Abstract

The facile conjugation of three azido modified functionalities, namely a therapeutic drug (methotrexate), a targeting moiety (folic acid), and an imaging agent (fluorescein) with a G5 PAMAM dendrimer scaffold with cyclooctyne molecules at the surface through copper-free click chemistry is reported. Mono-, di-, and tri-functional PAMAM dendrimer conjugates can be obtained via combinatorial mixing of different azido modified functionalities simultaneously or sequentially with the dendrimer platform. Preliminary flow cytometry results indicate that the folic acid targeted nanoparticles are efficiently binding with KB cells.

Keywords: PAMAM dendrimer, copper-free click conjugation, drug delivery

For several decades, polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers have been used as a platform to deliver therapeutics and imaging agents, both in vitro1 and in vivo.2 A sequential synthetic strategy based on amide and ester chemistry is often used to conjugate small molecules, such as therapeutic drugs, targeting groups and imaging agents, to generate the functional forms of the dendrimer.3 While sufficient for small-scale needs, the extensive purification & characterization required between each small molecule addition, as well as batch-to-batch reproducibility issues, made it ill-suited for large-scale needs. Cu(I)-catalyzed alkyne azide 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (CuAAC), widely used for bioconjugation due to its high yields, tolerance toward functional groups, and lack of concurrent side-reactions, was initially an attractive alternative to our amide and ester conjugation chemistry.4 However, the copper catalyst proved difficult to remove from the dendrimers5 and the cytotoxicity6 associated with the residual copper prevented CuAAC from being a viable option. Several metal-free bioorthogonal labeling reactions such as strain-promoted cycloaddition of azides7, which relies on the unusually high ring strain associated with cyclooctyne to react rapidly and selectively with azide groups8, have since been developed.9

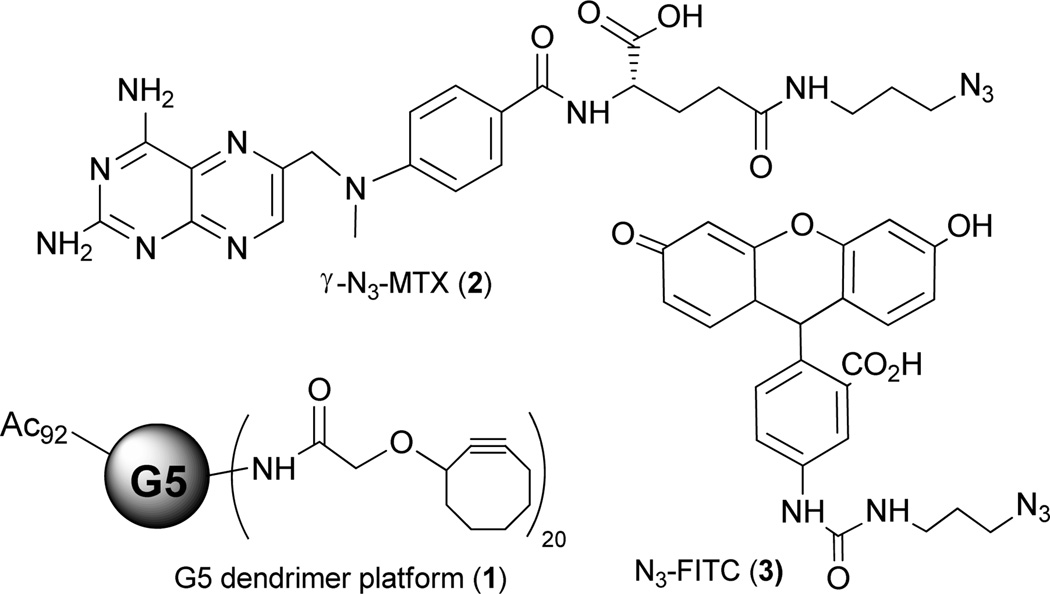

Recently, we synthesized a G5 PAMAM platform with cyclooctyne ligand on the surface for copper-free click conjugation with azido modified functionalities.10 Briefly, the G5 PAMAM dendrimer was first partially (70%) acetylated and then coupled with 20 cyclooctyne ligands through amide bonds. The remaining primary amine groups on the dendrimer surface were neutralized by acetylation. (Figure 1, compound 1) Variable equivalents (5, 10, and 18 equiv.) of γ-azido modified methotrexate (γ–N3-MTX) were reacted with the dendrimer platform efficiently with >90% of the modified drug conjugated. Here we report the facile conjugation of multiple functional groups with the PAMAM dendrimer platform via copper-free click chemistry. Three types of azido-modified functionalities, namely a therapeutic drug (γ–N3-MTX, 2), a targeting group (γ–N3-folic acid, 7), and an imaging agent (N3-FITC, 3) were reacted with the G5 dendrimer platform simultaneously or sequentially to achieve multifunctional nanodevices.

Figure 1.

Structures of PAMAM dendrimer platform, γ-azido modified MTX, and azido modified fluorescein

γ–N3-MTX (Figure 1, compound 2) was synthesized using our published method. Briefly, 4-amino-4-deoxy-N10-methylpteroic acid was first reacted with Glu-α-OtBu using BOP reagent to give α-OtBu-MTX. The γ carboxylic acid group was then coupled with 3-azido-propylamine in the presence of HATU. After exposure of the α carboxylic acid functional group using trifluoroacetic acid, γ–N3-MTX was obtained in excellent yield.10 Azido modified fluorescein (Figure 1, compound 3) was synthesized in a straightforward manner using fluorescein isothiocyanate and 3-azido-propylamine (see supplementary data).

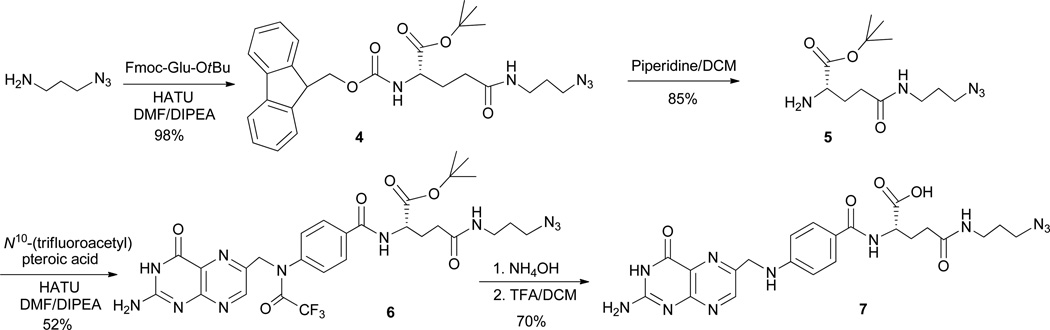

A number of cancer cell lines exhibit high levels of the cell surface folate receptor (FR) while its expression is highly restricted in most normal tissues. The degree of overexpression of the FR on human epithelial cancer cells ranges from 30-fold (ovarian carcinoma) up to 1400-fold (endometrial cancer). 4b Hence, the FR is a very attractive molecular target for receptor-based tumor imaging and therapy. 11 The folic acid structure offers two positions for bioconjugation, the α- and γ-carboxylic acid. Whether or not the binding affinity and in vivo pharmacological behavior is dependent on the site of conjugation is still debated in the literature.12 Here we synthesized a γ-azido modified folic acid (Scheme 1). Mindt et al synthesized a γ-azido modified folic acid starting from double-protected pteroic acid.13 Starting from commercially available N10-(trifluoroacetyl) mono-protected pteroic acid, we synthesized γ-azido folic acid (5) in 5 steps with good yield. Originally, we tried to use BocGluOMe as a precursor,13 but the final removal of α-methyl ester with NaOH yielded 8–15% racemization (data not shown). In order to avoid the basic conditions that were responsible for the racemization, we replaced BocGluOMe with FmocGluOtBu. Briefly, FmocGluOtBu was coupled with 3-azido-propylamine to obtain compound 4, followed by the exposure of amino group with piperidine to give compound 5. N10-(trifluoroacetyl) pteroic acid was then coupled with 5 to give a folic acid intermediate with α-tBu ester and N10-(trifluoroacetyl) protecting groups (6). The removal of these two groups sequentially with ammonium hydroxide and TFA gave compound 7. Compound 7 was obtained by precipitation with diethyl ether and collected by centrifugation (see supplementary data). We later found that the protection of the primary amino group at the pteridine ring was not necessary.

Scheme 1.

The synthesis of a γ-azido modified folic acid.

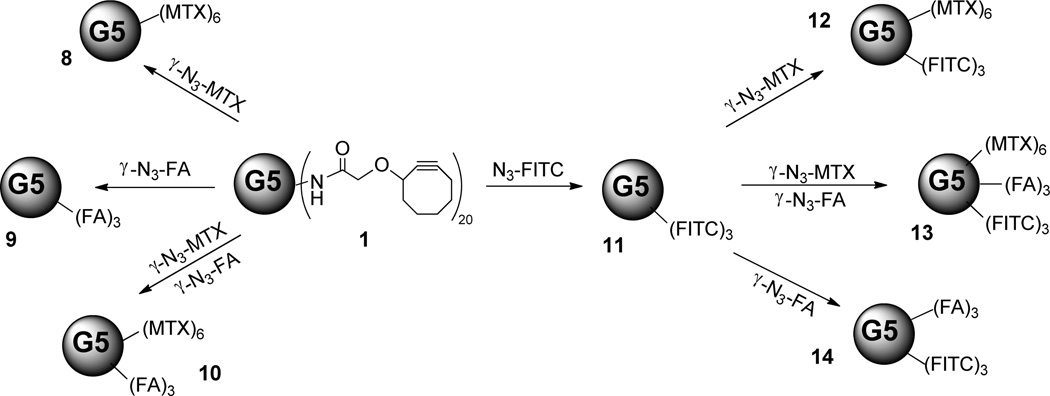

The copper-free click conjugation of the dendrimer platform with azido modified functionalities was then carried out (Scheme 2). Briefly, the methanol solution of G5 PAMAM dendrimer with cyclooctyne ligand molecules (1) was mixed simultaneously or sequentially with one, two or three of the previously mentioned targeting moiety (γ–N3-FA, 7), therapeutic drug (γ–N3-MTX, 2), and imaging agent (N3-FITC, 3). Because of the structural similarity of the azido modified folic acid and methotrexate, we assumed that they would have similar reactivity. Therefore, the di-functional conjugate was made by mixing these two compounds simultaneously with the platform. The conjugates containing the structurally dissimilar fluorescein were synthesized in a slightly different manner to ensure that the average number of fluoresceins per conjugate was identical, a critical requirement for the in vitro cell binding studies. In that case, we mixed the N3-FITC with the dendrimer platform and allowed the click reaction to go to completion. The reaction mixture was then separated into four equal aliquots; one aliquot was purified to give compound 11. Subsequent addition of γ–N3-FA, γ–N3-MTX, and both of these two compounds to three of the aliquots gave conjugates 12, 13, and 14, each containing the same average number of fluorescein molecules (Scheme 2). All of the click reactions were stirred for 24 hours at room temperature shielded from light. After removal of the organic solvent, the residues were dissolved in phosphate buffer saline (1×PBS buffer, pH=7.4) and purified by 10K centrifugal filters (PBS×3, DI water×6) and then lyophilized to give compounds 8–14 with good yields. More than 90% of the azido modified functionalities were conjugated through click reaction with the dendrimer platform.

Scheme 2.

The copper-free click conjugations of the dendrimer platform with azido modified functionalities. (Numbers of functionalities are rounded to the nearest integers.)

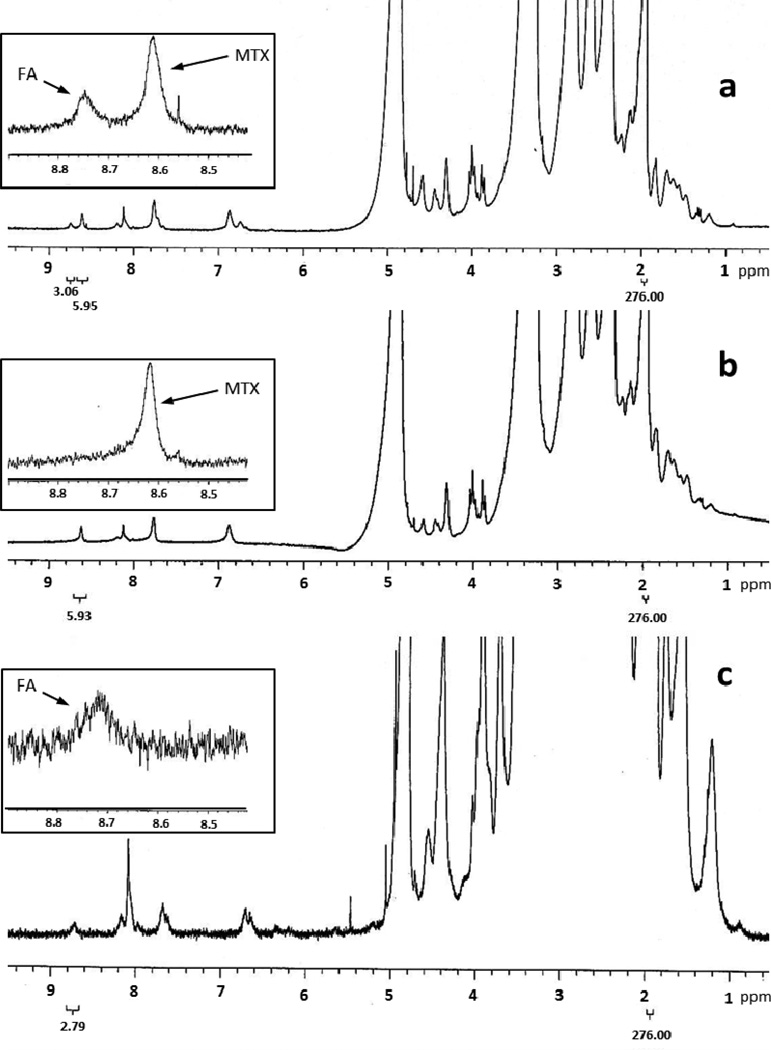

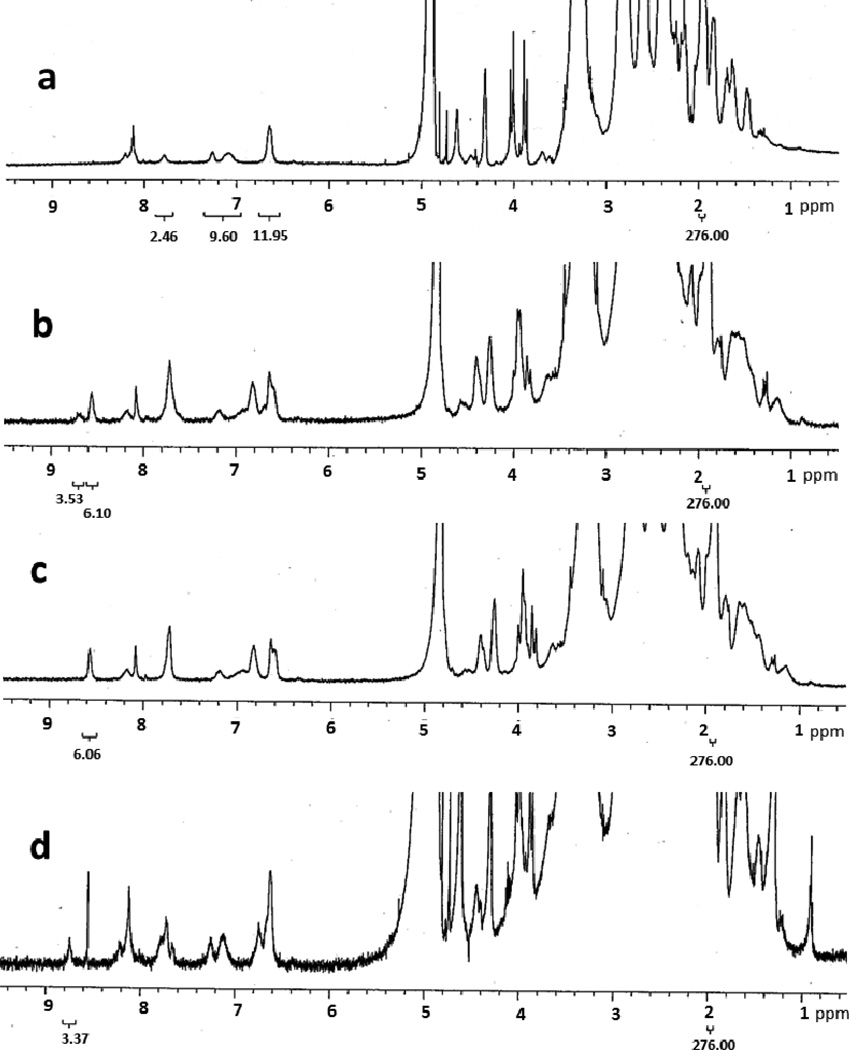

Using the integration of the acetamide proton of the dendrimer platform as an internal reference, the average number of each type of small molecule conjugated was determined using 1HNMR. The aromatic proton in the pteridine ring of MTX and folic acid had a chemical shift at 8.61ppm and 8.64ppm.10, 13 After the conjugation, the pteridine proton signal of folic acid shifted down field to 8.71–8.73ppm.13 By comparing the integration of these two peaks to the integration of the acetamide proton peak we determined the numbers of MTX and folic acid molecules conjugated to the dendrimer platform. The 1HNMR spectra of compounds 8, 9, and 10 are shown in figure 2. In these cases, the integrations of the internal reference peaks were set to 276 which represented 96 acetamide groups.10 The results indicated that the average numbers of MTX and folic acid in compound 10 were 5.95 and 3.06. Compound 8 had 5.93 MTX molecules and compound 9 had 2.79 folic acid molecules per dendrimer molecule (see inserts in Figure 2), respectively.

Figure 2.

1HNMR of compounds 10(a), 8(b), and 9(c). Inserts are the enlargements of the spectra (8.40–8.90ppm) showing the pteridine ring proton signals of folic acid (FA) and methotrexate (MTX).

The 1HNMR spectra of compounds 11–14 are shown in Figure 3. The number of fluorescein molecules conjugated was first calculated based on the relative proton integrations of the eight aromatic protons in the fluorescein structure, located between 6.40–7.81ppm, and the internal reference. The result indicated there were 3 dye molecules per dendrimer molecule averagely (Figure 3c). Because compounds 12, 13, and 14 were synthesized by subsequent additions of azido modified MTX and/or folic acid, the average number of fluorescein molecules per conjugate was identical. Using the same method described above, we determined the average numbers of MTX and folic acid molecules conjugated to the platform. Results indicated that there were 3.53 molecules of folic acid and 6.10 molecules of MTX in compound 13 (Figure 3b), 6.06 molecules of MTX in compound 12 (Figure 3c), and 3.37 molecules of folic acid in in compound 14 (Figure 3d), respectively.

Figure 3.

1HNMR of compounds 11(a), 13(b), 12(c) and 14(d).

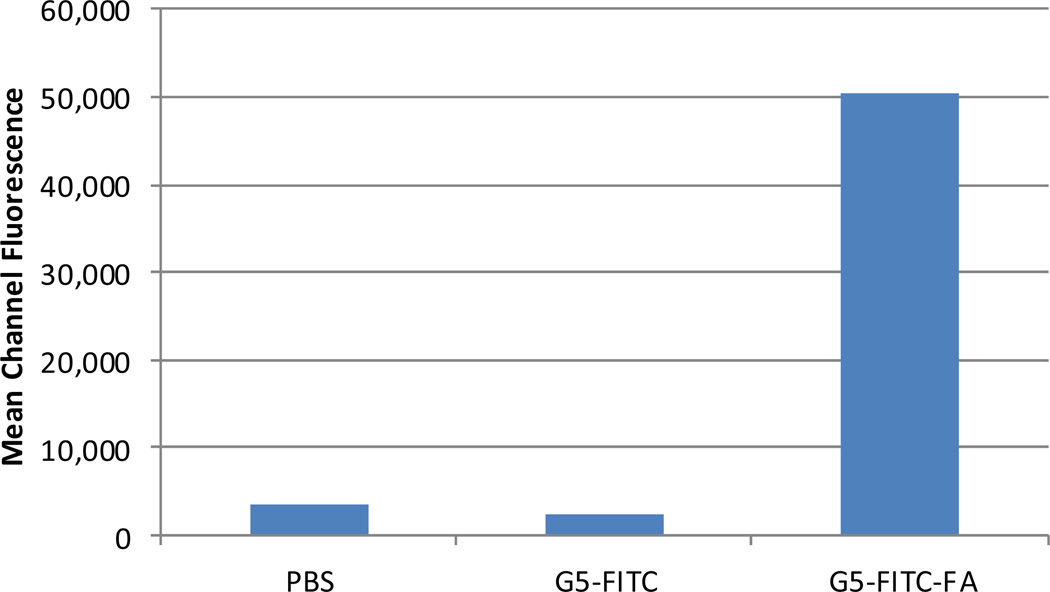

The KB human tumor cell line, which overexpresses the folate receptor14 was purchased from the American Type Tissue Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in vitro at 37°C, 5% CO2 in folate-deficient RPMI 1640 supplemented with penicillin(100 units/mL), streptomycin (100 µG/mL), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. The cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA solution, washed and resuspended in PBS. The cell suspension (106 cells in 0.1 mL) was incubated for 30 min on ice with 0.3 µM of targeted (G5-FITC-FA) or non-targeted (G5-FITC) conjugate. After incubation the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and re-suspended in PBS for analysis. Flow cytometry analysis was done using Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (BDBiosciences) and CFlow Plus software. Data were reported as the mean channel fluorescence of the cell population stained with 0.3 µM of G5-FITC-FA or G5-FITC. Flow cytometry results indicated that the targeted nanoparticle binds specifically to KB cells. The non-targeted nanoparticle did not bind to KB cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of targeted (G5-FITC-FA), non-targeted (G5-FITC), and unstained control (PBS).

In conclusion, we have successfully synthesized mono-, di-, and tri-functionalized G5 PAMAM dendrimer conjugates with copper-free click conjugation method. An azido modified targeting moiety, a therapeutic drug, and an imaging reagent were mixed with a G5 PAMAM dendrimer nanoplatform simultaneously or sequentially to give mono-, di-, and tri-functional conjugates. The reactions were very efficient and reproducible. Preliminary flow cytometry results indicate that the FA targeted nanoparticles are efficiently binding with KB cells. The in vitro toxicity studies of these materials toward different cancer cell lines are under investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under award 1 R01 CA119409.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:

References

- 1.Thomas TP, Majoros IJ, Kotlyar A, Kukowska-Latallo JF, Bielinska A, Myc A, Baker JR. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:3729. doi: 10.1021/jm040187v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myc A, Kukowska-Latallo J, Cao P, Swanson B, Battista J, Dunham T, Baker JR. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2010;21:186. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328334560f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Thomas TP, Shukla R, Kotlyar A, Liang B, Ye JY, Norris TB, Baker JR. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:603. doi: 10.1021/bm701185p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shukla R, Thomas TP, Peters J, Kotlyar A, Myc A, Baker JR. Chem. Commun. 2005:5739. doi: 10.1039/b507350b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Meldal M, Tornoe CW. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2952. doi: 10.1021/cr0783479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mullen DG, McNerny DQ, Desai A, Cheng X-m, DiMaggio SC, Kotlyar A, Zhong Y, Qin S, Kelly CV, Thomas TP, Majoros I, Orr BG, Baker JR, Jr, Holl MMB. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:679. doi: 10.1021/bc100360v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dijk M, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ, van Nostrum CF, Hennink WE. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:2001. doi: 10.1021/bc900087a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Link AJ, Vink MKS, Tirrell DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10598. doi: 10.1021/ja047629c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gierlich J, Burley GA, Gramlich PME, Hammond DM, Carell T. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3639. doi: 10.1021/ol0610946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sletten EM, Nakamura H, Jewett JC, Bertozzi CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11799. doi: 10.1021/ja105005t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ornelas C, Broichhagen J, Weck M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3923. doi: 10.1021/ja910581d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becer CR, Hoogenboom R, Schubert US. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:4900. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang BH, Desai A, Zong H, Tang SZ, Leroueil P, Baker JR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:1411. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Kukowska-Latallo JF, Candido KA, Cao ZY, Nigavekar SS, Majoros IJ, Thomas TP, Balogh LP, Khan MK, Baker JR. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5317. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Majoros IJ, Myc A, Thomas T, Mehta CB, Baker JR. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:572. doi: 10.1021/bm0506142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Ross TL, Honer M, Lam PYH, Mindt TL, Groehn V, Schibli R, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:2462. doi: 10.1021/bc800356r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leamon CP, DePrince RB, Hendren RWJ. Drug Targeting. 1999;7:157. doi: 10.3109/10611869909085499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ke CY, Mathias CJ, Green MA. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2003;30:811. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mindt TL, Muller C, Melis M, de Jong M, Schibli R. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2008;19:1689. doi: 10.1021/bc800183r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turek JJ, Leamon CP, Low PS. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106:423. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.