Abstract

Non-naturally occurring 20R epimer of 20-hydroxyvitamin D3 is synthesized based on chemical design and hypothesis. The 20R isomer is separated from semi-preparative HPLC and its structure is characterized. The comparison of 20R isomer to its 20S counterpart in biological evaluation demonstrates they have different behaviours in both antiproliferative and metabolic studies.

Keywords: 20R-hydroxyvitamin D3, 20S-hydroxyvitamin D3, chemical synthesis, NMR, antiproliferative activity, metabolism, CYP11A1, CYP27B1

Introduction

Vitamin D hormone carries out essential biological functions required for human health. Besides its critical role in regulating bone formation and calcium homeostasis, vitamin D hormone also regulates cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and immune responses through the activation of the nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR).1,2 Vitamin D3 is derived from a cholesterol precursor in the skin, 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC). After absorption of ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation (315 nm to 280 nm in wavelength), 7-DHC is converted to previtamin D3, which undergoes further thermally induced transformation to vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). Vitamin D3 from the diet or produced in the epidermis is biologically inactive and requires enzymatic conversion to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3, calcitriol), the active form of vitamin D3. This activation involves sequential 25- and 1α– hydroxylation in the liver and kidney, respectively.3 Unfortunately, the toxicity (hypercalcemia) induced by high levels of vitamin D largely prevents the clinical use of pharmacological doses of 1,25(OH)2D3. More than 40 metabolites of vitamin D have been reported4 and understanding the activity of these metabolites can assist in the development of new vitamin D3 analogues with beneficial actions. Searching for vitamin D analogs that retain biological efficacy and display minimal or no hypercalcemia has been pursued for several decades. As a result, several vitamin D analogs that exhibit reduced hypercalcemia are entering clinical trials and are showing great promise as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer and other diseases.5

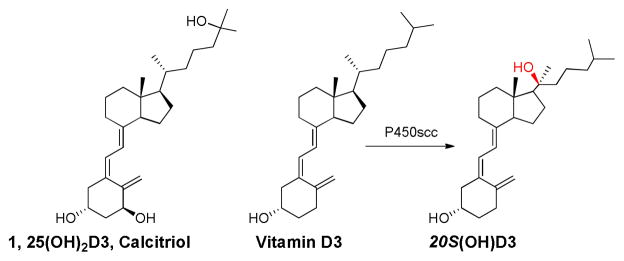

20S-hydroxyvitamin D3 (20S(OH)D3, Figure 1) is a newly isolated metabolite of vitamin D3 produced by the action of the enzyme cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1).6,7 It inhibits cell proliferation and differentiation without inducing hypercalcemia at a dose of 30 μg/kg on mice (unpublished results), stimulates VDR gene expression and also inhibits NFκβ activity with similar potency to 1,25(OH)2D3.8 We have chemically synthesized 20S(OH)D3,6b which exhibited similar biological properties to those of 20S(OH)D3 generated enzymatically using P450scc. The S configuration of C-20 in chemically synthesized 20S(OH)D3 was determined by both NMR and HPLC characterizations, and was found to be identical to the enzymatically generated metabolite. Many reported potent D3 analogs have 21β–Me configuration which corresponds to 20R(OH)D3 configuration. 9 These analogs are very potent VDR-activators with very low hypercalcemic side effect. 10 It will be very interesting to see if 20R(OH)D3 have different activity compared with 20S(OH)D3. Hansen et al. have reported the preparation of 20R(OH)D3 analogs with 22-alkynyl side chains from secosteroids. 11 In this report, we designed an efficient synthetic route to prepare 20R(OH)-7DHC from pregenolone, which following UVB irradiation and HPLC purification yielded the 20R(OH)D3 epimer. Analysis of its NMR spectra and comparison to that of 20S(OH)D3 confirmed the formation of the 20R-epimer without detectable amounts of the other.

Figure 1.

Structures of Calcitriol, Vitamin D3, and new VD3 metabolite 20S(OH)D3.

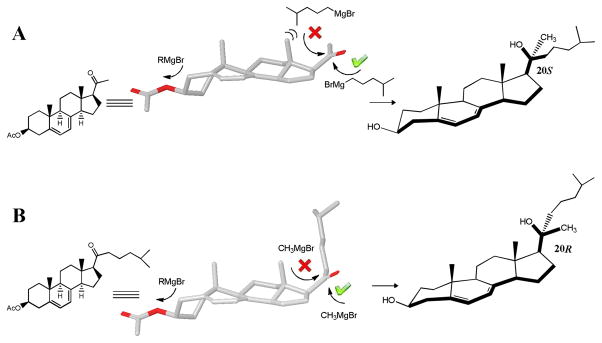

A noticeable phenomenon was reported in the preparation of 20S(OH)-7DHC that only 20S epimer was produced from the Grignard reaction, while theoretically both 20R and 20S-(OH)-7DHC should be obtained. This result suggested that the attack of Grignard agent is highly stereo-selective at the 20-cabonyl position (Figure 2). A similar phenomenon was also reported in the synthesis of 20S-hydroxycholesterol and other 20-hydroxysteroids.12 Both theoretical calculation and NMR spectra characterization6b of synthesized 20S(OH)-7DHC clearly indicate that there is a preference for the orientation of the 17-acetyl group. It is conceivable that this conformational preference dictated the outcome of the bulky side chain addition to form 20S epimer. As shown in Figure 2A, the attack of the nucleophilic Grignard reagent takes place predominantly from the less hindered “bottom” side of the carbonyl group to form 20S(OH)-7DHC, while the attack from the “top” side to form 20R(OH)-7DHC is sterically prohibited.

Figure 2.

Hypothesis to obtain 20R-epimer. Molecular models were constructed using the MM2 energy minimization algorithm in ChemBioOffice 2010 Chem 3D Pro (Version 12.0). (A). It was proved that “bottom” side attack by the bulky Grignard reagent to form 20S epimer is favoured, while attack from the “top” is prohibited due to the steric hindrance from both 18-CH3 and the steroid scaffold. (B). We hypothesize that “bottom” side attack of the small sized CH3MgI is favored by the pre-exist bulky side chain, while it is not inclined to attack from “top” side to form the 20R epimer.

The above observations encourage us to design a synthesis approach to exclusively produce 20R(OH)-7DHC. We predict that if the bulky side chain at the 20-cabonyl position is introduced in earlier synthesis steps, followed by introducing the 21-methyl group with smaller Grignard reagent CH3MgI, the 20R conformation should be obtained as the only epimer product (Figure 2B). To validate our hypothesis, we employed chemical synthesis to access material for biological evaluation. The synthesis route of 20R(OH)D3 is shown in Scheme 1.

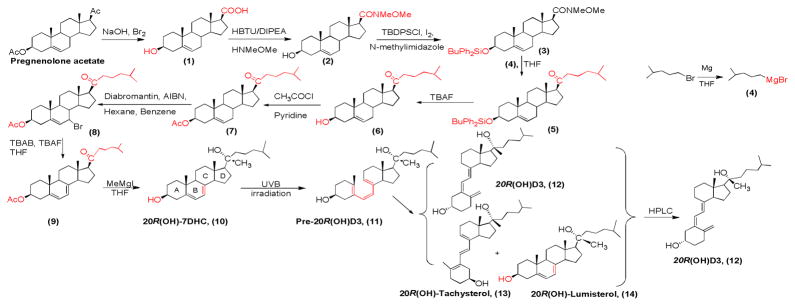

Scheme 1.

Chemical Synthesis of 20R(OH)D3

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

The synthesis of 20R(OH)-7DHC started with high yield (> 95%) conversion of pregnenolone acetate to 3β-acetoxy-etientic acid 1 under oxidation with in situ prepared NaOBr from bromine and sodium hydroxide solution.13 We tried the coupling conditions employing EDCI/HOBt/NMM to introduce Weinreb amide, but the major product separated was the intermediate active ester of benzotriazolyl carboxylate, which is close to desired compound 2 on the TLC plate but showed UV absorption. We therefore changed coupling conditions to HBTU/DIPEA, HNMeOMe·HCl salt which was reacted with 17α carboxylic acid to yield Weinreb amide in 75.9 % yield. We chose introducing silicon ether protection of the 3β-hydroxyl in the next step to reduce the consumption of (4-methylpentyl)magnesium bromide 4, which was prepared from 1-bromo-4-methylpentane and magnesium turnings in anhydrous THF. Three silyl chlorides (TMSCl, TBDMSCl, and TBDPSCl) were used in the presence of various bases such as triethylamine, imidazole, and N-methylimidazole. After comparing and examination of the above conditions, we chose TBDP-SCl as the silylation agent for introducing chromophore to compound 3 and using N-methylimidazole as the base with iodine as the catalyst to accelerate the reaction (89.1% yield).14 Grignard reaction of compound 3 and (4-methylpentyl) magnesium bromide yielded the bulky side chain ketone 5 with 47.6% yield.

We designed the synthesis route by introducing a 5, 7-diene to compound 5 under 1,3-dibromo-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (dibromantin)/AIBN/TBAB/TBAF condition, thus the deprotection of silicon ether can be used in the same step under TBAF treatment. However, we found from TLC analysis that there was a more complex set of reaction products with siliyl protected substrate compared with a similar reaction from acetyl protected substrate in preparation of 20S(OH)-7DHC. Neither the diabromantin condition nor the NBS/γ-collidine reaction afforded satisfactorily pure 5,7-diene product. Moreover, 5, 7-diene structures are known to be unstable under light and acidic conditions. Thus we chose to postpone the formation of the 5, 7-diene and replace TBDPS protection with acetyl protection. The deprotection of silicon ether with TBAF afforded the 3β-hydroxyl compound 6 in satisfactory yield (quantitative). Introducing the acetyl protecting group at 3β-OH with acetyl chloride and pyridine gave compound 7 in an 88.7% yield.

Transformation of 7 into the 5, 7-diene 9 was carried out by diabromantin/AIBN employed in the synthesis of 20S(OH)-7DHC using hexane and benzene as the solvent in the bromination step. Treatment of TBAB/TBAF in THF yielded the diene via dehydrobromination. The purification of the product 9 (34 % overall yield) was carried out through silver nitrate impregnated silica gel chromatography to remove other impurities such as 4, 6-diene by-products. Grignard reaction of 5, 7-diene substrate 9 with CH3MgI afforded the precursor 20R(OH)-7DHC 10 (yield 85.6 %).

For B-ring opening, 20R(OH)-7DHC 10 was subjected to UVB irradiation for 20 min in a quartz tube at 65°C to achieve the maximum conversion to pre-20R(OH)D3 (11). The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for one week, which produced a mixture of 20R(OH)D3 (12), 20R(OH)-tachysterol (13), 20R(OH)-lumisterol (14), and other minor 20R(OH)-products. The photolysis reaction and subsequent time-dependent conversion to 20R(OH)D3 was analyzed by HPLC. The final 20R(OH)D3 was purified by a Gilson Semi-preparative HPLC system.

Different epimers of both 20(OH)-7DHC precursors and final 20-hydroxyvitamin D3 analogs have characteristic HPLC retention times (RT). The RT of precursor 20R(OH)-7DHC appeared at 16.0 min and its 20S counterpart could be eluted earlier at 13.8 min under the same HPLC conditions. The final 20R(OH)D3 showed a slight difference as compared to the 20S(OH)D3 isomer peak at RT of 12.3 min vs. 12.2 min, respectively. (see Supplemental files p6-9).

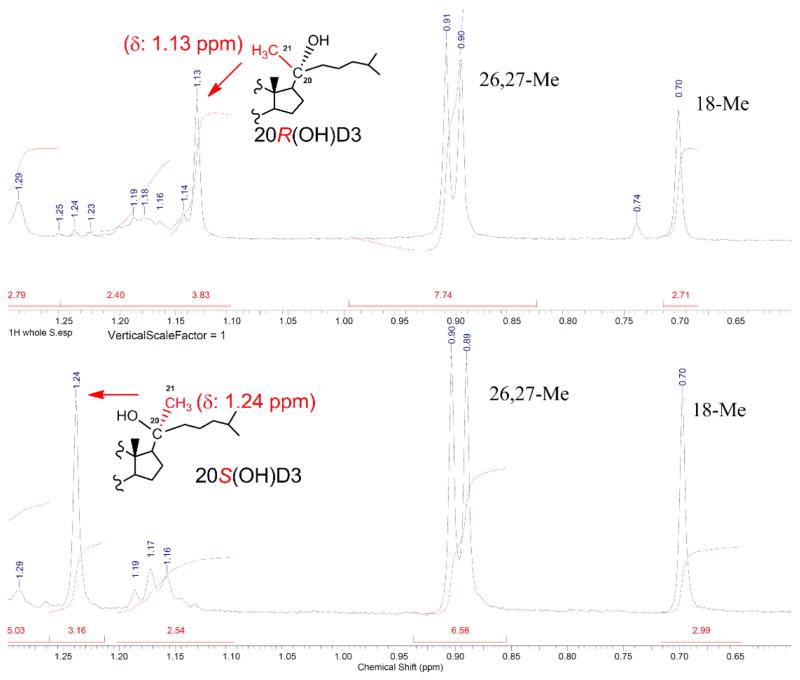

1H NMR comparisons of both 20(OH)-7DHC epimer precursors and final 20(OH)D3 products are effective methods to identify 20R and 20S isomers of vitamin D3 analogs. It is established that in the pregnane compounds, the 1H NMR chemical shifts for the 21-Me in the 20S-OH isomers are downfield relative to 20R-OH isomers.12a They have distinct values and are the basis used to assign the absolute configuration at C20 of these two epimers. The R-configuration at C20 can be deduced from comparisons of 1H NMR spectra of 21-methyls in both precursor 20R/S(OH)-7DHC and final 20R/S(OH)D3. An upfield chemical shift (1.16 ppm) was obtained for the 21-methyl in 20R(OH)-7DHC, while in 20S(OH)-7DHC a downfield chemical shift at 1.27 ppm was observed. Similarly, we found that the 21-Me showed a chemical shift at 1.13ppm in 20R-isomer of 20(OH)D3, while a downfield chemical shift of 1.24 ppm was observed for 21-Me in 20S(OH)D3 (As show in Figure 3, 1H NMR figures of 20R/S(OH)-7DHC are shown in supplemental files p1-3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of 1H NMR Chemical shifts for 21-Me in 20R and 20S(OH)D3. 21-Methyl showed a chemical shift at 1.13 ppm in 20R(OH)D3, while the downfield chemical shift 1.24 ppm was observed for 21-Me in 20S(OH)D3.

Biological Evaluations

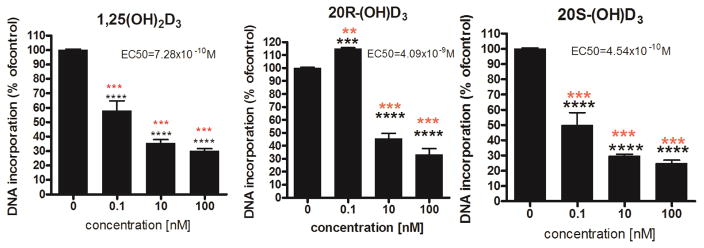

Previously we documented that 20S(OH)D3 and related 20S(OH)D2 inhibit proliferation and stimulate differentiation of human epidermal keratinocytes (HEKn) in a dose dependent manner similar to that of 1,25(OH)2D3 with the highest potency at concentrations >10−10M. 6b, 8b, 15 In the present studies we compared the antiproliferative activity of 20S(OH)D3 with its epimer, 20R(OH)D3. Figure 4 shows that 20S(OH)D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 (positive control) exhibited similar dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation, as expected, with an EC50 of 7.28×10−10 M and 4.54×10−10 M, respectively. In contrast, 20R(OH)D3 had a biphasic effect, slightly stimulating DNA synthesis at a concentration of 0.1 nM, with significant (p<0.001) inhibition of cell proliferation at concentrations ≥10 nM. This inhibitory effect was similar to that of 20S(OH)D3 (<50% of control), however, with higher EC50=4.09×10−9M. These data show a clear difference between the R and S isomers at low concentrations of the ligand (0.1 nM) and similar effects at the higher concentrations, however, with lower potency for the R form. In separate experiment we demonstrated that 20S(OH)D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibit colony formation by HaCaT epidermal keratinocytes with similar potency, while 25(OH)D3 has no- or a small effect (SI S30).

Figure 4.

20(OH)D3 isomers inhibit growth of human keratinocytes. HEKn cells were treated for 24 h with 1,25(OH)2D3, or R, or S epimers of 20(OH)D3 at the concentrations listed. The rate of 3H-thymidine incorporation into DNA served as a measure of proliferative activity. Data are presented as mean ±SD, n=4. Incorporation into DNA is shown as a percentile (%) of control (ethanol treated cells). Statistical significance was measured using Student t-test (*) and one-way ANOVA (*) presented as **p<0.05, ***p<0.01, and ****p<0.001.

Metabolism of 20(OH)D3 by CYP11A1 and CYP27B1

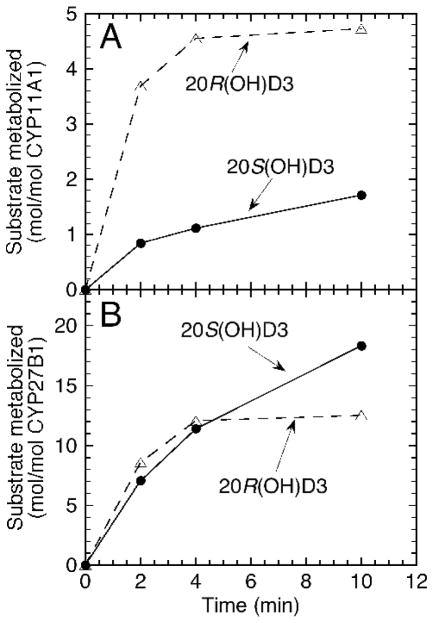

Since biologically generated 20S(OH)D3 is derived from the action of P450scc on vitamin D3 and can be further metabolized to dihydroxy- (e.g. 17,20(OH)2D3; 20,22(OH)2D3; 20,23(OH)2D3) and trihydroxy- (e.g. 17,20,23(OH)3; 20,22,X(OH)3D3) metabolites by this enzyme,6a, 7, 16 we compared the ability of P450scc to metabolize 20S(OH)D3 and 20R(OH)D3 (Figure 5A). Due to the formation of many products, metabolites were characterized in the case of the 20Sisomer 16 but not for the 20R-isomer, data are presented as the amount of substrate metabolized. 20R(OH)D3 proved to be a much better substrate than 20S(OH)D3 for P450scc with 58% being consumed in the first 2 min of incubation for the R-isomer, but only 13% for the S-isomer. While the structures of the products from 20R(OH)D3 remain to be elucidated, HPLC retention times are consistent with formation of di- and tri-hydroxy derivatives analogous to those produced from the 20S-isomer. 16

Figure 5.

Metabolism of 20(OH)D3 isomers by CYP11A1 and CYP27B1. Substrates were incorporated into phospholipid vesicle and incubated with CY11A1 (A) or CYP27B1 (B) then substrate and products extracted with dichloromethane and analyzed by reverse phase HPLC

CYP27B1 catalyzes the 1α-hydroxylation of a range of vitamin D derivatives including 20(OH)D3 and 20(OH)D2.15, 17 In the case of 20S(OH)D3, the 1α,20S-dihydroxyvitamin D3 product exhibits calcemic activity which is in contrast to the parent 20S(OH)D3 which lacks this activity.8a We therefore compared the ability of CYP27B1 to metabolize 20S(OH)D3 and 20R(OH)D3 (Figure 5B). Each isomer was metabolized to a single product at comparable initial rates but subsequently the rate declined more rapidly for the R-isomer than the S-isomer. This phenomenon could suggest that the 20R(OH)D3 isomer could show less calcemic toxicity than 20S(OH)D3 due to its lower efficiency of 1α-hydroxylation. The hypercalcemic effects of the 1α-hydroxy-metabolites will be examined in future studies.

Conclusion

We chemically synthesized the R epimer of 20(OH)D3 based on the preferred conformation of the reactant and the associated strong steric preference for the formation of this isomer. NMR characterization of the chemically synthesized compound and comparisons with 20S(OH)-7DHC and 20S(OH)D3 confirmed the R chirality at the C20 position. Biological studies demonstrated the antiproliferative activity of R-epimer on keratinocytes, similar to that of the S-epimer and 1,25(OH)2D3 at concentrations of 10 nM and 100 nM, with a noted difference (opposite effect) at lower concentrations. This overlapping but different behavior was further demonstrated by the ability of P450scc and CYP27B1 to metabolize both the R and S-epimers but with the different efficiencies. 20R(OH)D3 was a better substrate for P450scc than 20S(OH)D3, while 20S(OH)D3 was a better substrate for CYP27B1 than for 20R(OH)D3. The latter could explain the higher potency of 20S(OH)D3 in the inhibition of HEKn cell proliferation. Alternatively, P450scc which is present in keratinocytes18, may cause a more rapid inactivation of the R-epimer than the Sepimer, however it remains to be established if the products of P450scc action on 20R(OH)D3 are more or less potent than the parent compound. In-depth investigations of the biological activity of 20R/S(OH)D3 epimers for anti-inflammatory and hypercalcemic effects, the nature of signal transduction pathways induced by these compounds and the potential role of 1-hydroxylation in these processes will be carried out in the future.

Experimental Procedures

All reagents for the synthesis were purchased from commercial sources and were used without further purification. Moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out under an argon atmosphere. NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker ARX-300 MHz (Billerica, MA) or an Agilent Inova-500 MHz spectrometer (Santa Clara, CA). Mass spectral data was collected on a Bruker ESQUIRE-LC/MS system equipped with an ESI source. High resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Waters Xevo G2 QTOF LCMS using ESI. The purity of the final compounds was analyzed by an Agilent 1100 HPLC system (Santa Clara, CA). Purities of the compounds were established by careful integration of areas for all peaks detected and ≥ 95%.

(1S,Z)-3-((E)-2-((7αS)-1-((R)-2-hydroxy-6-methylheptan-2-yl)-7α-methylhexahydro-1H-inden-4(2H)-ylidene)ethylidene)-4-methylenecyclohexanol (20R(OH)D3, 12)

A methanol solution of 20R(OH)-7DHC (10) (5 mg, 2 mg/mL) was subjected to UVB irradiation for 20 min in a quartz tube at 65°C, using a Rayonet RPR-100 photochemical reactor (Branford, CT). The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for one week to allow the conversion from pre-20R(OH)D3 (11) to 20R(OH)D3 (12). The reaction mixture was analyzed using an Agilent 1100 HPLC system (Santa Clara, CA) to confirm the production of 20R(OH)D3 and to optimize the condition for the separation using a semi-preparative HPLC system. The reaction mixture (5 μL) of irradiated 20R(OH)-7DHC was injected by an autosampler onto a 5 μM Phenomenex Luna-PFP column (250 × 4.6 mm) (Torrance, CA) with mobile phase of 85% methanol–water at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The separation of reaction mixture was conducted using a Gilson semi-preparative HPLC System with a 5 μM Phenomenex Luna-PFP semi-preparative column (250 × 10 mm), and a mobile phase as 85% methanol-water at a flow rate of 6.0 mL/min. Fractions were collected based on a pre-setup UV threshold and were reanalyzed by RP-HPLC. Fractions containing above 95% of pure compound 12 (for 240 nm and 265 nm spectra) were pooled, freeze dried, and characterized by NMR and Mass Spectrometry. 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOH-d4): δ 6.22 (d, 1 H, J = 10.0 Hz), 6.02 (d, 1 H, J = 10.0 Hz), 5.04 (s, 1 H), 4.74 (s, 1 H), 3.78-3.74 (m, 1 H), 2.87-2.84 (m, 1 H), 2.54-2.52 (m, 1 H), 2.42-2.39 (m, 1 H), 2.21–2.09 (m, 2 H), 2.01-1.96 (m, 1 H), 1.74-1.14 (m, 26 H), 1.13 (s, 3 H), 0.91 (d, 6 H, J = 5.0 Hz), 0.71 (s, 3 H). MS (ESI) m/z 423.4 [M+Na]+, HPLC purity 100%, HRMS calculated for C27H45O2 [M+H]+ 401.3420. found 401.3423.

Metabolic studies of 20(OH)D3

To test enzymatic metabolism, the 20S(OH)D3 and 20R(OH)D3 substrates were incorporated into phospholipid vesicles prepared from dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine and cardiolipin as before,19 with the ratio of substrate to phospholipid being 0.025 mol/mol phospholipid. Vesicles were incubated with 2 μM bovine CYP11A1 or 0.06 μM human CYP27B1 at 37°C for up to 10 min. Products and remaining substrate were extracted with dichloromethane, and measured by reverse phase HPLC as described before.16, 17b

Inhibition of proliferation by different epimers of 20(OH)D3 in comparison to Calcitriol

Neonatal human epidermal keratinocytes (HEKn) were isolated form neonatal fore-skin of African-American donors and grown in HKM (Lonza) medium supplemented with HKGF (Lonza) as described previously. 8b, c For the cell proliferation assay the cells from a third passage were seeded into 24-well plates (TPP, Switzerland) and grown to ~80% confluence. Secosteroids were dissolved in ethanol and then diluted in keratinocyte medium containing 0.1% BSA (Sigma). Cells were incubated for 24 h then 1 μCi/ml [3H]-thymidine (Moravek Biochemicals Inc., Brea, CA) was added and cells were incubated for a further 4 h. Excess of unbound thymidine was removed by washing cells with PBS. Cells were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (Sigma) and then the precipitate dissolved with 1N NaOH. The solution was collected in vials and thymidine incorporation was determined using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman LS 6000, Santa Clara, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors thank College of Pharmacy in UTHSC; the Van Vleet Endowed Professorship, UT Research Foundation, University of Western Australia; and NIH/NIAMS R01AR052190 and 1R01AR056666-01A2 to AS for financial support. We thank Mr. Jerrod Scarborough for performing HRMS.

Abbreviations

- D3

Vitamin D3

- 7-DHC

7-dehydrocholesterol

- 1,25(OH)2D3

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- P450scc

CYP11A1

- HBTU

O-Benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate

- TMSCl

Trimethylsilyl chloride

- DIPEA

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine

- TBDMSCl

tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride

- AIBN

2-2′-azobisisobutyronitrile

- TBAF

tetrabutylammonium fluoride

- TBDPSCl

tert-butylchlorodiphenylsilane

- RT

Room temperature

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Preparations and spectra of intermediates are available via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Plum LA, DeLuca HF. Vitamin D, disease and therapeutic opportunities. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2010;9(12):941–955. doi: 10.1038/nrd3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lappe JM. The Role of Vitamin D in Human Health: A Paradigm Shift. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 2011;16:58–72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1689S–16896S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holick MF. Vitamin D Deficiency. The New England Journal of Medcine. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouillon R, Okamura WH, Norman AW. Structurefunction relationships in the vitamin D endocrine system. Endocrine reviews. 1995;16(2):200–257. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-2-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Pinette KV, Yee YK, Amegadzie BY, Nagpal S. Vitamin D receptor as a drug discovery target. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry. 2003;3(3):193–204. doi: 10.2174/1389557033488204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Takahashi T, Morikawa K. Vitamin D receptor agonists: opportunities and challenges in drug discovery. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2006;6(12):1303–1316. doi: 10.2174/156802606777864917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schwartz GG. Vitamin D and intervention trials in prostate cancer: from theory to therapy. Annals of epidemiology. 2009;19(2):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Slominski A, Semak I, Zjawiony J, Wortsman J, Li W, Szczesniewski A, Tuckey RC. The cytochrome P450scc system opens an alternate pathway of vitamin D3 metabolism. The FEBS journal. 2005;272(16):4080–4090. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li W, Chen J, Janjetovic Z, Kim TK, Sweatman T, Lu Y, Zjawiony J, Tuckey RC, Miller D, Slominski A. Chemical synthesis of 20S-hydroxyvitamin D3, which shows antiproliferative activity. Steroids. 2010;75(12):926–935. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Guryev O, Carvalho RA, Usanov S, Gilep A, Estabrook RW. A pathway for the metabolism of vitamin D3: unique hydroxylated metabolites formed during catalysis with cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(25):14754–14759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336107100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tuckey RC, Li W, Zjawiony JK, Zmijewski MA, Nguyen MN, Sweatman T, Miller D, Slominski A. Pathways and products for the metabolism of vitamin D3 by cytochrome P450scc. The FEBS journal. 2008;275(10):2585–2596. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Slominski AT, Janjetovic Z, Fuller BE, Zmijewski MA, Tuckey RC, Nguyen MN, Sweatman T, Li W, Zjawiony J, Miller D, Chen TC, Lozanski G, Holick MF. Products of vitamin D3 or 7-dehydrocholesterol metabolism by cytochrome P450scc show antileukemia effects, having low or absent calcemic activity. PloS one. 2010;5(3):e9907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zbytek B, Janjetovic Z, Tuckey RC, Zmijewski MA, Sweatman TW, Jones E, Nguyen MN, Slominski AT. 20-Hydroxyvitamin D3, a product of vitamin D3 hydroxylation by cytochrome P450scc, stimulates keratinocyte differentiation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2008;128(9):2271–2780. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Janjetovic Z, Zmijewski MA, Tuckey RC, DeLeon DA, Nguyen MN, Pfeffer LM, Slominski AT. 20-Hydroxycholecalciferol, product of vitamin D3 hydroxylation by P450scc, decreases NF-kappaB activity by increasing IkappaB alpha levels in human keratinocytes. PloS one. 2009;4(6):e5988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tocchini-Valentini G, Rochel N, Wurtz JM, Mitschler A, Moras D. Crystal structures of the vitamin D receptor complexed to superagonist 20-epi ligands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(10):5491–5496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091018698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Liu YY, Collins ED, Norman AW, Peleg S. Differential interaction of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analogues and their 20-epi homologues with the vitamin D receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272(6):3336–3345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang W, Freedman LP. 20-Epi analogues of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 are highly potent inducers of DRIP coactivator complex binding to the vitamin D3 receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274(24):16838–16845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen KB, Claus Aage S. Vitamin D analogues containing a hydroxy group in the 20-position. 5589471. United States Patent, US. 1996

- 12.(a) Mijares A, Cargill DI, Glasel JA, Lieberman S. Studies on the C-20 epimers of 20-hydroxycholesterol. The Journal of organic chemistry. 1967;32(3):810–812. doi: 10.1021/jo01278a066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nes WR, Varkey TE. Conformational analysis of the 17(20) bond of 20-keto steroids. The Journal of organic chemistry. 1976;41(9):1652–1653. doi: 10.1021/jo00871a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Komori MHT. Structures of thornasterols A and B (biologically active glycosides from asteroidia, XI) Tetrahedron Letters. 1986;27(29):3369–3372. [Google Scholar]

- 13.JJCS Optical Rotatory Dispersion Studies. XLI. a-Haloketones (Part 9). Bromination of Optically Active cis-1-Decalone. Demonstration of Conformational Mobility by Rotatory Dispersion. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:736–743. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartoszewicz AK, Marcin, Stawinski Jacek. Iodine-promoted silylation of alcohols with silyl chlorides. Synthetic and mechanistic studies. Tetrahedron. 2008;64(37):8843–8850. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slominski AT, Kim TK, Janjetovic Z, Tuckey RC, Bieniek R, Yue J, Li W, Chen J, Nguyen MN, Tang EK, Miller D, Chen TC, Holick M. 20-Hydroxyvitamin D2 is a noncalcemic analog of vitamin D with potent antiproliferative and prodifferentiation activities in normal and malignant cells. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2011;300(3):C526–541. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00203.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuckey RC, Li W, Shehabi HZ, Janjetovic Z, Nguyen MN, Kim TK, Chen J, Howell DE, Benson HA, Sweatman T, Baldisseri DM, Slominski A. Production of 22-hydroxy metabolites of vitamin d3 by cytochrome p450scc (CYP11A1) and analysis of their biological activities on skin cells. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2011;39(9):1577–1588. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Tang EK, Li W, Janjetovic Z, Nguyen MN, Wang Z, Slominski A, Tuckey RC. Purified mouse CYP27B1 can hydroxylate 20,23-dihydroxyvitamin D3, producing 1alpha,20,23-trihydroxyvitamin D3, which has altered biological activity. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2010;38(9):1553–1559. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.034389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang EK, Voo KJ, Nguyen MN, Tuckey RC. Metabolism of substrates incorporated into phospholipid vesicles by mouse 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1alphahydroxylase (CYP27B1) The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2010;119(3–5):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slominski A, Zjawiony J, Wortsman J, Semak I, Stewart J, Pisarchik A, Sweatman T, Marcos J, Dunbar C, RCT A novel pathway for sequential transformation of 7-dehydrocholesterol and expression of the P450scc system in mammalian skin. European journal of biochemistry/FEBS. 2004;271(21):4178–4188. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuckey RC, Nguyen MN, Slominski A. Kinetics of vitamin D3 metabolism by cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) in phospholipid vesicles and cyclodextrin. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2008;40(11):2619–2626. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.