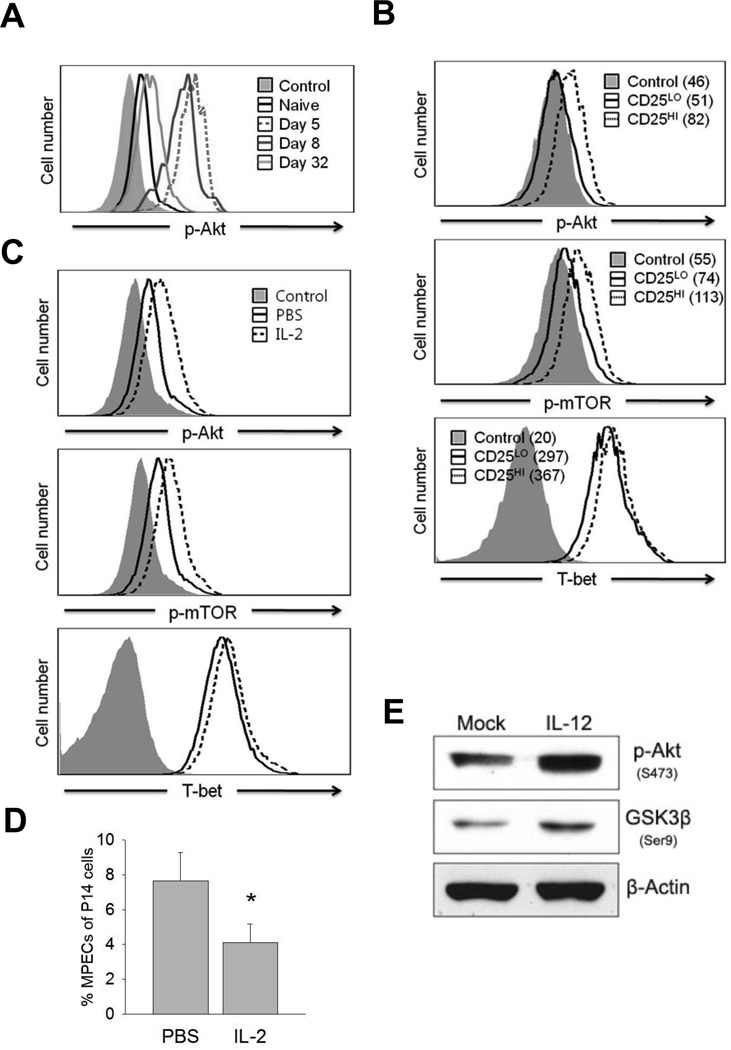

FIGURE 1. In vivo dynamics of Akt phosphorylation in Ag-specific CD8 T cells.

A, Dynamic alterations in Akt phosphorylation (T308) measured by phospho-specific staining. Naïve P14 (Ly5.1) cells were adoptively transferred into B6 mice (Ly5.2), which were subsequently infected with Arm strong strain of LCMV. The FACS histograms showing p-Akt staining in panel A are gated on Ly5.1+ P14 CD8 T cells from mice infected with LCMV Armstrong. Control represents staining with p-Akt Ab that was pre-blocked with the specific antigenic peptide. B, B6 mice that were recipients of P14 cells were infected with LCMV-Armstrong. At day 3.5 after infection, P14 CD8 T cells in spleen were analyzed for CD25, T-bet, and phosphorylation of Akt (T308) and mTOR (S2448) directly ex vivo. Data are representative of two independent experiments and the numbers are the calculated ∆MFIs. C and D, Naïve P14 CD8 T cells were transferred into congenic B6 mice and infected with LCMV Armstrong. Cohorts of mice were treated with IL-2 or the vehicle (PBS) daily between days 0–7 PI. At day 8 PI, p-Akt, p-mTOR, and T-bet levels in splenic P14 CD8 T cells were quantified as in panel A. The histograms in panel C are gated on P14 CD8 T cells; data in panel D shows the percentages of MPECs among P14 CD8 T cells in spleen (mean ± SD). E, CD8 T cells purified from spleen of naïve B6 mice were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 48 hr. in the presence or absence of IL-12. Picture shows immunoblots of p-Akt and p-GSK3β. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are presented; *P<0.05.

Seminal studies have demonstrated that cytokines such as IL-2 and IL-12 promote the differentiation of SLECs by inducing the transcription factor T-bet (4, 8, 11, 25). Ahmed’s group showed that CD8 T cells expressing high levels of CD25receive sustained IL-2 signals, express high levels of T-bet, and differentiate into SLECs (11). Therefore, we evaluated the relationship between CD25 expression and Akt phosphorylation in Ag-specific CD8 cells during an acute LCMV infection.CD8 T cells with high CD25expression clearly displayed higher levels of phosphorylation on Akt and its potential substrate mTOR, and increased levels of T-bet, as opposed to CD25Lo CD8 T cells (Fig.1B). Moreover, continued IL-2 signaling induced by exogenous IL-2 treatment sustained the activation of Akt and mTOR, enhanced the expression of T-bet (Fig.1C), and reduced the percentages of LCMV-specific MPECs in vivo (Fig.1D). Additionally, CD8 T cells exposed to IL-12 exhibited enhanced phosphorylation of Akt and the downstream kinase GSK3β (Fig.1E). Taken together, these data link increased phosphorylation of Akt to sustained cytokine signaling in CD8 T cells, and their differentiation into SLECs.

Sustained Akt activation drives terminal differentiation and loss of CD8 T cell memory, and impairs protective immunity

To examine whether sustained Akt activation regulated CD8 T cell differentiation in vivo, we derived the P14/Akt mice by crossing P14 TCR tg mice with mice that express the constitutively active Akt (CA-Akt) transgene in T cells (26). We first confirmed that naive P14/Akt CD8 T cells showed increased Akt phosphorylation compared to naïve P14/WT CD8 T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Following an acute LCMV infection, CA-Akt did not affect the primary expansion of donor P14 CD8 T cells (Fig. 2A), or the expression of molecules such as CD44, CD43, CD69, and CD62L on effector cells (Fig. 2B). Notably, the expression of LFA-1 on P14/Akt effector cells was higher than in P14/WT effector cells. The Ag-triggered expression of IFN-γ and Granzyme B levels werehigher in P14/Akt CD8 T cells (Fig. 2C). Next, we examined whether CA-Akt affected the generation of memory CD8 T cells. At day 53 PI, remarkably, the frequency of P14/Akt CD8 T cells in the spleen were ~50-fold lower than the P14/WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 2D). We observed the exaggerated contraction of P14/Akt CD8 T cells and striking erosion of CD8 T cell memory in spleen (Fig. 2E), lymph nodes, and liver (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Next, we examined whether CA-Akt regulated the responses of polyclonal CD8 T cells following infections with LCMV or vaccinia virus. Similar to monoclonal P14/Akt CD8 T cells, polyclonal virus-specific CD8 T cells expressing CA-Akt showed normal primary expansion and differentiation into effectors, but underwent exaggerated contraction after day 8 PI (Supplemental Fig. 2). Strikingly, upon challenge with LCMV Clone 13, loss of CD8 T cell memory in LCMV-immune CA-Akt mice significantly compromised the recall responses and viral control (Supplemental Fig. 3). Together, these data strongly suggested that sustained activation of Akt in CD8 T cells impaired generation of CD8 T cell memory and protective recall responses without affecting the primary expansion or effector functions.

FIGURE 2. Normal expansion but loss of CD8 T cell memory due to sustained Akt activation.

Purified wild type (P14/WT) or CA-Akt transgenic (P14/Akt) P14 CD8 T cells were transferred into B6 mice, followed by LCMV Armstrong infection. A, FACS plots show percentages of donor P14 CD8 T cells in spleen at day 8 PI. B, Cell surface phenotype of donor P14 CD8 T cells. C, Quantification of IFN-γ and Granzyme B expression after ex vivo peptide stimulation or directly ex vivo respectively. Numbers are the calculated ∆MFIs D, Frequency of donor P14/WT or P14/Akt cells in spleen of B6 mice at 53 days PI. E, Kinetics of P14/WT or P14/Akt response to an acute LCMV Armstrong infection (mean ± SD). F, At days 8 and 17 after infection, donor P14 CD8 T cells were analyzed for KLRG1 and CD127 expression to visualize MPECs and SLECs; numbers are the percentages of cells among P14 CD8 T cells. G, At day 8 and 15 PI, P14 CD8 T cells were analyzed for CD122 expression and intracellular levels of Bcl-2 directly ex vivo. Data are representative of three independent experiments with 4–5 replicates; *P<0.05.

Next, we investigated whether CA-Akt impaired the generation of memory CD8 T cells by disrupting the differentiation of MPECs. Data in Fig. 2F show that MPECs were barely detected among P14/Akt effector CD8 T cells at days 8 and 17 PI, as a consequence of a severe defect in the expression of the IL-7 receptor (CD127). Additionally, P14/Akt effector CD8 T cells displayed marked reduction in Bcl-2 and CD122 levels, as compared to those in P14/WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 2G). Thus, diminished IL-7- and/or IL-15-dependent survival signals might have contributed to the exaggerated loss of P14/Akt CD8 T cells (27).

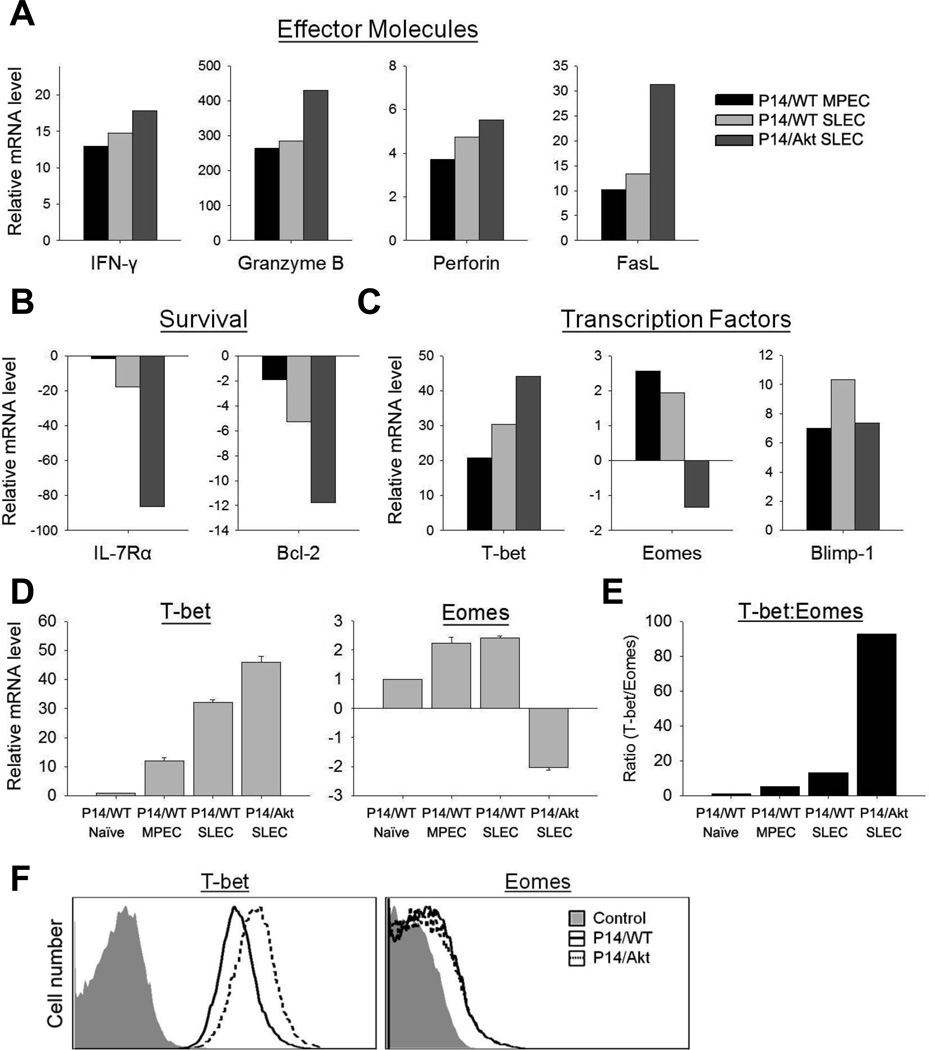

Sustained Akt activation dramatically alters the transcriptome of virus-specific CD8 T cells

To decipher the transcriptional basis of CA-Akt actions, we compared the transcriptomes of P14/WT and P14/Akt naïve and effector CD8 T cells. The transcriptomes of naïve P14/WT and P14/Akt CD8 T cells were largely similar. However, there were marked differences in the expression of several key molecules between P14/WT MPECs, P14/SLECs, and P14/Akt SLECs. The expression of genes for effector molecules IFN-γ, granzyme B, perforin, and Fas ligand in P14/Akt SLECs were substantially higher than in P14/WT MPECs or SLECs (Fig. 3A). Conversely, the expression of molecules associated with T cell survival, CD127 and Bcl-2 was markedly lower in P14/Akt SLECs, as compared to P14/WT MPECs or SLECs (Fig. 3B). These data indicated that CA-Akt promoted expression of effector molecules, but repressed pro-survival genes in effector CD8 T cells. The balance between the transcription factors T-bet and Eomes might control the fate of effector CD8 T cells: terminal differentiation versus memory (8, 28, 29). Fig. 3C illustrates the step-wise increase in the expression levels of T-bet in P14/WT MPECs, P14/WT SLECs, and P14/Akt SLECs. Conversely, P14/WT MPECs, P14/WT SLECs, and P14/Akt SLECs displayed an incremental decline in the levels of Eomes (Fig. 3C). Note the striking increase in the T-bet: Eomes ratio in P14/Akt SLECs (Fig. 3E). The expression of Blimp-1, another regulator of T cell differentiation (30), was not different in P14/Akt SLECs (Fig. 3C). Alterations in gene expression induced by CA-Akt were confirmed by real-time PCR and/or flow cytometry (Fig. 3D–3F). Taken together, these data suggested that CA-Akt likely drove terminal differentiation of P14 CD8 T cells and apoptosis by disrupting the balance between T-bet and Eomes, and repressing the expression of survival factors (CD127, CD122, and Bcl-2).

FIGURE 3. Sustained activation of Akt alters the transcriptome of effector CD8 T cells.

A–D, Naïve CD8 T cells were sorted from spleens of uninfected P14/WT or P14/Akt mice. Purified P14/WT or P14/Akt Ly5.1+ CD8 T cells were transferred into B6 (Ly5.2) mice, which were subsequently infected with LCMV Armstrong. At day 8 PI, donor P14/WT or P14/Akt SLECs and MPECs were sorted from spleen. RNA was isolated from sorted cells and subjected to DNA microarray analysis (A–C) or qRT-PCR (D, mean ± SD). Data are presented as fold over P14/WT naïve with P14/WT naïve mRNA levels normalized to 1. E, qRT-PCR data in panel D was used to calculate the T-bet: Eomes ratio. F, At day 8 after LCMV infection, splenocytes from P14/WT and P14/Akt mice were harvested and the levels of T-bet and Eomes proteins in P14 CD8 T cells were quantified directly ex vivo by flow cytometry; negative control represents staining with isotype control Abs.

Sustained Akt phosphorylation inactivates FOXO transcription factors, reduces IL-7 receptor expression, and impairs the survival of MPECs

The FOXO family of transcription factors, which drive the expression of CD62L, CCR7 and IL-7R genes in T cells (31), is a direct substrate of Akt. Phosphorylation of FOXOs by Akt results in their inactivation by cytoplasmic re-localization, and consequent reduction in the expression of their target genes. Indeed, impaired expression of IL-7R on P14/Akt effector CD8 T cells was associated with CA-Akt-induced phosphorylation of FOXO1/3 (Fig. 4A). Since expression of IL-7Rα is necessary for generating long-lived memory CD8 T cells (32–34), we tested whether enforced expression of IL-7Rα would rescue P14/Akt effector CD8 T cells from exaggerated contraction. P14/Akt mice were crossed with IL-7R transgenic mice to derive the triple transgenic P14/Akt/IL-7R mice. The responses of P14/WT, P14/IL-7R, P14/Akt, and P14/Akt/IL-7R CD8 T cells to an acute LCMV infection are shown in Fig. 4B. As reported before, the expansion and contraction of P14/WT and P14/IL-7R CD8 T cells were similar (34). P14/Akt CD8 T cells displayed exaggerated contraction, but notably, the extent of contraction of P14/Akt/IL-7R CD8 T cells (~120-fold) between days 8 and 36 PI was substantially reduced, as compared to that of P14/Akt CD8 T cells (~1,900-fold). Strikingly, transgenic expression of IL-7R was clearly more effective in mitigating the loss of KLRG1LO(MPECs) P14/Akt cells, as compared to that of P14/Akt KLRG1HI(SLECs) cells (Fig. 4C, 4D). In addition to the prominent rescue of KLRG1LO P14/Akt CD8 T cells, IL-7R expression enhanced Ag-induced IL-2 production (Fig. 4E). These data suggested that impaired expression of IL-7R, a likely consequence of FOXO inactivation (31), might underlie the loss of KLRG1LO P14/Akt CD8 T cells. Surprisingly, the increased survival of P14/Akt/IL-7R CD8 T cells was not associated with restoration of Bcl-2 expression to the levels observed in P14/WT cells (Fig. 4F). This result implies that IL-7R signaling might have protected P14/Akt CD8 T cells from apoptosis through a Bcl-2-independent mechanism.

FIGURE 4. Rescue of CA-Akt MPECs by transgenic expression of IL-7 receptor.

A, At day 8 after LCMV Armstrong infection, phosphorylation on FoxO1/O3 (T24/T32)in donor P14/WT or P14/Akt CD8 T cell was quantified by phospho-specific staining. B–F, CD8 T cells purified from P14/WT, P14/ IL-7R, P14/Akt, or P14/Akt/IL-7R mice were transferred into B6 mice, which were subsequently infected with LCMV. The numbers of total (B), KLRG1HI (C), and KLRG1LO P14 cells were quantified at different days after LCMV infection (D, mean ± SD). E, The number of donor P14 CD8 T cells that produced both IFNγ and IL-2 was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining. F, Bcl-2 expression in donor P14 CD8 T cells.* denotes significant difference (P<0.05) between P14/Akt and P14/Akt/IL-7R groups. Data is representative of two independent experiments with 4–5 replicates.

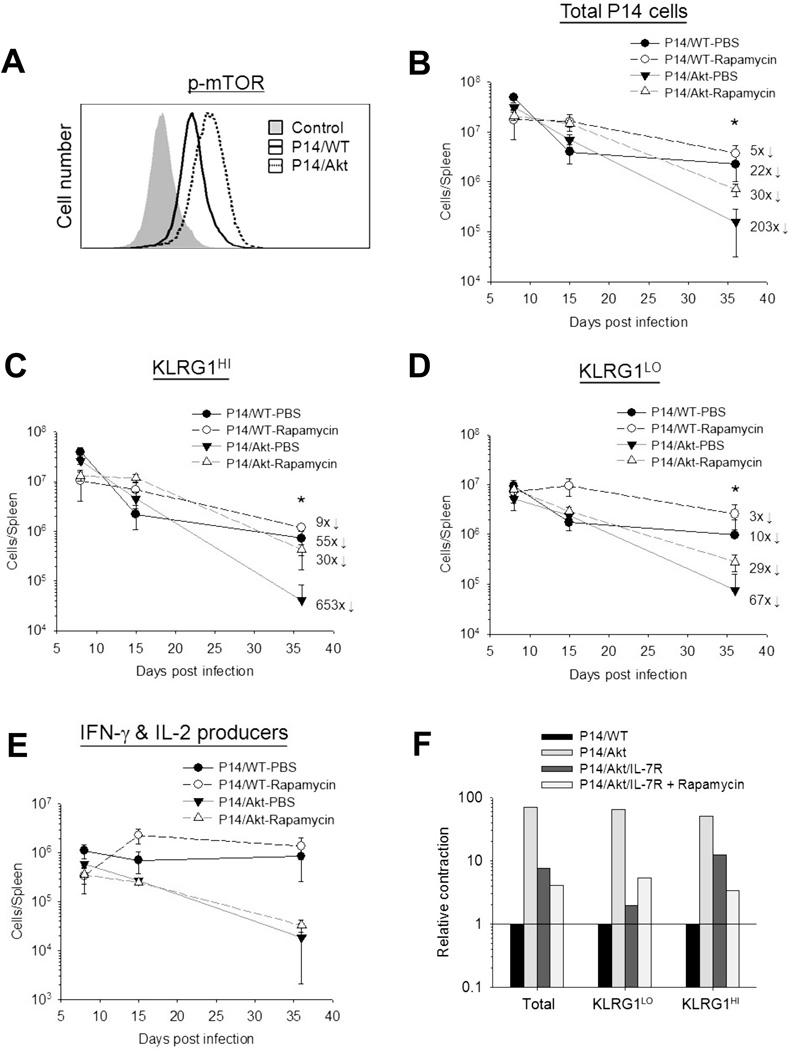

Sustained Akt activation phosphorylates mTOR and exaggerates the loss of SLECs

Another important substrate for Akt is the tuberous sclerosis complex, which regulates the activity of mTOR complex 1(mTORC1). mTORC1 signaling is known to promote differentiation of CD8 T cells into SLECs by a mechanism involving T-bet (8, 13), and in vivo inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin treatment enhances the number of memory CD8 T cells (13), but it is unclear whether Akt regulates CTL differentiation in vivo via mTOR. P14/Akt effector CD8 T cells clearly displayed increased phosphorylation (Ser2448) of mTOR (Fig. 5A) along with elevated levels of T-bet (Fig.3F), as compared to effector P14/WT CD8 T cells. To test whether CA-Akt-induced activation of mTOR activity contributed to the loss of CD8 T cell memory, we adoptively transferred P14/WT or P14/Akt CD8 T cells into congenic C57BL/6 mice, and treated these mice with rapamycin daily between days 1 and 35 after LCMV infection. Rapamycin treatment reduced the contraction of both KLRG1HI and KLRG1LO effector P14/WT CD8 T cells (Fig. 5B-5D). Interestingly, rapamycin reduced the contraction of KLRG1HI P14/Akt CD8 T cells to a much greater degree, as compared to that of KLRG1LO P14/Akt CD8 T cells (Fig. 5C, 5D). However, rapamycin treatment did not rescue the IL-2-producing ability of P14/Akt CD8 T cells (Fig. 5E). These findings suggested that CA-Akt-driven mTOR activation accentuated the loss of KLRG1HI effector CD8 T cells, with less remarkable effects on the contraction of KLRG1LO cells. The effects of mTOR inhibition by rapamycin treatment also included downregulation of T-bet levels P14/Akt effector CD8 T cells. Next, we investigated whether transgenic expression of IL-7R and mTOR inhibition would have additive or synergistic effects on the rescue of P14/Akt effector CD8 T cells. Interestingly, inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin treatment did not further reduce the contraction of KLRG1LO P14/Akt/IL-7R CD8 T cells (Fig. 5F). Nor did transgenic expression of IL-7R enhance the pro-survival effects of rapamycin on KLRG1HI P14/Akt CD8 T cells (Fig. 5F). These data suggested that CA-Akt controls the homeostasis of KLRG1LO(MPECs) and KLRG1HI SLECs by distinct pathways, the FOXO and mTOR respectively.

FIGURE 5. Role of mTOR in the exaggerated loss of CA-Akt P14 CD8 T cells.

A, At day 8 after LCMV Armstrong infection, phosphorylation on mTOR (S2448) in donor P14/WT or P14/Akt CD8 T cell was quantified by phospho-specific staining. B–D, Purified P14/WT or P14/Akt CD8 T cells were transferred into B6 mice, and subsequently infected with LCMV. Cohorts of mice were treated daily with PBS or rapamycin (from day 1 to 35 PI). The numbers of donor P14 CD8 T cells with the KLRG1HI and KLRG1LO phenotype were quantified by flow cytometry (mean ± SD). E, P14 CD8 T cells that produced both IFNγ and IL-2 was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining. * denotes significant difference (P<0.05) between Akt-PBS and Akt-Rapamycin groups. Numbers indicate fold contraction between days 8 to day 36 PI. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 4 replicates. F, CD8 T cells purified from P14/WT, P14/ IL-7R, P14/Akt, or P14/Akt/IL-7R mice were transferred into B6 mice, which were subsequently infected with LCMV. Cohorts of mice in each group were treated with rapamycin as in B and the numbers of KLRG1HI or KLRG1LO P14 CD8 T cells in spleen were enumerated by flow cytometry at days 8 and 35 PI. Data is the calculated fold contraction between day 8 and 35 PI, relative to P14/WT cells.

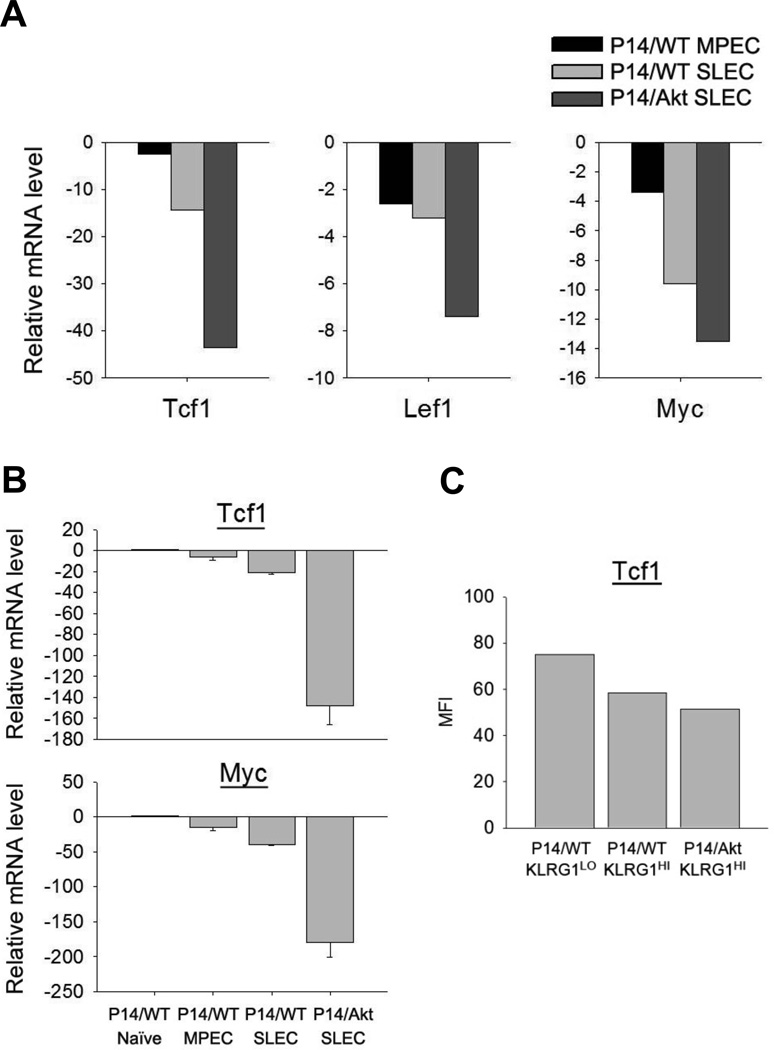

Akt activation regulates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in CD8 T cells in vivo

Because the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays an important role in promoting the survival and homeostatic proliferation of memory CD8 T cells (12, 35, 36), and Akt is known to regulate this pathway (37), we tested whether sustained Akt signaling also repressed the Wnt/β-catenin-induced transcription by quantifying the expression of target genes: Tcf1, Lef1 and myc. The expression of Tcf1, Lef1 and myc in P14/WT effector CD8 T cells was lower than in naïve P14/CD8 T cells. Interestingly, in P14/WT CD8 T cells, these genes showed reduced expression in SLECs compared to MPECs (Fig. 6A, 6B), which may explain the poor survival and homeostatic proliferation of SLECs. Importantly, the expression of these genes (Fig.6A,6B) and Tcf1 protein (Fig.6C) in P14/Akt SLECs was lower than in P14/WT SLECs. These data suggested that CA-Akt-induced impairment of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway aggravated the survival and homeostatic proliferation of memory P14/Akt CD8 T cells.

FIGURE 6. Impaired expression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling-associated genes in P14/Akt CD8 T cells.

A and B, Naïve P14/WT CD8 T cells, naïve P14/Akt CD8 T cells, P14/WT SLECs, P14/WT MPECs, and P14/Akt SLECs were sorted from spleens; SLECs and MPECs were sorted at day 8 after LCMV infection. mRNAs were isolated from each sample and subjected to DNA microarray analysis (A) or qRT-PCR (B, mean ± SD). Data are presented as fold over WT naïve with naïve mRNA levels normalized to 1. C, At day 8 after LCMV infection, the protein level for Tcf1 was assessed by flow cytometry. Data show MFIs for Tcf1 staining in the indicated cell population.

In vivo inhibition of Akt enhances effector memory CD8 T cells

Since sustained Akt activation promoted terminal differentiation of effector cells, we hypothesized that inhibition of Akt activity would impede this process and enhance the number of memory CD8 T cells. To test this hypothesis, we treated LCMV-infected mice with a selective Akt inhibitor A-443654 (24) during the first 8 days PI.A-443654 reduced the phosphorylation of Akt substrates mTOR and FOXO1/O3 in CD8 T cells within 2 hours in vitro (Supplemental Fig.4). In vivo inhibition of Akt by treatment of LCMV-infected mice with A-443654 reduced mTOR phosphorylation and the T-bet: Eomes ratio in P14 effector CD8 T cells (Fig.7A,7B). At day 35 PI, the numbers of P14 CD8 T cells in spleen of A-443654-treated mice were significantly (P=0.052) higher than in the spleen of vehicle-treated mice (Fig.7C). Notably, Akt inhibition led to a selective and significant increase in the number of P14 CD8 T cells that displayed an SLEC or a CD62LLO effector memory (EM) phenotype (Fig.7D,7E). From these data, we infer that Akt inhibition rescued a fraction of the SLECs from terminal differentiation and apoptosis, leading to their survival and subsequent transition into EM cells. However, it should be noted that the number of EM cells are greater than the number of SLECs in both vehicle- and A-443654-treated mice, which suggested that EM cells emerged from SLECs and MPECs. Although it is unlikely that A-443654 completely abolished Akt activity in CD8 T cells, these studies strongly suggested that effective therapeutic blockade of Akt is a viable approach to enhance vaccine-induced CTL memory.

FIGURE 7. Akt inhibition enhances CD8 T cell memory.

Cohorts of LCMV Armstrong-infected mice were treated twice a day with the vehicle or the Akt inhibitor (A-443654) between days 0–7 PI. At day 8 PI, the intracellular levels of phospho-mTOR (A), Eomes (B), and T-bet (B) were quantified by flow cytometry. C–E, At day 35 PI, the total number of donor P14 CD8 T cells (C) or the number of P14 CD8 T cells with the SLEC or MPEC phenotype (D) or the number of P14 CD8 T cells with the central memory (CD62LHI; TCM) or effector memory (CD62LLO; TEM) phenotype (E) in spleen were quantified by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM.). Data are from 4 mice/group.

Discussion

While it is well established that effector cells differentiate into long-lived memory CD8 T cells (38–40), deciphering the mechanisms that govern the cell fate decision of effector CD8 T cells (death versus differentiation into memory CD8 T cells) is currently a topic of intense investigation. Several extrinsic factors (e.g. Ag, IL-2, and IL-12) and cellular signaling pathways (e.g. mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin) have been implicated in regulating differentiation of memory CD8 T cells (1, 3, 4, 8, 11, 12, 36, 41). However, we do not fully understand the signaling circuitry involved in orchestrating the differentiation of effector and memory CD8 T cells. Specifically, it is unclear whether diverse extracellular signals trigger coincident distinct biochemical pathways or if the differentiation phenotype develops from a signaling hub that then engages common downstream signaling pathways. A common theme in biochemical events triggered by the TCR, CD28, the IL-2 receptor complex, and the IL-12 receptor is the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (15, 42). Understanding the role of P3K/Akt pathway in memory CD8 T cell differentiation is the focus of this manuscript. Our initial finding of differential Akt activation in CD25HI and CD25LO CD8 T cells that have disparate cell fates, underpinned our hypothesis that the magnitude of Akt activation regulates the differentiation of these CD8 T cell subsets into terminal effectors and MPECs respectively. Here, we report that sustained Akt activation causes profound alteration of gene expression in effector CD8 T cells that is reminiscent of terminal differentiation, consequent to the modulation of biochemical pathways including the FOXO, mTOR, and Wnt/β-catenin. Conversely, inhibition of Akt activity led to a significant enhancement in the number of memory CD8 T cells. The key point of this paper is that diverse extracellular signals converge to activate Akt, and differential Akt activation evokes the heterogeneity and disparate fate of effector cells. These findings have strong implications in the design of CD8 T cell-based vaccines against intracellular pathogens and cancer.

Studies from Ahmed’s group have shown that the duration of IL-2 signaling controls the fate of effector cells during Ag-driven clonal expansion (11). The signaling basis for the preferential differentiation of CD25HI cells and CD25LO CD8 T cells into terminal effectors and memory CD8 T cells in vivo remains unknown. Here, we link heterogeneity in CD25 expression to differential activation of Akt, and the functional states of its downstream substrates mTOR and FOXO1/O3 in vivo. Additionally, we find that prolonged exposure to IL-2 sustains activation of Akt/mTOR and reduces the number of MPECs, presumably by promoting differentiation of SLECs. Taken together, these findings strengthen our hypothesis that sustained Akt activation promotes the differentiation of terminal effectors during a CD8 T cell response.

Recently, it was reported that Akt activation is required for development of CTL effector functions (16). Further to this, it was shown that inhibition of Akt activity in vitro not only diminished effector functions, but also induced, in Ag-activated CD8 T cells, a phenotype reminiscent of memory CD8 T cells (16). Although these studies provided important insights, the role of Akt in the differentiation of effector and memory CD8 T cells was not formally tested in vivo. To mimic sustained Akt activation in CD8 T cells, we utilized CD8 T cells that express the CA-Akt. Although sustained Akt activation in CD8 T cells did not affect clonal expansion or development of effector functions, we did observe that CA-Akt effector CD8 T cells have an abbreviated life span and fail to differentiate into long-lived memory cells.Kaech’s group has reported similar findings but the underlying mechanisms were not fully elucidated (43). The failure to form memory CD8 T cells as a consequence of CA-Akt was associated with profound reduction in IL-7 receptor, CD122, and Bcl-2 levels in effector CD8 T cells. Transgenic expression of IL-7 receptor could rescue a majority of the CA-Akt MPECs but not all SLECs from deletion, which suggest that sustained Akt activation compromises the survival of MPECs by ablating IL-7 receptor expression. The dramatic loss of IL-7 receptor expression induced in CA-Akt CD8 T cells is likely a consequence of impaired FOXO1-dependent transcription (31, 44). Surprisingly, restoration of IL-7 receptor signaling did not rescue Bcl-2 expression in CA-Akt CD8 T cells, which suggests that downregulation of Bcl-2 could not be attributed to loss of IL-7 receptor per se, and might be a consequence of diminished levels of CD122 and/or STAT5 signaling triggered by exposure to cytokines like IL-15 (9, 43, 45). An important functional attribute of MPECs is the ability to produce IL-2 (7), and CA-Akt diminished the IL-2-producing ability of effector CD8 T cells. The enforced expression of IL-7 receptor substantially rescued the IL-2-producing ability of CA-Akt MPECs, which imply that IL-7 promotes IL-2 production or promotes the survival of IL-2-producing CD8 T cells.

One striking feature of the transcriptome of CA-Akt effector cells is the marked elevation in the transcripts for effector molecules IFN-γ, Fas L, perforin and the transcription factor T-bet. T-bet is a unique transcription factor that promotes effector functions and possibly terminal differentiation of CTLs (4, 28). However, it is unclear whether development of effector functions is mechanistically linked to terminal differentiation of CTLs. It is quite possible that these two events are coincident because they are both regulated by the same factor, T-bet. Alternatively, switching of energy metabolism pathways due to execution of effector functions might control differentiation of CTLs (29). Since Akt blockade or T-bet deficiency impairs CTL effector functions (16, 28), it is likely that Akt promotes the expression of effector molecules by inducing T-bet, which also might drive differentiation of CTLs into terminal effectors. Currently, we do not know how T-bet drives differentiation of CTLs into terminal effectors, but possible mechanisms would include regulation of trafficking, metabolism, and survival. Like T-bet, the transcription factor Eomes is also known to promote CTL effector functions, but Eomes appear to oppose the pro-terminal differentiation effects of T-bet (28, 46). In CA-Akt CTLs, elevated levels of T-bet were associated with lower levels of Eomes, and consequently a marked increase in the T-bet:Eomes ratio, which is believed to favor terminal differentiation over memory (29). Since mTOR inhibition subdued T-bet expression and substantially mitigated the loss of CA-Akt effectors, it is conceivable that inflated T-bet levels in CA-Akt effectors are linked to hyper-activation of mTOR and exaggerated loss of SLECs. Notably, another hallmark feature of CA-Akt effector cells is the striking reduction in the levels of transcripts for Tcf1, Lef1, and myc genes, suggestive of diminished signaling via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Because Tcf1 has been reported to be essential for optimal expression of Eomes and CD122, the reduction in the expression of these molecules in CA-Akt effector cells may be attributed to diminished Tcf1 levels (47). We propose that deletion of terminal effector cells is a consequence of a combination of mechanisms regulated by Akt activation, including disabling of FOXO/Wnt/β-catenin pathways and enhancement of mTOR activity. This in turn would be expected to alter cell survival, trafficking, and metabolism, culminating in the demise of SLECs.

While our studies with CA-Akt CD8 T cells demonstrate that hyper-activation of Akt exacerbates the loss of effector CTLs, it was equally important to understand the physiological significance of Akt activation for memory development. Inhibition of Akt reduced the T-bet:Eomes ratio and effectively increased the number of memory cells, especially of the effector memory phenotype. It is possible that treatment with A-443654 mitigated differentiation of CTLs into terminal effectors; instead, they survived and differentiated into effector memory cells. More potent Akt inhibition might be needed to increase the central memory CD8 T cells at the expense of terminal effector cells. Nevertheless, treatment with A-443654 augmented the number of effector memory cells that may play crucial roles in conferring effective immunity against mucosal pathogens and microbes like HIV (48).

The data presented in this paper suggests a model in which signals from the TCR and cytokine receptors converge on the Akt signaling pathway, and the cumulative signal strength determines the amplitude of Akt activation, which in turn governs the differentiation of effector CD8 T cells. This “signal strength” model supports the progressive/decreasing potential model of T cell differentiation (5). We propose that Akt activation at a certain threshold fosters development of effector functions (16) without impeding the differentiation of MPECs and their descendent memory CD8 T cells. However, sustained activation of Akt (e.g. in CD25HI cells) drives differentiation of CD8 T cells into terminal effectors at the expense of MPECs by paralyzing a multitude of cell survival mechanisms. Thus, Akt functions as a cellular rheostat controlling distinct facets of the program that governs differentiation of Ag-activated CD8 T cells into terminal effector cells or memory CD8 T cells. In summary, therapeutic modulation of the Akt signaling pathway may be exploited to enhance vaccine-induced protective immunity or treat T cell-dependent inflammatory pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Hotchkiss, Singer, and Murali-Krishna for generously providing the Akt, IL-7R, and P14 transgenic mice strains respectively. We also thank Dr. Giranda for kindly providing the Akt inhibitor.

This work was supported by PHS grants AI48785 and AI59804 to Dr. M. Suresh. Jeremy Sullivan was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (10POST4580038).

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors of this manuscript declare that they do not have any conflict of interest related to the findings presented in this document.

References

- 1.Teixeiro E, Daniels MA, Hamilton SE, Schrum AG, Bragado R, Jameson SC, Palmer E. Different T cell receptor signals determine CD8+ memory versus effector development. Science. 2009;323:502–505. doi: 10.1126/science.1163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haring JS, Badovinac VP, Harty JT. Inflaming the CD8+ T Cell Response. Immunity. 2006;25:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zehn D, Lee SY, Bevan MJ. Complete but curtailed T-cell response to very low-affinity antigen. Nature. 2009;458:211–214. doi: 10.1038/nature07657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jameson SC, Masopust D. Diversity in T cell memory: an embarrassment of riches. Immunity. 2009;31:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ. Heterogeneity and cell-fate decisions in effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation during viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar S, Kalia V, Haining WN, Konieczny BT, Subramaniam S, Ahmed R. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J Exp Med. 2008;205:625–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao RR, Li Q, Odunsi K, Shrikant PA. The mTOR Kinase Determines Effector versus Memory CD8+ T Cell Fate by Regulating the Expression of Transcription Factors T-bet and Eomesodermin. Immunity. 2010;32:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanjabi S, Mosaheb MM, Flavell RA. Opposing Effects of TGF-[beta] and IL-15 Cytokines Control the Number of Short-Lived Effector CD8+ T Cells. Immunity. 2009;31:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang JT, Palanivel VR, Kinjyo I, Schambach F, Intlekofer AM, Banerjee A, Longworth SA, Vinup KE, Mrass P, Oliaro J, Killeen N, Orange JS, Russell SM, Weninger W, Reiner SL. Asymmetric T lymphocyte division in the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Science. 2007;315:1687–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1139393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalia V, Sarkar S, Subramaniam S, Haining WN, Smith KA, Ahmed R. Prolonged interleukin-2Ralpha expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells favors terminal-effector differentiation in vivo. Immunity. 2010;32:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, Yu S, Zhao D-M, Harty JT, Badovinac VP, Xue H-H. Differentiation and Persistence of Memory CD8+ T Cells Depend on T Cell Factor 1. Immunity. 2010;33:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araki K, Turner AP, Shaffer VO, Gangappa S, Keller SA, Bachmann MF, Larsen CP, Ahmed R. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating Downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kane LP, Weiss A. The PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway and T cell activation: pleiotropic pathways downstream of PIP3. Immunological Reviews. 2003;192:7–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macintyre AN, Finlay D, Preston G, Sinclair LV, Waugh CM, Tamas P, Feijoo C, Okkenhaug K, Cantrell DA. Protein Kinase B Controls Transcriptional Programs that Direct Cytotoxic T Cell Fate but Is Dispensable for T Cell Metabolism. Immunity. 2011;34:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feau S, Schoenberger SP. From the Loading Dock to the Boardroom: A New Job for Akt Kinase. Immunity. 2011;34:141–143. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bommhardt U, Chang KC, Swanson PE, Wagner TH, Tinsley KW, Karl IE, Hotchkiss RS. Akt Decreases Lymphocyte Apoptosis and Improves Survival in Sepsis. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;172:7583–7591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Q, Erman B, Park J-H, Feigenbaum L, Singer A. IL-7 Receptor Signals Inhibit Expression of Transcription Factors TCF-1, LEF-1, and RORγt. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;200:797–803. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed R, Salmi A, Butler LD, Chiller JM, Oldstone MB. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J Exp Med. 1984;160:521–540. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitton JL, Southern PJ, Oldstone MB. Analyses of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to glycoprotein and nucleoprotein components of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology. 1988;162:321–327. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badovinac VP, Haring JS, Harty JT. Initial T Cell Receptor Transgenic Cell Precursor Frequency Dictates Critical Aspects of the CD8+ T Cell Response to Infection. Immunity. 2007;26:827–841. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M, Sourdive DJD, Zajac AJ, Miller JD, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting Antigen-Specific CD8 T Cells: A Reevaluation of Bystander Activation during Viral Infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo Y, Shoemaker AR, Liu X, Woods KW, Thomas SA, de Jong R, Han EK, Li T, Stoll VS, Powlas JA, Oleksijew A, Mitten MJ, Shi Y, Guan R, McGonigal TP, Klinghofer V, Johnson EF, Leverson JD, Bouska JJ, Mamo M, Smith RA, Gramling-Evans EE, Zinker BA, Mika AK, Nguyen PT, Oltersdorf T, Rosenberg SH, Li Q, Giranda VL. Potent and selective inhibitors of Akt kinases slow the progress of tumors in vivo. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2005;4:977–986. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pipkin ME, Sacks JA, Cruz-Guilloty F, Lichtenheld MG, Bevan MJ, Rao A. Interleukin-2 and inflammation induce distinct transcriptional programs that promote the differentiation of effector cytolytic T cells. Immunity. 32:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Na S-Y, Patra A, Scheuring Y, Marx A, Tolaini M, Kioussis D, Hemmings B, Hünig T, Bommhardt U. Constitutively Active Protein Kinase B Enhances Lck and Erk Activities and Influences Thymocyte Selection and Activation. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;171:1285–1296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lefrançois L, Obar JJ. Once a killer, always a killer: from cytotoxic T cell to memory cell. Immunological Reviews. 2010;235:206–218. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, Mullen AC, Gasink CR, Kaech SM, Miller JD, Gapin L, Ryan K, Russ AP, Lindsten T, Orange JS, Goldrath AW, Ahmed R, Reiner SL. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finlay D, Cantrell DA. Metabolism, migration and memory in cytotoxic T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;11:109–117. doi: 10.1038/nri2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutishauser RL, Martins GA, Kalachikov S, Chandele A, Parish IA, Meffre E, Jacob J, Calame K, Kaech SM. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 promotes CD8(+) T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity. 2009;31:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerdiles YM, Beisner DR, Tinoco R, Dejean AS, Castrillon DH, DePinho RA, Hedrick SM. Foxo1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7 and interleukin 7 receptor. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:176–184. doi: 10.1038/ni.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hand TW, Morre M, Kaech SM. Expression of IL-7 receptor alpha is necessary but not sufficient for the formation of memory CD8 T cells during viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11730–11735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705007104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeannet G, Boudousquie C, Gardiol N, Kang J, Huelsken J, Held W. Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:9777–9782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914127107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Hinrichs CS, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, Boni A, Cassard L, Garvin LM, Paulos CM, Muranski P, Restifo NP. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:808–813. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2010;35:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacob J, Baltimore D. Modelling T-cell memory by genetic marking of memory T cells in vivo. Nature. 1999;399:593–597. doi: 10.1038/21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bannard O, Kraman M, Fearon DT. Secondary replicative function of CD8+ T cells that had developed an effector phenotype. Science. 2009;323:505–509. doi: 10.1126/science.1166831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Opferman JT, Ober BT, Ashton-Rickardt PG. Linear differentiation of cytotoxic effectors into memory T lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:1745–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Araki K, Youngblood B, Ahmed R. The role of mTOR in memory CD8+ T-cell differentiation. Immunological Reviews. 2010;235:234–243. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juntilla MM, Koretzky GA. Critical roles of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in T cell development. Immunology Letters. 2008;116:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hand TW, Cui W, Jung YW, Sefik E, Joshi NS, Chandele A, Liu Y, Kaech SM. Differential effects of STAT5 and PI3K/AKT signaling on effector and memory CD8 T-cell survival. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:16601–16606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003457107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouyang W, Beckett O, Flavell RA, Li MO. An essential role of the Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 in control of T cell homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30:358–371. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tripathi P, Kurtulus S, Wojciechowski S, Sholl A, Hoebe K, Morris SC, Finkelman FD, Grimes HL, Hildeman DA. STAT5 Is Critical To Maintain Effector CD8+ T Cell Responses. J Immunol. 2010;185:2116–2124. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cruz-Guilloty F, Pipkin ME, Djuretic IM, Levanon D, Lotem J, Lichtenheld MG, Groner Y, Rao A. Runx3 and T-box proteins cooperate to establish the transcriptional program of effector CTLs. J Exp Med. 2009;206:51–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou X, Yu S, Zhao DM, Harty JT, Badovinac VP, Xue HH. Differentiation and persistence of memory CD8(+) T cells depend on T cell factor 1. Immunity. 33:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 33:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.