Abstract

Background

Deficits in the transfer of information between inpatient and outpatient physicians are common and pose a patient safety risk. This is particularly the case for vulnerable populations such as patients with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis. These patients have unique and complex health care needs that may not be effectively communicated on standard discharge summaries, which may result in potential medical errors and adverse events.

Objective

To evaluate Canadian dialysis center directors’ perceptions of deficiencies in the content and quality of hospital discharge summaries for dialysis patients.

Methods

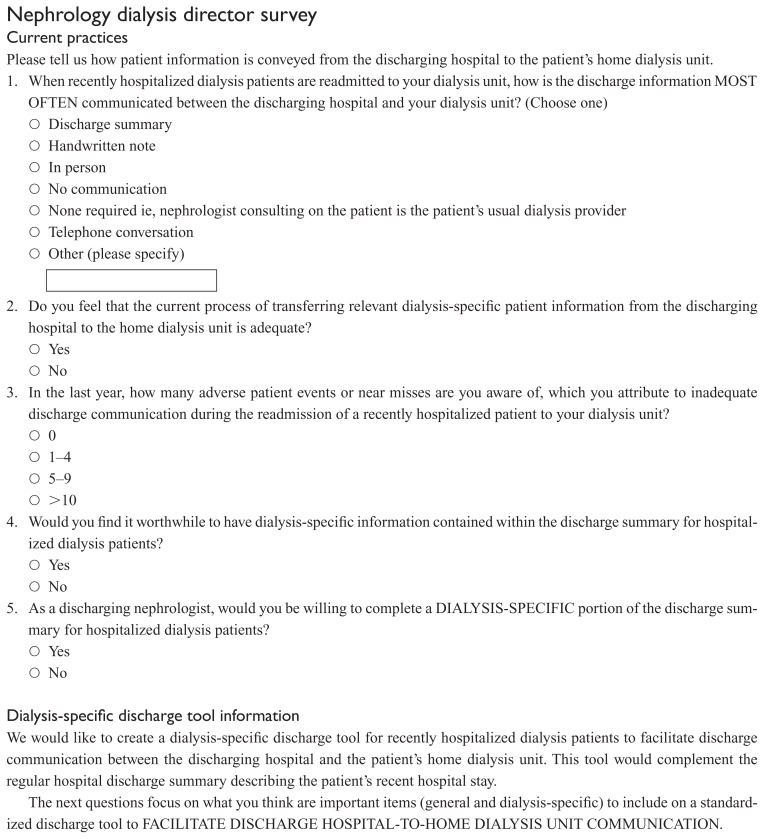

A web-based, cross-sectional survey of Canadian dialysis center directors was performed between September and November 2010. The survey consisted of three parts. The first part was designed to assess dialysis center directors’ attitudes on the quality of discharge summaries they receive. The second part was designed to elicit respondents’ preferences for discharge summary content, and the third part consisted of questions regarding demographic and practice information.

Results

Of 79 dialysis center directors, 21 (27%) completed the survey. Sixty-two percent felt that current discharge summaries inadequately communicate dialysis-specific information. Receipt of antibiotics for line sepsis or peritonitis, modifications to vascular access, and changes in target weight/dialysis prescription were rated as essential dialysis-specific information to include in discharge summaries by respondents.

Conclusion

Over three quarters of dialysis center directors find the current practice of transferring discharge information for hospitalized dialysis patients grossly inadequate. The inclusion of dialysis-specific information may improve the quality of discharge summaries for dialysis patients.

Keywords: information transfer, dialysis patients, discharge information

Background

Continuity of care is the process by which patients experience linked care from one health care setting to another. It has been defined as having three components: (1) physician continuity, (2) information continuity, and (3) management continuity. 1 Previous studies have consistently demonstrated deficiencies in each of these components across health care settings.2,3 This discontinuity in patient care has been associated with greater utilization of emergency services, increased hospitalization, higher mortality, and poor patient satisfaction.4,5

Although physician and management continuity is often difficult to attain after a patient is discharged from hospital, the timely transfer of information between hospital- based consultants and community-based physicians need not be. Historically, the hospital discharge summary has been the tool of choice for the communication of information after hospitalization. This simple intervention has helped to reduce adverse events after discharge, lower health care costs, and promote positive outcomes for patients.6,7 Still, there are often deficiencies in its content and accuracy which may adversely affect patient care.

While all patients are at risk when discontinuity of care occurs, those with more complex disease may be at an elevated risk of adverse events after hospital discharge.8 This makes the process of transmission of information to post-discharge health care providers of great importance. In an attempt to standardize the transmission of complete and relevant hospitalization information, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations in the USA established standards outlining the components that each hospital discharge summary should contain.9 Although this has led to improved communication and a reduction in adverse events after discharge, the “one size fits all” approach to discharge summary creation may be problematic and incomplete for the more fragile and vulnerable health care populations.10 One such population is those with end-stage renal disease on dialysis.

Patients on dialysis may be at increased risk for adverse events during transitions of care as they possess many of the characteristics associated with continuity of care gaps. They are often elderly, possess multiple medical comorbidities, are on multiple medications, and may have cognitive impairment.11,12 They also have unique dialysis-related issues that are complex and require specialized knowledge. Moreover, they may have their dialysis at centers different from the hospital to which they were admitted. Due to such issues, discharge summaries that contain only the standard components mandated by the Joint Commission will be deficient in important content relating to dialysis care which may have occurred during hospitalization. Such content may include changes in dialysis prescription, vascular access issues, receipt of blood transfusion which may sensitize patients and limit their transplantability, and receipt of intravenous iron. Collectively, these deficiencies may create an environment that can compromise patient safety and ultimately result in adverse events including rehospitalization and even death.

Given the complex care needs of dialysis patients, a specialized discharge summary, incorporating the components mandated by the Joint Commission and dialysis-specific information, would be helpful. This summary should be comprehensive, yet reader friendly and transmitted in a timely manner to the home dialysis unit of the patient upon their discharge from the hospital.

This study aimed to assess Canadian dialysis center directors’ opinions regarding the deficiencies in content and quality of currently used hospital discharge summaries for dialysis patients.

Methods

Study population and setting

A web-based, cross-sectional survey of Canadian nephrologists (excluding Quebec) from academic and nonacademic institutions was performed between September and November 2010. The sample frame was practicing nephrologists who were dialysis unit directors as determined by the Canadian Organ Replacement Registry (CORR) 2009 directory.13 We chose to focus on nephrologists who were dialysis unit directors primarily for feasibility reasons as the CORR directory was the only publically available resource listing nephrologists in Canada. In total, 75 academic and nonacademic nephrologists were eligible for participation in this survey. We chose only to focus on nephrologists as most discharge summaries in use already contain information relevant to the general practitioner but may be lacking information that is specific to those providing dialysis to patients with end-stage renal disease.

Survey design

The survey consisted of three parts. The first part included questions designed to assess attitudes on the quality of discharge summaries received for dialysis patients and the consequences of poor discharge communication between facilities. The second part of the survey was designed to elicit preferences for discharge summary content. We assessed preferences for discharge summary content by asking respondents to rank items using a three-point scale from 1, “always need to know,” to 3, “never need to know.” The third part of the survey consisted of questions regarding demographic and practice information. Descriptions of the questionnaire items and associated response categories for these research tools are included in the Appendix.

To ensure face and content validity, our questionnaire was developed using a focus group of experts consisting of four active nephrologists (three academic and one community) and one general internist with expertise in patient safety and continuity of care. The initial survey was reviewed and revised with the assistance of an additional nephrologist. This methodology has been used in previous survey studies across multiple disciplines.10,14

Although we did not formally pilot the study instrument, we did send a preliminary copy to two nephrologists for their input on the format and ease of completion of the survey.

Survey process

We posted the survey using an online survey program15 that allowed the respondent to answer the survey and send us the responses by email. The link to this online survey along with a cover letter was emailed to Canadian nephrologists who were also dialysis unit directors, using the CORR 2009 directory. A reminder survey was sent to nonrespondents one month after the initial survey via email. Participation was voluntary, and responses were anonymous. No identifying data were collected, and all results were analyzed in aggregate. Incomplete surveys were excluded. The survey and study were approved by the St Michael’s Hospital Ethics Board.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze survey responses. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, whereas ordinal and categorical variables were summarized using percentages and frequencies.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 79 eligible nephrologists who were emailed, 22 responded (28%). One nephrologist failed to complete the entire survey and was excluded. The majority of nephrologists worked in academic institutions (62%) and had graduated from medical school prior to 2000 (71%).

Discharge summary communication and content

Most nephrologists indicated that discharge information about their dialysis patients is most often communicated by discharge summary (38%). Handwritten notes were the next most frequent form of providing discharge information (28%). Five percent of nephrologists indicated that a majority of the time, discharge communication is not provided to them. A majority of respondents (62%) felt that the current process of transferring relevant dialysis-specific patient information from the discharging hospital to the home dialysis unit was inadequate. Seventy-six percent of participants indicated that they were aware of at least one adverse event or near miss occurring in their patients, which they could attribute to inadequate discharge communication.

Eighty-one percent of nephrologists felt it was worthwhile to include dialysis-specific information in discharge summaries. A similar percentage of nephrologists were willing to participate in the completion of such information on a discharge summary.

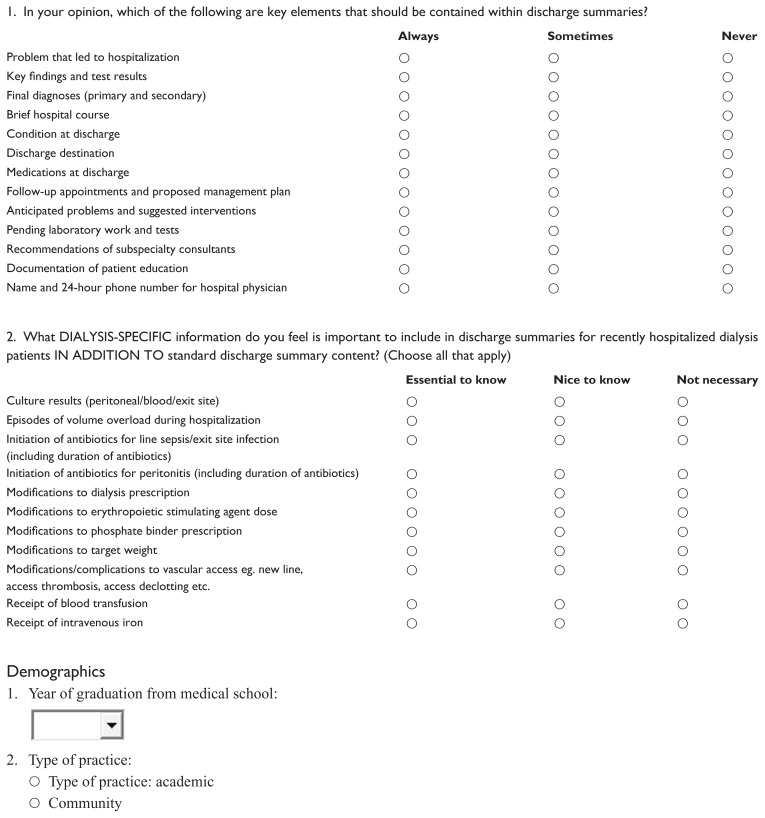

Preferences for discharge summary content

The rating for importance of discharge summary elements is shown in Table 2. Presenting problem, final diagnosis, medications at time of discharge and follow-up were the most important elements rated by the study participants.

Table 2.

Nephrologist perceptions of information that should be included on discharge summaries

| Discharge summary element | Always, n (%) | Sometimes, n (%) | Never, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem that led to hospitalization | 20 (95) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Key findings and test results | 16 (76) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) |

| Final diagnoses (primary and secondary) | 21 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Brief hospital course | 9 (43) | 11 (52) | 1 (5) |

| Condition at discharge | 13 (62) | 7 (33) | 1 (5) |

| Discharge destination | 12 (57) | 9 (43) | 0 (0) |

| Medications at discharge | 21 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Follow-up appointments and proposed management plan | 20 (95) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Anticipated problems and suggested interventions | 7 (33) | 13 (62) | 1 (5) |

| Pending laboratory work and tests | 10 (48) | 11 (52) | 0 (0) |

| Recommendations of subspecialty consultants | 11 (52) | 8 (38) | 2 (10) |

| Documentation of patient education | 0 (0) | 19 (91) | 2 (10) |

| Name and 24-hour telephone number for hospital physician | 5 (24) | 9 (43) | 7 (33) |

Among dialysis-specific discharge content, 95% of nephrologists specified that receipt of antibiotics for line sepsis or peritonitis was essential to include on discharge summaries. Similarly, a majority of nephrologists felt that modifications to vascular access, changes in target weight and changes in dialysis prescription were also essential to include (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nephrologist perceptions of important dialysis-specific information that should be contained within discharge summaries

| Dialysis-specific information | Essential, n (%) | Nice to know, n (%) | Unnecessary, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modifications to dialysis prescription | 17 (81) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) |

| Modifications to target weight | 16 (76) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) |

| Modifications to erythropoietic stimulating agent dose | 14 (66) | 6 (29) | 1 (5) |

| Modifications to phosphate binder prescription | 12 (57) | 8 (38) | 1 (5) |

| Modifications/Complications to vascular access, eg, new line, access thrombosis, access declotting, etc. | 18 (86) | 8 = 3 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Receipt of blood transfusion | 7 (33) | 13 (62) | 1 (5) |

| Receipt of intravenous iron | 4 (19) | 13 (62) | 4 (19) |

| Episodes of volume overload during hospitalization | 4 (19) | 12 (57) | 5 (24) |

| Initiation of antibiotics for peritonitis (including duration of antibiotics) | 20 (95) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Initiation of antibiotics for line sepsis/exit-site infection (including duration of antibiotics) | 20 (95) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Culture results (peritoneal/blood/exit site) | 14 (67) | 6 (29) | 1 (5) |

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to assess nephrologists’ perceptions and attitudes regarding continuity of care of dialysis patients post-hospitalization. Our findings indicate that many nephrologists are dissatisfied with the current transfer of discharge information on their patients and can attribute adverse events or near misses to this. Most nephrologists believed it was important for discharge summaries to contain dialysis-specific information and were willing to participate in the completion of such information. Dialysis-specific information that respondents felt was salient for discharge summaries to contain included: information related to infections associated with dialysis, modifications to vascular access, and changes to the dialysis prescription and target weight of the patient.

Traditionally, the discharge summary has been the main tool used to disseminate information about a patient’s diagnostic findings, hospital management, and arrangements for post-discharge follow-up. A recent systematic review by Kripalani et al16 demonstrated that a majority of discharge summaries are of relatively low quality as they often fail to convey sufficient information to the receiving physician. Critics of Kripalani et al’s16 findings have noted that they included studies that were primarily conducted prior to the creation of performance standards for discharge summary content by the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.9 They assert that Kripalani et al’s16 findings may therefore not reflect current practices. However, recent work has continued to demonstrate that despite standardization, important discharge information is still insufficiently communicated, particularly for specialized patient populations.14,17–19 Our study echoes this sentiment as 62% of surveyed nephrologists believed that important information is regularly omitted from the discharge summaries they receive. This trend may be explained by the fact that certain patient populations possess specialized medical issues that are unlikely to be addressed in a “one size fits all” discharge summary format.10 It may also reflect a paradigm change in the model of medical care whereby the family physician and not the specialist is the medical gatekeeper; thereby most correspondence is targeted to them.20 As such, the content of discharge that may be of significance to specialists may be omitted in order for the sake of brevity and clarity.

The change in the medical model, with its central focus on the family physician, may also impact on the receipt of the discharge summary. In our study, nephrologists did not receive any discharge correspondence for their patients almost 20% of the time. Perhaps nephrologists were overlooked by those drafting the discharge summary, as the summary authors did not want to circumvent the autonomy of the family physician as the leader of the health care team. A more compelling reason might be the relative difficulty of identifying a most-responsible nephrologist by patients who undergo chronic dialysis in units that employ a rotating nephrologist model of care where a different nephrologist rotates through the unit on a weekly basis. Moreover, practice patterns among nephrologists may have differed.

Many studies covering the items and format of a high-quality discharge summary have been published following a survey of the opinions of the physicians who receive them. Uniformly, most receiving physicians prefer a structured summary about two pages in length with content that includes the diagnoses, discharge medications, results of procedures, follow-up needs, and pending test results.16,21–25 Our survey results corroborate this; however, not all nephrologists found it necessary to always include pending tests. This may reflect differences in practice patterns amongst nephrologists whereby some assume the role of a primary care provider and are interested in the totality of information on the hospitalization while others focus only on dialysis-related issues.

In most hospitals, dialysis patients are often admitted to non-nephrology wards with the nephrology service consulting. As changes to the dialysis prescription are undertaken exclusively by nephrologists, this may not be communicated with the admitting service, which may impact on inclusion of such information on the discharge summary. Furthermore, even if this information is communicated to the admitting service, it may be unfamiliar to the receiving physician and potentially deemed not important enough to include. As a consulting service, nephrology may not be involved in the creation of the discharge summary, and therefore would be unable to include important information for the patient’s nephrologist beyond that which is included by the physician writing the summary. As previously mentioned, most discharge summaries are geared to the family physician and therefore may omit potentially important information for the nephrologist. The majority of nephrologists surveyed felt that it was necessary for the discharge summary to highlight the following dialysis-specific information: initiation (and duration) of antibiotics for line sepsis or peritonitis, modifications to vascular access, and modifications to the dialysis prescription and target weight (Table 3). Initiation (and duration) of antibiotics for line sepsis, peritonitis, or exit-site infections would likely be included in standard discharge summaries as such information is familiar to a broad set of health care professionals aside from nephrologists. In contrast, information concerning changes to the dialysis prescription and target weight are less likely to be communicated in the discharge summary.

Several study limitations must be addressed. Despite our best attempt, only 22 nephrologists responded to our survey yielding a relatively small sample size. However, our response rate is similar to other studies surveying physicians on their perceptions of the quality of discharge summaries they receive.14,23 This ensured that those nephrologists with a true interest in the subject were considered, but it is unclear whether their views were similar to nonresponders. Our study elicited responses from a pool of nephrologists across Canada, which may have biased the results as there may be regional variability in discharge practices influencing nephrologists’ opinions. That being said, our national sample and inclusion of both academic and nonacademic nephrologists increased the generalizability of our findings.

Our study results have several implications. Firstly, we have demonstrated what information nephrologists feel needs to be conveyed on the discharge summary for chronic dialysis patients. This information can be used in the development of a discharge summary tool in which items specifically adapted to dialysis patients can be added when these patients are hospitalized. Ultimately, such a modification will lead to improved discharge summary quality for dialysis patients which may lead to less medical errors and improved quality of care. Secondly, we have found that a majority of nephrologists are willing to collaborate in the process of discharge summary creation. Such an approach should aid in the accuracy of information contained within the discharge summary but may come at the expense of its timely transmission. This would be the case if the nephrologist was unable to complete the appropriate section of the discharge summary by a certain time, possibly due to a lack of awareness of the discharge date of the patient or a heavy workload. Finally, our study results raise awareness among hospital physicians as to the importance of the continuity of care of chronic dialysis patients after discharge.

Discharge summaries for specialized populations, such as patients on dialysis, present difficult choices. Not only do they have to convey information that is pertinent to the family physician in a concise and timely manner, but they also have to ensure that the content is of value to other physicians involved in the care of the discharged patient. We have demonstrated that a majority of nephrologists find the current practice of transferring discharge information for hospitalized dialysis patients grossly inadequate, which may lead to medical errors and lapses in care. Further research is needed to develop a discharge summary template for dialysis patients as a first step to improve the quality of transmitted discharge information.

Table 1.

Nephrologist perceptions of discharge information transfer and quality

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| How is discharge information most often conveyed between the discharging hospital and your dialysis unit? | |

| Discharge summary | 8 (38) |

| Handwritten note | 6 (28) |

| In person | 3 (14) |

| No communication | 1(5) |

| None required | 1(5) |

| Telephone conversation | 1(5) |

| Is the current process of transferring discharge information adequate? | |

| Yes | 8 (38) |

| No | 13 (62) |

| In the past year, how many adverse events or near misses can you attribute to inadequate transfer of discharge information? | |

| 0 | 5 (24) |

| 1–4 | 13 (62) |

| 5–9 | 2 (9) |

| >10 | 1 (5) |

| Would it be worthwhile to have dialysis-specific information contained within discharge summaries? | |

| Yes | 17 (81) |

| No | 4 (19) |

| Would you be willing to participate in the creation of a dialysis-specific portion of the discharge summary for hospitalized dialysis patients? | |

| Yes | 19 (91) |

| No | 2 (9) |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the nephrologists who participated in this study. Funding for this study was provided by grants from the Canadian Patient Safety Institute and St Michael’s Hospital. Ziv Harel has received a Master’s award from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Chaim Bell is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Canadian Patient Safety Institute chair in Patient Safety and Continuity of Care. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Appendix

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work other than the funding outlined in the Acknowledgments.

References

- 1.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–1221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA. 2005;293(5):565–571. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiell AP, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, van WC. Maintaining continuity of care: a look at the quality of communication between Ontario emergency departments and community physicians. CJEM. 2005;7(3):155–161. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500013191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forster AJ, Rose NG, van WC, Stiell I. Adverse events following an emergency department visit. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):17–22. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halasyamani L, Kripalani S, Coleman E, et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients – development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354–360. doi: 10.1002/jhm.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Standard http://www.jointcommission.org.

- 10.Kergoat MJ, Latour J, Julien I, et al. A discharge summary adapted to the frail elderly to ensure transfer of relevant information from the hospital to community settings: a model. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seliger SL, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Fink JC. Chronic kidney disease adversely influences patient safety. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(12):2414–2419. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapin E, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Seliger SL, Walker LD, Fink JC. Adverse safety events in chronic kidney disease: the frequency of “multiple hits”. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(1):95–101. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06210909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Directory of Participating Dialysis Centres, Transplant Centres and Organ Procurement Organizations in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2009. [Accessed January 13, 2012]. Available from: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/products/corr_directory_2009_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, Liss DT, Baker DW. Outpatient physicians’ satisfaction with discharge summaries and perceived need for an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(5):317–320. doi: 10.1002/jhm.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SurveyMonkey® [website on the Internet] Palo Alto, CA: Survey Monkey. com, LLC; 1999–2011. [Accessed January 13, 2012]. Available from: http://www.surveymonkey.com. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satzinger W, Courte-Wienecke S, Wenng S, Herkert B. Bridging the information gap between hospitals and home care services: experience with a patient admission and discharge form. J Nurs Manag. 2005;13(3):257–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2005.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Walraven C, Seth R, Laupacis A. Dissemination of discharge summaries. Not reaching follow-up physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:737–742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, et al. Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):219–225. doi: 10.1002/jhm.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watt WD. The family physician: gatekeeper to the health-care system. Can Fam Physician. 1987;33:1101–1104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster DS, Paterson C, Fairfield G. Evaluation of immediate discharge documents – room for improvement? Scott Med J. 2002;47(4):77–79. doi: 10.1177/003693300204700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Walraven C, Weinberg AL. Quality assessment of a discharge summary system. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1437–1442. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Walraven C, Duke SM, Weinberg AL, Wells PS. Standardized or narrative discharge summaries. Which do family physicians prefer? Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:62–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson S, Ruscoe W, Chapman M, Miller R. General practitioner-hospital communications: a review of discharge summaries. J Qual Clin Pract. 2001;21(4):104–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1762.2001.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maslove DM, Leiter RE, Griesman J, et al. Electronic versus dictated hospital discharge summaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):995–1001. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]