Background: Photosystem II, the water-splitting enzyme, includes a protein, D1, which can be coded by three different psbA genes in Thermosynechococcus elongatus.

Results: In PsbA2-PSII, the environment of TyrZ is different from that in PsbA1-PSII and PsbA3-PSII.

Conclusion: The geometry of the TyrZ-O···H···Nϵ-His-190 bonding is an important parameter for PSII activity.

Significance: The environment of the cofactors is involved in the tuning of the electron transfer efficiency.

Keywords: Bioenergetics, Bioenergetics/Electron Transfer Complex, Cyanobacteria, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR), Electron Transfer, Photosynthesis, Photosystem II, PsbA Protein, Hydrogen Bond, Tyrosine Radical

Abstract

The main cofactors that determine the photosystem II (PSII) oxygen evolution activity are borne by the D1 and D2 subunits. In the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus, there are three psbA genes coding for D1. Among the 344 residues constituting D1, there are 21 substitutions between PsbA1 and PsbA3, 31 between PsbA1 and PsbA2, and 27 between PsbA2 and PsbA3. Here, we present the first study of PsbA2-PSII. Using EPR and UV-visible time-resolved absorption spectroscopy, we show that: (i) the time-resolved EPR spectrum of TyrZ• in the (S3TyrZ•)′ is slightly modified; (ii) the split EPR signal arising from TyrZ• in the (S2TyrZ•)′ state induced by near-infrared illumination at 4.2 K of the S3TyrZ state is significantly modified; and (iii) the slow phases of P680+⋅ reduction by TyrZ are slowed down from the hundreds of μs time range to the ms time range, whereas both the S1TyrZ• → S2TyrZ and the S3TyrZ• → S0TyrZ + O2 transition kinetics remained similar to those in PsbA(1/3)-PSII. These results show that the geometry of the TyrZ phenol and its environment, likely the Tyr-O···H···Nϵ-His bonding, are modified in PsbA2-PSII when compared with PsbA(1/3)-PSII. They also point to the dynamics of the proton-coupled electron transfer processes associated with the oxidation of TyrZ being affected. From sequence comparison, we propose that the C144P and P173M substitutions in PsbA2-PSII versus PsbA(1/3)-PSII, respectively located upstream of the α-helix bearing TyrZ and between the two α-helices bearing TyrZ and its hydrogen-bonded partner, His-190, are responsible for these changes.

Introduction

Light-driven water oxidation catalyzed by photosystem II (PSII)3 is the first step in the photosynthetic production of biomass, fossil fuels, and O2 on earth. Refined three-dimensional x-ray structures from 3.5 to 2.9 Å resolution have been obtained using PSII isolated from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus (1, 2). More recently, an x-ray structure at 1.9 Å resolution has been obtained using PSII isolated from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus vulcanus (3). PSII core complex is made up of 17 transmembrane protein subunits and 3 extrinsic proteins. In total, it contains 35 chlorophylls, 2 pheophytins, 2 hemes, 1 non heme iron, 2 quinones, 3–4 calcium ions, one of which is part of the Mn4CaO5 cluster, 3 chloride ions, two of which are at 7 Å from the Mn4CaO5 cluster, 11–12 carotenoid molecules, more than 20 lipids, and over 1300 water molecules (3).

The main cofactors involved in the function of PSII are integral components of the D1 and D2 proteins. The exciton resulting from the absorption of a photon is transferred to the photochemical trap, which undergoes a charge separation. The positive charge is then stabilized on P680, a weakly coupled chlorophyll dimer (PD1 and PD2). Then, P680+⋅ oxidizes a tyrosine residue of the D1 polypeptide, TyrZ, which in turn oxidizes the Mn4CaO5 cluster. On the acceptor side, the pheophytin anion (PheoD1˙̄) transfers the electron to the primary quinone electron acceptor, QA, which in turn reduces the second quinone, QB. QA is tightly bound and acts as a one-electron carrier, whereas QB acts as a two-electron and two-proton acceptor with a stable semiquinone intermediate, QB˙̄. Although the QB˙̄ semiquinone state is tightly bound, the quinone and quinol forms are exchangeable with the quinone pool in the thylakoid membrane (e.g. Refs. 4–9).

The Mn4CaO5 cluster acts both as a device accumulating oxidizing equivalents and as the catalytic site for water oxidation. The enzyme cycles sequentially through five redox states, denoted Sn, where n stands for the number of oxidizing equivalents stored. Upon formation of the S4 state, two molecules of water are rapidly oxidized, the S0 state is regenerated, and O2 is released (10, 11).

Cyanobacterial species have multiple psbA variants coding for the D1 protein (e.g. Refs. 12–20). These different genes are known to be differentially expressed depending on the environmental conditions (e.g. Refs. 12–18). In particular, specific up/down-regulations of one of these genes under high light conditions is indicative of a photo-protection mechanism. For example, the mesophilic cyanobacterium, Synechocystis PCC 6803, has three psbA genes. Two of these (psbAII and psbAIII) produce an identical D1. Nevertheless, although psbAII is expressed under the “normal” cultivation conditions, transcription of psbAIII is induced by high light or UV light (15), and that of psbAI seems triggered by microaerobic conditions (18). T. elongatus also has three different psbA genes in its genome (20). The comparison of the mature D1 amino acid sequence deduced from the psbA3 gene with those of the psbA1 and psbA2 genes points to a difference of 21 and 31 residues, respectively (see supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). It has been reported that in T. elongatus, psbA1 is constitutively expressed under normal laboratory conditions, whereas the transcription of psbA3 occurred under high light or UV light conditions (16, 21, 22).

In T. elongatus, the change of Q130 in PsbA1-PSII to E130 in PsbA3-PSII has been shown to increase the midpoint potential of PheoD1/PheoD1˙̄ by 17 mV from −522 mV in PsbA1-PSII (23) to −505 mV in PsbA3-PSII (19). Because this increase was half the one observed upon single site-directed mutagenesis in Synechocystis PCC 6803 (24, 25), this led us to propose that the effects of the D1-Q130E substitution could be, at least partly, compensated for by some of the additional amino acid changes associated with the PsbA3 for PsbA1 substitution (19). For manganese-depleted PSII and above pH 7.5, where the phenolic hydroxyl group of TyrZ hydrogen-bonds H190, the proton acceptor, TyrZ oxidation by P680+⋅ is controlled by its prior deprotonation (26), and the electron transfer rate between P680+⋅ and TyrZ has been found to be slightly faster in PsbA3-PSII (global t½ ∼100 μs) than in PsbA1-PSII (global t½ ∼200 μs (19). The temperature dependences of the S2QA˙̄ charge recombination in PsbA1 and PsbA3 have shown that the environments of QA and, as a consequence, its redox potential, are likely to be different (19). The exchange of S270 in PsbA1 for A270 in PsbA3 has been suggested to influence the stabilization of the sulfoquinovosyl-diacylglycerol molecule that lies between QB and nonheme iron (27). Maybe as a consequence, the binding of bromoxynil in PsbA3-PSII and in PsbA1-PSII has been found to differ, suggesting that the QB pocket had different properties. It has been also found that the midpoint potential of the FeIII/FeII couple was likely higher in PsbA1-PSII than in PsbA3-PSII (28). In addition, under photo-inhibitory conditions, the accelerated decrease in O2 evolution in WT*1 4 (producing PsbA1-PSII) cells was found to correlate with a much faster inhibition of the S2 state formation than in WT*3 (producing PsbA3-PSII) cells (29).

Although there have been an increasing number of studies aimed at characterizing the properties of PsbA1-PSII when compared with those of PsbA3-PSII, those of PsbA2-PSII have not yet been reported. In the present work, we describe the first construction of a T. elongatus deletion mutant lacking both the psbA1 and the psbA3 genes and expressing only psbA2. We focused our first characterization of PsbA2-PSII on the electron transfer reactions involving TyrZ. Using continuous wave EPR at helium temperature, time-resolved EPR at room temperature, and time-resolved UV-visible absorption spectroscopy, it is shown that the properties of TyrZ are modified in PsbA2-PSII when compared with those in Psb(A1/3)-PSII.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of T. elongatus Mutants

The construction of the ΔpsbA1ΔpsbA2 T. elongatus deletion mutant (WT*3) from a T. elongatus 43-H strain that had a His6 tag on the C terminus of CP43 (32) has been previously described in Ref. 33.

For making the ΔpsbA1ΔpsbA3 T. elongatus deletion mutant (WT*2) (Fig. 1), first, the psbA1 gene and its promoter region (∼180 bp) were substituted together from the 43-H strain with a chloramphenicol-resistant cassette (∼1300 bp) by using the plasmid vector pBΔpsbA2. Then, the psbA3 gene was substituted with a spectinomycin/streptomycin resistance gene cassette (∼2100 bp) by using the plasmid pBΔpsbA3. For construction of pBΔpsbA1, a DNA fragment of ∼2300 bp of the psbA2 gene (tlr1844) including its promoter region (∼180 bp) and the 3′-flanking region of psbA2 (∼1000 bp) was cloned from T. elongatus wild-type genomic DNA by PCR amplification and subcloned into a plasmid vector pBluescript II SK+ at EcoRV and XhoI sites. Next, a chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette (∼1300 bp) was ligated to the upstream of the psbA2 gene at BamHI and EcoRV of the plasmid DNA. Then, a separately amplified ∼900-bp DNA fragment of the 3′-flanking region of psbA1 (but without the psbA1 promoter region) was ligated to the subcloned plasmid vector at SacI and BamHI. For the construction of pBΔpsbA3, a DNA fragment of ∼900 bp of the 3′-flanking region of the psbA3 (tlr1477) was cloned from T. elongatus wild-type genomic DNA by PCR amplification and subcloned into a plasmid vector pBluescript II SK+ between SacI and EcoRI sites. Then, a spectinomycin/streptomycin resistance gene cassette (∼2100 bp) was inserted at PstI and SacI. Then, a separately amplified ∼1100-bp DNA fragment of the 5′-flanking region of psbA3 was ligated to the subcloned plasmid vector at SphI and PstI.

FIGURE 1.

Map around psbA1 and psbA2 and around psbA3 in T. elongatus genome (A–C) and agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified products by PCR (D). A, wild-type, all three psbA genes are intact. In B, for making WT*2, psbA1 with 180 bp of the promoter region was deleted by substitution of a chloramphenicol-resistant (CmR) cassette, and psbA3 was substituted by a spectinomycin (Sp)/streptomycin-resistant (SmR) cassette. In C, for making WT*3, both psbA1 and psbA2 were substituted by a chloramphenicol-resistant cassette. Primers are shown as short arrows, and P1, P2, P3, and P4 indicate annealing position on their T. elongatus genome DNA. The double-pointed arrows show the length of the DNA amplified by PCR with using the appropriate primers. D, agarose gel (1%) electrophoresis of amplified products by PCR using P1 and P2 primers (lanes 1–3) and using P3 and P4 primers (lanes 5–7). Lanes 1 and 5 correspond to the wild type; lanes 2 and 6 correspond to the WT*2 strain; lanes 3 and 7 correspond to the WT*3 strain; and lane 4 corresponds to a 1-kb ladder marker (Toyobo).

The T. elongatus transformants were selected as single colonies on DTN agar plate containing appropriate antibiotics (25 μg ml−1 spectinomycin, 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 40 μg ml−1 kanamycin, and 5 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol). Segregation of all genome copies was confirmed by difference in length of amplified DNA by PCR using the P1 primer (5′-GCTGTACTGGCCATCGCTGGGCACCACTCG-3′) and P2 primer (5′-GGACTTATCACTACTTATCACTAGAGAGGT-3′) for psbA1–psbA2 region, and using the P3 primer (5′-GGTTGGATCCCCAGCCAGCGATCGCGGGAG-3′) and P4 primer (5′-CCATGCCCGCAAAACAGC-3′) for psbA3 region as shown in Fig. 1. Complete segregation of the deletion mutants was confirmed by PCR amplification as shown in Fig. 1D. In the wild type, a 3900-bp DNA fragment including both psbA1 and psbA2 was amplified by P1 and P2 primers (lane 1). In contrast, a 4000-bp fragment (lane 2) and a 2850-bp fragment (lane 3) were amplified with using the same combination of the primers in WT*1 and WT*3, respectively. In the region of psbA3, a 2200-bp fragment was amplified with P3 and P4 primers in both wild-type and WT*3 genomes (lanes 5 and 7), whereas a 3100-bp fragment was amplified in WT*2 genome (lane 6).

Purification of PSII

PSII were purified with the protocol already described (28). PSII samples were suspended in 1 m betaine, 10% glycerol, 15 mm CaCl2, 15 mm MgCl2, 40 mm MES, pH 6.5 adjusted with NaOH. For the low temperature X-band EPR experiments, glycerol was omitted because its presence decreases the yield of the near-infrared induced split EPR signal in the S3 state.

For manganese depletion, PSII samples were diluted ∼10-fold in a medium containing 1.2 m Tris-HCl (pH 9.2) and were incubated under room light at 4 °C for 1 h. The samples were collected by centrifugation (15 min at 170, 000 × g) after the addition of 1.2 m Tris (pH 9.2) containing 50% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000 so that the final PEG concentration was 12%. The pellet was resuspended in a medium containing 1 m betaine, 10% glycerol, 15 mm CaCl2, 15 mm MgCl2, 40 mm MES, pH 6.5 adjusted with NaOH, and 12% PEG. After a new centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 1 m betaine, 10% glycerol, 15 mm CaCl2, 15 mm MgCl2, 40 mm MES, pH 6.5 adjusted with NaOH.

Oxygen Evolution Measurements

Oxygen-evolving activity of purified PSII (5 μg of Chl ml−1) was measured under continuous saturating white light at 25 °C by polarography using a Clark type oxygen electrode (Hansatech). A total of 0.5 mm 2,6-dichloro-p-benzoquinone (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide) was added as an electron acceptor.

EPR Spectroscopy

For helium temperature measurements, continuous wave EPR spectra were recorded with a Bruker Elexsys 500 X-band spectrometer equipped with a standard ER 4102 (Bruker) X-band resonator, a Bruker teslameter, an Oxford Instruments cryostat (ESR 900), and an Oxford ITC504 temperature controller. Flash illumination at room temperature was provided by a neodymium:yttrium-aluminum garnet laser (532 nm, 550 mJ, 8-ns Spectra Physics GCR-230–10). PSII samples at 1.1 mg of Chl ml−1 were loaded in the dark into quartz EPR tubes and dark-adapted for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the samples were synchronized in the S1 state with one pre-flash (34). After a further 1-h dark adaptation at room temperature and the addition of 0.5 mm PPBQ dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide, the samples were either frozen immediately to 198 K in a solid CO2/ethanol bath or illuminated by one or two additional flashes to generate the S2 and S3 states before being frozen in the dark to 198 K and then transferred to 77 K. In both cases, the samples were degassed at 198 K prior to the recording of the spectra.

For time-resolved measurements at room temperature, the spectrometer was equipped with a Super High Quality Bruker cavity. Saturating laser flash illumination at room temperature was provided by the laser described above. PSII at 1.1 mg of Chl ml−1 was loaded into a small volume flat cell (100 μl) in the presence of 0.5 mm phenyl-p-benzoquinone (PPBQ) and 1 mm potassium ferricyanide. Ferricyanide was added to avoid any contamination from the PPBQ˙̄ signal, which is detectable in the hundred μs time range after the flash illumination in the absence of ferricyanide. Formation and decay of the signal following laser flash illumination were measured at 32 magnetic field positions spread over 50 G and centered on the TyrZ• EPR signal. For each of the 32 magnetic field values, 16 scans were averaged. The two-dimensional spectra (time versus field) of ∼12–16 samples were averaged. Half of the two-dimensional spectra were obtained by increasing the magnetic field, and the other half were obtained by decreasing the magnetic field. When indicated, near-IR illumination of the samples was done directly in the EPR cavity and was provided by a laser diode emitting at 820 nm (Coherent, diode S-81-1000C) with a power of 600–700 milliwatts at the level of the sample.

The High Field-EPR measurements were taken on a locally built spectrometer described previously (35). Using a manganese-doped magnesium oxide sample, we verified that the relative accuracy of the magnetic field was better than 1 millitesla in the field ranges used in this study. The microwave frequency was accurate to better than 1 MHz. Hence, the measurement accuracy in g was expected to be 1 × 10−4.

UV-visible Absorption Change Spectroscopy

Absorption changes were measured with a lab-built spectrophotometer (36) where the absorption changes are sampled at discrete times by short flashes. These flashes were provided by a neodymium:yttrium-aluminum garnet (355 nm) pumped optical parametric oscillator, which produces monochromatic flashes (1 nm full-width at half-maximum) with a duration of 5 ns. Excitation was provided by a second neodymium:yttrium-aluminum garnet (532 nm) pumped optical parametric oscillator, which produces monochromatic saturating flashes at 700 nm (1 nm full-width at half-maximum) with a duration of 5 ns. The path length of the cuvette was 2.5 mm. PSII was used at 25 μg of Chl ml−1 in 10% glycerol, 1 m betaine, 15 mm CaCl2, 15 mm MgCl2, and 40 mm MES (pH 6.5). PSIIs were dark-adapted for ∼1 h at room temperature (20–22 °C) before the additions of 0.1 mm PPBQ dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. For kinetic measurements, the time delay between the actinic flash and the detector flash was first increased from the smaller value to the larger value and then varied in the opposite direction. For each time delay, the measurements were repeated four times so that each data point is the average of eight measurements. The traces shown are typical of those obtained with at least three different PSII preparations.

RESULTS

The oxygen evolution activity of purified PsbA2-PSII was 3000–3500 μmol of O2 (mg of Chl)−1 ml−1. This activity is close to that found for PsbA1-PSII and about half of that commonly found for PsbA3-PSII (33).

Fig. 2 shows the amplitude of the absorption changes associated with each flash in a series with PsbA3-PSII (circles) and with PsbA2-PSII (squares). Measurements were done at 292 nm (37–39) and at 200 ms after the flashes, i.e. after completion of the reduction of TyrZ by the water-oxidizing complex. At this wavelength, the reduction of PPBQ does not lead to any absorption changes, and the successive oxidation steps of the water-oxidizing complex have significant extinction coefficients (38). The pattern, oscillating with a period of four, is clearly observed for both types of PSII preparations with very similar amplitude on the first flash. However, the damping is larger in PsbA2-PSII than in PsbA3-PSII. Indeed, the maxima are clearly shifted from the 5th, 9th, 13th, etc., flashes in PsbA3-PSII to the 6th, 10th, 14th, etc., flashes in PsbA2-PSII. This is at variance with the PsbA(1/3) cases, which displayed similar period four oscillation characteristics like the miss parameter and S1/S0 ratio in dark-adapted material (33, 39, 40). This suggests that functional differences exist between PsbA2-PSII and PsbA(1/3)-PSII.

FIGURE 2.

Sequence of amplitude of absorption changes at 292 nm. The measurements were done during a series of saturating flashes (spaced 200 ms apart) given to dark-adapted PsbA3-PSII (black circles) or PsbA2-PSII (red squares). The samples ([Chl] = 25 μg ml−1) were dark-adapted for 1 h at room temperature before the addition of 100 μm PPBQ. The measurements were done 200 ms after each flash.

To determine which step(s) is(are) kinetically affected and therefore responsible for the larger miss parameter in PsbA2-PSII, we first measured the absorption changes at 292 nm in the 10 μs to ms time ranges after the first three flashes in a series to assess the kinetics of electron transfer associated with the S1TyrZ• → S2TyrZ, S2TyrZ• → S3TyrZ and S3TyrZ• → S0TyrZ transitions in both the PsbA2-PSII and the PsbA3-PSII. At 292 nm, the absorption changes associated with the S2TyrZ• → S3TyrZ transition are small and preclude a reliable kinetic analysis. As shown in Fig. 3, we did not observe any significant differences for the kinetics of the absorption changes associated with the S1TyrZ• → S2TyrZ and S3TyrZ• → S0TyrZ transitions in PsbA2-PSII (squares) when compared with PsbA3-PSII (circles). Thus, the larger miss parameter in PsbA2-PSII does not originate from a longer lifetime of the SiTyrZ•. In addition, we note that the light-induced absorption changes associated with the formation of the S2 state were similar in PsbA2-PSII and PsbA3-PSII. This suggests a similar efficiency for the S1 to S2 transition. We aimed at verifying this conclusion by EPR spectroscopy that provides an exquisitely specific spectrum for the S1 to S2 transition.

FIGURE 3.

Kinetics of absorption changes at 292 nm after first flash (red), second flash (blue), and third flash (black) given to dark-adapted PsbA3-PSII (circles and continuous lines) or PsbA2-PSII (squares and dashed lines). Other experimental conditions were similar to those in Fig. 2.

Fig. 4A shows the difference EPR spectra “after-minus-before” flash illumination in PsbA3-PSII (spectrum a) and PsbA2-PSII (spectrum b). After one flash, the characteristic S2 multiline signal centered at g ∼2 and arising from the Mn4CaO5 cluster in the MnIV3MnIII redox state with a spin state S = 1/2 (see Ref. 41 and references therein for a recent discussion) had an identical shape and a similar amplitude in PsbA3-PSII and PsbA2-PSII. In contrast, after two flashes (Fig. 4B), the amplitude of the S2 multiline signal reflecting the fraction of water-oxidizing complex that did not undergo the S2 → S3 transition was larger in PsbA2-PSII (spectrum b) than in PsbA3-PSII (spectrum a). The amplitude of the positive feature seen between 0 and 1000 G and assigned to the spin S = 3 S3 signal (42) was smaller in PsbA2-PSII than in PsbA3-PSII. The temperature used (8.5 K) was not ideal to measure the S3 EPR signal but was chosen to allow the detection of both the S3 and the S2 signals in the same spectrum. The two observations made above point to a lower yield of the S2 to S3 transition in PsbA2-PSII. Although the spectrum in PsbA2-PSII exhibits a larger negative signal in the nonheme iron magnetic field region at ∼1100 G (e.g. Ref. 28), the shape of the signal assigned to S3 was similar in both samples. This, together with the identical multiline signal observed in both samples, shows that the magnetic structure of the Mn4CaO5 cluster is likely unaffected by the substitution of PsbA3 by PsbA2.

FIGURE 4.

Light-minus-dark EPR spectra induced by either one flash (A) or two flashes (B) at room temperature in presence of 0.5 mm PPBQ and recorded on PsbA3-PSII (spectrum a, black) or PsbA2-PSII (spectrum b, red). Sample concentration was 1.1 mg of Chl ml−1. Instrument settings were: modulation amplitude, 25 G; microwave power, 20 milliwatt; microwave frequency, 9.5 GHz; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; and temperature, 8.5 K. The central part of the spectra corresponding to the TyrD• region was deleted.

We conclude from the above data that the larger miss parameter is not due to a longer lifetime of any of the SiTyrZ• states that would result in a larger charge recombination probability. This makes the electron transfer step between P680+⋅ and TyrZ the next candidate. Fig. 5A shows the time-resolved flash-induced absorption changes around 433 nm after each of the first five flashes applied to dark-adapted PsbA2-PSII (first flash, black; second flash, blue; third flash, red; fourth flash, green; fifth flash, orange). The spectra were recorded 20 ns after the flashes to avoid any spectral distortions due to the short lived excited state, like uncoupled Chl*, for example. In this spectral region, the redox changes of several species, such as the Chls, cytochromes, TyrZ, and QA, could potentially contribute to the absorption changes. The most prominent ones, however, are those associated with the formation of P680+⋅. The P680+⋅/P680 difference spectrum is characterized by a strong Soret band bleaching. After one flash, i.e. in the S1P680+⋅ state, the maximum of the bleaching was observed at 433 nm. After the second flash and third flash, i.e. in the S2P680+⋅ state and S3P680+⋅ state, the width of the bleaching increased, and the red-most parts of the spectra were slightly red-shifted when compared with the spectrum of the S1P680+⋅ state. The red-shift was reversed after the fourth and fifth flashes, i.e. in the S0P680+⋅ and S1P680+⋅ states. This period four oscillation pattern in the P680+⋅/P680 spectrum likely originates from an electrostatic effect on the PD1+⋅PD2⇔PD1PD2+⋅ equilibrium due to the charge(s) stored on/around the Mn4CaO5 cluster (e.g. Ref. 4). Irrespective of the flash number, the difference spectra were similar to those in PsbA1-PSII (40) and PsbA3-PSII (33), thus showing that the distribution of the cation over the PD1 and PD2 chlorophylls is similar in both cases.

FIGURE 5.

A, difference spectra around 430 nm. The flash-induced absorption changes were measured at 20 ns in PsbA2-PSII after the first five flashes given on dark-adapted PsbA2-PSII (first flash, black; second flash, blue; third flash, red; fourth flash, green; fifth flash, orange). [Chl] = 25 μg ml−1. B, kinetics of P680+⋅ reduction measured at 433 nm after the first three flashes in PsbA3-PSII (filled circles) and PsbA2-PSII (open circles). Black circles, first flash; blue circles, second flash; red circles, third flash.

Fig. 5B shows the decay of P680+⋅ measured at 433 nm after each of the first three flashes in PsbA3-PSII (filled circles) and PsbA2-PSII (open circles). After the first flash (black symbols), both the tens of ns and the tens of μs phases were found comparable in PsbA3-PSII and PsbA2-PSII in terms of amplitude and t½. After the second flash (blue symbols) and the third flash (red symbols), the P680+⋅ decay was much slower in PsbA2-PSII, particularly in the hundreds of μs time domain. This shows up even more clearly after averaging the decay traces from the 1st flash to the 20th flash (supplemental Fig. S6).

The finding that the reduction kinetics of P680+⋅ is hardly affected on the first flash shows that possible changes of the properties of the electron acceptor side originating from the PsbA(1/3) to PsbA2 substitution did not significantly increase the percentage of centers in which the P680+⋅QA˙̄ charge recombination occurred, at least with QB in the oxidized state. In addition, the presence of PPBQ prevents the formation of stable QB˙̄ so that the acceptor side is in the same redox state after each flash in the series. Therefore, it is very unlikely that the slower P680+⋅ reduction detected on the second and following flashes originates from a more efficient charge recombination in PsbA2-PSII.

According to the current understanding of the multiphasicity of the reduction of P680+⋅, the ns components are kinetically limited by the electron transfer process, whereas the μs phases involve proton-coupled transfer reactions (e.g. Refs. 43–45). In this framework, the present data would thus point to a slower proton transfer process in PsbA2-PSII. Two amino acid substitutions on the electron donor side of PsbA2-PSII may affect the orientation of the helices, which respectively bear His-190 and TyrZ•: the C144P and P173M exchanges. These two substitutions may impact the hydrogen bond between TyrZ and His-190 and/or the H-bond network in which these two residues are involved. If such is indeed the case, this would be expected to affect the rates of the proton transfer steps associated with the oxidation of TyrZ. This was assessed using EPR spectroscopy, which has been shown to probe the geometry and the environment of the TyrZ phenol ring (e.g. Refs. 46 and 47).

In the S3 state, NIR illumination at ∼4 K results in the formation of a split EPR signal (48, 49), attributed to a (S2TyrZ•)′ state formed by NIR-induced conversion of the manganese cluster into an “activated” state able to oxidize TyrZ and thus leading to the formation of (S2TyrZ•)′ at the expense of the S3TyrZ state (50). This split signal is attributed to the magnetic interaction between TyrZ•, with a spin state S = 1/2 and the Mn4CaO5 cluster possibly in a S = 7/2 spin state (51), and as such is very sensitive to the geometry of the TyrZ•/Mn4CaO5 ensemble. As an example of this sensitivity, the split EPR spectrum is significantly modified upon the Ca2+/Sr2+ exchange (52). Importantly, these modifications can be reliably ascribed to changes in the geometry of the bridge between TyrZ and Ca2+/Sr2+ via a water molecule (3) rather than to the alteration of the Mn4CaO5 magnetic structure, which has been independently shown to be only slightly affected by the Ca2+/Sr2+ exchange (41).

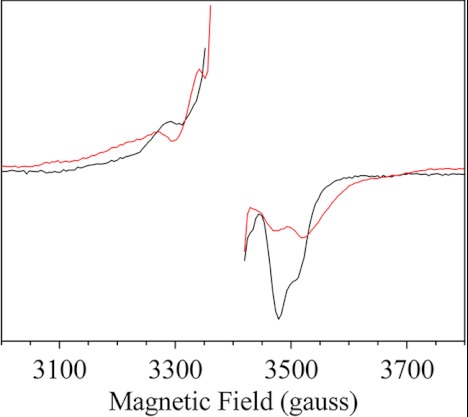

Fig. 6 shows the EPR difference spectra after-minus-before near-infrared illumination in PsbA2-PSII (red spectrum), which are compared with that recorded in PsbA3-PSII (black spectrum). Notably, either PsbA1-PSII or PsbA3-PSII can be used as control samples because their split signals are identical (40, 49, 52). Fig. 6 evidences manifest differences between the two samples. Because the PsbA exchange does not modify the EPR properties of the Mn4CaO5 cluster, at least in the S2 and S3 states, the changes in the split signal likely arise from a change in the EPR properties of TyrZ• or in the magnetic interaction between TyrZ• and the Mn4CaO5 cluster. The EPR properties of TyrZ• that may be modified are: (i) the values and localization of the spin densities on the carbons and oxygen bearing this spin density; (ii) the orientation of the β-methylene group versus the plan of the phenol ring; (iii) the gx, gy, and gz values; (iv) the relative orientation of TyrZ• versus the Mn4CaO5 cluster; and (v) the distance between TyrZ• and the Mn4CaO5 cluster. The changes in the magnetic interaction between TyrZ• and the Mn4CaO5 cluster could be assessed by a theoretical approach. Nevertheless, although some of the split signals, in acetate-treated PSII or in the S1TyrZ• generated at 4 K, have been successfully simulated (53, 54), the magnetic properties of the Mn4 moiety are poorly understood in the S3 state, which precludes here a reliable simulation. Thus, to gain further insights into the structural reasons underlying these spectroscopic changes, we attempted to measure directly the EPR spectrum or TyrZ•.

FIGURE 6.

NIR-induced split EPR spectra in PsbA3-PSII (black spectrum) and PsbA2-PSII (red spectrum). For the two samples, a spectrum was first recorded after two flashes given at room temperature, and a second spectrum was recorded after a further NIR illumination given in the EPR cavity at 4.2 K. Instrument settings were: modulation amplitude, 25 G; microwave power, 20 milliwatt; microwave frequency, 9.5 GHz; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; and temperature, 4.2 K. The chlorophyll concentration was 1.1 mg ml−1. The center part corresponding to the TyrD• spectrum was deleted.

Figs. 7–9 report the results of time-resolved EPR experiments performed at room temperature. The time resolution of our EPR spectrometer is in the same time range as the lifetime of S3TyrZ• in WT T. elongatus PSII (t½ ∼1 ms). To circumvent this limitation, Ca2+ and Cl− were substituted by Sr2+ and Br− in PsbA3-PSII because it has been shown that this markedly increases the lifetime of S3TyrZ• (39). In such conditions, the S3TyrZ• to S0TyrZ transition occurs with a t½ close to 7 ms (39), i.e. in a time domain compatible with the reliable detection of TyrZ• decay with our EPR set-up. Because in separate experiments (not shown) we checked that the Cl−/Br− exchange had no effect on the TyrZ• spectrum and because the Ca2+/Sr2+ exchange alone proved sufficient to allow us the full detection of the TyrZ• signal, the formation and decay of the TyrZ• signals following laser flash illumination were done in Sr2+-containing PsbA2-PSII. These measurements were done at 32 magnetic field positions spread over 50 G and centered on the TyrZ• EPR spectrum.

FIGURE 7.

A, formation and decay of the Tyr• signal following laser flash illumination of manganese-depleted PsbA3-PSII measured at 32 magnetic field positions spread over 50 G from 3486 to 3536 G. For each of the 32 magnetic field values, 16 scans were averaged. The two-dimensional spectra (time versus field) of ∼12–16 samples were averaged. Half of the two-dimensional spectra was obtained by increasing the magnetic field, and the other half was obtained by decreasing the magnetic field. Other instrument settings; modulation amplitude, 4 G; microwave power, 20 milliwatt; microwave frequency, 9.7 GHz; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; and temperature, 293 K. The chlorophyll concentration was 1.1 mg ml−1. Sampling time was 500 μs. B, TyrD• (black) and TyrZ• (red) spectra extracted from the two-dimensional spectrum in panel A. The TyrD• spectrum is the envelope of the baseline before the flash, and the TyrZ• spectrum was obtained by extracting the first slice after the flash (i.e. ∼1 ms) after subtraction of the baseline before the flash, which corresponds to the TyrD• spectrum.

FIGURE 8.

A, formation and decay of the Tyr• signal following laser flash illumination of Sr/Br-PsbA3-PSII. The same protocol as in panel A of Fig. 7 was followed. B, spectra extracted from the two-dimensional spectra as explained for panel B of Fig. 7. The black spectrum corresponds to the TyrZ• spectrum of manganese-depleted PsbA3-PSII, the red spectrum with a continuous line corresponds to the TyrZ• spectrum of Sr/Br-PsbA3-PSII, and the red spectrum with a dashed line corresponds to the TyrZ• spectrum of Sr/Br-PsbA3-PSII with an amplitude multiplied by four.

FIGURE 9.

Black spectrum corresponds to the TyrZ• spectrum of Sr/Br-PsbA3-PSII, and red spectrum with a dashed line corresponds to the TyrZ• spectrum of Sr-PsbA2-PSII. Both spectra were extracted from a two-dimensional spectrum as explained above and correspond to the same Chl concentration and TyrD• signal amplitude.

To validate the approach, we first applied the method to manganese-depleted PSII in which the lifetime of TyrZ• is much longer. Fig. 7A shows the results of such experiments, i.e. a two-dimensional spectrum (time versus field). Fig. 7B shows two slices extracted from the two-dimensional spectrum. The first one (black spectrum), before the flash, corresponds to the TyrD• spectrum, and the second one (red spectrum), immediately after the flash and after subtraction of the baseline for each magnetic field value, corresponds to the TyrZ• spectrum. Although the magnetic field resolution is here limited to 50/31 ∼1.6 G, the TyrD• and TyrZ• spectra thus obtained are similar to those reported in the literature for manganese-depleted PSII (e.g. Refs. 46 and 55).

Fig. 8A shows the results of a similar two-dimensional experiment performed in Sr/Br-containing PsbA3-PSII. Here, in contrast to the situation prevailing in manganese-depleted PSII, the TyrZ• signal was kinetically detectable only in the S3TyrZ• to S0TyrZ transition. In addition, because 16 consecutive flashes were averaged for each sample, the amplitude of the TyrZ• signal should be at most one-fourth of that detected in manganese-depleted PSII in which almost one TyrZ• species is detectable upon each flash. Fig. 8B shows the TyrZ• spectrum recorded in manganese-depleted PSII in Fig. 7 (black spectrum) and the TyrZ• spectrum recorded immediately after the flash in Sr/Br-containing PsbA3-PSII (red spectrum, solid line). The latter has been multiplied 4-fold (dashed red line) to ease its comparison with the manganese-depleted case. Within experimental accuracy, the TyrZ• spectrum in the (S3TyrZ•)′ state was found identical to the TyrZ• spectrum in manganese-depleted PSII. In addition, we did not find any significant changes in the shape of the TyrZ• spectrum occurring while it decays (see supplemental Figs. S3 and S4).

Finally, the two-dimensional EPR experiment was performed in Sr-containing PsbA2-PSII. Fig. 9 compares the TyrZ• spectra detected in PsbA3-PSII (black spectrum) and that recorded in PsbA2-PSII (red spectrum) and evidences small but significant differences between the PsbA2-PSII and PsbA3-PSII TyrZ• spectra in the (S3TyrZ•)′.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe for the first time the construction of a T. elongatus mutant in which both the psbA1 and the psbA3 genes have been deleted, so thus the mutant expresses only the psbA2 gene. The O2-evolving activity of PSII purified from this strain is close to that measured with PsbA1-PSII (∼3500 μmol of O2 (mg of Chl)−1 h−1) and approximately half of that found for PsbA3-PSII (∼6000 μmol of O2 (mg of Chl)−1 h−1). In the current understanding, the limiting step of the overall oxygen evolution in vitro is the exchange of the doubly reduced QBH2 molecule by an oxidized one. Thus, these different oxygen-evolving activities may stem from amino acid substitutions located close to the quinone binding sites. For example, in the x-ray three-dimensional structure of PsbA1-PSII5 (3), S270 and C212 locate close to the QB binding site (supplemental Fig. S1). S270 is replaced by an alanine in both PsbA2-PSII and PsbA3-PSII, and C212 is by replaced by an alanine in PsbA2-PSII and a serine in PsbA3-PSII. However, sequence alignment does not permit the identification of other amino acids that would account for, on the one hand, the similarity between PsbA1-PSI and PsbA2-PSII and, on the other hand, the dissimilarities between these two and PsbA3-PSII. Probably, several amino acid substitutions between PsbA1-PSII, PsbA2-PSII, and PsbA3-PSII could potentially induce long distance effects acting on the hydrogen bond network, the water molecule network, the binding of lipids, and possibly the fine tuning of the interactions between the D1/D2 α-helices.

The C144P and P173M exchanges are two of the less conservative differences between PsbA2 and PsbA(1/3). In PsbA1 and PsbA3, the C144 is located in helix C on the periplasmic side just before the α-helix bearing TyrZ (the Y161), and the P173 is located in the loop between the C and D helices bearing TyrZ and the H190 (3) (see supplemental data). Many studies have documented the role and importance of this H-bond in determining the reaction pathway as well as the rate of the proton-coupled electron transfer process involved associated with the oxidation of TyrZ (e.g. Refs. 26, 30, and 31). Because its ϕ backbone dihedral angle is locked, proline is a singularly rigid amino acid. Its substitution for and by other residues in the vicinities of TyrZ and H190 is expected to have significant structural consequences on the local environment of TyrZ and therefore on this proton-coupled electron transfer. Therefore, it seems very likely that these substitutions have some consequences on the relative orientation of the TyrZ versus H190 and are therefore responsible for the changes reported in this work.

The period four oscillating pattern in PsbA2-PSII indicates that the miss parameter is larger than in either PsbA3-PSII (33, 39) or PsbA1-PSII (40) (Fig. 2). However, the yield of S2 formation estimated from the amplitude of the S2 EPR multiline signal was identical in PsbA2-PSII and PsbA3-PSII, thus showing that the yield of the S1 to S2 transition is not significantly affected (Fig. 4). In contrast, the smaller amplitude of the absorption change detected upon the second flash and the smaller S3 EPR signal and the larger fraction of remaining S2 multiline signal detected after two flashes applied to PSII centers synchronized in the S1 state prior to the flash illumination suggest that in PsbA2-PSII, the miss parameter strongly increases in the S2 to S3 transition. The fact that the miss parameter depends on the S state transitions decreases the accuracy of a fitting of the period four oscillations in Fig. 2 (nevertheless, see supplemental Fig. S7 for a tentative fitting procedure). Based on the fraction of the remaining S2 multiline signal, we estimate this increase to be 2-fold (i.e. ∼20%).

The S2 EPR multiline spectra and S3 EPR spectra are known as being exquisitely sensitive to the structure and spin distribution within the cluster (41, 42). On the contrary, the absence of significant differences between these spectroscopic features obtained in the PsbA2-PSII and PsbA3-PSII show that the structure of the Mn4CaO5 is very likely not affected by the PsbA exchange. In addition, the P680+⋅/P680 difference spectra versus the flash number in PsbA2-PSII do not reveal any significant changes in the charge distribution over the PD1PD2 chlorophyll dimer because the spectra after one, two, or three flashes have a maximum bleaching at 433 nm as in PsbA1-PSII and PsbA3-PSII. Therefore, it seems likely that the increase of the miss parameter reported above originates from a modification of TyrZ itself. Indeed, several authors have pointed to the electron transfer between TyrZ and P680 as being an important contributor to the miss parameter (for example, see Refs. 56–58 for discussions).

The similar kinetics observed for the S1TyrZ• to S2TyrZ transition (t½ ∼50 μs), for whichever PsbA protein is involved, is consistent with an unmodified miss parameter on this transition. In the S3TyrZ• to S0TyrZ transition, the decay of the ΔI/I at 292 nm is biphasic (Fig. 3). The fast phase (t½ ∼100 μs) seen as a lag phase at 292 nm has been interpreted as reflecting the electrostatically triggered expulsion of one proton from the catalytic center caused by the positive charge near/on TyrZ• (59). The slow phase, attested by an absorption decay with t½ ∼1 ms, corresponds to the formation of S0 and O2 and to an additional proton release (Refs. 59–63), and see also Ref. 64 for a recent work dealing with this these two phases in T. elongatus). From data in Fig. 3, neither the lag phase S3TyrZ• to (S3TyrZ•)′ nor the (S3TyrZ•)′ to S0TyrZ transition seems affected by the PsbA exchange.

For the S2TyrZ• to S3TyrZ transition, in which EPR measurements clearly indicate an increase of the miss parameter, the measurements at 292 nm are unfortunately not very informative. Thus, to probe further the TyrZ environment, we measured the reduction of P680+⋅. As previously observed by many groups (see below), this kinetics has multiple components. The fast ones have been interpreted as being kinetically limited by the electron transfer process and were similar in rates in the various samples. The phases developing in the μs to tens of μs time range have been interpreted as being kinetically limited by proton transfer, and these were markedly affected by the PsbA3 to PsbA2 exchange, in particular after the second and third flashes in the series. These components were slower, and their amplitudes were larger in PsbA2-PSII. This, together with the modified split EPR signal detected upon NIR illumination in PsbA2-PSII, shows that TyrZ is indeed the cofactor with modified properties in PsbA2-PSII. Before discussing these structural issues, we would like to note that as a side result of the present study, we report here the first TyrZ• EPR spectrum in the (S3TyrZ•)′ state in active PSII. We show that it is similar to that in manganese-depleted PSII. From W-band EPR, the geometry of TyrZ• in manganese-depleted PSII crystals was found to be similar to that expected from the geometry of TyrZ in the dark-adapted state of Mn4CaO5-containing crystal (65). Thus, the geometry of TyrZ• in the (S3TyrZ•)′ state is also likely similar to that of TyrZ in the S1 state.

Several structural reasons may be considered to account for the different properties of TyrZ. One is a change in the orientation of the TyrZ• radical with respect to the Mn4CaO5 cluster that would modify the magnetic interaction between TyrZ• and the Mn4CaO5 cluster. To further assess this, we attempted to characterize the g-tensor of TyrZ• by high field EPR. We note, however, that this study was performed with manganese-depleted PsbA2-PSII (supplemental Fig. S5), so its conclusions cannot be straightforwardly extrapolated to oxygen-evolving PSII. Although small, the changes indicate without ambiguities that the gx resonance of the TyrZ• spectrum was broader and likely up-shifted. This could explain the modified X-band EPR spectrum measured in the (S3TyrZ•)′ state. An up-shift of the gx value is indicative of a less positive electrostatic environment for TyrZ• (47). The changes in the hyperfine structure of the time-resolved TyrZ• spectrum in the (S3TyrZ•)′ state are also reminiscent of that observed in the TyrD• spectrum in the D2-H189L mutant that disrupts the H-bond in which TyrD• is involved (47). Altogether these data thus point to a weaker H-bond between TyrZ and H190.

The data above indicate that the main modifications on the electron donor side of PsbA2-PSII occur at the level of TyrZ. This could be a consequence of the C144P and P173M exchanges, which in turn would modify the H-bond between TyrZ and H190. It is indeed widely agreed that the proton-coupled electron transfer rates for the Tyr oxidation depend on the properties of the Tyr-O···H···N-His bonding (e.g. Refs. 26, 31, and 66). It has indeed been shown that, in model compounds, the proton-coupled electron transfer rate from a tyrosine to an oxidant was strongly dependent on the intramolecular distance between the tyrosine and the base that accepts the proton (e.g. Ref. 67). Interestingly, the hydrogen bond between the phenol group of TyrZ and the Nϵ of H190 in PSII is very short (2.46 Å in Ref. 3). Recently, the rationale underlying this short H-bond has been investigated by a quantum mechanical-molecular mechanical approach (68), and the cluster of four water molecules involved in the Mn4CaO5-TyrZ motif has been shown to play an important role in the stabilization of such a short distance. In this framework, it would not be surprising that a small distortion of such a delicate scaffold would have important consequences on the oxidation of TyrZ by P680+⋅ and in particular on those steps that are kinetically limited by the proton transfer within the H-bond network in which TyrZ and His-190 are involved.

In contrast to the marked kinetic effects that we observed on the slow components of the oxidation of TyrZ by P680+⋅, the reduction rates of the various SiTyrZ• states were unaffected by the PsbA3 to PsbA2 exchange. As regards the S1 to S2 transition, this is expected because it is only accompanied by substoichiometric proton release (69–71). However, the subsequent S2 to S3 and S3 to S0 electron transfer steps are chemically coupled to proton release (e.g. Refs. 72 and 73) and might be affected by the changes in the H-bond network around TyrZ and His-190 discussed above. To our knowledge, the present study is the only one reporting a slowdown of the μs components in the oxidation of TyrZ besides, of course, the H/D experiments (43, 63, 74). Interestingly, kinetic isotope effects have also been reported for the following electron transfer step, i.e. the reduction of TyrZ•, at least in the presence of the S2 and S3 states. Notably, the most pronounced kinetic isotope effect has been reported to occur during the S3TyrZ• to (S3TyrZ•)′ (63), which is assigned to an electrostatically triggered proton release (59, 63). The present observation that the PsbA3 to PsbA2 exchange affects the μs components in the oxidation of TyrZ• while keeping unaffected the proton release associated with the S3TyrZ• to (S3TyrZ•)′ transition suggests that this particular proton release does not originate from the same H-bond network as the one involved in the proton transfer triggered by the formation of TyrZ•. The latter has been described as a sequence of push-pull steps that would be initiated by the transfer of the phenolic proton from TyrZ to Nϵ of H190. The identity of the “proton releaser” during the S3TyrZ• to (S3TyrZ•)′ is not known, and several candidates have been considered. A substrate water molecule is an obvious one (for example, see Ref. 76 for a model in which both the proton and the electron originate from the substrate water molecule). Alternatively, it could be a protonated base, proposed to be CP43-R357 (77), that would undergo a pKa shift upon the formation of the S3TyrZ•⋯HNϵ(H190)+ state and would, by acting as a proton acceptor from water, promote water splitting. These different proton transfer events thus have essentially different mechanistic implications. Although one mainly reflects electrostatic relaxation, the other sets the stage for all the players in the water-splitting process. In such a framework, it is not surprising that they involve different molecular actors, and the present results support this expectation. Notably, they also point to a necessary conformational change to account for the fact that a new proton releaser that had stayed inactive until the formation of S3 would come into play when S3TyrZ•⋯HNϵ(H190)+ is formed (for example, see Refs. 73 and 75 for experimental evidences of structural changes in the S state cycle).

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7.

Throughout this study, WT*1, WT*2, and WT*3 are used to indicate cells containing only the psbA1, psbA2, and psbA3 gene, respectively.

The structure reported in Ref. 3 is from T. vulcanus and not from T. elongatus, which is used here. However the psbA1 genes, except for the threonine 286 in T. elongatus substituted for an alanine in T. vulcanus, are identical in the two organisms.

- PSII

- photosystem II

- Chl

- chlorophyll

- PPBQ

- phenyl-p-benzoquinone, P680, chlorophyll dimer acting as the second electron donor

- QA

- primary quinone acceptor

- QB

- secondary quinone acceptor

- PheoD1

- pheophytin PD1 and PD2

- NIR

- near-infrared

- PD1 and PD2

- Chl monomers of P680 on the D1 and D2 side, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ferreira K. N., Iverson T. M., Maghlaoui K., Barber J., Iwata S. (2004) Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science 303, 1831–1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guskov A., Kern J., Gabdulkhakov A., Broser M., Zouni A., Saenger W. (2009) Cyanobacterial photosystem II at 2.9-Å resolution and the role of quinones, lipids, channels, and chloride. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Umena Y., Kawakami K., Shen J. R., Kamiya N. (2011) Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature 473, 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diner B. A., Rappaport F. (2002) Structure, dynamics, and energetics of the primary photochemistry of photosystem II of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 53, 551–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Renger G. (2011) Light-induced oxidative water splitting in photosynthesis: energetics, kinetics, and mechanism. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 104, 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groot M. L., Pawlowicz N. P., van Wilderen L. J., Breton J., van Stokkum I. H., van Grondelle R. (2005) Initial electron donor and acceptor in isolated photosystem II reaction centers identified with femtosecond mid-IR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13087–13092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holzwarth A. R., Müller M. G., Reus M., Nowaczyk M., Sander J., Rögner M. (2006) Kinetics and mechanism of electron transfer in intact photosystem II and in the isolated reaction center: pheophytin is the primary electron acceptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6895–6900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crofts A. R., Wraight C. A. (1983) The electrochemical domain of photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 726, 149–185 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Velthuys B. R., Amesz J. (1974) Charge accumulation at the reducing side of system 2 of photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 333, 85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kok B., Forbush B., McGloin M. (1970) Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution-I. A linear four step mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 11, 457–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joliot P., Kok B. (1975) in Bioenergetics of Photosynthesis (Govindjee, ed) pp. 387–412, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clarke A. K., Soitamo A., Gustafsson P., Oquist G. (1993) Rapid interchange between two distinct forms of cyanobacterial photosystem II reaction-center protein D1 in response to photoinhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 9973–9977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Golden S. S. (1995) Light-responsive gene expression in cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 177, 1651–1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Komenda J., Hassan H. A., Diner B. A., Debus R. J., Barber J., Nixon P. J. (2000) Degradation of the photosystem II D1 and D2 proteins in different strains of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 varying with respect to the type and level of psbA transcript. Plant Mol. Biol. 42, 635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sicora C. I., Appleton S. E., Brown C. M., Chung J., Chandler J., Cockshutt A. M., Vass I., Campbell D. A. (2006) Cyanobacterial psbA families in Anabaena and Synechocystis encode trace, constitutive, and UVB-induced D1 isoforms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757, 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kós P. B., Deák Z., Cheregi O., Vass I. (2008) Differential regulation of psbA and psbD gene expression, and the role of the different D1 protein copies in the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mulo P., Sicora C., Aro E. M., (2009) Cyanobacterial psbA gene family: optimization of oxygenic photosynthesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 3697–3710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sicora C. I., Ho F. M., Salminen T., Styring S., Aro E. M. (2009) Transcription of a “silent” cyanobacterial psbA gene is induced by microaerobic conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sugiura M., Kato Y., Takahashi R., Suzuki H., Watanabe T., Noguchi T., Rappaport F., Boussac A. (2010) Energetics in photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus with a D1 protein encoded by either the psbA1 or psbA3 gene. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1797, 1491–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakamura Y., Kaneko T., Sato S., Ikeuchi M., Katoh H., Sasamoto S., Watanabe A., Iriguchi M., Kawashima K., Kimura T., Kishida Y., Kiyokawa C., Kohara M., Matsumoto M., Matsuno A., Nakazaki N., Shimpo S., Sugimoto M., Takeuchi C., Yamada M., Tabata S. (2002) Complete genome structure of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1. DNA Res. 9, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loll B., Broser M., Kós P. B., Kern J., Biesiadka J., Vass I., Saenger W., Zouni A. (2008) Modeling of variant copies of subunit D1 in the structure of photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus. Biol. Chem. 389, 609–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sander J., Nowaczyk M., Buchta J., Dau H., Vass I., Deák Z., Dorogi M., Iwai M., Rögner M. (2010) Functional characterization and quantification of the alternative PsbA copies in Thermosynechococcus elongatus and their role in photoprotection. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29851–29856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kato Y., Sugiura M., Oda A., Watanabe T. (2009) Spectroelectrochemical determination of the redox potential of pheophytin a, the primary electron acceptor in photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17365–17370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Merry S. A., Nixon P. J., Barter L. M., Schilstra M., Porter G., Barber J., Durrant J. R., Klug D. R. (1998) Modulation of quantum yield of primary radical pair formation in photosystem II by site-directed mutagenesis affecting radical cations and anions. Biochemistry 37, 17439–17447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cuni A., Xiong L., Sayre R. T., Rappaport F., Lavergne J. (2004) Modification of the pheophytin midpoint potential in photosystem II: modulation of the quantum yield of charge separation and of charge recombination pathways. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 4825–4831 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rappaport F., Boussac A., Force D. A., Peloquin J., Brynda M., Sugiura M., Un S., Britt R. D., Diner B. A. (2009) Probing the coupling between proton and electron transfer in photosystem II core complexes containing a 3-fluorotyrosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4425–4433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sugiura M., Iwai E., Hayashi H., Boussac A. (2010) Differences in the interactions between the subunits of photosystem II dependent on D1 protein variants in the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30008–30018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boussac A., Sugiura M., Rappaport F. (2011) Probing the quinone binding site of photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus containing either PsbA1 or PsbA3 as the D1 protein through the binding characteristics of herbicides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ogami S., Boussac A., Sugiura M. (February 2, 2012) Deactivation processes in PsbA1-photosystem II and PsbA3-photosystem II under photoinhibitory conditions in the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Debus R. J. (2008) Protein ligation of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 244–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rappaport F., Lavergne J. (2001) Coupling of electron and proton transfer in the photosynthetic water oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1503, 246–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sugiura M., Inoue Y. (1999) Highly purified thermo-stable oxygen-evolving photosystem II core complex from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus having His-tagged CP43. Plant Cell Physiol. 40, 1219–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sugiura M., Boussac A., Noguchi T., Rappaport F., (2008) Influence of histidine-198 of the D1 subunit on the properties of the primary electron donor, P680, of photosystem II in Thermosynechococcus elongatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 331–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Styring S., Rutherford A. W. (1987) In the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II the S0 state is oxidized to the S1 state by D+ (Signal-II slow). Biochemistry 26, 2401–2405 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Un S., Dorlet P., Rutherford A. W. (2001) A high field EPR tour of radicals in photosystems I and II. Appl. Magn. Reson. 21, 341–361 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beal D., Rappaport F., Joliot P. (1999) A new high sensitivity 10-ns time-resolution spectrophotometric technique adapted to in vivo analysis of the photosynthetic apparatus. Rev Sci Instrum. 70, 202–207 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lavergne J. (1984) Absorption changes of photosystem II donors and acceptors in algal cells FEBS Lett. 173, 9–14 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lavergne J. (1991) Improved UV-visible spectra of the S-transitions in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1060, 175–188 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ishida N., Sugiura M., Rappaport F., Lai T. L., Rutherford A. W., Boussac A. (2008) Biosynthetic exchange of bromide for chloride and strontium for calcium in the photosystem II oxygen-evolving enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13330–13340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sugiura M., Rappaport F., Brettel K., Noguchi T., Rutherford A. W., Boussac A., (2004) Site-directed mutagenesis of Thermosynechococcus elongatus photosystem II: the O2-evolving enzyme lacking the redox-active tyrosine D. Biochemistry 43, 13549–13563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cox N., Rapatskiy L., Su J. H., Pantazis D. A., Sugiura M., Kulik L., Dorlet P., Rutherford A. W., Neese F., Boussac A., Lubitz W., Messinger J. (2011) Effect of Ca2+/Sr2+ substitution on the electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: a combined multifrequency EPR, 55Mn-ENDOR, and DFT study of the S2 state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 3635–3648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Boussac A., Sugiura M., Rutherford A. W., Dorlet P. (2009) Complete EPR spectrum of the S3 state of the oxygen-evolving photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5050–5051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schilstra M. J., Rappaport F., Nugent J. H., Barnett C. J., Klug D. R. (1998) Proton/hydrogen transfer affects the S state-dependent microsecond phases of P680+ reduction during water splitting. Biochemistry 37, 3974–3981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuhn P., Eckert H., Eichler H. J., Renger G. (2004) Analysis of the P680+⋅ reduction pattern and its temperature dependence in oxygen-evolving PSII core complexes from a thermophilic cyanobacteria and higher plants. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 4838–4843 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Christen G., Renger G. (1999) The role of hydrogen bonds for the multiphasic P680+⋅ reduction by YZ in photosystem II with intact oxygen evolution capacity: analysis of kinetic H/D isotope exchange effects. Biochemistry 38, 2068–2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tommos C., Tang X. S., Warncke K., Hoganson C. W., Styring S., McCracken J., Diner B. A., Bancock G. T. (1995) Spin-density distribution, conformation, and hydrogen-bonding of the redox-active tyrosine Y-Z in photosystem II from multiple electron magnetic-resonance spectroscopies: implications for photosynthetic oxygen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 10325–10335 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Un S., Boussac A., Sugiura M. (2007) Characterization of the tyrosine-Z radical and its environment in the spin-coupled S2TyrZ• state of photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus. Biochemistry 46, 3138–3150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ioannidis N., Petrouleas V. (2000) Electron paramagnetic resonance signals from the S3 state of the oxygen-evolving complex: a broadened radical signal induced by low temperature near-infrared light illumination. Biochemistry 39, 5246–5254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Boussac A., Sugiura M., Kirilovsky D., Rutherford A. W. (2005) Near-infrared-induced transitions in the manganese cluster of photosystem II: action spectra for the S2 and S3 redox states. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 837–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Petrouleas V., Koulougliotis D., Ioannidis N. (2005) Trapping of metalloradical intermediates of the S states at liquid helium temperatures: overview of the phenomenology and mechanistic implications. Biochemistry 44, 6723–6728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sanakis Y., Ioannidis N., Sioros G., Petrouleas V. (2001) A novel S = 7/2 configuration of the manganese cluster of photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 10766–10767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boussac A., Sugiura M., Lai T. L., Rutherford A. W. (2008) Low temperature photochemistry in photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus induced by visible and near-infrared light. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 1203–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dorlet P., Boussac A., Rutherford A. W., Un U. (1999) Multifrequency high field EPR study of the interaction between the tyrosyl Z radical and the manganese cluster in plant photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 10945–10954 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Koulougliotis D., Teutloff C., Sanakis Y., Lubitz W., Petrouleas V. (2004) The S1YZ• metalloradical intermediate in photosystem II: an X- and W-band EPR study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 4859–4863 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mino H., Kawamori A. (1994) Microenvironments of tyrosine D+ and tyrosine Z+ in photosystem II studied by proton matrix ENDOR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1185, 213–220 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shinkarev V. P., Wraight C. A. (1993) Oxygen evolution in photosynthesis: from unicycle to bicycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 1834–1838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lavergne J., Rappaport F. (1998) Stabilization of charge separation and photochemical misses in photosystem II. Biochemistry 37, 7899–7906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. de Wijn R., van Gorkom H. J. (2002) The rate of charge recombination in photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1553, 302–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rappaport F., Blanchard-Desce M., Lavergne J. (1994) Kinetics of electron-transfer and electrochromic change during the redox transitions of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1184, 178–192 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Koike H., Hanssum B., Inoue Y., Renger G. (1987) Temperature dependence of S state transition in a thermophilic cyanobacterium, Synechococcus vulcanus copeland measured by absorption changes in the ultraviolet region. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 893, 524–533 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Razeghifard M. R., Pace R. J. (1999) EPR kinetic studies of oxygen release in thylakoids and PSII membranes: a kinetic intermediate in the S3 to S0 transition. Biochemistry 38, 1252–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Haumann M., Liebisch P., Müller C., Barra M., Grabolle M., Dau H. (2005) Photosynthetic O2 formation tracked by time-resolved x-ray experiments. Science 310, 1019–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gerencsér L., Dau H. (2010) Water oxidation by photosystem II: H2O-D2O exchange and the influence of pH support formation of an intermediate by removal of a proton before dioxygen creation. Biochemistry 49, 10098–10106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rappaport F., Ishida N., Sugiura M., Boussac A. (2011) Ca2+ determines the entropy changes associated with the formation of transition states during water oxidation by Photosystem II Energ. Environ. Sci. 4, 2520–2524 [Google Scholar]

- 65. Matsuoka H., Shen J. R., Kawamori A., Nishiyama K., Ohba Y., Yamauchi S. (2011) Proton-coupled electron-transfer processes in photosystem II probed by highly resolved g-anisotropy of redox-active tyrosine YZ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4655–4660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hays A. M., Vassiliev I. R., Golbeck J. H., Debus R. J. (1999) Role of D1-His-190 in the proton-coupled oxidation of tyrosine YZ in manganese-depleted photosystem II. Biochemistry 38, 11851–11865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang M. T., Irebo T., Johansson O., Hammarström L. (2011) Proton-coupled electron transfer from tyrosine: a strong rate dependence on intramolecular proton transfer distance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13224–13227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Saito K., Shen J. R., Ishida T., Ishikita H. (2011) Short hydrogen bond between redox-active tyrosine YZ and D1-His-190 in the photosystem II crystal structure. Biochemistry 50, 9836–9844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Forster V., Junge W. (1985) Stoichiometry and kinetics of proton release upon photosynthetic water oxidation. Photochem. Photobiol. 41, 183–190 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rappaport F., Lavergne J. (1991) Proton release during successive oxidation steps of the photosynthetic water oxidation process: stoichiometries and pH dependence. Biochemistry 30, 10004–10012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jahns P., Lavergne J., Rappaport F., Junge W. (1991) Stoichiometry of proton release during photosynthetic water oxidation: a reinterpretation of the responses of neutral red leads to a noninteger pattern. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1057, 313–319 [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lavergne J., Junge W. (1993) Proton release during the redox cycle of the water oxidase. Photosynth. Res. 38, 279–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dau H., Haumann H. (2008) The manganese complex of photosystem II in its reaction cycle: basic framework and possible realization at the atomic level. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 273–295 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Christen G., Seeliger A., Renger G. (1999) P680+⋅ reduction kinetics and redox transition probability of the water-oxidizing complex as a function of pH and H/D isotope exchange in spinach thylakoids. Biochemistry 38, 6082–6092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pushkar Y., Yano J., Sauer K., Boussac A., Yachandra V. (2008) Structural changes in the Mn4Ca cluster and the mechanism of photosynthetic water splitting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1879–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Westphal K. L., Tommos C., Cukier R. I., Babcock G. T. (2000) Concerted hydrogen-atom abstraction in photosynthetic water oxidation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 236–242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sproviero E. M., Gascón J. A., McEvoy J. P., Brudvig G. W., Batista V. S. (2008) Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics study of the catalytic cycle of water splitting in photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3428–3442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.