Abstract

Objectives

Data linkage combines information from several clinical data sets. The authors examined whether coding inconsistencies for cardiovascular disease between components of linked data sets result in differences in apparent population characteristics.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Routine primary care data from 40 Scottish general practitioner (GP) surgeries linked to national hospital records.

Participants

240 846 patients, aged 20 years or older, registered at a GP surgery.

Outcomes

Cases of myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease and stroke (cerebrovascular disease) were identified from GP and hospital records. Patient characteristics and incidence rates were assessed for all three clinical outcomes, based on GP, hospital, paired GP/hospital (similar diagnoses recorded simultaneously in both data sets) or pooled GP/hospital records (diagnosis recorded in either or both data sets).

Results

For all three outcomes, the authors found evidence (p<0.05) of different characteristics when using different methods of case identification. Prescribing of cardiovascular medicines for ischaemic heart disease was greatest for cases identified using paired records (p≤0.013). For all conditions, 30-day case fatality rates were higher for cases identified using hospital compared with GP or paired data, most noticeably for myocardial infarction (hospital 20%, GP 4%, p=0.001). Incidence rates were highest using pooled GP/hospital data and lowest using paired data.

Conclusions

Differences exist in patient characteristics and disease incidence for cardiovascular conditions, depending on the data source. This has implications for studies using routine clinical data.

Article summary

Article focus

Data linkage allows information to be combined from different routine clinical data sources.

Previous work has shown differences between sources of data but has not examined this at the patient level.

Key messages

Patients' apparent characteristics, and disease incidence and severity, vary depending on whether primary care, hospital or combined definitions of cardiovascular events are used.

Use of isolated routine primary care or hospital data may result in biased patient selection.

This has implications in the public health arena, clinical trial patient recruitment and validity and reliability of secondary data in clinical trials.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strengths of this study are the novel analytical approach, using a large routine data set linked at individual patient level from multiple GP surgeries.

Limitations of this study include restricting our analysis to four coding groups, uncertainty as to whether GP and hospital events could be considered to be recorded simultaneously, potential diagnostic coding inaccuracies and the relatively small number of GP surgeries, which may not have been representative.

Background

Primary care data sets are commonly used for assessment of cardiovascular outcomes. Such events often are associated with hospitalisation.1 However, it is possible that the manner in which outcomes are coded and recorded in electronic health records may differ between primary and secondary care. This may result not only in differences in the apparent incidence of a condition, depending on whether primary or secondary care records are used, but also in differences in the observed characteristics of patients. Studies have observed that variations in diagnostic criteria can affect estimates of disease prevalence,2 and the complexities of clinical coding systems for electronic healthcare records can lead to inconsistent data recording.3 This will lead to uncertainties with respect to disease prevalence and mortality,4 impact on clinical care, have additional health service implications such as affecting funding5 and potentially influence identification of patients for clinical trials. Previous studies have compared general practice coding and disease prevalence with other unlinked data sources, including paper notes.6 7 However, the effect of combining information from two sources has not been previously examined. This study used linked individual patient electronic health records collected from primary and secondary care to examine the effect of using data from different parts of the healthcare service on the incidence rates, case fatality rates and patient characteristics of myocardial infarction (MI), ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and cerebrovascular disease (CVD).

Methods

Data sources

Sixty general practitioner (GP) surgeries take part in the Scottish national Practice Team Information (PTI) project, of which 40 self-selected surgeries contributed to the data set used in this study. Practices involved in the PTI project provide routine central recording of clinical activity and morbidity from a sample of GP surgeries considered reasonably representative of the Scottish population. Practices are reimbursed to ensure that data recording is optimal. Clinical coding used the Read code system. Data are used to calculate national estimates and used by various organisations (eg, NHS Boards, Scottish Government) to inform policies and better understand health in Scotland.

Patient details from the PTI data set were linked to the corresponding admissions recorded in Scottish national hospital data (the Scottish Morbidity Record, SMR-01) using probabilistic matching. Matching was based on Soundex-encoded name, date of birth, sex, postcode and a unique nationwide identifier, the Community Health Index. Experienced human review was used to set a threshold for linkage. A substantial proportion of patients in this GP cohort have no hospital admissions, and as such, it is difficult to know whether the absence of a match is either due to a genuine lack of corresponding hospital record or due to a false-negative error. Match rates are thus difficult to quantify, although the use of multiple identifiers should improve linkage quality. The linkage was carried out by the Information Services Division, NHS National Services Scotland. The work was approved by the Privacy Advisory Committee of NHS National Services Scotland. For the 2004–2006 period, SMR-01 data are considered to be 88% accurate.8 SMR-01 records are generated for all inpatient hospital medical discharges and transfers. Coding is based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) system (ICD9 prior to 2000, ICD10 thereafter), with up to six inpatient diagnoses per record. Accident and emergency, maternity and psychiatric admissions, along with outpatient attendances, are not recorded in SMR-01. SMR-01 itself is also routinely linked to national mortality data (General Registrar's Office for Scotland, GROS). SMR-GROS data are also used to generate Scottish National Statistics.

Identification and classification of cases

We first identified all records of MI, IHD and CVD from both GP and hospital data sets using the following Read codes (MI: G30%/35%/38%, Gyu34/35/36; IHD: G3%, Gyu3%; CVD: G6%, Gyu6%, F4236; where % indicates a ‘wildcard’ match) and ICD codes (MI: ICD10 I21–22, ICD9 410; IHD including MI: ICD10 I20–25, ICD9 410–414; CVD (stroke) including haemorrhage and transient ischaemic attack (TIA): ICD10 I60–69, G45–46; ICD9 430–438). Hospital events were identified from any of the six diagnostic positions. These were not necessarily first events.

We then found all episodes of a similar GP and hospital event type occurring within a 30-day period and made the assumption that these pairings represented the same clinical event. Where the GP and hospital dates differed for these paired episodes, the first of the two dates was taken. The choice of 30 days was a pragmatic one but supported by visual evaluation of the distribution of time gaps between similar hospital and GP event types over a 2-year period. Of note, an event recorded by the GP does not necessarily require a face-to-face consultation or a referral to be made; hospital admissions will usually be retrospectively recorded by the GP, using the admission date as opposed to the data-entry date.

Analysis was carried out over the period 1 January 2005 to 1 January 2007. The total population was randomly allocated to one of four methods of identifying cardiovascular events: those based on GP events only; those based on hospital events only; those based on pooled GP/hospital events, with an event in GP data only, hospital data only or both the GP and hospital data (although not necessarily occurring within 30 days); and those based on paired GP/hospital events (those recorded in both GP and hospital data within 30 days). An episode was included as an incident event only if there was no record of a similar clinical event at any time prior to 1 January 2005 coded in the same data set(s).

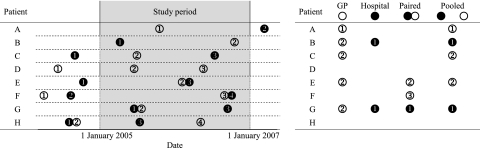

This method of identifying incident events is shown in figure 1. For example, for an event to be included using only GP data, the first event would have to be recorded by the GP during the 2-year period of interest, with no similar events recorded by the GP prior to 1 January 2005; hospital data are completely ignored in this case. A similar approach is used for identifying events using hospital-only data, with GP records ignored in this situation. For the third method, identifying events using pooled GP/hospital data, the first event needs to be recorded by either the hospital or the GP during the 2-year study period; there must be no similar event recorded in either data set prior to 1 January 2005. For the final method, the first occurrence of paired (ie, within 30 days) records in both GP and hospital data sets constituted an incident event if it occurred during the 2-year period; any unpaired GP or hospital records occurring prior to 1 January 2005 were ignored.

Figure 1.

Identification of incident events. The figure shows how incident events can be identified from linked general practice (GP) and hospital data sets, for eight hypothetical patients, illustrating some of the potential coding combinations. Circles correspond to the presence of a GP (○) or hospital (●) clinical code, with numbers illustrating the order. Immediately adjacent circles represent codes occurring within 30 days of one another. It can be seen that, for any given patient, it is possible to classify them as having an incident event in up to four ways: GP data only, hospital data only, paired GP/hospital and pooled GP/hospital; the code that identifies an incident event for each of these methods is shown on the right of the figure. Codes do not count as incident events if a further, similarly classified, event has occurred prior to the start of the study period. In our study, patients were randomly allocated to one of the four coding methods. For instance, if patient E was allocated to ‘hospital only’ coding, they would not be classified as having had an event; in contrast, they would be classified as having had an event if they were allocated to any of the other three coding methods.

For each incident event, we determined the patient's age, sex, socioeconomic status (Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile),9 recorded current smoking status, record of hypertension, record of diabetes and Charlson Index.10 Comorbidities, including Charlson Index, were determined from the GP data as the presence of any relevant diagnostic Read code prior to the incident episode date; the list of codes used is available from the authors on request. Although we have not formally evaluated performance of our Charlson Index Read code list, we match 87% of those events identified by the method described by Khan et al,11 and as such believe that this represents a reasonable, albeit pragmatic, measure of comorbidity. Death from any cause within 30 days of the event was ascertained from linked national mortality (GROS) data. Drug therapy recorded in the GP record, starting prior to or within 30 days after the event, and continuing for any period of time after the event, was ascertained for patients alive at 30 days. Drug classes included were ACE inhibitors (including angiotensin receptor blockers), β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics (including potassium sparing and combination diuretics), nitrates, statins and antiplatelet agents (aspirin or clopidogrel for MI or IHD; aspirin or dipyridamole for CVD).

Statistical analysis

Incidence rates were calculated excluding patients with events in the relevant data set(s) prior to 1 January 2005. Incidence rates are expressed per 100 000 patient-years (based on total number of days of follow-up for each patient within each respective group). Statistical differences in patient characteristics (including drug treatment) between coding categories were evaluated using χ2 tests (for proportions) and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric analysis of variance (for continuous data). The association between coding and 30-day case fatality was assessed by logistic regression, including the covariates age, sex, deprivation, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes and Charlson Index. Differences in the four incident rates obtained were examined using Poisson regression.

Data management was carried out using Microsoft SQL Server 2000. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.17 (SPSS Inc.).

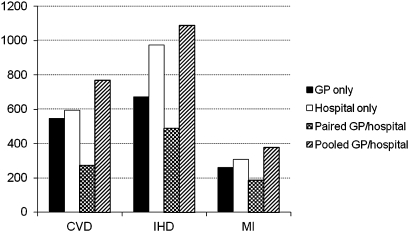

Results

Differences in identification of incidence events

There were a total of 240 846 patients, evenly distributed between the four coding groups. Numbers of incident events are shown in table 1. Incidence rates for the three conditions are shown in figure 2. There was strong evidence (p<0.001, Poisson regression) that the incidence rates for all three clinical conditions depends on which data set(s) are used to identify cases. In all cases, the pooled GP/hospital data produced the highest incidence rates (376, 1089 and 767 per 100 000 patient-years for MI, IHD and CVD, respectively), and the paired GP/hospital data gave the lowest incidence rates (188, 489 and 272 per 100 000 patient-years, respectively). There was no evidence that the incidence rates based on only GP data differ from those of the hospital data for either MI (p=0.14) or CVD (p=0.27), but there was strong evidence that they were higher for IHD (975 and 673 events per 100 000 patient-years for hospital and GP, respectively, p<0.001). The pooled GP/hospital data produced slightly higher incidence rates than hospital data alone for CVD (p<0.001) and marginally so for MI (p=0.048) and IHD (p=0.066).

Table 1.

Variation of patient characteristics with different methods of identifying cases

| GP | Hospital | Paired GP/hospital | Pooled GP/hospital | p Value | |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| N | 145 | 171 | 105 | 209 | |

| Men (%) | 65 | 59 | 60 | 64 | 0.68 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 68 (13.8) | 67 (13) | 68.4 (13.8) | 68.8 (14.9) | 0.51 |

| Deprivation quintile (%) | |||||

| 1 | 19 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 0.55 |

| 2 | 15 | 25 | 26 | 17 | |

| 3 | 26 | 17 | 29 | 31 | |

| 4 | 15 | 23 | 21 | 22 | |

| 5 | 24 | 24 | 14 | 17 | |

| Smokers (%) | 33 | 34 | 45 | 28 | 0.028 |

| Diabetes (%) | 15 | 12 | 8 | 11 | 0.29 |

| Hypertension (%) | 39 | 44 | 38 | 44 | 0.52 |

| Charlson Index, mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||||

| N | 362 | 529 | 270 | 585 | |

| Men (%) | 56 | 55 | 61 | 56 | 0.38 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 66.2 (12.7) | 65.8 (11.6) | 66.9 (13.4) | 68.4 (12.8) | 0.007 |

| Deprivation quintile (%) | |||||

| 1 | 17 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 0.25 |

| 2 | 18 | 20 | 20 | 21 | |

| 3 | 29 | 23 | 27 | 26 | |

| 4 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 20 | |

| 5 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 19 | |

| Smokers (%) | 27 | 27 | 35 | 24 | 0.011 |

| Diabetes (%) | 11 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 0.091 |

| Hypertension (%) | 42 | 47 | 44 | 45 | 0.51 |

| Charlson Index, mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.5) | 0.002 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||||

| N | 302 | 330 | 153 | 424 | |

| Men (%) | 48 | 47 | 46 | 47 | 0.97 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 70.3 (14.1) | 70.8 (13.6) | 72 (12.9) | 73 (13.6) | 0.031 |

| Deprivation quintile (%) | |||||

| 1 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 11.6 | 0.72 |

| 2 | 23 | 18 | 22 | 19.1 | |

| 3 | 29 | 29 | 32 | 23.6 | |

| 4 | 24 | 22 | 24 | 23.3 | |

| 5 | 15 | 20 | 14 | 22.3 | |

| Smokers (%) | 26 | 28 | 29 | 25 | 0.68 |

| Diabetes (%) | 13 | 16 | 13 | 13 | 0.47 |

| Hypertension (%) | 46 | 49 | 53 | 46 | 0.40 |

| Charlson Index, mean (SD) | 2 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.7) | 1.9 (1.6) | 2.1 (1.7) | 0.014 |

Patient characteristics for myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, identified using GP, hospital, paired GP/hospital and pooled GP/hospital data. Deprivation quintile 1 is least deprived. Significant differences are calculated by χ2 test or Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance.

GP, general practitioner.

Figure 2.

Incidence rates, expressed per 100 000 patient-years, for different clinical conditions over a 2-year time period beginning 1 January 2005, based on general practice (GP), hospital, paired GP/hospital and pooled GP/hospital data. CVD, cerebrovascular disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in table 1 for all three clinical conditions. There was no evidence that rates of diabetes and hypertension, or the distribution of sex or deprivation, varied between coding groups. Greater numbers of smokers were found in the paired GP/hospital group for patients with MI (45% in the paired group compared with 28%–34% in the other groups, p=0.028) and IHD (35% compared with 24%–27%, p=0.021). The level of comorbidity for all conditions, as measured by the Charlson Index, is lower in the paired GP/hospital group (1.8, 1.3 and 1.9 for MI, IHD and CVD, respectively) and higher in the hospital group (2.2, 1.7 and 2.4, respectively, p≤0.014). For IHD and CVD, there is evidence that patients identified using solely GP or solely hospital data were slightly younger.

Prescribing

Differences in prescribing rates were observed between coding groups (table 2). These were most marked for IHD, where rates of prescribing of ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, nitrates, statins and antiplatelet agents were higher in the paired group (p≤0.013). However, this finding did not appear to be replicated for MI specifically. For CVD, prescribing rates for statins and antiplatelet agents were lower in the hospital group (p≤0.022).

Table 2.

Variation of patient characteristics with different methods of identifying cases

| GP | Hospital | Paired GP/hospital | Pooled GP/hospital | p Value | |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| N | 139 | 137 | 99 | 173 | |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB (%) | 68 | 77 | 77 | 71 | 0.30 |

| β-blocker (%) | 68 | 61 | 59 | 61 | 0.50 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%) | 10 | 10 | 8 | 15 | 0.29 |

| Diuretic (%) | 32 | 32 | 28 | 29 | 0.87 |

| Nitrate (%) | 46 | 61 | 59 | 55 | 0.065 |

| Statin (%) | 79 | 81 | 77 | 76 | 0.70 |

| Antiplatelet agent (%) | 84 | 82 | 85 | 78 | 0.43 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||||

| N | 353 | 484 | 262 | 541 | |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB (%) | 48 | 48 | 58 | 45 | 0.013 |

| β-blocker (%) | 57 | 54 | 62 | 49 | 0.005 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%) | 21 | 21 | 25 | 19 | 0.28 |

| Diuretic (%) | 35 | 30 | 34 | 33 | 0.57 |

| Nitrate (%) | 40 | 43 | 60 | 40 | <0.001 |

| Statin (%) | 67 | 67 | 82 | 63 | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet agent (%) | 71 | 71 | 87 | 66 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||||

| N | 285 | 278 | 145 | 381 | |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB (%) | 38 | 33 | 31 | 36 | 0.42 |

| β-blocker (%) | 25 | 19 | 22 | 19 | 0.16 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%) | 20 | 15 | 13 | 17 | 0.27 |

| Diuretic (%) | 32 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 0.99 |

| Nitrate (%) | 15 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 0.94 |

| Statin (%) | 56 | 41 | 53 | 50 | 0.006 |

| Antiplatelet agent (%) | 54 | 44 | 50 | 55 | 0.022 |

The 30-day prescribing rates for myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, identified using GP, hospital, paired GP/hospital and pooled GP/hospital data. Patients are those alive at 30 days, and this is reflected by lower numbers of patients than in tables 1 and 3. Significant differences are calculated by χ2 test.

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; GP, general practitioner.

case fatality

Considerable 30-day case fatality rate differences exist for all three conditions depending on the coding used (p≤0.002, table 3). Rates for all conditions are highest in patients coded only in hospital and lower in the GP and paired GP/hospital groups. The most striking differences were observed for MI, with a 30-day case fatality rate of 20% for the hospital group but only 4% for the GP group.

Table 3.

Variation of case fatality rates with different methods of identifying cases

| GP | Hospital | Paired GP/hospital | Pooled GP/hospital | p Value | |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| N | 145 | 171 | 105 | 209 | |

| 30-day case fatality rate (%) | 4 | 20 | 6 | 17 | 0.001 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||||

| N | 362 | 529 | 270 | 585 | |

| 30-day case fatality rate (%) | 2 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 0.002 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||||

| N | 302 | 330 | 153 | 424 | |

| 30-day case fatality rate (%) | 6 | 16 | 5 | 10 | 0.001 |

The 30-day case fatality rates for myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, identified using GP, hospital, paired GP/hospital and pooled GP/hospital data. The significance of the differences between coding methods is adjusted for confounding factors using logistic regression (see text for details).

GP, general practitioner.

Discussion

In a world where electronic healthcare data are becoming increasingly used for the purposes of clinical trials and epidemiological research, there is a need for researchers to understand whether additional information can be gained by linking two (or indeed more) electronic health record data sources together. However, where there is overlap between the constituent data sets, such as with coding of clinical conditions, the researcher needs to decide which data set to rely on for identifying cases, or indeed whether combining information from both the data sets may be of value. Our study demonstrates that the method of coding MI, IHD and CVD appears to result in identification of different types of patient, in particular as characterised by prescribing and case fatality rates. Incident rates of disease also vary depending on the coding method used.

Previous work examining the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease has been conducted in Scotland using routine clinical data. Primary care data have been used to demonstrate that IHD is a common problem associated with male gender, increasing age and socioeconomic deprivation.12 Yet the recording of IHD data varies in general practice with different methods used for case detection.13 Furthermore, external factors such as payment-for-performance have been shown to improve the recording of IHD-related health indicators.14 Such incentivisation was introduced to UK general practice (but not hospital practice) in 2004, and so it is possible that this may have reduced the discrepancies between hospital and GP data in our study. Interestingly, pooling of GP and SMR records has previously been advocated for detecting MI cases,15 and pooled GP/SMR data from the same data set we used have demonstrated differences between cohorts of incident and prevalent MI.16 However, the effect of using only one component of such a data set has been hitherto unknown.

Reasons for differences in incidence rates and patient characteristics

Our data do not allow us to determine the exact cause of our findings, but a number of hypotheses may be proposed. Incident disease is reassuringly similar between GP and hospital groups for MI and CVD. The lower incidence of IHD for the GP group reflects the fact that many patients will have had relatively stable coronary disease for a number of years but not necessarily required acute hospital admission. Thus, many GP episodes of IHD do not count as true incident cases as they have had prior contact with the GP, whereas a higher number of hospital episodes are incident cases as these patients have never been previously admitted. The lower incidence rates for the paired GP/hospital group, and higher incidence rates for the pooled GP/hospital group, are inevitable consequences of the way in which the two data sets are united, although the magnitude of these differences will nonetheless reflect the degree of inconsistency in coding between the two. Furthermore, it would appear that because the paired GP/hospital data considerably underestimate the true disease incidence, it is probably not a useful method for identifying cases, even though such cases might be more rigorously identified. In addition, the increase in incidence rate using the pooled GP/hospital data demonstrates the potential advantage of combining two data sets, over use of a single data set, from the perspective of improving case finding.

The discrepancies in death rates are probably relatively straightforward to explain. Acute MI admission has a high case fatality,1 but those surviving beyond discharge have a much lower case fatality subsequently. It seems likely that the GP may fail to record the cause of death in patients who do not survive the hospital admission, thus resulting in the lower case fatality rates observed in the paired GP/hospital coding group. Furthermore, it is possible that patients coded only by the GP may represent ‘less serious’ illness, where hospitalisation is not deemed necessary by the GP. It is recognised that many patients suffering relatively minor strokes may not be admitted to hospital,17 resulting in lower case fatality for CVD in the GP group, although with the growing availability of active treatment options for ischaemic stroke in the form of thrombolysis, this may well change. We used national mortality data to identify deaths from both GP and SMR data sets, so discrepancies in recording of death between GP and hospital are unlikely to explain the differences in case fatality rates observed. Furthermore, the majority of paired events share exactly the same date, suggesting that retrospective date entry by the GP of the hospital event is common, and thus, there is no reason why this could not be carried out for fatal events.

The higher prescribing rates for IHD in the paired coding group are probably due to GPs responding appropriately to secondary care instigated intervention, reflected in appropriate treatment. That such differences were not observed for MI may be due to better communication and awareness for this specific condition compared with other IHD, such as angina, meaning that prescribing in the hospital group appears just as good as for the paired GP/hospital group. However, fewer MI events may have left us underpowered to detect differences. The lack of difference in the GP and paired groups for CVD may reflect poorer awareness of stroke management guidelines18 in comparison with coronary heart disease, and so prescribing rates are consequently no higher in the paired group. The lower prescribing rates of statins and antiplatelet agents in the CVD hospital group may reflect the GP being unaware of these patients' clinical need resulting in undertreatment; this is supported by the higher prescribing rates in the paired group. The differences in other patient characteristics—specifically smoking and comorbidity—are less easy to understand but may represent increased disease severity and mortality in hospitalised smokers and multimorbid patients. The small differences in age (<3 years) seem unlikely to be clinically relevant, although may be pertinent from the public health perspective. Finally, it may be that miscoding of diagnoses may explain some of the above differences; for instance, heart failure may be used as an alternative but incorrect code for MI.19 Furthermore, the introduction of sensitive troponin assays has influenced MI detection rates20; it is possible that lack of familiarity among some clinicians for the resulting terms (eg, non-ST elevation MI, acute coronary syndrome) may result in inaccurate diagnoses being recorded.

Limitations

This study has highlighted important issues related to patient coding and linked data, but although it has the advantage of using a reasonably large routine data set, linked at the individual patient level, a number of issues and limitations should be considered. The relatively small number of GP surgeries (40) may not have been fully representative. In addition, the number of events is relatively small, and given the conservative nature of the χ2 test, this increases the possibility of type 2 errors; thus, a larger data set may have identified more differences between groups. We restricted our analysis to four simple coding groups—GP, hospital, paired and pooled GP/hospital. However, it is clear that there are many further ways of categorising events, including the presence or absence of prior or subsequent coding based on the alternative half of the data set. For instance, an incident GP event with a historical hospital event may be coded differently to a GP event with no previous hospital record. However, we found that many of these theoretical categories have only a handful of cases. Furthermore, even when we examined six or seven separate smaller coding categories, similar differences in patient characteristics persisted between groups (data not shown). Our choice of four main groups was therefore a pragmatic one, which reflects the choice that would face a researcher dealing with a similar linked data set. The decision to use a 30-day limit for pairing data could also be questioned; we are unable to prove that these two events are truly the same clinical episode. The choice was again, therefore, partly pragmatic, although supported by examination of the distribution of time gaps between the GP and hospital data. We did not limit the lead-in time period prior to 1 January 2005 in any way. Length of GP records is generally greater and more variable than SMR records, and there is the potential to see a lower number of new incident events among persons with longer GP records. Our study used routine GP data, and it is possible that such profound differences may not be found with research-standard databases, such as General Practice Research Database (GPRD).21 Nonetheless, work linking primary care research databases to hospital (and other) records is ongoing, and the issues raised by our study must be acknowledged. The SMR data set only records hospital events in Scotland and thus fails to capture events in elsewhere in the UK or abroad. Similar issues face the English equivalent Hospital Episode Statistics, and a UK-wide hospital events data set would be valuable. SMR (and Hospital Episode Statistics) also provide multiple diagnostic codes for a single event. We elected to use all six diagnostic positions to ensure maximum capture of relevant hospital events. However, the robustness of low-priority diagnoses might be questioned. Nonetheless, we found similar results when we used only two diagnostic positions (data not shown). We also did not examine miscoding of events—for example, a code of angina being used rather than the code for MI. Coding of SMR is considered 99% complete and 88% accurate8; corresponding metrics are not available for PTI data (although the completeness and accuracy of Read coding of morbidity in Scottish general practice has been shown previously to be greater than 91%22). Furthermore, the two data sets use different coding systems, so completely reliable comparison is not possible. However, we used relatively broad definitions, and the Read code system is based on ICD. Nonetheless, we may in particular have missed some administrative Read codes, which might have enabled identification of additional cases in the GP group. Of course, ideally further validation of the coding should be conducted; linkage to laboratory data might be one way of achieving this. Finally, our 30-day limit for prescribing was selected from a pragmatic perspective. However, it is possible that patients who were admitted for over 30 days would not have had a new prescription issued by the GP within the 30-day post-event period, resulting in an apparent underestimation of prescribing. We believe that these numbers will be relatively small, however, and unlikely to alter the overall interpretation of our findings.

Research and policy implications

These results have significant implications for linked data; the drug management, disease severity and to some degree the patient characteristics vary depending on how the disease cohort is defined. They also have implications for the use of unlinked routine data—use of isolated primary or secondary care data may result in a biased selection of patients. This may affect patient recruitment as well as the validity and reliability of such information sources as secondary data in clinical trials, including clinical outcomes. It is similarly relevant to the public health environment. Using linked data allows one to have a more robust definition, by using pairs of GP and hospital codes only, but it is clear that the apparent incidence of a disease will be considerably lower. Alternatively, linked data enable a looser but more inclusive disease definition, using both GP and hospital data, but not relying on the coding occurring simultaneously. When using separate data from only one source, one needs to take into account that patient characteristics may not be representative of the wider population. It is difficult to recommend one coding approach over another, however, and the decision will need to be based on the specific question being posed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, patient characteristics vary depending on whether GP, hospital or combined definitions of cardiovascular events are used. In particular, disease severity as measured by mortality varies considerably. This has important implications for studies using linked routine primary and secondary care data, and for studies where information is only available from one of these sources. These issues should be acknowledged by studies using routine data as a secondary data source, and further work is merited to examine whether similar discrepancies exist for other clinical conditions or within primary care research databases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Payne RA, Abel GA, Simpson CR. A retrospective cohort study assessing patient characteristics and the incidence of cardiovascular disease using linked routine primary and secondary care data. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000723. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000723

Contributors: RAP conceived the study. RAP and GAA contributed to the study design, analysis and interpretation and to the drafting of the article. CRS acquired the data and set up the linked database. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the paper and approval of the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Scarborough P, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, et al. Coronary Heart Disease Statistics. 2010 edn London: British Heart Foundation, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erkinjuntti T, Ostbye T, Steenhuis R, et al. The effect of different diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of dementia. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1667–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rollason W, Khunti K, de Lusignan S. Variation in the recording of diabetes diagnostic data in primary care computer systems: implications for the quality of care. Inform Prim Care 2009;17:113–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle CA, Dobson AJ. The accuracy of hospital records and death certificates for acute myocardial infarction. Aust N Z J Med 1995;25:316–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng P, Gilchrist A, Robinson KM, et al. The risk and consequences of clinical miscoding due to inadequate medical documentation: a case study of the impact on health services funding. HIM J 2009;38:35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan K, Porcheret M, Croft P. Quality of morbidity coding in general practice computerized medical records: a systematic review. Fam Pract 2004;21:396–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e128–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS Hospital Data Quality—towards Better Data from Scottish hospitals. An assessment of SMR01 and Associated Data 2004–2006. Edinburgh: ISD Scotland, NHS National Services Scotland, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2009 Technical Report. Office of the Chief Statistician. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987;40:373–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan NF, Perera R, Harper S, et al. Adaptation and validation of the Charlson Index for Read/OXMIS coded databases. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy NF, Simpson CR, MacIntyre K, et al. Prevalence, incidence, primary care burden and medical treatment of angina in Scotland: age, sex and socioeconomic disparities: a population-based study. Heart 2006;92:1047–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher M, Yudkin P, Turner R, et al. An assessment of morbidity registers for coronary heart disease in primary care. ASSIST (ASSessment of Implementation STrategy) trial collaborative group. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:706–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGovern MP, Boroujerdi MA, Taylor MW, et al. The effect of the UK incentive-based contract on the management of patients with coronary heart disease in primary care. Fam Pract 2008;25:33–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donnan PT, Dougall HT, Sullivan FM. Optimal strategies for identifying patients with myocardial infarction in general practice. Fam Pract 2003;20:706–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckley BS, Simpson CR, McLernon DJ, et al. Considerable differences exist between prevalent and incident myocardial infarction cohorts derived from the same population. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1351–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbs RG, Newson R, Lawrenson R, et al. Diagnosis and initial management of stroke and transient ischemic attack across UK health regions from 1992 to 1996: experience of a national primary care database. Stroke 2001;32:1085–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagadesham VP, Aparajita R, Gough MJ. Can the UK guidelines for stroke be effective? Attitudes to the symptoms of a transient ischaemic attack among the general public and doctors. Clin Med 2008;8:366–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J 2002;144:290–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parikh NI, Gona P, Larson MG, et al. Long-term trends in myocardial infarction incidence and case fatality in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart study. Circulation 2009;119:1203–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The General Practice Research Database. http://www.gprd.com/academia/primarycare.asp (accessed 29 Jun 2011).

- 22.Murphy NF, Simpson CR, McAlister FA, et al. National survey of the prevalence, incidence, primary care burden, and treatment of heart failure in Scotland. Heart 2004;90:1129–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.