Abstract

Background

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is considered uncommon in black populations including those of Sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of this review was to determine the pattern of presentation of AMD in our hospital located in Ibadan, the largest city in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

A retrospective review of all cases with AMD presenting to the Eye and Retinal Clinic of the University College Hospital, Ibadan, West Africa was undertaken between October 2007 and September 2010.

Results

In the 3 years reviewed, 768 retinal cases were seen in the hospital, 101 (14%) of which were diagnosed with AMD. The peak age was 60–79 years. The male to female ratio was approximately 2:3. More males presented with the advanced form of dry AMD than females (odds ratio = 2.33). However, more females had advanced wet AMD than males (odds ratio = 1.85). Wet AMD was seen in 40 cases (40%).

Conclusion

The review determined that, as AMD is not uncommon and wet AMD is relatively more common in our hospital than has been reported previously, this is probably true of Ibadan in general.

Keywords: age-related maculopathy, choroidal neovascular membrane, retinal, vitreoretinal, drusen

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of visual impairment among elderly white people in the developed world.1 The disease was initially thought to be uncommon in people with dark skin living in developing countries,2 but recent studies have shown that it is more prevalent in developing countries such as India3 and Nigeria4 than previously thought. AMD has also been shown to be an important cause of poor vision in the western5–7 and southeastern8,9 parts of Nigeria. Adequate data are lacking concerning the prevalence of the disease in developing countries. The reason for this is connected to the paucity of trained vitreoretinal surgeons and equipment necessary to make accurate diagnoses of this important cause of poor vision and blindness in the elderly population. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the number of older people is currently increasing due to increased survival rates from improved health facilities; hence, the increased number of persons being diagnosed with the disease. The recent explosion in published research about this disease suggest its increasing prevalence.

In 2006, we published on our experiences with retinal diseases in our institution and the need to establish a vitreoretinal center in the subregion.7 The International Council of Ophthalmology, International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, and a representative from Carl Zeiss, Inc, visited our institution and helped initiate sponsored fellowship training in subspecialties including vitreoretinal. Furthermore, equipment for subspecialties was purchased or donated by the sponsors. The patient load has increased, meaning that residents (junior postgraduate doctors) now have more cases to learn from. The retina subspecialty is fully established.

This review aims to determine if AMD is a problem in our hospital, a teaching and tertiary public hospital located in Ibadan, the largest city in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

All retinal cases seen in the retina clinic between December 2007 and December 2010 were reviewed after subspecialization (prior to 2007, ophthalmologists at our hospital were nonspecialized; now there are seven subspecialties: retina, cornea and anterior segment, glaucoma, orbit and plastic, pediatric ophthalmology, neuro-ophthalmology, and community ophthalmology). A retina register of all cases seen during the period was reviewed. All case notes of patients with the diagnosis of AMD were retrieved and included in the study.

Criteria for diagnosis

With the aid of slit lamp biomicroscopy using the 78D lens and fundus photography, the detection of soft drusen of <65 μm with pigmentary changes in the macula indicated early age-related maculopathy (ARM). The presence of drusen between 65 and 125 μm (size of vein at the disc margin), one large druse (125 μm), or multiple large drusen without the advanced forms indicated intermediate ARM. Choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) is suggested by any of the following findings: macular scar, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) detachment, subretinal blood, or exudates not accounted for by any other disease apart from ARM. CNVM indicated an advanced wet ARM, also known as wet AMD. Geographic atrophy is a well-demarcated area of macular RPE atrophy of at least 175 μm in diameter. This suggests an advanced form of dry ARM, also known as dry AMD10 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Staging of age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

| Stage of AMD | Findings |

|---|---|

| Early ARM | Soft drusen of <65 μm with pigmentary changes in the macula |

| Intermediate ARM | Drusen sized from 65 to 125 μm (size of vein at the disc margin), presence of one large druse (125 μm), or multiple large drusen without the advanced forms |

| Late dry ARM | Geographic atrophy (a well-demarcated area of macular RPE atrophy at least 175 μm in diameter) |

| Late wet ARM | Choroidal neovascular membrane, macular scar, RPE detachment, subretinal blood or exudates not accounted for by any other disease apart from ARM |

Abbreviations: ARM, age-related maculopathy; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Results

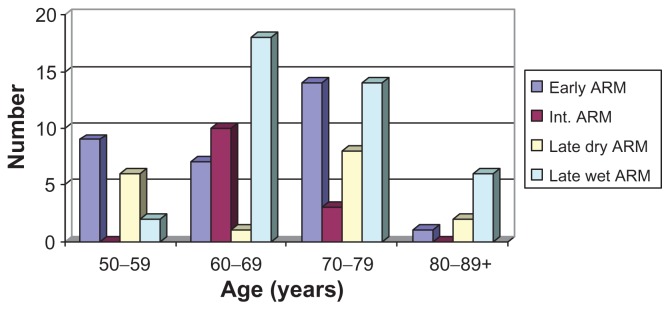

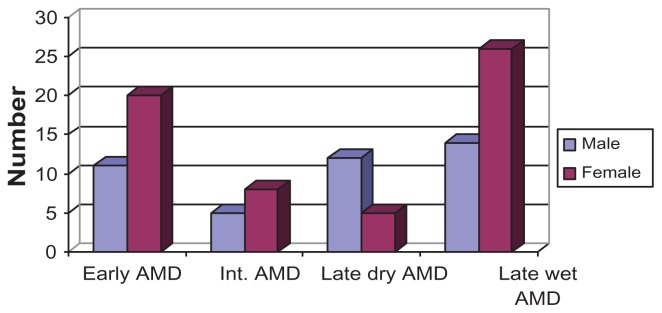

In the 3 years under review, 768 retinal cases were seen in the hospital, of which 101 (14%) were diagnosed with AMD. The peak age was 60–79 years. Patients aged 60–69 and 70–79 years old constituted two-thirds of the cases (Table 2, Figure 1). Early ARM had a steady rise while there was more intermediate ARM in the 60–69-years-old age group. Late wet ARM occurred mainly in the 60–69 and 70–79 age groups. Late dry ARM showed two peaks, in ages 50–59 and 70–79 years. The 70–79 year age group showed a significant proportion of patients with early and late forms of both types of AMD. Wet AMD was seen in 40 cases (40%). The male to female ratio was about 2:3. More males presented with the advanced form of dry AMD than females (odds ratio = 2.33). However, more females had advanced wet AMD than males (odds ratio = 1.85; see Table 3 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Age distribution for AMD in Ibadan

| Stage/age (years) | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early ARM | 9 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 31 (31) |

| Intermediate ARM | – | 10 | 3 | – | 13 (12.5) |

| Late dry AMD | 6 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 17 (16.5) |

| Late wet AMD | 2 | 18 | 14 | 6 | 40 (40) |

| Total (%) | 17 (16.5) | 36 (36) | 39 (39) | 9 (8.5) | 101 (100) |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; ARM, age-related maculopathy.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of age-related macular degeneration in Ibadan.

Abbreviation: ARM, age-related maculopathy.

Table 3.

Sex distribution of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in Ibadan

| Sex/Diagnosis | Male | Female | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early AMD | 11 | 20 | 31 (31) |

| Intermediate AMD | 5 | 8 | 13 (12.5) |

| Late dry AMD | 12 | 5 | 17 (16.5) |

| Late wet AMD | 14 | 26 | 40 (40) |

| Total (%) | 42 (41.5) | 59 (58.5) | 101 (100) |

Figure 2.

Sex distribution of AMD in Ibadan.

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; int., intermediate.

Discussion

AMD is not uncommon and contributes to a significant proportion of ophthalmic presentation in Ibadan, Sub-Saharan Africa. This is contrary to previous reports that have suggested AMD is uncommon in people of African descent.11–17

The peak age of presentation in this study is similar to that in developed countries.1 The sex distribution is also similar to previous studies, with a slight female preponderance.1,12,13 More females presented with early AMD and the late form of wet AMD, while more males had advanced dry AMD.

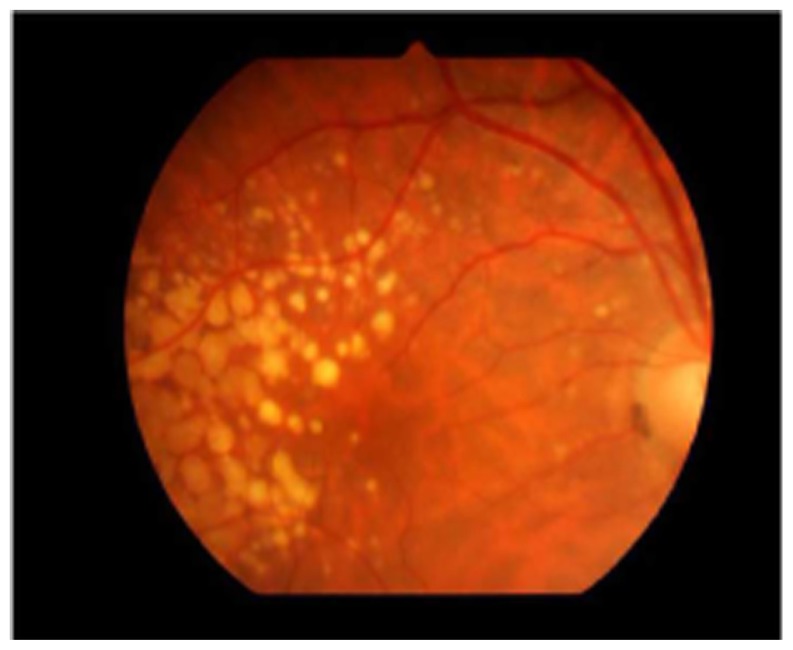

CNVM from AMD was found in about 40% of AMD cases, as opposed to previous reports that have shown rates between 10% and 20%;7,14,15 this might be related to better examination and diagnostic procedures following subspecialization. Dry AMD was still responsible for more of the presentations when we consider the early form. Intermediate AMD with large drusen occurred in a significant proportion (Figure 3); hence, the need to educate patients about the benefit of the vitamin supplements suggested by the Age-Related Eye Disease Study.16 This review has shown that most patients presented with the advanced stage of the disease (Figure 4). With an increasing number of elderly people being diagnosed, provision of vision services is therefore imperative.

Figure 3.

Large drusen in intermediate AMD.

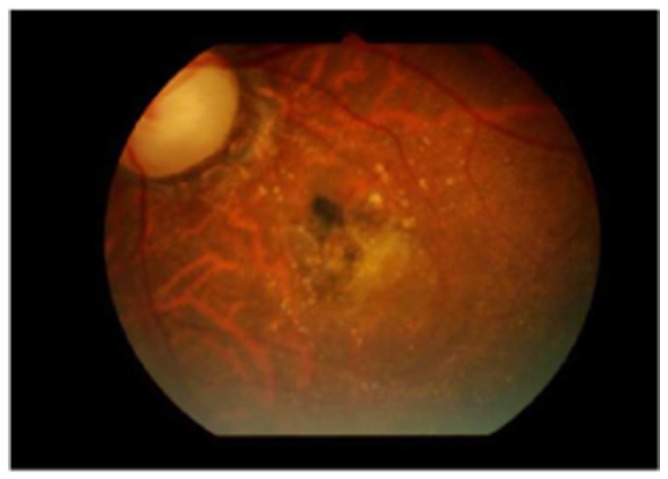

Figure 4.

Partly scarred choroidal neovascular membrane.

Six patients (two males and four females, with an average age of 62 years) presented with breakthrough vitreous hemorrhage necessitating vitrectomy. They had severe hemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachments similar to the cases described for idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.18 Indocyanin green angiography is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, but this was not available in our center. Therefore, these patients were referred for further evaluation.

Limitations

Our center is relatively new, with few diagnostic tools. The presence of fundus fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography would increase the diagnostic yield for occult wet AMD. The study was hospital based, possibly producing a higher prevalence of the disease; hence, there is a need for a population-based survey.

Conclusion

AMD is a significant issue in Ibadan, Sub-Saharan Africa. The need for patients’ education and regular eye examinations for the elderly is advocated in Sub-Saharan Africa. A large population-based study is warranted to determine the true prevalence of the disease.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author declares no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, et al. Barbados Eye Studies Group. Nine-year incidence of age-related macular degeneration in the Barbados eye studies. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnaiah S, Das T, Nirmalan PK, et al. Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: findings from the Andhra Pradesh eye disease study in South India. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4442–4449. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nwosu SN. Prevalence and pattern of retinal diseases at the Guinness Eye Hospital, Onitsha, Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7(1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adegbehingbe BO, Majengbasan TO. Ocular health status of rural dwellers in south-western Nigeria. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15(4):269–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fafowora OF. Prevalence of blindness in a rural ophthalmically under-served Nigerian community. West Afr J Med. 1996;15(4):228–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oluleye TS, Ajaiyeoba AI. Retinal diseases in Ibadan. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(12):1461–1463. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezepue UF. Magnitude and causes of blindness and low vision in Anambra State of Nigeria (results of 1992 point prevalence survey) Public Health. 1997;111(5):305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nwosu SN. Low vision in persons aged 50 and above in the onchocercal endemic communities of Anambra State, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2000;19(3):216–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bird AC, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, et al. International classification for ARM and AMD. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39(5):367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein R, Klein BE, Knudtson MD, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in 4 racial/ethnic groups in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein R, Rowland ML, Harris MI. Racial/ethnic differences in age-related maculopathy. Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ophthalmol. 1995;102(3):371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)31012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen SJ, Cheng CY, Peng KL, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of age-related macular degeneration in an elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: the Shihpai Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(7):3126–3133. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman DS, Katz J, Bressler NM, Rahmani B, Tielsch JM. Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration: the Baltimore Eye Survey. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(6):1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bressler SB, Muñoz B, Solomon SD, West SK Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Study Team. Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Project. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(2):241–245. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD. Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration: Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. JAMA. 1994;272(18):1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, et al. Racial differences in the cause specific prevalence of blindness in East Baltimore. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(20):1412–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111143252004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yannuzzi LA, Ciardella A, Spaide RF, Rabb M, Freund KB, Orlock DA. The expanding clinical spectrum of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(4):478–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150480005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]