Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that a multimodal intervention giving the general practitioner (GP) an enhanced role in cancer rehabilitation improves patients' health-related quality of life and psychological distress.

Design

Cluster randomised controlled trial. All general practices in Denmark were randomised to an intervention group or to a control group. Patients were subsequently allocated to intervention or control (usual procedures) based on the randomisation status of their GP.

Setting

All clinical departments at a public regional hospital treating cancer patients and all general practices in Denmark.

Participants

Adult patients treated for incident cancer at Vejle Hospital, Denmark, between 12 May 2008 and 28 February 2009. A total of 955 patients (486 to the intervention group and 469 to the control group) registered with 323 general practices were included.

Intervention

The intervention included an interview about rehabilitation needs with a rehabilitation coordinator at the regional hospital, information from the hospital to the GP about individual needs for rehabilitation and an encouragement of the GP to contact the patient to offer his support with rehabilitation.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was health-related quality of life measured 6 months after inclusion using the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30). Secondary outcomes included quality of life at 14 months and additional subscales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 at 6 and 14 months and psychological distress at 14 months using the Profile of Mood States Scale.

Results

No effect of the intervention was observed on primary and/or secondary outcomes after 6 and 14 months.

Conclusion

A multimodal intervention aiming to give the GP an enhanced role in cancer patients' rehabilitation did not improve quality of life or psychological distress.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, registration ID number NCT01021371.

Article summary

Article focus

Cancer patients experience a wide range of problems during and after treatment. Unmet rehabilitation needs are frequent.

GPs are expected to play a central role in cancer rehabilitation.

We tested the impact of a multimodal intervention aiming at enhancing GP involvement in cancer rehabilitation on quality of life and psychological distress of the patients.

Key messages

A multimodal intervention comprising a patient interview about unmet needs and an encouragement to the GP to initiate the rehabilitation process did not improve quality of life or psychological distress of cancer patients.

Interventions aiming to give the GP an enhanced role in cancer rehabilitation seem to have difficulties improving quality of life.

Future studies should evaluate the importance of GP involvement in and the organisation of cancer treatment and rehabilitation.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study is the largest of its kind evaluating effect of GP involvement in cancer rehabilitation targeting a broad group of patients.

Albeit relevant and well-validated outcome measures were used, some sorts of effects of the intervention may not have been detected.

Background

Addressing the unmet needs of individual rehabilitation of cancer patients is paramount.1–4 The underlying problems are often psychological or social and many persist after treatment or emerge late in the illness continuum.5–8 Rehabilitation is defined by WHO as ‘a process intended to enable people with disabilities to reach and maintain optimal physical, sensory, intellectual, psychological and/or social function’9 which is the conceptual frame for this study. Hence, rehabilitation is a complex and long-lasting process, but evidence on how and when to identify the patients' needs, what initiatives to offer and how to manage the efforts is sparse.2 10–13

General practice is characterised by continuity with frequent encounters with each patient, covering wide-ranging issues.14 Hence, general practitioners (GPs) generally have profound knowledge about the patients' prior health status, mental vulnerability and social network. General practice may, therefore, be able to initiate the rehabilitation process and take on the task of coordinating or providing the rehabilitation services needed, but currently the role of GPs is not well defined.15–23 Studies do, however, show that GPs are willing to undertake these tasks and that the patients wish that their GPs were more proactive in doing so.21 24

The objective of this trial was to investigate the effect of a multimodal intervention giving the GP an enhanced role in improving patients' health-related quality of life and psychological distress following cancer. To validate our results, we conducted subgroup analyses of the large and homogeneous group of breast cancer patients.

Material and methods

We conducted a cluster randomised controlled trial, where all general practices in Denmark were randomised to an intervention group or to a control group by means of the unique provider number of each practice. Patients were subsequently allocated according to the randomisation of their GP. Feasibility of the intervention and the study details has previously been published.25

Participants

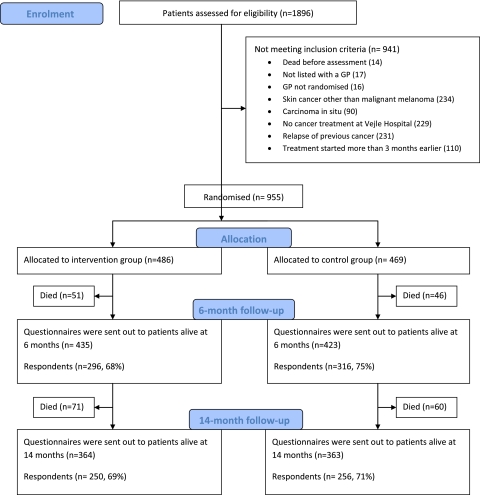

All adult patients (≥18 years) newly diagnosed as having cancer and admitted to Vejle Hospital between 12 May 2008 and 28 February 2009 were assessed for eligibility. Patients were included if treated at Vejle Hospital for a cancer diagnosed within the last 3 months and if listed with a general practice. Patients with carcinoma in situ or non-melanoma skin cancers were not included (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow. GP, general practitioner.

Two rehabilitation coordinators, both nurses with oncological experience, assessed all patients for eligibility and managed the intervention. The patients were sampled across departments, type of cancer, stage and potential rehabilitation needs by use of the electronic patient files.25

Setting

The study was conducted at Vejle Hospital, a public general hospital in the region of Southern Denmark (1.2 million inhabitants).26 Cancer patients were allocated from all departments treating cancer at Vejle Hospital, and could in principle be residents from all parts of Denmark.

The Danish publicly funded healthcare system ensures free access to general practice, which is responsible for primary care needs, and GPs function as gatekeepers to the rest of the healthcare system. More than 98% of all Danish residents are registered with a general practice. On average, each GP meets nine incident cancer patients during 1 year.27

GPs' opportunities to refer patients to relevant rehabilitation services vary between the different municipalities, just as the availability of private patient associations and other relief organisations. These conditions might influence the quality of the rehabilitation interventions offered.

The intervention

The intervention comprised a patient interview about rehabilitation needs performed by the rehabilitation coordinators, followed by information to the GP about the patient's individual rehabilitation needs and cancer patients' rehabilitation needs in general. The core of the information was that the GP was encouraged to contact the patient to facilitate a rehabilitation process (table 1).

Table 1.

General needs and problems among cancer patients

| Psychological level |

|

| Social level |

|

| Physical level |

|

| Work-related level |

|

| Financial level |

|

The patient interviews were conducted according to an interview guide28 and based on a checklist of general needs and problems among cancer patients (table 1). Interviews were most often conducted at the hospital but in some cases, by phone. During the interview, the concept of rehabilitation was explained and the individual needs for physical, psychological, sexual, social, work-related and economy-related rehabilitation were identified. It was explained that physical, psychological, sexual, social, work-related and financial issues1–4 29 might occur at any time and change during the disease trajectory.7 8 In order to address these problems, patients were advised to consult their GP during treatment and after discharge. The patients gave oral consent first to their GPs being informed as to their individual problems and needs and second to their GPs being encouraged to be proactive regarding the patients' rehabilitation.

Following each interview, the patient's GP was informed about the patient's actual problems and needs for rehabilitation and encouraged to be proactive, that is, the GP was encouraged to contact the patient personally to offer support and guidance in order to identify and address actual and future needs for rehabilitation. Subsequently, the GP received an email summarising the information, supplemented by general information about cancer patients' needs and problems (table 1). The information was personally conveyed by phone, if possible, and always sent electronically along with the more general information. Patients and GPs in the control group received the usual care and were not contacted by the rehabilitation coordinators.25

Outcomes and sampling of data

The primary outcome was health-related quality of life measured 6 months after inclusion using the Global Health Status of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30).30 31 The secondary outcomes were psychological distress at 14 months assessed by the six scales of the Profile of Mood States32 (depression/dejection, anger/hostility, tension/anxiety, vigour/activity, fatigue/inertia and confusion/bewilderment) and the Global Health Status at 6 months and functional (physical, emotional, role, cognitive or social functioning) and symptom scales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea or financial difficulties) of the EORTC QLQ-C30 at 6 and 14 months.

Data were sampled in identical ways irrespective of allocation status by use of patient questionnaires administered to patients alive at 6 and 14 months after inclusion. Non-responders were sent one reminder after 3 weeks.25

Sample size

The sample size was estimated based on the primary outcome measure. According to the EORTC Tables of Reference Values33 for all cancer patients, all stages, the Global Health Status is normally distributed with a mean of 61.3 and an SD of 24.2. A change of at least 8 units was assumed to be clinically relevant.33 34

If the lowest acceptable statistical power was 80%, then, based on the two-sample t test with a type 1 error α=0.05, the sample size was calculated to be 144 patients per group. The study was subject to clustering because the unit of randomisation was at the level of the GP, whereas the primary outcome measure was at the level of the patient. A strong effect on outcome of the individual practice was expected, but no data supported estimation of cluster effect. To allow maximum clustering, it was attempted to include patients to each group from a minimum of 144 practices.

Randomisation

Prior to study start, all 2181 general practices in Denmark were randomly allocated to the intervention (n=1091) or control (n=1090) group by the unique provider number of each practice using a computerised random-number generator in the statistical program Stata V.10.0 (StataCorp). Hence, randomisation was performed at practice level meaning that all GPs working under the same provider number were allocated to the same group. Consequently, spillover effect between GPs and patients from the same practice was minimised.

Blinding

The study was not blinded. The list of randomisation was available to the RCs during assessment of patient eligibility. Allocation status was obvious during intervention.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were described using descriptive statistics in order to present the distribution of age, sex and cancer type. We conducted intention to treat analyses, and numerical outcomes of the randomised controlled trial were analysed using a multilevel linear model, accounting for possible cluster effects caused by the cluster randomisation. All secondary outcomes were adjusted for confounding effect of age and sex. Missing values were regarded as missing at random. We conducted complete case analyses.

The statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.11.0 (StataCorp.).

Development and piloting of questionnaires and intervention

Before designing the intervention, we reviewed papers, reports and textbooks about the problems faced by cancer patients and GPs with respect to individual rehabilitation and continuity across healthcare sectors.1–3 16–24 35

The questionnaires and the procedures of identification, assessment and inclusion of patients were pilot tested prior to study start. The procedures have been described in detail.25

Results

In total, 955 patients fulfilled the criteria for inclusion and 486 patients were allocated to the intervention group and 469 to the control group (figure 1). The patients were registered with 323 general practices. Patients were on average aged 63 years at baseline and 72% were women. The most frequent cancer localisations were breast (43%) and lung (15%). The intervention and control groups showed similar baseline characteristics (table 2). For the primary outcome, Global Health Status at 6 months, we obtained data from 281 patients from 131 practices in the intervention group and 297 patients from 125 practices in the control group, in total 612 of 858 (71%) patients (95% CI for ICC 0.000 to 0.103). The percentage of missing data in the primary outcome was 5.6% (similar in the intervention and control groups).

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and medical characteristics for all included patients (n=955)

| Demographic characteristics | Control group (n=469) | Intervention group (n=486) |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (CI) | 63.6 (62.5 to 64.6) | 63.2 (62.2 to 64.3) |

| Median | 64 | 64 |

| Range | 21–98 | 28–92 |

| Sex | ||

| Male, n (%) | 134 (28.6) | 133 (27.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 335 (71.4) | 353 (72.6) |

| Cancer type | n (%) | n (%) |

| Cancer of breast | 206 (43.9) | 201 (41.4) |

| Cancer of lung | 69 (14.7) | 75 (15.4) |

| Malignant melanoma | 44 (9.4) | 35 (7.2) |

| Cancer of rectum/anus | 33 (7.0) | 45 (9.3) |

| Cancer of colon | 29 (6.2) | 39 (8.0) |

| Cancer of ovaries | 12 (2.6) | 9 (1.9) |

| Cancer of biliary system | 7 (1.5) | 8 (1.6) |

| Cancer of brain | 6 (1.3) | 8 (1.6) |

| Cancer of prostate | 8 (1.7) | 3 (0.6) |

| Cancer of corpus uteri | 6 (1.3) | 5 (1.0) |

| Myelomatosis | 6 (1.3) | 5 (1.0) |

| Lymphoma | 3 (0.6) | 4 (0.8) |

| Unspecified location | 16 (3.4) | 16 (3.3) |

| Other diagnoses | 24 (5.1) | 33 (6.8) |

The intervention had no statistically significant impact on the primary or on the secondary outcomes (tables 3 and 4). Adjustment for age and sex of the secondary outcomes showed results similar to the unadjusted analysis. Intention to treat analyses on all outcomes of the group of breast cancer patients showed no statistical differences between patients in the intervention and control groups (mean difference in primary outcome of 1.77 (−3.2 to 6.8)). Per-protocol analyses on all outcomes were used to analyse if the personal telephone contact to the GP was crucial. The patients receiving all elements of the intervention showed no statistically significant difference when compared with the control group (mean difference in primary outcome of −4.43 (−9.7 to 0.8)).

Table 3.

Health-related quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30) outcome variables and mean differences at 6 and 4 months (95% CI)

| Outcome variable | 6 months |

14 months |

||||||

| n | Mean (CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p Value | n | Mean (CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Global health status/quality of life | ||||||||

| Control group | 297 | 68.0 (65.5 to 70.5) | 246 | 72.8 (70.3 to 75.3) | ||||

| Intervention group | 281 | 69.3 (66.7 to 71.9) | 1.25 (−2.4 to 4.9) | 0.50 | 240 | 72.1 (69.6 to 74.7) | −0.71 (−4.3 to 2.8) | 0.69 |

| Physical functioning | ||||||||

| Control group | 294 | 79.0 (76.4 to 81.5) | 240 | 81.9 (79.3 to 84.5) | ||||

| Intervention group | 280 | 79.7 (77.1 to 82.4) | 0.77 (−2.9 to 4.4) | 0.68 | 234 | 82.0 (79.4 to 84.6) | −0.08 (−3.6 to 3.8) | 0.97 |

| Role functioning | ||||||||

| Control group | 291 | 71.3 (67.7 to 74.9) | 239 | 78.0 (74.4 to 81.7) | ||||

| Intervention group | 277 | 72.5 (68.8 to 76.1) | 1.18 (−3.9 to 6.3) | 0.65 | 235 | 78.8 (75.0 to 82.5) | 0.70 (−4.5 to 5.9) | 0.79 |

| Emotional functioning | ||||||||

| Control group | 293 | 80.5 (78.1 to 83.0) | 240 | 80.7 (77.9 to 83.4) | ||||

| Intervention group | 278 | 81.6 (79.1 to 84.1) | 1.02 (−2.5 to 4.5) | 0.57 | 238 | 80.8 (78.0 to 83.6) | 0.12 (−3.8 to 4.1) | 0.95 |

| Cognitive functioning | ||||||||

| Control group | 290 | 83.0 (80.5 to 85.5) | 245 | 82.6 (79.7 to 85.5) | ||||

| Intervention group | 278 | 83.9 (81.3 to 86.4) | 0.88 (−2.7 to 4.5) | 0.63 | 238 | 85.1 (82.1 to 88.2) | 2.53 (−1.7 to 6.7) | 0.24 |

| Social functioning | ||||||||

| Control group | 295 | 85.7 (83.0 to 88.4) | 242 | 88.2 (85.4 to 91.0) | ||||

| Intervention group | 280 | 86.0 (83.2 to 88.8) | 0.28 (−3.6 to 4.2) | 0.89 | 238 | 87.4 (84.6 to 90.3) | −0.77 (−4.8 to 3.2) | 0.71 |

| Fatigue | ||||||||

| Control group | 292 | 37.4 (34.3 to 40.6) | 244 | 32.1 (28.8 to 35.3) | ||||

| Intervention group | 279 | 34.2 (30.9 to 37.4) | −3.27 (−7.8 to 1.3) | 0.16 | 234 | 32.3 (28.9 to 35.6) | 0.23 (−4.5 to 4.9) | 0.92 |

| Nausea and vomiting | ||||||||

| Control group | 300 | 8.1 (6.1 to 10.0) | 244 | 5.5 (3.9 to 7.2) | ||||

| Intervention group | 284 | 8.0 (6.0 to 10.0) | −0.11 (−2.9 to 2.7) | 0.94 | 236 | 5.6 (3.9 to 7.3) | 0.05 (−2.3 to 2.4) | 0.97 |

| Pain | ||||||||

| Control group | 283 | 23.0 (19.8 to 20.2) | 241 | 21.9 (18.5 to 25.4) | ||||

| Intervention group | 274 | 22.0 (18.8 to 25.3) | −0.95 (−5.5 to 3.6) | 0.68 | 234 | 21.4 (17.8 to 24.9) | −0.56 (−5.5 to 4.4) | 0.83 |

| Dyspnoea | ||||||||

| Control group | 297 | 17.0 (13.9 to 20.2) | 245 | 13.2 (10.0 to 16.5) | ||||

| Intervention group | 286 | 17.9 (14.7 to 21.2) | 0.87 (−3.6 to 5.4) | 0.71 | 233 | 15.4 (11.9 to 18.8) | 2.11 (−2.6 to 6.8) | 0.38 |

| Insomnia | ||||||||

| Control group | 302 | 27.5 (24.0 to 31.0) | 248 | 29.6 (25.6 to 33.6) | ||||

| Intervention group | 285 | 27.3 (23.6 to 30.9) | −0.23 (−5.3 to 4.8) | 0.93 | 240 | 28.5 (24.4 to 32.6) | −1.08 (−6.8 to 4.6) | 0.71 |

| Appetite loss | ||||||||

| Control group | 301 | 14.1 (11.0 to 17.2) | 246 | 9.6 (7.1 to 12.2) | ||||

| Intervention group | 288 | 15.9 (12.7 to 19.0) | 1.79 (−2.7 to 6.2) | 0.43 | 239 | 7.9 (5.4 to 10.5) | −1.67 (−5.3 to 2.0) | 0.37 |

| Constipation | ||||||||

| Control group | 299 | 12.6 (9.7 to 15.5) | 248 | 11.9 (9.0 to 14.91) | ||||

| Intervention group | 284 | 11.3 (8.3 to 14.2) | −1.33 (−5.4 to 2.8) | 0.53 | 236 | 8.9 (5.9 to 11.9) | −3.03 (−5.5 to 2.8) | 0.16 |

| Diarrhoea | ||||||||

| Control group | 299 | 11.3 (8.8 to 13.9) | 250 | 11.4 (8.5 to 14.2) | ||||

| Intervention group | 284 | 11.4 (8.8 to 14.1) | 0.08 (−3.6 to 3.8) | 0.97 | 238 | 10.0 (7.0 to 13.0) | −1.38 (−5.5 to 2.8) | 0.51 |

| Financial difficulties | ||||||||

| Control group | 297 | 7.6 (5.4 to 9.8) | 242 | 6.5 (3.9 to 9.0) | ||||

| Intervention group | 284 | 8.0 (5.7 to 10.2) | 0.34 (−2.8 to 3.5) | 0.83 | 236 | 6.7 (4.1 to 9.4) | 0.27 (−3.4 to 4.0) | 0.89 |

Mean values from 0 to 100. A score of 100 indicates optimal function or maximum symptom intensity (ie, for functional measures, an increase indicates improvement, while for symptoms, an increase indicates worsening).

EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30.

Table 4.

Psychological distress (POMS) at 14 months and mean differences between groups (95 CI%)

| Outcome variable | n | Mean range | Mean (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p Value |

| Anger/hostility | 0–28 | ||||

| Control group | 223 | 2.03 (1.59 to 2.48) | |||

| Intervention group | 230 | 1.88 (1.43 to 2.33) | −0.15 (−0.79 to 0.48) | 0.64 | |

| Confusion/bewilderment | 0–20 | ||||

| Control group | 229 | 2.45 (2.04 to 2.86) | |||

| Intervention group | 231 | 2.11 (1.69 to 2.53) | −0.34 (−0.92 to 0.25) | 0.26 | |

| Depression/dejection | 0–32 | ||||

| Control group | 223 | 3.85 (3.20 to 4.51) | |||

| Intervention group | 229 | 3.26 (2.61 to 3.92) | −0.59 (−1.52 to 0.34) | 0.21 | |

| Fatigue/inertia | 0–20 | ||||

| Control group | 226 | 4.65 (4.08 to 5.22) | |||

| Intervention group | 234 | 4.14 (3.02 to 4.10) | −0.51 (−1.32 to 0.29) | 0.21 | |

| Tension/anxiety | 0–24 | ||||

| Control group | 226 | 3.82 (3.28 to 4.36) | |||

| Intervention group | 233 | 3.56 (3.02 to 4.10) | −0.26 (−1.02 to 0.50) | 0.50 | |

| Vigour/activity | 0–24 | ||||

| Control group | 218 | 10.28 (9.51 to 11.05) | |||

| Intervention group | 228 | 10.09 (9.31 to 10.86) | −0.20 (−1.29 to 0.89) | 0.72 | |

| Total mood disturbance | 0–124 | ||||

| Control group | 200 | 4.87 (2.29 to 7.45) | |||

| Intervention group | 210 | 4.19 (1.62 to 6.76) | −0.68 (−4.32 to 2.97) | 0.72 |

Mean values of each subscale depends on the number of items related to the individual subscale which varies from 5 to 8, each item ranging from 0 to 4. Total mood disturbance is calculated by summing up the scores on the five negative symptom subscales and subtracting the score on the one positively scored subscale, vigour/activity. A higher score indicates a higher degree of symptoms/feelings within the related subscale.

POMS, Profile of Mood States.

Discussion

Principal findings

This intervention including a hospital-based patient interview about rehabilitation, individual and general information to the GP and an encouragement to contact the patient and facilitate a process of rehabilitation did not improve quality of life or relieve psychological distress of patients newly diagnosed as having cancer.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The study included 955 patients and the pre-study power calculation and the precision of the statistical estimates indicate that the study could have detected relevant effects of the intervention. The CI of the difference in global health status after 6 months ranged between −2.4 and 4.9 units. Clinically relevant differences have been suggested to correspond to at least 8 units.33 34

An important question is whether any spillover effects may have improved care for the patients in the control group, leading to an apparently smaller impact of the intervention. Information about the study and the concept of rehabilitation was given to the staff at the involved departments at Vejle Hospital during the inclusion period, but the intervention was managed by the two rehabilitation coordinators without influence on the care provided for the patients in the control group. The cluster randomisation was performed to ensure that GPs only cared for patients in either the intervention or the control group. GPs in the control group were not informed about the study, and we have no reason to believe that information about the study was disseminated between GPs in the two groups.

Another question is whether we used the most relevant outcome measures. Process measures are often used to evaluate interventions. However, despite successful implementation of interventions, the impact on patients' well-being is often sparse. Hence, we deliberately chose patients' quality of life as the primary outcome. Furthermore, the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the Profile of Mood States questionnaires are well-validated instruments to evaluate change of quality of life in cancer patients and psychological distress in general.30–34

The intervention was designed to support rehabilitation irrespective of the character of the problem, cancer type, age and sex. We included patients with various cancer types, different prognosis, health problems and needs of supportive care. The inhomogeneity of the study population might have diluted effects in groups of patients with specific problems or diagnoses. It cannot be ruled out that a similar intervention might have effect on subgroups of patients with specific cancers or special needs. However, no effect was observed when analysing the large and rather homogeneous group of breast cancer patients.

The intervention included a personal telephone contact to the patients' GP but some GPs were not reachable.25 A priori we assumed that this personal contact could be of major importance, but per-protocol analysis showed no differences in outcomes for patients where the rehabilitation coordinators managed to reach the GP by phone.

Relations to other studies

To our knowledge, only three papers have specifically evaluated the impact of GP involvement in cancer rehabilitation in a randomised design.17 35 36 A shared care programme (n=250) conducted in Denmark in 2003 included transfer of knowledge from oncologists to GPs, improved communication between parties and active patient involvement.17 This intervention had a positive impact on patient evaluation of cooperation between primary and secondary healthcare sectors but not on quality of life. A Norwegian study from 2005 (n=91) evaluated the effect of an invitation to a 30 min consultation with the patient's GP, aiming at creating a closer and more frequent contact between patients and GPs.35 No increase in number of consultations or improvement of quality of life was observed. The latest study was conducted in Sweden in 2008 (n=481) and tested the effectiveness of individual support, group rehabilitation and a combination of the two compared with standard care.36 The individual support included individual psychological and nutritional support along with intensified primary healthcare, including extended information about the diagnosis, education in cancer care and supervision of the patient's home care nurse and GP by a multiprofessional oncology team. The Swedish study did not show an improvement either in quality of life or psychological well-being when compared with standard care. Furthermore, a systematic review37 including the three studies concluded that none of the interventions improved quality of life or patient well-being, but due to possible methodological problems, further studies on the topic are needed.

Meaning

Interventions aiming to give the GP an enhanced role in cancer rehabilitation seem to have difficulties improving quality of life. Furthermore, a number of papers evaluating the effect of various other types of interventions aiming to improve quality of life of cancer patients38–43 have demonstrated that this may be difficult in general. To better understand the intervention and the impact on GP and patient behaviour, further studies will include evaluation of process measures like GP proactivity, patient participation in different rehabilitation activities and GP and patient satisfaction.

Future studies should evaluate the importance of the organisation of cancer treatment and rehabilitation. Is an unclear organisation with many partners (hospital departments, GPs, municipalities and private organisations) an impediment to effective rehabilitation? A well-organised system with defined roles and easy referral to various elements of rehabilitation (specialised physiotherapy, social counselling, psychological advice etc.) may be of importance for the effect of a GP intervention. To improve rehabilitation, it may also be important to develop screening tools that support identification of patients with special needs. Initiatives supporting the GPs in undertaking a proactive role for patients with special needs should be considered. The effect of interventions should, however, be carefully evaluated in order to ensure efficient use of resources before implementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all patients and healthcare professionals who took part in the study. We also wish to thank Lise Keller Stark, Research Unit of General Practice, University of Southern Denmark, for proofreading the manuscript and Susanne Døssing Berntsen for managing data sets.

Footnotes

To cite: Bergholdt SH, Larsen PV, Kragstrup J, et al. Enhanced involvement of general practitioners in cancer rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000764. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000764

Contributors: SHB, JK, JS and DGH contributed to conception and study design. SHB, DGH, JK and JS obtained the funding. SHB, JK, JS and DGH wrote the protocol. SHB and DGH were responsible for recruitment of patients. SHB collected and managed the data. PVL was the study statistician. SHB and PVL performed the statistical analysis. SHB, PVL, JK, JS and DGH contributed to the interpretation of data. SHB drafted the first version of the manuscript. SHB, JK, JS, PVL and DGH critically reviewed, revised and supplemented the manuscript. All authors approved the final version. SHB is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the Danish Cancer Society, the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Region of Southern Denmark. The National Research Center for Cancer Rehabilitation is funded by the Danish Cancer Society.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics evaluated the project and concluded that the intervention did not need an approval from the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics according to Danish law (Project-ID: S-20082000-7).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Mikkelsen TH, Sondergaard J, Jensen AB, et al. Cancer rehabilitation: psychosocial rehabilitation needs after discharge from hospital? Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:216–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Comittee on Cancer Survivorship. Improving Care and Quality of Life, National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine, and National Research COUNCIL. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groenvold M, Pedersen C, Jensen CR, et al. The Cancer Patient's World- an Investigation of the Problems Experienced by Danish Cancer Patients. Copenhagen: Danish Cancer Society, 2006. [in Danish]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid-Buchi S, Halfens RJ, Dassen T, et al. Psychosocial problems and needs of posttreatment patients with breast cancer and their relatives. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2011;15:260–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steele R, Fitch MI. Supportive care needs of patients with lung cancer. Can Oncol Nurs J 2010;20:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele R, Fitch MI. Supportive care needs of women with gynaecological cancer. Cancer Nurs 2008;31:284–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, et al. Patients' supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6172–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDowell ME, Occhipinti S, Ferguson M, et al. Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19:508–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organisation http://www.who.int/topics/rehabilitation/en (accessed 18 Nov 2011).

- 10.Jones R, Regan M, Ristevski E, et al. Patients' perception of communication with clinicians during screening and discussion of cancer supportive care needs. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:e209–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5112–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert SM, Miller DC, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Cancer survivorship: challenges and changing paradigms. J Urol 2008;179:431–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houlihan NG. Transitioning to cancer survivorship: plans of care. Oncology 2009;23(8 Suppl):42–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olesen F, Dickinson J, Hjortdahl P. General practice—time for a new definition. BMJ 2000;320:354–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: treatment through survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010;2010:25–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SM, Allwright S, O'Dowd T. Does sharing care across the primary-specialty interface improve outcomes in chronic disease? A systematic review. Am J Manag Care 2008;14:213–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen JD, Palshof T, Mainz J, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a shared care programme for newly referred cancer patients: bridging the gap between general practice and hospital. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:263–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunfeld E. Primary care physicians and oncologists are players on the same team. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2246–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grunfeld E. Cancer survivorship: a challenge for primary care physicians. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:741–2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson B, Berglund G, Hoffman K, et al. The role of the general practitioner in cancer care and the effect of an extended information routine. Scand J Prim Health Care 2000;18:143–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendall M, Boyd K, Campbell C, et al. How do people with cancer wish to be cared for in primary care? Serial discussion groups of patients and carers. Fam Pract 2006;23:644–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anvik T, Holtedahl KA, Mikalsen H. “When patients have cancer, they stop seeing me”–the role of the general practitioner in early follow-up of patients with cancer–a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulsara C, Ward AM, Joske D. Patient perceptions of the GP role in cancer management. Aust Fam Physician 2005;34:299–300, 302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikkelsen TH. PhD-thesis: Cancer rehabilitation in Denmark—With Particular Focus on the Present and Future Role of General Practice. Denmark: Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Aarhus, 2009. ISBN 978-87-90004-09-5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen DG, Bergholdt SH, Holm L, et al. A complex intervention to enhance the involvement of general practitioners in cancer rehabilitation. Protocol for a randomised controlled trial and feasibility study of a multimodal intervention. Acta Oncol 2011;50:299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. 2009 http://www.regionsyddanmark.dk [Google Scholar]

- 27.PLO Praksistælling [General Practitioners' Organisation Practice Count]. Copenhagen: PLO [General Practitioners' Organisation], 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ 1996;30:83–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mikkelsen T, Sondergaard J, Sokolowski I, et al. Cancer survivors' rehabilitation needs in a primary health care context. Fam Pract 2009;26:221–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groenvold M, Klee MC, Sprangers MA, et al. Validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire through combined qualitative and quantitative assessment of patient-observer agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:441–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker F, Denniston M, Zabora J, et al. A POMS short form for cancer patients: psychometric and structural evaluation. Psycho-Oncology 2002;11:273–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values Manual. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Brussels: EORTC, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol 2010;29;89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holtedahl K, Norum J, Anvik T, et al. Do cancer patients benefit from short-term contact with a general practitioner following cancer treatment? A randomised, controlled study. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:949–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson B, Brandberg Y, Hellbom M, et al. Health-related quality of life and distress in cancer patients: results from a large randomised study. Br J Cancer 2008;99:1975–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis RA, Neal RD, Williams NH, et al. Follow-up of cancer in primary care versus secondary care: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:e234–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aranda S, Schofield P, Weih L, et al. Meeting the support and information needs of women with advanced breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 2006;95:667–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rottmann N, Dalton SO, Bidstrup PE, et al. No improvement in distress and quality of life following psychosocial cancer rehabilitation. A randomised trial. Psychooncology. Published Online First: 8 February 2011. doi:10.1002/pon.1924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross L, Boesen EH, Dalton SO, et al. Mind and cancer: does psychosocial intervention improve survival and psychological well-being? Eur J Cancer 2002;38;1447–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fors EA, Bertheussen GF, Thune I, et al. Psychosocial interventions as part of breast cancer rehabilitation programs? Results from a systematic review. Psychooncology 2010;20:909–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newell SA, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer Patients: overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:558–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uitterhoeve RJ, Vernooy M, Litjens M, et al. Psychosocial interventions for patients with advanced cancer—a systematic review of the literature. Br J Cancer 2004;91:1050–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.