Abstract

Force-generating contractile cells of the myocardium must achieve and maintain their primary function as an efficient mechanical pump over the life span of the organism. Because only half of the cardiomyocytes can be replaced during the entire human life span, the maintenance strategy elicited by cardiac cells relies on uninterrupted renewal of their components, including proteins whose specialized functions constitute this complex and sophisticated contractile apparatus. Thus cardiac proteins are continuously synthesized and degraded to ensure proteome homeostasis, also termed “proteostasis.” Once synthesized, proteins undergo additional folding, posttranslational modifications, and trafficking and/or become involved in protein-protein or protein-DNA interactions to exert their functions. This includes key transient interactions of cardiac proteins with molecular chaperones, which assist with quality control at multiple levels to prevent misfolding or to facilitate degradation. Importantly, cardiac proteome maintenance depends on the cellular environment and, in particular, the reduction-oxidation (REDOX) state, which is significantly different among cardiac organelles (e.g., mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum). Taking into account the high metabolic activity for oxygen consumption and ATP production by mitochondria, it is a challenge for cardiac cells to maintain the REDOX state while preventing either excessive oxidative or reductive stress. A perturbed REDOX environment can affect protein handling and conformation (e.g., disulfide bonds), disrupt key structure-function relationships, and trigger a pathogenic cascade of protein aggregation, decreased cell survival, and increased organ dysfunction. This review covers current knowledge regarding the general domain of REDOX state and protein folding, specifically in cardiomyocytes under normal-healthy conditions and during disease states associated with morbidity and mortality in humans.

Keywords: heart disease, reduction-oxidation state, cardiac proteome, chaperone, stress response, glutathione, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

this article is part of a collection on Protein Handling. Other articles appearing in this collection, as well as a full archive of all collections, can be found online at http://ajpheart.physiology.org/.

Introduction

With over 100,000 proteins, the mammalian proteome encompasses various sizes (3–1000 amino acids), shapes (α-helixes and β-sheets), functions (i.e., structural dynamic protein complex such as sarcomere, enzymes, receptors, ion channels, etc.), and neighborhoods [such distinct cellular compartments: nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and mitochondria] in a cell. Proteome homeostasis, termed “proteostasis,” is dynamically achieved by coordinating protein synthesis (gene expression), organization/folding (with the intervention of molecular chaperones and protein-protein interactions), and degradation [calpain, ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), and lysosome-dependent autophagy with molecular chaperone contribution] [see reviews on proteostasis (40), sarcomere maintenance (13), and degradation-UPS (74)]. Therefore, the loss of proteostasis is among the common but not widely appreciated features of pathophysiological stresses generated by distinct cardiovascular diseases leading to cardiac dysfunction.

Reduction-oxidation (REDOX) reactions are constantly handling electron transfer from one molecule to another. This drives the energy-ATP production during aerobic respiration and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) via the electron transport chain (ECT) in mitochondria. Electrons can prematurely escape and reduce molecular oxygen to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Table 1). When there is an excess of ROS production and a deficit in ROS scavenging mechanisms, cells experience deleterious oxidative stress (7). REDOX imbalance has direct effects on protein environment and proteostasis. Unfortunately, the concepts of “cellular REDOX state” or “REDOX environment” are often used without clear definitions leading to the most mistaken assumption that the REDOX state simply represents a global cellular characteristic (Table 1).

Table 1.

REDOX-related definitions

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Redox cycle | Two half reactions corresponding to oxidation (i.e., electron loss) and reduction (i.e., electron gain) for completion |

| Redox state | Ratio of the interconvertible oxidized and reduced form of a specific redox couple (e.g., NAD+/NADH) |

| Redox environment | Summation of the products in the reduction potential and reducing capacity of the linked redox couples as found in a biological fluid, organelle, cell, and tissue |

| Redox couple | A pair made of the interconvertible oxidized and reduced form |

| Some couples are just evaluated by the ratio oxidation/reduction form (NAD+/NADH; NADP+/NADPH) | |

| Other couples to be fully estimated required that their absolute concentration is known, e.g., GSSG/2 GSH, which could be used as an indicator for the redox environment | |

| With Cys/CySS and thioredoxins, those couples function as reductive counterparts to cellular oxidants, controlling redox state of oxidizable thiols in proteins | |

| This directly impacts protein structure and, therefore, function | |

| ROS | Superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical |

| RNS | Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite |

| Oxidative stress | Imbalance redox state with increased level of ROS and RNS |

| Reductive stress | Imbalance redox state with an increased levels of reducing equivalents in the form of redox couples (e.g., GSH/GSSG, NADPH/NADP, etc.) |

REDOX, reduction-oxidation; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrosative species.

Like other cell types, cardiomyocytes share basic features of proteostasis and REDOX state, but they are postmitotic, highly specialized, force-generating, and beating cells (13). In terms of proteostasis, there is permanent turnover of contractile proteins in an environment under pressure to maintain the REDOX equilibrium due to the high number of mitochondria, which produce the required ATP energy while generating potentially deleterious ROS (Table 1, and Fig. 1). In fact, heart failure accompanies significant imbalances in REDOX state (oxidative/reductive stress) and alterations of numerous proteins, which are causally linked to myocardium dysfunction. Major clinical trials to test the efficacy of antioxidant treatment targeting REDOX equilibrium in heart diseases have, so far, been disappointing. Said trials question whether these therapeutic approaches are ineffective in reaching the precise sites of actions, indiscriminately modify global REDOX parameters, or promote deleterious consequences in susceptible individuals (11).

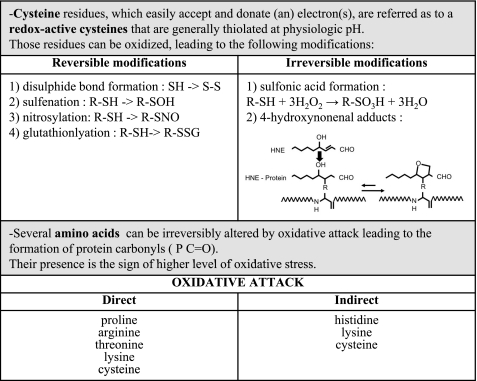

Fig. 1.

Main oxidative protein residue posttranslational modifications. Amino acids can be differently modified under oxidative environment. Those modifications can be reversible or not, induced directly or indirectly. Those posttranslational modifications are important as they affect protein structure and function.

To cover the vast topic of proteostasis and REDOX state, this review is divided into five subsections: 1) Primer on protein translation, folding and degradation in cardiomyocytes; 2) REDOX state: cellular and subcellular effects on proteostasis; 3) Cytosolic/ER stress response and Protein chaperone: critical intermediates between proteostasis and REDOX state; 4) Proteostasis, REDOX state, and cardiac diseases; and 5) Therapeutic agents: cardiac friends and foes in the fight.

Primer on Protein Translation, Folding, and Degradation in Cardiomyocytes

Heart tissue contains various types of cells (i.e., cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells) among which the contractile cells represent about 30–40% in number but 75% in cellular volume (including 35% volume occupied by mitochondria) (67, 98, 108). In contrast to other cell types found in organs such as skin or intestine, the adult cardiomyocytes have very limited regenerative capacity as the cell turnover rate was recently estimated between 0.4 and 1% per year in humans (9).

For organ integrity and maintenance, cardiac cells must rely on the renewal of the cellular components, in particular the proteins that represent on average 16% of the heart weight [reviewed in (41, 87)]. Protein synthesis and degradation are tightly coupled biological processes that maintain equilibrium conditions under normal contractile activity. However, when cardiac workload increases, the level of protein synthesis is significantly augmented such that phenotypic changes of cardiomyocytes lead to physiological or pathological cardiac hypertrophy, depending on the demands for higher contractile activity (see Cardiac hypertrophy). To investigate the molecular mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy, a classical method is the in vitro manipulation of isolated cardiomyocytes, whose size and the incorporation of leucine 3H can be measured as indexes of cardiac hypertrophy and protein synthesis, respectively. In response to various hypertrophic stimuli, cardiac size and protein synthesis were found to increase on average to the same extent. Conversely, reduced hemodynamic workload leads to cardiac atrophy as demonstrated in vivo by heterotropic isografts, which can maintain perfused hearts for prolonged periods of time (54). Reduced cardiac mass was shown to result from a significant decrease in protein synthesis [up to 50% in <2 wk, (53)], as well as from elevated activity of UPS (80). Such responses suggest the existence of mechanosensors in cardiomyocytes, which can link the intensity of contraction to the molecular pathway regulating protein synthesis and/or degradation. One example illustrating such possible mechanoproteostasis link is the muscle LIM protein, which is localized to the membrane and translocated to the nucleolus upon excessive contraction. This muscle LIM protein translocation is associated with a threefold increase in ribosomal S6 protein, which is likely to impact the level of protein synthesis (12).

More specifically, myosin and actin are particularly enriched in cardiomyocytes and form, in association with numerous other critical proteins, the cardiac contractile apparatus, organized in a structural-functional subunit, termed the “sarcomere” (13). The protein turnover rates from protein synthesis to degradation have been extensively evaluated for the cardiac contractile proteins. For example, the basal half-life can be as long as 15 days for myosin (71) or much shorter, as in the case of troponin subunits (T1/2, 3–5 days). Thus there is a large variability of stability among proteins participating to the same contractile structure, and this can have important consequences for cardiac function under pathological conditions.

In all cells, cardiomyocytes in particular, a very delicate step between the translation from the messenger RNAs and the assembly of the amino acid chain into a functioning product corresponds to the appropriate folding and organization of the amino chain in three-dimensional structure. The historical paradigm has established a strong link among protein structure, function, and well-ordered conformation. Nevertheless, cumulative bioinformatics evidence indicates that 25 to 30% of eukaryotic proteins are mostly disordered, whereas 50% of the proteins are partially disordered (96). This implies even more dynamic requirements for proteins to reach their functional status. Completion of protein folding and functional organization are not entirely based on a spontaneous process but require transient association with molecular chaperones in which productive interactions are heavily influenced by errors and other properties in the primary sequence of the protein (genetic mutation, see http://cardiogenomics.med.harvard.edu/project-detail?project_id=230#data) and REDOX environment (see next paragraph). Misfolded proteins are typically targeted for degradation. Such molecular mechanisms underlie the inherited cardiomyopathies caused by mutations in sarcomeric or sarcomere-associated proteins, whose accumulation and aggregation have dramatic consequences on cardiac function.

Cardiac proteostasis is functionally related to the assembly of the sarcomere from the sarcomeric and myofibrillar proteins, which are synthesized, folded, and further assembled in multiprotein structures through a sequential complex process called sarcomerogenesis. The most mature myofibrils are found in the perinuclear region, whereas the Z-disc corresponds to a subcellular region where defined sarcomeric compounds are assembled (13). The addition of new sarcomeres to the structure is operated within an hour, indicating a highly dynamic process that depends tightly on proper protein conformation and interaction. Finally, sarcomeric addition can occur either in parallel (concentric hypertrophy) or in series (eccentric hypertrophy) in response to different external mechanical stressors (pressure or volume overload). Altogether, these observations illustrate the different levels of protein regulation from synthesis to assembly of multi-molecular structure as the sarcomeric apparatus.

In contrast to protein synthesis that operates through one single ribosomal machinery, three distinct and complementary modus operandi have been identified for destroying cellular components and organelles: namely, the calpain/calpastatin system, the UPS, and the organelle-dependent autophagy. Several reviews have recently addressed the role played by these three different but interconnected mechanisms of cardiac sarcomere proteolysis-degradation (72, 74, 75). While those proteolytic processes are functional and required in the normal heart, they become critical in stressed hearts and, therefore, can be the object of therapeutic manipulations (see Cardiotoxicity as a severe drawback for efficient cancer drugs).

Often neglected, there is a fourth temporal dimension that, under circadian control, affects both synthesis and protein degradation processes in the heart. Such coordinated activities occur during periods of low activity when heart rate and blood pressure are reduced, creating optimal conditions for sarcomere repair and regeneration (13).

REDOX State: Cellular and Subcellular Effects on Proteostasis

Living organisms are constantly exposed to changes in their environment (nutrients, temperature, day-night cycle, exposure to pathogens, toxicants, etc.), and diverse differentiated cells have to adjust themselves to these variable conditions to maintain REDOX homeostasis. The reader may consult the main definitions related to REDOX state in Table 1. Importantly, REDOX reactions do not reach thermodynamic equilibrium, but biological homeostasis requires a complex network of interacting REDOX couples regenerated by enzymatic pathways (33). Imbalances of cellular REDOX homeostasis can occur when the generation of ROS exceeds existing antioxidant capacity (oxidative stress) or, conversely, when antioxidant capacity exceeds ROS generation (reductive stress). It is a critical to maintain REDOX homeostasis since imbalanced REDOX causes severe damages.

The intracellular environment of cardiac cells is not a homogenous milieu, nor is the cardiac REDOX state (84). Table 2 depicts several features of the cellular compartmentalization, including the steady-state REDOX potentials of the major REDOX couples in organelles and cytoplasm (Table 2). Cardiomyocytes exhibit a defined organization of their cytoplasm, occupied mainly by the highly structured protein complex forming the sarcomeric-contractile apparatus. Cardiomyocytes also contain organelles forming subcellular compartments with common and specific proteomes (nucleus, mitochondria, ER, and lysosomes). Those compartments display different characteristics for proteostasis, REDOX state, and regulatory proteins including chaperones (33, 45, 47) (Table 2). Although the intracellular environment is mostly reductive, there are two oxidizing compartments in the cell: namely, the mitochondria intermembrane space and the ER. Despite existing qualitative assessments of the REDOX state in intracellular compartments, the more desirable quantitative determinations, especially of REDOX potential at subcellular levels, remain difficult, challenging, and a critical unfinished task for the entire field (30, 63) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Compartmentalized REDOX potential, proteins, and main chaperones

| Cytoplasm | Mitochondria | Endoplasmic Reticulum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-state redox potential of major REDOX couples | |||

| Eh GSSG | −280 mV | −300 mV | −150 mV |

| Eh CySS | −160 mV | ||

| Eh NADP | −393 mV | −415 mV | |

| Eh Trx1 | −280 mV (C)/−300 mV (N) | ||

| Eh Trx2 (mitochondria), mV | −360 mV | ||

| Thiol REDOX protein/enzymes | |||

| GSH synthesis | -Glutamyl-cysteine synthetase & glutamate cysteine ligase (GLC): + | ||

| -Glutaredoxin 1 (Grx1): + | -Glutaredoxin 2 (Grx2) (C, N): + | ||

| -Glutaredoxin 3 (Grx3): −/+ | |||

| -Glutaredoxin5 (Grx5): +++++ | |||

| -Nucleoredoxin(Nrx): −/+ | |||

| -Peroxiredoxin1 (Prx1): +++ | -Peroxiredoxin3 (Prx3): +++, c muscle | -Peroxiredoxin 4 | |

| -Peroxiredoxin1 (Prx2): ++++ | |||

| -Peroxiredoxin1 (Prx5): +++ | |||

| -Thioredoxin1 (Trx1): low in heart | -Thioredoxin 2 (Trx2): +++, c muscle | ||

| -Thioredoxin reductase 1: low in heart | -Thioredoxin reductase 2: low in heart | ||

| -Ero1 alpha: ± | |||

| -Ero1 beta: + | |||

| Chaperones (main) | |||

| Small Hsps (with crystallin domain) | -HspB1( Hsp25/27): +++, multiple tissues | ND | ND |

| -HspB2 (MKBP): +, c/sk muscle specific | |||

| -HspB3: +, c/sk muscle specific | |||

| -HspB5 (CryAB): ++++, c/sk muscle, lens, brain | |||

| -HspB6 (Hsp20): ++, c/sk muscle | |||

| -HspB7 (CvHsp): ++++++, c/sk muscle | |||

| -HspB8 (Hsp22, H11): ++, c/sk muscle | |||

| Hsp40 DNAJ | -DNAJA1: +++ | DNAJA3: down in DCM | -DNAJB9 (ERdj4): ++ |

| -DNAJB1: inducible | -DNAJB11 (ERdj3) | ||

| -DNAJB5: redox/cardiac hypertrophy | -DNAJC1 (ERdj1) | ||

| -DNAJC10 (ERdj5) | |||

| Hsp70 family | HspA8 (Hsc70): ++++ | HspA9 (Grp75): ++++ | HspA5 (Grp78): ++++ |

| HspA1B: +++, inducible | |||

| Hsp90 family | HspC1 (Hsp86): ++++ | HspC4 (Hsp90B1) | |

| HspC4 (Hsp84): ++++++++ | |||

| Chaperonin related | HspE (Hsp10) | ||

| HspD (Hsp60): ++++ | |||

The number of (+) indicates the level of expression in heart. DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; AF, atrial fibrillation; c/sk, cardiac/skeletal; ND, not detected.

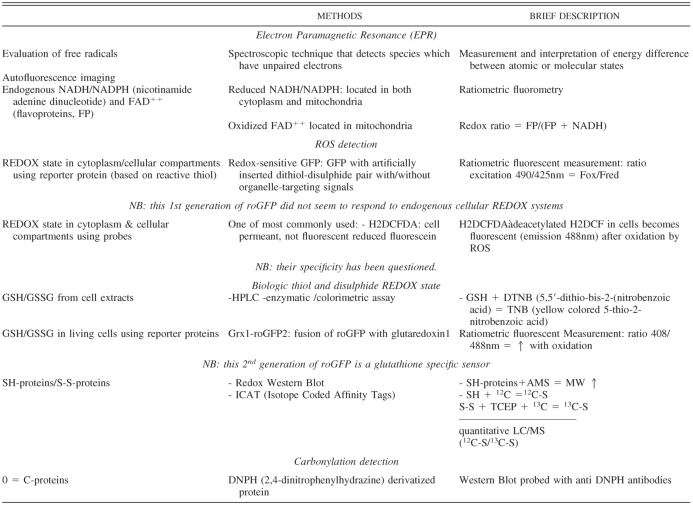

Table 3.

Methods for proteostasis and REDOX state evaluation

Mitochondria.

The heart has a constant need for energy, and 35% of the cardiomyocyte volume is occupied by mitochondria. Mitochondria produce ATP through OXPHOS along the ECT, which includes complex I and III as two main sites of ROS production. There are three subpopulations of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes, located either under the sarcoplasmic membrane [subsarcolemmal mitochondria (SS)] or between sarcomeres [intermyofibrillar mitochondria (IMF)] and around the nucleus (perinuclear mitochondria). Based on isolation techniques, two populations of mitochondria can be separated (non-IMF or SS and IMF) and shown to be morphologically and biochemically different (49, 82). Such fractions were shown to have different levels of activities for mitochondrial complexes of the ECT and to be differentially affected by oxidative posttranslational modifications of OXPHOS proteins (70). For example, protein carbonylation affects more severely SS mitochondrial proteins, whereas nitration is found higher in IMF organelles. ATP synthase subunits are among the most carbonylated proteins in both types of mitochondria. This can impact REDOX state as mitochondrial ECT dysfunction often leads to oxidative stress.

Such oxidative modification of proteins can impact other mitochondrial functions such as the control of apoptosis (49) or the cardiac Ca2+ signaling (25, 60). The IMF mitochondria are surrounded by a network of membranous compartments forming sarcoplasmic reticulum and are positioned close to microdomains of elevated local Ca2+. Evidence for physical coupling between the outer mitochondrial membrane and the sarcoplasmic reticulum has led to the speculation that a potential cross talk could also exist at a REDOX-state level between the two compartments (26).

These interactions remain to be further investigated, in particular to determine whether there is any further correlation between SS and IMF mitochondria with the mitochondrial specific REDOX couples and antioxidant enzymes: thioredoxin2/thioredoxin reductase 2, MnSOD, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate), which produces NADPH essential to maintain GSH/GSSG (Table 2).

Although endowed with its own genome and protein synthesis apparatus, mitochondria are dependent on the nuclear genome for synthesis of numerous nuclear-encoded proteins subsequently imported in the organelle. Similarly, mitochondria rely on the synthesized/recycled pool of GSH produced in the cytoplasm since they can only recycle it. GSH enters the organelle using carboxylate or oxoglutarate carriers (8, 59). This is another indication of interactions between cellular compartments, and despite its potential critical importance for REDOX balance of the mitochondria, this mechanism of import has surprisingly received little attention to date.

Endoplasmic reticulum.

In cardiac cells, the ER compartment exerts multiple functions related to protein folding and maturation of membrane-bound and secretory proteins, N-linked protein glycosylation, phospholipid, and steroid synthesis. It is also critically involved in Ca2+ dynamic storage with ryanodine receptor, releasing the ion in the cytoplasm while sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pumps it back into the ER compartment during each diastole (35). Cardiac ER is also organized in various domains with specific properties regarding Ca2+ handling (sublocalization of the Ca2+ channels) and interactions with mitochondria (25). Regarding protein folding, the ER compartment is a well-known, highly oxidizing environment (61). New proteins entering the ER compartment upon translation and translocation are constantly introducing reducing equivalents. To maintain such an oxidizing REDOX environment, ER contains specific protein such as ER oxidoreductin (ERO) and ERO1α and -β, the two isoforms existing in mammals. Those proteins function through an ERO-protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) pathway where reactive cysteines located on both proteins play an important role, regulating each other's activity (61). ERO1 activity can generate ROS, which can diffuse across the ER membrane, potentially leading to oxidative damages of ER intramembranous and/or cytoplasmic proteins. Because mouse models deficient in both ERO1 isoforms exhibited minor phenotype, it was suspected that this molecular machinery was working in parallel with some other REDOX proteins. Peroxiredoxin 4 was identified as one efficient candidate able to oxidize PDI (112). It is worth mentioning that none of these REDOX proteins is highly expressed in the heart (ERO1α and -β, PDI, and peroxiredoxin 4) in contrast to actively secreting cells. Nevertheless, peroxiredoxin 4 exhibits a defined profile of expression in the heart with a higher expression in the atria than in the ventricles and a higher expression in the right ventricle than in the left ventricle (atria > right ventricle > left ventricle).

There is a constant and complex communication between the more reduced cytoplasm and the highly oxidized ER. Reducing equivalents can enter the ER via transmembrane electron carriers [NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4), cytochrome B, and lipophilic vitamins] or through specific transporters which import GSH and other protein thiols. Oxidizing equivalents are also collected from the cytoplasm to ER lumen (e.g., FAD) (61).

Cytosolic/ER Stress Response and Protein Chaperone: Critical Intermediates Between Proteostasis and REDOX State

Since the heart has special energetic and protein regeneration-maintenance requirements, one could expect a high demand for molecular chaperones to secure cardiac proteostasis. Chaperones transiently bind with other proteins (clients) to assist their proper folding (or refolding) so that client proteins achieve their proper conformation and functional competency (8, 21, 32, 47, 102). Chaperones are found in the cytoplasm as well as in the different cellular compartments such as ER or mitochondria (Table 2).

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are the best-known chaperones, and their expression in the heart versus other tissues can be compared using available microarray data (BioGPS) (104) (Table 2). Several HSPs belonging to the different families, mainly organized based on their molecular weight, are more expressed in the heart than in other tissues (47). In particular, the small HSPs are well represented among abundant HSPs in the heart: HspB1 (Hsp25/27), HspB2 (myotonic dystrophy protein kinase-binding protein), HspB3, HspB5 (α-B-crystalline), HspB6, HspB7, and HspB8 [reviewed in (93, 99)]. Despite the tissue-specific enrichment of HspB1, HspB2, and HspB5 during development and in the adult heart, the single deficiency in HspB1 or the combined deficiency for HspB2 and HspB5 did not severely modify the cardiac phenotype in knockout mice (14, 44). This could be explained by a potential compensatory mechanism between the numerous small HSPs expressed in heart. While there is not yet any knockout line for the other members of the small HSPs family, multiple experiments demonstrate their importance in cardiac function under pathological stress [e.g., HspB6 (28) and small HSPs (26, 27, 50, 56)].

In addition to the physiological expression of chaperones, stress conditions can upregulate several of them as a defense mechanism (heat shock response and ER stress response) (64, 102) (Fig. 2). One of the stress conditions existing in cardiomyocytes corresponds to important changes in REDOX state, which impact protein conformation, leading to protein misfolding and dysfunction in the different cellular compartments. Following deleterious REDOX state modifications, heat shock factor 1 (HSF1), the master regulator of heat shock response, is concurrently activated by its own change in conformation (5) and is released from a multichaperone complex, which preferentially interacts with abnormal protein. Activated HSF1 translocates into the nucleus and induces the expression of numerous chaperones or HSPs in addition to other genes participating to the stress response (94). Abnormal proteins can also accumulate in the ER, inducing the ER stress response. This response includes three different transcriptional regulators [X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) and activating factor 4 and 6 (ATF4 and -6)], which are activated and induce chaperone expression, in addition to mediators of other cellular mechanisms such as apoptosis (64).

Fig. 2.

Proteotoxic and cellular protective responses. Proteotoxic stress is defined by the presence of inappropriately folded proteins. This triggers two main cellular responses in an attempt to protect the cell against the deleterious effect of altered proteostasis. The heat shock (HS) response (left) is mainly regulated by HS factor 1 (HSF1), which becomes highly active by changes in conformation and release from multichaperone complex. HSF1 interacts with DNA binding sites and modifies the transcription of numerous genes including the chaperones, HS proteins (HSPs). The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response (also called unfolded protein response; right) is triggered by the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER compartment. This releases Ig heavy chain binding protein/HSPA5 from three complementary regulators, which are de-repressed and can activate a molecular cascade promoting transcription of ER chaperones genes (e.g., HSPA5 and HSP90B1) in addition to other functions not described. HSE, heat shock element; Grp78, glucose-regulated protein 78; IRE1, ER-resistant transmembrane kinase-endoribonuclease inositol-requiring enzyme 1; ATF6, activating factor 6; PERK, ER stress-activated eIF2α kinase; sXBP1, spliced X-box binding protein 1.

Proteostasis, REDOX State, and Cardiac Diseases

Cardiac dysfunction of various etiologies (i.e., ischemia, overload, and arrhythmia) exhibits global and, perhaps, localized changes in REDOX imbalance, either oxidative or reductive stress. Multiple deleterious consequences of such imbalance impact 1) the regulatory pathways based on ROS signaling; 2) the expression and/or function of proteins involved in the dynamic Ca2+ homeostasis; and 3) the myofibrillar proteins, among others (84, 91). In particular, REDOX-dependent posttranslational modifications (e.g., disulfide bond and carbonylation) alter the conformation of several myofibrillar proteins (Fig. 3), and this is likely to provoke functional changes of the sarcomeric contractile apparatus. Additionally, in the case of oxidative stress, specific subunits from the 19S proteasome become oxidized, leading to a significant reduction of the 26S proteasome activity (23). Likewise, elevated levels of ROS stimulate autophagy that, in turn, paradoxically lowers ROS by still poorly defined mechanisms [e.g., experimental work described in (107); and reviewed in (37)]. Shifts in the equilibrium between protein synthesis and degradation are guaranteed to alter the maintenance of cardiomyocyte homeostasis. Without a detailed understanding of the mechanisms involved (both deleterious and protective), therapeutic approaches that aim to reduce the harmful consequences on molecular defenses which can reverse cardiac dysfunction are likely to be stymied.

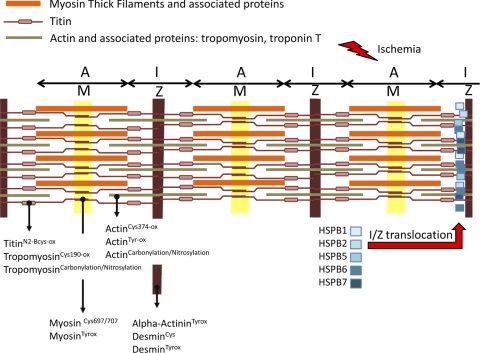

Fig. 3.

Stress-dependent modification of proteins in sarcomere. Schematic of the sarcomere unit is presented, showing thick and thin filaments. Reduction-oxidation modifications of proteins involved in sarcomeric structure are listed according to their position (17, 91). Mechanical and biochemical stresses can alter numerous sarcomeric proteins and possibly induce the translocation of several small HSPs in a defined region of the I-band (I) close to Z line (Z), as this was shown after ischemia-reperfusion (34). While not yet fully demonstrated, the expectation is that small HSPs can exert some protective effect on sarcomere structure. A, A-band; M, M line.

Myocardial ischemia.

Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury caused by a severe disruption in oxygen and nutrient supply dramatically impacts mitochondrial function and NOX activity. From data acquired by electron paramagnetic resonance microscopy (Table 3), the release of reactive oxygen-centered free radicals and burst of oxygen radical generation occur within moments of reperfusion. In isolated hearts, ischemic hearts after 10 min of ischemia and 10 s of oxygenated reperfusion led to a sixfold increased signal compared with that in control samples (115). Significant bursts of oxidative stress are initial targets for the antioxidant enzymatic (e.g., superoxide dismutase) and nonenzymatic pathways (e.g., glutathione pathways). In addition, the recruitment of regulatory defense systems against the deleterious effects of I/R occurs under the control of several redox-sensitive transcription factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), HSF1, NF-κB, and p45 NF-E2-related transcription factor (NRF2).

Extensive studies have established that the regulatory mechanisms governing HIF-1α pathway by ischemia are mediated at the levels of transcriptional, translational, and degradation (85). Discovered initially as the central regulatory mechanism for the upregulation of erythropoietin gene expression, HIF-1 constitutes an evolutionarily conserved oxygen-sensing mechanism responsible for scores of genes and physiological processes from angiogenesis to glycolysis to hypoxia. HIF-1 forms a heterodimeric complex of HIF-1α and HIF-1β subunits with properties of heterodimerization and DNA-binding activity but with dramatically distinct half-life of protein stability. Under normal conditions, HIF-1β remains constitutively expressed, whereas HIF-1α has a half-life of <1 min when sequential interactions with proline hydroxylases (PHDs) and von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor trigger rapid degradation by the proteasome (65).

In response to hypoxic stimulus, the activity of oxygen-sensor PHDs is significantly reduced and HIF-1α remains unhydroxylated, preventing interactions with von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor and promoting its stabilization. Therefore, the degradation of HIF-1α decreases because of the reduced activity of PHD due to conformational changes with low oxygen and higher ROS but also because of proteasome lower activity. During acute myocardial ischemia, HIF-1α activation is cardioprotective because of its regulatory targets of genes encoding Ca2+ handling and metabolic and angiogenic pathways. There are also interactions between HIF-1α and other factors such as HSF1 (6, 114). However, unregulated HIF-1α activation can be also deleterious, as recently shown by persistent stimulation of HIF1 activity, which causes cardiomyopathy (66).

In contrast to HIF-1, the expression of HSF1 is typically unchanged in response to an acute stress. HSF1 activation is regulated by posttranslational modifications, REDOX-dependent changes in conformation, and the release from inhibitory interactions involving HSPs (Fig. 2). Of interest, CAMKII δ B was recently suggested to link oxidative stress and HSF1 activation in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. With the increase of the level of S230 phosphorylation on HSF1, CAMKII δ B was shown to augment stress-inducible HSP70 expression (73). That activated HSF1 exerts beneficial roles during I/R was demonstrated using a transgenic mouse model expressing a constitutive active form of HSF1 (human β-actin-ΔHSF1) (113). Carboxyl-interacting protein of HSP70 (CHIP) normally contributes to HSF1 activation, but CHIP null mice exhibited a much more severe phenotype following experimental I/R (109). As expected, HSP expression correlated with HSF1 activity. In hearts of human β-actin-ΔHSF1 mice, the HSPs level was doubled, and beyond their protective role as chaperones, HSPs were shown to stimulate prosurvival pathway as exemplified by phosphorylation of Akt and to lower the prodeath pathway conducted by phosphorylated form of JNK. Several transgenic mouse models were generated to allow the overexpression of various HSPs, either directly regulated by HSF1 (HspB1, HspB5, and HspA1A) (18) or not (HspB6) (28, 29). Taken together, there is now compelling evidence that increased proteostasis mechanism(s) provide robust protection under I/R-induced REDOX imbalances.

Another important major regulator pathway for sensing oxidative stress cellular environment in the heart is NRF2 [reviewed in (69)]. NRF2 is a REDOX-sensitive transcription factor that is first negatively regulated by an interaction with Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 (Keap1), an E3 ligase responsible for its ubiquitination and degradation. Upon oxidative stress, Keap1 cysteine residues (Cys151) serve as stress sensors such that conformation changes of Keap1 prevent its interaction that promotes degradation of NRF2. In addition, NRF2 can be phosphorylated by ER stress mediator, ER stress-activated eIF2α kinase (PERK), contributing to its dissociation from Keap1 (19). Then NRF2 migrates into the nucleus to achieve DNA-binding activity of downstream targets. NRF2 protein contains critical cysteine that needs to be maintained in the reduced form, and this is achieved via REDOX reactions with the thiol-containing GSH and, more importantly, thioredoxin systems. NRF2 binds specific DNA sites described as antioxidant responsive element found in the regulatory regions of many genes such as NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase, gammaglutamylcysteine (GSH synthesis), glutathione-S-transferase, and heme oxygenase, which is also regulated by HIF-1 and HSF1. Several studies place NRF2 as a key transcription factor interacting with other REDOX regulators such redox effector factor-1, NF-κB (36), and NOX4, whose protective activity following I/R would be entirely mediated by NRF2 (15). NRF2 signaling mechanisms are being actively investigated since the range of downstream effectors could be therapeutically targeted for boosting antioxidative defenses.

Because ischemia generates ROS and protein oxidation, the molecular and cellular mechanisms for eliminating those abnormal proteins are critical for the survival of the affected cardiomyocytes in the ischemic heart. Proteasome activity is involved in eliminating oxidized actin (22, 75). Another protective mechanism, potentially under the proteasome control, is the degradation of phospho-c-jun implicated in triggering apoptosis (58). Ischemia also stimulates autophagy. Transgenic green fluorescent protein-microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain-3α (GFP-LC3) mice are an interesting model to monitor the autophagic activity since LC3 is specifically associated with autophagosomes. Thus the activation of autophagy after ischemia is revealed by the formation of GFP-LC3 aggregates, and this phenomenon is particularly visible in rescued cardiomyocytes located in the ischemic border zone region (48).

In this review, the focus has been restricted on the cardiomyocytes, but they also interact with their cellular environment which can provide various signals including changes in REDOX environment, such as communication between endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes [e.g., activation of neuregulin/erbB paracrine signaling in the intact heart subjected to oxidative stress following I/R injury (57)].

Cardiac hypertrophy.

Cardiac hypertrophy, or an increase in cardiomyocyte mass, has many triggers (e.g., pressure/volume overload) involving cellular responses to various (patho)physiological and pharmacological signals that are integrated through complex signaling pathways (1, 24, 42). During increased contractile demand, the heart undergoes hypertrophic response mediated through dynamic changes in the equilibrium between protein synthesis and degradation, allowing sarcomere addition. In fact, there are complex links between the distinct origins of cardiac hypertrophy and the different modes of protein degradation [e.g., inhibiting calpain activity disrupts cardiac hypertrophy (72)]. This also impacts the production of energy required to cope with such an elevated workload and is likely associated with a high risk of increased ROS generation by mitochondria. At the molecular level, it was shown that induced NOX4 activity following hypertrophic signaling (angiotensin II) contributed to the elevated production of ROS by mitochondria (3). Further discussion about the intervention of NOX4 in cardiac hypertrophy and other cardiovascular diseases can be found in recent reviews (4, 88).

Manifestations of both abnormal proteostasis and REDOX state imbalances were shown in a mouse model, recapitulating a human desmin-related cardiomyopathy due to the R120G mutation in the α-B-crystallin gene (HspB5, Table 2). Although R120G mice express the mutated HSPB5 along with the endogenous wild-type protein, by the age of 6 mo they show large aggregates occupying nearly the entire cardiomyocyte and severely disrupting the sarcomere organization (62). In addition, cardiomyocyte REDOX state is profoundly perturbed with an increased level of reduced GSH, leading to reductive stress. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) enzymatic activity is elevated in the mutant cardiomyocyte, and this can contribute to the observed imbalanced REDOX state since this enzyme plays a key role in the pathway producing NADPH, which is an essential cofactor of glutathione reductase in its catalysis of oxidized to reduced glutathione. Since significant cardiac hypertrophy with a high level of atrial and brain natriuretic factor expression is found in 6-mo-old R120G male mice, this suggested a causal link between G6PD activity and cardiac hypertrophy. This hypothesis was supported by the beneficial effect of introducing the R120G mutation in a G6PD-deficient genetic background (77). A second line of evidence is brought by a gain of function experiment overexpressing HspB1. Transgenic mice with a very high level of HSPB1 have a higher level of GSH and develop cardiac hypertrophy (110). How HSPB1 can lead to an increased GSH amount can be explained with previous work by Arrigo and colleagues (76), who had shown that HSPB1 is able to interact with G6PD and stimulate its activity. The link between R120G expression and reductive stress is likely to be complex, relying on multiple REDOX regulators. This is illustrated by experiments showing that the antioxidant factor, NRF2, is activated in R120G transgenic mice with the expected increased expression of NRF2 target genes [e.g., NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase and catalase] and a possible contribution to the REDOX imbalance in favor of higher antioxidants and reduced milieu (78).

Downstream the hypertrophic signaling pathways, a complex transcriptional regulation involving epigenetic modifications regulates the expression of hypertrophic genes [e.g., histone deacetylase (HDAC) (38, 51)]. This step further associates proteostasis and REDOX state as illustrated by the work performed by the laboratory of Sadoshima and colleagues (2). They demonstrated that HDAC4, a member of the class II HDAC, is regulated by REDOX reactive cysteines, Cys667 and Cys669 (2). DNAJb5, of which the level of expression is increased by thioredoxin 1, forms the REDOX-sensitive intermediate between thioredoxin1 and HDAC4 so that HDAC4 reactive cysteines remain reduced. This prevents HDAC4 export to the cytoplasm. SH-HDAC4, as it is located in the nucleus, ultimately maintains hypertrophic genes under a repressive-underacetylated chromatin.

Finally, as described in the context of I/R, cardiac hypertrophy is also associated with the cellular and ER stress responses mediated by the previously mentioned transcriptional factors (in particular HIF1-α, HSF1, and NRF2). Some level of interactions or cross talk between those different transcription factors is expected as their actions should converge to protect the cardiac cells. This was recently illustrated by the work performed with HSF1 mouse models. Zou and coworkers (114) demonstrated that HSF1 and HIF1-α are functionally connected to increase the expression of VEGF and stimulate beneficial angiogenesis after experimentally induced pressure overload.

Arrhythmia: atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is among the most common cardiac dysrhythmias. It has a lifelong risk for development in one of every four men and women over 40 years of age (59). Since AF imposes rapid and uncoordinated contraction on cardiomyocytes, the duration of the arrhythmia is an important factor inducing atrial remodeling (both electrical and structural) but also the activation of calpain, a sign of unbalanced proteostasis. In addition, AF leads to Ca2+ overload and this has been shown to be further associated with oxidative stress. In fact, accumulating evidence has supported the hypothesis of AF and oxidative stress as summarized by Huang and colleagues (43). This includes histological studies, which demonstrate the oxidative damage in case of AF, the presence of markers of oxidative stress (nearly quadrupled protein carbonylation; diminished level of reduced SH) (16) and some beneficial effects of antioxidant treatment.

As a link between proteostasis and REDOX state, the expression of HSPs, in particular HSP70 and HspB1 (Hsp25/27), is modified in chronically affected patients (46). In tachycardia-paced HL-1 atrial myocytes, an experimental model of AF, HspB1 and other members of the small HSP family were found to exert beneficial effects through distinct mechanisms. HspB1, -6, -7, and -8 were able to mitigate the reduced level of Ca2+ transients. HspB1, -6, and -7 intervene at the level of structural remodeling of actin stress fibers, and HspB8 specifically acts on RhoA GTPase, an upstream regulator of the cytoskeleton reorganization (50). In those studies, the REDOX state was not analyzed, so beyond HspB1, it remains to be determined whether the other small HSPs highly expressed in the heart can rescue an imbalanced REDOX state.

Therapeutic Agents: Friends and Foes in the Fight

Cardiovascular diseases represent one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in Western countries. Substantial insights on the basic mechanisms, etiologies, diagnostics, and therapeutics have fundamentally changed the management of cardiovascular diseases in recent decades. Therapeutic intervention interfering with REDOX state can have both positive and negative effects, as exemplified in the following selected examples.

Hype and hope in search for cardioprotective drugs.

As mentioned elsewhere (52), the preponderance of evidence of oxidative stress in most cardiac pathological processes has logically justified interventions using antioxidant drugs and dietary supplements (e.g., vitamins A, E, and C) for disease prevention. However, the positive results of antioxidants in experimental studies have not been confirmed in clinical studies that have even established increased adverse outcomes and toxicity of antioxidants (39). In the Medical Research Council/British Heart Foundation Heart Protection Study, for example, there were no significant differences between 20,536 individuals randomized to either supplementation with antioxidant vitamins or normal diet in the number of nonfatal myocardial infarction or coronary deaths [cited from (39)]. Likewise, among 58,730 Japanese individuals, there was no significant difference for men with vitamin C intake, but an inverse association for increased mortality from cardiovascular disease was found among Japanese women (55).

A substantial literature has documented the improvements of cardiac pathologies linked to oxidative stress by overexpression of HSP chaperones, providing proof of concept for beneficial targets of proteostasis boundaries [e.g., protective effect of HSP overexpression in transgenic mice (18)]. This concept awaits further translational studies from the bench to bedside and has yet to further prove the benefits of drugs with such capability of inducing chaperones.

Geranylgeranylacetone (GGA), an acyclic polyisprenoid and antiulcer drug developed in Japan, was first tested about 10 years ago in experimental studies on I/R in rats (68). A single-dose regimen of GGA doubled the levels of Hsp70 protein expression but did not change the expression of Hsp25/HspB1, Hsp60, and thioredoxin. A positive effect was observed after GGA treatment and was thus explained by the greater amount of Hsp70. This effect on Hsp70 expression could be due to the fact that GGA activates HSF1 (92). Sanbe and coworkers (83) have recently demonstrated that long-term GGA administration stimulates the expression of two small HSPs, i.e., HspB1 and HspB8, and can suppress the R120G-related cardiac disease in animal models. This shows that the same compound can induce diverse changes in protein expression (depending on the cellular or treatment conditions) and acts through multiple molecular mechanisms, including activation of various transcription factors since HSF1 does not regulate HspB8. To date, there are no clinical reports that have directly tested whether GGA has similar benefits for distinct forms of heart disease in humans.

Celastrol is a triterpenoid compound isolated from the plant family Celatraceae. This compound was shown to induce HSF1 activity as the classical heat shock (100). While best known for its anti-inflammatory properties in part through the inhibition of NF-κB pathway, celastrol exerts several salutary effects by abrogating the deleterious consequences of oxidative stress. Celastrol was successfully used to mitigate the consequences of the hypertension-induced inflammation and oxidative stress in vascular smooth muscle. Heme oxygenase was identified as a key component without determining the molecular link between the drug and this gene, which could be some REDOX-sensitive transcription factors, either NRF2 or HSF1 (54, 86). Interestingly, in the study by Yu et al. (106), they showed that cardiac hypertrophy was reduced in celastrol-treated hypertensive rats. This observation would require more investigation to determine whether celastrol acts directly on the cardiomyocyte.

Resveratrol, a small polyphenol (3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene) found in skin of red grapes, has generated considerable interest as a therapeutic agent in both experimental and clinical settings. Resveratrol is a potentially powerful antioxidant that can modify the expression of small HSPs in the heart (10), but its mechanisms of action remain to be better elucidated. Wu and Hsieh (104a) have recently reviewed resveratrol effects, mostly in the vascular compartment, but as already mentioned, evidence for direct impact on cardiomyocytes is accumulating. Resveratrol attenuates the cardiotoxicity of the antiretroviral drug, azidothymidine, by reducing the generation of mitochondrial ROS in primary human cardiomyocytes (31). A recent review summarizes the still-in-progress human clinical trials that test the efficacy of resveratrol effects for cardiovascular and other diseases (89).

Cardiotoxicity as a severe drawback for efficient cancer drugs.

Deleterious side effects remain another challenge for new drug discovery. Significant numbers of potential drug candidates are withdrawn from the market or are eliminated from further clinical studies because of cardiotoxicity. From a better understanding of the detailed mechanisms, there is hope that either such deleterious effects might be eliminated or more appropriate pharmacological treatment can be developed. Two common and efficient cancer drugs, which are implicated in REDOX state and proteostasis, best illustrate this conundrum.

Doxorubicin (Doxo), a member of the anthracycline derivative family, is among the most widely used and effective anti-cancer drugs. Unfortunately, Doxo treatment induces irreversible cardiotoxicity and dilated cardiomyopathy in a dose-dependent manner, and extensive studies have been undertaken to identify the causal mechanisms. In parallel with the drug's metabolism into an unstable semiquinone intermediate, Doxo administration both increases oxidative stress and induces chaperone-like HSP expression. ROS-dependent protein alterations might explain the cascade of adverse events causing cardiac dysfunction (dysregulation of Ca2+ handling) and cell death (mitochondria-dependent apoptosis) [review in (111)]. Although HSF1-dependent upregulation of HSPs contributed to the protective mechanisms for proteostasis against toxicity in cellular models [immortalized cardiac H9c2 (95)], experimental work with mouse models paradoxically revealed some opposite effects. Proteomic analysis showed an accumulation and aggregation of HSPB1 in Doxo-treated animals with heart failure. The loss of function of HSF1 reduces HSPB1 expression and consequently the HSPB1-dependent p53 induced apoptosis (97). The apparent contradiction between the results obtained by the same laboratory emphasizes the importance of considering the cell specificity of proteostasis and REDOX state. More detailed proteomics analysis confirms that Doxo treatment induces severe alterations in the mitochondria, along with antioxidant defense pathways (90). In addition, Doxo seems to activate the proteolytic machinery, in particular UPS, in such a way that critical cardiac transcription factors and survival factors are overtly degraded [review in (79)]. Based on experiments using animal models, the stimulating overexpression of the cardiac HSP20 (small HSPB6) could be beneficial (29).

Bortezomib (Velcade), an inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, is commonly used for treatment of multiple myeloma and other refractory lymphomas. The incidence of cardiotoxicity, including heart failure, was 15% among a group of 699 treated patients with multiple myeloma (81). Some severe, reversible cardiac failure after bortezomib treatment, combined with chemotherapy, has been reported in a case of non-small cell lung cancer (105). The mechanism of action of such a drug depends on the selective degradation of proapoptotic factors in relation to the programmed cell death in neoplastic compared with normal cells. How those drugs induce cardiotoxicity remain enigmatic but likely depend on the inhibition of the proteasome itself, in association with some age-dependent cardiac susceptibility. Recent investigations have implicated the mitochondrion, a very sensitive organelle, in the toxicity mechanism. It is tempting to speculate that mitochondria dysfunction causes oxidative stress and further alterations of the UPS, a central mechanism for removing damaged proteins to enhancing proteostasis.

Perspectives

As cited in this paper, numerous reviews have recently covered some aspects of the present topic: proteostasis and REDOX state (84, 91, 101–103). There is a considerable urgency to establish new therapies and preventative strategies to circumscribe cardiovascular dysfunction associated with protein alterations and REDOX imbalance. Additional evidence for such a need includes the demonstration of the burgeoning increases in metabolic diseases such as diabetes, altering REDOX balance, and the aging-dependent mechanisms that further reduce proteostasis capability.

In the face of this situation, intense efforts need to be devoted to improve the clinical applications of the combined uses of radiotracer and REDOX-sensitive dyes, which could herald new diagnostics with greater sensitivity and specificity of REDOX state. Furthermore, a better understanding of the complex regulation of cellular REDOX balance could facilitate the development of newer antioxidants aimed at specific cellular targets such as organelles, vessels, and cardiomyocytes (20). Certainly, previous unsuccessful clinical trials should not prevent efforts to design and deploy new innovative drug strategy testing after an adequate identification of the targets and a more efficient screening for highly specific targets in the era of personalized medicine.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Award 2-R01-HL-063834-06 (to I. J. Benjamin); 2009 National Institutes of Health Director's Pioneer Award 1DP1OD006438-02; Veterans Administration Merit Review Award (to I. J. Benjamin); NHLBI Grant 5-R01-HL-074370-03 (to I. J. Benjamin); and Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence (to I. J. Benjamin).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Jamila Roehrig provided excellent editorial assistance during preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abel ED, Doenst T. Mitochondrial adaptations to physiological vs. pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 90: 234–242, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ago T, Liu T, Zhai P, Chen W, Li H, Molkentin JD, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. A redox-dependent pathway for regulating class II HDACs and cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 133: 978–993, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ago T, Kuroda J, Pain J, Fu C, Li H, Sadoshima J. Upregulation of Nox4 by hypertrophic stimuli promotes apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 106: 1253–1264, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ago T, Kuroda J, Kamouchi M, Sadoshima J, Kitazono T. Pathophysiological roles of NADPH oxidase/nox family proteins in the vascular system. Circ J 75: 1791–1800, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahn SG, Thiele DJ. Redox regulation of mammalian heat shock factor 1 is essential for Hsp gene activation and protection from stress. Genes Dev 17: 516–528, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ali YO, McCormack R, Darr A, Zhai RG. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase is a stress response protein regulated by the heat shock factor/hypoxia-inducible factor 1α pathway. J Biol Chem 286: 19089–19099, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aon MA, Cortassa S, O'Rourke B. Redox-optimized ROS balance: a unifying hypothesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 865–877, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benjamin IJ, McMillan DR. Stress (heat shock) proteins: molecular chaperones in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res 83: 117–132, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisén J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324: 98–102, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bezstarosti K, Das S, Lamers JM, Das DK. Differential proteomic profiling to study the mechanism of cardiac pharmacological preconditioning by resveratrol. J Cell Mol Med 10: 896–907, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11. Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 297: 842–857, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boateng SY, Belin RJ, Geenen DL, Margulies KB, Martin JL, Hoshijima M, de Tombe PP, Russell B. Cardiac dysfunction and heart failure are associated with abnormalities in the subcellular distribution and amounts of oligomeric muscle LIM protein. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H259–H269, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boateng SY, Goldspink PH. Assembly and maintenance of the sarcomere night and day. Cardiovasc Res 77: 667–675, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brady JP, Garland DL, Green DE, Tamm ER, Giblin FJ, Wawrousek EF. AlphaB-crystallin in lens development and muscle integrity: a gene knockout approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 2924–2934, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brewer AC, Murray TV, Arno M, Zhang M, Anilkumar NP, Mann GE, Shah AM. Nox4 regulates Nrf2 and glutathione redox in cardiomyocytes in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 205–215, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bukowska A, Schild L, Keilhoff G, Hirte D, Neumann M, Gardemann A, Neumann KH, Rohl FW, Huth C, Goette A, Lendeckel U. Mitochondrial dysfunction and redox signaling in atrial tachyarrhythmia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 558–574, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Canton M, Menazza S, Sheeran FL, Polverino de Laureto P, DiLisa F, Pepe S. Oxidation of myofibrillar proteins in human heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 300–309, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Christians ES, Benjamin IJ. The stress or heat shock (HS) response: insights from transgenic mouse models. Methods 35: 170–175, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol 23: 7198–7209, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Rosa S, Cirillo P, Paglia A, Sasso L, DiPalma V, Chiariello M. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease: does the actual knowledge justify a clinical approach? Curr Vasc Pharmacol 8: 259–275, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delogu G, Signore M, Mechelli A, Famularo G. Heat shock proteins and their role in heart injury. Curr Opin Crit Care 8: 411–416, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Divald A, Powell SR. Proteasome mediates removal of proteins oxidized during myocardial ischemia. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 156–164, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Divald A, Kivity S, Wang P, Hochhauser E, Roberts B, Teichberg S, Gomes AV, Powell SR. Myocardial ischemic preconditioning preserves postischemic function of the 26S proteasome through diminished oxidative damage to 19S regulatory particle subunits. Circ Res 106: 1829–1838, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diviani D, Dodge-Kafka KL, Li J, Kapiloff MS. A-kinase anchoring proteins: scaffolding proteins in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1742–H1753, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dorn GW, 2nd, Scorrano L. Two close, too close: sarcoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial crosstalk and cardiomyocyte fate. Circ Res 107: 689–699, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dreiza CM, Komalavilas P, Furnish EJ, Flynn CR, Sheller MR, Smoke CC, Lopes LB, Brophy CM. The small heat shock protein, HSPB6, in muscle function and disease. Cell Stress Chaperones 15: 1–11, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edwards HV, Cameron RT, Baillie GS. The emerging role of HSP20 as a multifunctional protective agent. Cell Signal 23: 1447–1454, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fan GC, Ren X, Qian J, Yuan Q, Nicolaou P, Wang Y, Jones WK, Chu G, Kranias EG. Novel cardioprotective role of a small heat-shock protein, Hsp20, against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 111: 1792–1799, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fan GC, Zhou X, Wang X, Song G, Qian J, Nicolaou P, Chen G, Ren X, Kranias EG. Heat shock protein 20 interacting with phosphorylated Akt reduces doxorubicin-triggered oxidative stress and cardiotoxicity. Circ Res 103: 1270–1279, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Forkink M, Smeitink JA, Brock R, Willems PH, Koopman WJ. Detection and manipulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 1034–1044, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gao RY, Mukhopadhyay P, Mohanraj R, Wang H, Horvath B, Yin S, Pacher P. Resveratrol attenuates azidothymidine-induced cardiotoxicity by decreasing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in human cardiomyocytes. Mol Med Report 4: 151–155, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gidalevitz T, Prahlad V, Morimoto RI. The stress of protein misfolding: from single cells to multicellular organisms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3, pii: a009704, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Godoy JR, Funke M, Ackermann W, Haunhorst P, Oesteritz S, Capani F, Elsasser HP, Lillig CH. Redox atlas of the mouse. Immunohistochemical detection of glutaredoxin-, peroxiredoxin-, and thioredoxin-family proteins in various tissues of the laboratory mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta 1810: 2–92, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Golenhofen N, Perng MD, Quinlan RA, Drenckhahn D. Comparison of the small heat shock proteins alphaB-crystallin, MKBP, HSP25, HSP20, and cvHSP in heart and skeletal muscle. Histochem Cell Biol 122: 415–425, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Groenendyk J, Sreenivasaiah PK, Kimdo H, Agellon LB, Michalak M. Biology of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ Res 107: 1185–1197, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gurusamy N, Malik G, Gorbunov NV, Das DK. Redox activation of Ref-1 potentiates cell survival following myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med 43: 397–407, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gurusamy N, Das DK. Autophagy, redox signaling, and ventricular remodeling. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 1975–1988, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet 10: 32–42, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haffey TA. How to avoid a heart attack: putting it all together. J Am Osteopath Assoc 110: 397–400, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475: 324–332, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hedhli N, Pelat M, Depre C. Protein turnover in cardiac cell growth and survival. Cardiovasc Res 68: 186–196, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 589–600, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang CX, Liu Y, Xia WF, Tang YH, Huang H. Oxidative stress: a possible pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Med Hypotheses 72: 466–467, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang L, Min JN, Masters S, Mivechi NF, Moskophidis D. Insights into function and regulation of small heat shock protein 25 (HSPB1) in a mouse model with targeted gene disruption. Genesis 45: 487–501, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jones DP, Go YM. Redox compartmentalization and cellular stress. Diabetes Obes Metab 12, Suppl 2: 116–125, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kampinga HH, Henning RH, van Gelder IC, Brundel BJ. Beat shock proteins and atrial fibrillation. Cell Stress Chaperones 12: 97–100, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kampinga HH, Hageman J, Vos MJ, Kubota H, Tanguay RM, Bruford EA, Cheetham ME, Chen B, Hightower LE. Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins. Cell Stress Chaperones 14: 105–111, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kanamori H, Takemura G, Goto K, Maruyama R, Ono K, Nagao K, Tsujimoto A, Ogino A, Takeyama T, Kawaguchi T, Watanabe T, Kawasaki M, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H, Seishima M, Minatoguchi S. Autophagy limits acute myocardial infarction induced by permanent coronary artery occlusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H2261–H2271, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kavazis AN, McClung JM, Hood DA, Powers SK. Exercise induces a cardiac mitochondrial phenotype that resists apoptotic stimuli. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H928–H935, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ke L, Meijering RA, Hoogstra-Berends F, Mackovicova K, Vos MJ, Van Gelder IC, Henning RH, Kampinga HH, Brundel BJ. HSPB1, HSPB6, HSPB7 and HSPB8 protect against RhoA GTPase-induced remodeling in tachypaced atrial myocytes. PLoS One 6: e20395, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kee HJ, Kook H. Roles and targets of class I and IIa histone deacetylases in cardiac hypertrophy. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011: 928326, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kelly FJ. Use of antioxidants in the prevention and treatment of disease. J Int Fed Clin Chem 10: 21–23, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Klein I, Samarel AM, Welikson R, Hong C. Heterotopic cardiac transplantation decreases the capacity for rat myocardial protein synthesis. Circ Res 68: 1100–1107, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Koizumi S, Gong P, Suzuki K, Murata M. Cadmium-responsive element of the human heme oxygenase-1 gene mediates heat shock factor 1-dependent transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem 282: 8715–8723, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kubota Y, Iso H, Date C, Kikuchi S, Watanabe Y, Wada Y, Inaba Y, Tamakoshi A. Dietary intakes of antioxidant vitamins and mortality from cardiovascular disease: the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study (JACC) study. Stroke 42: 1665–1672, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kumarapeli AR, Su H, Huang W, Tang M, Zheng H, Horak KM, Li M, Wang X. Alpha B-crystallin suppresses pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 103: 1473–1482, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kuramochi Y, Cote GM, Guo X, Lebrasseur NK, Cui L, Liao R, Sawyer DB. Cardiac endothelial cells regulate reactive oxygen species-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through neuregulin-1beta/erbB4 signaling. J Biol Chem 279: 51141–51147, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li HH, Du J, Fan YN, Zhang ML, Liu DP, Li L, Lockyer P, Kang EY, Patterson C, Willis MS. The ubiquitin ligase MuRF1 protects against cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by its proteasome-dependent degradation of phospho-c-Jun. Am J Pathol 178: 1043–1058, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 110: 1042–1046, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lukyanenko V, Chikando A, Lederer WJ. Mitochondria in cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 1957–1971, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Margittai E, Sitia R. Oxidative protein folding in the secretory pathway and redox signaling across compartments and cells. Traffic 12: 1–8, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McLendon PM, Robbins J. Desmin-related cardiomyopathy: an unfolding story. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1220–H1228, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Meyer AJ, Dick TP. Fluorescent protein-based redox probes. Antioxid Redox Signal 13: 621–650, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Minamino T, Kitakaze M. ER stress in cardiovascular disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 1105–1110, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Miyata T, Takizawa S, van Ypersele de Strihou Hypoxia C. 1. Intracellular sensors for oxygen and oxidative stress: novel therapeutic targets. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C226–C231, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moslehi J, Minamishima YA, Shi J, Neuberg D, Charytan DM, Padera RF, Signoretti S, Liao R, Kaelin WG., Jr Loss of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase activity in cardiomyocytes phenocopies ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 122: 1004–1016, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nag AC. Study of non-muscle cells of the adult mammalian heart: a fine structural analysis and distribution. Cytobios 28: 41–61, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ooie T, Takahashi N, Saikawa T, Nawata T, Arikawa M, Yamanaka K, Hara M, Shimada T, Sakata T. Single oral dose of geranylgeranylacetone induces heat-shock protein 72 and renders protection against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat heart. Circulation 104: 1837–1843, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Osburn WO, Kensler TW. Nrf2 signaling: an adaptive response pathway for protection against environmental toxic insults. Mutat Res 659: 31–39, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Padrao AI, Ferreira RM, Vitorino R, Alves RM, Neuparth MJ, Duarte JA, Amado F. OXPHOS susceptibility to oxidative modifications: the role of heart mitochondrial subcellular location. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807: 1106–1113, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Papageorgopoulos C, Caldwell K, Schweingrubber H, Neese RA, Shackleton CH, Hellerstein M. Measuring synthesis rates of muscle creatine kinase and myosin with stable isotopes and mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem 309: 1–10, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Patterson C, Portbury AL, Schisler JC, Willis MS. Tear me down: role of calpain in the development of cardiac ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Res 109: 453–462, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Peng W, Zhang Y, Zheng M, Cheng H, Zhu W, Cao CM, Xiao RP. Cardioprotection by CaMKII-deltaB is mediated by phosphorylation of heat shock factor 1 and subsequent expression of inducible heat shock protein 70. Circ Res 106: 102–110, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Portbury AL, Willis MS, Patterson C. Tearin' up my heart: proteolysis in the cardiac sarcomere. J Biol Chem 286: 9929–9934, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Powell SR. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiac physiology and pathology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1–H19, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Preville X, Salvemini F, Giraud S, Chaufour S, Paul C, Stepien G, Ursini MV, Arrigo AP. Mammalian small stress proteins protect against oxidative stress through their ability to increase glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity and by maintaining optimal cellular detoxifying machinery. Exp Cell Res 247: 61–78, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rajasekaran NS, Connell P, Christians ES, Yan LJ, Taylor RP, Orosz A, Zhang XQ, Stevenson TJ, Peshock RM, Leopold JA, Barry WH, Loscalzo J, Odelberg SJ, Benjamin IJ. Human alpha B-crystallin mutation causes oxido-reductive stress and protein aggregation cardiomyopathy in mice. Cell 130: 427–439, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rajasekaran NS, Varadharaj S, Khanderao GD, Davidson CJ, Kannan S, Firpo MA, Zweier JL, Benjamin IJ. Sustained activation of nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2/antioxidant response element signaling promotes reductive stress in the human mutant protein aggregation cardiomyopathy in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 957–971, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ranek MJ, Wang X. Activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Curr Hypertens Rep 11: 389–395, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Razeghi P, Sharma S, Ying J, Li YP, Stepkowski S, Reid MB, Taegtmeyer H. Atrophic remodeling of the heart in vivo simultaneously activates pathways of protein synthesis and degradation. Circulation 108: 2536–2541, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Irwin D, Stadtmauer EA, Facon T, Harousseau JL, Ben-Yehuda D, Lonial S, Goldschmidt H, Reece D, San-Miguel JF, Bladé J, Boccadoro M, Cavenagh J, Dalton WS, Boral AL, Esseltine DL, Porter JB, Schenkein D, Anderson KC. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 352: 2487–2498, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Riva A, Tandler B, Loffredo F, Vazquez E, Hoppel C. Structural differences in two biochemically defined populations of cardiac mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H868–H872, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sanbe A, Daicho T, Mizutani R, Endo T, Miyauchi N, Yamauchi J, Tanonaka K, Glabe C, Tanoue A. Protective effect of geranylgeranylacetone via enhancement of HSPB8 induction in desmin-related cardiomyopathy. PLoS One 4: e5351, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Santos CX, Anilkumar N, Zhang M, Brewer AC, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac myocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 50: 777–793, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Semenza GL. Hydroxylation of HIF-1: oxygen sensing at the molecular level. Physiology 19: 176–182, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Seo WY, Goh AR, Ju SM, Song HY, Kwon DJ, Jun JG, Kim BC, Choi SY, Park J. Celastrol induces expression of heme oxygenase-1 through ROS/Nrf2/ARE signaling in the HaCaT cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 407: 535–540, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Shirley RL, Palting F, Easley JF, Carpenter JW, Koger M. Water, phosphorus, calcium, ash and protein in heart, liver and muscel of Hereford, Brehman and Hereford-Brehman cross-bred cattle. J Anim Sci 22: 393–395, 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sirker A, Zhang M, Shah AM. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular disease: insights from in vivo models and clinical studies. Basic Res Cardiol 106: 735–747, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Smoliga JM, Baur JA, Hausenblas HA. Resveratrol and health—a comprehensive review of human clinical trials. Mol Nutr Food Res 55: 1129–1141 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Stěrba M, Popelová O, Lenčo J, Fučíková A, Brčáková E, Mazurová Y, Jirkovský E, Simůnek T, Adamcová M, Mičuda S, Stulík J, Geršl V. Proteomic insights into chronic anthracycline cardiotoxicity. J Mol Cell Cardiol 50: 849–862, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sumandea MP, Steinberg SF. Redox signaling and cardiac sarcomeres. J Biol Chem 286: 9921–9927, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Tanaka K, Tsutsumi S, Arai Y, Hoshino T, Suzuki K, Takaki E, Ito T, Takeuchi K, Nakai A, Mizushima T. Genetic evidence for a protective role of heat shock factor 1 against irritant-induced gastric lesions. Mol Pharmacol 71: 985–993, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Taylor RP, Benjamin IJ. Small heat shock proteins: a new classification scheme in mammals. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 433–444, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Trinklein ND, Murray JI, Hartman SJ, Botstein D, Myers RM. The role of heat shock transcription factor 1 in the genome-wide regulation of the mammalian heat shock response. Mol Biol Cell 15: 1254–1261, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Turakhia S, Venkatakrishnan CD, Dunsmore K, Wong H, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL, Ilangovan G. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: direct correlation of cardiac fibroblast and H9c2 cell survival and aconitase activity with heat shock protein 27. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3111–H3121, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Understanding protein non-folding. Biochim Biophys Acta 1804: 1231–1264, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Vedam K, Nishijima Y, Druhan LJ, Khan M, Moldovan NI, Zweier JL, Ilangovan G. Role of heat shock factor-1 activation in the doxorubicin-induced heart failure in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1832–H1841, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Vliegen HW, van der Laarse A, Cornelisse CJ, Eulderink F. Myocardial changes in pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy. A study on tissue composition, polyploidization and multinucleation. Eur Heart J 12: 488–494, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Vos MJ, Kanon B, Kampinga HH. HSPB7 is a SC35 speckle resident small heat shock protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 1343–1353, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Westerheide SD, Bosman JD, Mbadugha BN, Kawahara TL, Matsumoto G, Kim S, Gu W, Devlin JP, Silverman RB, Morimoto RI. Celastrols as inducers of the heat shock response and cytoprotection. J Biol Chem 279: 56053–56060, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Willis MS, Schisler JC, Portbury AL, Patterson C. Build it up-Tear it down: protein quality control in the cardiac sarcomere. Cardiovasc Res 81: 439–448, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]