Abstract

The presence of cholestasis in both mild and severe forms of acute biliary pancreatitis (ABP) does not justify, of itself, early endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) or endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES). Clinical support treatment of acute pancreatitis for one to two weeks is usually accompanied by regression of pancreatic edema, of cholestasis and by stone migration to the duodenum in 60%-88% of cases. On the other hand, in cases with both cholestasis and fever, a condition usually characterized as ABP associated with cholangitis, early ES is normally indicated. However, in daily clinical practice, it is practically impossible to guarantee the coexistence of cholangitis and mild or severe acute pancreatitis. Pain, fever and cholestasis, as well as mental confusion and hypotension, may be attributed to inflammatory and necrotic events related to ABP. Under these circumstances, evaluation of the bile duct by endo-ultrasonography (EUS) or magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) before performing ERC and ES seems reasonable. Thus, it is necessary to assess the effects of the association between early and opportune access to the treatment of local and systemic inflammatory/infectious effects of ABP with cholestasis and fever, and to characterize the possible scenarios and the subsequent approaches to the common bile duct, directed by less invasive examinations such as MRC or EUS.

Keywords: Biliary pancreatitis, Cholestasis, Endoscopic sphincterotomy, Cholangitis, Mortality, Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, Endoscopic ultrasonography, Intensive care, Health system regulation

INTRODUCTION

The association between acute pancreatitis (AP) and the migration of gallbladder stones and sludge to the common bile duct and the intestinal lumen, the possibility that impaction of these stones in the ampulla of Vater will worsen the pancreatic injuries[1-4] and the detection of an impacted stone at autopsy in about half the cases of acute biliary pancreatitis (ABP)[5] have contributed to the adoption of early endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) in ABP. The incorporation of diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy into clinical practice, technology diffusion due to market forces and the influence of studies published in the last decades of the 20th century[6-8] have also been determinant factors in the adhesion to early ERC and ES in ABP.

However, on the basis of the results of recent studies and meta-analyses[9-13], as well as critical analyses[14,15], it has been concluded that the systematic adoption of early ERC followed by ES for ABP has exposed many patients to invasive diagnosis and unnecessary surgery. The most recent meta-analysis based on three prospective and randomized studies did not demonstrate any influence of ERC (with or without ES) on the morbidity or mortality rates of patients with mild or severe ABP, without cholangitis[13]. The conceptual difficulties for the characterization of ABP associated with cholangitis were reported in these studies, but aspects related to the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to this condition are treated in a consensual manner.

The similar incidence of the severe form of AP in the different etiologies established in the literature[16,17] supports the thesis that the magnitude of the pancreatic insult can be pre-established at the start of the clinical manifestations, and the course of the initiated ABP episode may not be influenced by ERC or ES[12-18]. Thus, the theory that the migration of small gallstones can trigger the onset of ABP and that their repeated passage, the impaction of the ampulla of Vater with larger stones[3,4] or the persistence of biliopancreatic obstruction may induce progression to the severe form of ABP[11] is still a matter of speculation.

Based on primary and secondary evidence[15], circumstances that delay access to reference services and clinical practice seem to contribute to the adoption of a more conservative approach to the management of the common bile duct in ABP, as demonstrated by a study performed in the United Kingdom, in which the application of the protocol of the British Society of Gastroenterology was found not to be homogeneous. Only 45 of 93 (48%) patients with severe ABP, particularly those with signs of biliary obstruction and cholangitis, were subjected to ERC and ES, and no increase in complications or mortality was detected[19].

The impaction of a gallstone in the common bile duct was recorded in 26% to 72% of ABP patients when surgery was performed in the early phase and was recorded in less than 10% of patients operated upon in an elective manner[20,21]. Spontaneous disobstruction of the bile duct was demonstrated in 71% to 88% of cases within 48 hours of the onset of ABP, with no changes in the course of the disease[2,3]. The spontaneous relief of cholestasis and of biliopancreatic obstruction assessed by endo-ultrasonography (EUS) followed by ERC in patients referred to a reference service with ABP plus cholestasis and/or cholangitis, ranged from 56% to 75%[9,10]. Reduction of pain and of hyperbilirubinemia was observed in 62% of the patients within 48 hours of the onset of ABP symptoms[11], and 60% of the patients subjected to conservative treatment did not present choledocholithiasis during elective surgery [cholecystectomy and intraoperative cholangiography (IC)] performed during the same hospitalization[12].

Thus, conservative treatment, in addition to producing equivalent results in terms of morbidity and mortality compared to early ERC and ES, also contributes to a reduction of the incidence of choledocholithiasis and consequently of the need for early ERC and ES, thus avoiding the possible complications of these procedures. Pain, dilation of the bile duct at admission, jaundice and/or increased bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, gammaglutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels may be of help in selecting the method with which to image the bile duct, although they are not sufficient to determine a decision about ES since they may only reflect transitory changes due to stone migration, edema or other pancreatic injuries.

Within this context, nuclear magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) and EUS are less invasive methods that can identify choledocholithiasis with high accuracy in the presence of persistent and painful cholestasis and are beginning to be incorporated in evaluation of the bile duct under ABP by American, European and Asian guidelines[9,22-26].

Finally, the indication of early ERC and ES for ABP and the related association with cholangitis is well-established. However, it is practically impossible to guarantee the coexistence of cholangitis and mild or severe pancreatitis with cholestasis and fever in daily clinical practice, in an effort to institute ERC with early ES in a systematic manner. Fever and cholestasis may be attributed only to the inflammatory and necrotic events of ABP and, under these circumstances, the evaluation of the bile duct by MRC or EUS seems to be reasonable before performing ERC or ES.

Thus, the objective of the present editorial is to explore data on the effects of the association of early and opportune access to treat local and systemic inflammatory/infectious effects of ABP with cholestasis (associated or not with fever). The subsequent approach to the common bile duct can be guided by less invasive methods such as MRC and EUS.

MANAGEMENT OF BILIARY LITHIASIS IN ACUTE PANCREATITIS

The concept that AP in the early phase (approximately the first two weeks) is an inflammatory disease with or without necrosis and hemorrhage and localized clinical (mild form) or systemic manifestations (severe form) is widely accepted. Clinical support measures aimed at hydroelectric, cardiorespiratory and renal changes plus analgesia in the early phase of AP, should be proportional to the magnitude of the physiological and clinical changes. They can be applied in clinical stabilization rooms of emergency centers, on the clinical or surgical wards and in the intensive care units, with the participation of different specialists.

Invasive procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary disease and of eventual residual pancreatic injuries in ABP are currently postponed from the early to the late phase of the disease, usually starting during the second week after the onset of symptoms. Thus, the excessive pressure on emergency and intensive care physicians to perform the CER and EE (habitually within 48 to 72 hours) or to employ surgical, percutaneous or endoscopic procedures for material collections and pancreatic necrosis during the early phase is incompatible with the currently available evidence.

The rate of complications after diagnostic ERC is significant (5% to 10%), and the mortality rate is not negligible (0.07% to 0.1%). When ES is added to ERC, the rate of complications ranges from 7% to 10% and the mortality rate from 0.2% to 2.2%[27-31]. In addition, clinical and scientific evidence does not support the argument that stone impaction in the biliopancreatic confluence aggravates pancreatitis[1-3] or that the migration of small stones from the gallbladder to the choledochus and their passage into the duodenum would cause mild acute pancreatitis and prepare the path for the migration of larger gallstones that might impact the biliopancreatic confluence and cause severe pancreatitis[4].

The controversy about the effect of early ERC and ES performed in patients with ABP and cholestasis has decreased. A study of ES performed within 48 h of admission in patients with a bile duct measuring ≥ 8 mm in diameter and with total bilirubin ≥ 1.20 mg/dL revealed choledocholithiasis in 72% of cases[12]. A second group of patients in the same study, with similar clinical and demographic conditions and treated conservatively, presented choledocholithiasis in 40% of cases, as identified by IC performed in elective biliary surgery during the same hospitalization. However, despite the elevated persistence of choledocholithiasis in the conservatively treated group, these patients did not show either progression of the pancreatic or peripancreatic injuries or worsening of the pancreatitis severity score. In addition, morbidity and mortality rates were similar for the two groups[12].

The incidence of choledocholithiasis detected by EUS in patients with ABP with and without cholestasis during a period of 3 d after the onset of symptoms was 33%, significantly higher than the 18% rate detected in examinations performed after 3 d. Although the patients with severe pancreatitis were submitted to early EUS more frequently than patients with the mild form of the disease, no relationship was observed between disease severity and the presence of gallstones. The presence of gallstones was significantly higher in patients with jaundice and cholangitis (44%) than among patients without jaundice (19.5%)[9]. A study of the common bile duct of 110 patients with ABP without separating the group with cholestasis, conducted within 24 h of admission and after a maximum of 60 hours from the onset of symptoms, detected a 40% rate of choledocholithiasis[10].

Thus, in ABP with cholestasis and without cholangitis, it is possible to observe the evolution of the clinical manifestations and of cholestasis. If possible, it is advisable to wait for the regression of pancreatic inflammation and stone migration, and to then select the most appropriate imaging modality to confirm disobstruction of the common bile duct.

A careful meta-analysis including three prospective and randomized studies (which were not, however, homogeneous regarding the characterization of the time for ERC and ES, the definition of cholangitis and complications, and laboratory and imaging stratification of cholangitis) did not demonstrate a beneficial effect of ERC with or without early ES on mild or severe ABP without cholangitis. Of the 450 patients studied, 230 were allocated to early ERC and 220 to conservative treatment, but only half of those subjected to early evaluation presented lithiasis in the common bile duct[13]. Among the group subjected to early investigation and treatment, ERC was performed in 214 patients (93%), ES was performed in 114 patients (53%), and lithiasis was removed in 111 patients (52%). The rate of ERC complications was 2%. In the group undergoing conservative treatment (220 patients), ERC was performed in 33 patients (15%), and ES with stone removal was performed in 14 cases (43%). In this group, there were no complications after ERC. Overall evaluation showed that the incidence of choledocholithiasis was 48% following early endoscopic treatment and 6% following conservative treatment. These findings underscore the need to characterize patient groups for selective diagnosis and treatment.

Thus, the clinical, laboratory and imaging characterization of the involvement of the common bile duct in ABP can define the various possible scenarios and thus guarantee greater selectivity in investigation and treatment. The results obtained with conservative treatment of ABP permit us to conclude that cholestasis can regress or persist with or without fever and pain, within a short period of time.

The levels of bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) are within normal limits in 14.5%, 12.3%, 11.2% and 26.4% of ABP cases, respectively. Overall evaluation shows that about 15% to 20% of patients with ABP have markers of cholestasis within normal limits[32]. On the other hand, 92% of the patients with ABP who presented 4 or 5 changes in a defined set of variables evaluated upon admission (diameter of the choledochus ≥ 9 mm, ALP ≥ 250 U/L, gamma-glutamyltransferase≥ 350 U/L, total bilirubin ≥ 3 mg/dL and direct bilirubin ≥ 2 mg/dL)

presented lithiasis in the common bile duct[33]. Thus, patients with ABP may be admitted without cholestasis, with residual cholestasis due to the passage of the stone and to pancreatic edema, with cholestasis due to the persistence of the stone in the bile duct, or with cholangitis.

The relative sensitivity of MRC, ERC and EUS for the detection of lithiasis in the common bile duct, taking as reference the extraction of gallstones by ES, is 80%, 90% and 95%, respectively [34]. MRC has high sensitivity (94%-100%) and specificity (91%-98%) in the detection of gallstones in ABP when IC and ERC are taken as reference[35,36], although sensitivity is greatly reduced in the presence of gallstones smaller than 6 mm[34]. It should also be emphasized that the value of MRC and EUS in the detection of choledocholithiasis and of biliopancreatic obstruction has been unequivocally demonstrated in two meta-analyses[37,38], with these methods appearing to be determinant factors for the indication of ES in ABP.

On the basis of the clinical and laboratory characterization of cholestasis and of the anesthetic surgical risk to patients, it is possible to define scenarios based on the use of more sensitive and less invasive imaging exams for the detection of gallstones, microstones and bile sludge. The selection of endoscopic treatment based on echoendoscopy[10] may eventually impact the treatment of ABP and provide greater safety for the patients, as well as a more rational use of health care system resources.

DIFFERENT PRESENTATIONS OF ACUTE BILIARY PANCREATITIS AND ALTERNATIVES FOR MANAGEMENT

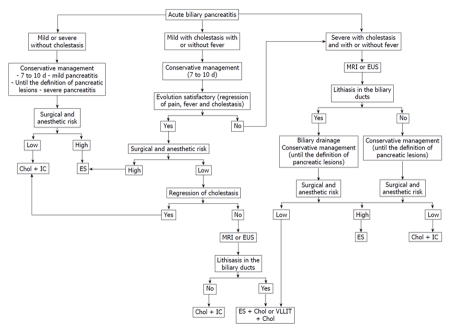

Patients with ABP who progress with regression of abdominal pain and cholestasis and who present a low anesthetic surgical risk can be subjected to cholecystectomy and IC alone, usually during the same hospitalization, about one week after the onset of symptoms. Videolaparoscopic choledocholithotomy is indicated when lithiasis identified by IC persists in the common bile duct. Patients with choledocholithiasis identified by IC that is not treated during cholecystectomy or patients with a high anesthetic surgical risk can be treated by ES (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm for the management of gallstones in different scenarios of acute biliary pancreatitis. Chol: Cholecystectomy; ES: Endoscopic sphincterotomy; VLLIT: Videolaparoscopic choledocholithotomy; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasonography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; IC: Intraoperative cholangiography.

When cholestasis and pain persist, evaluation of the common bile duct by MRC or EUS appears to be reasonable and, in the presence of choledocholithiasis, ES followed by cholecystectomy is a good option, performed prefereably during the same hospitalization for patients with low anesthetic surgical risk. In patients who develop pancreatic injury (necrosis, peripancreatic fluid collection), it is preferable to postpone cholecystectomy until the evolution of these lesions can be defined, as they frequently regress or are converted to infected necrosis, abscesses or pseudocysts that can be treated endoscopically (Figure 1).

Finally, studies have unanimously recommended early ERC and EUS in cholangitis. However, it is practically impossible in clinical practice to ensure the coexistence of cholangitis and mild or severe acute pancreatitis with cholestasis and fever, in order to instigate ERC with early ES. Fever and cholestasis can be attributed only to the inflammatory and necrotic events of ABP and, under these circumstances, evaluation of the bile duct by MRC or EUS before performing ERC and ES also seems reasonable.

The reported incidence of cholangitis in association with ABP ranges from 2.5% to 20%[6,7,11] and although it does not have a unique definition. Thus, the definition of the two conditions is borrowed and Charcot’s triad may simply represent either the manifestation of mild acute biliary pancreatitis with cholestasis and fever or a true association of these symptoms with cholangitis. Additionally, the presence of Reynold’s pentad (Charcot’s triad plus mental confusion and hypotension) may not be the manifestation of acute biliary pancreatitis with cholestasis, but may also represent an association with severe cholangitis. Thus, the time and mode of assessment of the biliary pathway, as well as the treatment of lithiasis, should be based on the possible association of the recommendations for ABP and cholangitis. On this basis, the systematic indication of ERC plus ES, especially in the case of mild presentation of the association of ABP with cholangitis, is not justified.

Patients with acute cholangitis associated with ABP can, when both conditions are in the mild form, be treated by admission to hospital and treatment with hydration and antibiotics (first- or second-generation cephalosporin or penicillin plus a β-lactamase inhibitor) for two or three days. Patients with moderate or severe cholangitis associated with ABP should be treated with fluid replacement, vasoactive amines, respiratory support and antibiotics for 5 to 7 d (penicillin plus a β-lactamase inhibitor and third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins possibly combined with metronidazole). A second line of antibiotics consisting of quinolone with or without metronidazole or carbapenemic agents can also be used [39]. Selection of the antibiotic could be adjusted depending on other variables present upon admission of patients with AP, such as hepatic and renal functional status.

The time for biliary disobstruction in cholangitis is related to the severity of the presentation of the condition. In the mild and moderate forms with good response to clinical treatment, disobstruction may be elective. In moderate cholangitis with an unfavorable course over a period of 24 to 48 h or in severe cholangitis, the need for biliary disobstruction is urgent. The use of a guide-wire and a minimal use of contrast in the biliopancreatic pathway are highly recommended, in order to prevent the worsening of cholangitis and pancreatitis. The installation of a nasobiliary catheter or prosthesis is preferable to the use of ES, especially in patients with clotting disorders. However, a response to clinical treatment occurs in 80% of cases and the need for urgent biliary disobstruction is rare[40,41]. These observations coupled with the characteristics of public health systems and possible access to a reference hospital and its services have definitely influenced the management of ABP cases associated with and without cholangitis[42,43].

CONCLUSION

Over recent decades, the surgical treatment of biliary lithiasis and of its pancreatic complications has shifted from the early to the late phase, preferentially with the use of minimally invasive techniques, and with a need for specialized services and the participation of the various clinical specialists, concentrated in tertiary health services.

Within the context of the dynamic and diverse course of ABP patients with different care needs and of the management of patient flow, the definition of priorities and the appropriate access to services, resources and specialists are a challenge and may impair the application of the clinical decisions recommended in protocols and consensuses[19,42-45].

Conservative treatment of ABP with cholangitis, similar to what occurs in cases without cholangitis, shows rates of spontaneous clearance of the common bile duct within two weeks of approximately 70%. Spontaneous clearance of the common bile duct prevents unnecessary invasive procedures that pose the risk of aggravating cholangitis and pancreatic inflammation.

In mild ABP associated with cholestasis and fever, despite the limitations in cholangitis characterization, the systematic application of early ERC and ES or of EUS and MRC is not justified. Under these circumstances, in addition to the limitations for the differentiation between inflammatory pancreatic disease and cholangitis, the recommendations for the treatment of mild and moderate cholangitis and ABP are conservative and therefore convergent. On the other hand, in the presence of severe ABP with cholangitis, EUS or MRC could guide the indication of bile duct decompression.

Thus, despite the limitations involved in controlled clinical studies of patients with ABP, the arguments presented, together with the recent critical literature reviews regarding ABP and cholangitis[13,15,39,40], support the hypothesis of conservative treatment of ABP when the condition is accompanied by fever and hyperbilirubinemia.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Calogero Iacono, MD, Professor, Department of Surgery, University Hospital “GB Rossi”, Verona 37134, Italy

Supported by Fundação Waldemar Barnsley Pessoa

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Acosta JM, Ledesma CL. Gallstone migration as a cause of acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1974;290:484–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197402282900904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acosta JM, Rubio Galli OM, Rossi R, Chinellato AV, Pellegrini CA. Effect of duration of ampullary gallstone obstruction on severity of lesions of acute pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acosta JM, Pellegrini CA, Skinner DB. Etiology and pathogenesis of acute biliary pancreatitis. Surgery. 1980;88:118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neoptolemos JP. The theory of 'persisting' common bile duct stones in severe gallstone pancreatitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1989;71:326–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer AD, McMahon MJ, Benson EA, Axon AT. Operations upon the biliary tract in patients with acute pancreatitis: aims, indications and timing. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66:179–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, London NJ, Bailey IA, James D, Fossard DP. Controlled trial of urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment for acute pancreatitis due to gallstones. Lancet. 1988;2:979–983. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90740-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan ST, Lai EC, Mok FP, Lo CM, Zheng SS, Wong J. Early treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis by endoscopic papillotomy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fölsch UR, Nitsche R, Lüdtke R, Hilgers RA, Creutzfeldt W. Early ERCP and papillotomy compared with conservative treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis. The German Study Group on Acute Biliary Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:237–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prat F, Edery J, Meduri B, Chiche R, Ayoun C, Bodart M, Grange D, Loison F, Nedelec P, Sbai-Idrissi MS, et al. Early EUS of the bile duct before endoscopic sphincterotomy for acute biliary pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:724–729. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.119734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CL, Lo CM, Chan JK, Poon RT, Lam CM, Fan ST, Wong J. Detection of choledocholithiasis by EUS in acute pancreatitis: a prospective evaluation in 100 consecutive patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:325–330. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acosta JM, Katkhouda N, Debian KA, Groshen SG, Tsao-Wei DD, Berne TV. Early ductal decompression versus conservative management for gallstone pancreatitis with ampullary obstruction: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2006;243:33–40. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000194086.22580.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oría A, Cimmino D, Ocampo C, Silva W, Kohan G, Zandalazini H, Szelagowski C, Chiappetta L. Early endoscopic intervention versus early conservative management in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis and biliopancreatic obstruction: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:10–17. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000232539.88254.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, van der Heijden GJ, van Erpecum KJ, Gooszen HG. Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg. 2008;247:250–257. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815edddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitale GC. Early management of acute gallstone pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:18–19. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250967.32581.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrov MS. Early use of ERCP in acute biliary pancreatitis with(out) jaundice: an unjaundiced view. JOP. 2009;10:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhl W, Isenmann R, Curti G, Vogel R, Beger HG, Büchler MW. Influence of etiology on the course and outcome of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1996;13:335–343. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199611000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halonen KI, Leppaniemi AK, Puolakkainen PA, Lundin JE, Kemppainen EA, Hietaranta AJ, Haapiainen RK. Severe acute pancreatitis: prognostic factors in 270 consecutive patients. Pancreas. 2000;21:266–271. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200010000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly TR, Elliott DW. Proper timing of surgery for gallstone pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1990;159:361–362. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mofidi R, Madhavan KK, Garden OJ, Parks RW. An audit of the management of patients with acute pancreatitis against national standards of practice. Br J Surg. 2007;94:844–848. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly TR. Gallstone pancreatitis: pathophysiology. Surgery. 1976;80:488–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acosta JM, Rossi R, Galli OM, Pellegrini CA, Skinner DB. Early surgery for acute gallstone pancreatitis: evaluation of a systematic approach. Surgery. 1978;83:367–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stabuc B, Drobne D, Ferkolj I, Gruden A, Jereb J, Kolar G, Mlinaric V, Mervic M, Repse A, Stepec S, et al. Acute biliary pancreatitis: detection of common bile duct stones with endoscopic ultrasound. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:1171–1175. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32830a9a31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022–2044. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Sekimoto M, Hirota M, Takeda K, Isaji S, et al. JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: treatment of gallstone-induced acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:56–60. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Geenen EJ, van der Peet DL, Bhagirath P, Mulder CJ, Bruno MJ. Etiology and diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:495–502. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 3:iii1–iii9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.057026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–918. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erickson RA, Carlson B. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:252–263. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherman S, Ruffolo TA, Hawes RH, Lehman GA. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy. A prospective series with emphasis on the increased risk associated with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and nondilated bile ducts. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1068–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, De Bernardin M, Ederle A, Fina P, Fratton A. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dholakia K, Pitchumoni CS, Agarwal N. How often are liver function tests normal in acute biliary pancreatitis? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:81–83. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telem DA, Bowman K, Hwang J, Chin EH, Nguyen SQ, Divino CM. Selective management of patients with acute biliary pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2183–2188. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moon JH, Cho YD, Cha SW, Cheon YK, Ahn HC, Kim YS, Kim YS, Lee JS, Lee MS, Lee HK, et al. The detection of bile duct stones in suspected biliary pancreatitis: comparison of MRCP, ERCP, and intraductal US. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1051–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hallal AH, Amortegui JD, Jeroukhimov IM, Casillas J, Schulman CI, Manning RJ, Habib FA, Lopez PP, Cohn SM, Sleeman D. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography accurately detects common bile duct stones in resolving gallstone pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:869–875. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makary MA, Duncan MD, Harmon JW, Freeswick PD, Bender JS, Bohlman M, Magnuson TH. The role of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the management of patients with gallstone pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:119–124. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149509.77666.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrow D, Miller S, Sinha D, Conway J, Hoffman BJ, Hawes RH, Romagnuolo J. Endoscopic ultrasound: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected biliary obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romagnuolo J, Bardou M, Rahme E, Joseph L, Reinhold C, Barkun AN. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected biliary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:547–557. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka A, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Yoshida M, Miura F, Hirota M, Wada K, Mayumi T, Gomi H, et al. Antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1157-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JG. Diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:533–541. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Attasaranya S, Fogel EL, Lehman GA. Choledocholithiasis, ascending cholangitis, and gallstone pancreatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:925–960, x. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carvalho FR, Santos JS, Elias Junior J, Kemp R, Sankarankutty AK, Fukumori OY, Souza MC, Castro-e-Silva O. The influence of treatment access regulation and technological resources on the mortality profile of acute biliary pancreatitis. Acta Cir Bras. 2008;23 Suppl 1:143–150; discussion 150. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502008000700023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopes SL, Dos Santos JS, Scarpelini S. The implementation of the Medical Regulation Office and Mobile Emergency Attendance System and its impact on the gravity profile of non-traumatic afflictions treated in a University Hospital: a research study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:173. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santos JS, Kemp R, Sankarankutty AK, Salgado Júnior W, Souza FF, Teixeira AC, Rosa GV, Castro-e-Silva O. Clinical and regulatory protocol for the treatment of jaundice in adults and elderly subjects: a support for the health care network and regulatory system. Acta Cir Bras. 2008;23 Suppl 1:133–142; discussion 142. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502008000700022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]