Abstract

Context

Evidence is mixed regarding the impact of advance directives on end-of-life expenditures and treatments.

Objective

To examine regional variation in the associations between treatment-limiting advance directive use, end-of-life (EOL) Medicare expenditures and use of palliative and intensive treatments.

Design, Setting, and Patients

Prospectively collected survey data from the Health and Retirement Study for 3,302 Medicare beneficiaries who died between 1998 and 2007 linked to Medicare claims and the National Death Index. Multivariable regression models examined associations between advance directives, EOL Medicare expenditures and treatments by level of Medicare spending in the decedent’s Hospital Referral Region (HRR).

Main Outcome Measures

Medicare expenditures, life-sustaining treatments, hospice care and in-hospital death over the last six months of life.

Results

Advance directives specifying limits in care were associated with lower spending in HRRs with high average levels of EOL expenditures (−$5,585 per decedent, 95% CI −$10903 to −$267), but there was no difference in spending in HRRs with low or medium average levels of EOL expenditures. Directives were associated with lower adjusted probabilities of in-hospital death in high- and medium-spending regions (−9.8%, 95% CI −16 – −3 in high-spending; −5.3%, 95% CI −10% to −0.4%). Advance directives were associated with higher adjusted probabilities of hospice use in high- and medium-spending regions (17%, 95% CI 11% − 23% in high-spending regions, 11%, 95% CI 6% to 16% in medium-spending), but not in low-spending regions.

Conclusions

Advance directives specifying limitations in end-of-life care were associated with significantly lower levels of Medicare spending, lower likelihood of in-hospital death, and higher utilization of hospice care in regions characterized by higher levels of EOL spending.

End-of-life healthcare is a frequent target for efforts to control Medicare spending. In 2006, care for patients in their last year of life accounted for more than one-quarter of Medicare spending.1 Marked geographic variation in Medicare end-of-life (EOL) spending is well-documented2 and this variation is believed to be driven by providers rather than differences in patients’ preferences for aggressiveness of EOL care.3 There is concern that this expensive care may have limited clinical effectiveness and may be contrary to what patients want; surveys report that many patients do not wish to receive aggressive EOL treatment, though these preferences are often undocumented.4,5 A national study by Barnato and colleagues found that 42% of white Medicare beneficiaries worried about receiving too much care at the end-of-life, while an equal proportion worried about receiving too little care.6

Patients can use advance directives to document their preferences for the use or avoidance of life-sustaining treatments (living wills) or to appoint a surrogate to make EOL treatment decisions if one is no longer competent to make those decisions (durable power of attorney for healthcare, DPOA). While advance directives have become more common in the past few decades, evidence is mixed on whether they impact Medicare expenditures and treatment at the end-of-life.7,8,9

It is sometimes overlooked that an advance directive can only influence care when the patient’s wishes are inconsistent with the care that would be provided absent an advance directive. The wide variation in EOL Medicare expenditures across geographic regions suggests that default levels of care also vary regionally. Advance directives specifying limits in EOL care may have their greatest impact in regions where the norms are to provide very high intensity EOL care. Given that there exist regions with consistently high levels of spending for EOL care that may be of limited benefit and contrary to patient preferences, we used nationally representative survey data from the Health and Retirement Study linked to respondents’ Medicare claims to examine the relationship of advance directives with the cost and aggressiveness of EOL care in geographic regions across the United States characterized by high, medium, and low average expenditures for EOL care.

Methods

Study Population

We analyzed survey and Medicare claims data for Health and Retirement Study (HRS) respondents who died between 1998 and 2007 at age 65 or older, or after qualifying for Medicare through disability or end-stage renal disease. The HRS is a large, nationally representative panel survey that conducts biennial interviews of older Americans.10 The HRS also conducts an interview with a proxy informant, typically next-of-kin, after the respondent’s death. During the post-mortem interview, informants are asked about the decedent’s EOL experience, including the nature and type of their advance directives. Oral informed consent was obtained from subjects and proxies in the original study. The institutional review board of the University of Michigan approved the study protocol.

As our primary interest is in EOL Medicare spending and utilization, we limited our analytic sample to patients continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare during the last six months of life. We used data on deaths through 2007, which were the most recent available data that have been linked to Medicare claims.

Advance Directives

We measured the presence and type of advance directive from interviews with respondents’ next-of-kin conducted after death. For living wills, informants were asked: “Did [FIRST NAME] provide written instructions about the treatment or care [she/he] wanted to receive during the final days of [her/his] life?” If respondents had a written advance directive in place, additional questions were asked about the type of written instructions. Our analysis included those who indicated living wills limiting the type of care provided and those requesting all care. These informant reports have been used to document advance directive status previously.4 For DPOAs, informants were asked: “Did [FIRST NAME] make any legal arrangements for a specific person or persons to make decisions about his care or medical treatment if he could not make those decisions himself?”

Medicare Claims

During biennial interviews, HRS respondents were asked to provide their Medicare number and consent to the release of their claims for research purposes. For each decedent, we calculated Medicare spending in the last 6 months of life across all care settings (inpatient, outpatient, carrier, durable medical, hospice, home health and skilled nursing). All spending measures were adjusted to 2007 dollars using the medical Consumer Price Index.

EOL hospital care is a major driver of end-of-life expense, and a setting where many aggressive procedures to sustain life are performed. We used MedPAR and hospice files to identify all hospitalizations and hospice use in the last 6 months of life. We used ICD-9-CM procedure codes to identify a set of life-sustaining interventions which have been previously used as measures of EOL treatment intensity (intubation and mechanical ventilation; tracheostomy; gastrostomy tube placement; hemodialysis; enteral and parenteral nutrition; and CPR).11 We examined any hospice use at the end-of-life as a measure of palliative care. We assessed comorbidities in the year prior to the last six months of life using Elixhauser’s method for inpatient data.12

Regional Intensity of End-of-Life Care

We used Hospital Referral Region (HRR) measures of average per-decedent Medicare spending in the last 6 months life reported by the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care averaged across 1999 – 2005.13 We characterized HRRs by quartiles of EOL spending averaged across the 7-year period. Decedent’s HRR intensity was determined by ZIP code of residence.

Statistical Analysis

We used generalized linear models (GLM) with a log link function and gamma distribution to fit skewed Medicare end-of-life expenditure data.14 Multivariable regression models assessed the relationships between HRR end-of-life treatment intensity, advance directives specifying limits in treatment, and Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life. We first estimated the regressions typically reported in the literature, which assume a constant relationship between advance directives and individual EOL resource utilization. We next allowed the relationship between treatment-limiting advance directives and spending to vary for patients in high-, medium- and low-spending HRRs by including interactions between treatment-limiting advance directives and HRR spending type. Regressions also controlled for sex, self-reported race (whether Black or other relative to White), 5-year age categories, whether the respondent was in the highest tertile of household wealth at their last interview, indicators for having less than a high school education and a high school degree (relative to at least some college), being widowed/single or separated/divorced (versus married), self-reported chronic conditions in the interview prior to the last six months of life, Elixhauser comorbidities calculated from hospitalizations in the 12-month period prior to last six months of life and a linear time trend. All regressions were estimated with robust standard errors.

We tested for differential effects of treatment-limiting advance directives across regions by calculating average marginal effects of advance directives in low-, medium- and high-spending HRRs and conducting nonlinear Wald tests15 of the equality of EOL spending on decedents with and without treatment-limiting advance directives within and across levels of HRR spending. Two-sided significance testing was used throughout, and a P value of .05 was considered statistically significant.

We estimated logistic regressions of life-sustaining treatments, in-hospital death, and hospice use among decedents hospitalized during the last 6 months of life controlling for the patient characteristics described above to test their relationship between treatment-limiting advance directives and regional spending.

Our sensitivity analyses included examining components of Medicare spending, estimating models for decedents with and without at least one EOL hospitalization separately, and analyses stratifying by cause of death using 15-cause recodes from the National Death Index. We used SAS v9.2 (Cary, NC) for data manipulation and Stata 11 MP (College Station, TX) for analyses.

Results

4,761 HRS decedents who died between 1998 and 2007 (82% of 5,810 decedents with post-mortem interviews) also had linked Medicare data. In order to accurately account for EOL utilization, we excluded 1,445 decedents with any managed care enrollment during the last six months of life and 14 decedents who reported military coverage and might receive care through Veterans Health Administration facilities.

Our cohort included 3,302 decedents. Their mean age at death was 82.8. 56% were female. 70% were hospitalized at least once in the last six months of life; 41% died at in a hospital. 61% of the sample had either a living will or written DPOA, 39% of the sample completed a written, treatment-limiting advance directive. Table 1 presents the characteristics of individuals with and without a treatment-limiting advance directive. Median Medicare spending in the last six months of life did not vary by treatment-limiting advance directive status. In unadjusted comparisons, those with treatment-limiting advance directives had lower rates of life-sustaining treatment (34% vs. 39%, p = 0.002), lower rates of in-hospital death (37% vs. 43%, p < 0.001) and higher rates of hospice use (40% vs. 26%, p < 0.001). Those with advance directives were more likely to be white, affluent and highly educated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Decedents by Treatment-Limiting Advance Directive Statusa

| Treatment-Limiting Advance Directive (n = 1,275) | No Limiting Advance Directive (n = 2,027) | P value for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| End-of-Life Utilization | |||

| Medicare EOL Spending, median (range) | $21,008 (0 to 380,200) | $21,614 (0, to 522,754) | 0.533 |

| Any EOL Hospitalization, No. (%) | 906 (71%) | 1,449 (73%) | 0.249 |

| # EOL Hospitalizations, median (range) | 1 (0 to 9) | 1 (0 to 10) | 0.177 |

| Any Life Sustaining Treatments, No. (%) | 434 (34%) | 791 (39%) | 0.002 |

| In-Hospital death, No. (%) | 468 (37%) | 881 (43%) | < 0.001 |

| Hospice Stay, No. (%) | 510 (40%) | 527 (26%) | < 0.001 |

| Decedent Characteristics | |||

| Female, No. (%) | 715 (56%) | 1,075 (53%) | 0.071 |

| Non-White, No. (%) | 64 (5%) | 446 (22%) | < 0.001 |

| Age, mean (sd), years | 84.0 (8.0) | 82.0 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

| Lived in Low-Spending Region, No. (%) | 204 (16%) | 243 (12%) | 0.004 |

| Lived in High-Spending Region, No. (%) | 351 (28%) | 650 (32%) | 0.006 |

| Durable Power of Attorney Only, No. (%) | - | 584 (29%) | - |

| Wealth Greater than $100,000, No. (%) | 638 (50%) | 649 (32%) | < 0.001 |

| Had Less than High School Education, No. (%) | 396 (31%) | 1,055 (52%) | < 0.001 |

| High School Graduate, No. (%) | 447 (35%) | 548 (27%) | < 0.001 |

Hospital referral regions classified using Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare national Medicare end-of-life spending data, 1999 – 2005, not HRS data. Low-spending HRRs averaged $8,787 (range 7,252 – 9,707), medium-spending $10,848 (range 10,242 – 12,404), high-spending $15,744 (range 12,446 – $29,797) (unadjusted for inflation).

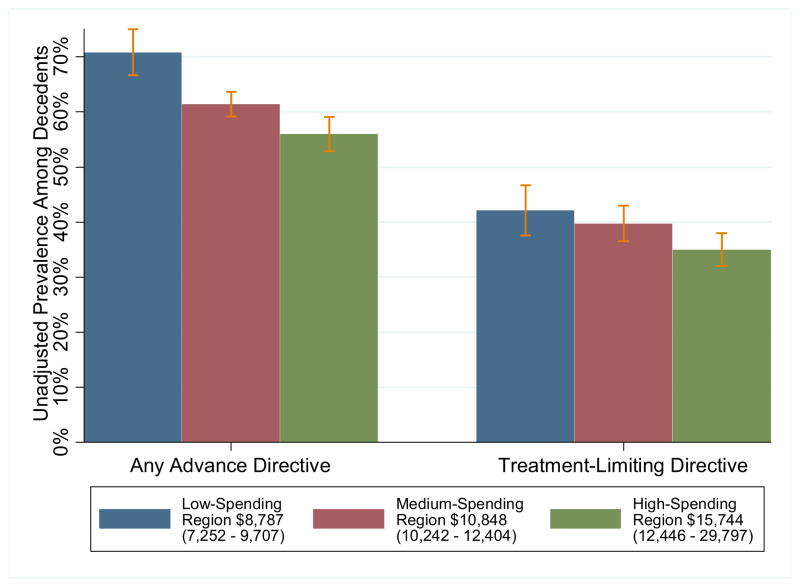

We compared EOL care of decedents living in HRRs in the lowest quartile of Medicare spending, (mean unadjusted spending $8,787; range 7252 – 9707), middle half ($10,848; 10242 – 12404), and highest quartile ($15,744; 12446 – 29797). There was substantial geographic diversity in the rates of advance directives among HRRs. Decedents residing in low-spending HRRs were more likely to have an advance directive (any advance directive, 47%; treatment-limiting advance directive 42%) than decedents in high-spending HRRs (any 39%, treatment-limiting 36%; both differences between low- and high-spending HRRs significant at p < 0.001) (Figure 1). After adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, decedents in high-spending HRRs continued to face lower odds of having a treatment-limiting advance directive (OR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.54 – 0.88). Though there was considerable variation in advance directive (Figure 1) and median end-of-life spending (Table 2) across HRRs, there was relatively little difference in cause of death or comorbidity prior to the end-of-life (Table 2). Regression-adjusted end-of-life spending was significantly lower for decedents in low-spending HRRs (predicted spending $21,741; 95% CI 19,668 – 23,816; difference $4,400, 95% CI 2,083 – 6,717) and higher for those in high-spending HRRs (predicted spending $37,841; 95% CI 34,855 – 40,107 difference $11,340, 95% CI 8,479 – 14,200) relative to those in medium-spending HRRs. Spending was considerably higher for non-white decedents (difference $6,561, 95% CI 3293 –9829)) and lower for decedents aged 90 and above relative to younger decedents (difference −$7,871, 95% CI −11,212 to −4,530). After adjusting for patient characteristics and HRR spending intensity, there was no difference in Medicare spending in the last 6 months of life for those with ($28,348, 95% CI 26,698 – 29,999) and without advance directives ($29,352, 95% CI 27,885 –30,819) (difference −$1,004, 95% CI −3,366 – 1,359) when using regressions that forced the association with advance directives to be the same for all regions.

Figure 1.

Geographic Variation in Advance Directivesa,b

aUnadjusted proportion of decedents with written advance directives across hospital referral regions in the United States. 3,302 Health and Retirement Study decedents dying between 1998 and 2007; 454 lived in low-spending regions, 1,847 in medium-spending regions, 1,001 in high-spending regions. Spending levels for Regions are based on average per-decedent Medicare spending in the last 6 months life reported by the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care for 1999 –2005, not on the particular decedents in the present study.31

bAny Advance Directive includes those with a Living Will or a Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare (DPOA). Treatment-Limiting Directive includes those with a Living Will that specifies “a desire to limit care in certain situations.”

Table 2.

Decedent Characteristics by Level of Regional End-of-Life Spendinga

| Low Spending Region n = 454 | Medium Spending Region n = 1,847 | High Spending Region n = 1,001 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare Spending (Median, Range) | |||

| Decedents with a Treatment -Limiting Advance Directive. | 14,153 (48.4 to 263,398) | 20,509 (0 to 166,349) | 25,290 (0 to 380,200) |

| Decedents with No Treatment-Limiting Advance Directive | 15,880 (0 to 128,920) | 20,628 (0 to 243,901) | 26,616 (0 to 522,754) |

| Cause of Death (No., (%)) | |||

| Cancer | 93 (21%) | 399(22%) | 185 (18%) |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 178 (40%) | 763 (41%) | 458 (46%) |

| Comorbidities Prior to EOL (No., (%)) | |||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 47 (11%) | 187 (10%) | 135 (13%) |

| Valvular Disease | 16 (3.5%) | 72 (3.9%) | 46 (4.6%) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 18 (3.9%) | 87 (4.7%) | 49 (4.9%) |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 78 (17%) | 388 (21%) | 222 (22%) |

| Hypertension, complicated | 19 (4.1%) | 95(5.1%) | 63(6.3%) |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 49 (11%) | 232(13%) | 122 (12%) |

| Diabetes, Uncomplicated | 31 (7%) | 193(10%) | 129 (13%) |

| Diabetes, Complicated | 8(1.7%) | 53(2.8%) | 29 (2.9%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 20 (4.4%) | 82(4.4%) | 65 (6.5%) |

| Renal failure | 13 (2.8%) | 88(4.8%) | 41 (4.1%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 9 (1.9%) | 34(1.8%) | 20(2%) |

| Solid tumor | 15 (3.3%) | 40(2.1%) | 28(2.8%) |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 44 (9.9%) | 155 (8.4%) | 91(9%) |

| Deficiency Anemia | 32 (7.2%) | 162 (8.7%) | 117 (12%) |

| Depression | 19 (4.2%) | 75 (4%) | 26(2.6%) |

Hospital referral regions classified using Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare national Medicare EOL spending, 1999 – 2005. Low-spending HRRs mean $8,787(range 7,252 – 9,707), medium-spending $10,848 (range 10,242 – 12,404), high-spending $15,744 (range 12,446 – $29,797) (nominal dollars).

However, there was important geographic heterogeneity in the relationship between advance directives and EOL spending (Table 3). In high spending regions, adjusted spending on patients with a treatment-limiting advance directive was $33,933 (95% CI 30,233 – 37,681), whereas adjusted spending for patients without an advance directive was $39,518 (95% CI 35,871 – 43,167; difference −$5585, (95% CI −10903 to −267). Having a treatment-limiting advance directive was not associated with differences in aggregate EOL spending for decedents in low and medium spending HRRs.

Table 3.

Regression-Adjusted Total Medicare Spending in Last 6 Months of Life:a

| Adjusted Association With Regional Spending Levels and Advanced Directive Useb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-Limiting Advance Directive Predicted Spending (95% CI) | No Limiting Directive Predicted Spending (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Low-Spending Regions | $21,96 (19228 to 24703) n = 203 |

$21,407 (18380 to 24434) n = 251 |

$559 (−3547 to 4665) | 0.79 |

| Medium-Spending Regions | $26,272 (24465 to 28078) n = 721 |

$26,002 (24489 to 27514) n = 1,126 |

$270 (−2235 to 2776) | 0.83 |

| High-Spending Regions | $33,933 (30233 to 37681) n = 351 |

$39,518 (35871 to 43167) n = 650 |

−$5,585 (−10903 to − 267) | 0.04 |

Health and Retirement Study linked to Medicare claims, 1998 – 2007. The Table reports average predicted spending based on average marginal effects from a general linear model of Medicare spending on the interaction between regional spending level and decedent advance directive status, sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities.

Hospital referral regions classified using Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare national Medicare end-of-life spending data, 1999 – 2005. Low-spending HRRs averaged $8,787(range 7,252 – 9,707), medium-spending $10,848 (range 10,242 – 12,404), high-spending $15,744 (range 12,446 – $29,797) (unadjusted for inflation).

Treatment-limiting advance directives were associated with site of death and palliative care for decedents in medium and high-spending regions (Table 4). Directives were associated with lower probabilities of in-hospital death in high- and medium-spending regions, but not in low spending regions. Thus, in high-spending regions, patients without an advance directive had a 47% adjusted probability of in-hospital death (95% CI 44% – 51%), whereas those with an advance directive had a 38% probability of in-hospital death (95% CI 29% – 41%; difference − 9.8%, 95% CI −16% to −3%). The equivalent results for in-hospital death for those in medium-spending regions were 42% without an advance directive (95% CI 39% – 45%) and 37% with an advance directive (95% CI 33% – 41%; difference −5.3%, 95% CI −10% to −0.4%). In high-spending regions, patients without a limiting advance directive had a 24% adjusted probability of hospice use (95% CI 21% – 28%), whereas those with a directive had an adjusted probability of hospice use of 41% (95% CI 36% – 46%; difference 17%, 95% CI 11% – 13%). Similar differences in hospice use occurred in medium-spending regions. There was no statistically significant relationship between treatment-limiting advance directive use and receipt of life-sustaining treatments during hospitalizations in the last six months of life, although the point estimates were in the same direction as for total EOL expenditures in high-spending HRRs; lower likelihood of utilization of life-sustaining treatments among those with treatment-limiting advance directives, p=0.11.

Table 4.

Predicted Probability of Treatments in the Last 6 Months of Life:a

| Adjusted Association With Regional Spending Levels and Advanced Directive Useb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-Limiting Advance Directive Probability (95% CI) | No Limiting Advance Directive Probability (95% CI) | Percentage Point Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Any Hospice, n = 3,302 | ||||

| Low-Spending Regions | 37% (31 to 44) n = 203 |

35% (30–41) n = 251 |

1.6% (−7 to 10) | 0.72 |

| Medium-Spending Regions | 38% (34 to 42) n = 721 |

27% (24–30) n = 1,126 |

11% (6 to 16) | p<0.001 |

| High-Spending Regions | 41% (36 to 46) n = 351 |

24% (21–28) n = 650 |

17% (11 to 23) | p<0.001 |

| In-Hospital Death, n = 3,302 | ||||

| Low-Spending Regions | 35% (29 to 41) n = 203 |

39% (29 to 41) n = 251 |

3.8% (−5.3 to 13) | 0.41 |

| Medium-Spending Regions | 37% (33 to 41) n = 721 |

42% (39 to 45) n = 1,126 |

−5.3% (−10 to −0.4) | 0.035 |

| High-Spending Regions | 38% (32 to 43) n = 351 |

47% (44 to 51) n = 650 |

−9.8% (−16 to −3) | 0.003 |

| Life-sustaining Treatments, n = 3,302 | ||||

| Low-Spending Regions | 29% (23 to 36) n = 203 |

28% (23 to 33) n = 251 |

1.4% (−7 to 10) | 0.74 |

| Medium-Spending Regions | 36% (33 to 40) n = 721 |

37% (34 to 40) n = 1,126 |

−0.9% (−6 to 4) | 0.72 |

| High-Spending Regions | 39% (34 to 44) n = 351 |

44% (40 to 48) n = 650 |

−5.2% (−12 to 1) | 0.11 |

Health and Retirement Study linked to Medicare claims, 1998 – 2007. The Table reports predicted probabilities using marginal effects from logit models predicting treatment status as a function of the interaction between regional spending level and decedent advance directive status, sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities.

Hospital referral regions classified using national Medicare end-of-life spending data, 1999 – 2005. Low-spending HRRs averaged $8,787(range 7,252 – 9,707), medium-spending $10,848 (range 10,242 –12,404), high-spending $15,744 (range 12,446 – $29,797) (unadjusted for inflation).

The differences in Medicare spending observed among those with advance directives in high-spending regions appears to be driven mainly by lower inpatient spending ($7509 lower, 95% CI $3,404 to $11,614 lower) slightly offset by higher hospice spending ($976 higher, 95% CI $294 to $1658 higher) (eTable 1). The differences in end-of-life spending across regions and advance directive status are concentrated among the 2,384 (72%) decedents experiencing at least one hospitalization in the last six months of life (eTable 2). There was no evidence of heterogeneity of the advanced directive effect in high-spending region across cause of death (p=0.44 for joint test of significance; eFigure 1).

3.8% of those with advance directives (1.5% of decedents overall) requested all care possible in their advance directive. There were too few such decedents in our study to reliably estimate the effects of such advance directives; these decedents are included in the no limiting directive group. On average, these decedents used $8,060 more care at the end-of-life (p= 0.02) than decedents with treatment-limiting directives.

Our results were consistent across numerous alternative specifications including an ordinary least squares regression, excluding all veterans as any VA care is unobserved in the Medicare claims, excluding disabled decedents who are under 65 but observed in the Medicare claims, excluding decedents with cancer as the cause of death, and excluding those who write advance directives in the last 6 months of life (eTable 3–6; eFigure 1).

Comment

Using linked personal interviews and Medicare claims for decedents in a large, nationally representative study, we found that advance directives specifying limits in treatment were more common in areas with lower levels of end-of-life spending. When patients in high-spending areas had advance directives limiting treatments, they averaged significantly lower EOL Medicare spending, were less likely to have an in-hospital death and, had significantly greater odds of hospice use than decedents without advance directives in these regions.

Our findings may reconcile prior, seemingly conflicting evidence that advance directives both reduce16,17 and do not affect18 end-of-life health care expenditures and use of life-sustaining treatments. We replicate the absence of a global relationship between advance directives and resource use, but extend the analysis to show that treatment-limiting advance directives are associated with lower Medicare expenditures for beneficiaries living in geographic regions characterized by aggressive end-of-life care. Most studies—including the landmark SUPPORT study in the 1980s19 —relied on samples from a small number of hospitals, precluding such geographic comparisons.20

These results suggest both the power and limitations of advance directives. One interpretation of these data is that advance directives are most effective when one prefers treatment that is different from the local norms. Thus, in high-intensity regions, more limited care requires an explicit statement. Treatment-limiting advance directives were associated with increased likelihood of palliative hospice care and lower rates of in-hospital deaths in high- and medium-spending regions, where patients were most likely to receive aggressive EOL care. This has important implications for patient quality of death and well-being of their family and friends. Previous research has found that next-of-kin report that the quality of death is higher for decedents who die at home21 or in hospice care22 relative to hospital and nursing home settings, that caregivers report worse overall physical and mental health following deaths characterized by use of aggressive EOL care,23 and surviving spouses of hospice decedents are less likely to die within 18 months of widowhood relative to widow/ers whose spouses did not use hospice.24

Interestingly, we found that while treatment-limiting advanced directives were associated with significantly lower total EOL Medicare expenditures in high-spending HRRs, the relationship between treatment-limiting advanced directives and the receipt of aggressive life-sustaining treatments (e.g., intubation and mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, and enteral and parenteral nutrition) was less strong. This may suggest that treatment-limiting advanced directives are associated with a quicker withdrawal of these aggressive and expensive interventions, even if the likelihood of initiating these treatments is less strongly affected. Given the significant consequences of these treatments for both patient/family well-being and healthcare costs, future research should be aimed at better understanding how advanced directives, DPOAs, and newer initiatives to improve “in-the-moment” EOL decision-making25 affect the initiation and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments.

Our results indicate a statistically and economically significant relationship between advance directives and regional practice patterns. The regional variations literature has asserted that significant savings to the Medicare population could be achieved if high-spending regions practiced more like low-spending regions.26,27 However, we note that patient preferences may also contribute to observed differences, possibly in a mutually reinforcing pattern. If an additional 6 percent of decedents in high-intensity regions had had treatment-limiting advance directives in place (matching preferences in low-spending regions), our estimates suggest that Medicare spending on the 790,061 beneficiaries dying in high-spending HRRs in 2006 would have been $265 million lower. We urgently need studies to examine the extent to which greater advance directive use in high-intensity regions would result in care that is more concordant with patient preferences and to understand the patient and provider characteristics that lead to higher rates of use in low-spending regions.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Since we used Medicare claims data to measure utilization, we were unable to include decedents not in fee-for-service Medicare. The associations and impact of advance directives may be different in other populations. However, Medicare-eligible adults account for more than 70 percent of deaths in the United States.28 We also lacked information about decedents who had not consented to the HRS-Medicare data linkage, though demographics of decedents in the linkage were similar to the full sample (eTable 8).

As our study was observational, we were unable to assess causal effects of advance directive use. We focused on the last six months of life, and were unable to address the question of how advance directives alter spending patterns over an individual’s life-course, nor the extent to which they influence the length of life. While limitations of the look-back approach to studying EOL intensity are well-known, this approach addresses the policy-relevant question of healthcare utilization just before death. 29 Our sensitivity analyses suggest that our results are not driven by heterogeneous patient characteristics. Further, we did not have patients’ own reports of preferences or copies of their advance directives. However, the post-mortem interviews are conducted with proxy informants, often widows or adult children, who are likely to know of advance directives if they were used; 78% were involved in decedents’ EOL decisions. Recent studies of older adults and their surrogate decision-makers support the reliability of this approach30,31

Advance directives are associated with important differences in care during the last six months of life for patients who live in areas of high medical expenditures, but not in other regions. This suggests that the clinical impact of advance directives is critically dependent on the context in which a patient receives care. Advance directives may be especially important for ensuring care consistent with patients’ preferences for those who prefer less aggressive care at the end of life, but are patients in systems characterized by high intensity of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (U01 AG09740, R01 AG030155, K08 HL091249) and Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, CTSA grant number UL1RR024986. The Health and Retirement Study is conducted at the Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

References

- 1.Riley GF, Lubitz JD. Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res. 2010 Apr;45(2):565–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wennberg JE, Cooper M. [Accessed January 3, 2011];The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org.

- 3.Barnato AEH, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, Gallagher PM, Skinner JS, Bynum JPW, Fisher ES. Are Regional Variations in End-of-Life Care Intensity Explained by Patient Preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Med Care. 2007 Jun;45(5):386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silviera MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr;362(13):1211–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, Sharp SM, Reding DJ, Knaus WA, et al. Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998 Oct;46(10):1242–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Jun;24(6):695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teno JM, Lynn J, Wenger NS, Phillips RS, Murphy DP, Connors AF, et al. Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: Effectiveness with the Patient Self-Determination ACT and the SUPPORT Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997 Apr;45(4):500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor JS, Heyland DK, Taylor SJ. How advance directives affect hospital resource use: Systematic review of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 1999 Oct;45:2408–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough: the failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30(5):S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CC, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Development and validation of hospital “end-of-life” treatment intensity measures. Med Care. 2009 Oct;47(10):1098–105. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181993191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998 Jan;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. [Accessed 20 September 2010];Data by Region. Available at http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/region/

- 14.Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized Modeling Approaches to Risk Adjustment of Skewed Outcomes Data. J Health Econ. 2005 May;25(3):465–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greene WH. Econometric Analysis. 6. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice–Hall; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar;169(5):480–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack J, Trice E, Balboni, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teno JM, Lynn J, Connors AF, Wenger N, Phillips RS, Alzola C, et al. The illusion of end-of-life resource savings with advance directives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997 Apr;45(4):513–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teno JM, Lynn J, Wenger NS, Phillips RS, Murphy DP, Connors AF, et al. Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: Effectiveness with the Patient Self-Determination ACT and the SUPPORT Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997 Apr;45(4):500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar;169(5):480–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A Measure of the Quality of Dying and Death: Initial Validation Using After-Death Interviews with Family Members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002 Jul;24(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, Nanda A, Wetle T. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of -life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:189–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack J, Trice E, Balboni, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. The health impact of health care on families: a matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Aug;57(3):465–75. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “Planning” in Advance Care Planning: Preparing for End-of-Life Decision Making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:288–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Vital Statistics Reports. Deaths: Final Data for 2007. 2010;58(19):1–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bach P, Schrag D, Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: a study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA. 2004;292(22):2765–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried TR, Redding CA, Robbins ML, O’Leary JR, Iannone L. Agreement Between Older Persons and Their Surrogate Decision Makers Regarding Participation in Advance Care Planning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1105–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McPherson CJ, Addington-Hall JM. Judging the quality of care at the end of life: can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med. 2003 Jan;56(1):95–109. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.