Abstract

Background

While the liver is a frequent site of metastatic spread for malignant cutaneous as well as malignant ocular melanoma, isolated hepatic metastases without evidence of systemic disease is rare. Hepatic resection has been proposed as a therapeutic and potentially curative procedure in metastatic melanoma patients with isolated hepatic metastases.

Objective

To report two metastatic melanoma patients with isolated hepatic metastases treated with partial hepatectomy. In addition, the literature is reviewed and the management and efficacy of surgical excision for isolated hepatic disease in the setting of malignant melanoma is discussed.

Case Report

A 34-year-old woman with metastatic cutaneous melanoma and a 55-year-old man with metastatic ocular melanoma are presented. Both patients developed isolated hepatic metastases detected during routine surveillance following resection of their primary disease and underwent partial hepatectomy.

Conclusion

In select cases, partial hepatectomy is an efficacious and potentially curative treatment for metastatic melanoma patients with isolated hepatic metastases.

Introduction

Melanoma incidence has steadily increased in the United States, from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 1992 to 19 cases per 100,000 population in 2007.1 The National Cancer Institute estimates that in 2010 alone, 68,130 new cases of melanoma were diagnosed, with 8,700 deaths.2 Melanoma is a significant problem in Hawaii, as the state has incidence rates near or slightly higher than the national average at 16.8 to 19.2 and mortality rates of 2.7 to 2.8 per 100,000 population.3 Compared with other skin malignancies, melanomas more commonly metastasize to local draining lymph nodes and to distant sites such as lung, liver and brain. Metastases can also occur years after initial presentation.4–6

The liver is a frequent site of metastases for both cutaneous and ocular melanomas. A study of 216 cutaneous melanoma cases found 58.3% had metatistic disease in the liver.7 More than 40% of newly diagnosed ocular melanomas have hepatic metastases present at initial diagnosis, and 95% of all ocular melanoma patients with metastatic disease have hepatic involvement at some point in their disease.8,9 Although hepatic involvement in metastatic melanoma is common, isolated hepatic metastasis is rare in cutaneous melanoma and occurs in about 46% of patients with ocular melanoma.10–12 Unfortunately, many of these patients are not candidates for surgical resection due to localization or extent of hepatic spread of disease.11 The infrequency of solitary hepatic metastasis and subsequent treatment provides an opportunity to discuss this rare situation. One patient with malignant cutaneous melanoma and a second patient with malignant ocular melanoma, both with isolated hepatic metastasis, treated with hepatectomy are presented and the literature on this topic is reviewed.

Case Reports

Case 1

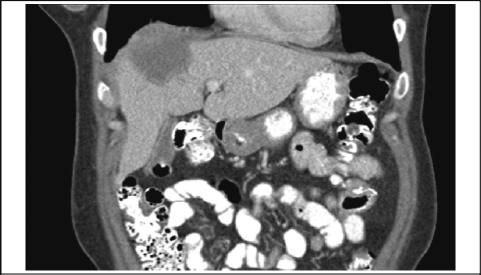

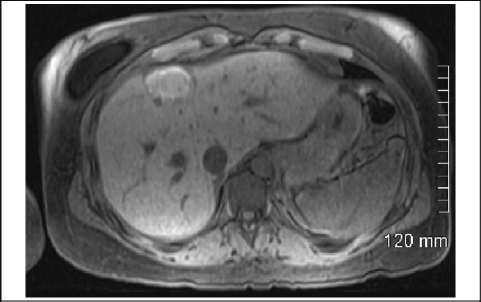

A 34-year-old woman with a 5.4 cm × 4.6 cm × 2.8 cm deep right arm cutaneous melanoma was treated with wide local excision, right axillary node dissection with 18 nodes negative for metastasis, and 9 months of interferon therapy. A 2.8 cm small bowel metastatic melanoma was resected 5 years later with clear margins. On follow-up 9 months later she was noted on computed tomography (CT) scan to have a 1.4 cm right hepatic mass, that biopsy confirmed to be malignant cutaneous melanoma. The patient received 2 cycles of cisplatin, vinblastine, temozolomide, and high-dose interleukin II as well as 2 cryoablative procedures. However, positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed continued increased uptake in the right hepatic lobe. Abdominal CT scan (Figure 1) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 2) demonstrated a 4.9 cm × 2.6 cm mass in the right lobe of the liver.

Figure 1.

CT Demonstrating Right Hepatic Mass

Figure 2.

MRI Demonstrating Right Hepatic Mass

Eighteen months after the initial discovery of the right hepatic mass, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy with right hepatic wedge resection of segments 4 and 8. A solitary 3.1 cm × 2.7 cm × 2.4 cm metastatic melanoma was resected showing 100% tumor ablation and margins free of disease. The patient recovered well; however, at 6 months after surgery she was found to have a suspicious mass noted in her anteromedial left hepatic lobe and gastrohepatic ligament on PET and CT, later confirmed to be melanoma by biopsy. More than 11 months after surgery, the patient underwent treatment with carboplatin and taxol with little response, and four rounds of ipilimumab with mild response. The patient is currently seeking further treatment options.

Case 2

A 55-year-old male with Stage III spindle cell B type (fascicular) ocular melanoma of his right eye was treated with right eye enucleation. He did not receive adjuvant therapy and was followed with serial CT imaging. Forty-one months after enucleation, CT demonstrated a 1.8 cm right posterior hepatic lesion in segments 5 and 6. PET demonstrated a 1.9 cm right hepatic lesion with mildly hypometabolic function, without further evidence of metastatic disease. Biopsy showed a lesion consistent with metastatic melanoma.

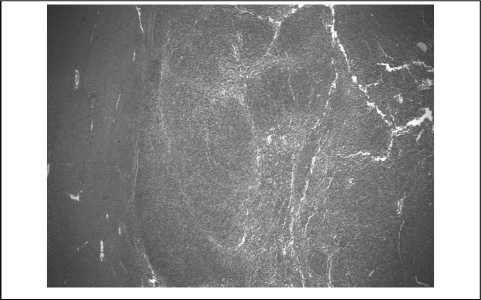

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy with right hepatic lobectomy. Pathologic examination grossly demonstrated 2 nodules measuring up to 1.7 cm × 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm within the excised hepatic tissue. Microscopic examination revealed the nodules contained elongated malignant cells arranged in a fascicular pattern associated with melanin pigment, consistent with ocular melanoma (Figure 4). The patient recovered well and had no evidence of disease on PET scan or MRI of the abdomen, neck, face, orbits, or brain 3 months after hepatic resection.

Figure 4.

Melanoma & Liver Parenchyma Interface

Discussion

Because melanomas can metastasize long after initial presentation, prolonged follow-up is recommended.4–6 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines suggest that all patients with melanoma have routine physician follow up, monthly self-conducted skin and lymph node exams, and annual physician skin and lymph node exams for life.4 NCCN also suggests that patients with melanomas greater than 2 mm or any evidence of nodal or micrometastasis consider follow-up with annual chest X-rays, PET/CT scans, and/or brain MRI, although routine radiologic studies show diminished yield more than five years after initial diagnosis.4 Although it is well established that surgical resection with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy is the standard of care for primary cutaneous melanoma, there is no consensus for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma.13 Similarly, there is currently no effective medical treatment for disseminated malignant ocular melanoma.9,14

The liver is a frequent site of metastasis in both malignant cutaneous and ocular melanoma.15 Classically, median survival after diagnosis of hepatic metastasis has ranged from 2 to 7 months.8 For cutaneous melanoma, 5-year survival was 3% and median survival in patients with metastasis to the liver was 4.4 months.16 Survival at 1-year in ocular melanoma with hepatic metastasis is 20%, with 5-year survival of 1%.10 While the liver is frequently involved with malignant melanoma, hepatic metastasis typically presents with concurrent widely disseminated disease.11 In these cases, chemotherapy is the treatment of choice.13 Treatment of hepatic metastatic melanoma with systemic chemotherapy has traditionally yielded a response rate of less than 1%. However, several new molecular-targeted therapies have shown greater success in phase III trials.9,17,18

In the case of isolated liver metastasis, treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, surgery, and a variety of other techniques for unresectable disease.13 Conventional chemotherapy has shown limited efficacy, and sustained remissions are not routinely achieved.13 Dacarbazine, which before 2010 was the only cytotoxic agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating metastatic cutaneous melanoma, demonstrates objective response rates from 5.5%–20%.13 Recently, phase III trials have shown efficacy for two novel molecular-targeted therapies.17,18 A treatment with Ipilimumab, an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 antibody, increased median overall survival time of 10.0 months compared to 6.4 months without the drug.17 Noted to have an immune-related adverse event rate of 10%–15%, ipilimumab was approved by the FDA for use in patients with advanced melanoma.17 Vemurafenib, a serine-threonine protein kinase B-RAF (BRAF) inhibitor, demonstrated a relative reduction of 74% in the risk of death or disease progression in melanoma patients with the BRAF V600E mutation, as compared to dacarbazine.18 Although 38% of patients required dose modification due to toxic side effects, including squamous-cell carcinoma, vemurafenib was subsequently approved by the FDA for treatment of metastatic melanoma with the BRAF V600E mutation.18 Patients with isolated hepatic metastasis but with unresectable disease due to number or localization of lesions have also been treated with a variety of other methods, including isolated hepatic perfusion, hepatic artery chemoembolization, hepatic artery infusion, and radio frequency thermal ablation.11,19 In smaller studies with sample sizes ranging between 19 to 181 patients, these other treatment modalities all demonstrated median survival between 9 and 15 months, except for radiofrequency ablation which demonstrated median survival of 18.5 months.19–25 Surgical resection has been performed in small studies of selected patients with isolated hepatic and pulmonary metastasis.11,13,26–28 Surgical resection of isolated hepatic metastasis has recently been demonstrated to achieve local control with improvement of median and 5 year survival.29

A review of the literature shows that patients with isolated hepatic metastasis who undergo surgical resection have a median survival ranging from 20–28 months with a 5 year survival ranging from 10.9% to as high as 53.3%, showing a longer median survival than for any other intrahepatic metastasis management technique. In a study of 40 patients with isolated hepatic metastases, 24 of whom had cutaneous melanoma and 16 of whom had ocular melanoma, Pawlik, et al, found that median survival time after hepatic resection was 28.2 months with a 5 year survival rate of 10.9%.30 Adam, et al, reported a 5 year survival after hepatic resection of 21%–22% in a study of 148 patients, including 44 cases of cutaneous melanoma and 104 cases of ocular melanoma.31 In a smaller study of 12 patients with ocular melanoma and isolated hepatic metastases, Aoyama, et al, found that surgical excision was beneficial and potentially curative in some cases. While 2 patients had residual disease present soon after hepatic resection, the other 10 patients had a median survival of longer than 27 months with a 5 year survival rate of 53.3%. The 2 patients who had residual disease survived 23 and 25 months post-resection, respectively. Four patients had all evidence of disease eliminated by surgery, although 1 required a second hepatic resection.29 Several other small studies of 9 to 22 patients with isolated hepatic metastasis from primary cutaneous and/or ocular melanoma demonstrated similar prolonged median survival of 20–28 months.26,32–36 All of these small trials reported a median survival that greatly exceeded the classic median survival after hepatic metastasis diagnosis.

Our first patient presented with isolated hepatic metastasis from cutaneous melanoma, and our second patient presented with isolated hepatic metastasis from ocular melanoma. Following resection, both patients recovered well and remained disease free for 6 months and 3 months, respectively. Although our first patient had disease recurrence in her liver, she remains active and seeking alternative treatment options more than a year after surgery, a time span already greatly exceeding the 4.4 month median survival for patients with cutaneous melanoma metastatic to the liver. Our second patient is healthy 3 months after surgery and shows no stigmata or sequelae of the resected hepatic disease.

Conclusion

Melanomas with isolated hepatic metastasis are rare but are more common in patients with primary ocular tumors or larger cutaneous melanoma with nodal involvement. These patients should be followed long-term as metastases can occur many years after resection of the primary tumor. Recommended monitoring includes regular physician follow-up, monthly skin and lymph node self-checks, annual physician skin and lymph node checks, and annual CT, PET/CT, or MRI for more advanced disease. Hepatic resections should be considered in patients with isolated hepatic metastasis, as this can prolong median and 5 year survival, and be potentially curative. Other modalities such as radiofrequency, isolated hepatic perfusion, or chemoembolization may be more appropriate for unresectable liver disease but have not been tested in large groups or compared directly to resection. Systemic chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy should be reserved for patients with disseminated metastatic disease or particular mutation subtypes of melanoma.

Figure 3.

9-Mo. Follow-Up CT Showing Right Hepatic Mass

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify any conflict of interest or report any financial disclosures.

References

- 1.StatBite: Melanoma incidence: 1992–2007. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:171. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melanoma Home Page -National Cancer Institute. [April 3, 2011]. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/melanoma.

- 3.CDC - Skin Cancer Rates by State. [October 13, 2011]. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/statistics/state.htm.

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. NCCN Melanoma Guidelines Version 2.2012. [November 29, 2011]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/melanoma.pdf.

- 5.Francken AB, Accortt NA, Shaw HM, Colman MH, Wiener M, Soong SJ, Hoekstra HJ, Thompson JF. Follow-up schedules after treatment for malignant melanoma. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1401–1407. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cumming K, Earle JD, Green DL, Hawkins BS, Hayman J, Jaiyesimi I, Kirkwood JM, Koh WJ, Robertson DM, Shaw JM, Thoma J. Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma: the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report 23. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2438–2444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel JK, Didolkar MS, Pickren JW, Moore RH. Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma: A study of 216 autopsy cases. Am J Surg. 1978;135:807–810. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman ED, Pingpank JF, Alexander HR., Jr Regional treatment options for patients with ocular melanoma metastatic to the liver. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:290–297. doi: 10.1245/aso.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedikian AY, Legha SS, Mavligit G, Carrasco CH, Khorana S, Plager C, Papadopoulos N, Benjamin RS. Treatment of uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver: a review of the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience and prognostic factors. Cancer. 1995;76:1665–1670. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951101)76:9<1665::aid-cncr2820760925>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cunmming K, Earle JD, Hawkins BS, Hayman JA, Jaiesimi I, Jampol LM, Kirkwood JM, Koh WJ, Robertson DM, Shaw JM, Straatsma BR, Thoma J. Development of metastatic disease after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma: Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report No. 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1639–1643. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vahrmeijer AL, van de Velde CJ, Hartgrink HH, Tollenaar RA. Treatment of melanoma metastases confined to the liver and future perspectives. Dig Surg. 2008;25:467–472. doi: 10.1159/000184738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eskelin S, Pyrhonen S, Summanen P, Hahka-Kemppinen M, Kivela T. Tumor doubling times in metastatic malignant melanoma of the uvea: tumor progression before and after treatment. Ophthlalmology. 2000;107:1443–1449. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Algazi AP, Soon CW, Daud AI. Treatment of cutaneous melanoma: current approaches and future prospects. Cancer Manag Res. 2010;2:197–211. doi: 10.2147/CMR.S6073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laver NV, McLaughlin ME, Duker JS. Ocular melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1778–1784. doi: 10.5858/2009-0441-RAR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert DM, Ryan LM, Borden EC. Metastatic Ocular and cutaneous melanoma: a comparison of patient characteristics and prognosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:107–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amersi FF, McElrath-Garza A, Ahmad A, Zogakis T, Allegra DP, Krasne R, Bilchik AJ. Long-term survival after radiofrequency ablation of complex unresectable liver tumors. Arch Surg. 2006;141:581–587. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Iersel LB, Hoekman EJ, Gelderblom H, Vahrmeijer AL, van Persijn van Meerten EL, Tijl FG, Hartgrink HH, Kuppen PJ, Nortier JW, Tollenaar RA, van de Velde CJH. Isolated hepatic perfusion with 200 mg melphalan for advanced noncolorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1891–1898. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9881-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander HR, Jr, Libutti SK, Pingpank JF, Steinberg SM, Bartlett DL, Helsabeck C, Beresneva T. Hyperthermic isolated hepatic perfusion using melphalan for patients with ocular melanoma metastatic to liver. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6343–6349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters S, Voelter V, Zografos L, Pampallona S, Popescu R, Gillet M, Bosshard W, Fiorentini G, Lotem M, Weitzen R, Keilholz U, Humblet Y, Piperno-Neumann S, Stupp R, Leyvraz S. Intra-arterial hepatic fotemustine for the treatment of liver metastases from uveal melanoma: experience in 101 patients. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:578–583. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel R, Hauschild A, Kettelhack C, Kahler KC, Bembenek A, Schlag PM. Hepatic arterial fotemustine chemotherapy in patients with liver metastases from cutaneous melanoma is as effective as in ocular melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:627–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyvraz S, Spataro V, Bauer J, Pampallona S, Salmon R, Dorval T, Meuli R, Gillet M, Lejeune F, Zografos L. Treatment of ocular melanoma metastatic to the liver by hepatic arterial chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2589–2595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shama KV, Gould JE, Harbour JW, Linette GP, Pilgram TK, Dayani PN, Brown DB. Hepatic arterial chemoembolization for management of metastatic melanoma. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:99–104. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herman P, Machado M, Montagnini AL, D'Albuquerque LA, Saad WA, Machado MC. Selected patients with metastatic melanoma from liver resection. World J Surg. 2007;31:171–174. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0375-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long-term results of lung metastectomy: prognostic analyses based on 5206 cases. The International Registry of Lung Metastases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(97)70397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alseidi A, Helton WS, Espat NJ. Does the literature support an indication for hepatic metastatectomy other than for colorectal primary? J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aoyama T, Mastrangelo MJ, Berd D, Nathan FE, Shields CL, Shields JA, Rosato EL, Rosato FE, Sato T. Protracted survival after resection of metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1561–1568. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1561::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pawlik TM, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Clary BM, Gershenwald JE, Ross MI, Aloia TA, Curley SA, Camacho LH, Capussotti L, Elias D, Vauthey JN. Hepatic resection for metastatic melanoma: distinct patterns of recurrence and prognosis for ocular versus cutaneous disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:607–609. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adam R, Chice L, Aloia T, Elias D, Salmon R, Rivoire M, Jaeck D, Saric J, Le Treut YP, Belghiti J, Mantion G, Mentha G. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases: analysis of 1,452 patients and development of a prognostic model. Ann Surg. 2006;244:524–535. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000239036.46827.5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elias D, Cavalcanti A, Eggenspieler P, Plaud B, Cucreux M, Spielmann M. Resection of liver metastases from noncolorectal primary: indications and results based on 147 monocentric patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:487–492. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kodjikian L, Grange JD, Baldo S, Bailif S, Garweg JG, Rivoire M. Prognostic factors of liver metastases from uveal melanoma. Grafe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:985–993. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-1188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caralt M, Marti J, Cortes J, Fondevila C, Bilbao I, Fuster J, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Sapisochin G, Balsells J, Charco R. Outcome of patients following hepatic resection for metastatic cutaneous and ocular melanoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0341-x. ePub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose DM, Essner R, Hughes TM, Tang PC, Bilchik A, Wanek LA. Surgical resection for metastatic melanoma to the liver. Arch Surg. 2001;136:950–955. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.8.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood T, DiFronzo A, Rose DM, Haigh PI, Stern SL, Wanek L. Does complete resection of melanoma metastatic to solid intra-abdominal organs improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:658–662. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]