Abstract

Background

The dimensions of local flaps are often limited by the vascular supply to the distal aspect of the flap. Distal flap necrosis occurs if the vascular supply is inadequate. The purpose of this study was to investigate the use of iontophoretic delivery of NO donors to a local skin flap model to improve the survival area of the flap.

Methods

Thirty-two male Sprague-Dawley rats (300g) were divided into 7 experimental groups to determine the effect of iontophoretic delivery of nitric oxide (NO) on surface perfusion and flap survival area. A caudally based 3 x 11 cm dorsal skin flap was used to measure the effect of iontophoretic delivery of NO donors to a local skin flap to improve survival area of the flap.

Results

Iontophoretic delivery of the NO donors’ sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and diethyltriamine NONOate (DETA-NO) resulted in a significant increase in survival area and surface perfusion when compared with sham controls. Iontophoretic delivery of saline was associated with a 13% improvement in flap survival when compared with non-treated controls.

Conclusions

Iontophoretic delivery and subcutaneous injection of NO donors (SNP and DETA-NO) increased skin flap viability by demonstrating improved flap survival areas. The results of this study suggest that NO may serve as a postoperative treatment of skin flaps to encourage skin flap survival and prevent distal necrosis.

Introduction

Local skin flaps are commonly used in the repair of small volume wounds. These local flaps generally have random pattern vascularity and are limited in their dimensions by the perfusion pressure within the supplying subdermal and dermal vascular plexus. The distal aspect of a local random pattern flap has the greatest risk of ischemic necrosis due to the limitations in vascular perfusion. Improvements in flap viability might be seen with manipulations that improve blood supply (i.e., use of vasodilators), decrease tissue damage caused by ischemia (i.e., use of free radical scavengers) or that speed neovascularization (i.e., use of growth factors). Numerous studies have focused on intrinsic and extrinsic manipulations of local flaps to alter these processes. [1–4] External manipulations such as preclamping or preconditioning have been shown to improve flap viability, however the mechanisms associated with these improvements are not well understood. The preclamping method is based on the principle of ischemic preconditioning (IP), which is defined as a brief period of ischemia followed by tissue reperfusion, which is thought to thereby improve ischemic tolerance for a longer period of ischemia.[5] Mounsey et al. [6] was first to examine the positive effects of preclamping, and this technique was then followed by other investigations.[7, 8] A potential mechanism by which preconditioning improves flap survival may involve improved availability of nitric oxide (NO) within the flap tissue after the preconditioning period.[9, 10]

The beneficial impact of NO on tissue flap health has been demonstrated in a number of local flap studies. Supplementation of L-arginine as a substrate of NO has also been shown to significantly reduce necrosis in random pattern flaps,[11] and porcine myocutaneous flaps.[12] Further, the use NO inhibitors significantly increased flap necrosis in the random pattern flaps.[11] However, the clinical utility of NO donors has been limited by the absence of a method to effectively and safely deliver these agents to at-risk local flaps in humans. For example, simple topical application has limited absorption and availability, local injection may be traumatic to flap vasculature, and systemic administration is hampered by dilution and systemic side effects. As such, new methods of promoting increased NO within at-risk tissue should be explored.

A potential method of delivering NO to at-risk tissues is iontophoresis. Iontophoresis involves the use of AC or DC electrical currents to drive the delivery of charged agents through tissues in order to improve delivery of these agents relative to levels delivered via simple diffusion.

Iontophoresis has been used clinically for improved delivery of local anesthetics and steroid treatments. [13, 14] However, it has rarely been used or studied in relation to the treatment of skin flaps.[15] This relative scarcity of investigations is surprising because there is evidence that electrical stimulation can itself affect and improve tissue repair. [16–18] Further, it has been shown that pulsed electrical stimulation can improve the survival of porcine skin flaps.[19]

Therefore iontophoresis was chosen for this study based on three major advantages over passive diffusion: 1) control of penetration can be linked to drug flux by the magnitude of the electrical current. 2) Lag times are reduced or removed making drug action more rapid. 3) Time of administration can be controlled by removal of the iontophresis patch, this cannont be easily accomplished by topical formulations.The focus of this study was to investigate the use of iontophoretic delivery of NO donors to a local skin flap to improve survival area of the flap. We hypothesized that iontophoretic delivery of a NO donor would increase skin flap survival when compared with a nontreated control group.

Methods

Thirty-two male Sprague-Dawley rats (average weight = 318g) were used for this study. In two experiments, animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine (90 mg/kg) and 1% xylazine (9 mg/kg). After shaving and depilating the back, a caudally based 3 x 11 cm dorsal skin flap was elevated with the panniculus carnosus on all 32 rats. [20] All flaps were sutured into place with 4-0 silk and survived for 7 days.

Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and diethyltriamine NONOate (DETA-NO) served as NO donor molecules. The use of these molecules allowed investigation of NO donors with a rapid rate of NO release (SNP) versus a slower release (DETA-NO). Although each pathway leading to NO formation differs among classes, all NO donors produce NO-related activity when applied and are thus well-suited to mimic endogenous NO response.[21]

The 32 rats were divided into 8 groups, and treatments were delivered either via injection (INJ) or transdermal iontophoretic delivery (TID). Groups and specific treatments are shown in Table 1. The treatment groups in this study were:

Table 1.

Groups and treatments used in preliminary study of tissue flap survival as a function of nitric oxide treatment. SNP=sodium nitroprusside; DETA-NO= diethyltriamine NONOate; TID= transdermal delivery; INJ= injection; PBS= phosphate buffered saline.

| Group | N | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 4 | No treatment |

| Saline INJ | 4 | 0.2 mL PBS injection treatment |

| Saline TID | 4 | 1 mL PBS TID treatment |

| SNP TID | 4 | 1 mL solution of either 1.25 mg with PBS |

| SNP TID | 4 | 1 mL solution of 12.5 mg SNP with PBS |

| DETA-NO TID | 4 | 1 mL solution of a 2 mM DETA and PBS |

| SNP INJ | 4 | 0.2 mL injection of 1.25 mg SNP with PBS |

| DETA-NO INJ | 4 | 0.2 mL injection of DETA-NO mixed to 2mM solution in PBS |

Sham Control, where flaps were created, but no treatment was delivered;

Saline TID, to examine the effects of electrical stimulation of the skin 1mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) without NO;

Saline INJ, 0.2 mL PBS as a control for the INJ condition;

SNP TID, 1 mL solution of 1.25 mg SNP with PBS;

SNP TID, 1 mL solution of 12.5 mg SNP with PBS;

SNP INJ, 0.2 mL injection of 1.25 mg SNP with PBS;

DETA-NO TID, 1 mL solution of a 2 mM DETA and PBS; and

DETA-NO INJ, 0.2 mL injection of DETA-NO mixed to 2mM solution in PBS.

Iontophoretic delivery was provided by a commercially available device (Iomed, Phoresor II, PM850; IOMED, Salt Lake City, UT), using a small electrode with an area of 7.5 cm2 (Iogel) with a current of .5 mA/cm2 for 20 minutes.. This dosage was chosen based on the maximum allowable setting without inducing burn or irritation. Injections and placement of the small electrode were made between the 5 and 6 cm mark from the caudal end of the flap. All INJ and TID treatments were given for the first 5 days of the 7-day post treatment period. At 7 days, following flap elevation, all flaps were photographed and planimetry data were analyzed by Simple PCI (Compix, Sewickley, PA). In addition, laser Doppler imaging (LDI) was performed on all flaps (PIM II scanning system, LDPIwin software version 2.0.9, Lisca Development, Linköping, Sweden). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences between treatments in percentage of flap survival and surface perfusion of live tissue using an α-level of .05 to determine statistical significance.

Results

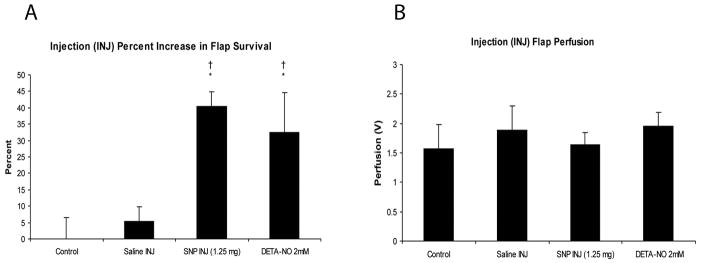

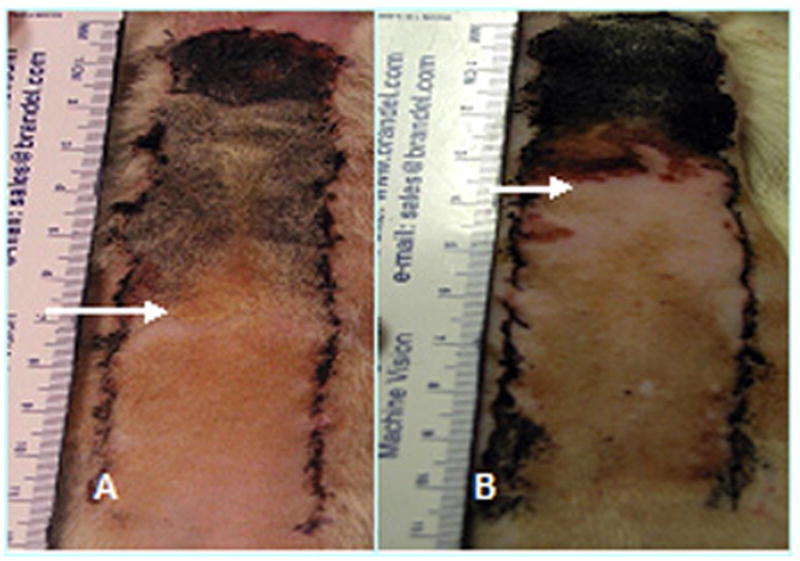

Figure 1 is a representative photograph demonstrating the increased tissue survival following NO donor INJ.Figure 2 summarizes the ability of NO donor injection to augment survival and surface perfusion in rat skin flaps. As shown in Figure 2A, injections of both 1.25 mg of SNP and DETA-NO (2mM) significantly increased survival area by 40 and 33% respectively when compared with both saline INJ and Sham Controls (p=.006 and .0225 respectively). However, neither of the NO donors delivered via injection had a significant effect of surface perfusion, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 1.

Representative photo of increased tissue survival is noted following injection of the NO donor DETA-NO. Arrows designate line of necrosis. (A) Photo of control flap. (B) DETA-NO treated flap. DETA-NO=diethyltriamine NONOate.

Figure 2.

(A) Average percentage increase in survival via injection treatment with and without NO donors. (B) Flap perfusion of the different nitric oxide treatments and control. SNP=sodium nitroprusside; DETA-NO=diethyltriamine NONOate. N=4 per group. Values are means ± SD. † P<.05 vs. Sham control, * P<.05 vs INJ control.

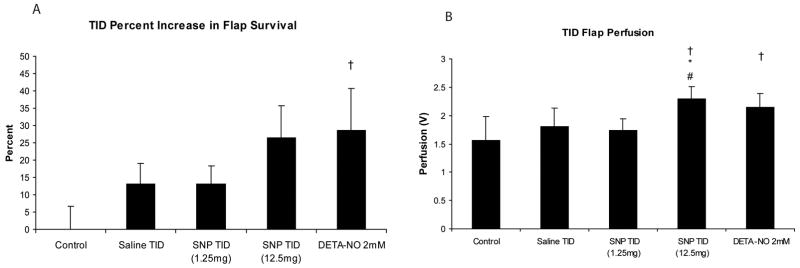

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of transdermal iontophoretic delivery (TID) of SNP and DETA-NO on rat skin survival. A 2 mM concentration DETA-NO TID resulted in a significant increase in survival area and surface perfusion when compared with Sham Controls (p=.01). In contrast to the injection groups, 1.25 mg of SNP with TID did not result in a significant increase in flap survival area when compared with Sham Controls. However, a higher dose of SNP (12.5 mg) TID approached a significant increase in flap survival (p =.059), and a significant increase in surface perfusion of flaps was seen with the higher dose when compared with 1.25 mg of SNP, Sham control, and TID saline groups (p=.02, .002, and .03 respectively).

Figure 3.

(A) Average percentage increase in survival area via TID treatment with and without NO donors.(B) Flap perfusion of the different nitric oxide treatments via TID treatment and control. SNP=sodium nitroprusside; DETA-NO= diethyltriamine NONOate. N=4 per group. Values are means ± SD.. † P<.05 vs. SHAM, * p<.05 vs. INJ Control, # P< .05 vs. SNP 1.25 mg (TID).

Confirming the utility of electrical stimulation alone, the TID saline group had a 13% improvement in flap survival when compared with non-treated controls. More importantly, DETA-NO delivered via TID more than doubled the improvements in survival area seen with electrical stimulation alone (TID saline group).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess whether administration of a NO donor through transdermal delivery would augment local skin flap survival. We observed that iontophoretic delivery and subcutaneous injection of NO donors (SNP and DETA-NO) increased skin flap viability by demonstrating improved flap survival areas. These findings allowed us to accept our hypothesis that iontophoretic delivery of NO donor may increase skin flap survival.

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of transdermal iontophoretic delivery (TID) and injection (INJ) of NO donors in improving local flap surface perfusion and survival. In addition, although not a statistically significant increase, there was a 13% increase in survival area with electrical stimulation alone (TID saline), suggesting that electrical stimulation may promote skin flap survival. Although injection of NO donors proved beneficial, an injection mode of administration might not be clinically useful due to concerns that the injections themselves could produce trauma to the delicate subdermal and dermal vascular plexus of local flaps. The use of TID would eliminate this potential hazard.

Our results are consistent with prior studies that suggest that NO positively impacts the wound healing process at several levels. NO is a mediator of angiogenesis by enhancing endothelial cell proliferation, perhaps in part by increasing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or fibroblast growth factor (bFGF).[22–24] Nitric Oxide also enhances endothelial migration.[25, 26] Finally, the hemodynamic effect of NO as a vasodilator may play a role in its angiogenic effects.[27] Recently, Khan et al. tested the effect of VEGF165 treatment on rat dorsal skin flap viability and discovered gains in skin flap viability seen with VEGF165 were reversed with the addition of the non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NNA(15 mg/kg).[3] Therefore, it was concluded that local subcutaneous injection of VEGF165 in skin flaps is effective in augmentation of skin flap viability by an increase in NO production and an associated increase in blood flow. [3] In summary, these studies suggest that NO improves blood flow before and during the neovascularization process, and suggest that these mechanisms are underlying the improvements in flap survival area observed in the current study.

The results of this study extend previous concepts regarding the role of NO, and suggest that NO may also serve as a postoperative treatment of skin flaps to encourage skin flap survival and prevent distal necrosis. The present study successfully demonstrated the use of NO donors and electrical stimulation as a potential therapeutic treatment for the prevention of skin flap necrosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded via a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of biostatistician Alejandro Munoz-del-Rio and medical editor Kelsey Anderson in the completion of this work.

This study was performed in accordance with the PHS Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Animal Welfare Act (7 U.S.C. et seq.); the animal use protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of University of Wisconsin and William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital.

References

- 1.Clugston PA. A rat transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap model: Effects of pharmacological manipulation. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giunta RE, Holzbach T, Taskov C, et al. AdVEGF165 gene transfer increases survival in overdimensioned skin flaps. The Journal of Gene Medicine. 2005;7:297–306. doi: 10.1002/jgm.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan A, Ashrafpour H, Huang N, et al. Acute local subcutaneous VEGF165 injection for augmentation of skin flap viability: efficacy and mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1219–1229. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00143.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohmann R, Yowell R, Barton S, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone protects muscle flap microcirculatory hemodynamics from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Trauma. 1997;42:74–80. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuntscher MV, Kastell T, Engel H, et al. Late remote ischemic preconditioning in rat muscle and adipocutaneous flap models. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51:84–90. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000054186.10681.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mounsey R, Pang CY, Forrest C. Preconditioning: a new technique for improved muscle flap survival. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:549–52. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zahir K, Shamsuddin AS, Zink JR, et al. Ischemic preconditioning improves the survival of skin and myocutaneous flaps in a rat model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:140–50. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199807000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang WZ, Anderson G, Firrell JC, et al. Ischemic preconditioning versus intermittent reperfusion to improve blood flow to a vascular isolated skeletal muscle flap of rats. J Trauma. 1998;45:953–959. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199811000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang WZ, Anderson G, Guo SZ, et al. Initiation of microvascular protection by nitric oxide in late preconditioning. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2000;16:621–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuntscher MV, Kastell T, Altman J, et al. Acute remote ischemic preconditioning II: The role of nitric oxide. Microsurgery. 2002;22:227–231. doi: 10.1002/micr.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Um S, Suzuki S, Shinya T, et al. Involvement of nitric oxide in survival of random pattern skin flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:785–792. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199803000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordeiro PG, Santamaria E, Hu Q-Y. Use of a nitric oxide precursor to protect pig myocutaneous flaps from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2040–2048. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199811000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dale R, John VL, Roberto Iontophoresis for eyelid anesthesia. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21:845–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass J, Stephen RL, Jacobson SC. The quantity and distribution of radiolabeled dexamethasone delivered to tissue by iontophoresis. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:519–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1980.tb00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asai S, Fukuta K, Torri S. Topical adiministration of prostaglandin E1 with iontophoresis for skin flap viability. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:514–7. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heppenstall R. Constant direct current treatment for established nonunion of the tibia. Clin Orthop. 1983;178:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konikoff J. Electrical promotion of soft tissue repairs. Ann Biomed Eng. 1976;4:423–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02363553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su C, Im M, Hoopes JE. Tissue glucose and lactate following vascular occlusion in island skin flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70:202. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Im M, Lee W, Hoopes J. Effect of electrical stimulation on survival of skin flaps in pigs. Phys Ther. 1990;70:37–40. doi: 10.1093/ptj/70.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFarlane R, DeYoung G, Henry RA. The design of a pedicle flap in the rat to study necrosis and prevention. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965;35:177–82. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196502000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feelisch M. The use of nitric oxide donors in pharmacological studies. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1998;358:113–122. doi: 10.1007/pl00005231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papapetropoulos A, Garcia-Cardena G, Madri JA, et al. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3131–3139. doi: 10.1172/JCI119868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dulak J, Jozkowicz A, Chilian WM, et al. Nitric oxide in vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis and signaling response. Circulation. 2001;104:48e–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.9.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziche M, Morbidelli L, Choudhuri R, et al. Nitric oxide synthase lies downstream from vascular endothelial growth factor-induced but not basic fibroblast growth factor-induced angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2625–2634. doi: 10.1172/JCI119451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziche M, Parenti A, Ledda F, et al. Nitric axide oromotes proliferation and plasminogen activator production by coronary venular endothelium through endogenus bFGF. Circ Res. 1997;80:845–852. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, et al. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2567–2578. doi: 10.1172/JCI1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudlicka O, Brown MD, Silgram H. Inhibition of capillary growth in chronically stimulated rat muscles by NG-Nitro--Arginine, nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Microvascular Research. 2000;59:45–51. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1999.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]