Abstract

Background

Patient-centered care has been proposed as a strategy for improving treatment outcomes in the management of psoriasis and other chronic diseases. A more detailed understanding of patients’ utilities and disutilities associated with treatment features may facilitate shared decision-making in the clinical encounter. The purpose of this study was to examine the features of psoriasis treatment that are most and least preferred by patients and to identify correlates of these preferences.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of 163 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis was conducted in a German academic medical center. We assessed patients’ characteristics, elicited their preferences for a range of potential treatment features, and quantified preference scores (utilities) associated with each treatment feature using hierarchical Bayes estimation. After identifying the most and least preferred treatment features, we explored correlates of these preferences using multivariate regression models.

Results

Mean preference scores (MPS) for the least preferred treatment features were consistently greater than those for the most preferred treatment features. Patients generally expressed strong preferences against prolonged treatments in the inpatient setting (MPS = −13.48) and those with a lower probability of benefit (MPS = −12.28), while treatments with a high probability of benefit (MPS = 10.51) were generally preferred. Younger patients and women were more concerned with treatment benefit as compared with older patients and men.

Conclusion

Both negative and positive preferences appear important for shared decision-making. Recognition of characteristics associated with strong negative preferences may be particularly useful in promoting patient-centered environments.

Keywords: conjoint analysis, patient preferences, treatment preferences, psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common skin disease with substantial impact on those afflicted.1,2 The disease burden and social stigma associated with psoriasis significantly affect physical and psychological well-being.1–3 Because there is no cure for psoriasis, disease management aims at reducing disease severity and improving overall health-related quality of life.4,5

Several forms of effective treatment have been developed for management of psoriasis.4,6 However, despite the availability of a wide range of options, treatment nonadherence is high.7 Shared decision-making, a central component of patient-centered care, is a strategy that promotes involvement of patients in the management of their disease, in part to enhance adherence.8 Shared decision-making may involve eliciting patients’ preferences and the active use of preferences in treatment decision-making.8,9 As a result, a more detailed understanding by physicians of the treatment preferences of patients with psoriasis within the framework of shared decision-making has been advocated.10

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with psoriasis have distinct preferences for many aspects of the treatment process,11 including treatment location, mode of delivery,12 probability of treatment benefit,13 and frequency. 14 Much of this work has focused almost exclusively on positive preferences or the utility of a given treatment choice. However, this approach tends to ignore the rationality of decision-making in which individuals weigh possible gains against the possible losses (or the disutility) associated with a given choice.15

To promote shared decision-making in the management of psoriasis, it may be useful to characterize better patients’ preferences for treatment features they desire and those they wish to avoid. Further, identifying factors associated with patient utilities and disutilities may inform the development of more effective treatment strategies. The aim of this study was to examine features of psoriasis treatment that are most and least preferred by patients and to identify correlates of these preferences.

Methods

Recruitment

Patients were recruited from the outpatient psoriasis clinics in the Department of Dermatology, University Medical Centre Mannheim, Heidelberg University. Selection was based on criteria that ensured participants could potentially be offered a wide range of currently available psoriasis treatments. Specifically, patients were eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years of age, had physician-diagnosed psoriasis that was moderate or severe according to the criteria of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use16 (ie, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index >10 and/or had involvement of the head, and palmar and plantar surfaces), or had psoriatic arthritis with skin involvement according to Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis criteria.17 Patients with psoriatic arthritis, but no skin involvement, and those unable to complete an online survey independently were excluded. Informed consent was obtained prior to study participation. The study followed the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University.

Data collection and data elements

Patients completed a self-administered online survey before their medical appointment. The survey involved assessment of patient preferences for psoriasis treatment using a choice-based conjoint analysis exercise.18 Patients’ characteristics and other potential confounders of patients’ preferences were also assessed by the online survey and included gender, age in years, marital status (single, couples living together, divorced, widowed), employment status (employed/unemployed), highest level of educational attainment based on categories used by the German Federal Statistics Office (≤11 years of schooling = low, 12–15 years = medium, >15 years = high),8 net monthly household income (< 1500, 1500–3000, > 3000), disease duration in years,19–21 smoking status (still smoking, previous smoker, never smoked),21 current therapies (topical, light, tablets, injection, infusion) and known comorbidities associated with psoriasis (psoriatic arthritis, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression).20,22,23

The conjoint analysis exercise has been described in detail elsewhere.12,24 In summary, it involves five main stages: identifying treatment attributes for the study; determining levels (categories) for each attribute; presenting hypothetical scenarios consisting of different attribute levels; obtaining participant preferences for each scenario; and data analysis.18,25 In specifying the treatment attributes for psoriasis, we first identified a range of potentially appropriate and available treatment options by reviewing the German Evidence-based Guidelines for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Consultations with dermatologists confirmed and, in some cases, augmented our selection. We then decomposed the treatment list into attributes and attribute levels. Four attribute levels for each treatment attribute were specified to limit respondent burden (see Table 1).12

Table 1.

Profile of treatment attributes and attribute levels used in conjoint analysis exercises

| Treatment attributes | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration | 5 minutes | 15 to 30 minutes | 1 hour | 2 hours |

| Treatment frequency | Once every 3 months | Once every 2 weeks | Two times each week | Twice daily |

| Treatment cost | €0 per month | €50 per month | €100 per month | €200 per month |

| Treatment location | At home | At home and follow-up at local doctor’s | Outpatient clinic | Hospital for 3 weeks |

| Treatment delivery method | Topical | Tablets | Injection/intravenous infusion | Light therapy |

| Magnitude of beneficial effects | 100% reduction | 75% reduction | 50% reduction | 25% reduction |

| Duration of beneficial effects | 1 year or more | 6–8 months | 3–5 months | 2 weeks |

| Probability of side effects | 100% | 50% | 10% | 1% |

| Probability of beneficial effects | 100% | 80% | 60% | 40% |

| Reversibility of side effects | 100% | 80% | 60% | 40% |

| Side effects severity | Temporary, minor discomfort on skin | Constant, moderate discomfort on skin | Temporary, moderate side effects more than skin | Severe side effects more than skin |

Survey design

A survey containing items related to the conjoint analysis was designed for online administration using Sawtooth software (Sawtooth Inc, Sequim, WA). The survey comprised two parts to enable distinctions between patient preferences for treatment processes (eg, location of treatment) and those for possible treatment outcomes or consequences (eg, possibility of side effects). Patients were presented with 12 pair-wise comparisons of randomly selected hypothetical treatment scenarios (for an example, see Schaarschmidt et al12).

Data analysis

Conventionally, latent class analysis is used for segmentation of conjoint analysis samples into subgroups of respondents for each treatment attribute, resulting in relative importance scores for each attribute.26 However, because we were specifically interested in looking at the most and least preferred levels within each treatment attribute, and not relative attribute importance, individual-level preference (utility) scores for treatment attribute levels were estimated using hierarchical Bayes estimation.18 Mean preference scores for each attribute level were calculated using data from the entire sample and were rank-ordered from most to least preferred. Independent associations of patient characteristics and other potential correlates of patients’ preferences with the preference scores for the most preferred and least preferred psoriasis treatment attribute levels (as dependent variables) were evaluated using six separate multivariate linear regression models. Three models were developed for the most preferred attribute levels (ie, those with the highest utility scores) and three models for the three least preferred attribute levels. Statistical analyses were performed using either Sawtooth software or SPSS (v 19; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). We used an alpha value of 0.05 to indicate statistical significance. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, we did not adjust the alpha value for the multiple testing implicit in the models we generated.

Results

Of the 163 participants recruited, 67 (41.1%) were women, and the mean age was 49.3 (range 18–80) years. The mean number of years since diagnosis (ie, disease duration) was 18 (range 1–75) years. Participants who reported that they were working represented 58.9% of the study sample (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristics | (n = 163) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Women | 67 (41.1%) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD (range) | 49.3 ± 14.1 (18–80) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 38 (23.3%) |

| Couple | 99 (60.7%) |

| Divorced, widowed, separated | 26 (16.0%) |

| Education | |

| ≤11 years | 29 (17.8%) |

| 12–15 years | 97 (59.5%) |

| >15 years | 37 (22.7%) |

| Monthly household income (in euros) | |

| < €1500 | 55 (33.7%) |

| €1500–3000 | 73 (44.8%) |

| >€3000 | 35 (21.5%) |

| Employment status | |

| Working | 96 (58.9%) |

| Not working | 67 (41.1%) |

| Disease duration (years), mean ± SD (range) | 18.0 ± 13.9 (1–75) |

| Currently receiving psoriasis therapy | 153 (93.9%) |

| Current therapy | |

| Topical | 61 (37.4%) |

| Light | 24 (14.7%) |

| Tablets | 46 (28.2%) |

| Injection | 28 (17.2%) |

| Infusion | 8 (4.9%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 44 (27.0%) |

| Diabetes | 13 (8.0%) |

| Cardiovascular | 23 (13.5%) |

| Depression | 21 (12.9%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Still smoking | 61 (37.4%) |

| Smoked before | 59 (36.2%) |

| Never smoked | 43 (26.4%) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Mean preferences for attribte levels

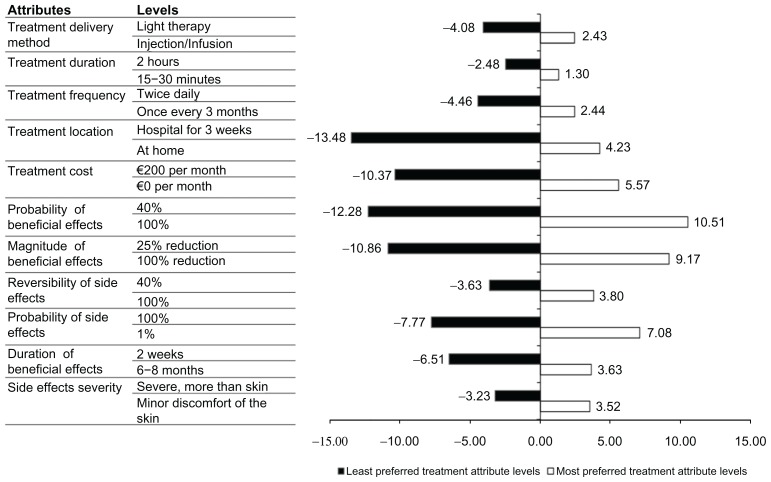

Utility scores for the most and least preferred attribute levels are shown in Figure 1. The greater the importance of the attribute levels to the patients, the higher the mean utility score. A positive sign (+) indicates positive utility and a negative sign (−) indicates a converse relationship, or disutility.

Figure 1.

Mean preference scores of the most and least preferred attribute levels.

In nearly every instance, the magnitude of the mean preference score for the least preferred attribute level exceeded that for its most preferred level. The lowest rank-ordered attribute levels, ie, those that were least preferred, included hospital stay for 3 weeks (−13.48), lower (40%) probability of benefit (−12.28), and lower (25%) expected magnitude of benefit (−10.86). Patients expressed a strongly negative preference for a treatment in which side effects were highly likely (−7.77) compared with treatments for which side effects may be severe (−3.23). Conversely, patients expressed strong positive preferences for a treatment with the highest (100%) probability of benefit (+10.51), followed by the possibility of achieving significant reduction of psoriasis plaques (+9.17). Other relatively strongly positive preferences were expressed for treatments with a lower probability of side effects (+7.08), no costs (+5.57), and treatments that could be administered at home (+4.23).

Correlates of patient preferences for most and least preferred attribute levels

We observed correlates between patient or treatment characteristics and six of the treatment attribute levels for which patients expressed the strongest positive and negative preferences (see Table 3). For example, younger patients and women were more concerned with treatment benefit than men and older patients. Singles, divorced, widowed, and subjects separated from their partners preferred treatments with a high probability of benefit and treatments expected to have a high magnitude of benefit, and least preferred treatments with a lower magni tude of beneficial effects, as compared with those who were married or living with a partner. Treatment at the hospital for 3 weeks appeared to be less preferred by singles as compared with couples (ie, those married or living with a partner) and by patients with higher educational attainment (more than 15 years of schooling) as compared with those with lower educational attainment (≤11 years of schooling).

Table 3.

Multiple regression analyses examining correlates of most and least preferred treatment attribute levels

| Correlates | Most preferred attribute levels | Least preferred attribute levels | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Gender (referent, men) | ||||||||||||

| Women | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.096 | 0.270 | 0.013 | 0.892 | 0.013 | 0.887 | 0.011 | 0.043 | −0.190 | 0.029 |

| Age, years | −0.134 | 0.021 | 0.112 | 0.259 | 0.157 | 0.044 | 0.051 | 0.624 | −0.225 | 0.030 | −0.035 | 0.047 |

| Marital status (referent, couple) | ||||||||||||

| Single | 0.066 | 0.523 | 0.066 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.917 | 0.167 | 0.015 | −0.018 | 0.862 | 0.071 | 0.018 |

| Divorce, widowed, separated | 0.107 | 0.025 | 0.141 | 0.010 | 0.041 | 0.664 | −0.063 | 0.495 | 0.035 | 0.699 | 0.104 | 0.028 |

| Education (referent, ≤11 years) | ||||||||||||

| 12–15 years | −0.043 | 0.011 | 0.150 | 0.088 | −0.085 | 0.374 | −0.068 | 0.463 | 0.054 | 0.556 | −0.147 | 0.094 |

| >15 years | −0.020 | 0.835 | −0.131 | 0.144 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.060 | 0.022 | 0.019 | 0.839 | 0.177 | 0.860 |

| Monthly household income (referent, <€1500) | ||||||||||||

| €1500–3000 | −0.004 | 0.970 | −0.004 | 0.967 | −0.107 | 0.290 | 0.158 | 0.110 | −0.018 | 0.853 | 0.035 | 0.707 |

| >€3000 | −0.044 | 0.647 | 0.198 | 0.031 | −0.066 | 0.507 | 0.044 | 0.050 | 0.016 | 0.862 | −0.169 | 0.064 |

| Current therapy (referent, other therapy) | ||||||||||||

| Topical | 0.060 | 0.019 | −0.121 | 0.157 | 0.093 | 0.315 | 0.105 | 0.029 | −0.078 | 0.381 | 0.108 | 0.205 |

| Light | −0.092 | 0.296 | 0.049 | 0.550 | 0.138 | 0.025 | −0.071 | 0.417 | −0.025 | 0.771 | −0.153 | 0.041 |

| Tablets | 0.069 | 0.432 | −0.175 | 0.035 | −0.082 | 0.363 | −0.200 | 0.022 | 0.015 | 0.862 | 0.181 | 0.030 |

| Injection | 0.068 | 0.048 | 0.024 | 0.793 | −0.092 | 0.350 | 0.015 | 0.870 | 0.158 | 0.049 | −0.003 | 0.983 |

| Comorbidities (referent, other comorbidity) | ||||||||||||

| Psoriatic arthritis | 0.004 | 0.078 | −0.044 | 0.215 | 0.022 | 0.062 | 0.009 | 0.940 | −0.031 | 0.270 | −0.043 | 0.061 |

| Diabetes | −0.003 | 0.971 | −0.060 | 0.481 | −0.042 | 0.630 | 0.007 | 0.992 | 0.005 | 0.958 | −0.022 | 0.794 |

| Cardiovascular | 0.087 | 0.361 | −0.042 | 0.641 | 0.046 | 0.636 | −0.078 | 0.409 | −0.150 | 0.110 | 0.051 | 0.567 |

| Depression | −0.016 | 0.855 | −0.183 | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.630 | 0.136 | 0.112 | 0.008 | 0.925 | 0.131 | 0.107 |

| Smoking status (referent, still smoking) | ||||||||||||

| Smoked before | −0.137 | 0.006 | −0.205 | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.744 | 0.143 | 0.161 | 0.171 | 0.070 | 0.174 | 0.062 |

| Never smoked | −0.120 | 0.024 | −0.225 | 0.017 | 0.114 | 0.260 | 0.048 | 0.621 | 0.137 | 0.182 | 0.240 | 0.054 |

Notes: Model 1, high (100%) probability of beneficial effects from treatment; model 2, high (100%) magnitude of beneficial effects from treatment; model 3, lower (1%) probability of side effects from treatment; model 4, treatment in hospital for 3 weeks; model 5, lower (40%) probability of beneficial effects from treatment; model 6, lower (25%) magnitude of beneficial effects from treatment; the bold text shows alpha values < 0.05.

A low probability of side effects was most preferred by older patients as compared with younger patients, by patients with more than 15 years of schooling as compared with those with ≤11 years of schooling, and by patients receiving light therapy as compared with those receiving other therapies. Patients with lower educational attainment (≤11 years of schooling) appeared to be most concerned about treatment benefits. Patients receiving injections or topical treatments appeared to prefer treatment with a high probability of benefit. However, patients receiving injections least preferred treatments expected to have a lower probability of benefit, while those receiving topical treatments least preferred treatment at the hospital for 3 weeks. The results also showed that depressed patients were less concerned with the expected magnitude of beneficial effects. Patients still smoking appeared to be more concerned with the probability of benefit and the reduction in psoriasis plaques as compared with those who were not current smokers (ie, those who had smoked before and quit or who had never smoked).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to expand on the patient preference literature for individuals with psoriasis by examining preferences for levels within psoriasis treatment attributes. We demonstrated not only the utility of receiving a preferred treatment, but also the disutility associated with receiving a nonpreferred treatment. Moreover, we identified several correlates of patient preferences for treatment attributes that were most and least preferred.

We observed that the magnitude of the mean preference scores for least preferred attribute levels was consistently higher than the magnitude of the mean scores for the most preferred attribute levels. Our results suggest that patients are not only concerned about receiving preferred treatments, but perhaps are more concerned that treatments associated with strong disutility not be recommended.27 Evidence from the psychology literature reveals a negativity bias, specifically that many are affected to a greater extent by bad things happening to them rather than good events. As a result, individuals may be more motivated to avoid bad things than to pursue good things.15 Moreover, previous work suggests that the saliency of bad events or negative emotions lasts longer than good events or positive emotions.28,29 Taken together, these prior findings may explain the magnitude of the negative utility that participants in our study assigned to the least preferred treatment attribute levels. Based on our results, it is possible that failure to acknowledge negative preferences in treatment decision-making, ie, recommending treatments associated with strong disutility, may affect patient satisfaction and adherence with recommended treatment to a greater degree than recommendation of treatments with attributes that are only weakly preferred.

For example, the strongly negative utilities identified through the conjoint analysis in our study suggest that participants were more concerned about improvement of their skin condition than about the reversibility or the severity of treatment side effects. Studies exploring the significance of treatment side effects and treatment benefit in chronic disease management have reported mixed results.11 In some studies, patients valued the risk and the severity of treatment side effects over treatment benefit,11,30 while in others patients were reported to be willing to accept the risks of treatment if benefits were perceived to be high.12,31 These contradictory findings may have resulted from the way in which the severity of side effects was explicitly defined or presented (eg, “risk of liver damage or skin cancer” versus “side effects involving more than the skin”). In cases where the severity of side effects was defined, treatment side effects became the most important determinant of patient treatment preferences.11 When eliciting patient preferences, explicitly defining treatment attributes has both advantages and disadvantages. For example, use of explicit language (eg, “risk of liver damage or skin cancer”) may result in dominant preferences in which respondents become unwilling to trade between attributes.32 However, using explicit language has the advantage of being more realistic and makes the choice task less abstract.32 Therefore, patients’ preferences, may be influenced not only by the processes of care (eg, treatment frequency) or benefits (eg, side effects), but also by the way the information is presented to patients.33

Further, our findings showed that sociodemographic, treatment, and behavioral aspects of individual patients appear to be important in determining patient preferences for treatment attributes. In multivariate analysis, we found that younger patients and women preferred treatments with greater likelihood of benefit, while older patients appeared more concerned with treatment side effects. A study by Gelfand et al reported that younger patients and women with psoriasis had greater impairment in quality of life as compared with men and older patients, potentially explaining why younger patients and women prefer treatments with greater likelihood of benefit.34 We also found that patients with higher educational attainment least preferred prolonged inpatient treatment, possibly because greater education correlates with acquiring a position with higher earning potential, greater responsibility,35 and therefore busier schedules that would limit the ability to devote blocks of time to treatment.

Findings from previous studies have shown that smoking is significantly associated with increased psoriasis severity, and heavy and long-term smokers are more likely to have severe psoriasis,36,37 potentially explaining why patients still smoking in our sample appeared to be more concerned with the probability of treatment benefit and reduction in psoriasis plaques. The correlations we observed between patient characteristics, treatment history, behavioral factors, and their treatment preferences (Table 3) raise the possibility that patient “profiles” or patient preference subgroups may exist. Acknowledging these profiles, if present, may be useful as clinicians develop treatment recommendations to optimize adherence.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine patients’ treatment preferences in terms of features they most and least prefer. However, there are studies that have examined preferences for treatment attributes. Similar to a study reporting that time to achieve moderate improvement was rated higher than time to relapse,13 our results suggest strong patient preferences for treatment with high (100%) probability of benefit as compared with a long (6–8-month) duration of benefit (or time to relapse). These findings may indicate that patients are more concerned with the onset than the duration of treatment benefit. Further, in our previous study, location of treatment was the most important treatment attribute.12 From our current results, we may interpret this prior finding as arising from patients’ strong disutility for inpatient treatment associated with hospital stays of 3 weeks. Strong preferences for the location of treatment, in particular, suggest that patients are concerned and have opinions about the experience of treatment beyond its ultimate outcomes. This conclusion is also supported by other studies that have used conjoint analysis in the health care setting to assess the value of process versus outcomes of treatments.12,38

The findings presented here justify further research. When examining patient preferences, future preference elicitation studies should consider both preferences for most and least preferred treatment options or attributes. A focus solely on aspects of treatment that a patient prefers may provide incomplete information on forces that influence treatment choice and adherence.

Strengths and limitations

We used choice-based conjoint analysis to measure patient preferences for psoriasis treatment attributes, a method considered to represent best the way people make everyday choices and which is easy to use and efficient in assessing patient preferences.18 Moreover, the hierarchical Bayes method we used to estimate individual-level preference scores is said to improve the reliability and predictive validity of individual preference models because the method borrows information from other respondents in the sample to stabilize estimates for each individual.26

However, it is important to note that, in preference elicitation, simplifications are made to make the exercises feasible. In conjoint analysis we assume, for example, that the utility functions attributable to respondents are additive and preferences for attribute levels are independent. However, preferences for attribute levels may not be independent in all cases.18 Further, although it is a strength of our study that we accounted for individual characteristics in our multivariable models, there might be individual differences even within these subgroups that are not captured by the rather broad categories we used. Therefore, treatment recommendations may need to be individualized to an even greater extent than suggested by our reference to patient profiles or preference subgroups. It may also be considered a limitation of this study that treatment attributes and attribute levels were specified without input from the patients. However, during the pilot phase of the study, feedback from the patients was used to refine and improve the comprehensiveness and clarity of the identified features of psoriasis treatment. Finally, our study sample included only patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, and the treatments they were offered may have differed from those offered to patients with mild psoriasis. Therefore, the generalizability of the study sample is limited.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis have preferences about the treatments they receive that are both strongly negative and strongly positive. To improve the effectiveness of psoriasis treatment, physicians deciding on which treatment to recommend should not only heed the best available evidence, but may also want to consider explicitly the utility and disutility patients attach to processes and outcomes of treatment for psoriasis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Litaker (Departments of Medicine, Epidemiology, and Biostatistics, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) for his valuable suggestions in revising the manuscript; Wiebke K Peitsch, Astrid Schmieder, Marthe-Lisa Schaarschmidt (Department of Dermatology, University Medical Centre, Mannheim) for their support in conducting the study; Anette Oberst (Department of Dermatology, University Medical Centre Mannheim) for help with study documentation; and the doctors and nursing staff of the Department of Dermatology at the University Medical Centre, Mannheim, for support with patient recruitment.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life – results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation Patient Membership Survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(3):280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustin M, Kruger K, Radtke MA, Schwippl I, Reich K. Disease severity, quality of life and health care in plaque-type psoriasis: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Germany. Dermatology. 2008;216(4):366–372. doi: 10.1159/000119415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitt J, Meurer M, Klon M, Frick KD. Assessment of health state utilities of controlled and uncontrolled psoriasis and atopic eczema: a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(2):351–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Housman TS, Mellen BG, Rapp SR, Fleischer AB, Jr, Feldman SR. Patients with psoriasis prefer solution and foam vehicles: a quantitative assessment of vehicle preference. Cutis. 2002;70(6):327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nast A, Boehncke WH, Mrowietz U, et al. S3-guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris update 2011. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9(Suppl 2):S1–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0379.2011.07680.x. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards HL, Fortune DG, O’Sullivan TM, Main CJ, Griffiths CEM. Patients with psoriasis and their compliance with medication. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):581–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson S, Strub P, Buist S, et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):566–577. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0907OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(12):600–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecluse LL, Tutein Nolthenius JL, Bos JD, Spuls PI. Patient preferences and satisfaction with systemic therapies for psoriasis: an area to be explored. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(6):1340–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashcroft DM, Seston E, Griffiths CEM. Trade-offs between the benefits and risks of drug treatment for psoriasis: a discrete choice experiment with UK dermatologists. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(6):1236–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaarschmidt ML, Schmieder A, Umar N, et al. Patient preferences for psoriasis treatments: process characteristics can outweigh outcome attributes. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(11):1285–1294. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seston EM, Ashcroft DM, Griffiths CEM. Balancing the benefits and risks of drug treatment – a stated-preference, discrete choice experiment with patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1175–1179. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, Murphy J, Ibbotson SH, Ferguson J. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(5):973–978. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumeister RF, Bratlavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Rev Gen Psychol. 2001;5(4):323–370. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claes C, Kulp W, Greiner W, von der Schulenburg JM, Werfel T. Therapy of moderate and severe psoriasis. GMS Health Technol Assess. 2006;2 Doc07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2665–2673. doi: 10.1002/art.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(5):1–180. doi: 10.3310/hta5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friends-of-Europe. Just what the doctor ordered: An EU response to medication non-adherence. Brussels: 2010. [Accessed January 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.friendsofeurope.org/Contentnavigation/Events/Eventsoverview/tabid/1187/EventType/EventView/EventId/841/EventDateID/845/PageID/5043/JustwhatthedoctororderedAnEUresponsetomedicationnonadherence.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reich K, Mrowietz U. Treatment goals in psoriasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5(7):566–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06343.x. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salzburg Global Seminar. The greatest untapped resources in health care? Information and involving patients in decisions about their medical care. 2010. [Accessed January 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.salzburgglobal.org/current/Sessions.cfm?IDSPECIAL_EVENT=2754.

- 22.Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Nast A, Reich K. Strategies for improving the quality of care in psoriasis with the use of treatment goals – a report on an implementation meeting. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(Suppl 3):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine – reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2189–2194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr077003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmieder A, Schaarschmidt ML, Umar N, et al. Comorbidities significantly impact patients’ preferences for psoriasis treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.08.023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1530–1533. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orme BK. Getting Started With Conjoint Analysis Strategies for Product Design and Pricing Research. 1st ed. Madison, WI: Research Publishers LLC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz A, Goldberg J, Hazen G. Prospect theory, reference points, and health decisions. Judgm Decis Mak. 2008;3(2):174–180. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldon KM, Ryan R, Reis HT. What makes for a good day? Competence and autonomy in the day and in the person. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1996;22(12):1270–1279. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas DL, Diener E. Memory accuracy in the recall of emotions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(2):291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraenkel L, Bogardus S, Concato J, Felson D. Unwillingness of rheumatoid arthritis patients to risk adverse effects. Rheumatology. 2002;41(3):253–261. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry D, Bradlow A, Bersellini E. Perceptions of the risks and benefits of medicines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other painful musculoskeletal conditions. Rheumatology. 2004;43(7):901–905. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Bekker-Grob EW, Hol L, Donkers B, et al. Labeled versus unlabeled discrete choice experiments in health economics: an application to colorectal cancer screening. Value Health. 2010;13(2):315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gamliel E, Peer E. Attribute framing affects the perceived fairness of health care allocation principles. Judgm Decis Mak. 2010;5(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelfand JM, Feldman SR, Stern RS, Thomas J, Rolstad T, Margolis DJ. Determinants of quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a study from the US population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(5):704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blaug M. The correlation between education and earnings: what does it signify? Higher Educ. 1971;1:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Leffondre K, et al. Relationship between smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(12):1580–1584. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attwa E, Swelam E. Relationship between smoking-induced oxidative stress and the clinical severity of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2011;25(7):782–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seston EM, Elliott RA, Noyce PR, Payne K. Women’s preferences for the provision of emergency hormonal contraception services. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29(3):183–189. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]