Abstract

Objective

To compare contraceptive efficacy, safety, and acceptability of C31G and nonoxynol-9 spermicidal gels.

Methods

We conducted a multicenter, randomized, double-masked, controlled trial to assess whether a gel containing the spermicide C31G was non-inferior to a commercially available product containing nonoxynol-9. Participants were healthy, sexually active females ages 18–40 years. Measured outcomes included pregnancy rates, continuation rates, adverse events, and acceptability. Sample size was calculated at a 2.5% significance level using a one-sided test, based on assumed 6-month pregnancy probability of 15% in the Conceptrol group. Sample size was sufficient to reject, with 80% power, the null hypothesis that pregnancy probability in the C31G arm would be more than 5% higher.

Results

Nine-hundred thirty-two women were randomized in the C31G group and 633 in the nonoxynol-9 group. For randomized subjects with at least one episode of coitus (modified intent-to-treat group), six-month pregnancy probabilities were 12.0% (95% confidence interval (CI) 9.3–14.7%) and 12.0% (95%CI 8.7–15.3%) for C31G and nonoxynol-9 respectively. Twelve-month pregnancy probabilities were 13.8% (95%CI 7.6–20%) for C31G and 19.8% (95%CI 10.9–28.7%) for nonoxynol-9. Two serious adverse events were deemed possibly related to study product, and neither occurred the C31G group. Three-fourths of users in either group reported that they liked their assigned study product. Approximately 40% of subjects discontinued prematurely for reasons other than pregnancy, with 11% lost to follow-up.

Conclusion

C31G demonstrated noninferior contraceptive efficacy compared to nonoxynol-9. Both products were safe and acceptable. C31G may provide another marketable option for women seeking spermicidal contraception.

Introduction

Spermicides are unique among contraceptive options. They are coitally dependent, but are not dependent on a male partner’s cooperation. Their low cost, availability, and ease of use may be desirable for women who have intercourse infrequently and want to avoid hormonal methods. Currently, spermicides are among the least commonly used methods of contraception in the United States, (1) yet there is a potentially high level of demand. (2)

All currently available spermicides contain the active ingredient nonoxynol-9 in a carrier, such as a gel, foam, or film. Nonoxynol-9 is a surfactant that immobilizes or kills sperm by destroying the sperm cell membrane. Because this action is not specific to sperm, it was hoped that nonoxynol-9 use would reduce the risk of sexually-transmitted infection. (3) However, more recent clinical trial results show that it can cause genital irritation (4), and may increase likelihood of HIV transmission in very frequent users. (5) Thus, the development of alternative spermicides has become a research priority.

C31G is a spermicidal mixture of two surfactants. Studies indicate that repeated use is safe, with less cervicovaginal toxicity than nonoxynol-9 (6), and similar in vitro activity. (7) Phase 1 studies of C31G indicated that a 1.0% concentration was optimal. (8) C31G effectively prevents sperm from penetrating mid-cycle mucus. (9) A male tolerance study showed that male partners of women using C31G did not suffer penile irritation from the product. (10) Taken together, these studies indicate that C31G is well-tolerated, safe, and effective.

We conducted a multicenter, randomized, double-masked trial of C31G spermicidal gel and a commercially available nonoxynol-9 spermicide (Conceptrol®, Ortho, Raritan, NJ) to compare contraceptive efficacy, acceptability, and safety. The primary objective was to estimate whether the contraceptive efficacy of C31G is non-inferior to that of nonoxynol-9. We hypothesized that the contraceptive efficacy of C31G would be non-inferior. Outcomes included pregnancy rates, adverse events, continuation rates, and acceptability.

Methods

This study was designed as a Phase III randomized, double-masked, non-inferiority trial to evaluate the contraceptive efficacy of C31G over six months of use (6 cycles and 183 days) compared to a commercially available, nonoxynol-9-based spermicidal gel. Participants also had the option to participate in an extension study for a total treatment period of 12 cycles or 365 days. The primary study outcome was contraceptive efficacy. Secondary outcomes included acceptability and safety. Safety assessments included incidence of urinary tract infections (UTI), bacterial vaginosis (BV), yeast infections, gonorrhea, and Chlamydia, and occurrence of adverse events (AE) and serious adverse events (SAE). The definition of an adverse event was any symptom, illness, or experience that developed or worsened in intensity after randomization. An SAE was defined according to FDA regulations as an event resulting in death, a life-threatening condition, hospitalization, or persistent or significant disability or incapacity. Congenital anomalies were also considered SAEs.

Participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study was conducted at 14 sites of the United States National Institute of Health (NIH) Eunice Shriver Kennedy National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Contraceptive Clinical Trials Network (CCTN) between 2004 and 2008. The protocol was initiated after obtaining approval from the institutional review board of each center, the data-coordinating center, and the NIH. Eligibility requirements included being a healthy, sexually active female, 18–40 years old, at risk for pregnancy and desiring contraception, having 24–35 day menstrual cycles, and being at low risk for HIV or other sexually transmitted infection. “Low risk” was defined as having a single male sexual partner for at least 4 months before study enrollment who was also at low risk for sexually transmitted infections. Study participants were asked to engage in at least 4 acts of vaginal sexual intercourse per month, use the study product as the primary method of contraception, and keep a diary of coital activity, product use, use of other vaginal products, and adverse events. Exclusion criteria included: allergy or sensitivity to either study product, 3 or more urinary tract infections (UTI) in the previous year, history of infertility, contraindication to pregnancy, use of shared drug injection needles in the previous 12 months, recent diagnosis (<3 months) or frequent outbreaks (>3/year) of herpes simplex virus (HSV), STI diagnosis within 6 months prior to enrollment, HIV infection, or abnormal cervical cytology confirmed by colposcopy within the previous 12 months.

Randomization, sample size, and product assignment

The two study drugs were C31G gel in a 1% concentration, and Conceptrol® gel, containing nonoxynol-9 in a 4% concentration. Randomization was performed in a 3:2 ratio of C31G to nonoxynol-9 (block size of 10) to obtain more information about adverse effects and acceptability in the C31G group. Test drugs were provided in single-use, pre-filled applicators with identical overwraps. Study drug was packaged at a central site according to the randomization schema in sequentially numbered opaque boxes. Interventions were assigned by opening the next sequentially numbered box of study supplies. Allocation concealment was assured by identical overwrapping of both products.

We performed a non-inferiority sample size calculation using nQuery Advisor® Release 4.0 with binomial distribution assumption. (11) We estimated that the 6-month cumulative probability of pregnancy using Kaplan-Meier methods would be 15% in women using nonoxynol-9 as their primary contraceptive for 6 months. At the 2.5% level of significance (one-sided), a sample size of 1002 women in the C31G treatment arm and 668 women in the nonoxynol-9 treatment arm was sufficient to reject, with 80% statistical power, the null hypothesis that the 6-month cumulative pregnancy probability in the C31G treatment arm is more than 5 percentage points greater than that in the Nonoxynol-9 Vaginal Gel treatment arm.

Once eligibility was confirmed, each participant returned for an admission visit, and was. randomly assigned to receive either the C31G or nonoxynol-9 gel formulation. Each participant received a study kit labeled with a randomized identification number, which contained a supply of single-use, pre-filled applicators sufficient to last until her next scheduled study visit. Study products had similar appearance, texture, and smell. Each subject also received a high-sensitivity urine pregnancy test, with instructions to perform the test two weeks after the admission visit and report the results to the study center.

Follow-up visits

Participants were scheduled for additional study visits after cycles 1, 3, and 6 of product use, and after cycle 12 for those participants in the study extension. At each visit, a gynecologic examination was performed, including wet mount and assessment for BV. Cervical cancer screening was also performed after cycles 6 and 12. Urine was collected for pregnancy test (all visits) and dipstick analysis (cycles 1, 3, and 9), and urine culture (cycle 6 and 12). Coital diaries and compliance with product use were reviewed, and an acceptability questionnaire was completed at cycles 1, 6, and 12.

Statistical analysis and outcome measures

Four analysis populations were defined for the final statistical analysis:

The intent-to-treat population (ITT) included all women randomized into the study.

The all-treated population (AT), defined as ITT subjects who applied study drug at least once, was used to determine safety and adverse event results.

Modified intent-to-treat population (MITT) consisted of ITT subjects whose diaries indicated they had at least one episode of coitus while using the assigned study product, and for whom there was at least one report of pregnancy status.

The efficacy-evaluable subset of the MITT population included only those subjects whose diaries indicated correct and consistent use (CC) of assigned study product for at least one menstrual cycle. Perfect-use estimates were calculated from this population.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the cumulative probability of pregnancy at 6 months (183 days), as determined from the MITT population. We defined non-inferiority as a pregnancy probability in the C31G group no more than 5 percent higher than in the nonoxynol-9 group. The Kaplan-Meier (KM) method was used to estimate the 6-month cumulative pregnancy probability of women in the MITT population for each treatment group. Pregnancies were excluded if they occurred prior to randomization or after discontinuation of study method. The Peto method(12) for calculating standard error, which focuses on the observed number of events in the experimental group, was used to construct 95% confidence intervals. This method was used to avoid underestimation of the standard error. Use of emergency contraception (EC) was allowed in this study. The effects of EC use on the CC pregnancy probability estimate were accounted for by subtracting the length of the cycle in which EC was used from the total length in study (days) for non-pregnant subjects, and for pregnant subjects if pregnancy did not occur in the cycle where EC was used. Any pregnancies that occurred in an incorrect-use cycle were excluded from the CC analyses. A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test was used to analyze EC use, and site was included in the model to account for center-to-center variation.

Secondary efficacy and effectiveness endpoints included 6-month correct and consistent use pregnancy probabilities, 12-month pregnancy probabilities, and 6-month Pearl rates. Correct and consistent 6- and 12-month pregnancy probabilities were calculated from the CC population using the KM method, while 6-month Pearl rates with confidence intervals (13, 14) were calculated from the MITT population.

Safety outcomes were determined for the AT population. Data were collected from all participants regarding adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs). To be recorded as an AE or SAE, an event had to begin or worsen between randomization and 14 days following last use of study product. Categorical methods were used to evaluate incidence of genitourinary infections, including UTI, BV, vaginal yeast infections, and STIs. For categorical data, either CMH test or Fisher's exact test was used. Acceptability of both products was compared using responses to a 3-item questionnaire.

Results

Participant characteristics

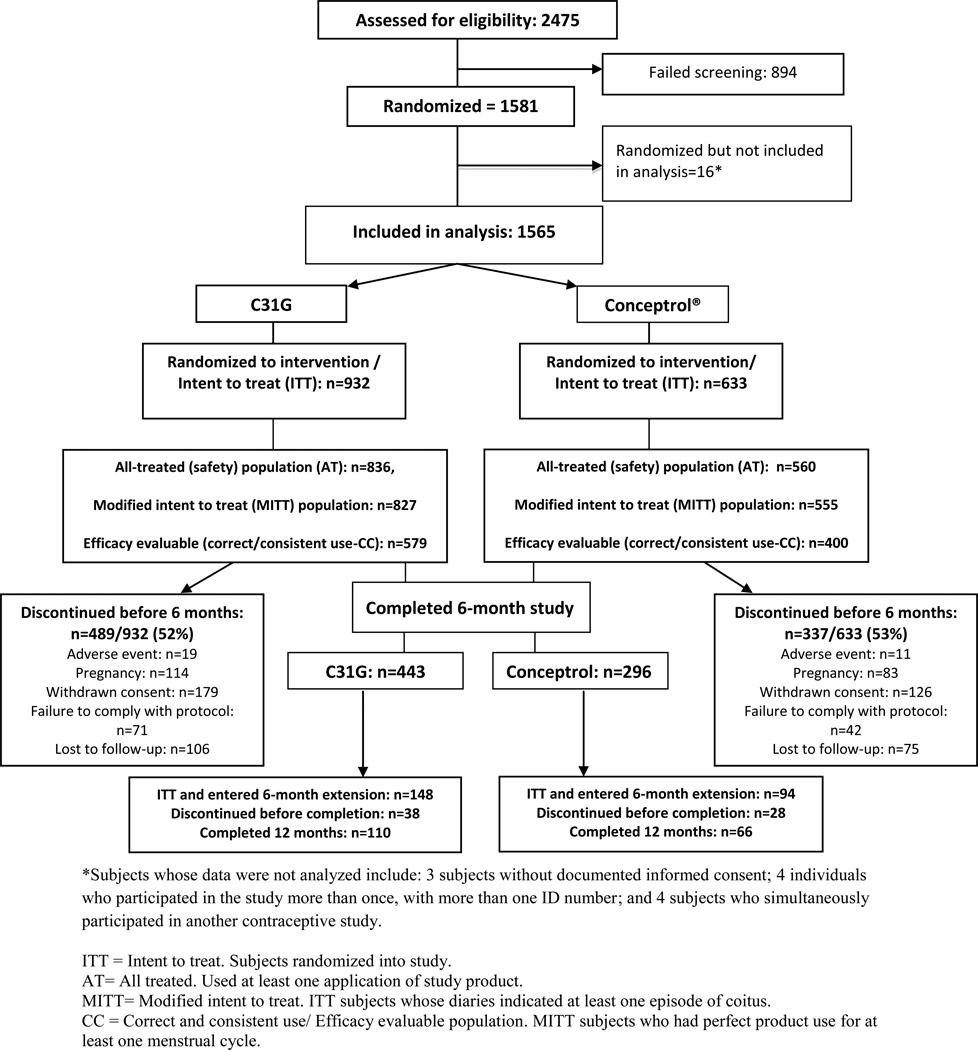

Enrollment, allocation, and follow-up numbers for participants are shown in Figure 1. Participants were primarily young, unmarried, non-Hispanic white women with at least some college education, who lived with their partners. (Table 1) Contraceptives most commonly used in the 6 months prior to enrollment included condoms (reported by 75% of participants), withdrawal (49%), and the rhythm method (14%). Only 17% had used hormonal contraception in the 6 months prior to enrollment, while 13% had used a spermicide within that time period. Over half (55%) had never used spermicide before this study.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic* | C31G (N=932) | Conceptrol (N=633) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, in years (Mean ± SD) | 28.1±5.6 | 28.3±5.9 | |

| Body mass index, kg/M2 (Mean ± SD) | 28.6±7.4 | 28.5±7.5 | |

| Gravidity (Mean ± SD) | 1.8±1.9 | 1.9±1.9 | |

| Parity (Mean ± SD, for those with prior pregnancy) | |||

| Term deliveries | 1.4±1.3 | 1.4±1.3 | |

| Preterm deliveries | 0.1±0.4 | 0.1±0.4 | |

| Spontaneous abortion | 0.4±0.8 | 0.4±0.7 | |

| Induced abortion | 0.7±1.0 | 0.7±0.9 | |

| Race (%) | |||

| Asian | 4 | 3 | |

| African-American | 29 | 31 | |

| Native American/Alaskan/Pacific Islander | 1 | 1 | |

| White/Caucasian | 50 | 53 | |

| Other | 15 | 12 | |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic/Latina (%) | 20 | 19 | |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Never married | 57 | 57 | |

| Married | 34 | 32 | |

| Separated | 2 | 2 | |

| Divorced | 7 | 9 | |

| Widowed | <1 | <1 | |

| Living arrangement (%) | |||

| Living with partner | 69 | 71 | |

| Not living with partner | 31 | 29 | |

| Education (%) | |||

| <12 years | 5 | 5 | |

| High school graduate | 14 | 18 | |

| Some college | 46 | 45 | |

| College graduate | 27 | 25 | |

| Masters/doctorate level | 8 | 7 | |

| Household income (%) | |||

| <10,000 | 16 | 21 | |

| 10,000 – 29,999 | 32 | 28 | |

| 30,000 – 49,999 | 27 | 27 | |

| 50,000 or more | 24 | 24 | |

| Alcohol use (%) | |||

| Never | 21 | 22 | |

| Less than once/month | 30 | 30 | |

| At least once/month | 29 | 28 | |

| At least once/week | 19 | 19 | |

| At least once/day | 1 | 2 | |

| Smoking (%) | |||

| Current | 20 | 25 | |

| Former | 21 | 20 | |

| Never | 59 | 55 | |

Values expressed as percentages except as otherwise noted.

All participants in the AT population reported at least one coital act during the study. The study product was used according to protocol (i.e., it was the only method used and was used correctly) for 76% of reported coital acts among the C31G group and 78% of coital acts among the Conceptrol® group (p=0.23). The study method was used with another method, used incorrectly, or not used at all in 3%, 5%, and 16% of coital acts, respectively, without any difference in the percentages for both treatment groups. An equal percentage of women in each group reported at least one departure from study instructions (43.9% in C31G group vs. 43.0% in Conceptrol® group). Slightly more than half of subjects in each group discontinued prior to study completion (Figure 1). Reasons for discontinuation are summarized in Figure 1. A large number of women in both groups withdrew consent, most commonly because of dissatisfaction with the study product (3.3% of C31G and 4.6% of Conceptrol® users), moving (1.9% of C31G and 2.5% of Conceptrol® users), and “other” reasons (11.7% of C31G and 11.8% of Conceptrol® users). None of these reasons was statistically different between groups. Older age (Odds Ratio (OR) 1.29, 95%CI 1.19 – 1.41, for every 5 years over age 18), and being married (OR 1.44, 95%CI 1.17–1.78) were significantly associated with study completion. Treatment group had no effect on the likelihood of study completion.

Contraceptive efficacy

For all participants, the mean, ± standard deviation (SD), number of days that study product was used was 50.3 ±37.32 days in the C31G group and 49.4±34.9 days in the Conceptrol® group. For those in the 6-month study, mean number of days of use was 40.3±27.1 days for C31G and 39.9±25.5 days for Conceptrol®, and in the 12 month extension study, the mean was 96.9±42.1 days for C31G and 96.9±36.5 days for Conceptrol®.

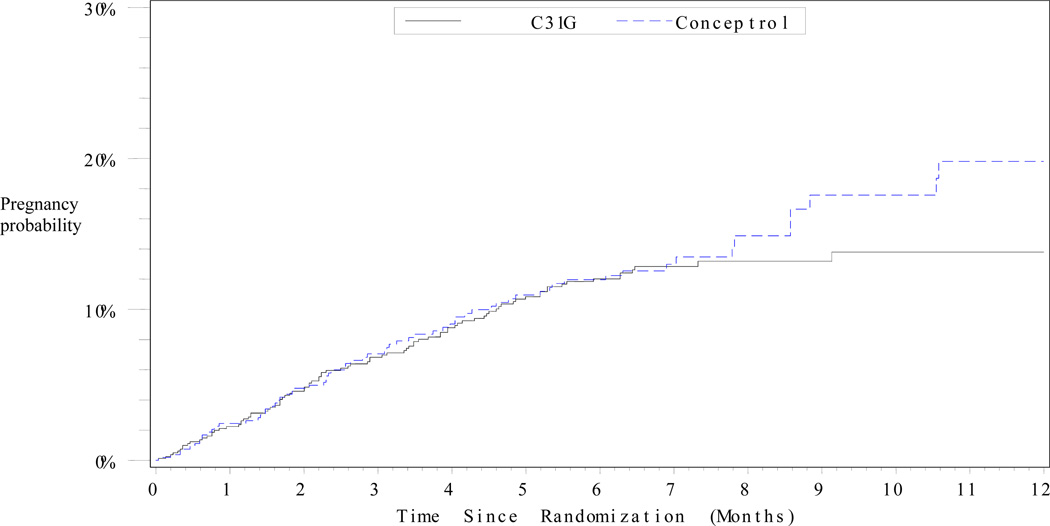

Table 2 and Figure 2 show the 6-month and 12-month pregnancy probabilities for both products. Pregnancy probabilities for both the MITT and CC populations demonstrate noninferiority of C31G compared to Conceptrol®. Pearl index pregnancy rates (MITT) were 26.0 for C31G and 26.1 for Conceptrol®, difference −0.1 (95% CI −8.9 – 8.7), based on 3925 months of pregnancy risk exposure for C31G and 2622 months for Conceptrol®. Analyses of pregnancy probabilities in the CC population were based on 2346 months in the C31G group and 1585 in the Conceptrol® group. There were no significant differences in pregnancy outcomes between groups. Within the MITT population, EC was used by 8.2% of women and 1.4% of cycles in the C31G group, and 5.4% of women and 0.9% of cycles in the Conceptrol® group (p=0.04).

Table 2.

Pregnancy probabilities for participants in both groups

| C31G (N=932) | Conceptrol (N=633) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | # pregnancies |

Pregnancy probability (%) |

95% CI | # pregnancies |

Pregnancy probability (%) |

95% CI | Diff | 95% CI |

| 6-month | ||||||||

| ITT | 88 | 11.4 | 8.8 – 14.1 | 60 | 11.6 | 8.4 – 14.9 | −0.2 | −4.4 – 3.9 |

| MITT | 85 | 12.0 | 9.3 – 14.7 | 57 | 12.0 | 8.7 – 15.3 | 0.0 | −4.3– 4.3 |

| CC | 17 | 4.8 | 1.6 – 7.9 | 12 | 4.5 | 0.7 – 8.3 | 0.3 | −4.7 – 5.2 |

| 12-month | ||||||||

| MITT | 91 | 13.8 | 7.6 – 20 | 68 | 19.8 | 10.9 – 28.7 | −6.0 | −16.9 – 4.9 |

| CC | 17 | 5.5 | 0.0 – 16.1 | 13 | 6.6 | 0.0 – 20.1 | −1.0 | −18.2 – 16.2 |

ITT = Intent-to-treat; MITT= Modified intent-to-treat; CC= Correct and consistent use (efficacy-evaluable)

Figure 2.

Cumulative probability of pregnancy over time among users of C31G and Conceptrol® (Kaplan-Meier method) in the modified intent-to-treat (MITT) group.

The MITT group included randomized subjects reporting at least one act of coitus.

Secondary outcomes: Safety and acceptability

Results of analyses of selected secondary outcomes are summarized in Table 3. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the frequencies of UTI, BV, or vaginal yeast infections. Rates of genitourinary discomfort were also similar, reported by about one-fifth of subjects in each group. There were no significant changes in Pap testing or wet mount findings from baseline to study exit with use of either product. Further, there were no significant differences between groups in these outcomes for the extension period, Cycle 6 through Cycle 12, of product use.

Table 3.

Percentage of participants who experienced selected secondary (safety and acceptability) outcomes (Ns based on all-treated (AT) population)

| Outcome ** | C31G (N=836) | Conceptrol (N=560) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection (%)+ | ||||

| Symptomatic UTI | 3 | 4 | 0.19 | |

| Any UTI | 8 | 8 | 0.55 | |

| BV (based on Amsel’s criteria) | 15 | 15 | 0.78 | |

| Yeast | 10 | 11 | 0.97 | |

| Gonorrhea/Chlamydia | 1 | 1 | ||

| Genitourinary discomfort (%)* | ||||

| Any | 21 | 19 | 0.46 | |

| Irritation | 7 | 6 | ||

| Itching | 8 | 8 | ||

| Burning | 6 | 5 | ||

| Difficulty urinating | 4 | 3 | ||

| Partner discomfort (%)* | 7 | 5 | 0.08 | |

| Acceptability (%) ¥ | ||||

| Liked (strongly/somewhat) | 74 | 75 | 0.51 | |

| Neutral | 15 | 15 | ||

| Disliked (strongly/somewhat) | 11 | 10 | ||

| Would use again (definitely/probably) | 77 | 78 | 0.32 | |

Outcomes were those reported at Cycle 6 visit, or exit visit if the subject discontinued early

Diagnosis based on urine culture, wet mount, or nucleic acid amplitude test (NAAT), as appropriate.

Reported response to the questions, “Since the last visit, did the subject have any genitourinary discomfort?”, and “Since the last visit, did the subject’s partner have any discomfort?”

Based on response to acceptability questionnaire

The proportion of subjects who experienced an adverse event considered possibly, probably, or definitely related to study contraceptive was significantly different between groups (35% of C31G subjects, 41% of Conceptrol® subjects, p=0.02). Related AEs reported by at least 2% of subjects are listed in Table 4. Percentage of subjects with a serious adverse event (SAE) exclusive of congenital anomaly was low in both groups (10 (1.2%) in C31G vs. 12(2.1%) in Conceptrol® groups, p=0.19). (Table 5) None of the SAEs in the C31G group were deemed related to the drug; of the SAEs listed for the Conceptrol® group, one case of hypersensitivity to the product and one case of pelvic inflammatory disease were respectively reported as definitely and probably related to product use.

Table 4.

Percentage of subjects experiencing an adverse event deemed possibly, probably, or definitely related to treatment (based on ATD population)

| Event | C31G (N=836) | Conceptrol (N=560) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women who experienced any AE related to study drug (%)(possible-probable-definite) | 35 | 41 | 0.023 |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 10 | 11 | |

| Fungal vaginitis | 10 | 11 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 8 | 10 | |

| Genital pruritus | 3 | 6 | |

| Menstrual irregularities | 5 | 4 | |

| Product discontinuation due to AE | 2 | 2 |

Events listed are those reported by at least 2% of subjects in each group, and could have occurred at any time during study participation.

Table 5.

List of serious adverse events (SAE) exclusive of congenital anomalies

| C31G (N=10; 1.2%) | Conceptrol® (N=12; 2.1%) |

|---|---|

| Anemia Crohn’s disease Food poisoning Viral gastroenteritis Cholelithiasis Joint dislocation Ruptured ovarian cyst Ectopic pregnancy Acute stress disorder Stress incontinence Menorrhagia |

Cardiac palpitations Diabetic ketoacidosis E. coli gastroenteritis Gastrointestinal pain Nausea Bile duct stone Hypersensitivity to product Pelvic inflammatory disease Laceration (unspecified) Hypoglycemia Dermoid cyst Viral meningitis Depression Kidney infection Infection (unspecified) |

N refers to number of subjects in each group with SAEs; some subjects reported more than one SAE.

Each of the specific SAEs listed was reported by one and only one participant.

There were a total of 3 congenital anomalies recorded for women who got pregnant during the study. One pregnancy in the C31G group resulted in a fetus with renal and cardiac malformations. This pregnancy was terminated, and the abnormalities were deemed unrelated to study drug. No additional congenital anomalies were identified among the 57 live births in the C31G group. In the Conceptrol group, 2 of 46 viable infants (4.3%) had congenital anomalies, one of whom was born with cardiac anomalies and the other with gastroschisis.

Acceptability of product was similar, with approximately three-fourths of women in each group reporting that they strongly or somewhat liked their assigned method after cycle 6 (or premature study exit). A similar proportion of women in each group said that they definitely or probably would use the product again. Acceptability was also high (89% in C31G vs. 86% in Conceptrol®, p=0.18) among the women who continued use of either product for 12 months.

Discussion

We compared the contraceptive efficacy, acceptability, and safety of spermicidal products containing C31G and nonoxynol-9 and found that C31G was non-inferior to nonoxynol-9 for efficacy, and that side effects were similar. Strengths of this study include the randomized, masked design, the large number of participants, and the rigorous follow up. In addition, participants were similar to those who might be expected to be typical users. They were young, sexually active women who tended to be users of nonhormonal contraception. More than two-thirds had proven fertility. Published studies of spermicide efficacy show a wide range of pregnancy rates, from 3.8% to as high as 29% (15). The 6-month pregnancy rates of about 12% for each product in the MITT population are consistent with rates seen in studies of nonoxynol-9. (16, 17, 18). Perfect-use pregnancy rates were about 5% with both products in our study. While on the low end of rates previously reported for perfect use of spermicides, it is consistent with rates reported for some nonoxynol-9 formulations. (12) This demonstrates that spermicides have the potential to provide efficacious contraception in women who can use them consistently and correctly.

Figure 2 indicates that a separation in pregnancy probability seems to occur at about 8 months, though the reasons for this are unclear. One might expect that those who continued in the study like their assigned product and therefore would be more likely to use it correctly and consistently; however, this should have been equally true for both groups. The sample size for the 6–12 month follow-up period was relatively small (Figure 1). The cumulative pregnancy probability estimates are therefore less precise, and the power to detect a real difference is low.

Although the percentage of women reporting EC use was significantly higher among the C31G users, this unexpected finding is likely spurious given the double-masked nature of the trial. Because cycles of EC use were excluded both from the numerator (pregnancies) and denominator in the efficacy analyses, this difference would not have a differential impact on pregnancy rates.

The incidence of serious adverse events was low with both products. None were related to C31G use, and only two were potentially related to nonoxynol-9 use. The proportion of women experiencing any adverse event potentially related to study product was higher in the nonoxynol-9 group. This seems due, at least in part, to higher rates of genital symptoms reported in that group (Table 4). However, rates of yeast vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, and urinary tract infections were low, and similar between groups. Only 2–3% of users cited adverse events as a specific reason for discontinuation. The rate of major congenital anomalies seen in this study is within the range expected in the general population (19).

Women who completed the study found the C31G product to be acceptable, with the majority reporting that they would use it again. It is notable that even in this clinical trial setting, over 20% of coital acts were associated with non-use or incorrect use of assigned spermicide. A recent review suggested that real-world acceptability and consistent use of spermicides are affected by social contexts that are not usually addressed in clinical trials. (20) Such factors may contribute in turn to the low real-world effectiveness (21) of spermicides. Consideration of social contexts may be increasingly relevant as new spermicidal products become available.

While male partners of subjects in our study were not directly surveyed, very few women reported that their partner had any adverse effects. Tolerability for male partners is obviously important, and evidence suggests that men are willing to use spermicides if they are shown to be safe and effective (22).

Limitations of the study include the high rate of discontinuation, which may reflect a level of unstated dissatisfaction with either study product. Approximately 50% of participants discontinued before 6 cycles of use, similar to rates reported from previous randomized trials of spermicides. (15, 23) Such high rates may raise concern for external validity (24). However, in our trial, the rate of discontinuation not related to pregnancy was similar to that seen in other studies of spermicide efficacy (15, 16). In one study, women who did not complete the spermicide trial were younger or unmarried, and had intercourse less frequently than those who completed the study (23). Our findings were similar: older and married women were more likely to complete the study than younger or unmarried women.

The findings of high satisfaction and acceptability at 6 months may, in part, reflect attrition of dissatisfied participants. Those who did not like their assigned contraceptive (or whose partners disliked it) may have been more likely to drop out. Acceptability data was collected from women who exited the study early, and this bias may be small; however, we have no acceptability information for the 11–12% of women lost to follow up in either group.

Because the study followed women for 12 months, we lack data about adverse events that may occur with longer term use. However, no post-study safety concerns have been reported. Finally, a potential benefit of spermicides is STI prevention. C31G is active in vitro against chlamydia, HIV, and HSV-2 (25–28). Published evidence suggests that neither N9 nor C31G confers protection against HIV transmission (29, 30). In our study, rates of acquisition of other STIs were too low to draw any conclusions about infection prevention.

Results of this randomized trial indicate that the contraceptive efficacy of C31G is non-inferior to that of nonoxynol-9. C31G is also safe and highly acceptable. The commercial availability of spermicidal products containing C31G will provide more options to women who seek a coitally-dependent, nonhormonal, nonprescription method of contraception.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following investigators for their contributions to this study: Anita L Nelson, MD and Ron Frezieres, MSPH, California Family Health Council, Los Angeles, CA; Lisa Keder, MD, The Ohio State University College. In addition, we would like to acknowledge James Higgins, PhD, and Clint Dart, MS, Health Decisions, for their valuable statistical expertise, and Trent Mackay, MD, MPH, Contraception and Reproductive Health Branch Chief, NICHD, Bethesda, MD, for his assistance with study design.

Funding Source: This study was sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Maryland, and Biosyn, Inc., Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

This clinical trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as:NCT00274261; Study of the Safety and Contraceptive Efficacy of C31G Compared to Conceptrol®. The URL can be found at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00274261?term=spermicide+AND+c31g&recr=Closed&rank=1

References

- 1.Mosher WD, Martinez GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Willson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Adv Data. 2004;(350):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darroch JE, Frost JJ. Women’s interest in vaginal microbicides. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31(1):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook RL, Rosenberg MJ. Do spermicides containing nonoxynol-9 prevent sexually transmitted infections? A meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25(3):144–150. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stafford MK, Ward H, Flanagan A, Rosenstein IJ, Taylor-Robinson D, Smith JR, et al. Safety study of nonoxynol-9 as a vaginal microbicide: evidence of adverse effects. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;17(4):327–331. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199804010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Damme L, Ramjee G, Alary M, Vuylsteke B, Chandeying V, Rees H, et al. COL-1492 Study Group. Effectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9338):971–977. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catalone BJ, Ferguson ML, Miller SR, Malamud D, Kish-Catalone T, Thakkar NJ, et al. Prolonged exposure to the candidate spermicide C31G differentially reduces cellular sensitivity to agent re-exposure. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(8):460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catalone BJ, Miller SR, Ferguson ML, Malamud D, Kish-Catalone T, Thakkar NJ, et al. Toxicity, inflammation, and anti-human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 activity following exposure to chemical moieties of C31G. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(8):430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauck CK, Weiner DH, Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Callahan MM, Bax R. A randomized phase I vaginal safety study of three concentrations of C31G vs. extra strength gynol II. Contraception. 2004;70:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mauck CK, Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Ballagh SA, Archer DF, Callahan MM, et al. A phase I comparative postcoital testing study of three concentrations of C31G. Contraception. 2004;70:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauck CK, Frezieres RG, Walsh TL, Schmitz SW, Callahan MM, Bax R. Male tolerance study of 1% C31G. Contraception. 2004;70:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machin D, Campbell MJ. Statistical Tables for Design of Clinical Trials. Oxford (England): Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. Analysis and samples. British J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JE, Wilkens LR. Statistical comparison of Pearl rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:656–659. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miettinen O. Estimability and estimation in case-referent studies. Am J Epidemiology. 1976;103(2):226–235. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimes DA, Lopez L, Raymond EG, Halpern V, Nanda K, Schulz KF. Spermicide used alone for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD005218. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005218.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raymond EG, Chen PL, Luoto J Spermicide Trial Group. Contraceptive effectiveness and safety of 5 Nonoxynol-9 spermicides: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(3):430–439. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000113620.18395.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnhart KT, Rosenberg MJ, MacKay HT, Blithe DL, Higgins J, Walsh T, et al. Contraceptive efficacy of a novel spermicidal microbicide used with a diaphragm: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):577–586. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000278078.45640.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mauck CK, Frezieres RG, Walsh TL, Peacock K, Schwartz JL, Callahan MM. Noncomparative contraceptive efficacy of cellulose sulfate gel. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):739–746. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181644598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY. "Chapter 13. Prenatal Diagnosis and Fetal Therapy" (Chapter) In: Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY, editors. Williams Obstetrics; [Last accessed August 9, 2010]. p. 23e.http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=6021591 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mantell JE, Myer L, Carballo-Diéguez A, Stein Z, Ramjee G, Morar NS, Harrison PF. Microbicide acceptability research: current approaches and future directions. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trussell J. Contraceptive efficacy. In: Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Stewart FH, Kowal D, editors. Contraceptive Technology. 19th Edition. New York (NY): Ardent Media, Inc.; 2007. pp. 747–826. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes WR, Maher L, Rosenthal SL. Attitudes of men in an Australian male tolerance study towards spermicide use. Sex Health. 2008;5(3):273–278. doi: 10.1071/sh07093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond EG, Chen PL, Pierre-Louis B, Luoto J, Barnhart KT, Bradley L, et al. Participant characteristics associated with withdrawal from a large randomized trial of spermicide effectiveness. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Sample size slippages in randomised trials: exclusions and the lost and wayward. Lancet. 2002;359:781–785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07882-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson KA, Malamud D, Storey BT. Assessment of the anti-microbial agent C31G as a spermicide: comparison with nonoxynol-9. Contraception. 1996;53:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebs FC, Miller SR, Malamud D, Howett MK, Wigdahl B. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by nonoxynol-9, C31G, or an alkyl sulfate, sodium dodecyl sulfate. Antiviral Res. 1999;43(3):157–173. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(99)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corner AM, Dolan MM, Yankell SL, Malamud D. C31G, a new agent for oral use with potent antimicrobial and antiadherence properties. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32(3):350–353. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.3.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyrick PB, Knight ST, Gerbig DG, Jr, Raulston JE, Davis CH, Paul TR, Malamud D. The microbicidal agent C31G inhibits Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41(6):1335–1344. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.6.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldblum PJ, Adeiga R, Wevill S, Lendvay A, Obadaki F, Olayemi O, et al. SAVVYvaginal gel (C31G) for prevention of HIV infection: a randomized controlled trial in Nigeria. W PLoS One. 2008;3(1):e147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001474. 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson L, Nanda K, Opoku BK, Ampofo WK, Owusu-Amoako M, Boakye AY, et al. SAVVY (C31G) gel for prevention of HIV infection in women: a Phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Ghana. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]